By Michael D. Hull

Early on the morning of Sunday, October 15, 1944, a platoon of the U.S. 442nd Regimental Combat Team’s 100th Infantry Battalion (Separate) waited on a hill for its first action in the rugged Vosges Mountains of eastern France.

The 1st and 2nd Platoons of E Company had already advanced about 200 yards toward their objective, the town of Bruyeres, and the 3rd Platoon was awaiting orders. As daylight began to filter through the cold mist, the young Japanese-American GIs—many of them recent replacements—were “all nervous and on edge.” Artillery rumbled in the distance.

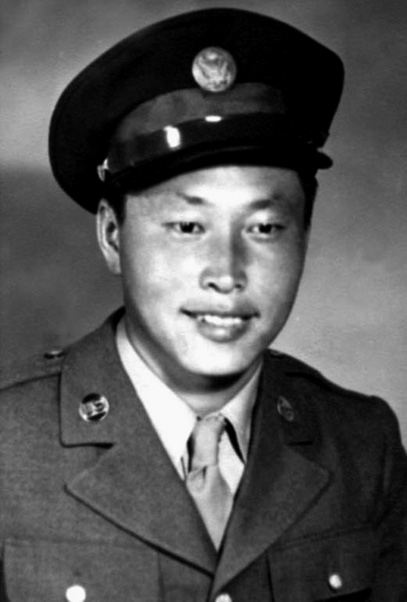

One of the bantam-sized Nisei soldiers decided to relieve the tension. Leaning against a tree next to another rifleman, he was the platoon’s good-natured “tiny runt,” Private George T. “Joe” Sakato. He jumped up, put two fingers under his nose, raised his right hand in a stiff salute, and shouted, “Sieg heil—in case we lose!” He thought his imitation of Nazi dictator Adolf Hitler would draw a few laughs, but the platoon leader was not amused.

The sound of artillery suddenly became louder, and Sakato shouted, “Incoming!” A blast blew him 10 feet through the air, and a shell fragment cut his wrist. But his buddy was dying from a neck wound. Sakato “hollered for the medics,” who “gave him some plasma, but he died on the way down the hill.”

The riflemen looked around anxiously for their lieutenant to issue orders, but he had disappeared. “He ran down the hill back to headquarters,” Sakato recalled, “or so the captain said on the radio.” Although shaken and “aching all over,” Sakato then moved forward with his platoon on the first day of the Battle of Bruyeres.

Up and down the steep, forested ridges of the Vosges Mountains during the bitter campaign of September-November 1944, Sakato and his comrades adapted quickly to the rigors of combat and fought hard against stubborn German defenses. As it had at Cassino and Anzio, the battalion took heavy losses, and its reputation became legendary in the U.S. Army. Five-foot, four-inch Sakato, who was so puny that he had to run around the walls on obstacle courses during basic training, was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, later upgraded to the Medal of Honor.

Born in 1921 in the town of Colton in California’s San Bernardino County, where his family ran a butcher shop and fruit stand, George Sakato was known as “Joe” while he was growing up. Fascinated by aviation, he liked to visit a nearby airfield, where a World War I veteran took youngsters for rides in a rickety Curtiss JN-4D Jenny biplane. Young George paid for his flights by selling newspapers and delivering The Saturday Evening Post magazine. He yearned to become a pilot but was later turned down when he volunteered for the Army Air Forces.

He was working in a grocery store when he first heard about the 442nd Regimental Combat Team. The young man tried to enlist in the Army but was rejected because of his Japanese heritage, so he returned to the grocery store.

When President Franklin D. Roosevelt lifted induction restrictions, thousands of young Nisei men of the Hawaii National Guard signed up for federal service. Formed in Honolulu and activated in Oakland, California, in June 1942, the 100th Infantry Battalion—initially comprising 29 officers and 1,277 enlisted men—was trained at Camp McCoy, Wisconsin. The battalion’s motto was “Remember Pearl Harbor.”

Shipped to the Mediterranean theater in September 1943, the battalion fought with distinction at Salerno, Monte Cassino, and Anzio. The unit’s performance, meanwhile, encouraged the Army to form another Nisei outfit, the 442nd RCT, made up of Hawaiians and mainland Japanese-Americans. Some of its volunteers were under five feet tall and weighed barely 100 pounds. Its shoulder insignia featured the liberty torch on a red-white-and-blue background, and its motto, chosen by craps players from Hawaii, was “Go for Broke” (shoot the works).

Almost as self-sufficient as a division, the 442nd RCT comprised an infantry regiment, field artillery battalion, medical detachment, and combat-engineer, antitank, cannon, and service companies. It was commanded by Colonel Charles W. Pence, a quiet, steady tactician and World War I veteran. The Nisei GIs grew to love him.

The 442nd RCT landed at Naples on May 28, 1944, and the 100th Battalion was integrated as its new first battalion. The 442nd went into action on June 26 and captured several key cities and towns, including Livorno and Pisa. The “little men of iron” melded into a topnotch fighting unit.

Although he still dreamed of going to a flying school, George Sakato, meanwhile, was drafted into the Army in March 1944 and sent to Fort Douglas, Utah. From there, he went to sprawling, swampy Fort Blanding, Florida, for basic training. After learning to fire the M-1 Garand rifle, he was sent to Camp Shelby for further training with 671 other 442nd RCT replacements.”

After less than a month at Camp Shelby, Sakato and his comrades boarded an Italy-bound troopship with field packs, duffel bags, and rifles.

On September 18, 1944, the replacements reached Naples and joined the 442nd RCT. Eight days later, the Nisei troops filed aboard Navy transports. They had no idea where they were going, but when the ships turned eastward, they knew they were heading toward southern France, where Operation Dragoon had been launched on August 15.

After landing in Marseilles, the “Go for Broke” regiment—attached to Major Gen. John E. Dahlquist’s 36th (Texas) Infantry Division—followed Highway 7 up the Rhone Valley, traveling by truck and rail to the Vosges Mountains, where the Allied armies planned to launch an offensive toward Strasbourg and across the River Rhine into Germany.

On October 14th, led by French scouts, the Nisei moved northeast to the thick Helledraye Forest, beginning a two-month ordeal of combat in chilling rain, fog, and snow. When their trucks broke down, they hiked through the mud. Accustomed to sub-tropical weather, the Hawaiians shivered. “Our coats were all wet and getting heavy,” Sakato recalled. “We had our backpacks on and our rifles, slogging in the mud.” Each of the diminutive soldiers was burdened with about 40 pounds of equipment and a 9.5-pound M-1 rifle.

On the morning of October 15, the 442nd RCT launched its attack on Bruyeres, a transportation and communications hub nestled in a valley. Aided by the 143rd Infantry Regiment, the Nisei troops led the assault because the Texas Division had been depleted by casualties, deserters, and stragglers, and, according to Dahlquist, was “very low in spirits and determination.”

The 442nd RCT’s 100th, 2nd, and 3rd Battalions soon ran into stiff opposition from well-entrenched German artillery, machine-gun nests, and powerful Mark V Panther tanks. The 100th Battalion suffered 39 casualties on the first day, and for Sakato, the advance on Bruyeres was a brutal introduction to warfare; the replacements quickly became combat veterans, and a number of them earned Distinguished Service Crosses for heroism.

Enemy resistance increased on the first day, but the GIs struggled on and made steady progress through cold winds, rain, and artillery barrages. They took 21 prisoners along with documents revealing enemy troop dispositions and learned to survive under deadly tree bursts in the dark forests by burrowing. “We cut down small trees,” said Sakato, “made logs of them to put over our foxholes, then spread pine boughs over them, and threw sand and mud over everything.” They then wrapped themselves in blankets and pup tents.

Pinned down by artillery salvos and fire from German tanks and infantry as they approached their objective, the Nisei soldiers swallowed their fears and stood their ground. As shells burst overhead and enemy infantry attacked his ridge, Sakato blazed away with his rifle “scared as hell … crying and praying at the same time.” He recalled, “I tried to crawl back into my helmet, hoping I could get out of this hell hole.”

Crawling, crouching, firing, digging in, and then starting all over again, yard by yard, the men of the 442nd RCT advanced barely two miles in three days before reaching Bruyeres on the cold, rainy morning of October 18. After more than six hours of fierce fighting, during which fortified houses and machine-gun nests were silenced, L Company of the 3rd Battalion pushed into the town and linked up with C Company of the 36th Division’s 143rd Regiment, which had entered from the south. By nightfall, the town was in American hands.

Colonel Pence’s tenacious soldiers pushed on. Near Belmont, the GIs were pinned down by German infantry and self-propelled guns. Crawling through bushes and ducking behind a fallen log, Sakato fired his Thompson submachine gun at enemy soldiers in the distance. To his astonishment, two Germans hidden on the other side of the log popped up and surrendered.

“I was stunned in terror,” he reported. But he came to his senses and took charge of the pair. Sakato had captured the first of several machine-gun nests and earned the nickname of “Machine Gun Joe.”

Besides emerging as one of the 442nd RCT’s heroes, he gained a reputation as a master scrounger. He confiscated a P-38 pistol from one of his prisoners and had taken the Tommy gun from a wrecked Sherman tank to replace his M-1 rifle. Sakato believed that a submachine gun was a more effective weapon on the tangled Vosges ridges. He collected bandoliers of extra ammunition when he got the chance.

After a two-day breather, the Nisei battalions embarked on one of the most challenging operations of World War II and their most famous exploit. They were ordered to try and relieve the 1st Battalion of the Texas Division’s 141st (Alamo) Regiment, isolated for a week on a hill nine miles inside enemy territory south of St.-Die. Surrounded by about 700 German troops, the “Lost Battalion” was in a desperate situation, with its men exhausted and low on ammunition, rations, and medical equipment. Relief efforts had failed, and supplies dropped by air fell into enemy hands.

The men of the 442nd RCT moved out in predawn darkness on Friday, October 27, 1944, advancing through dense underbrush beneath 60-foot pine trees as German artillery, mortar, and small-arms fire opened up. Brandishing their rifles, .30-caliber machine guns, bazookas, and Browning automatic rifles, the Nisei troops pushed steadily forward. They had five miles to go, and there was no turning back. While the regiment’s 522nd Field Artillery Battalion zeroed in on enemy positions, the tenacious riflemen charged ahead with hand grenades and bayonets. They disabled tanks, threaded their way carefully through nine minefields, and took more prisoners.

The GIs struggled on, trying to find their way up and down the steep, forested ridges. They each grabbed the straps on the backpack of the man ahead in order to keep together in the dense brush. “If someone in front suddenly stopped,” Sakato recalled, “there was a chain reaction all the way back.” The Nisei troops lacked winter clothing, and many suffered from trench foot.

As the going got tougher and German resistance increased, losses mounted. One of the casualties was the admired Colonel Pence, who was wounded in the back and had to be evacuated. Lt. Col. Virgil R. Miller took command. But the weary soldiers never faltered, and still more Silver Stars and Distinguished Service Crosses were earned by many acts of gallantry.

In the midst of an enemy counterattack, one of Sakato’s friends made the mistake of standing up and getting shot. “Mad as hell and crying,” Machine Gun Joe jumped out of his foxhole, grabbed his P-38 handgun and Tommy gun, and charged toward the Germans, disregarding their fire. “I’m going to get the SOB who shot him or die trying,” he told himself. He estimated that he took down “two or three guys,” but in fact he killed a dozen enemy soldiers.

Sakato was ahead of his platoon and dangerously exposed to enemy fire, so the Germans zeroed in on him with grenades. The diminutive hero kept firing until he ran out of ammunition. Left with only his pistol, he calmly “fired carefully,” killing three Germans and wounding another as they ran toward him from less than 10 yards away.

Sakato’s heroic dash encouraged his platoon to reorganize and start attacking the enemy strongpoint. The fighting was close and savage. The Germans shot a medical corpsman who was tending a soldier who had been wounded in the leg. Sakato reported, “The bullet hit the side of his helmet and spun around inside, then dropped out.” The medic’s skull was creased, but “he was fine otherwise.”

After his squad leader was killed, Sakato took charge and helped the platoon turn back an organized enemy assault and complete its mission. Besides killing a dozen Germans that day, he wounded two, personally captured four, and assisted the platoon in taking 34 prisoners.

The Nisei soldiers struggled on through intense enemy mortar and small-arms fire as they neared the Lost Battalion’s position on Monday, October 30. Machine Gun Joe hit the ground twice when mortar rounds exploded nearby, and a third blast just behind him hurled him six feet. Disoriented, he had to hurriedly dig a foxhole. He pulled his shovel from his backpack but could not raise his arm. There were holes in his pack and jacket, and blood was oozing down his back.

His tour of duty was about to end, but he would survive. He learned later that his life had been saved because he had stuffed his folded overcoat into his backpack. It had absorbed the shock of exploding shrapnel, which would have severed his spine.

Finally, after enduring great hardship and suffering 814 casualties, the 442nd RCT managed to break through to the Lost Battalion early that evening. Its surviving 211 men stumbled out of their foxholes in disbelief when they saw their rescuers, and many broke into tears. “The chills went up our spines when we saw the Nisei soldiers,” reported Lieutenant Marty Higgins, the commander of A Company of the 141st Regiment. “Honestly, they looked like giants to us.” The GIs shared K-rations and cigarettes, and the men of the 442nd RCT were dubbed “honorary Texans.”

The regiment—exhausted and reduced to half strength—was relieved on November 9th and ordered south to the Maritime Alps.

Because of their heroism and esprit de corps in the Vosges Mountains, Sakato and three comrades were recommended for the Medal of Honor, but several months later the honors were downgraded a level to Distinguished Service Crosses. Machine Gun Joe, who had reached the rank of sergeant, spent several months recovering from his wounds at hospitals and rehabilitation centers in Birmingham, England, and San Diego, California.

With the end of the European war on May 8, 1945, praise was showered on the Nisei troops for their performance in seven major campaigns. The 100th/442nd casualty toll amounted to 9,486, and 19 Distinguished Service Cross awards were later upgraded to the Medal of Honor. The regiment was the most decorated unit in American military history.

After his discharge, meanwhile, Sakato married his sweetheart, Bess Saito, and drove a truck at night to supplement his disability pension. Sakato eventually passed a civil service examination and got a job with the U.S. Post Office. A postman for 30 years before retiring in 1980, he also found time to lecture at schools, civic groups, and the U.S. Military Academy about the 442nd RCT and the forcible 1942 “relocation” of Japanese-Americans.

The Nisei hero answered a telephone call from the Pentagon in the spring of 2000, inviting him to Washington to be awarded the Medal of Honor. On the White House South Lawn on June 21 that year, Sakato received the coveted pale blue ribbon from President Bill Clinton, who paid tribute to the “extraordinarily brave” Sakato and his comrades.

Approached by a Washington Post reporter, the humble Sakato said simply, “I’m no hero, but I wear it for the guys that didn’t come back.”

The Nisei hero died at the age of 94 on December 2, 2015.

The late Michael D. Hull, author of this and many other articles for WWII History, resided in Enfield, Connecticut.