By Victor Kamenir

Egyptian medieval chronicler Ibn Taghribirdi relates an incident that occurred following Turco-Mongol Emir Timur’s conquest of Aleppo in 1400. A young man in the city’s Mamluk garrison was found lying among stacks of dead and dying soldiers after the Turco-Mongols captured the city. Timur learned that the young warrior had fought with such ferocity that he had suffered 30 cuts from Turco-Mongol sabers. Timur “marveled extremely at his bravery and endurance, and, it is said, ordered that he be given medical treatment,” wrote Ibn Taghribirdi.

Timur generally ordered captured soldiers executed, thereby removing the possibility of their joining his conquering army, but on occasion he welcomed into his ranks those who had fought with great loyalty for their masters and commanders. It was a glimmer of humanity in the famous conqueror’s otherwise sadistic nature.

Timur was born on April 9, 1336, near the town of Kesh in modern-day Uzbekistan to a prominent family of the Barlas clan. The Barlas clan was at the forefront of internecine struggle for control in the fractured Mongol khanate formerly belonging to Genghis Khan’s second-oldest son, Chagatai.

By the time of Timur’s birth, the Chagatai Khanate, which at one time encompassed parts of a half-dozen Central Asian states, had broken into two halves. Turkic-speaking tribes of the Tatar Confederacy in the western half—known as Transoxiana—had come under the cultural and religious influence of the neighboring Persians. As a result, they had shed their Mongol identity and converted Islam. Meanwhile, the peoples of the eastern half, known as Moghulistan, retained their Mongol character and its nomadic way of life. Even so, the ruling elite of these Moghulistan also converted to Islam.

Although he received scant formal education, Timur grew up an intelligent, astute, and somber young man. He possessed great skill at arms, and he had a knack for the backstabbing politics endemic to the harsh, remote lands of Central Asia.

A power vacuum existed in Transoxiana following the assasination of Emir Qazaghan in 1358; seeking to exploit the situation, Moghul Khan Tughlugh invaded and subjugated the tribes of Transoxiana. Tughlugh Khan subsequently installed his son Ilyas-Khoja as viceroy and returned to Moghulistan.

Timur, who was extremely ambitious—having grown up in the shadow of Genghis Khan’s legend—offered his services to the new viceroy. But other than being granted control of his native Kesh, Timur was thwarted in his aspirations to receive a senior position in Ilyas-Khoja’s court. Deeply disillusioned by the political setback, Timur went into self-imposed exile with his household and a number of Barlas clan warriors who were loyal to him.

Timur ventured south into Afghanistan, where he joined his brother-in-law Emir Husayn of Balkh. Timur and Husayn’s situation mirrored that of Italian condottieri, who offered their swords to powerful feudal lords and organized their armies. While in the service of the Prince of Seistan in eastern Persia in 1363, Timur was struck by a volley of arrows during a minor skirmish. One arrow penetrated his right knee, while another injured his right elbow. Neither wound healed correctly, leaving Timur with a pronounced limp and a diminished use of his right arm, earning him the nickname Timur the Lame, or Tamerlane, as he came to be called by Europeans.

The steadily growing reputations of Timur and Husayn drew to their banners warriors looking for loot and glory. After building up sufficient strength, the two emirs returned to Transoxiana sometime in mid-1360s. After initially suffering a defeat, they eventually routed Ilyas-Khoja. As a result, Moghulistan withdrew its forces from Transoxiana.

Even with the Mongols gone, however, Turkic lords could not oppose the firmly entrenched tradition of having a descendant of Genghis Khan upon the throne of Transoxiana. Timur and Husayn found a sufficiently pliable—and weak—member of the Genghizid line named Siurgutamysh to be the titular khan, while they held the real reins of power, maintaining their titles of Emir, the equivalent of “commander” or “general.”

After the death of his father Tughlugh Khan, Ilyas-Khoja consolidated his power in Moghulistan and made another attempt at Transoxiana. On May 22, 1365, the combined forces of Timur and Husayn met Ilyas-Khoja on the bank of the Chirchik River. The relationship between the two emirs had deteriorated, and they could not agree on conduct of the campaign. Even though Timur’s and Husayn’s joint forces numbered 85,000 men against Ilyas-Khoja’s 60,000, they fought as two separate entities without supporting each other.

During the battle, a sudden rain turned the battlefield into a muddy morass, with horses sinking up to their knees in the mire. The battle in the mud became a brutal melee, and Ilyas-Khoja succeeded in defeating the two emirs. Losing more than 10,000 men, Timur and Husayn retreated past Samarkand. In their assessment, the city’s garrison had sufficient strength to withstand a siege. Ilyas-Khoja subsequently besieged the city but was forced to abandon the effort when an epidemic broke out among his forces.

Timur and Husayn took joint control of Samarkand. During this time, Timur drew upon his power base in nearby Kesh, but Husayn was the more powerful of the two. He dealt harshly with the local aristocracy; for example, by imposing burdensome taxes. In contrast, Timur showed his political astuteness by working steadily to undermine Husayn’s influence. Their alliance of convenience disintegrated upon death of Timur’s wife, who was Husayn’s sister. At that point, their hostility erupted into open warfare. After suffering initial defeat, Timur negotiated a truce that allowed him to return to Samarkand, while Husayn returned to his power base in Balkh.

Timur made his move against his erstwhile ally in 1370. He suddenly appeared in Balkh, catching Husayn unprepared. The two rivals skirmished for two days. Husayn agreed to surrender after securing Timur’s promise not to execute him. Sticking to the letter of their agreement, Timur had one of his officers behead Husayn instead. Timur’s troops then sacked Balkh and massacred the majority of its population. The incident foretold the wholesale slaughter that was to become Timur’s trademark of conquest.

Timur called for a council of tribal leaders and senior generals, known as a kurultai. Timur had Genghizid Siurgutamysh, his puppet ruler, confirmed as the Khan of Transoxiana. Everyone in the region knew, though, that Timur held the real power. He took as his title Grand Emir. Siurgutamysh, and his son who succeeded him, were well-treated but virtually powerless.

Timur established Samarkand as the capital of his new state, which he called Turan. As part of celebratory proceedings, he married Husayn’s widow, Saray Mulk-Khanum, who was a descendant of Genghis Khan. In this way, he was able to gain an aura of legitimacy by tying himself to the Genghizid line through marriage. In order to maintain a veneer of legitimacy, Timur styled himself a cultural successor to Genghis Khan, attempting both to restore the great man’s former empire and to unify the world under one Islamic ruler.

Timur then began calling himself Timur Gurgan, which translates to “son-in-law.” Timur also established the practice of taking wives and daughters of defeated opponents as his own wives and concubines. In this way, he eventually amassed a harem of 18 wives and 25 consorts.

Despite these moves, his new state stood on shaky ground. Its neighbors, all independent fragments of Genghis Khan’s once-sprawling empire, were either wary or openly hostile to Timur’s growing power. Timur conquered Khoresm, to the west, with minimal resistance. He arranged the marriage of its princess to his oldest son, Jahangir.

By this time Moghulistan was also in a state of anarchy, and raids by various chieftains were a constant nuisance for Transoxiana. Between 1371 and 1390 Timur conducted seven campaigns to keep the Mongols at bay, which required him to interrupt his campaigns in southwestern Asia to return east. The powerful Dughlat clan, under Emir Qamar-ad Din, proved particularly troublesome. Although Timur was never able to completely subjugate Moghulistan, his campaigns ruined the hostile state and broke the power base of the Dughlat clan. After his defeat, Qamar ad-Din went into exile. A period of instability followed before another Moghulistan ruler established a wary peace with Transoxiana.

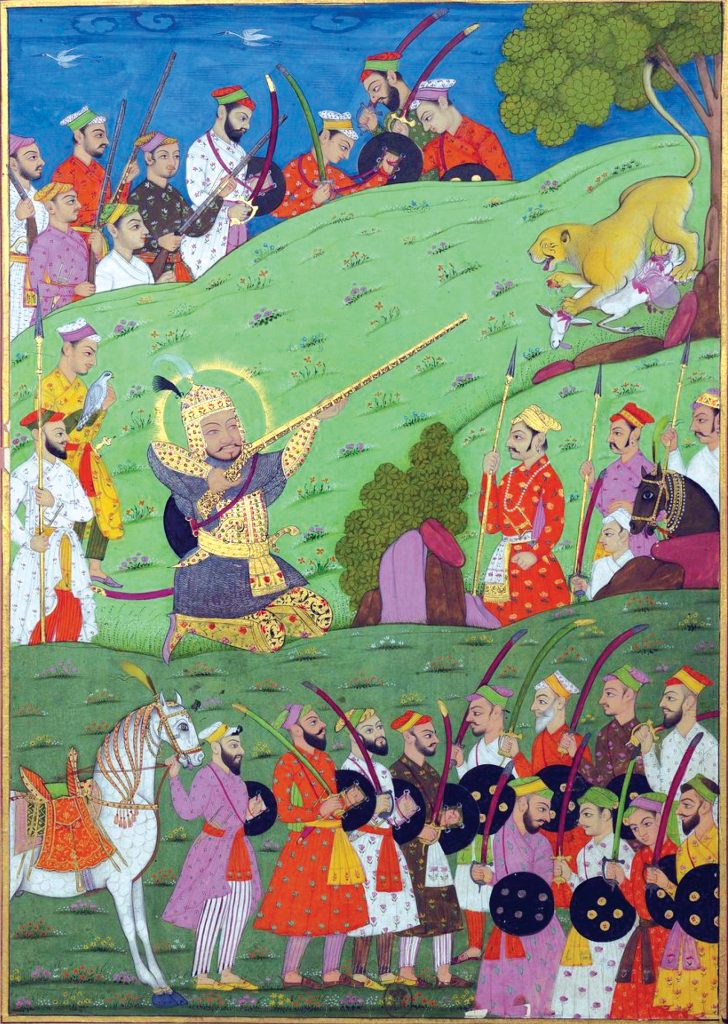

Timur’s Turco-Mongol army was not much different from that of Genghis Khan. It was largely composed of members of Turkic-speaking clans, who had converted to Islam; the Europeans called them Tatars. The backbone of the army was its tribal horse archers, who were backed up by heavy cavalry wielding both bow and lance. The horse archers’ primary weapon was a composite bow. They used one type for long range and another for close-in, rapid shooting.

“Only a hand that can grasp a sword may hold the scepter,” states a Tatar proverb. The timing was ripe for Timur to realize his ambitions: In the first half of the 14th century, the Black Death swept from Asia to Europe. As it spread like wildfire across the continents, it decimated populations and weakened established social orders. Hence, the collapse of the Il-Khanid Mongol dynasty in southwestern Asia created a power vacuum in Persia among warring successor states.

Ruy Gonzales de Clavijo, the Castilian ambassador at Timur’s court, gives a good summary of the Tatars’ discipline in battle. “Ranks formed without word of command, orders were anticipated before drum or trumpet sounded,” he wrote. “Good order is maintained with utmost strictness, and none dare fight with another or oppress his neighbor by force; indeed, as to fighting, that Timur makes them do enough, but abroad.”

Timur’s army trained regularly, and he conducted spot inspections even while campaigning. Yearly training culminated in winter with maneuvers called the nerge, which meant “great hunt.” Units spread out in a line that extended 50 miles. The wings would then move steadily forward, all of the while curving inwards until they met forming a circle. Close coordination was required to prevent the animals from escaping, and any man permitting even smallest creature to slip through was severely punished. Once the animals were corralled, the hunt could not commence until the hunt commander made the first kill.

In Timur’s army, sedentary city populations typically served as infantry, although their role was largely limited to defensive tasks and siege works. Timur used the traditional nomad decimal system to organize his armies. Senior leadership positions were appointed based on tribal nobility, skill, loyalty, and fearlessness. As for the warriors, they could earn promotions through merit.

During campaigns, the swift-riding Turco-Mongol cavalry were followed by trains bearing Timur’s court, administrators, and some of his wives. In addition, Timur’s troops brought with them huge herds of horses and cattle.

Timur’s campaigns resembled large-scale raids rather than empire-building conquests in the mold of Genghis Khan. After conquering a territory, Timur typically headed back to Samarkand, carrying with him looted treasures, slaves, and skilled artisans. The army left in its wake devastation, destroyed infrastructure, and dead towns full of decomposing bodies. His conquests were characterized by escalating levels of brutality toward defeated populations. Timur, who was a Muslim more from convenience than anything else, made no distinction between Muslims and peoples of other religion. Although not specifically intending to do so, Timur’s conquests decimated the once-thriving Nestorian Christian communities of the Middle East.

Unlike Genghis Khan, who commonly incorporated defeated states into his empire proper, Timur made little effort to establish effective administration over conquered territory. He frequently left defeated rulers to govern in his name. Timur justified the bloodshed he inflicted during his campaigns on the grounds that it was necessary to terrorize the enemy in order to prevent resistance. This policy, though, frequently backfired. When Timur departed conquered cities, he often had to return to quash uprisings. The end result was enormous bloodshed. When a massacre was in the offing, Timur would order his men to raise a black banner over his tent.

After establishing control over Transoxiana, Timur turned his attention in 1381 to Khorasan. The following year he invaded the Mazandaran region of Persia on the southern shores of the Caspian Sea. The Il-Khanate, another successor state of Genghis Khan’s empire, had disintegrated long before Timur’s birth and was split among several mutually hostile dynasties. The Il-Khanate encompassed eastern Anatolia, Persia, northern Iraq, Afghanistan, and Baluchistan. After its collapse, what remained were a half dozen weak sultanates and principalities. Timur focused much of his wrath in this campaign against Sultan Emir Wali of Mazandaran because he had attacked one of Timur’s vassals in Khorasan.

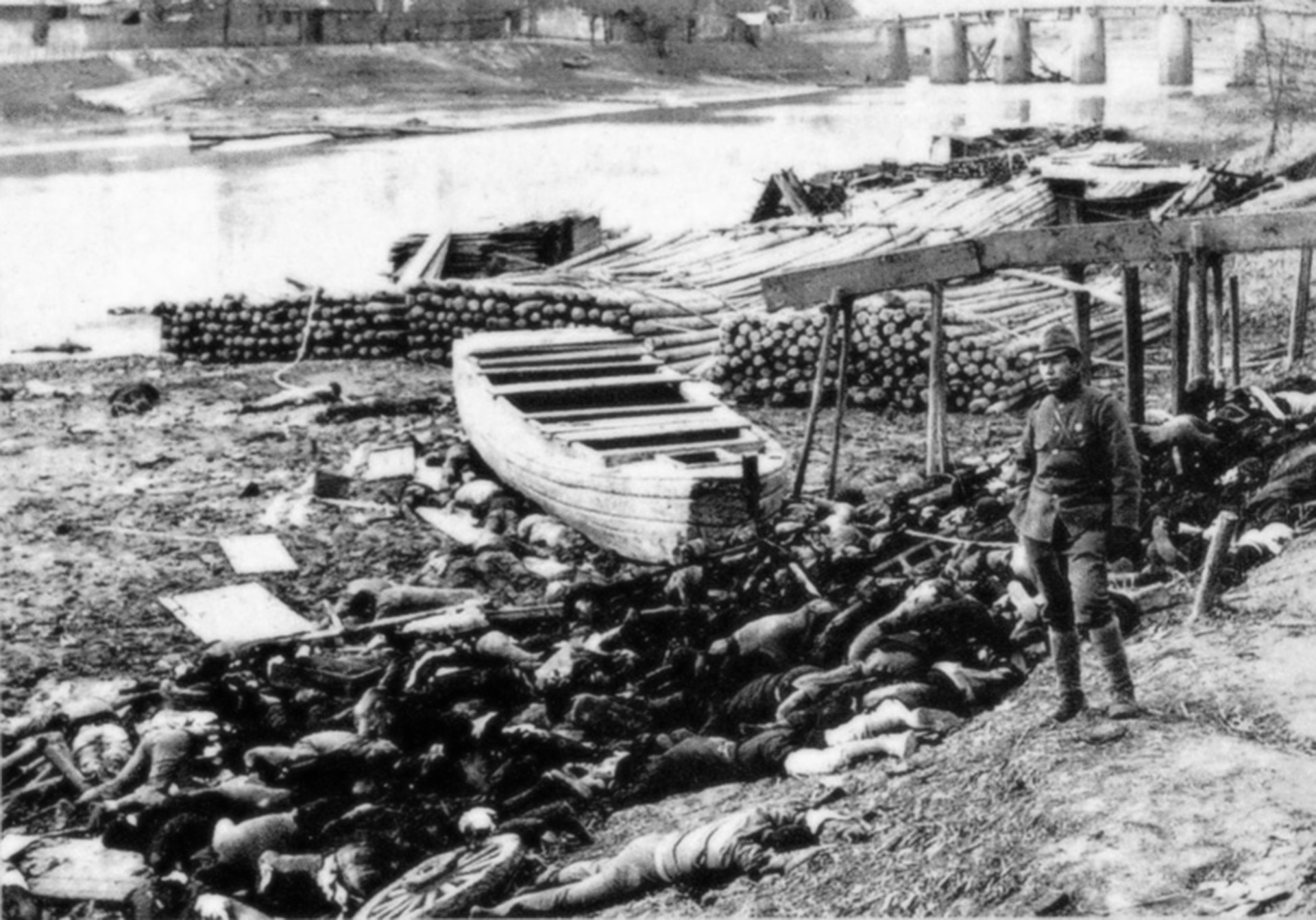

Timur’s Tartars massacred 100,000 people at Heart in Khorasan. To ensure that all of his men participated in the bloodbath, he ordered that each warrior was to produce a head. His troops stacked the severed heads into 28 pyramids. As if that were not brutal enough, he ordered his men to cement 2,000 of the residents into the city walls while they were alive. Lives were not the only things lost in the devastation of the city, for Timur’s men also destroyed agricultural infrastructure. Before marching away from Heart, the Timurid troops leveled the ancient city.

Timur worked ceaselessly to bring glory and prosperity to his beloved Samarkand and the core of his empire. Attracted by favorable treatment and high pay, skilled architects and masons flocked into Timur’s service in Samarkand. Of course, Timur’s troops compelled many others, brought from the far corners of his empire, to work by threat of force.

The buildings of Samarkand, which previously had been made mostly of clay, were replaced by magnificent, enduring stone structures. The artisans built palaces, arches, mausoleums, and mosques. When Timur passed through Samarkand as he marched back and forth against enemies in the east and west, he would inspect the buildings in his capital. If he found a building did not meet his exacting standards, he ordered it destroyed and rebuilt.

In the early 1380s, Timur helped a Genghizid prince named Tokhtamysh gain control of the Golden Horde. Ghengis Khan’s grandson Batu had founded the Golden Horde, which he established when he inherited western half of his grandfather’s dominions.

Batu’s vast khanate included most of European Russia. During his military campaigns in the mid-13th century, Batu extended control over a domain that stretched from the Urals to the Carpathians. The khanate’s name came from an occasion when Batu pitched his golden tent at Sarai on the Volga, thus founding the center of his khanate. Timur tracked closely events in the Golden Horde, for it bordered Transoxiana, the heart of the Timurid Empire, to the northwest.

Prince Tokhtamysh repaid Timur’s assistance with betrayal. While Timur was engaged elsewhere in 1386, Tokhtamysh began raiding northwestern Persia, which was part of the Timurid Empire. Turning the wrathful eye toward Tokhtamysh, Timur attacked in a wide flanking maneuver around the western edge of the Caspian Sea through the Kingdom of Georgia.

While Tokhtamysh retreated north of the Caucasus Mountains, Timur defeated Georgia. In so doing, he forced King Bagrat V to convert to Islam at sword-point and swear allegiance to him. Returning to Samarkand, Timur left Bagrat in nominal power under his suzerainty. He furnished him with 12,000 Turco-Mongol troops in case Tokhtamysh returned. Shortly after Timur’s departure, Bagrat and his son, George VI, began waging a guerilla war against the Tatars, resulting in widespread devastation in Georgia.

Tokhtamysh returned in 1387 to attack Transoxiana, besieging Bukhara, the second city in Timur’s empire. As Timur drew near, Tokhtamysh once again withdrew to the steppes to the north. The city of Urgench in Khwarizm paid a heavy price for supporting Tokhtamysh; Timur ordered the massacre of its people and the destruction of the city.

After securing his flanks, Timur moved against Tokhtamysh in February 1391. After an epic chase that lasted 18 weeks and covered 1,800 miles, Timur cornered Tokhtamysh on the Kondurcha River, which lay just north of modern Samara in Russia. Losing a large part of his force, Tokhtamysh fought his way out of the trap and escaped again.

Rebuilding his strength, Tokhtamysh began raiding Georgia in 1395, forcing Timur to go after him in earnest. The two armies squared off again along the Terek River on April 15, 1395. Tokhtamysh held the only available ford; Timur knew it was suicide to attack across the river against a waiting enemy, so he led his troops upstream along the south bank, while Tokhtamysh shadowed him along the north.

The maneuvering lasted for three long days with neither army gaining an advantage of position. “On the third night, as soon as his camp was formed, Timur issued orders that all the women who had marched with his soldiers should don helmets with men’s war gear to play the part of soldiers, while the men should mount and forthwith ride back with him to the ford, each horseman taking a second mount by the bridle,” wrote Clavijo. The following day, Timur’s army forded the river. It marched along the north bank unnoticed and launched a surprise attack on the enemy. Timur’s horse archers routed Tokhtamysh’s troops and plundered their possessions.

Tokhtamysh escaped once again, but this time his power was broken for good. In retaliation for Tokhtamysh’s impudence, Timur ravaged the Golden Horde’s territory. His horsemen sacked and destroyed Sarai. After pushing on to destroy the town of Yeletz on the Russian frontier, the Tatars turned south to Crimea, where they destroyed all of the Genoese trading posts along the Black Sea littoral before heading to their homeland via Georgia.

With his power base and sources of income destroyed, Tokhtamysh fled to Lithuania, where he died ten years later. Iduku, who succeeded Tokhtamysh, could not restore the power of the Golden Horde. This enabled the Russians to finally throw off the Mongol yoke after 200 years, which led to the rise of the Grand Duchy of Moscow. The destruction of Sarai and Astrakhan disrupted the northern fork of the Silk Road, rerouting merchant traffic and resulting in rich revenues flowing southward through Timur’s territory. Survivors of Genoese colonies carried the word to Western Europe about a new nomad scourge, that of the Tatars, emerging in the east.

Having nullified the threat from the Golden Horde, Timur returned to Samarkand in 1396, where for the next two years he fully immersed himself in turning his capital into a jewel of Central Asia. While the architectural wonders were being built, Timur was preparing for new campaigns. He cast his gaze to the south, eying India, which was ripe for an invasion given that it had been weakened by a long-running civil war between Muslim sultanates and Hindu kingdoms. In preparation for an invasion of India, forward detachments were sent to reconnoiter the ground and assess the combatants in preparation for a major campaign.

Timur led 90,000 troops across the Indus River in September 1398. He was bound for Dehli, and as he marched the towns and fortresses in his path toppled like dominoes. Timur alleged that his Sultan Nasiruddin Mahmud of Delhi, who was also a Muslim, was being too lenient toward his infidel Hindu subjects.

Timur’s army approached Delhi in late December. Mahmud had done an admirable job of fortifying his city; it was defended by a strong garrison. Upon his arrival, Timur began making preparations for a lengthy siege. He established a fortified camp a short distance from the city. His men constructed a ditch around it, and the excavated earth was topped by a wooden palisade. Timur brought tens of thousands of prisoners from the villages he had conquered along the way to slaughter before the gates of the city. He did this both as an intimidation tactic and to eliminate the need to guard and feed them.

The need to garrison the towns and fortressed that he had captured on his march to Dehli had reduced Timur’s army close to parity with Mahmud’s army. Foregoing the advantage of his fortified position, Mahmud marched his army outside the walls to face Timur in the field on January 2, 1399. Timur faced a major battle, for Mahmud fielded 10,000 cavalry and 40,000 infantry. Mahmud’s army also included 100 war elephants, a fearsome asset that Timur’s tribal steppe horsemen had never faced in combat.

The Dehli Sultanate’s troops protected their elephants with padded armor and equipped them with blades fitted over their tusks. The elephants served a dual purpose, both as missile platforms and command platforms. The elephants bore carriages upon their backs that could carry as many as seven warriors equipped with spears and bows. Their height enabled the warriors to observe enemy positions and signal intelligence about them to other forces. But elephants had a major drawback: They were skittish and prone to being spooked by sights and odors to which they were unaccustomed.

Timur devised a method to deal with war elephants. He knew that all animals, no matter how large, have a deathly fear of fire. Timur ordered his troops to outfit a number of camels and water buffaloes with bales of straw and other flammable materials that could be quickly set afire.

On the morning of the battle, the Dehli Sultanate’s army deploy for battle with two wings and a center. Mahmud ordered the elephant troops to take up positions in front of the infantry in the center of his army. As for Timur, he deployed his troops in two battle lines. He also established a reserve.

The battle began with the Dehli horsemen making a charge against Timur’s center and left flank. The attacking cavalry nearly cut through to the nomads’ second line, but timely deployment of Tatar reserves repulsed their charge.

As the Indian cavalry retreated, Mahmud committed his elephants. This was the moment for which Timur had been waiting. Upon his command, his troops lit the flammable materials tied to the backs of the camels and buffalos. The terrified animals, baying in pain and prodded by Tatar spears, advanced toward the elephants. Frightened by the wall of living torches, the elephants panicked and ran away in helter-skelter fashion. They trampled a large number of their own infantry as they fled the field.

Taking advantage of the chaos, Tatar archers swept around them. They fired up at the elephants’ platforms, picking off elephant riders by using their composite bows with great precision. The victorious Tatar troops then chased the fleeing Indian army back to the gates of the city; however, they turned away in time to avoid fire from the enemy’s missile weapons deployed on the high battlements.

Mahmud fled the city during the night with the remnants of his army. Timur took possession of Delhi the following day without a fight. A week-long orgy of slaughter followed; the Tatars burned the beautiful city to the ground. After spending two more months mopping up resistance, Timur’s army returned to Samarkand. It brought with it enormous troves of treasure. Timur had no intention of establishing his rule in India; he had simply wanted to devastate and plunder it. After his departure, Mahmud slunk back to his devastated capital. He had an arduous task before him, given that his sultanate was in a state of chaos and anarchy.

Returning from India in 1399, Timur did not have time to rest. His oldest son, Miran-Shah, ruled Persia as Timur’s viceroy. A fall from a horse caused him brain damage, and Miran-Shah became a shadow of his former self. Taking advantage of Miran-Shah’s disability, Timur’s enemies raided his domain and fomented unrest. Hurrying to Miran-Shah’s stronghold at Soltaniyeh in northwest Persia, Timur relieved his son of his duties and took personal control of his territory.

Timur crushed troublesome neighbors Kara Yusuf of the Kara-Koyunlu Turcoman kingdom and his ally Sultan Ahmed Jalayir in Baghdad. They fled west to take refuge first in Syria under Egyptian Mamluk Sultan Nasir-ad-Din Faraj, and when Syria fell they sought safe haven with Ottoman Sultan Bayazid I.

In his march to Syria, Timur casually snapped up several small territories belonging to the Ottoman Sultan. The two rulers exchanged threats in correspondence, which inevitably led to open war between the Ottomans and Tatars. Timur spent two years ravaging Syria. In 1400, he sacked and destroyed Damascus and then turned his attention to Aleppo. During the sack of Aleppo, the Tatars fashioned 20,000 severed heads into pyramids.

Timur advanced into Ottoman Anatolia in late spring 1402. His march into central Anatolia showed all the hallmarks of his customary brutality. In the border town of Sivas, Timur ordered the execution of a garrison commanded by Sultan Bayazid’s eldest son. In the ensuring massacre, the Tatars buried alive 3,000 Christian Armenian soldiers.

At the time of Timur’s offensive, Sultan Bayazid I was besieging Constantinople, the last remnant of the once-great Byzantine Empire. He raised the siege and rushed east to meet Timur. The forced march of his Ottoman army in the scorching summer heat took a heavy toll on his troops.

In a daring maneuver executed with great skill and coordination, Timur swung southwest undetected by Ottoman scouts and came up behind Bayazid, cutting off his avenue of retreat. The two armies squared off on the Cubuk Plain near Ankara on July 20. Timur fielded 140,000 troops, mostly mounted. He also brought with him 32 war elephants. He took up a position with the center of his army, leaving the flanks to his sons Miran Shah and Shah Rukh.

Bayazid’s army was roughly half the size of Timur’s army. The Ottoman army consisted of regular Sipahi cavalry, janissaries, and irregulars. The Ottoman sultan also had an auxiliary force of 5,000 warriors led by Serbian Prince Stefan Lazarevic. This auxiliary unit was composed of Serbs, Albanians, and Wallachians.

Many of the Ottoman troops were Anatolian provincial levies. Men of dubious loyalty, many of whom were recently conquered Turcoman warriors, commanded these levies. Because of the dubious caliber and condition of many the Ottoman troops, Bayezid’s lieutenants urged him to fight a defensive battle, but Bayezid had other plans.

The sultan deployed his forces on the Cubuk Plain with his back to the hills. The European vassals under Prince Stefan deployed on the right, and Anatolian troops and Turcomans took up positions on the left. Bayazid personally commanded the center with his regular troops. Five of Bayazid’s sons were with him. The most distinguished of these, Suleyman and Mehmed, led the left wing and rearguard, respectively. The Ottomans army’s strength lay in its center, while the Tatars’ strength lay in their flanks.

The battle began when thousands of Timur’s horse archers unleashed a storm of arrows that rained down on the Ottoman ranks. The Anatolians and the Turcomans quickly deserted and went to Timur’s side. As the battle progressed, the sheer weight of the superior Tatar numbers began to take its toll. The Tatar flanks began to wrap around the Ottoman army, threatening to encircle it.

In the process, the Serbs found themselves cut off; nevertheless, they fought their way to Bayazid’s position. The majority of Serbian knights wore heavy plate armor, and therefore the Tatar arrows bounced off them, causing little damage. The proud Serbs fought like lions, thus earning Timur’s begrudging praise. Surrounded on a small hillock, Bayazid rejected Prince Stefan’s suggestion that they retreat together. Instead, he entrusted Suleyman and his treasure to Stefan’s care. The Serbs succeeded in cutting their way out. Meanwhile, the ring closed around Bayezid, who was soon captured. The only Ottoman sultan ever to be taken prisoner, Bayazid I died three months later in captivity.

The Ottoman defeat reverberated through Europe. While the captured Ottoman sultan’s sons engaged in a civil war, the Byzantines received a temporary reprieve. In the manner of “the enemy of my enemy is my friend,” the kings of Western Europe rushed to congratulate Timur and establish diplomatic relations with him.

After defeating Bayazid, Timur continued a triumphant march across the length of Anatolia, reaching the Aegean Sea. On December 2, 1402, Timur arrived at the city of Smyrna, the last Christian outpost in the Holy Land. The town’s population was split between Christians and Muslims. The Knights Hospitaller held a strong castle in the city’s small harbor. The castle, which was defended by 200 knights and their sergeants, was situated on a narrow strip of land, with a ditch separating the castle from the mainland.

After an initial assault on the castle was beaten back, Timur settled in for a proper siege. Under fire from the defenders, who employed naptha and Greek fire, the ditch was steadily filled. Meanwhile, Timur’s stone-throwing artillery battered the walls for two weeks. The Tatars eventually breached the walls and stormed into the castle. The surviving knights cut their way through the swarming mass of Tatars to the harbor, where they escaped by sea. Afterwards, the Tatars massacred the Christians in Smyrna and destroyed the crusaders’ quarters in the Aegean coastal city.

Upon his return to Samarkand, Timur began planning a campaign against China’s Ming Dynasty. He held an impressive feast for his extended family in Samarkand before the start of the campaign. During the banquet, five of his grandsons were married. Timur ordered all religious constraints waived during the feast. Although outwardly professing religious piety, Timur loved alcohol and women. It would be his last feast in Samarkand, and it was worthy of an event hosted by Roman Emperor Caligula.

Timur typically began his campaigns in the spring, but this time he chose to start late in the year. He knew that he was not far from death. With that mindset, he marched hurriedly against China in the hope of conquering it and adding it to his already vast empire. Although still robust for a 72-year-old man, his health had begun to fail him. During this period, he was frequently unable to ride a horse.

His army marched east through deep snow in January 1405. During the arduous winter march, many of his men and their horses froze to death. With a merciless wind whipping through the steppes, Timur caught a cold. He hung on until the army reached Otrar in modern Kazakhstan, where he made his final dispositions before dying on February 18. Timur’s death brought an abrupt end to his campaign against China.

Timur’s son and heir-apparent, Jahangir, had died of illness in 1376. Timur’s grandson Muhammad Sultan, who was the next in succession, fell in battle in 1403. On his deathbed, Timur appointed another grandson, Pir Muhammad, as his successor. Other progeny received governorships of various Timurid provinces. But civil war ensued among rival emirs. Timur’s youngest son, Shah Rukh, eventually succeeded in quelling the warring factions and ascended to the Timurid throne in 1405. He ruled the Timurid Empire until 1447.

The empire that Timur had cobbled together began to disintegrate upon his death, for it lacked the administrative structure possessed by Genghis Khan’s empire. Although he had excelled at waging war, Timur lacked the political foresight to effectively administer the wide territories under his control. While Genghis Khan meted out death and destruction with detached pragmatism, Timur’s violence was of a far more personal, malicious nature.

Timur’s land of birth, Uzbekistan, gained independence following the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. The Uzbeks rehabilitated Timur’s legacy as part of their effort to elevate their national identity and revive past glories. The Uzbeks focused on Timur’s political, economic, and cultural achievements, which had brought unity and prosperity to their land.

In his youth Timur suffered an occasional defeat, but during his march of conquest he absorbed the thrones of 27 kings and sultans in an uninterrupted succession of victories. This achievement justifies his ranking as one of history’s greatest conquerors.