By Jon Diamond

The initial command structure in the China-Burma-India (CBI) theater of World War II produced a sharp contrast and clash of wills between two of the principal Allied leaders: British Field Marshal Archibald Wavell, and his American counterpart, Lieutenant General Joseph W. Stilwell.

The political and diplomatic rift began to develop at an important, but now almost forgotten, strategy conference held in Delhi, India, October 17-19, 1942. Whereas Stilwell was an outspoken, somewhat profane, acerbic Anglophobe, Wavell’s personality handicap was his taciturnity, which often produced conflict with his political masters, notably British Prime Minister Winston Churchill.

Wavell biographer Ronald Lewin commented on the relationship between the Field Marshal (affectionately called “the Chief”) and Stilwell: “Wavell … never grasped the fiery inner quality of a man who was dedicated to carrying out a mission…. Amity was not increased when Wavell, for an appreciable period, withheld his forward plans from Stilwell—fearful, no doubt, of leaks in the Chinese camp…. In Stilwell’s mind, Wavell’s heart was not in the fight—or if it was, then some selfish interest of the Limeys must be involved … there was a conflict between British realism and American euphoria from the start.”

Wavell did not share Stilwell’s strategic optimism for a counter-offensive in Burma after the Allied defeat and “Walkout” of 1942. At an Indian press conference after his escape from Burma in April 1942, Stilwell plainly stated, “I claim we got a hell of a beating. We got run out of Burma and it is humiliating as hell. I think we ought to find out what caused it, go back and retake it.”

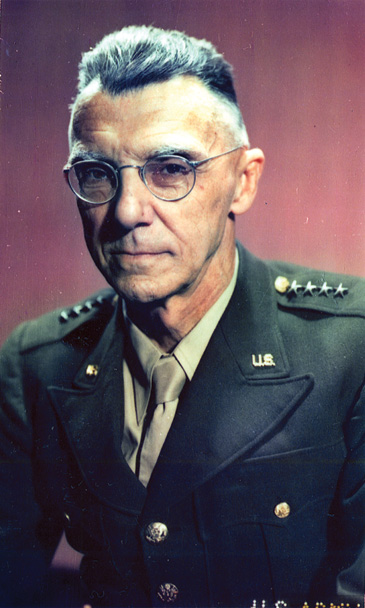

Born in 1883, General Joseph Stilwell was a 1904 graduate of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. By the time World War II erupted, he had gained extensive experience in the Pacific and Asia, including service in both the Philippines and China. From 1935 to 1939 he served as the American military attache and ranking colonel to the Chinese government. Stilwell was well acquainted with Chinese Nationalist leader Chiang Kai-shek and was a logical choice to lead American forces in the China-Burma-India Theater as U.S. military involvement on the Asian continent increased.

On December 7, 1941, the day Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, Stilwell was the commander of III Corps, defending southern California. Late in December, Stilwell reported to Washington, suspecting that he was to be given the command to invade North Africa under a “Europe First” strategic program. However, General Marshall viewed the defense of the China Theater, later renamed the China-Burma-India (CBI) Theater, to be more urgent in order to keep Chiang in the fight, as well as being “the most-impossible job of the war.”

Ultimately, both Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson and Marshall knew that Stilwell was their man. Stilwell was invited to Stimson’s home on January 10, 1942, where he was told, “The finger of destiny is pointing at you,” and that its direction was China.”

Stilwell was sent to the CBI Theater in February 1942, with many titles, including: Chief of Staff to the Generalissimo, Commander of American Forces in the CBI, and administrator of Lend-Lease to improve the combat efficiency of the Chinese Army.

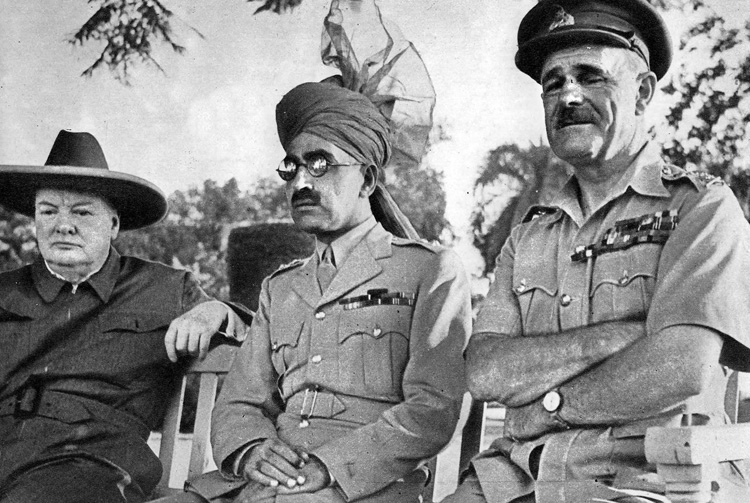

Born at Colchester in 1883, Field Marshal Archibald Wavell was a member of a family with long military ties. He attended the Royal Military Academy at Sandhurst for only a year in 1900, since the curriculum was truncated to produce junior officers for the Boer War. He served with distinction during World War I and was seriously wounded at Ypres in Belgium in June 1915, losing his left eye. After commanding British and Commonwealth forces against the Axis in the Middle East and North Africa, he was relieved of command by Prime Minister Winston Churchill in June 1941 and subsequently transferred to the Far East.

On December 12, 1941, Churchill informed Wavell that with the outbreak of war with Japan he would be responsible for Burma. At Chungking in early 1942, Chiang Kai-shek offered Wavell two Chinese “armies” for use in Burma (a Chinese army was equivalent in size to a British or Indian Army division). Wavell accepted only one “army,” and asked that the other, which was assembling around Kunming, remain there, best placed as a strategic reserve to move into Burma if needed or to defend Yunnan against a Japanese assault from Indochina aimed at cutting the Burma Road.

Nevertheless, his decision had the appearance of spurning the offer of Chinese help and inflicted a loss of “face” on Chiang. It seemed to imply that Wavell lacked confidence in the Chinese troops offered to him.

According to Churchill’s war memoirs, as a result of a meeting with Wavell in Chungking, the Generalissimo “complained to President Roosevelt of the British commander’s [Wavell’s] apparent lack of enthusiasm about any contribution China could make.” In a cable to Wavell on January 23, 1942, Churchill opined, “You have, I understand, now accepted 49th and 93rd Chinese Divisions, but the Chinese Fifth Army and the rest of the Sixth Army are available just beyond the frontier…. I cannot understand why we do not welcome their aid…. The American Chiefs of Staff insisted upon Burma being in your command for the sole reason that they considered your giving your left hand to China and the opening of the Burma Road indispensable to world victory…. If I can epitomize in one word the lesson I learned in the United States, it was ‘China.’”

Thus, Wavell had been notified that American senior commanders considered the maintenance of a land route through northern Burma to China of the highest importance. In Wavell’s defense, he replied to Churchill’s missive, “I did not refuse Chinese help. I accepted both these divisions when I was at Chungking on December 23rd, and any delay in moving them down has been purely Chinese. These two divisions constitute Fifth Chinese Army, I understand, except for one other division of very doubtful quality. All I asked was that Sixth Army should not be moved to Burmese frontier, as it would be difficult to feed…. I am aware of American sentiment about the Chinese, but democracies are apt to think with their hearts rather than with their heads, and a general’s business is, or should be, to use his head for planning…. I agree British prestige in China is low, and can hardly be otherwise till we have had some success. It will not be increased by admission that we cannot hold Burma without Chinese help.” Churchill replied to Wavell that they were in agreement.

Wavell met with Chiang in early March 1942 to arrange for movement of the Chinese Fifth and Sixth Armies into Burma, which was now of vital military importance, despite earlier seeming to be indifferent to their use.

Stilwell’s views on the use of Chinese infantry differed sharply from Wavell’s. Unlike Wavell, Stilwell knew the Chinese well, having worked arduously for several months as an engineering adviser after being posted to Peking in 1920. This experience would serve Stilwell well, because 20 years in the future he would train new Chinese divisions in India for eventual combat to wrest the Hukawng and Mogaung valleys from the Japanese and supervise a vast construction project, the Ledo Road, throughout north Burma to reopen a land route to China.

In late March 1942, Stilwell had arrived from China to take command of the Fifth and Sixth Chinese Armies in Burma. However, disaster after disaster befell Wavell’s defense against the Japanese juggernaut intent on capturing Rangoon and Mandalay as well as severing the Burma Road before wheeling westward toward the Chindwin River on the border with Assam, India.

By the end of April, part of these Chinese forces withdrew into China; the rest followed General Stilwell up the Irrawaddy River, but with Myitkyina about to fall they moved west across the Burmese jungles and mountain ranges to India to avoid capture. The Burma Road, the only land route between India and China, was now severed. It would remain Stilwell’s burning mission to reoccupy northern Burma.

The British, however, were just not interested in fighting for northern Burma, especially if it compromised the defense of the eastern Indian states. The British strategy in Asia involved an eventual seaborne effort against Rangoon with a northward advance to open the Burma Road, enabling them to focus on the recapture of prewar British colonies.

Wavell respected Stilwell; however, he did not realize the manic goals that the American was trying to achieve. As summarized by Lewin, “To train and arm the two good Chinese divisions which had escaped into India (the 38th and 22nd), to create from scratch another 30 out of Chiang’s raggle-taggle swarms, to master-mind nothing less than a military revolution in the forces of a corrupt, apathetic and incompetent ally—such was the substance of Stilwell’s reveries. It is not surprising, therefore, that when he and Wavell came together to concert their plans, in a series of meetings which started on 17 October [1942] each received a shock. The truth is that there was a mutual incomprehension.”

Stilwell had been formulating a plan after the defeat in Burma as early as July 1942. He prepared a memorandum on operations utilizing his two Chinese divisions (the 38th and 22nd) proceeding from Ledo in India’s northeastern mountain country along with three British divisions attacking eastward from Assam across the Chindwin River. He was optimistic that he would also get some American ground forces to participate. In addition, a dozen of Chiang’s divisions would strike westward from Yunnan. These separate Allied drives would converge above Mandalay, then fan out across south Burma, capturing Rangoon and Thailand with a final move to the coast of Indochina.

The campaign that Stilwell proposed with Rangoon as the main Burmese objective was to incorporate a British seaborne effort as well to open that port to shipping. The entire operation was codenamed Anakim.

At a strategy conference in Delhi on October 17-19, 1942, the first two conference days were not satisfactory from Stilwell’s point of view. Wavell shared with Stilwell both his pessimism about Anakim and his reluctance to increase the number of Chinese troops training in India. These contentious issues had been festering for months, and now a fissure had formed in the upper echelon of the Allied command in India that would spread to London and Washington.

Lewin noted, “Wavell was already convincing himself and the Chiefs of Staff that even the British plan for Anakim was premature and could not be set in motion until the autumn of 1943.”

In fact, Wavell had warned the War Cabinet that in regard to Rangoon, he would not have built up the necessary forces, especially airpower, for the operation. In Delhi, Wavell described for Stilwell his initial plans for a campaign in Burma within the confines of his logistic and communication problems in Assam as well as high illness rates among his troops. He added that aircraft, troops, and equipment had been diverted to the Middle East and North Africa rather than their original destination, India.

Thus, Wavell only proposed moving south, down the Arakan coast, with the intent to seize Akyab. Rangoon could be the initial phase of later operations against the Burmese port city.

Wavell further objected to any increase in the number of Chinese trained and based in India, citing limited resources and transportation capabilities.

Maybe Wavell’s fear of large numbers of Chinese troops was based on suspicions of Chiang’s view toward the British Empire’s claim to Burma. Historian and Stilwell biographer Barbara Tuchman claimed, “In July 1943, the Chinese Ministry of Information published a map which revived ancient claims to include all north Burma as Chinese territory.”

On the third day of talks with Wavell, Stilwell found a remarkable change in the British field marshal’s attitude. “They will give us a sector at Ledo. They will supply us…. Everything is lovely again, so obviously George [Marshall] has turned on the heat.” Apparently, both Field Marshal Sir John Dill and General Marshall urged the British War Cabinet to order Wavell to increase the number of Chinese troops in India.

According to one account, Wavell “got religion” on October 19 and in an about-face recognized as a basis for planning the proposal by Stilwell and Chiang for retaking northern Burma as well as Rangoon in 1943 along with increasing Chinese troop training in India under Stilwell. A joint planning committee met for the first time on October 22, and Stilwell informed the group that it would be safe to work on the assumption that the Chinese Army in India would operate from Ledo.

Wavell designated the Hukawng Valley as Stilwell’s sector, with the objective of capturing Myitkyina and making contact with Chinese troops advancing west from Yunnan. Myitkyina and its all-weather airfield was the ultimate prize in order to negate Japanese fighter interdiction of Allied transport aircraft flying the famous Hump. Finally, the Americans were to construct a road from Ledo over the Pangsau Pass, down the Hukawng and Mogaung valleys to Myitkyina following the advance of the 38th and 22nd Chinese divisions, and link with the Old Burma Road.

The British in Delhi had no confidence that Stilwell would be able to achieve this strategic goal. Furthermore, the British did not want the Ledo Road and viewed it as an expensive and labor-intensive project of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s “Support China” policy. Looking at a broader imperial strategy, Tuchman contended that “Britain would have preferred to maintain the roadlessness of the frontier in the interests of the shipping monopoly, and even more because they wanted no access to India for the Chinese. They agreed to the road on paper because of Washington’s insistence and because open refusal would have antagonized the Chinese more than ever, but they never ceased to oppose and obstruct it behind the scenes…. ”

It is intriguing that the British Official History, The War against Japan, does not address the Stilwell-Wavell conferences in Delhi in October 1942 in any length. It simply states, “His [Stilwell’s] object was to train and equip a Chinese corps of two divisions and corps troops, which would eventually be used to advance from Imphal to join hands with the Chinese from Yunnan. Wavell accepted this proposal in October 1942 but, considering that an advance from Imphal was impracticable, directed that one should be made from Ledo by the Hukawng Valley to Myitkyina. The necessary equipment, transport and training staff would be provided from American, and the accommodation and rations from British, sources. The transport of Chinese troops by air to bring the divisions up to strength began immediately.”

Stilwell’s mission had the President’s and General Marshall’s support, as indicated by a February 25, 1944, memorandum from Roosevelt to Churchill: “I have always advocated the development of China as a base for the support of our Pacific advances, and now that the war has taken a greater turn in our favour … it is mandatory therefore that we make every effort to increase the flow of supplies into China. This can only be done by increasing the air tonnage or by opening a road through Burma. Our occupation of Myitkyina will enable us immediately to increase the air-lift to China by providing an intermediate air-transport base as well as by increasing the protection of the air route. General Stilwell is confident that his Chinese-American Force can seize Myitkyina by the end of this dry season.”

The wrangling between Wavell and Stilwell eventually contributed to a restructuring of the Allied command in the CBI. Soon enough, the long fight to defeat the Japanese was underway in earnest.

Jon Diamond is a frequent contributor to WWII History. He has recently completed Osprey Command Series books on Orde Wingate and Archibald Wavell.