By Dick Camp, Col., USMC, Ret.

Superior Private Tomisaburo Sawa of the Imperial Japanese Army fixed the bayonet on his Type 99 Arisaka rifle and carefully checked to make sure the weapon was loaded. From his position on the veranda of the prison guard barracks, he watched as members of his platoon advanced across the courtyard. The POWs that Sawa were in charge of didn’t know it, but many would soon become victims of the now-infamous Palawan massacre.

U.S. Marine Corps Pfc. Glenn “Mac” McDole saw the Japanese soldiers coming from the entranceway of his trench air raid shelter and knew instinctively that something was terribly wrong.

The Japanese guards were in full combat gear, with bayonets fixed. There was a guttural order, the line stopped, and the Japanese quickly formed a semi-circle around the trenches filled with American POWs.

“I saw five [Japanese] soldiers go up to one of the air raid shelters and throw buckets of gasoline into the entrance,” Private Sawa stated. “This was followed by two men, who threw lighted torches into the opening.”

McDole watched horrorstruck as flames engulfed the trapped Americans. He saw one human torch climb out of the trench and run screaming toward the enemy. They shot him down, unintentionally putting the man out of his misery.

Others were not so lucky. The guards watched them burn to death in agony. McDole ducked down, terrified at what he had seen. “My God,” he thought, “the Japanese are going to kill us all.”

Building “Roads” at the Death Camp

With the surrender of U.S. forces in the Philippines in 1942, American prisoners of war were immediately confined in filthy, overcrowded POW camps near Manila. McDole was sent to the infamous Cabanatuan No. 1, where he quickly decided that it was nothing but a death camp. Ten to 15 men died every day of malnutrition, vitamin deficiency, and a variety of contagious diseases. “I never saw so many fellows dying each day,” McDole recalled. “No medicines or anything.”

In addition, many prisoners were executed by their brutal, sadistic guards for a variety of trumped-up charges. McDole knew that it was only a matter of time until the same thing happened to him, and he searched for a way to get out of the camp. It finally came in the form of a large working party. “Want men, want men,” the guards shouted out. “Three hundred go to Manila.” Envisioning better conditions, McDole quickly raised his hand despite the old Corps adage (“Never volunteer”).

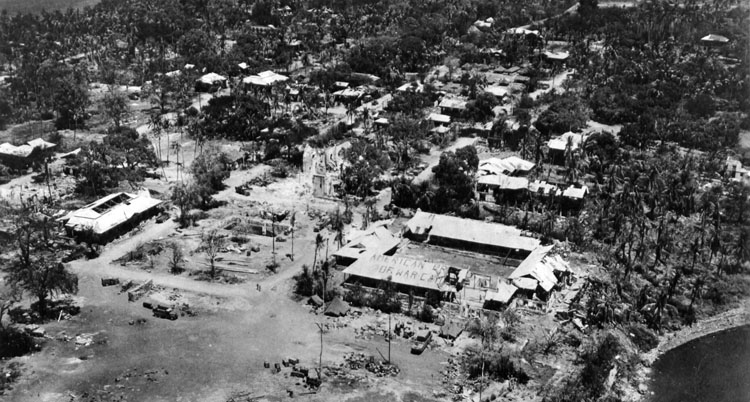

On August 12, 1942, he was taken to Palawan, one of the largest islands in the Philippines—270 miles long and 15 miles wide, located on the western perimeter of the Sulu Sea—and marched to an old, dilapidated Filipino Constabulary barracks, his home for the next two-and-a-half years. He passed through the stone entranceway, along a dirt road lined with a dozen coconut trees to a courtyard in front of a U-shaped barracks building.

The prisoners were met by the commander of the 131st Airfield Battalion, Captain Nagayoshi Kojima, nicknamed “the Weasel” by the POWs.

“Kojima stood on a little pedestal so he could look down on us,” McDole remembered. “In a squeaky voice, he would say, ‘Americans—’ and then pause.

‘Today we build roads.’ It wasn’t long before we knew it was a lie … we were to build an airstrip.” McDole was incredulous. There was nothing around the camp but thick jungle.

A Life of Poor Food, Little Medical Aid, and Brutal Treatment

The prisoners started to work almost immediately, felling trees, hauling and crushing coral gravel, and pouring concrete, day after day without adequate rest or food. “It was all hand labor,” McDole emphasized, “with only a level mess kit of rice and an occasional bowl of mongo bean soup to keep us going.”

Food became an obsession; the prisoners thought of it night and day. McDole dreamed of angel food cake and ice cream. Others made up elaborate menus they intended to eat upon liberation. In the meantime, they had to do with what they could scrounge: lizards, birds, monkeys, snakes. In fact, McDole rather took a fancy to roasted snake. “Tastes just like chicken,” he claimed.

Many of the prisoners became sick and unable to work, while others suffered from Japanese brutality. “We had so many fellows sick and beat up,” McDole recalled, “that they filled one wing of the barracks, which we called sick bay.”

The term “sick bay” was a misnomer, because there were no medicines, and the men were put on half rations if they did not work. “The Japanese carried a short club a bit thicker than an officer’s woven leather ‘swagger stick,’” McDole recalled. “The guards were expert at applying it to the kidneys or the back of the head. They could drop a man with one blow.”

One guard caught two prisoners taking green papayas from a tree in the compound and punished them by breaking their left arms with an iron bar. One day at work, McDole was doping off and got caught. A guard hit him on the head, dropping him to his knees. Foolishly, McDole got up, looked him in the eyes and said, “Ya didn’t hurt me, you SOB!” The guard hit him—and down he went again.

Furious, McDole got up and yelled, “Ya still didn’t hurt me!” Other prisoners looked on, knowing that the guard could easily kill him for insubordination. Instead, the Japanese soldier just shook his head and said, “Ya baka (You’re crazy)!” and walked away.

Other prisoners were not as lucky as McDole. The Japanese learned that several POWs had made contact with the local Filipinos, who gave them information and food. The men were tied to the courtyard coconut trees and beaten in front of the rest of the prisoners. One of the men was thrashed with a wire whip, which tore his flesh to the bone. When one guard tired, another took his place. The men were beaten unconscious, dragged to a cell and put on a ration of half a mess kit of rice every three days.

Even with the close supervision and threat of dire punishment, several prisoners managed to escape—but not all of them made it to freedom. Two POWs who had made it through the wire managed to elude capture for six days before being dragged back to the camp. They were severely beaten before the assembled prisoners until unconscious and then loaded on a truck and taken away. Filipinos said they were shot and buried in unmarked graves.

McDole Gets an Emergency Appendectomy Inside the Palawan Camp

There was one American doctor in the camp, but the Japanese would not give him any medicine, so he relied on his own remedies, which, fortunately for McDole, were good enough.

On March 14, 1943, McDole desperately needed the doctor’s expertise. “I was busting rock when I suddenly broke out in a cold sweat. I grabbed my side and down on my knees I went. The next thing I knew a guard was beating the heck out of me, telling me to get back to work.” The American doctor convinced the guard that McDole was really sick and got him back to camp.

He was diagnosed with acute appendicitis and told he would die without an immediate operation. The catch was, there was no anesthetic. McDole responded bravely, “If I’m going to die, let’s die trying.” He was held down on a table by five guards, who made fun of his screams as the doctor operated.

“It took him two hours and fifty minutes to get the appendix out and suture me back together,” McDole recalled. Unfortunately, infection set in and he was close to death. One night his abdomen ruptured, spewing a noxious mixture of pus and blood on the deck. The doctor tried sewing the wound shut but the thread would not hold in the mutilated skin. When that failed, the doctor took shirt buttons, lined them up alongside the incision and sewed it up, which left a rather unique scar. After weeks of recovery, McDole was finally well enough to go back to work.

Help from Above?

By mid-October 1944, the prisoners were startled by the appearance of American B-24 Liberators overhead, which began to systematically bomb the airfield. In one memorable raid, they destroyed 60 Japanese planes on the ground. Their arrival verified the rumors that an American invasion force was approaching the Philippines.

The POWs were overjoyed, but at the same time worried. They had heard that the guards were under orders to kill all the prisoners if the Americans invaded the island. The camp commander decreed that the POWs had to dig trenches roofed with logs and dirt to serve as air raid shelters.

Three large and several smaller two- and three-man shelters were scattered around the prison compound. Shelter A held 50 men, Shelter B held 35, and Shelter C had room for 25 to 30 prisoners. The large shelters were five feet deep, four feet wide, and up to 150 feet long. In accordance with Japanese orders, there was to be only one entrance, small enough to admit only one man at a time. The prisoners were instructed to get in the shelters when the air raid alarm sounded.

POWs Burned Alive

On December 14, 1944, the prisoners unexpectedly returned to camp after spending the morning filling bomb craters on the runway. One of McDole’s friends whispered to him, “Something’s going on, Dole. What the hell do you think is happening?”

The camp commander appeared and announced, “Americans, your working days are over.” At this pronouncement, most of the men believed that the invasion was coming, and they would soon be free. Suddenly, the air raid siren wailed and the guards started screaming to get into the bomb shelters, their shouts punctuated by rifle butts and clubs.

McDole made a beeline for Shelter C, which was located on the edge of a 60-foot cliff. After some time, with no sign of planes, McDole was encouraged to look out “and see if you can see anything going on.”

Lieutenant Sho Yoshiwara ordered the men of his company into formation and told them to load five rounds of ammunition and fix bayonets. Superior Private Sawa remembered that, “Captain Kojima appeared and announced that it was necessary to kill all the POWs.”

The company formation marched into the camp where “Lieutenant Yoshiwara personally directed the placement of individuals and issued the necessary objectives and methods of killing,” Sawa stated. “He ordered those with rifles and machine guns to kill any POW who came out of the air raid shelters.”

As McDole peered out of the entranceway, he saw several guards carrying buckets of liquid. Others carried lighted torches. He watched as they poured the contents of the buckets into Shelter B and threw in the torches. There was a muffled “WHUMP!” and a burst of flame. Horrorstruck, McDole heard agonized screams as the men inside burned. He ducked back inside the trench and screamed, “They’re murdering the men in the B Company pit! Finish digging the tunnel!”

Unbeknownst to the Japanese, the inhabitants of Shelter C had dug it to extend beyond the barbed-wire fence, with only a six-inch plug of earth in place to conceal an emergency exit. McDole took another quick look to see if the Japanese were getting close. He was horrified by the carnage—men engulfed in flames, guards bayoneting, shooting, and clubbing the helpless Americans. The scene was almost beyond comprehension.

McDole’s buddy, Marine Sergeant Douglas W. Bogue, who was also in Shelter C, “saw several Americans, while still burning or wounded, rush the Japs and fight them hand to hand. One American, whom I could not recognize in the confusion, succeeded in tearing a rifle from one Jap and shooting him before being bayoneted to death.”

Sawa admitted at the war-crimes trial that “seven or eight POWs came running out of one of the shelters. Lieutenant Yoshiwara yelled out, ‘Shoot them. Shoot them!’ The light machine gun on the veranda near my post went into action and leveled these POWs to the ground, killing each one of them. I opened fire with my rifle and believe I dropped three of them. After that, Yoshiwara and another soldier threw two hand grenades into a trench. I also saw two or three POWs bayoneted and one killed by a sword.”

As McDole kept watch, the prisoner at the end of Shelter C clawed the earth in a frenzy, quickly breaking through and widening the hole. One by one the men pulled themselves out of the opening and tumbled down the cliff to the beach. Suddenly burning gasoline splashed on the floor of the trench, setting one man on fire.

It was now or never for McDole. He shoved the last man out and jumped. The screaming of the burning man stayed with him as he stumbled and fell to the beach.

Escaping the Palawan Massacre

Bogue was also lucky to escape the trench, but he had to tear through a barbed-wire fence with his bare hands to reach the cliff. There McDole ran into his best friend. “This is it, buddy, isn’t it?” McDole gasped.

Suddenly, rifle fire erupted from the top of the cliff. The two men ran; bullets impacted all around them as they desperately sprinted for a hiding place. McDole spotted the camp’s garbage dump and dove into the rotting mass. The smell was overpowering, but he pushed deeper and deeper until he was completely covered. He ignored its loathsome inhabitants—worms and maggots—and forced himself to remain still. Within minutes, two other escapees burrowed into the mound.

Muffled shots penetrated the garbage pile. One of the buried men panicked, jumped up, and ran for the water. He was immediately gunned down. Another just stood up and shouted, “All right, here I am and don’t miss me, you SOBs!” A volley of shots ended his shout.

McDole gutted it out until morning when he was almost discovered; a guard was almost close enough to touch. Suddenly, another escapee was discovered and the guard ran off. Taking advantage of the distraction, McDole fled the dump and took refuge in a sewer outlet where he found a badly wounded prisoner. The two tried to swim across the bay but the man was too weak. McDole stayed with him until he succumbed to his wounds.

Bogue, meanwhile, escaped the guards’ attention and found a small crack in the rocks to hide in, “all the time hearing the butchery going on above. The stench of burning flesh was strong.” The incoming tide forced him to move.

“While crawling about, I found four others,” he recalled. “We decided our only chance was to swim across the bay.” Bogue became separated from the others and spent the next five days wandering around the jungle without food or water. He was finally rescued by prisoners from, of all things, the Iwahig Penal Colony, a jail for locals convicted of low-level crimes. The prisoners fed and clothed him—and contacted the local guerrilla organization, which took him under their control.

Once a POW, but no Longer

On the evening of December 18, three days after the Palawan massacre, a badly weakened McDole slipped into the water and began the five-mile swim. He was in the water all night—arms and legs numb and almost useless—until he collapsed on the beach shortly before dawn. He found a coconut, cracked it open, and drank the milk, which helped him regain some of his strength.

As daylight emerged, he saw huts across the bay and decided to swim to them, praying it was a friendly village. Halfway across, just before his strength gave out, he spotted a wooden fishing trap, climbed aboard, and passed out. He awoke the next morning to the smell of food being cooked in the village—and the sight of a native fishing boat approaching the trap. He half rose and they spotted him.

“Hey Joe,” a Filipino called out, “you a POW?” McDole responded weakly, “I was, but no longer.”

McDole was so feeble that the natives had to carry him to shore and into a hut, where they cleaned him up and fed him “the most wonderful fish and rice bread I had ever tasted.” Shortly thereafter, he was happily reunited with Bogue.

The two rested one day and then were forced to flee after word was received that a Japanese patrol was headed their way. On Christmas Eve, they were on a hill overlooking a Filipino village, just as the sun was setting. Their escorts stopped and, in almost perfect English, sang, “God Bless America.” Both Americans broke down in tears when one of the natives said, “My friends, you are now in the free Philippines!”

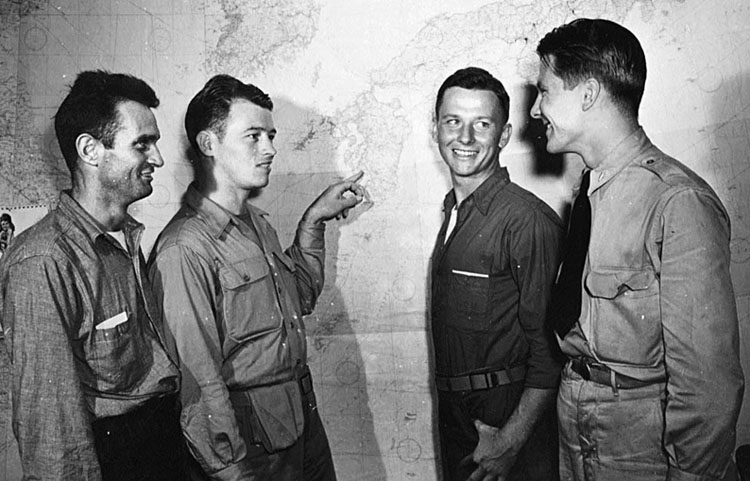

Palawan Aftermath: What Became of McDole and the Japanese Guards

Marine Private First Class Glenn McDole was evacuated from the Philippines on January 21, 1945. He was one of only 11 survivors of the 159 American POWs that died in the Palawan massacre. An Army mortuary unit excavated the burned and destroyed dugouts after the war. The unit reported 79 individual burials and many more partial burials; the skeletons either had bullet holes or had been crushed by blunt instruments.

Most of the remains were found huddled together at a spot farthest away from the entranceway, in an attempt to escape the fire. In two dugouts, remains were found in a prone position, arms extended, with small conical holes at their fingertips, showing they were trying to dig their way to freedom. In 1952, the remains of 123 victims were interned at the Jefferson Barracks National Cemetery, near St. Louis, Missouri.

The Japanese fared considerably better then their prisoners after the war. The senior Japanese officer was tried and sentenced to hang but the sentence was reduced to 30 years imprisonment. Only 14 Japanese guards were brought to trial. The others could not be found. Six were acquitted, and the others received prison sentences ranging from two to 12 years.

Superior Private Sawa appeared at the trial somewhat the worse for wear. One of his guards, the indomitable Sergeant Bogue, admitted to beating the hell out him. Sawa received a five-year sentence despite Bogue’s request to have him hanged.

After discharge, Glenn McDole became an Iowa highway patrolman for 29 years and a Polk County sheriff. He was called up for the Korean War and served one year at Camp Pendleton, California, before hanging up his Marine uniform for good.

After retirement, he shared his story about his experiences during the Palawan massacre in presentations at schools, church meetings, and community organizations so that the men who died there will not be forgotten. Glenn McDole’s memoir, Last Man Out, published in 2004, is an account of his POW experiences. He died in 2009. (Get more first-hand accounts of the Second World War, from the hedgerows of Europe to the jungles of the South Pacific, by subscribing to WWII Quarterly magazine.)