By William G. Dennis

In Eisenhower’s Lieutenants, eminent historian Stanley Weintraub wrote that communications in the 1800s between America’s scattered frontier garrisons were slow, which encouraged a tradition of individual initiative in the American army. This tradition served America well in the fast-moving battles of World War II. He also wrote that the U.S. Army in World War II was the most mobile army in history. The U.S. built 800,000 2.5-ton trucks alone, as well as impressive numbers of other models. But to enhance that mobility America created lightly armed divisions that did not have the firepower to do well in grueling positional battles.

The defeat of the German forces in Brittany is a good place to examine Dr. Weintraub’s arguments. When the Allies gained entry into Brittany after the Normandy invasion by capturing bridges at Avranches, the battle shifted from bludgeoning the way through hedgerows to moving quickly to exploit the disarray of the scattered German forces. It ended with a campaign to capture the fortress city of Brest that involved some of the heaviest fighting that had yet taken place in the European theater.

The remarkable speed of the American advance outran communications and forced the leaders of detached forces to use initiative to take advantage of fleeting opportunities. Fortunately, they were prepared to do so by training and tradition. The battle against the strong defenses of Brest, which were manned by a heavily armed garrison about the size of the attacking forces, was a grueling fight that needed considerable firepower to win.

The Brittany campaign did not unfold as the Allies expected. Had the Germans acted rationally, the battle for France would have been a long series of Allied attacks to drive back the German infantry while fending off counterattacks by Germany’s mobile forces. The expectation was that the Germans would retreat as needed while inflicting as many casualties as possible on the Allies.

But Hitler’s lack of understanding of mobile warfare and his growing distrust of his generals produced a very different battle. His insistence on never giving up ground meant that the German mobile forces that arrived early in the battle for Normandy were squandered attempting to hold defensive positions. The front became so brittle that there was no way to seal off the Operation Cobra breakthrough.

The plan the Allies developed before D-Day was based on the assumption that, as the battle moved north toward Germany, the Germans would deny the Allies the use of the ports in northern France and Belgium as long as they could. So the U.S. needed to be able to bring huge quantities of supplies ashore in Brittany. The Germans were expected to destroy the existing port facilities so any tonnage that could be put through the captured ports would be a bonus. Most of the supplies would come through an artificial harbor, similar to the Normandy Mulberries, to be constructed in Quiberon Bay.

To keep German garrisons in nearby cities from firing on naval conveys, the U.S. needed to capture Rennes, Brittany’s main communications center, cut across the base of the Brittany peninsula to Quiberon, capture that port, and the ports of Brest, Lorient, and St. Nazaire on the south coast of the peninsula.

Hitler had declared the coastal cities were to be “fortresses” and garrisoned (usually with second-class troops) to deny the Allies the use of those ports for as long as possible. This cost the Germans between 180,000 and 280,000 men; historians are divided about the wisdom of the decision. By the time of the breakout, the Germans had largely denuded the peninsula of the better units there and the Allies hoped that the ports would fall after brief, token defenses.

Instead of the coherent defense the planners had expected before the Normandy invasion, what was left of the German forces in the interior of Brittany were small garrisons that were trying to gather in German-controlled areas.

The shattering German defeat at Falaise in August 1944 turned Allied attention to the north; coincidentally, the attack on Brest began the same day as the Allied troops pursuing the Germans crossed the Seine. When the decision was made to attack that city, the Allies were only beginning to realize that their plans for Brittany needed to be adjusted to take advantage of the enormous opportunities the German collapse in Normandy presented.

The Brittany campaign was in the hands of two commanders with wildly contrasting styles: the brilliant, flamboyant Third Army commander Lt. Gen. George S. Patton, Jr., and Maj. Gen. Troy Middleton, who commanded VIII Corps. Middleton was a steady and methodical planner, while Patton was renowned as a hard-charging, hell-bent-for-leather leader.

Third Army headquarters estimated that the divisional artillery of two divisions, augmented by 10 battalions of artillery assigned to Middleton’s corps —a total of 18 battalions—would provide adequate support for the attackers.

In fact, the area defended by the Germans was so large that it took three divisions, supported by an additional eighteen battalions of artillery, plus 4.2-inch mortars whose round had the same explosive power as a 105mm artillery shell, and the fire of tank destroyer battalions acting as artillery—a total of thirty-four battalions—to envelope the Germans positions. In addition, as was normal in the European theater, Middleton’s forces were not significantly more numerous than the defenders.

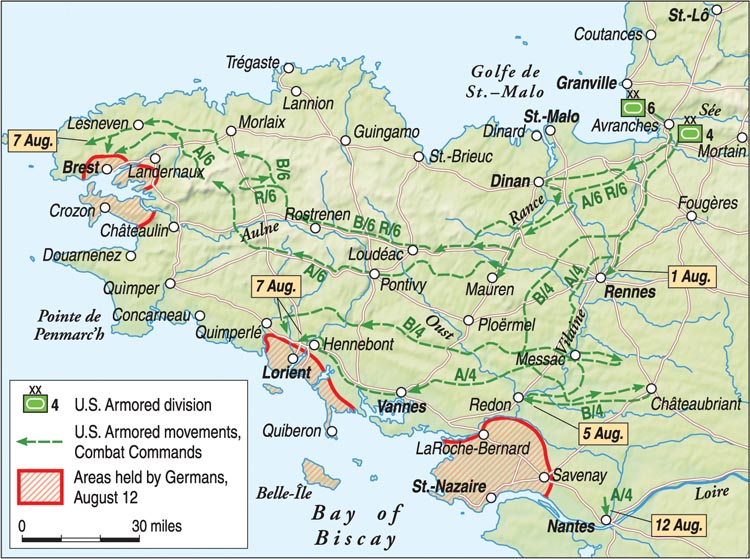

Allied plans changed several times but Patton settled on having the 4th Armored Division capturing Rennes and Nantes, then moving west to capture Vannes and screen the German positions around St. Nazaire and Lorient. The 6th Armored Division, under Maj. Gen. Robert W. Grow, was tasked with moving through the interior of the peninsula to test the defenses of Brest and, hopefully, capture it.

Task Force A moved out ahead of the main body of the 6th Armored. It consisted of tank destroyer brigade headquarters that controlled the following units: a group of armored cavalry and another group of tank destroyers. (The term “tank destroyer” as used here referred to a lightly armored tracked vehicle carrying a high velocity cannon in an open turret.) “Groups,” as the term was used by the Army at the time, consisted of two battalion-sized units and a headquarters. Task Force A also included a battalion of engineers and a separate pontoon bridge company. The task force, whose mission was to prevent the Germans from blowing bridges and to secure the railroad line to Brest, was later augmented with a battalion of infantry.

There were already Allied covert operations troops operating in Brittany with approximately 20,000 armed French Forces of the Interior (FFI). They were attacking small parties of Germans, preventing German sabotage, and providing intelligence to Allied forces. Task Force A made contact with them on August 6 and found that they had largely cleared the Germans out of the interior of the peninsula.

They directed Task Force A around remaining German concentrations and guarded the captured bridges and other targets. With their help, the task force’s mission was successful and the railroad and highways stayed open. Before it was dissolved, the task force had captured 5,700 prisoners.

As the 6th Armored moved forward, an unexpectedly tough fight was developing for the ports of St. Malo and Dinard to the north at the base of the Brittany peninsula. Patton had told Grow to head directly to Brest as fast as possible. Since Patton gave the order directly to Grow, Middleton knew nothing of it. Nor did he know that the division’s forward elements were well past the ports. Middleton ordered it to halt in place in anticipation that the division would be needed to help reduce those ports.

When Patton learned of Middleton’s instruction, he controlled his famous temper and got the 6th on the road again. Combat Command A moved west parallel the north coast and Combat Command B and later Combat Command Reserve moved down the center of the peninsula. In addition to Task Force A, Middleton strengthened the division with another battalion of tank destroyers, a battalion of self-propelled 155s, and a battalion of antiaircraft artillery.

Middleton complained that his armored divisions had moved so far and fast that he had no idea of where they were. This was a constant problem for both sides during this phase of the campaign. Neither sides’ signal equipment was up to handling the distances involved and volume of traffic, although the communications personnel mitigated the problem by successfully putting telephone lines the Germans had strung back into operation.

The 6th Armored’s tanks entry to Leseneven signaled the 266th Volksgrenadier Division that the time had come for the Germans to destroy the 280mm guns at Paimpol and withdraw to Brest. The German Seventh Army headquarters could not believe that the American unit had moved so fast, and the 266th was ordered to return to its positions on the north coast of Brittany.

Initially, the Americans seriously underestimated German strength in Brittany. Patton told Middleton that there were only 1,000 Germans between St. Malo and Brest; the 6th Armored captured 10,000. When the 6th reached Brest, Grow ordered Combat Command B to test the defenses. The attack drove in some outposts but was stopped. It was clear that a substantial force of infantry, supported by much artillery, would be needed for a successful assault.

While the 6th was waiting for infantry, parties of German troops began harassing the division trains and sniping at division artillery. Their commander was captured while moving ahead of his main body and the attackers were identified as the same 266th VG that had tried to move earlier. Because of Seventh Army interference, it was only now attempting to reach Brest. Only about a thousand troops made it to the city.

Meanwhile, Maj. Gen. John S. Wood’s 4th Armored Division reached Rennes on August 1. As a transportation hub, the city was just as important to the Germans as it was to the Allies and small German detachments were drawn to it. The garrison was large enough to beat off a probe by the 4th’s spearhead and another attack later in the day. Wood needed time to get an additional infantry regiment from Middleton to supplement the limited infantry component of his division for the street fighting he saw coming.

Wood had the city encircled when the 13th Infantry Regiment of the 8th Infantry Division arrived on August 2. On the 3rd, they penetrated the city and that night the remains of the garrison successfully exfiltrated to the south, eventually reaching the German-controlled fortress city of St. Nazaire.

There was a delay before Wood’s CCA headed south for its next assignment. Once resupplied, CCA seized the port of Nantes closing off the lower Loire River crossings and completed the capture of Vannes that the FFI had already begun.

It was soon joined by the rest of CCB, which had seized the crossroads towns of Redon and Châteaubriand. Near Lorient it had mistakenly bivouacked in an open field well within the range of the German guns defending the city and only 800 yards from a German observer with a clear view of the bivouac. The barrage the Germans subjected them to caused more casualties than any other encounter since they had landed.

Because the Allies belatedly realized that the real fight had become the advance into Germany, they never attacked the cities of Lorient and St. Nazaire, which remained in German hands until the end of the war.

Task Force A passed through Avranches on August 1 and the 6th Armored’s probing attack on Brest took place on August 7. Brest lies 200 miles west of the starting point of the campaign; in between there were ambushes to avoid by countermarching, detouring, and skirmishing with isolated parties of Germans.

It was an exhausting campaign. In one headquarters, several officers fell asleep during a conference. By tracing the paths of units on maps of the campaign, it appears that some units advanced well over 200 miles by the time Brest was invested. It was a splendid performance that fully demonstrated the mobility of the American Army and the quality of the units that had been built for this war.

Maj. Gen. Robert W. Grow, the 6th Armored’s commander, was rightly proud, even elated, by the performance of his division. He had “received a cavalryman’s mission from a cavalryman [Patton].” It was the kind of campaign they had trained for and been denied in Normandy.

His division was independent of higher command in its advance from Avranches to Brest, taking advantage of the American tradition of individual initiative that allowed units to improvise when the unexpected occurred and direction from higher headquarters was lacking. Its move was the most extended operation of any single division in the war. Its success was measured by the fact that by the second week in August single travelers could travel the length of the Brittany peninsula in safety. Only the spectacular victory further north at Falaise obscured the achievement. Dr. Weintraub’s assertion that the U.S. Army had become the most mobile in history was clearly correct.

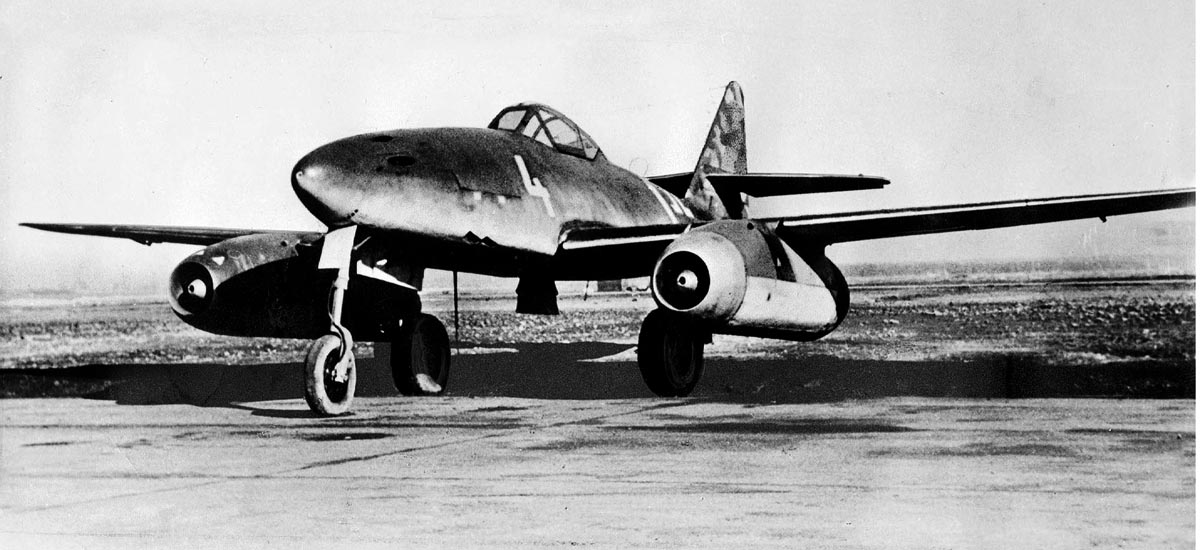

The campaign also illustrated how the American Army had mastered what later became known as the air/land battle. In the Germany army in 1940 a request to the Luftwaffe for air support had to come from an army headquarters. In 1944 American captains were calling for strikes, often conducted by airplanes that were overhead, waiting for the call.

The first phase of the campaign to conquer Brittany ended when Middleton relieved the 6th Armored and General Omar Bradley ordered three infantry divisions into the battle for Brest: the 2nd Infantry Division deployed on the left, the 8th in the center, and the 29th on the right flank.

The Opponents

The armies that faced each other in this battle had been developing in very different ways during the last few years. The 2nd Division, commanded by Maj. Gen. Walter M. Robertson, was a regular army division, formed during WWI, that continued on active duty between the wars. It was substantially understrength until its ranks were filled out with draftees.

The 8th, commanded by Maj. Gen. Donald A. Stroh, was also formed during WWI but was deactivated after it ended. It was reactivated for WWII and, outside of the key leadership cadre, it was made up of almost all draftees. The 29th, commanded by Maj. Gen. Charles Gerhardt, was initially a National Guard division made up mostly of Maryland soldiers. But there had been many transfers before the 29th went into combat on June 6 at Omaha Beach and had heavy casualties since. These had been replaced without regard to where in the U.S. they came from.

The 2nd had also taken heavy casualties in Normandy, but effective commanders knew the importance of integrating replacements into their units. The best procedure was to pull the unit receiving the replacements into reserve before their replacements arrived and give it time to school them in what they would find when they went into combat.

America was able to supply all its divisions with standardized equipment, giving all divisions of a given type of approximately equal firepower. The main difference was that the longer a division served in combat, the more automatic weapons and mortars they tended to accumulate in excess of the tables of organization allowances. They were typical of the divisions America was sending into combat at this stage of the war; they had all been through long periods of training before going into combat.

Surveys and a report compiled by Eisenhower’s headquarters show that the troops felt that their weapons and equipment were, on balance, better than what the Germans used. Granted, there were strong arguments for confining the Sherman to an infantry-support role after the African campaign and deploying a heavier tank earlier in the war.

Infantry companies could have used a more portable machine gun and a larger allowance of them. But as historian Charles McDonald put it, the American Army suffered so much from depression-era neglect that many times the Army had to simply aim for adequacy in choosing equipment.

These divisions were defined more by the very similar training programs they completed after the war began than by their prewar history. As a result, American divisions serving in the European Theater, at this time, were generally interchangeable with other divisions of the same type. The major difference between these three was that the 2nd had an exceptional commander in General Robertson.

America’s personnel policies tended to keep divisions interchangeable. The American training programs for replacements was conducted by a central command and usually lasted considerably longer than German programs. More importantly, American divisions were never so reduced by casualties as to lose their identities. Unlike German corps and army commanders, American commanders could look at their units’ past accomplishments as a reliable indicator of future performance.

There were exceptions. The divisions that were hurried off to Africa 11 months after Pearl Harbor did not have as long to train together as divisions that deployed later, but those deficiencies were corrected by the time they reached Europe. A much higher proportion of American casualties were infantrymen than the planners anticipated so there were never enough trained infantrymen and at times later in the war their training was sketchy. The last few divisions that deployed to Europe had their trained men sent to fill slots in units already in theater and their replacements had no time to train together.

America had few elite infantry units at the beginning of WWII but, in addition to the airborne, the U.S. formed Ranger battalions that were patterned on the British commandos and given especially tough training. They were intended for raids and attacks across especially difficult terrain. But higher commanders often had no clear idea of how to use them, and they were given more mundane assignments like guarding prisoners.

The German Army had moved in an entirely different direction. At the beginning of their rearmament in the 1930s, Germany had attempted to train all their divisions to the same high standard and equip them uniformly—an unattainable goal.

German industry was also unable to supply Germany’s needs. At best, Germany was able to equip its front-line and mobile units with 7.92-caliber Mauser rifles, 9mm pistols and machine pistols, and those units always seemed to have sufficient MG-34 and MG-42 machine guns. For the rest of their divisional equipment, even front-line divisions were forced to use an enormous variety of non-standard and captured equipment.

The elite 6th Parachute Regiment was formed late in the war. It had only 70 trucks for its 3,400 men; there were 50 different models. The weapons and equipment of the second-line “static” divisions were even more diverse and had less organic transport and artillery.

So the weapons and equipment could vary greatly from division to division. At Brest, for example, in addition to the guns assigned to the units in the garrison, Germans manned the guns the French had installed, then they removed guns from sunken warships in Brest harbor and installed a battery of captured Soviet 122mm field guns.

The German manpower situation was similar. Initially, a German infantry division was substantially larger than an American division and the table of organization included anti-aircraft and reconnaissance units. There was also substantially more firepower in the infantry regiments. Mr. Browning’s automatic rifle has its merits but where the U.S. had one in each rifle squad, the Germans had a belt-fed MG-34 or MG-42, and more guns at the company level. There were also normally many more machine pistols than the U.S. Army issued submachine guns.

But in 1943 Germany adopted a new table of organization for its infantry or Volksgrenadier divisions that attempted to produce the same amount of firepower with significantly fewer men. The size of the rifle squads and the rifle companies were reduced and the number of infantry battalions was reduced from nine to six. A fusilier battalion replaced the reconnaissance battalion and usually ended up being used as a seventh infantry battalion.

There were also substantial reductions in the service and support troops. Even more machine pistols were issued to compensate for the reduction in the number of shooters.

German casualties had been heavy and the need for troops was so great that physical standards were reduced and Volk-deutsch—men from Germanic stock from the conquered territories—were drafted. “Volunteers” from non-German countries were encouraged to enlist in Hitler’s anti-Bolshevik crusade.

There were great variations in the quality of the manpower allotted to different types of divisions. This was deliberate. As the successive conscript classes were brought into the army, the best soldiers usually ended up in one of the elite units. Germany still had some elite panzer, panzer-grenadier, and parachute divisions manned with healthy young men. The Allies encountered several of them in Normandy and much of their line infantry was still quite good. But their commanders probably wished that they had spent more of their time training and less time working on fortifications and beach obstacles.

The level of training varied from division to division. Even new infantry divisions that were given long enough to carry out a real training program, such as the 352nd VG Division that appeared at Omaha Beach, fought quite respectably.

Toward the end of the war it was German practice to leave an infantry division in combat until it was so worn down that it was deemed to be “combat ineffective.” Then it was rebuilt. Toward the end of the war, new conscripts were given only four to six weeks of rudimentary training before going into combat.

Beginning in 1943, Germany began fielding another category of infantry divisions that were less capable than the Volksgrenadier units: coastal defense or static divisions. These units lacked a reconnaissance battalion and had less transport and artillery than the field units.

What they did have varied from division to division based on what was available and the length of stretch of coastline they were defending. They were often manned by men who had lost their youthful ability to withstand hardship and/or were less than enthusiastic about serving the Third Reich.

This was especially true of “Ost” battalions manned by volunteers drawn from captured Soviet troops that were transferred from the Eastern Front. The Allies found that the Ost troops would surrender at the first opportunity but, for the rest, it did not take much enthusiasm or youthful vigor to defend a prepared position.

The Battle for Brest

The troops that manned the defenses at Brest followed this pattern. The 353th VG Division that held positions east of Brest was a static division. The 266th VG referred to earlier was also a static division that started without especially good equipment, and must have lost most of it before its disorganized remnants reached Brest.

There were also substantial numbers of Luftwaffe antiaircraft gunners and naval coast artillerymen. Other troops had been guards at various installations or worked at non-combat jobs in depots and headquarters. All told, the Brest garrison was about 40,000 strong.

What made the garrison formidable was the all-volunteer 2nd Parachute Division commanded by Maj. Gen. Hermann-Bernhard Ramcke. At the beginning of the campaign, the garrison commander had been Maj. Gen. Erwin Rauch of the 343rd VG Division.

Ramcke’s troops had been ordered to Normandy but, when the American advance cut him off, Ramcke retreated to Brest and became the garrison commander. He was a fanatical Nazi and almost a caricature of a glory hound. But otherwise he was a good commander and conducted himself with due regard for the rules of land warfare.

He had also trained his division well, using it to stiffen his other units by assigning a few of his men to strongpoints to encourage the other men in the garrison. He also made a persuasive case that every bomb that fell on their positions was one that did not fall on their families at home. The argument and the example of the parachutists helped sustain the morale of the garrison until near the end of the campaign.

The troops were in strongly fortified positions; the Germans had started improving the French fortifications almost as soon as they occupied the city. They began with a belt of fortifications close to the city and naval base to protect them from a raid like the one the British and Canadians had made at Dieppe.

Since the Normandy invasion, the pace of fortification building had speeded up and the emphasis had shifted to building an outer ring of positions designed to give depth to the defense. The inner perimeter consisted of well-dug trenches interspersed with concrete pillboxes and larger blockhouses. There were extensive minefields and barbed wire.

All of this was arrayed in depth so that when a position was under attack, the attackers could often be taken under fire by another. The outer belt of defenses turned almost every village into a strong point with several automatic weapons and at least one anti-tank gun. The Germans made a determined effort to hold the outer belt and to not be forced into the restricted area of the inner belt. This cost them so many casualties that they could have used many more men to adequately man the inner belt.

The geography of the area also had a profound impact on the battle. The countryside close to Brest slopes gently down toward the port. Inland is a plateau with small hills and ridges and there are several hills that are large enough to provide good observation points for artillery spotters. These became crucial ground for defenders and attackers alike. There were hedgerows surrounding many of the fields as in Normandy, but the fields are larger so the hedgerows provide less cover for attackers.

In Normandy, the U.S. Army had learned painful lessons about how to deal with hedgerows that had to be unlearned here. The Rhino tanks and other hedgerow-busting devices were still useful, but the tactics that placed machine guns and tanks in the forefront of the battle were out of place here. Those weapons needed to support the front-line infantry from further back—away from German forward observers and anti-tank weapons.

That otherwise open country was cut by deep ravines that compartmentalized the battle. The Penfield River had cut the deepest channel and separated Brest proper from its suburb, Recouvrance, to the west.

The most striking feature of the area is that Brest harbor is protected by two peninsulas. Across the Elorn River that flows into the harbor to the east of the city is the Daoulas Peninsula that looks across the harbor at the Brest waterfront and the city on the rising slope behind it. The Crozon Peninsula lies further south and extends past the west end of the German perimeter.

Middleton’s first major move was to clear his flanks. He formed Task Force B, consisting of the 2nd Infantry Division’s 38th Infantry, with attachments, to attack down the Daoulas Peninsula. The move deprived the Germans of the ability to fire into the flank of troops moving against the defenses on the west side of the Elorn or counterattack from the peninsula.

The center of the German defenses in the peninsula—and the best observation site—was Hill 154. It was strongly fortified with concrete pillboxes, trenches, barbed wire, and minefields. The defenders were armed with 25 machine guns, anti-tank guns and some mortars.

On August 22, the 38th advanced down the peninsula for several miles until they were stopped by fire from the hill and artillery from across the Elorn. On the 23rd they launched a battalion-sized assault with artillery and tank destroyers firing in support. The Americans kept heavy fire on the hill to keep the Germans pinned down while they enveloped the position.

A German prisoner later remarked that the battalion had used cover and concealment very well, but only part of the hill was captured on the 22nd. That night the Germans tried unsuccessfully to infiltrate men into the space between the two forward companies.

The crisis in the fight came the next day—the Yanks were pinned down by fire from a pillbox. Staff Sgt. Alvin P. Carey was on the flank of the American force leading a heavy machine-gun section and had armed himself with grenades before crawling forward. He killed a German and continued toward the pillbox.

Although wounded, Carey crawled to within grenade-throwing range. After several tries he succeeded in throwing a grenade through an aperture, putting the pillbox out of action. He died before his comrades could reach him but his sacrifice allowed the Americans to move forward and complete the capture of the hill. He was awarded the Medal of Honor, posthumously.

The Americans marveled at the view from the captured hill. They moved the battalion’s 57mm anti-tank guns onto it and used them to provide direct fire in support of the advancing companies.

As they moved down the peninsula, the Germans blew the bridge over the Elorn which had allowed them to shift troops rapidly from one side of the river to the other. By the end of the month, Task Force B had cleared the peninsula and taken 2,700 prisoners.

Middleton was now in position to seriously impede movement in downtown Brest. He moved a corps artillery group to the peninsula and put his own observers on Hill 154 to direct fire into the German rear. To provide security and to place direct fire into those streets, he formed a provisional battalion of 57 machine guns, 12 tank destroyers, and eight 40mm Bofors guns.

On the other flank, Middleton directed Gerhardt to capture German positions west of the city. He formed several small task forces as the main body of the 29th began the attack on Brest. At first, they were two Ranger battalions—the 2nd and 5th—that were attached to the 29th. Platoon and company-sized units captured a number of German positions, usually from much larger garrisons. As the battle unfolded and it became clear that the Germans were much stronger than originally thought, the task forces were reinforced, consolidated, and designated Task Force S.

TF S was initially commanded by the division chief of staff, who was replaced by the assistant commander of the 29th Division, Colonel Leroy “Swede” Watson.

TF S’s ultimate objective was the Le Conquet Peninsula at the tip of Brittany, site of Battery Graf Spee with four 280mm guns. Three of the guns could be rotated to fire on the troops attacking Brest and did considerable damage. Gerhardt was always a difficult man to deal with, and having

11-inch shells falling around his headquarters made him decidedly irascible, especially when it was discovered that the Germans learned its location from a captured field order.

Gerhardt’s response was to give a battery of 155mm guns the task of silencing the

German guns. The 155s were allotted plenty of ammunition and their fire slowed the German cannonade.

An attempt to move into the Le Conquet Peninsula to capture Battery Graf Spee showed that there were just too few Rangers for the job; Gerhardt finally allocated TF S an infantry battalion. On September 6 the combined force, now with plenty of support, moved out. By the 9th, they had broken into the peninsula and the Rangers were left to capture the last few German positions, including the Battery Graf Spee.

The Rangers wanted those positions to surrender and the best way to do that was to locate the German commander and get him to give the surrender order. A four-man patrol under 1st Lt. Robert Edlin approached a German position that turned out to be a pillbox guarding an observation post/fire-control center. It was unguarded and the Germans there were eager to give up. One of them volunteered to take Edlin to the peninsula’s overall commander, a Lt. Col. Fürst.

Taking one of his men with him, Edlin followed the prisoner to battery headquarters and burst into Fürst’s office demanding that he surrender. Even with guns pointed at him, Fürst tried to bluster by pointing out that there were only two Americans in a building full of 800 Germans. Edlin pulled the pin from a grenade and held it to Fürst’s chest. The look in Edlin’s eyes must have been so convincing that he surrendered and that part of the battle for Brest was over.

Meanwhile, by August 25, all was in readiness for the main attack on Brest. All three divisions were in contact with the German outpost line. What seemed a reasonable supply of artillery ammunition was on hand, although not as much as Middleton wanted, and the artillery soon would be supplemented with tank destroyers, air attacks, and fire from naval vessels.

The preparatory fires made little impact and, though well coordinated, the ground attack went nowhere. After more bombing, the attack resumed on the 26th and there was still little progress; it became clear that the garrison was larger than originally thought. Eventually the Yanks realized that there were 75 major German strongpoints and that this would be a tough fight.

Instead of a coordinated move by the three divisions at the direction of the corps headquarters, the divisions and each of their regiments needed to carefully probe and study the German dispositions to find weak spots, then make detailed plans and carefully execute local attacks that overcame German positions one by one. This phase of the battle lasted until September 7 and resulted in piecemeal gains that gradually improved the American position.

The main targets of the divisional attacks were the hills in the outer ring of fortifications that were such good observation points. The first of them to fall was Hill 105 southwest of Guipavas in the 2nd Division sector. Later attacks put the 2nd within reach of Hill 92, the other critical terrain feature in its sector.

When the Germans retired from Hill 105, it gave Stroh’s 8th Infantry Division the opportunity to capture another fortified hill in their sector: Hill 103. It proved to be a tough nut to crack—the Germans had covered it with entrenchments and bunkers. At one point Gerhardt reported, “We are on it, but so are the Jerries.”

The slow progress frustrated Middleton. The attacks would have moved faster had higher headquarters realized the size of the garrison, the number of strongpoints to be overcome, and the challenges facing the attackers.

Dismayed by the lack of progress in the center of his 29th Division sector, Gerhardt elected to shift troops from that area toward the sea. Given the amount and accuracy of the German artillery, the move needed to be made at night although the area had not been reconnoitered. Gerhardt had a lot of respect for his men’s ability. The troops would move west, pivot south, then east. The move succeeded in repositioning his troops, but their attack bogged down in a complex of hedgerows as tall as any in Normandy.

The battle was also slowed by shortages of artillery ammunition. General Eisenhower intervened to raise Middleton’s ammunition and air-support priority. The Services of Supply took advantage of Brest being a coastal city to load ammunition trucks into LSTs and land them on the beaches of Brittany. Ike requested the Ninth Air Force to support the operation with all the aircraft it could effectively use. He also had VIII Corps transferred to Simpson’s Ninth Army which, at that time, had no other combat functions, so its headquarters could work to alleviate supply bottlenecks. By September 7 there was enough ammunition on hand and the local attacks had improved the Allied position sufficiently for the general attack to resume without having to restrict the artillery fires.

On September 8 the general attack resumed with considerably more success. The 2nd Infantry Division took the strongly fortified positions on Hill 92, which opened the way for the 8th Division to move several hundred yards forward toward Hill 82. The 29th finally cleared Hill 103 and took an important strongpoint near Kergonant.

There is no record of how many casualties were inflicted on the Germans during this phase of the fight, but the Americans captured a thousand men for 250 casualties of their own.

The 29th’s capture of Hill 103 did not end the fighting on the hill. The Germans made strenuous efforts to recapture it but the Americans made good use of the German trenches. What broke the back of the German attack was a battalion of 4.2-inch mortars that had been put in direct support of the men on Hill 103. It plastered the attackers with high volumes of highly accurate fire.

Another source of fire support that was extremely valuable was bombing by sections of four—and sometimes eight—P-47s that were usually overhead during daylight hours. When a German strongpoint was located, the commander on the ground could request air support, and it was usually there within 45 minutes. After the target for the airmen was identified, the pilots could usually put their 500- or 1,000-pound bombs on the target.

Once the commanding hills were captured, the battle took a better turn. The troops now had direct observation of all the German-controlled area. The German perimeter had shrunk, allowing the Americans to concentrate their combat power. Perhaps as important, it was now clear that the Germans were losing and their morale began to crack.

While this was going on, eight LSTs and two trains carrying ammunition arrived which removed any ammunition constraints. The next day the 2nd and 8th Divisions entered the old walled city and 2,500 prisoners were taken.

The successes on the 9th gave rise to hopes that the battle was nearly over but, instead, it was moving into its most ugly stage—house-to-house fighting. Fire from well-concealed positions made using the city’s streets suicidal for the infantry and armor alike. Instead, in a preview to what the 1st Infantry Division would experience in “bloody Aachen,” the 2nd conducted what General Robertson called “a corporal’s war.” The troops would blow a hole on the wall on the top floor of a German-occupied house, enter the building, and work downwards behind a shower of grenades and satchel charges. This would continue through the next house to the end of the block.

On many street corners the Germans had built reinforced-concrete dugouts with street-level openings for heavy machine guns. The standard tactic was to detour around behind them, eliminating any resistance encountered in the process until the attackers were close enough for a flamethrower to make the position indefensible. It was a brutal, exhausting fight.

The 2nd had a large area to clear, so the 8th reached the old city wall first. The three divisions were converging on Brest and the field was getting crowded. The Germans still held the Crozon Peninsula so the 8th was pinched out and its sector was divided between the other two divisions along the line of the Penfield River. The 8th relieved a cavalry squadron screening the base of the peninsula and began moving down it.

As the 2nd moved through the streets of town, the 29th was facing a different fight. Their area of operations was less built up but it contained several old French forts, including forts Keranroux and Montbarey.

Keranroux was the target of a battalion of the 175th Infantry Regiment that fought for three days to clear the outer works and approach the fort. The defense began to unravel on the 13th when Staff Sgt.Sherwood Hallman leaped over a hedgerow and wiped out a machine-gun position with grenades and his rifle. After he killed the crew, 12 other Germans nearby surrendered and another 75 followed their example. Hallman received the Medal of Honor.

This opened the way for the whole battalion to move 2,000 yards behind a smoke screen to the fort while it was being bombarded by artillery and aircraft. By the time the 100-man garrison surrendered, the main part of the fort was unrecognizable.

Setter after being captured at Pointe des Capucins on the Crozon Peninsula, September 19, 1944.

Fort Montbarey was also a difficult objective. Its earth-filled masonry wall was 25 feet thick and was surrounded by a 50-foot-wide dry moat. There were about 150 men garrisoning the fort proper and more manning outlying positions who covered a minefield containing 300-pound shells for naval guns equipped with pressure igniters.

Just getting to the fort seemed impossible, but the corps engineer had secured the aid of a British squadron of 15 flame-throwing “crocodile” tanks. The plan was for the tanks to scorch the firing positions on the fort’s outer wall while artillery encouraged the defenders to keep their heads down. Under the cover of a smoke screen, engineers then cleared a path for the attackers through the minefield. After three tanks were put out of action, the bombardment was resumed.

The engineers worked through the night to improve the path through the mines while the crocodiles moved up close to the fort and the artillery hit it hard again. More smoke was placed on the fort and the crocs moved forward, flaming the firing apertures. The flames kept the Germans back while the engineers placed 2,500 pounds of explosives at the base of the wall.

While this was taking place, tank destroyers and the regimental cannon company were brought to within 200 yards of the fort and began firing at its gate. The result was a breached gate and wall. The stunned garrison, including General Rauch, surrendered.

This opened the way into Recouvrance and before the day was done patrols were over its wall. Resistance collapsed. The same day, the 2nd found an unguarded railroad tunnel through the Brest city wall and swept down to the waterfront. The Rangers then captured the remaining forts and the fight for the city was over.

The American casualties were about 6,500; 38,000 Germans were captured. This was the most grueling battle the U.S. Army had yet fought in the European Theater; it would hardly be the last. But in all of them the Army displayed tenacity and an ability to improvise and adapt that helped keep their casualties well below what they could have been.

More important was the impressive support they received from non-divisional units that supplemented the artillery and anti-tank weapons organic to the divisions. Without the tank, tank destroyer, artillery, and air support, much more of the weight of the fighting would have fallen on the infantry and the casualties would have been much heavier. One has only to look at the ruinous German casualties at Stalingrad to see the impact of receiving only the much more modest support available to German infantry.

Dr. Weintraub’s conclusion that American divisions were too lightly armed for grueling battles probably would have been correct had it not been for the impressive kinds and amounts of support they received from these non-divisional supporting units. Still, it was clear that fire support could not win the battle without the valor of men like Sergeants Smith, Carey, and Hallman and Lieutenant Edlin—and the daring and impressive technical skills displayed by the men clearing the minefields and manning the crocodiles at Fort Montbary.