By Patrick J. Chaisson

For Australian coastwatcher Ruby Boye, an Allied agent stationed on the South Pacific island of Vanikoro, it started much like any other morning. She had just broadcast a routine weather report when her radio receiver suddenly hissed into life.

“Calling Mrs. Boye,” spoke a heavily accented voice. “Calling Mrs. Boye on Vanikoro.”

Ruby was stunned into silence—no Australian or American sounded like that. Then her caller delivered an ominous warning: “Japanese commander say, you get out … or else!”

As Australia’s only female coastwatcher, Ruby Boye monitored enemy activity from an extremely remote location far from friendly military forces. Aside from the ever-present threat of death or capture at the hands of Japanese soldiers, she faced a daily struggle just to survive on harsh, unforgiving Vanikoro. Yet this indomitable woman remained at her island post for the entire four-year Pacific War.

The Early Life of Ruby Olive Jones

Born on July 29, 1891, Ruby Olive Jones grew up in a suburb of Sydney, Australia, where as a youth she enjoyed the piano. In 1919 Ruby married Skov Boye, a laundry proprietor, who gave her two sons. In 1928 the Boyes moved to Tulagi, British Solomon Islands Protectorate, where Skov worked as a plantation manager for Lever Brothers.

Eight years later, he took a job with the Kauri Timber Company on Vanikoro, Santa Cruz Islands. Part of the Solomon Archipelago, Vanikoro comprises five mountainous, volcanic islets ringed by a treacherous coral reef. It sits approximately 500 miles southeast of Tulagi and Guadalcanal, in a region Ruby wryly described as “the hurricane belt.”

Conditions on roadless Vanikoro were extremely primitive. Skov and Ruby lived in the village of Paeu along with about 20 European contract employees, including a doctor and radio operator. Another 80 indigenous workers labored high in the mountains, harvesting giant logs destined for Australian markets.

Four times per year, a cargo ship from Melbourne negotiated Vanikoro’s hazardous barrier reef to collect this timber. It also delivered supplies and mail. Every two years, the Boyes took a three-month leave of absence to visit their sons Ken and Don who were attending school in Australia.

Aside from these infrequent encounters with the outside world, Skov and Ruby’s life on Vanikoro was measured chiefly by the violent tropical storms that lashed their island paradise. As time passed, the Boyes could sense another storm brewing across Pacific skies. This coming tempest, however, was entirely the work of man.

Others also saw war clouds forming. Royal Australian Navy (RAN) Lt. Cmdr. Eric Feldt, a reservist with long experience in New Guinea, began in 1939 to organize and expand a network of observers stationed on the islands to Australia’s north. He recruited these coastwatchers from European planters and missionaries who were familiar with the islands, knew the native peoples living there, and who could survive on their own for long periods of time.

Eventually, more than 600 Australian, American, and British coastwatchers established outposts in Papua New Guinea and the Bismarck Archipelago, as well as all across the Solomon Islands. (Read all about the events of the South Pacific from those who lived through them inside the pages of WWII History magazine.)

Japan Invades: Ruby Boye Joins the Coastwatchers

After Japan invaded the Southwest Pacific in late 1941, many of these hardy volunteers found themselves deep inside enemy territory. Constantly hunted by Japanese patrols, they lived by their wits and long experience on the islands. Combat was to be avoided. The special call-sign “Ferdinand” (taken from the popular children’s book about a bull who preferred to smell flowers instead of fighting matadors) was intended to remind Feldt’s coastwatchers of their role as information gatherers, not soldiers.

The coastwatchers’ primary mission involved monitoring enemy air and ship movements. Individual spotters sent observations via courier to a central station, where these reports were transmitted via wireless to Commander Feldt’s headquarters. Their primary teleradio was the RAN-issue Type 3B, a versatile, portable set that could broadcast in either voice or “continuous wave” (Morse Code) mode over long distances.

Apart from their intelligence-collecting chores, coastwatchers also rescued stranded Allied sailors and airmen. Famously, Australian coastwatcher Lieutenant Alan “Reg” Evans helped save the lives of 11 Americans—including future U.S. President John F. Kennedy—marooned in the waters off Kolombangara after their patrol torpedo boat, PT-109, was cut in two by a Japanese destroyer on the night of August 2, 1943.

A coastwatcher station came to Vanikoro sometime in 1941, complete with a powerful 3B teleradio and an operator trained to make meteorological observations. Allied officers knew that weather patterns generated in the Santa Cruz Islands often influenced conditions throughout the Solomon chain. This data would soon prove indispensable, but first a problem arose—one requiring an unorthodox solution.

The radioman assigned to Vanikoro desperately wanted to leave his post and enlist in the Royal Australian Air Force. No replacement was immediately available, so Ruby Boye volunteered to learn his duties. Before long, she was transmitting weather observations four times a day to the coastwatchers’ regional headquarters on Tulagi.

As Japanese forces advanced ever closer to mainland Australia during the first months of 1942, Allied authorities suspended all merchant activity throughout the Solomons. With Vanikoro’s logging operation now shut down, the timber company chartered a ship to evacuate its employees.

“What a sad day that was for us,” Ruby later remembered of her co-workers’ departure. Yet she and Skov did not accompany them off the island. “My husband chose to remain for the company’s interest,” she explained, “attending to the maintenance of the rolling and floating stock, machinery, houses, etc.”

Having joined the coastwatchers, Ruby Boye felt obliged to remain as well. “I decided it was my duty to stay also to continue to operate the radio,” she remarked in a 1998 interview. To keep busy, she started teaching herself Morse Code—a wise move, as things turned out.

Pulling Teeth, Arbitrating Agruments: How the Boyes Supported the Vanikoro Locals

Skov and Ruby, now the only Europeans on Vanikoro, lived peacefully among several hundred indigenous inhabitants. These people often came to the Boyes seeking help with domestic disputes, dental problems, or other medical emergencies. Skov, Vanikoro’s island manager in prewar times, felt responsible for the populace’s health and happiness—beliefs Ruby shared. Over the next several years, the Boyes skillfully arbitrated quarrels, pulled teeth, and treated ailments all across the chain of islands.

Those who knew her remembered Mrs. Boye as a dark-haired woman who, at 5 feet, 10 inches in height, towered over her Vanikoran neighbors. Ruby’s imposing presence, however, was softened by a gentle laugh and helpful spirit. Utterly self-reliant, she ably balanced her coastwatcher’s duties with the countless domestic chores required of an Australian housewife living at the extreme edge of civilization.

In May 1942, a planter named Charles Bignell sailed from the Central Solomons with urgent news. The Japanese, he reported, had invaded Tulagi on May 3 and taken over the British colonial capital there. Its local defense force had been quickly overwhelmed, forcing the island’s remaining European inhabitants to either surrender or, like Bignell, make their escape.

The enemy was closing in. Before departing Vanikoro with food and fresh water, Bignell warned of a Japanese cruiser spotted lurking among the Santa Cruz Islands. Long-range reconnaissance planes also began appearing overhead, their Rising Sun insignia unmistakable to Ruby’s eye. Her regular weather observations were now accompanied by occasional reports of aircraft sightings.

Receiving Death Threats from Japan

Japanese intelligence officers knew all about Mrs. Boye and the work she was performing. When radio-delivered threats failed, a flying boat dropped pamphlets over Vanikoro that offered money in return for the death or capture of the island’s “European spies.”

Ruby also recalled hearing loud motors and seeing bright flashing lights coming from just outside Vanikoro’s poorly charted barrier reef late one evening. She believed it was an enemy vessel trying to enter the lagoon. After four or five tense hours, though, the intruders apparently gave up and sailed off.

The Boyes knew what usually happened to coastwatchers who fell into Japanese hands. In March 1942, an elderly Australian copra planter named Percy Good was executed by enemy troops on Bougainville in the western Solomon Islands. As civilians, Skov and Ruby would likely share Good’s fate if captured. They agreed that in the event of an actual landing they would flee into the jungle, committing suicide if necessary rather than subject themselves to torture, starvation, and eventual death at the hands of ruthless Japanese interrogators.

As a further precaution, the Boyes moved their radio transmitter from its location in Paeu to a more remote site across the Lawrence River. This led to a new set of dangers, especially after a cyclone destroyed the bridge connecting Ruby’s house with her teleradio. She then had to row across the river in a tiny skiff, an especially perilous journey after dark when Vanikoro’s resident crocodiles became most active.

“I kept out of their way and they kept out of mine,” Mrs. Boye later remarked about the voracious reptiles. “But they were particularly fond of dogs and cats and would often come and take them from under the house.”

Everyday life on Vanikoro meant enduring such hazards as hurricanes, earthquakes, and deadly tropical diseases. Ruby contracted malaria several times, along with an infection known as blackwater fever which, the doughty coastwatcher observed, “usually proves fatal.” Somehow, she survived.

Shortly after that threatening radio message came through, some U.S. Navy sailors paid the Boyes a brief visit. They adjusted Ruby’s transmitter frequencies and advised her to begin broadcasting in Morse Code (which she had just learned). The Americans also left behind a welcome gift of combat rations to supplement the couple’s dwindling stock of native vegetables, tropical fruit, and fish.

Mrs. Boye seemed more amused than alarmed by the fuss that everyone was making over her. “The mere fact that I was annoying them [the enemy] sufficiently to have them warn me off was somewhat gratifying,” she said.

Bull Helsey Meets Ruby Boye, “The Wonderful Lady Who Operates the Radio”

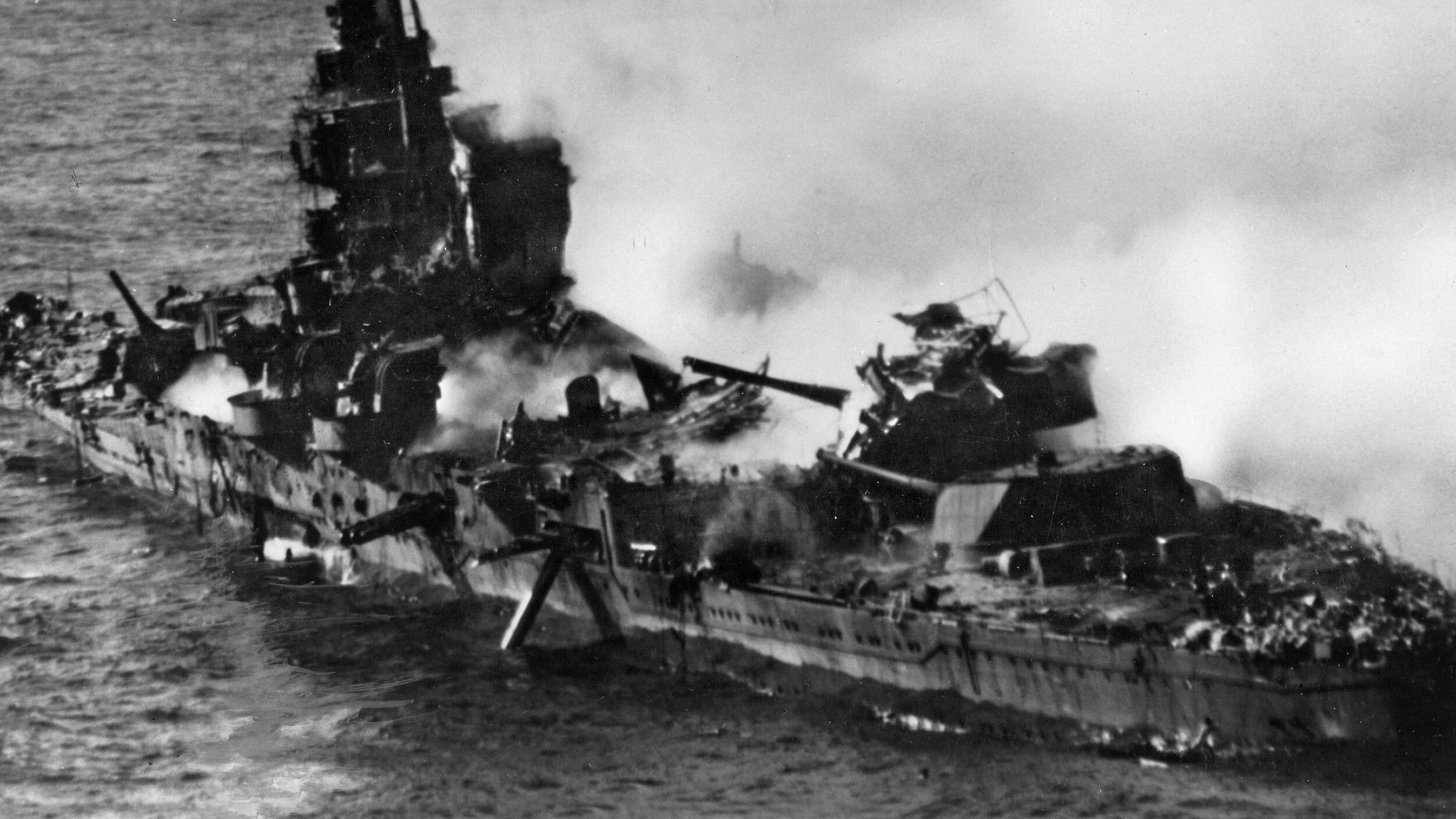

With the loss of Tulagi, Vanikoro became a relay station between the American headquarters at Vila in the New Hebrides and coastwatchers operating far behind enemy lines to the west. Ruby’s enciphered meteorological observations also gave the Allies a key advantage during the Battle of the Coral Sea (May 4-8, 1942), the invasion of Guadalcanal (August 1942), and the Battle of Santa Cruz (October 25-27, 1942).

This last engagement, while a tactical victory for Japan, marked the sunset of that nation’s ambitions in the eastern Solomons. No longer would its fleets of warships and aircraft threaten the ever-expanding Allied presence across this region. Instead, naval vessels flying the U.S. and Australian national ensigns became more and more common in the waters off Vanikoro.

“Our harbor was later used for the American aircraft tenders servicing Catalinas (Consolidated PBY flying boats) on reconnaissance flights,” Ruby remembered. “We made many friends and enjoyed the company.” The Boyes also enjoyed their generous guests’ gifts of food and provisions.

The U.S. Navy’s presence there did not go completely unchallenged, though. “One day, the enemy attacked one of the tenders in the harbor,” she recounted. “Little damage was done but the Japanese lost three of their eight planes in the action.”

Sometime in 1943, Ruby Boye received a high-profile visitor when Admiral William F. “Bull” Halsey arrived by seaplane to congratulate the coastwatcher on her wartime achievements. Admitting he was “playing hooky” from his duties as commander in chief, South Pacific Area, Halsey introduced himself by exclaiming, “I want to meet the wonderful lady who operates the radio here.”

Admiral Halsey also helped Ruby obtain medical treatment when she contracted the shingles. He arranged for a Catalina to take her from Vanikoro to Australia, leaving behind four sailors to run the radio station during her three-week convalescence. Mrs. Boye said all four men begged to stay on Vanikoro after she returned to duty.

Australian officers were also impressed by this self-taught wireless operator, the sole female coastwatcher to serve during World War II. Commander Eric Feldt arranged for her appointment as Honorary Third Officer in the Women’s Royal Australian Navy Service (WRANS), effective July 27, 1943. Ruby was 51 years of age when she accepted this commission.

Shortly thereafter, the Boyes’ teleradio—normally reserved for urgent military message traffic—relayed a most unusual request. Headquarters wanted Ruby’s dress size, a demand that baffled both the coastwatcher and her husband. All questions were answered in a few days when an Allied transport aircraft appeared overhead, parachuting into the lagoon a waterproof canister that contained her new WRANS uniform.

“It caused some excitement, as you can imagine,” Ruby said of this incident.

Returning to Life as Normal

As battle lines moved westward, life on Vanikoro began returning to its prewar rhythms. Allied warships called less and less frequently—the Boyes once went 10 months without resupply. News also took longer to reach them. In late 1943 His Majesty’s Resident Commissioner for the Solomon Islands nominated Ruby for the British Empire Medal, but due to a bureaucratic foul-up it was not until 1946 that she actually received this prestigious decoration.

Third Officer Boye’s other awards included the 1939-1942 Star, the Pacific Star, the War Medal, and the Australian Service Medal. As her WRANS commission was strictly honorary, though, Ruby never received pay for the service she performed as a coastwatcher.

Skov and Ruby remained on Vanikoro until 1947, when he sickened with leukemia. The Boyes returned by chartered airplane to Sydney, where Skov Boye died shortly after being admitted to the hospital. Settling in Sydney, Ruby married Frank Jones in 1950. Sadly, she lost Frank after 11 years of wedlock.

For the next three decades she lived by herself in a small flat near Sydney. Surrounded by “a good family and many friends,” Ruby often shared her tales of wartime adventure with fellow WRANS, other veterans, and local schoolchildren. Fiercely independent despite mounting health problems, she was finally persuaded to apply for a military pension in her 87th year.

Honorary Third Officer Ruby Boye lived to the age of 99, passing away on September 14, 1990. Her contribution to the Allied victory in World War II has been commemorated by the dedication of an accommodation block—Boye House—at the Australian Defence Force Academy in Canberra.

Patrick Chaisson, a retired U.S. Army officer and historian, writes from his home in Scotia, New York