By Nathan N. Prefer

The campaign to reduce the importance of the major Japanese base at Rabaul on the island of New Britain—begun more than a year earlier at Guadalcanal and Buna, New Guinea—was finally in its last stages by November 1943, as U.S. Marines fought the Japanese on the island of Bougainville.

In fact, the plan, known as Operation Cartwheel, changed from seizing the enemy base at Rabaul to bypassing it. The seizure of Bougainville in the northern Solomon Islands would complete the base’s isolation.

Major General Roy S. Geiger’s I Marine Amphibious Corps arrived off the Bougainville invasion beaches of Cape Torokina early on the morning of November 1, 1943, and soon began landing Major General Allen H. Turnage’s 3rd Marine Division, reinforced with the 1st Marine Parachute Regiment and 2nd

Marine Raider Regiment. A beachhead was quickly established, and fighting continued as the Marines moved inland. The objective was to establish an airbase on the cape from which air superiority could be maintained over Rabaul, eventually neutralizing the enemy stronghold entirely.

Bougainville is the largest of the Solomon Islands at 125 miles long and 48 miles wide at its widest point. It has a mountainous spine consisting of two mountain ranges, as well as two active volcanoes. The mountains end at the southern part of the island, where the Japanese had built airfields at Buin, Kahili and Kara. The island also has several good harbors, mainly at Buka, Numa Numa, Tenekau and Tonolei. But the Americans chose instead to establish their base at Cape Torokina, where there were no enemy bases, even though the cape was considered a poor anchorage. Their choice completely fooled the Japanese, who believed that the Americans would land on the other side of the island. In 1943, there were no roads on Bougainville—only native trails along the coast and some that led into the mountainous interior.

The Japanese on Bougainville were from Lieutenant General Haruyoshi Hyakutake’s Seventeenth Army and numbered at least 35,000 soldiers and sailors. This force included Lieutenant General Masatane Kanda’s 6th Division, whose previous experiences included the infamous sacking of the Chinese city of Nanking. There was also the 4th South Seas Garrison Force of infantry and artillery. A combined arms combat team from the 17th Division was also on Bougainville, as well as the usual service and supply units.

For General Hyakutake, “The battle plan is to resist the enemy’s material strength with perseverance, while at the same time displaying our spiritual strength and conducting raids and furious attacks against the enemy flanks and rear. On this basis we will secure the key to victory within the dead spaces produced in enemy strength, and, losing no opportunities, we will exploit successes and annihilate the enemy.”

The Americans moved inland with great difficulty. Colonel Edward A. Craig, commanding the 9th Marine Regiment, recalled, “It was almost impossible to spot our troop movements on operations maps at times. The maps were very poor, and there were few identifying marks on the terrain until we got to the high ground. At one time, I had each company on the line put up weather balloons (small ones) above the treetops in the jungle and then had a plane photograph the area. The small white dots made by the balloons gave a true picture finally of just how my defensive lines ran in a particularly thick part of the jungle. It was the only time during the early part of the campaign that I got a really good idea as to exactly how my lines ran.”

Nevertheless, the Marines pushed inland, fighting off a counter-landing at Koromokina on the left flank of the Marine beachhead by elements of the 17th Division. This was followed by battles for the Piva Trail, the coconut grove along the Numa Numa trail, Piva Forks, Grenade Hill, Hellzapoppin Ridge, and Hill 600A. By December 15, 1943, at a cost of 423 killed and 1,418 wounded, the 3rd Marine Division had established its beachhead securely. On that same date, the Marines began to be relieved by units of the U.S. Army, whose mission was to maintain the beachhead and protect the airfields that were beginning to appear behind the front lines.

First to follow the Marines ashore was the 37th Infantry Division, under the command of Major General Robert S. Beightler. An Ohio National Guard division, the 37th was inducted into Federal service at Columbus, Ohio, in October 1940. After training and maneuvers in Mississippi and Louisiana, the division departed the United States from San Francisco. Along the way it picked up a regiment (the 129th Infantry) of the Illinois National Guard. After further training in the Fiji Islands and Guadalcanal, it entered combat during the New Georgia campaign before arriving at Bougainville a week after the Marines landed.

Major General Robert Sprague Beightler was rare among U.S. Army division commanders during World War II. Born in Marysville, Ohio, in 1892, he was one of the very few National Guard officers to retain command of his division throughout the war. Never attending West Point, General Beightler served in World War I with the 42nd “Rainbow” Division before entering the National Guard. He graduated the Army’s prestigious Command and General Staff School in 1939 and was promoted to major general in 1940, when he assumed command of the 37th Infantry Division.

The first men of the Ohio division to reach Bougainville were an advance party commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Loren G. Windom, the division’s intelligence officer. This group included some headquarters personnel, some reconnaissance troops, and some men from the division’s 117th Engineer Combat Battalion. They arrived with the 21st Marine Regiment on November 6, and immediately began accumulating information on terrain, the division’s assignment, and other essential information to prepare for the Ohio division’s arrival.

The first major combat element of the 37th Infantry Division to sail for Bougainville was the 148th Infantry Regiment. The men boarded four transports and two freighters and sailed lightly burdened, carrying only shelter halves, two canteens, a raincoat or poncho, an extra pair of socks, a spare fatigue uniform, and enough underwear and toilet articles to last 30 days. The soldiers quickly began to enjoy the iced drinking water, canvas berths, and hot showers available to them aboard ship. This idyllic lull lasted until the morning of November 8, when the convoy entered Empress Augusta Bay.

By mid-morning, most of the regiment was on the beach, with only supply details still aboard ship unloading. Suddenly, out of the sun, Japanese bombers and fighter aircraft came screaming down, attacking the transports and freighters that the 148th Infantry had so recently left behind. The ships pulled anchor and headed for the Solomon Sea, while Marine Corps defense battalions opened fire on the enemy with 90mm guns and machine-gun fire. Even riflemen took shots at the low-flying enemy planes.

First Lieutenant Allan W. Hawkins of the 140th Field Artillery Battalion was still aboard the transport Fullerwhen it was hit by a 500-pound bomb. He remembered, “I could see a portion of the action-filled sky through the hatch and witnessed two Jap planes which were hit by antiaircraft shells and fell twisting and burning into the sea. The Navy chaplain was on the intercom giving a play-by-play account. A plane released its bomb and it had us dead center. As it fell lazily toward us, I saw it pass the No. 6 hatch. The ship suddenly lurched, threw everyone off his feet and gave the impression that the whole rear end of the Fullerrose out of the water. I stood up and felt myself all over to see if I were all there, all this time expecting the ship to start sinking.”

The transport didn’t sink, but the Ohio Division suffered its first casualties at Bougainville when two men were killed and eight others wounded.

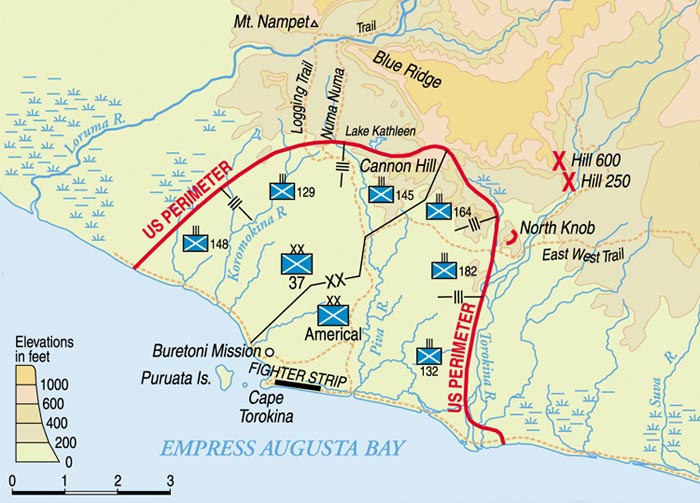

General Geiger’s I Marine Amphibious Corps was needed elsewhere, and so the Army had been tasked to relieve them and hold the Bougainville enclave. To do this, the I Marine Amphibious Corps was relieved by Major General John R. Hodges’ XIV Corps, which included the Ohio Division and Major General Robert B. McClure’s Americal Division. The beachhead was divided between General Beightler’s division on the left (west) and the Americal Division on the right (east).

The Ohio Division men had fought in the jungles before, at New Georgia, and had trained on Guadalcanal, but Bougainville was as bad as anything they had experienced. Everywhere was mud, swamps and jungle. The 117th Engineer Combat Battalion went to work immediately, hacking jeep trails through the thick jungle. It took the 140th Field Artillery Battalion eight hours to move its guns 300 yards to an area where they could set up for firing. Lieutenant Colonel Chet Wolfe’s men had to build their dugouts and firing pits above ground due to the constant high water. Jungle had to be cleared to obtain fields of fire. Snipers were a constant hazard. So were mosquitos. Enemy air raids constantly halted operations along the beach and slowed the development of administrative and supply facilities.

First to move inland was Lieutenant Colonel “Dutch” Shultz’s 3rd Battalion, 148th Infantry. They encountered only stragglers and shell-shocked enemy soldiers who refused to surrender and were eliminated. Meanwhile, the rest of the Ohio Division was en route to the island, all the while under continuous enemy air attack. On November 15, after most of the division was ashore, the men were visited by the area commander, Admiral William F. “Bull” Halsey.

On November 21, the division occupied Defense Line E as a part of the I Marine Amphibious Corps’ beachhead line, relieving Marine units. The 129th and 148th Infantry Regiments occupied the line, while the 145th Infantry was held in reserve. A few days later, the division advanced to Defense Line H with no opposition other than sniper fire and random rounds of artillery. Behind them, the airfields were operational, and American aircraft began to reduce the number of enemy air raids on the beachhead. Army artillery battalions were often called upon to assist the Marines as they expanded their sector of the beachhead.

Thanksgiving passed quietly in the 37th Infantry Division’s sector. Two freighters loaded with turkeys and all the treats had arrived a few days earlier and, despite constant rain and the smell of battle all around them, the infantrymen managed to enjoy their turkey, mashed potatoes, cranberry sauce, hot rolls, butter, creamed cauliflower, coffee and candy.

Things remained quiet until the end of November, when patrols clashed with the enemy at Cannon Hill, resulting in the first casualties in the 129th Infantry since World War I. During this period, patrols were the main producer of combat actions. In one instance, a patrol of the 129th Infantry engaged in what came to be known as the “Battle of the Caves.” The Japanese had established themselves on a steep, sloping hillside, with an almost perpendicular bluff protruding from the side. A narrow ledge had a pathway in the hillside past several natural caves in the bluff. Deep jungle growth provided excellent concealment for the enemy.

A patrol from Company A split into two sections to scout the enemy position. One was to circle the hill and see if the other side offered better access. The second was to climb the hill and clear the caves on their side. As the second patrol advanced up the hill, it was fired upon, and two men were wounded, the rest taking cover under the bluff. They were now trapped, and the Japanese moved out to fire at them. Reinforcements were requested, and when they arrived they moved to ensure that the Japanese could not escape. A battle of rifles, grenades, snipers and machine guns ensued. The wounded were evacuated, but little progress could be made against the enemy-held caves.

Captain Joseph Oleair of Company D made repeated efforts to climb the hill and toss grenades into the caves, but his luck ran out and he was killed by enemy fire. First Lieutenant Robert W. McClellan, the battalion intelligence officer, made similar attempts and suffered the same fate. Captain Oleair received a posthumous Distinguished Service Cross, and Lieutenant McClellan a posthumous Silver Star. First Lieutenant Wilmer W. Stover, who leaped into one of the caves to recover wounded men and carry them to safety under fire, earned another Distinguished Service Cross. By the next morning, the Japanese had gone, leaving several of their dead behind.

Other than patrol actions, little enemy resistance was encountered into 1944. But in February, natives began bringing in rumors of a Japanese force building up outside the American perimeter. General Hyakutake had decided that he had no option but to strike against the American beachhead and destroy it before its aircraft sealed off all avenues of supply and reinforcement to his army on Bougainville. He understood he could only depend upon his own infantry to accomplish this task, knowing that Japanese naval and air forces had been all but driven out of the Solomon Islands. But his inaccurate intelligence assured him that the Americans numbered only 30,000, and that 10,000 of these were aircraft ground crews with no combat value.

General Hyakutake had targeted as a main objective Hill 700, which was on the right flank of the American perimeter at nearly the center of that line. He assigned Lieutenant General Masatane Kanda of the 6th Division three task forces to make the assault.

Each task force was named for its commander. Major General Shun Iwasa would take his 23rd Infantry Regiment and a battalion of the 13th Infantry Regiment along with attached artillery, engineers and mortars, some 4,500 men, and strike the 37th Infantry Division’s right along Hill 700. His ultimate objective was the American airfields at Piva, which he was expected to capture on or before March 10.

Colonel Isashi Magata’s 45th Infantry Regiment composed the second task force, with the usual artillery, mortars, and engineers attached. His 4,300 men were to seize the low ground in front of Hill 700 held by the 129th Infantry Regiment. He, too, was directed to join the Iwasa Unit in taking the Piva airfields.

The third, and smallest, task force was commanded by Colonel Toyohorei Muda, and consisted of 1,350 men of two battalions of the 13th Infantry Regiment and an attached company of engineers. The Muda Unit was to capture Hills 260 and 309 in the American line and then, with support from the Iwasa Unit, capture Hill 608 from the Americal Division’s 182nd Infantry Regiment. This would protect the flank of the Japanese thrust to the Piva airfields. Supporting all this was Colonel Saito, with four 150mm howitzers, two 105mm howitzers, and several smaller artillery guns. Small elements of the 17th Division’s 53rd Infantry and 81st Infantry Regiments would also take part in the attack.

The Japanese had been preparing their plan for months. Work on the native trails to improve them for troop movement had been completed, and the troops supplied with rations for two weeks after which, according to their officers, they would be able to raid captured American stocks. There were between 15,400 and 19,000 Japanese soldiers and sailors gathering in front of the American perimeter, despite the difficulties of organizing, feeding, arming and moving the supporting artillery over native trails. Rains washed away bridges over swollen streams, trails turned to mud, but still the Japanese persevered, and, after a two-day postponement to allow the last units to get into place, the attack was set for March 8, 1944.

Before the attack, General Hyakutake offered his men his own encouragement. His message to his troops read: “The time has come to manifest our knighthood with the pure brilliance of the sword. It is our duty to erase the mortification of our brothers at Guadalcanal. Attack! Assault! Destroy everything! Cut, slash and mow them down. May the color of the red emblem of our arms be deepened with the blood of the American rascals. Our cry of victory at Torokina Bay will be shouted resoundingly to our native land. We are invincible! Always attack. Security is the greatest enemy. Always be alert. Execute silently. Always be clear.”

The Americans knew an attack was coming. In addition to the reports from friendly natives, Australian coastwatchers, radio intercepts, short-range patrols, and prisoner interrogations all indicated a major offensive by the Japanese. An advanced outpost manned by a detachment from the Fiji Infantry Regiment was driven back into the perimeter in February, further evidence of increased Japanese presence near the perimeter.

As March began, the XIV Corps was holding a perimeter that ran in a horseshoe shape through some 23,000 yards of low hills and jungle. The deepest part was near the center, where it was 8,000 yards from the beach and less from the airfields. Defending this horseshoe were the 37th and Americal Infantry Divisions plus the usual support troops; altogether a total of 62,000 American personnel, along with the 1st Fijian Regiment and some native auxiliaries. Each infantry regiment had two battalions on the front lines and one in reserve, for a total of 12 infantry battalions holding the perimeter. These were supported by the 754th Tank Battalion and the 1st Battalion, 24th Infantry, a part of the all-black 93rd Infantry Division that was just arriving on the island.

Behind the front, the 3rd Marine Defense Battalion, the 82nd Chemical Mortar Battalion, and numerous engineer and construction units were available. Most of the combat units had received extra weapons, particularly machine guns and Browning Automatic Rifles (BAR), as well as extra grenades. Oil drums were set up as booby traps, flares were put out with trip wires, and fields of fire were cleared. Eighteen battalions of division and corps artillery were coordinated for defense under Brigadier General Leo N. Kreber, the 37th Infantry Division and acting XIV Corps artillery commander. The XIV Corps was as ready as it could be for the coming attack.

Not everything was perfect, however. Despite their overwhelming strength, the XIV Corps could not man every inch of the front lines with the infantry available. In addition, some key positions, including Hills 700 and 608, were dominated by higher hills that were in Japanese possession. These hills—Blue Ridge, Hill 1000, and Hill 1111—gave the Japanese excellent observation over the American defenses, although they could not see the reverse slopes of the American hills. Despite this, General Griswold believed “The perimeter was as well-organized as the personnel and the terrain would permit.”

Despite being outnumbered and outgunned, General Hyakutake launched his attack at daybreak on March 8 with an artillery bombardment covering the perimeter and the airfields it protected. American artillery observers and Naval gunfire officers were prepared, and soon identified the locations of the Japanese artillery. Counterbattery fire from land and sea began swiftly, as did the attacks of the 1st Marine Air Wing dive bombers. Colonel Saito did manage to destroy four American aircraft on the airfields and damage another fourteen. The bombardment also drove all but a few of the fighters from the fields to safety at New Georgia. Few shells fell on the front lines except in the zone of Colonel Cecil B. Whitcomb’s 145th Infantry, which suffered several casualties.

Hill 700 provided observation over the entire beachhead area, and as such it was vital to the defense. It was held by the 2nd and 3rd Battalions, 145th Infantry Regiment. The hill had steep slopes, which in places were at a 75-degree angle to the ground. Because of this, the Americans had believed that the Japanese would not attack the hill directly. Indeed, the forward slope dropped so steeply that the front of the hill could not be covered by fire. Nevertheless, additional machine guns had been set up, and the Ohio Division’s bunkers contained 37mm guns, machine guns, antitank guns, BARs and riflemen prepared to repulse any such attempt. In support were the 105mm howitzers of the 135th Field Artillery Battalion and the 4.2-inch mortars of Company D, 82nd Chemical Mortar Battalion. Each bunker had been stocked with extra ammunition and C-rations, as well as five-gallon cans of water.

The Japanese sent out wire-cutting parties on March 7, and the following day patrols from the 129th Infantry found aggressive Japanese opposing their advance. At three minutes after seven on the morning of March 8, the first rounds of small-arms fire hit the 2nd Battalion, 145th Infantry atop Hill 700. Artillery rounds continued to fall on the perimeter and against the interior of the beachhead, striking the 6th Field Artillery Battalion, the 54th Coast Artillery Battalion, and the 77th and 36th Naval Construction “Seabees” Battalions behind the Ohio Division. But the American reply was overwhelming, as one prisoner later testified when he remarked, “Each time we fired one round, you send back a hundred in return.”

The American artillery waited until all the infantry patrols had returned to the perimeter before really flexing their might. All four artillery battalions of the Ohio Division—the 6th, 135th, 136th and 140th Field Artillery Battalions—opened fire on Japanese assembly areas without a break. Supported by two battalions from the Americal Division, the barrages were devastating. One surviving Japanese prisoner reported that the 3rd Battalion, 23rd Infantry, was “practically annihilated” by this bombardment. The Japanese survived by pushing close to the American lines to avoid destruction.

The Japanese pushing close to Hill 700 discovered an advantage: once at the base of the hill, they could not be reached by either enemy artillery or small-arms fire. Mortars tried to reach them, but again the steepness of the hill prevented observation of results. Soon the artillery forward observers reported that the Japanese were climbing the hill. Within minutes, Companies E and G, 145th Infantry, began reporting that several booby traps and other warning devices were exploding to their front. The infantry replied with small-arms fire and mortars. Back came Japanese small-arms fire and grenades. Fog and rain made visibility extremely difficult.

Staff Sergeant Otis Hawkins figured out a way to improve his platoon’s visibility. He ordered mortar flares fired. Then, seeing movement in front of his bunker, he pulled wires which set off gallon buckets of oil ignited by phosphorus grenades. With this lighting up his area, Staff Sergeant Hawkins directed 600 rounds of mortar fire on the attackers while his infantry companions’ small-arms fire stopped any attempts at flanking the bunker.

Early the next morning, several Japanese who had infiltrated between Companies E and G were discovered. It was then determined that, under cover of heavy rain and darkness, a battalion of Japanese had used Bangalore torpedoes and dynamite to blast holes in the American barbed wire and were now attacking the forward bunkers of the 145th Infantry. The Americans refused to withdraw and fought where they stood. In one instance, the Japanese attacked an isolated mortar observation post of Company E that was on a knoll at the outer perimeter, known as “Company E nose.” After cutting through three of the four rows of wire protecting the outpost, the Japanese were discovered by a Sergeant Thompson, who opened fire with his BAR. After holding off the enemy for 15 minutes, Sergeant Thompson and his squad withdrew into their bunker and called down mortar fire on their own position, eliminating the attacking force and surviving being shelled by their own mortars.

Not all bunkers held out. In one case, four men from Company G refused to withdraw despite being attacked by a far superior force. They fought with rifles, grenades, and knives before they were overwhelmed. More than a dozen enemy dead were found around their position the next morning.

By dawn, elements of the Japanese 23rd Infantry, 6th Division, held a position on the north slope of Hill 700. To keep them bottled up, the 135th Field Artillery Battalion shelled the enemy while elements of the 145th Infantry extended their perimeter around and behind the Japanese on Hill 700.

Determined to prevent a breakthrough, General Beightler sent forward his only reserve battalion, Lieutenant Colonel Richard Crooks’ 1st Battalion, 145th Infantry, and ordered his 117th Engineer Combat Battalion to move into the vacated reserve positions. At noon, the 1st and 2nd Battalions, 145th Infantry, counterattacked the Japanese on Hill 700. Some positions were recovered, but enemy artillery, mortar, and sniper fire prevented a complete restoration of the original perimeter. Soon the reverse slope was covered with Japanese foxholes, and Japanese reinforcements kept arriving from the foot of the hill.

With darkness the battle subsided, but the Americans could hear the Japanese in the dark filling sandbags and strengthening the American foxholes and bunkers they had captured during the day. Thousands of rounds of American artillery fire seemed to have no effect on the enemy. Two light tanks from the 754th Tank Battalion tried but failed to knock out some of the enemy positions around Hill 700. The Americans suffered 29 killed and 139 men wounded and estimated that 511 Japanese had died on and around Hill 700 on March 9.

The night remained quiet, but with morning came the realization that the Japanese had heavily reinforced their toehold on Hill 700, despite the constant bombardment. To address this problem, a provisional battery from the 251st Automatic Antiaircraft Artillery Battalion moved up and fired their 90mm antiaircraft guns at the Japanese positions from point-blank range. Marine dive bombers pounded the Japanese positions. Artillery battalions continued with an uninterrupted barrage, while the 145th Infantry’s Cannon Company added their guns to the deluge of steel. Japanese reinforcements were spotted moving forward along the Laruma River, and the artillery shifted targets, halting the enemy’s advance.

Assuming the enemy had been sufficiently weakened by this massive display of power, the 1st and 2nd Battalions, 145th Infantry, attacked again in the late afternoon. Using Bangalore torpedoes, bazookas, and pole charges with dynamite, the infantrymen pushed forward against fierce resistance, despite the hour’s long bombardment. Soon the former perimeter was restored except for a 40-yard gap in the line that was still held by four Japanese-occupied bunkers. The fierce fight had left the Americans out of grenades, and Japanese artillery and mortars continued to cause American losses. The division’s 37th Cavalry Reconnaissance Troop was sent forward by General Beightler to take over some of the recovered Company G positions.

During the night of March 10-11, Lieutenant Colonel Russell A. Ramsey’s 3rd Battalion, 145th Infantry, began to hear increased Japanese activity on Cannon Hill, an offshoot of Hill 700. These Japanese were using firecrackers to draw American return fire. The day’s fighting had cost the Ohio Division another seven killed and 131 wounded. Japanese casualties were put at 363 killed. The sectors of the 129th and 148th Infantry Regiments remained quiet, other than several patrol actions.

Late on March 10, the assistant division commander, Brigadier General Charles F. Craig, and the division operations officer, Lieutenant Colonel Windom, visited the frontline battalion headquarters to get a situation report. While they were visiting, Staff Sergeant William A. Orick and two men at the top of Hill 700 were attacked by enemy troops. The two men were bayonetted, and Staff Sergeant Orick evacuated them to the aid station. When he returned, he discovered that one of the enemy dead was an officer with the complete plans for the enemy attack on the Ohio division. The maps and plans were rushed to the division’s intelligence staff for translation and evaluation.

Morning brought a renewed attack on Hill 700. Hundreds of men from the 23rd Infantry, 6th Division attacked in waves shouting “Chusuto” (Damn them!). They occupied an empty bunker atop Hill 700, led by officers brandishing sabers and shouting orders and “Yaruzo” (Let’s do it!) or “Yarimosu” (We’ll do it!). They stormed forward into a heavy fire from the dug-in American infantry, who said little but fought back hard. Yelling “San Nen Kire” (Cut a thousand men!) the Japanese pushed over the bodies of their own dead until the battle was so close that only infantry weapons could be used against the enemy. Both Hill 700 and Cannon Hill were attacked steadily, but the attacks were repulsed with tremendous losses to the Japanese.

Company G’s commander, 1st Lieutenant Clinton S. McLaughlin, was in the center of the battle on his front. He rushed from bunker to bunker to encourage his men, coaching them to fire low and conserve ammunition, stopping only to study the Japanese fire and advance to determine where the most dangerous places were on his line. His clothing was torn by bullets and shrapnel, his canteen shattered, and he was wounded twice. Still in command, when the Japanese approached his most forward position, he jumped into the bunker, already outflanked by the Japanese, and together with Staff Sergeant John H. Kunkel fired point blank at the attackers. The two men killed enough of the enemy to drive the others back. Later, over 185 enemy dead were counted around the position. Both men received the Distinguished Service Cross.

Atop Hill 700, the story was the same as the day before. The Japanese held onto their small breach in the line and continued to attack. Fresh troops kept pouring into the battle, while the Americans were becoming increasingly exhausted and low on ammunition, water, and food. General Beightler ordered Lieutenant Colonel Herbert Radcliffe’s 2nd Battalion, 148th Infantry, forward to assist the exhausted men of the 145th Infantry.

The key to the battle remained the small enemy-held group of bunkers taken on the first day of the battle. To retake these positions, the Americans had to crawl up a precipitous slope with few footholds. This had to be done in the face of withering enemy machine-gun fire, supported with rifle fire and grenades showering down on the attacking American infantry.

Casualties could only be safely evacuated by using the tanks and armored cars of the 37th Cavalry Reconnaissance Troop. That was also the only way supplies could be brought forward. Companies from the 112th Medical Battalion risked their ambulances to speed the recovery of the wounded, and fortunately this succeeded, despite several drivers being wounded in the attempt. But the only sure way to evacuate casualties was by the armored half-tracks, and even they suffered from Japanese mortars and snipers.

Lieutenant Colonel Radcliffe’s battalion decided to surround Hill 700 using Companies E and F in the assault. Company E led off, and 1st Lieutenant Broadus McGinnis and his squad went over the crest together, only to be cut down by Japanese guns. Eight men were instantly killed. Lieutenant McGinnis and three others managed to survive by diving into a nearby trench, capturing a pillbox to which it led. From the captured pillbox, Lieutenant McGinnis shouted back instructions to his men until he was killed by a burst of machine-gun fire. Finally, late in the afternoon, Company E was ordered to stop its attack. Heavy machine guns from Company H were brought up to sustain the Company E gains.

The next morning, Companies E and F attacked again, with Company G in reserve. Using what little cover remained near the hill, both companies moved slowly around it, avoiding enemy machine-gun fire that covered the areas they moved through. Once in assault position, the two companies attacked the hill using smoke grenades, fragmentation grenades, flamethrowers, rocket launchers, and dynamite to clear the way. In one case two soldiers new to combat and barely 21 years of age manned a flamethrower. The team, Pfc. Robert L. E. Cope and Pfc. Herbert Born of Headquarters Company, attacked a pillbox with Japanese troops firing a machine gun and holding up the advance of the 2nd Battalion, 148th Infantry.

Crawling forward and dragging heavy equipment behind them, all the while exposed to the enemy pillbox, they reached a point from which they rose and fired into the enemy position. Once it was destroyed, the team crawled back, recharged their weapon, and repeated the act at a second enemy-held pillbox. They did these four times altogether. Their actions were one of the reasons Headquarters Company, 2nd Battalion, 148th Infantry, received a Distinguished Unit Citation for its work on Bougainville.

Others used different weapons to achieve the same results. Staff Sergeants Jim L. Spencer and Lattie L. Graves volunteered to use a rocket launcher, or “bazooka,” to remove the enemy from Hill 700. Using a trench for cover, the two non-commissioned officers fired the first round. It missed. Excited by the power of the weapon, they immediately reloaded and tried again. This round demolished the pillbox. Thrilled at their success, the two men went on to other targets, with Staff Sergeant Graves yelling, “Make way for the artillery!” as they moved. After three hours, Sergeant Spencer announced that the work was “more fun than a barrel of monkeys.”

Private First Class Jennings W. Crouch and Pfc. William R. Andrick preferred BARs. Both men charged enemy pillboxes with guns blazing from their hips until they had eliminated the occupants of the pillboxes, despite both being seriously wounded. Pfc. John E. Bussard was old for combat, age 36, and the father of three children. But a younger brother had been killed in New Guinea, and he was out for vengeance.

First, despite 12 others being killed or wounded before him, he crawled to an observation position under constant Japanese fire and spent the night there, before returning to report his observations.

The next morning, Bussard knocked out a key Japanese position with anti-tank grenades. Then he volunteered to drag a bazooka up the same hill he had been pinned down on earlier. Carrying the bazooka and his rifle, he again reached his hideout and fired six rounds at the enemy before he was told to return. He then occupied his time by killing several enemy snipers in his company area. He was eventually killed by enemy fire. Later, after the area had been recovered, Pfc. Bussard was credited with the deaths of 250 enemy soldiers.

The battle continued. Pfc. Vernon D. Wilks used his BAR until it burned out, then burned out two more by popping up from a shallow trench and firing before the Japanese could return fire. Captain Richard J. Keller of Company E and 1st Lieutenant Sidney S. Goodkin of Company F led their men over the top of Hill 700. Captain Keller fell to enemy fire, but Lieutenant Goodkin led the two companies over the hill despite painful burns. He tossed grenades and directed his men to clear the Japanese off the top of Hill 700. Staff Sergeant Jack Foust of Company E used a recovered machine gun to clear the treetops of enemy snipers.

Finally, only two pillboxes remained. Sergeant Harold W. Lintemoot and Pfc. Gerald E. Shaner of the battalion’s Ammunition and Pioneer Platoon used six half-pound blocks of TNT on a four-foot board with a slow-burning fuse to destroy the pillboxes. The battle for Hill 700 was over. A final desperate “banzai” charge against Cannon Hill during the night of March 12-13 was well lit by the huge searchlights of the 251st Coast Artillery Battalion, and dawn added 107 more enemy dead to the count. The battles for Hill 260 and others in the Americal Division zone also added hundreds more to the total.

The battle was the costliest the Ohio division had yet fought. Over 1,500 enemy dead were buried after the fighting ended, and others lay uncounted in caves and deep jungles. It was only on March 28 that General Hyakutake acknowledged defeat and ordered a withdrawal. The XIV Corps pursued, leading to more battles and pushing the Japanese well away from Cape Torokina. During the pursuit, elements of the 93rd Infantry Division received their first combat experience.

Like the Marines before them, XIV Corps was needed elsewhere, specifically to retake the Philippines, and beginning in December 1944, the 37th Infantry and Americal Divisions were on their way to the Sixth and Eighth Armies, respectively. They were replaced by the 3rd Australian Infantry Division, a part of Lieutenant General Sir Stanley Savige’s II Australian Corps. The Australians would spend the rest of the war in the deadly, unglamorous, and frustrating job of mopping up strong Japanese forces remaining on Bougainville. Except by those who fought there, Hill 700 was forgotten.

Nathan N. Prefer is the author of several books and articles on World War II. His latest book is titled Leyte 1944, The Soldier’s Battle. He received his Ph.D. in Military History from the City University of New York and is a former Marine Corps Reservist. Dr. Prefer is now retired and resides in Fort Myers, Florida.