By Thomas P. McKenna

One of the most interesting characters arising out of the Spanish-American War was Lt. Andrew Summers Rowan, who was selected by President William McKinley to carry a secret message to the Cuban general Calixto Garcia. After his deed, his name and fame spread far and wide. When America went to war with Spain in the spring of 1898, the War Department needed information on the Spanish forces in Cuba, and on the willingness and ability of the Cuban insurgents to cooperate with an American invasion. That required a secret agent infiltrating Spanish-occupied Cuba, finding the insurgent General Garcia, exchanging information with him, and returning from behind enemy lines with information on both the insurgents and the Spanish. The man chosen for this important and dangerous mission was Lieutenant Rowan, an infantry officer working in the fledgling U.S. Army intelligence office in Washington, D.C. Rowan was a logical choice because he spoke Spanish, had been to Cuba, and had even coauthored a descriptive and historical book about the island.

On April 9 Lieutenant Rowan sailed from New York on a civilian ship bound for Kingston, Jamaica, where he made a clandestine rendezvous with Cuban exiles who could lead him to Garcia. He was then taken on a wild night ride through the Jamaican jungle to the northern coast. At the beach a Cuban sailor carried Rowan on his shoulders out through the surf to a small, open fishing boat. They set sail across a hundred miles of open water to Cuba, all the while evading Spanish navy patrols, one of which came within hailing distance. With everyone except the helmsman hiding below the gunwale they were able to pass for a fishing boat. When Rowan stepped ashore early on the second day, he was the first American officer to land in Cuba after the declaration of war. He was traveling in civilian clothes and certainly would have been shot as a spy if caught by the Spaniards.

Attacked by ‘Deserters’ in the Night

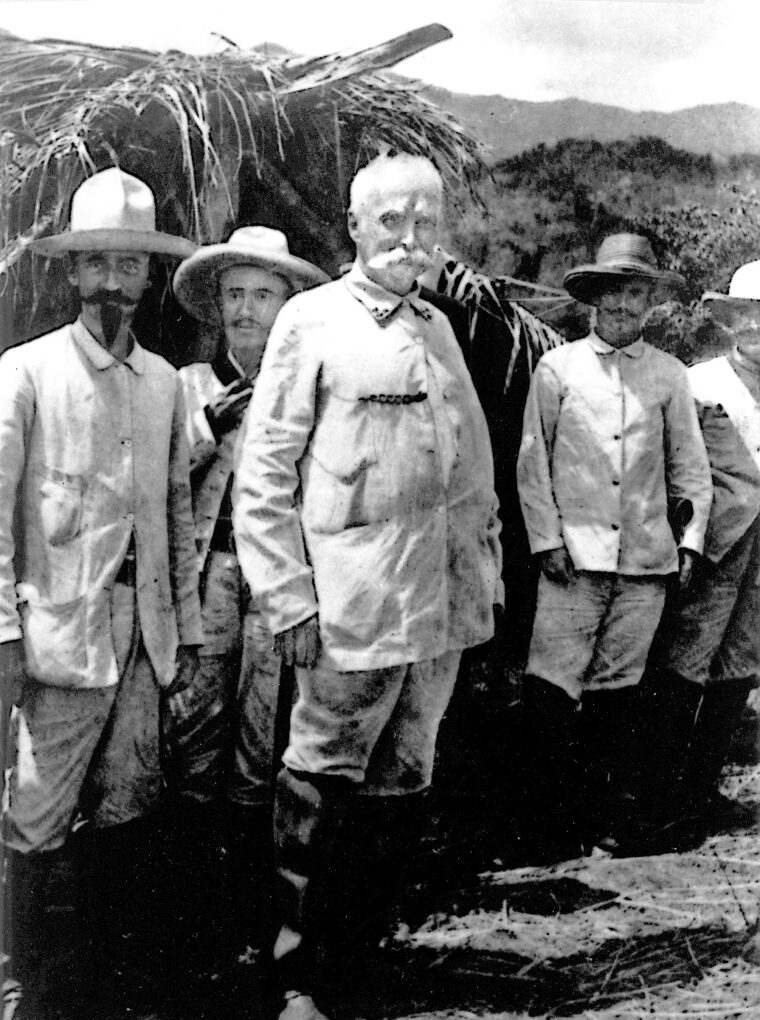

Their landing area was a tangled mangrove swamp and definitely not a suitable place for an invading army to land. They used machetes to hack through it, then through cactus and thorn, until they could climb into the Sierra Maestra mountains. A Spanish patrol forced them to hide beside the road but an even closer call came that night. Two Spanish “deserters” in an insurgents’ camp aroused Rowan’s suspicions and one tried to stab him while he slept. Both were shot dead by the Cubans. After several more days, now on horseback, Rowan reached Gen. Calixto Garcia’s mountain camp at Bayamo on May 1.

Garcia gave Rowan a glass of rum, breakfast, and a promise of whatever cooperation the guerrillas could provide to the Americans. Lieutenant Rowan also collected information on the Spanish troop dispositions and defenses. General Garcia selected three of his own officers to return with Rowan to provide additional information and to accompany the invading American forces as liaison officers.

Broiling, Bailing, Bailing, Broiling…

Rowan took a different route home. Accompanied by five Cubans he continued north through the mountains and jungle, sneaking past Spanish forts. After five days the six men reached the coast and hacked their way through mangrove swamps to the ocean and a boat so small it could carry only five. They made sails from gunnysacks and collected food from the jungle for the two hundred-mile voyage north across the Caribbean to Nassau. Rowan described how they sailed, “passing under the guns of a small Spanish fort,” and recalled the trip as, “broiling, bailing, bailing, and broiling.” They again evaded Spanish navy patrols and reached the Bahamas several days later.

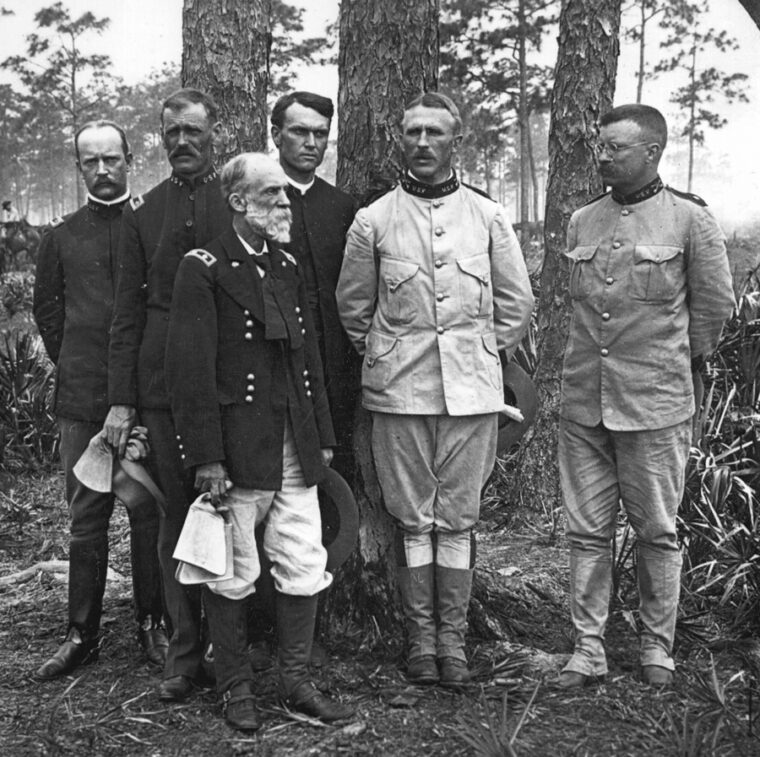

Thirteen days after leaving Garcia, Lieutenant Rowan arrived in Key West. From there he traveled by train to Washington, where he reported to Secretary of War Russell A. Alger and the commanding General of the Army, Gen. Nelson A. Miles. The next day Rowan and General Miles attended President McKinley’s cabinet meeting where Rowan briefed the President and was congratulated by him. His reward for completing this mission was appointment as a lieutenant colonel of volunteers in one of the new volunteer regiments formed to augment the regular army.

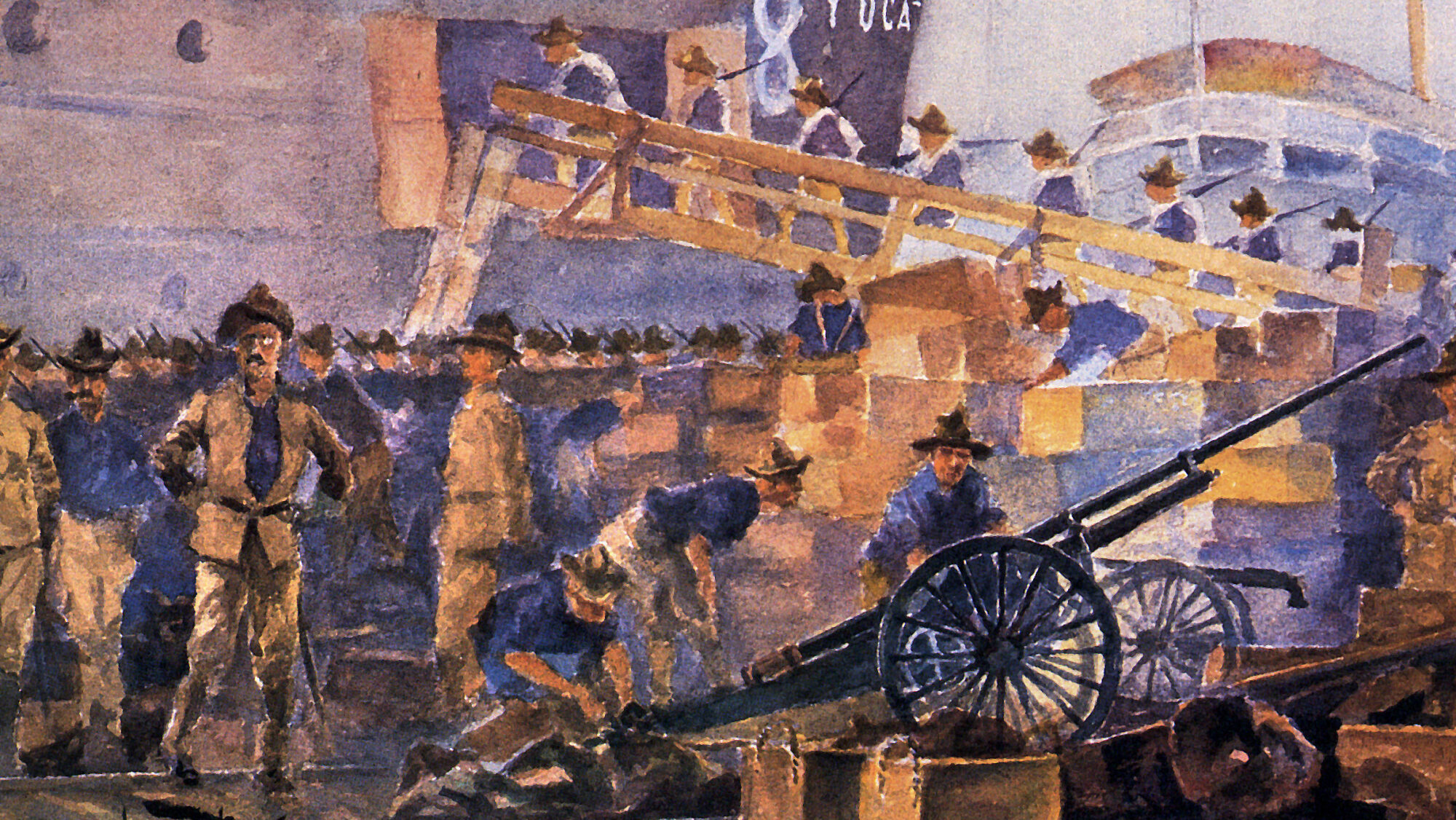

As a result of Rowan’s mission, Garcia advised the Americans to land at Daiquiri, made a diversionary attack there to facilitate their landing without Spanish opposition, and helped win the battles of El Caney and Santiago.

Half a Million Men Volunteered; by Fall 263,609 Remained

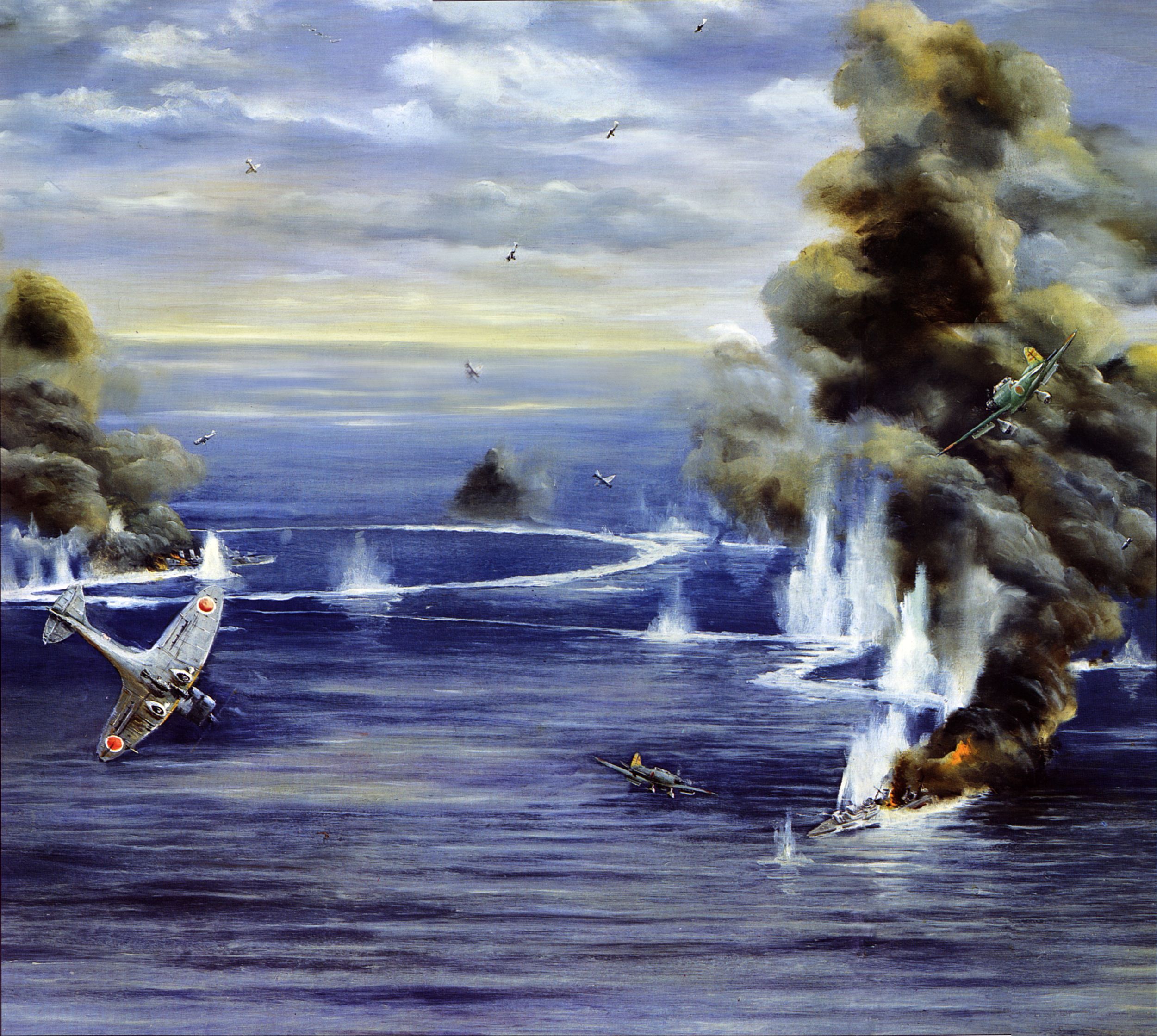

But this is getting ahead of the story. The invasion force was not ready when Rowan returned. In fact, it took many months to assemble, equip, and train the mostly volunteer army. In early 1898, the regular army was only 25,000 strong and most of it was scattered across small, isolated posts in the West. The stagnation of promotions in such a small army was illustrated by Rowan, who had graduated from West Point in 1881 and was still a lieutenant after 17 years of service. There had been no mobilization or large-scale maneuvers and no amphibious training with the navy since the Civil War ended 33 years before. Consequently the mobilization, and the supply and movements by rail and ship, were chaotic and disorganized. Half a million men volunteered and by August there were 263,609 soldiers in the army. Training and equipping them meant months of delay before the invasion fleet left Tampa in mid-June. By then Adm. George Dewey had already destroyed the Spanish Pacific fleet in a major victory at Manila Bay and most of the attention had turned to Cuba again.

For his mission to Garcia, Rowan was honorably mentioned in orders for distinguished service in Cuba “securing most valuable information under perilous circumstances.” He was recommended for brevet colonel of U.S. Volunteers, an honorary title, for gallantry at Guanica, Puerto Rico, in July 1898, where he led his volunteer regiment in battle.

“In All This Cuban Business One Man Stands Out on the Horizon of My Memory…”

When the volunteer army was disbanded after the war, the regular army officers reverted to their permanent ranks and Lieutenant Colonel Rowan again became Lieutenant Rowan. However, he was soon promoted to captain and sent to fight in the Philippines. In 1899 the Filipinos resumed an insurgency that had started against Spain and it took the U.S. Army three years of bitter fighting to put it down.

Rowan was wounded and received a citation for his action in the Philippines, but it was his mission to General Garcia that made him a part of American history. His personal account of his adventure, “My Ride Across Cuba,” was published in McClure’s magazine in August 1898, and two other personal accounts were published in the 1920s.

Rowan was not a popular hero of the same stature as Admiral Dewey at Manila Bay or Theodore Roosevelt at San Juan Hill. But in 1899 his fame was given a big boost by Elbert Hubbard, an essayist and publisher of the magazine Philistine, who wrote a piece about the value of personal initiative and attention to duty entitled, “A Message to Garcia.” Using Rowan as an example, he wrote:

“In all this Cuban business there is one man stands out on the horizon of my memory.… When war broke out between Spain and the United States, it was very necessary to communicate quickly with the leader of the Insurgents. Garcia was somewhere in the mountain vastness of Cuba—no one knew where. No mail or telegraph message could reach him. The President must secure his co-operation, and quickly. What to do!

“Rowan was sent for and given a letter to be delivered to Garcia. How [he] … took the letter[,] sealed it up in an oilskin pouch, strapped it over his heart, in four days landed by night off the coast of Cuba from an open boat, disappeared into the jungle, and in three weeks came out on the other side of the Island, having traversed a hostile country on foot, and delivered his letter to Garcia—are things I have no special desire now to tell in detail. The point that I wish to make is this: McKinley gave Rowan a letter to be delivered to Garcia; Rowan took the letter and did not ask, ‘Where is he at?’

“By the Eternal! There is a man whose form should be cast in deathless bronze and the statue placed in every college of the land. It is not book-learning young men need, not instruction about this and that but a stiffening of the vertebrae which will cause them to be loyal to a trust, to act promptly, concentrate their energies: do the thing—‘Carry a message to Garcia.’ Civilization is one thing, an anxious search for just such individuals. Anything such a man asks, shall be granted. He is wanted in every city, town and village—in every office, shop, store and factory. The world cries out for such; he is needed and needed badly—the man who can ‘Carry a Message to Garcia.’”

A Copy was Given to Every American, Russian, and Japanese Soldier

Hubbard received requests for dozens, then hundreds, of extra copies of Philistine until it was sold out. When the American News Company ordered a thousand he asked which article was so in demand and learned it was the one about Rowan. Next a telegram from the New York Central Railroad asked him to “Give price on one hundred thousand Rowan articles in pamphlet form … also how soon can ship?” Such a large printing was beyond the capabilities of Hubbard’s facility so he gave the railroad permission to reprint it themselves. It issued the essay in booklet form in two or three editions of half a million copies each.

Hubbard made some amazing claims about his essay. He said it was reprinted in over two hundred magazines and newspapers and was translated into all written languages. When Prince Hilakoff, director of the Russian railways, visited the New York Central Railroad he was so impressed by the message of initiative and devotion to duty, or perhaps by the number of copies distributed by the American railroad, that he gave a copy in Russian to all his employees. During the Russo-Japanese war in 1904-05 a copy was given to every Russian soldier who went to the front. After taking it from Russian prisoners, the Japanese concluded it must be a good thing, translated it, and gave copies to every Japanese soldier and government employee.

Hubbard died on the Lusitania when it was torpedoed in 1915 but Rowan claimed his essay was used for recruiting by the U.S. Army and Navy in World War I. Henceforth he would be remembered as “The man who carried the message to Garcia.”

A Reputation Marred by Vice

Unfortunately, some heroes have character flaws that detract from their famous achievements and Andrew S. Rowan was one of them. He had a drinking problem. The next decades were a series of bouquets and brickbats for him. While fighting Filipino insurgents in 1900 Captain Rowan was charged by one of his second lieutenants with using vulgar and abusive language toward other officers, to their faces, behind their backs, and in front of their troops. The charges did not result in a court martial but still remain in Rowan’s official record. These cannot be dismissed as the accusations of just one disgruntled subordinate because Rowan’s records contain other substantiating reports of similar conduct.

In 1900 Representative David Johnson of West Virginia, Rowan’s home state, asked the adjutant general to recommend Rowan for the Medal of Honor for his mission to Garcia. The War Department response was that he did not meet the criteria, especially the one requiring that the deeds occur “in action.”

In 1903 Captain Rowan was in charge of the ROTC program at Kansas State Agricultural College in Manhattan, Kansas. The president of the college wrote to the War Department asking that Rowan be replaced because he had been drunk “for four or five days during the recent flooding,” and was “not fit to appear in company during commencement.” He noted that “Kansas is a prohibition state.” Rowan was recalled and sent back to his regiment, the 19th Infantry.

Although Rowan’s performance ratings had been excellent until then, it became obvious he not only could not walk on water but that he put too little of it in his bourbon. In subsequent years he received official letters that required him to explain why he had not been present for certain troop formations or training. In 1904 his regimental commander reported that he took little interest in his military duties and “his habit of criticism of his superiors is such as to be a menace to discipline.” The commanding general of the army sent one of Rowan’s annual efficiency reports back to his commander with instructions to take corrective action on Captain Rowan’s “intemperate habits.” Rowan’s request for assignment to the prestigious War College in Washington was not approved. Twice he was compelled to officially apologize to officers for speaking to and about them in an outrageous manner. He was reprimanded for being under the influence of liquor in 1906 before leaving for field service, and for drinking to excess in 1909.

Honor Rises Above Shame

His mission to Garcia and his wartime service apparently outweighed his drinking problems enough to allow his promotion to major, but no higher. In 1909, after 32 years’ service, Major Rowan was retired at his own request. He did not, however, completely fade away. He had champions in high places and they tried to obtain for him the honors they thought he deserved.

In 1911 a U.S. Senate bill called for “… the erection of a statue to commemorate the bravery of Major Andrew Summers Rowan, at the War College, Washington, D.C.” Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson summarized Rowan’s service in Cuba but noted that there were places at the new War College for statues of only two distinguished American soldiers, men such as Washington, Grant, or Sherman.

A bill was introduced in the Senate in 1913 to recall Rowan to active duty as a colonel. The War Department reviewed his record, the good and the bad, and recommended disapproval, noting that. “there are in the papers in his case indications of an unfortunate temperament which unfits him to command a regiment.”

In 1914 the United States took military action against Mexican incursions along the border and Major Rowan wrote directly to the Secretary of War requesting that he be recalled to active duty as a brigadier general of volunteers. Two years later Gen. John J. Pershing led a punitive expedition into Mexico and World War I threatened America. Rowan again wrote to the Secretary of War requesting active duty as an infantry colonel. He used the red half of his typewriter ribbon to emphasize that he wanted duty “with troops at the front.”

A lack of confidence and low self-esteem were not among his shortcomings. When America entered World War I in 1917 the old war-horse was back, volunteering for active duty again, this time as a major general of volunteers. The Secretary of the Interior, the governor of Utah, and a senator wrote to endorse his request. The War Department response to all these applications was that they would consider him if they needed to recall retired officers. He was never recalled.

But Did the Inspiring Message to Garcia Even Exist?

His faults notwithstanding, Andrew Summers Rowan carried out a dangerous and important mission for his country and fought bravely in Cuba and Puerto Rico during the war and in the Philippine insurrection. Over two decades later, in 1922, his service was recognized when he belatedly received the army’s second highest award, the Distinguished Service Cross, for carrying the message to Garcia, and the third highest, the Silver Star, for gallantry in action during the Philippine insurrection.

In 1938 the Cuban government presented him with its highest decoration, the Order of Carlos Mamelde Caspedes, a gold and silver medal encrusted with precious stones, for his mission to Garcia. It also erected bronze commemorative plaques in Havana and in Bayamo, where he found Garcia. The Cubans proposed to place a bronze bust of Rowan in the Havana park where the battleship Maine was memorialized.

Exactly what was the message Rowan carried to Garcia? Elbert Hubbard described it as a letter from President McKinley but this was a fabrication. In 1903 an assistant adjutant general responded to a query about the message: “I am unable to find any record of his having carried a message to Garcia. It was probably a confidential transaction, if it occurred at all.”

The War Department referred another correspondent to Rowan’s article in McClure’s. In 1916 Edward H. Griffith of the Motion Picture Division of the Thomas A. Edison Corporation wrote to the Secretary of War requesting a copy of the message. He had just completed a five-reel feature picture in Cuba based on Hubbard’s “preachment” about the “Message to Garcia,” and wanted to include a shot of the message. The adjutant general responded that an examination of the records did not uncover any information on the text of the message. He sent Rowan’s address in Mill Valley, California, and suggested Griffith correspond directly with him.

Rowan’s Legacy

Rowan provided the answer in “How I Carried the Message to Garcia.” Before he left to find Garcia, his superior, Col. Arthur Wagner, told him the message was a series of inquiries from the President. After recalling that Nathan Hale was executed during the Revolutionary War when the British found incriminating documents in his boot, Wagner instructed, “Written communication will be avoided.” So there was no written message.

Rowan died in 1943. A hundred years ago his name was a household word and the story of his adventure in Cuba, or at least Hubbard’s version of it, was widely known. Today few Americans would recognize his name or know the story of the man who carried the message to Garcia.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments