By Blaine Taylor

It was 1814. Napoleon had abdicated and the British turned their attentions to North America, where they had been at war with the Americans since 1812. They were going to make their former colonials there squirm, and maybe even grovel to re-enter the British Empire. The plan was to invade the former colonies from three points: Niagara, Lake Champlain, and New Orleans, while at the same time raiding the Chesapeake.

The Lake Champlain route, a classic invasion path going back to the French and Indian War, would divide New England from the rest of the country. The Niagara invasion might well wrest the whole Great Lakes region from the United States. The invasion at New Orleans was meant not only to block trade out of the Mississippi River but to reseize the Louisiana Territory. Linked to the invasion out of Niagara, the nascent United States would be surrounded on the north and west by British territory.

By summer, however, the Niagara invasion was checked at the battles of Chippewa and Lundy’s Lane. The raid up the Chesapeake disgraced the Americans, who had to evacuate their capital to the arsonists of General Ross. But they rallied to defend Baltimore and so end the threat in the Chesapeake Theater of the war. Then in September, Americans wrecked the plans of a formidable force in Canada by ruining the British fleet on Lake Champlain in the Battle of Plattsburg.

The Invasion From the South Continued

Admiral Sir Alexander Cochrane, who had commanded in the Chesapeake, readied his fleet at the Caribbean island of Jamaica, then sailed north to land British soldiers on the east bank of the Mississippi on December 10. These were veterans who had served under Wellington, and they thought they would have a relatively easy sojourn into the Louisiana city. Indeed, they expected many of the Spanish and French decedents never particularly wedded to American rule to acquiesce to, even champion, the British occupation. And they did not foresee much military trouble with the “dirty shirts” who emerged from the woods to form the American army.

Cochrane instructed an advance guard of 1,600 men to march to within seven miles south of the city, which was in a state of much apprehension.

But there the aggressiveness of the Americans proved decisive. Inadequately prepared with a stout defensive position, American commander Andrew Jackson immediately ordered a night attack on the newly arrived and unsuspecting British. Such a sudden night attack as Jackson now launched would not likely have happened on a European battlefield, and the British for a time were disoriented. When the firefight through the darkness was over, the Redcoats had lost four hundred dead and wounded, the American frontiersmen 24 killed, 115 wounded and 74 lost as prisoners, a total of 213. But the offensive spirit of the British was blunted, and the Americans had won time to prepare a strong defensive line closer to the city.

“The Hero of Salamanca”

On Christmas morning Sir Edward Pakenham arrived to take command of the British ground forces. Then a vigorous 38 years old, Sir Edward was known as “the Hero of Salamanca” from the Peninsular War, from which he knew most of the regiments he now commanded. The former Adjutant General to the Duke of Wellington’s Peninsular Army as well as the Duke’s brother-in-law, he was a popular and competent officer.

Considered a ruthless general in pursuit of a defeated foe, “Ned,” as he was known, served with Wellington again at Vitoria and delivered a smashing blow on the French flank at the Battle of Sorauren. Later, in order to stop plundering in Spain, Pakenham had been named head of the military police, and in this capacity went about “roaring like a lion,” according to one contemporary.

Pakenham surveyed his command on Christmas Day, 1814: six thousand British Regular Army troops and a thousand black soldiers from two West Indian units. They would face Jackson’s combined force of American Army Regulars, slaves, state militia and colorful Jean Lafitte’s pirates at a breastwork of earth, sugar barrels and some cotton bales behind an empty wide ditch—called the Rodriguez Canal—stretching three-fifths of a mile, anchored on one end by the Mississippi River, and on the other by an impenetrable swamp.

Wounded Pride

On January 1, Pakenham advanced cannon toward the American line in an attempt to bombard the fortification into submission or retreat, perhaps to assault it by infantry with bayonets if the cannonade opened an exploitable breach. But the American gunners answered in kind. They knocked out a significant number of British cannon and the Redcoat infantry had no opportunity to rush the breastwork. Pakenham had to call for a withdrawal, which, together with the night action of December 22-23, was the second wounding in 10 days of British pride and morale.

Now, faced with the prospect of a frontal attack or quitting his position and perhaps the campaign, Pakenham chose assault. But it would not quite be frontal.

His battle plan called for Col. William Thornton to cross to the west side of the Mississippi the night before the main attack and to assault a line of Kentucky militia and cannon that where supporting Jackson’s line on the east bank. If Thornton could break through the line, he would be on Jackson’s flank, though across the river. In such a position, he could at least turn the American cannon onto the rear and flank of the Americans on the east bank in aid of Pakenham’s more massive frontal attack, and perhaps force the “dirty shirt” back from the strong defensive position. Thornton’s success and consequent flanking fire was to signal the start of the more massive frontal assault on Jackson’s ditch and earthworks.

Thornton set off on the evening of January 7 with 1,500 picked Regulars. But the lack of enough adequate boats slowed the effort in ferrying the British across. Even with dawn approaching he did not have the assault forces he wanted on the west side of the mighty river.

Preludes to Battle

Meanwhile the main assault was readying. Pakenham had divided it into two columns. The primary thrust was to be on the right commanded by Maj. Gen. Samuel Gibbs. Part of Gibbs’ force was to advance without firing and throw fascines—bundles of branches—into the dry ditch affront the Americans, with a second wave carrying ladders with which soldiers could climb the earthworks and come to grips with the Americans beyond.

On the left, the attack was to be commanded by Maj. Gen. John Keane. If Thornton succeeded in silencing or turning the American cannon on the west side of the river, Keane was to assault the river side of the main American line. But if Gibbs broke the line in a significant way, Keane was to pour his troops into it. A portion of Keane’s attack, to be led by Lt. Col. Robert Rennie, was to advance up the river road on the east bank.

Several of the British units were veterans of the Washington, DC, and Baltimore campaigns; the 4th, 21st, 44th and 85th regiments. The 85th was with Thornton, and would be facing Kentucky militia. The 44th would be carrying fascines and ladders. The 4th and 21st were also with Gibbs’ column. With Keane were other crack troops, notably the 93rd Sutherland Highlanders (wearing Scottish plaid trousers or trews, not kilts as legend has it), the 95th Rifles, and two light companies of the 7th Royal Fusiliers and 43rd Monmouthshire Light Infantry, plus the West Indians. In all, the attack was mounting eight to nine thousand men against Jackson’s four thousand at the Rodriguez Canal, of which only eight hundred were regulars.

A Critical Error

Thornton’s problems during the night of January 7th were shared by others in the British Army. The men of the 44th misunderstood orders and set off in the dead of night without their fascines and ladders. By the time the error was detected and corrected, though, it was dawn, time for the sudden and surprising rush on the American defenses.

Both Gibbs and Pakenham were informed of the mistake in time to delay the attack, but Sir Edward was more worried by the lack of gunfire from across the river at the flank rear of the American line. In fact, only about a third of the 85th was in position to begin the attack up the west side of the river at 5:30, when they should have already achieved their objective.

Pakenham was urged to halt the attack because of the fascine/ladder delay and the lack of support that the thrust up the opposite bank would give. But Pakenham was frustrated with British reverses, especially the one on January 1 when he himself had called for the withdrawal. He wanted to get at this upstart general, familiarly called “Andy” Jackson, and capture the city so coveted by his men. The British have always denied it, but American legend is that the British soldiers were eager for—even promised—the “beauty and booty” that awaited them when they marched into the queen city of the South. Pakenham gave the order to fire the Congreve rocket that would signal the general assault.

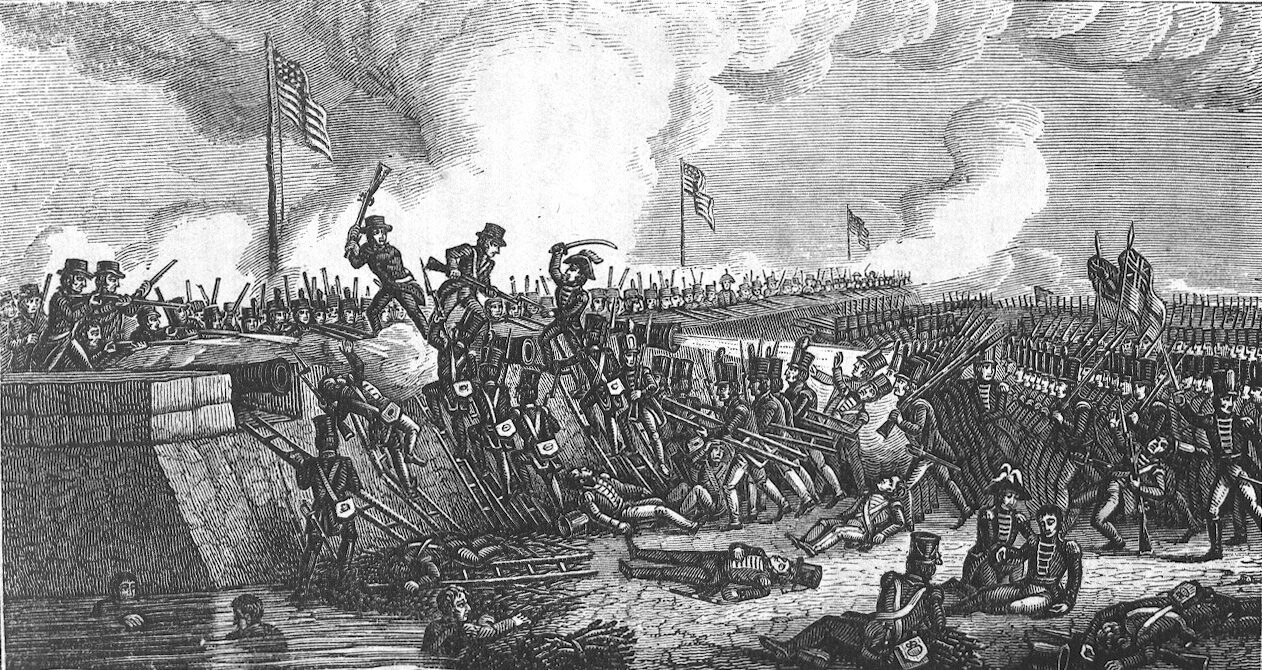

“Give It To ’Em, Boys! Let’s Finish the Business Today!”

Reportedly the first to fire on the American side was a gun commanded by one of Napoleon’s veterans from his Italian and Egyptian campaigns. Garrigues Flaugeac, and this opened up when the dimly seen Red lines were five hundred yards distant, followed by the other trio of American guns. With the bagpipes of the Scots wailing and the Congreve rockets hissing once more overhead, the Redcoats came on, until they were a mere two hundred yards from the ditch and the parapet.

For a time, the British were fortunate. Across the river, Thornton did succeed in overcoming the weak defensive line held by the Kentuckians. Colonel Rennie overran the redoubt he was ordered to reduce along the western bank of the river. But Thornton’s victory had come too late. And Rennie along with fellow officers were soon enough dead from a hail of American gunfire.

Then, as the main British lines closed on the American works, all hell broke loose as the entire line of riflemen opened up. Contrary to popular legend, it was not the Kentucky long rifles and the Tennessee squirrel guns that did the most damage, but the four artillery pieces.

Now Jackson’s voice was heard above the din shouting, “Give it to ’em, boys! Let’s finish the business today!” And they did indeed.

The Price of Impulsiveness

Returning at last with the ladders and fascines, the men of the 44th got mixed up with the main body of the advancing host, dropped the scaling gear altogether, and began firing wildly and blindly at the parapet, thus losing completely the effectiveness of their hitherto feared massed volleys. Their compatriots up front soon found themselves fired upon from both behind and ahead—or so they feared. Panic gripped the enlisted men and they broke ranks to flee.

Rushing up ahead to arrest this alarming development, General Gibbs was swiftly cut down by four American bullets. Stunned, Pakenham couldn’t believe his eyes. Lunging forward, he began waving his lieutenant general’s hat and berating the men thus: “For shame! Remember you are British soldiers!” Then, pointing to the American parapet ahead, bawled out, “That is the road you ought to take!” But Sir Edward was not able to stem the tide of retreat, and his horse went down under a hail of fire that also hit one of his knees.

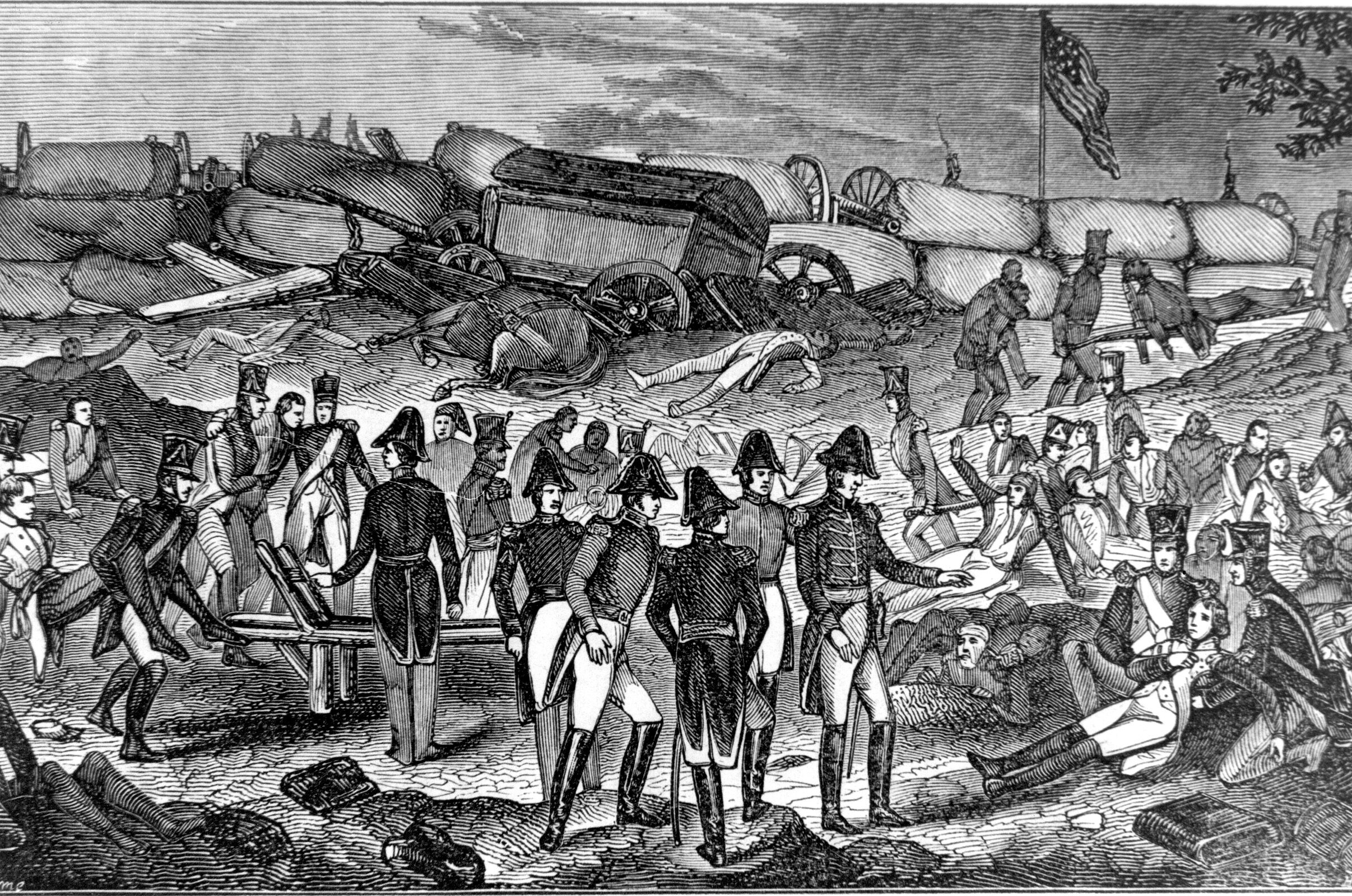

Regaining his feet once more, Pakenham seized Capt. Duncan MacDougall’s mount, gained the saddle, and was cut down again, this time his spine and groin fatally riddled. Muttering, “Tell General. …” he fell out of the saddle into the captain’s arms and died just a few minutes later. Before he, too, was brought down by wounds, General Keane screamed out, “Bayonet the rascals!” then fell.

The rest of the British army lumbered forward, into the maw of waiting death and disaster. For them, no good came of it. The British that day suffered two thousand British casualties, including Gibbs, who died of his wounds. The Americans lost only a total of 71 killed and wounded. It was an unqualified and resounding victory for General Jackson, whose line had not been breached or even scaled.

An End to the Slaughter

It now turned to Maj. Gen. John Lambert, who commanded regiments held in reserve, to take command of the British Army in the field. Despite the success of Colonel Thornton and the 85th, he halted the slaughter at 8 am. The fighting south of New Orleans was over.

A month later, Lambert captured Ft. Bowyer on Mobile Bay in an attempt to restore British fortunes in this theater of the war, but the curtain had already been lowered. Even before the battle, on December 24, diplomats in Ghent, Belgium, had agreed to end the war. Word simply had not reached the combatants south of New Orleans.

It is said that Admiral Cochrane was shattered by the news of the Treaty of Ghent. But his son, Capt. Sir Thomas Cochrane, was glad the fighting was over at last. It was too expensive a war, and now too bloody a one as well.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments