By Kevin Hymel

High over Normandy, France, eight paratroopers of the 82nd Airborne Division charged out the rear door of their C-47 Skytrain aircraft. They whooped and shouted as antiaircraft explosions rattled the plane.

On the heels of the eighth paratrooper came Technical Sergeant Gerald Griffith. He didn’t jump; strapping himself into the seat by the door, he pulled a T-shaped handle, releasing the cargo strapped under the plane’s fuselage. His task complete, Griffith remained seated while the next eight-man group leaped out the door. From his perch, he had a perfect view of the D-Day airborne assault over Ste. Mère Èglise.

Griffith never forgot what he saw: “Some of the paratroopers jumping out of their planes were hit by the prop wash from the plane in front of them, shooting them into the planes behind them, into their propellers.”

These were the opening hours of June 6, 1944, and the C-47s were dropping paratroopers inland from Utah Beach, where American soldiers were expected to land around sunrise—one of the first steps toward liberating France and invading Germany. Griffith had a front-line seat to the action as antiaircraft fire lit up the night with deadly tracers, punching jagged holes in the wings of the C-47.

“It just looked like somebody cut it with a knife,” he recalled, “or like someone hit it with an axe.” He saw other planes take vicious ground fire. “I saw them start down, but I never saw them hit the ground,” he said. The paratroopers had told him earlier that they were glad they didn’t have to ride back in the C-47. “I guess being in a plane made them feel kind of trapped.”

Once the paratroopers had jumped, Griffith’s pilot banked into a wide circle to prevent hitting other planes and flew back to England. “I don’t know how many other planes were coming in behind us, but that was the drill.” With their departure came a feeling of relief. The crew had survived and successfully completed their mission, but the day had just begun. In only a few hours they would soar over France again.

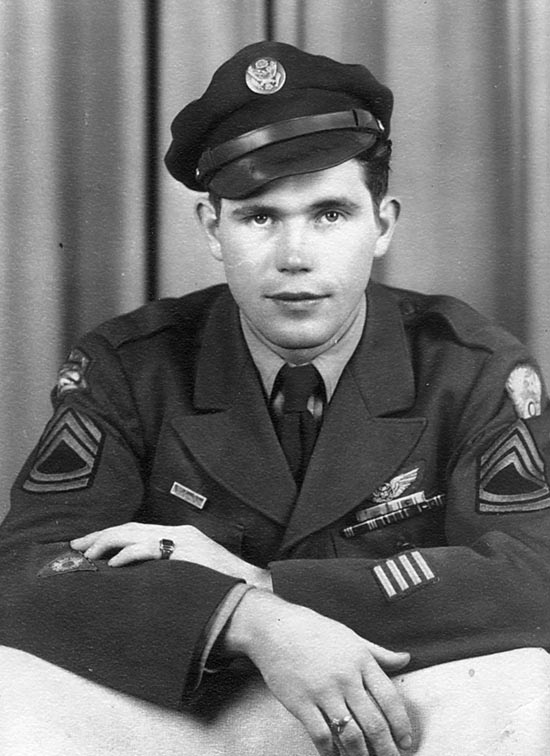

Drafted in April 1943 at the age of 18, Griffith, a native of Centralia, Illinois, trained with the U.S. Army Air Forces in Gulfport, Mississippi, before shipping out to the United Kingdom. He originally served as a top turret machine-gunner on a Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress bomber, where he encountered enemy fire for the first time. “I was a little scared,” he explained. “Flak does not make a lot of noise. You just see pieces flying through the air, and it sounds like hail hitting the airplane. Soon you see holes in your plane.”

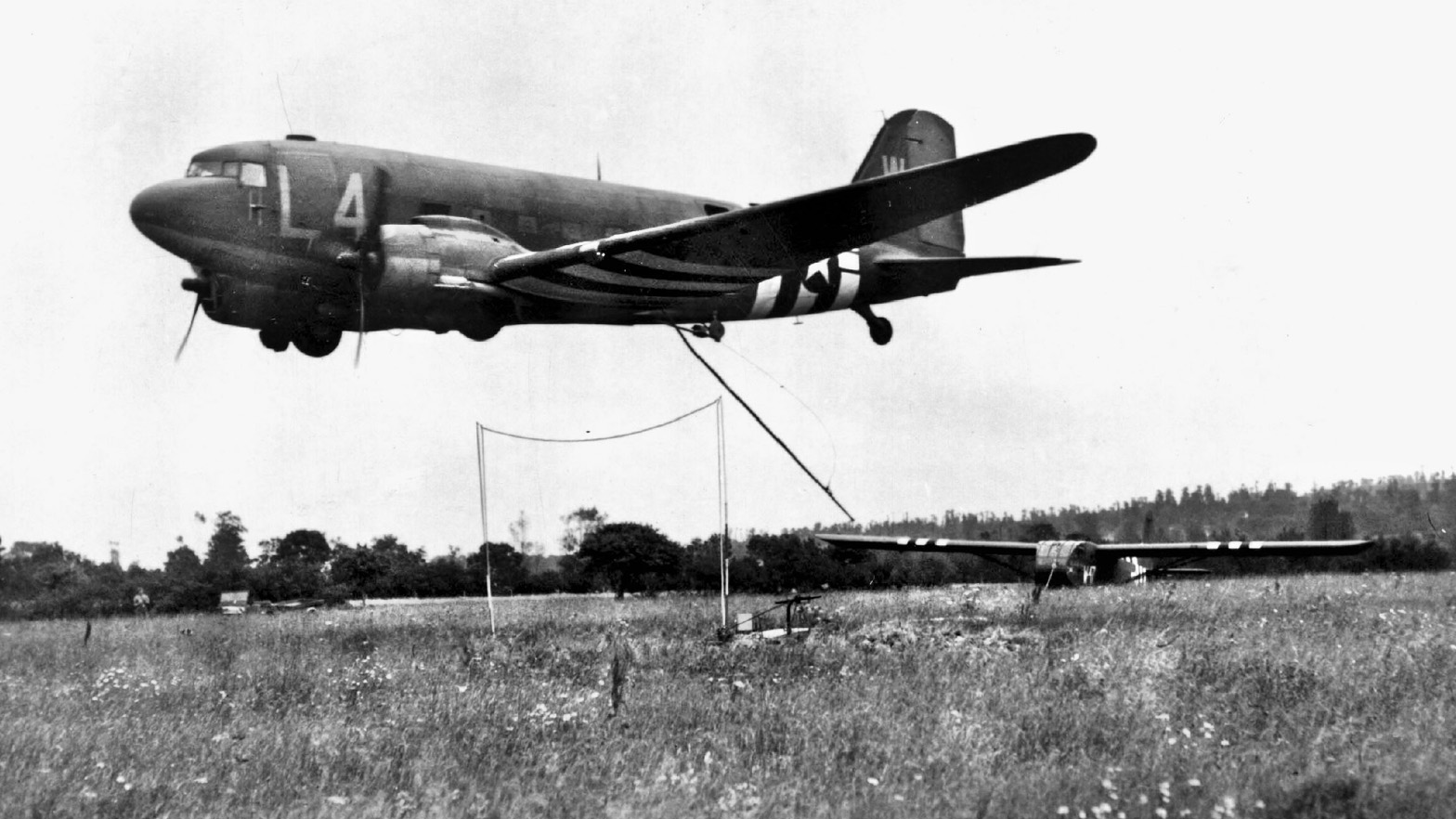

In March 1944, Griffith transferred to the 305th Troop Carrier Squadron, 50th Troop Carrier Wing, 442nd Troop Carrier Group, U.S. Ninth Air Force. As the flight engineer on board a C-47, Griffith sat between the pilot and copilot and worked the plane’s flaps and landing gear. “For two months all we did was practice paratrooper drops and towing gliders for D-Day,” he recalled.

On June 4, Griffith and his crew painted black and white stripes on their wings for easy recognition. D-Day commanders did not want a repeat of the friendly-fire incident over Sicily, in which the Navy and ground troops shot down 23 transport planes, killing more than 100 paratroopers. Then the word came down that the English Channel was socked in with clouds; D-Day was being postponed. “We just figured it was the typical hurry-up-and-wait.” The troops went back to their tents while most crews slept in their planes. The next night, they loaded up the men and took off for France.

The weather had not improved much. Cloud cover scattered plane formations and pathfinders, including specially trained airborne troops who jumped first to mark landing zones for other paratroopers. “Not very many of us dropped our paratroopers where they were supposed to,” confessed Griffith. “There was nothing to show us where to drop our men. My only signal was the red and green lights [inside the plane that told the paratroopers when to jump].”

“My job was pretty simple,” said Griffith. The door was only 20 feet from the cockpit, and the paratroopers’ hookup line served as a handhold for the walk back. He then strapped himself into the seat next to the door. “I had to do this because they might pull me out with them as they went. I wish they did on occasion.”

To give the paratroopers extra firepower once on the ground, large packs filled with guns, ammunition, and other fighting necessities were bolted under the C-47’s fuselage in groups of six and covered with a canvas tarp. These “six-packs” were about eight feet long and two feet wide. When Griffith pulled the lever, he unzipped the canvas, allowing the six-packs to fall. In theory, the six-pack was released between the two lines, or “sticks,” of departing paratroopers. Once on the ground, the first eight paratroopers would walk forward and the following eight would walk back, converging on the six-pack. In combat, unfortunately, the procedure did not work. “I don’t know anyone who ever saw one of those packs,” Griffith remembered.

Griffith’s second D-Day flight was different: daylight provided better unit cohesion, and there was no flak. “We stayed pretty much in formation—loosely.” The sun also brought a spectacular view of the invasion fleet below: “It was pretty much like a bridge of ships, there were so many of them,” recalled Griffith.

Over land, the view changed. “I saw parachutes and equipment lying around and a lot of water where [the Germans] flooded everything.” Griffith’s crew spent the rest of the historic day hauling cargo and dropping it to the men below.

In the weeks that followed, Griffith and his crewmates flew gasoline in and flew out the wounded, eventually supporting the breakout of General George Patton’s Third Army and its drive across France. They hauled five-gallon gas cans to impromptu airports.

Often, German prisoners of war helped unload gas and load the wounded. “They were pretty nice,” reminisced Griffith. “They knew the nicer they were, the more chocolate and cigarettes we would give them.” The wounded were attended to by a flight nurse who did her best to keep the patients stable until they arrived in England. On a few occasions, Griffith saw General Patton. “I just saw him from a distance. He was always running around, and I never spoke to him. We were loading gas and his mind was on business.”

In August, Griffith and his crew flew to Sicily where they picked up more paratroopers for Operation Dragoon, a combat jump into southern France. The mission was relatively calm compared to Normandy, without too much flak over enemy territory. The training and experience were paying off. “There wasn’t much change from earlier operations,” said Griffith. “It was the same thing over and over.”

The flight back, though, was anything but routine. One of the engines coughed out, and the C-47 pilot could not feather the stalled propeller (i.e., turn the blades edge-forward to reduce friction). “The engine kept dragging the plane down,” said Griffith. The pilot managed to a crash landing in the Mediterranean Sea, where it stayed afloat long enough for the men to get out and inflate their life rafts. They ate K-rations and drank fresh water, waiting eight hours until a U.S. Navy ship rescued them and delivered them to North Africa.

“I was always confident we were going to be picked up,” Griffith smiled.

The next big drop came in the Netherlands: Operation Market Garden, British Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery’s ambitious plan to drop three airborne divisions onto vital bridges, securing them and enabling armored troops to cross into Germany. From September 17–20, Griffith’s crew lifted 101st Airborne Division troops and gliders to drop zones around the town of Eindhoven. So many planes took off from England for the operation that witnesses thought the war was almost won. “Everybody had that feeling,” said Griffith.

The first flight was an anxious one. Weighed down with a full load of paratroopers, Griffith’s C-47 also hauled a glider. “The plane was so heavy we kept our flaps down to keep us from falling out of the sky.” The vista, void of flak, was impressive. “You could see planes for a mile in front of you.” Despite the view outside, he spent most of the flight looking at instruments.

“Towing a glider is just like towing a car,” he explained. “It was just a matter of the glider pilot hanging on.” During takeoff, the glider would often lift off before the C-47. When the tow plane reached the drop zone, the glider pilot would tell the tow pilot he was dropping the rope, and then pull a lever above his head. “The rope would stay with us,” Griffith said. “We would fly over a pre-designated spot and drop it.”

Glider landings were rarely smooth. “Very few of them landed intact,” he recalled. “We seldom ever saw those people again.” Once the paratroopers jumped and the glider was released, Griffith felt better as his plane picked up speed and headed back to base. “I really didn’t want any part of the glider after it left the plane.”

The next day, Griffith and his crew towed two more gliders to the drop zone, one containing glider troops, and the other artillery. Weather conditions then worsened over England, preventing reinforcement on the 19th. On September 20, Griffith and his crew dropped their last load of paratroopers.

Reflecting on glider towing, Griffith admitted the bond with the glider crews was not like the one he had with his own crew. In training, C-47 crews lined up on the runway, and officers assigned them a different glider each time. “We seldom hauled the same people twice.” Nor did Griffith associate much with the paratroopers. “We would just watch and make sure they loaded [into] our plane right.” Griffith did feel bad about the men killed on these missions, “but you didn’t spend a lot of time thinking about it.”

Ultimately, Market Garden failed. Weather, poor terrain, destroyed bridges, and surprisingly stiff German resistance prevented Montgomery’s troops from crossing into Germany. Despite fighter protection, the 442nd Troop Carrier Group suffered 23 men killed or missing in action and six wounded. “Operation Market Garden saw our heaviest losses,” lamented Griffith.

In October, the 442nd transferred to Bonnetable, France. During winter months, Griffith and his crew continued evacuating wounded and delivering supplies, but as the weather conditions worsened and the airstrips turned to mud, they moved to St. Andre de l’Eure, outside Paris. “Most local French could speak English, and it was only 50 miles from Paris.” When it came to the GI pastime of bartering, Griffith had an ace up his sleeve: “I didn’t smoke.” Cigarette cartons were worth $100, so he traded them for anything he wanted or thought he needed.

On December 16, the Germans launched their last major offensive in the west—the Battle of the Bulge. Griffith first learned of the attack when he was awakened out of bed by the noise of war. “We heard all this rumbling,” he recalled. “We looked out of our tents and all these [American] tanks went by.” Next, all crews were called to their planes to stand guard against German saboteurs dressed as Americans. German spies had already been captured wearing American uniforms.

But no planes were flying. Fog blanketed the area. Griffith and his crew waited as the Germans pushed west and surrounded the town of Bastogne. General Patton pushed north to Bastogne to relieve the 101st Airborne, which held the town’s vital crossroads.

Finally, the skies cleared above Bastogne on December 24, the day before Christmas. Griffith’s crew flew over the town and dropped supplies, but the Germans greeted them with ground fire. “Some bullets hit one of our engines and we could not remain airborne.” For the second time, Griffith was going down, but this time he and his crew did not know if they would land behind friendly or enemy lines.

Griffith went to the back of the plane and got in the latrine. “It was a safe place to be instead of getting bounced around.” The pilot managed to make a bumpy belly landing in the snow-covered no-man’s-land outside Bastogne and skidded to a halt. The crew only had .45-cal. Colt pistols to defend themselves, and Griffith was wearing low-topped shoes. A handful of soldiers appeared almost immediately in the distance and headed toward them. When they got near, Griffith was relieved to discover they were Americans.

“They took us out of the plane and brought us into town.” During the half-mile hike in the snow, Griffith’s feet became frostbitten. He spent the rest of the siege in a building at the center of town, surviving on C and K rations—a bit different from the mess hall, but he didn’t mind. “I was young, and everything tastes good when you’re hungry.” Christmas passed with no fanfare. The next day, the 4th Armored Division, spearheading Patton’s attack, broke through.

Griffith returned to duty, flying dangerous resupply missions. On a flight back from Germany in early 1945, one of his engines stopped running. The pilot found an emergency runway in Brussels, Belgium, and Griffith fired a red flare from a special tube atop the plane to signal an emergency. But they soon encountered a group of shot-up B-17s also in need of emergency landings. As Griffith’s plane circled, the B-17s landed one after the other, their crews rolling out of the planes as they sped down the runway. “A lot of guys were breaking arms and legs as they spilled out,” explained Griffith. “Then a big ‘boom’ hit us. We thought it was one of our tires getting hit.”

But the ‘boom’ was followed by another, and another. It was not until Griffith landed that he discovered the source of the noise. “They were Buzz Bombs exploding nearby.” Officially called the V-1 pulse jet, German Buzz Bombs earned their name from the loud buzzing noise their engines made while flying to target. “It was one of scariest times in the war for me,” said Griffith.

On March 24, 1945, Griffith participated in Operation Varsity, the airborne assault across the Rhine River—the last natural boundary into Germany. It was also the largest single-day airborne drop into one location, involving 16,000 paratroopers and several thousand aircraft. Griffith’s plane pulled a glider. It was an uneventful mission. “Nothing happened,” he said. “You seldom saw any enemy planes toward the end of the war.” He flew only one mission that day; the Allies had a vast number of planes and had perfected the technique of towing two gliders behind one aircraft, so follow-up missions were unnecessary.

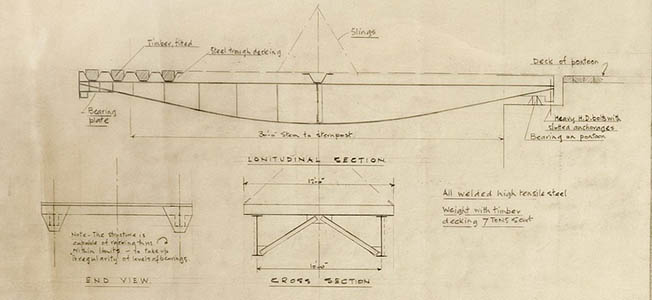

With the last airborne mission a success, Griffith and his crew were given a unique assignment. To expedite the evacuation of wounded from the battlefield, the Army Air Forces had developed a technique of snatching wounded-laden gliders off the ground using low-flying C-47s. With a massive volume of Allied road traffic heading east over the last few bridges across the Rhine and none heading west, this was the Army’s best option for medical evacuation. “It was the first of its kind east of the Rhine,” Griffith explained.

Each glider was loaded with 12 wounded men, a pilot and nurse. The tow rope was laid out in front of the glider and held up between two poles. Then a C-47 swooped in at 150 miles an hour with a special winch that hooked the rope and pulled the glider into the air.

“That was kind of scary,” Griffith admitted. The winch would then gradually tighten up so the glider would not be heavily jerked. “You didn’t really notice it much,” said Griffith. By the time the winch had finished picking up the slack, the glider was already airborne. Nine minutes later, the plane released the glider over a hospital 50 miles behind the front—a trip that would have taken hours on the ground. Ten gliders could transport the same number of patients as 1,500 ambulances. Although the procedure was new, the Army Air Forces had been working on the idea for a long time. “We started practicing it right after D-Day.”

Griffith continued his duties until May 8, the last day of the war. On a supply run into Germany, his pilot got word over the radio of the Nazi surrender. “We were an hour out of Germany,” he recalled. “We just turned around and went back to base.” But Griffith decided to celebrate Germany’s defeat by firing a green flare. “The pilot got mad at me,” Griffith chuckled, “but I figured it was harmless.”

Griffith’s last major undertaking of the war involved delivering Holocaust survivors to Greece—the first leg of a journey to what would soon become the state of Israel. C-47s hauled groups of 30 survivors per trip. “They were nothing but skin and bones,” he recalled. Many of the survivors were sick, and some defecated in the back of the plane.

Even Griffith’s simplest attempts at compassion overwhelmed these suffering people: “There was an 18-year-old girl I took into the cockpit, and I gave her a candy bar,” he recalled. “She ate it down and she threw it right back up.” From May to June, the Army Air Forces transferred 45,525 survivors to Greece. “They were all happy, but not in a talkative mood.”

Griffith went on to serve 30 years in the U.S. Air Force. Looking back on World War II, he confessed that he had nightmares for years after the war. One of his most common nightmares involved a supply mission: “We were hauling gas to Patton, and where we landed, there was a side of a hill filled with dead people. In my dream, there is a German there, trying to shoot me.” He also had nightmares of his C-47 taking off below electric wires, trying not to snag them.

On a cold day in 1982, while playing golf at a local club in Waxahachie, Texas, Griffith complained about his frostbitten feet to his playing partner, Bob Frederick. Griffith then told Frederick about his crash-landing outside Bastogne, and Frederick told him that he was part of a search party that had rescued the crew of a downed plane in that same area. Neither one of them knew for sure if they had met some 38 years before, so they rarely spoke about it to others. “It was something we had between just us.”

Gerald Griffith passed away on December 20, 2017, and was buried in Section 55 of Arlington National Cemetery. Fittingly, his funeral took place on June 6, 2017, the 73rd anniversary of D-Day, Griffith’s baptism of fire.

Kevin M. Hymel is a contract historian for the U.S. Army. He is also the author of Patton’s Photographs: War as He Saw It and a tour guide/historian for Stephen Ambrose Historical Tours, where he leads tours of General George S. Patton’s European battlefields.