By Victor Kamenir

Russian General Peter Ivanovich Bagration was one of those rare commanders who received near-universal praise from his contemporaries outside of Russia. “Gentle, gracious, chivalrously brave, he was beloved by everyone, and admired by all who witnessed his exploits,” wrote his contemporary British General Sir Robert Wilson. “No officer ever excelled him in the direction of an advance or rear guard.”

Such plaudits are all the more remarkable when one considers that he had to claw his way up through the ranks in the Imperial Russian Army. Bagration was just one year old when his father, Prince Ivan Bagration, a descendent from an impoverished branch of the royal Georgian Bagrationi dynasty, immigrated with his family to Russia in 1766. Since his princely rank was not recognized by the Russian government, Ivan rose no higher than second-major during his service in the garrison at Kizlyar fortress in the northern Caucasus.

In Russian society, someone of Peter’s lineage would commonly have been educated by private tutors and possibly in the cadet corps in the capital; however, the financially challenged family was not able to provide young Peter with top-notch schooling. Thus, the younger Bagration was educated at the garrison’s school along with other officers’ children. At the age of 17, he enlisted as a gentleman ranker, an enlisted soldier with some claim to privilege, in the Astrakhan Infantry Regiment in 1782.

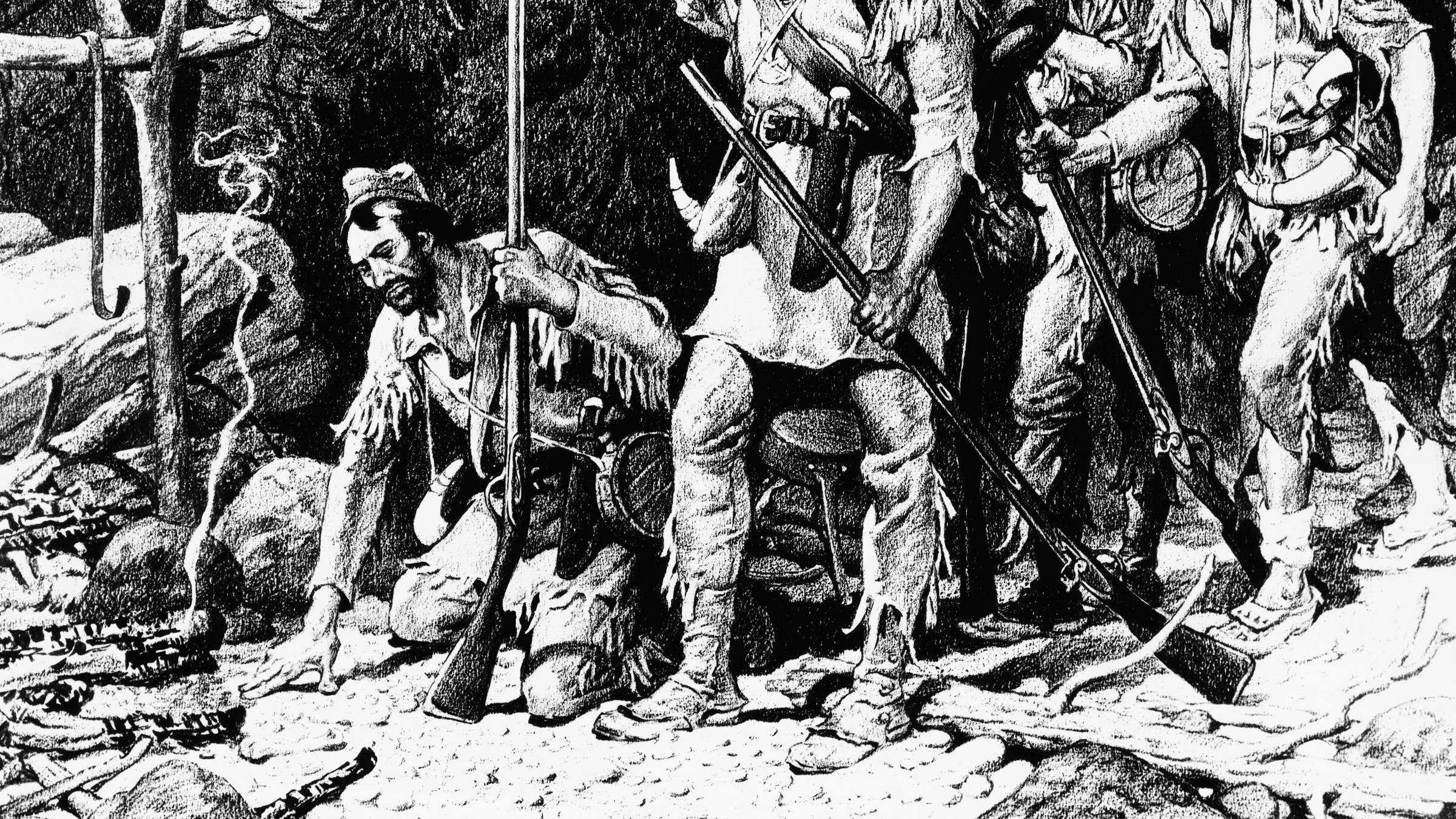

Service in his home area on the northern frontier of the Caucasus region involved constant guerilla warfare against mountain tribesmen who bitterly resisted Russian encroachment. During this time, the younger Bagration gained invaluable combat experience and a earned a promotion to sergeant. While campaigning in the region in 1785, Bagration’s regiment suffered such heavy casualties that the surviving soldiers were absorbed into the Kavkazski Infantry Regiment.

In the ranks of the Kavkazski regiment, Bagration participated in the Russian siege of the Turkish fortress of Ochakiv on the Black Sea. His superiors noted his bravery, composure under fire, and leadership abilities.

Because of this performance, Bagration was promoted up the chain. By 1790, he was a captain; in 1791, he was promoted to major and transferred to the Kiev Mounted Chasseur regiment.

Bagration’s rise through the ranks continued unabated. He was promoted to lieutenant colonel and given command of a jaeger (ranger) battalion in 1795. Bagration’s temperament, astute nature, and initiative were perfectly suited for the command of these light troops, who were frequently tasked with difficult missions. Three years later, he received a promotion to full colonel.

Great opportunity awaited him in the War of the Second Coalition, which erupted in 1798. Russian Tsar Paul I dispatched an expeditionary corps under preeminent general Count Alexander Suvorov to northern Italy the following year to assist the allied Hapsburgs against the French. While en route to Italy, Bagration received a promotion to major general, for Suvorov had recognized his abilities in earlier campaigns. During the subsequent Italian and Swiss campaign of 1799, Suvorov served as Bagration’s mentor.

The two generals were kindred spirits who both had a fondness for aggressive operations. Even though Bagration was the most junior Russian general in the Russian expeditionary corps, he quickly earned Suvorov’s trust. As a sign of his regard for Bagration, Suvorov assigned him to lead the Allied advance guard.

The Italian campaign was a stunning success for the Russian expeditionary corps. Bagration came to the forefront during the expedition when he captured Brescia. In a string of successful military operations in Italy, Suvorov drove out the Republican French forces.

Unfortunately for the Allies, French General Andre Massena soundly defeated an Austro-Russian army at Zurich in September 1799 led by Russian General Alexander Korsakov. In the wake of the defeat, the Austrians concluded a separate peace with France.

Suvorov received orders to march to Zurich to try to save the situation. He then undertook a grueling trek through the St. Gotthard Pass in the snow-capped Alps to central Switzerland. Bagration once again led the advance guard under conditions that required a superhuman effort by everyone in the army. After reaching central Switzerland, Suvorov led his army on a strategic withdrawal to Russia. During the retreat, Bagration was given command of the rearguard. Suvorov’s protégé again distinguished himself when his 6,000 troops fought off a French army five times its size at Hollabrunn in Lower Austria.

Upon returning to Russia, Bagration’s exploits in Italy earned him a prestigious assignment as the commander of the Life-Guard Jaeger Battalion. Being in the emperor’s favor, Bagration was frequently invited to the most fashionable salons of St. Peterburg. Emperor Paul conferred upon Bagration the title of prince in 1800, which gave the Bagration family a firm footing in the Russian nobility.

The long series of wars against Napoleon continued under the new emperor Alexander I, son of Paul I. Bagration fought in every major battle from 1805 to 1807, including Austerlitz, Eylau, Heilsberg, and Friedland.

Just two weeks before Austerlitz, Bagration led Russian troops in a rearguard action at Schongrabern in Lower Austria, thus allowing the main Russian army time to retreat and link up with reinforcements. Despite being given up for dead, Bagration was able to break contact with the enemy and rejoin the army. Bagration received a promotion to lieutenant general in 1805. He showed extraordinary courage while leading the advance guard at Friedland in 1807, where he very nearly overwhelmed the French right in the first phase of the battle. Not long afterwards, his soldiers, who worshipped him, dubbed him “Eagle of the Army.”

During a lull in the Napoleonic Wars, Bagration turned in a stunning performance during the Finnish War with Sweden in spring 1809 when his 17,000 troops captured the Aaland Islands in a march over the frozen ice of the Gulf of Bothnia.

Bagration assumed command of the Army of Moldavia later that year when it devolved to him following the death of Field Marshal Alexander Prozorovski. Operations along the Danube River against the Turks were largely centered around fortresses located on both sides of the river. The opposing armies crossed and re-crossed the Danube, withdrawing to their sides at the end of each campaign season. Initially, Bagration’s operations against Turkish positions on the right bank of the river went well, winning a battle and capturing two fortresses. As a result, he was promoted to general of infantry, which equated to full general.

At the end of the 1809 campaign season, due to political necessity, Alexander demanded that Bagration keep the army on the right bank of the Danube River to maintain possession of hard-won territory. Bagration was well aware that a lack of supplies and insufficient lodgings during the winter would cost him half of his army.

He chose to save the army over his career. He disobeyed Alexander and returned his army to the left bank of the river, leaving behind only a token force. The move earned him the enduring enmity of Alexander; the tsar relieved him of his command in March 1810 and transferred him to an insignificant post in the Ukraine.

His fortunes changed again when he received command of one of several Russian western-front armies when Napoleon invaded Russia on June 24, 1812. Tsar Alexander had three armies positioned against Napoleon. The Russian right flank was held by General Michael Barclay de Tolly’s 127,000-strong First West Army, the center by Bagration’s Second West Army of 48,000 troops, and the left flank by General Alexander Tormasov’s 45,000-strong Third West Army south of the Pripet Marshes.

The Russian armies fell back in the face of Napoleon’s Grande Armée, which contained 400,000 French soldiers and 285,000 allied troops. Although Barclay and Bagration tried to maintain communications with each other, they found it difficult to do so in the face of the rapidly advancing French army. Delays in communications spawned misunderstandings and misjudgments; as a result, the relationship between the two generals soured.

The two Russian armies united on July 22 at Smolensk. Tsar Alexander, who accompanied Barclay’s army, verbally appointed Barclay to overall command before he departed for safer environs. But without written confirmation of his order, Bagration proceeded as if he were co-commander of the combined army rather than Barclay’s subordinate.

After bitter rearguard action at Smolensk followed by a retreat eastward, the smoldering enmity between Barclay and Bagration came to a head. Many senior positions in the Russian military were occupied by ethnic Germans, French royalist émigrés, and other foreign-born officers. Russian officers, including Bagration, tended to resent the preferential treatment shown in the past by the Russian court to ethnic Germans who hailed from Russia’s Baltic territories. Despite his Georgian roots, Bagration considered himself Russian. He took it upon himself to accuse Barclay of treason. It was an unjust accusation at best.

Unknown to Barclay and Bagration, the tsar had appointed General Mikhail Kutuzov, a popular ethnic-Russian officer, as commander-in-chief of the combined army shortly before the battle at Smolensk. Kutuzov arrived in the field to take command of the army on August 17. Russian officers and soldiers received Kutusov’s appointment with great enthusiasm. To the consternation of Kutusov and his allies in the army, however, Bagration resented Kutusov’s appointment.

Kutusov issued orders for a continued retreat and the continued use of scorched-earth tactics. It was both militarily and politically unrealistic to draw Napoleon all the way to Moscow without offering battle, though. Kutuzov decided to make a stand at the village of Borodino, 80 miles west of Moscow. He deployed Barclay’s army to cover the right and center of the Russian position and Bagration’s army to hold the left. Bagration’s troops were more exposed because the left flank lacked terrain obstacles. For that reason, Bagration ordered his men to construct several arrow-shaped earthen fieldworks that became known as Bagration fleches to strengthen their portion of the line.

Napoleon attacked on August 24. He sought to pin down Barclay’s troops while he launched a sledgehammer attack against Bagration’s left wing. The fleches changed hands many times during the course of the savage fighting.

Bagration was struck by a shell fragment in the left leg that unsaddled him. Believing the wound to be a minor one, the stout-hearted general refused to go to the rear. Only after he began losing a great deal of blood did he allow his staff to remove him from the battlefield. Medical staff at a field hospital removed a piece of broken tibia from the wound during his initial examination; however, they failed to thoroughly clean the injury.

After 12 hours of savage fighting, Kutuzov ordered his army to retreat during the night. In so doing, he abandoned Moscow to the enemy. Bagration was initially taken to Moscow, a decision he did not approve. “I will die not from the wound, but from [being in] Moscow!” he exclaimed.

At his request, he was taken further east. He eventually arrived on September 19 at the village of Sima, where he convalesced at the Golitzyn estate, which was situated northeast of Moscow. Neither Bagration nor his doctors appreciated the severity of his wounds. Medical personnel missed a window of opportunity when surgery might have altered the situation.

Bagration’s leg became severely swollen and painful, and he came down with a raging fever. Exploratory surgery performed two days later showed extensive damage to the bone, tissue, and blood vessels. Gangrene set in, and he died on September 24. He was initially interred in a church cemetery in the village. Tsar Alexander, who still bore a grudge against Bagration, refused to allow him to be buried in Moscow.

Bagration’s remains were transferred in July 1839 from Sima to Borodino during the reign of Tsar Nicholas I. But communist officials ordered the destruction of both the monument and Bagration’s grave at Borodino in 1932. Local residents collected and saved his bones.

On the eve of the 175th anniversary of the battle in 1987, his remains were re-interred once again at Borodino. Bagration’s body lies at the site of the Great Redoubt. To this day, his indomitable spirit lives on in Russia through his legacy of bravery, tenacity, and grace under fire.