By David Norris

Cannons roared and muskets crackled in the darkness below the hill of Rodewitz, but King Frederick the Great of Prussia was in no hurry to move. During this campaign, many a night’s sleep had been

cut short by noisy predawn attacks by Croatian pandours serving with the Austrian Army. Soldiers encamped near his quarters rushed to take up arms, but he scoffed, “What are you about, lads? It is nothing—only those scoundrels the Croats!” But this time, the firing heralded more than a mere picket-line skirmish. It was not yet dawn, but tens of thousands of Austrian grenadiers, regular infantry, cavalry, and gunners had already smashed the right flank of the Prussian Army at the village of Hochkirch in Saxony. Thousands of Prussian soldiers awoke to the sound of captured guns turned to rake their camps with shot and shell.

One of the greatest military strategists of the 18th century had been taken completely by surprise. The next few hours of the morning of October 14, 1758, would tell whether Frederick the Great’s Prussian Army would survive the Battle of Hochkirch.

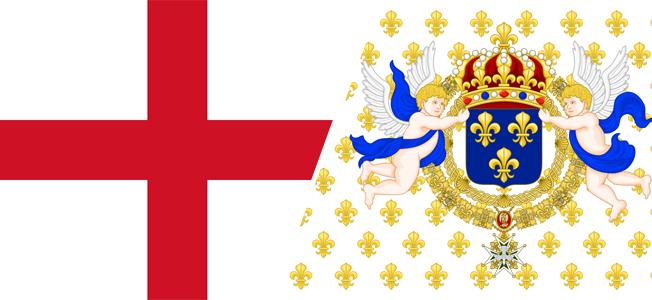

The Seven Years’ War was in its second year. Frederick the Great’s Prussian Army held the German lands of Silesia and Saxony. Surrounded by the great empires of France, Austria, and Russia, Frederick deftly parried attacks from vastly greater armies than his own with the limited help of allied German states, and financial aid and some troops from King George II of Great Britain.

The Prussian king had some advantages that helped balance the odds against him. He possessed uncanny ability as a strategist and military leader, and he held seemingly boundless confidence in his own strategic and political skills. Most important of all, his system of intense training and discipline mixed with his willingness to share the hardships of campaigning with his soldiers won him their devotion.

In the summer of 1758, another threat to Prussia materialized when a Russian army under General Wilhelm von Fermor marched from the east toward the Oder River. Frederick took most of his troops to deal with the Russians, leaving a 20,000-man army in Saxony under his brother, Prince Henry of Prussia. The prince’s small force faced an Austrian army of 90,000 men under Field Marshal Count Leopold von Daun.

On August 25, 1758, Frederick won a narrow and costly victory over the Russians at Zorndorf, a place now in western Poland. A few days later, General Fermor withdrew with his battered army, and Frederick hurried to rejoin his brother in Saxony. On October 8, Daun’s army arrived to confront Frederick and camped at Kittlitz, about 40 miles east of Dresden.

Frederick the Great’s army was largely drawn from his dominions. His kingdom, a growing European power, included several noncontiguous parcels stretching from the Dutch border to the Baltic, in addition to the larger regions of Brandenburg and East Prussia. The Austrian force, in contrast, was a multilingual combination of soldiers from the German-speaking lands of Austria, as well as Croatians, Italians, Hungarians, and troops from other Hapsburg lands. Frederick ruled perhaps four and a half million subjects, compared to 25 million living in the Austrian dominions.

Among Frederick’s commanders was one of his few close friends, Field Marshal James Francis Edward Keith. Exiled after serving in the ill-fated Jacobite rebellions of 1715 and 1719 in Scotland, Keith served with the armies of Spain and Russia before accepting a commission from Frederick the Great in 1747. The Prussian king appreciated the Scottish officer not only as a brave and dependable battlefield commander, but also as a sophisticated and cultured gentleman. The Prussian king promoted Keith to field marshal, and Keith’s sterling leadership in the early battles of the Seven Years’ War amply confirmed Frederick’s judgment. In late 1758 Keith was recovering from a breakdown in his health.

On October 10 Frederick’s 37,000 troops encamped at Hochkirch in Saxony. The substantial village was situated on a low rise that commanded the surrounding plain. Looming over the cluster of cottages, cabbage gardens, and narrow lanes was a new church, one rather surprisingly grand in scale and style compared to the modest village. By the church was a large cemetery surrounded by a sturdy stone wall. Many local inhabitants were Wends, people of Slavic ancestry whose language is reflected in some Saxon place names.

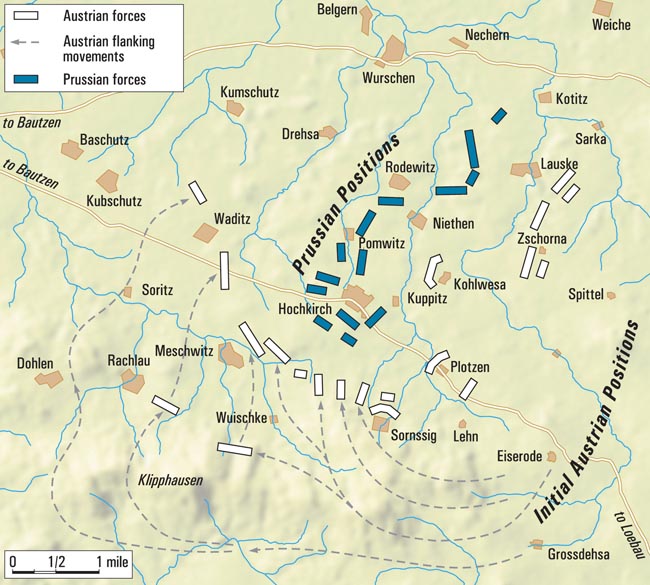

The Prussians erected a redoubt to shield the southern approaches to the village. The redoubt bristled with 20 12-pounder cannons and half a dozen smaller guns. Some battle accounts refer to this field work, which rested on a rise slightly higher than Hochkirch, as the Grand Battery. Grenadiers in smaller nearby works protected the flanks of the artillery position. The Prussian forces were deployed on a three-mile front from Hochkirch to Rodewitz. From his new camp, the king planned to strike the nearby Austrians and drive them out of Saxony.

Frederick’s army, though, was in a precarious position. Although the site of Hochkirch itself provided a good field of fire, it overlooked only a rather narrow stretch of pastures and hayfields. These sunlit fields quickly ended in barriers of dark woods covering hills to the south and east that rose much higher than the village. The hills and forests offered cover to potential enemy attacks.

With his experienced eye for terrain, Frederick noted that a hill known as the Stromberg, which was located two miles from the Prussian left at Rodewitz, was a key position. The Prussian king believed that by holding the Stromberg his troops would be able to menace Daun’s right flank and compel the Austrians to withdraw. Conversely, if the Austrians held that hill, Frederick’s own position would be in danger. To ensure that the Stromberg was in Prussian hands, Frederick ordered Lt. Gen. Wolf Frederick von Retzow to secure the important hill.

The Austrians, though, had already occupied the hill. When he approached the Stromberg, Retzow found Austrian troops swarming over it. Certain that an attack would be costly and futile, the general did not act on the king’s orders. Under the impression that the Stromberg was lightly held, the king again ordered Retzow to attack the hill. Frederick’s initial assessment had been correct, as at first only a small force held the hill. While Retzow hesitated, however, Daun dispatched a substantial infantry and artillery force to occupy the strategic hilltop. When Retzow declined a second order to attack, Frederick became enraged. Despite the angry king’s stipulation that his head would be forfeit if he failed to move, Retzow’s forebodings were so strong that he submitted to arrest and gave up his sword rather than give the order to assault the position.

Besides the Stromberg, the Austrians also held two thickly forested hills south of Hochkirch. One was the Kuppritzerberg, and the other farther to the southwest was the much larger Czarnabog. The latter hill’s name, drawn from the Wendish language, meant “Devil’s Hill.” The name aptly symbolized the menace of the dark forests hiding enemy movements around Hochkirch. Not only did the much larger enemy force control the higher ground overlooking it, but Frederick’s troops were stretched thin. Indeed, the Prussian line was too long for a successful defense. What is more, a dangerous gap of about two miles separated the Prussian troops at Rodewitz from Retzow’s 9,000 men who were deployed at the village of Weissenberg.

The Prussian king was well aware of the potential risks of staying at Hochkirch. But with strong faith in his own military ability and deep contempt for his enemies, Frederick would not make a quick withdrawal to a safer camp. Keith saw that their camp was within artillery range of an enemy holding the Stromberg as well as other high pieces of ground in their front. “If the Austrians leave us alone here, they deserve to be hanged,” Keith warned the king. “It is to be hoped that they are more afraid of us than of the gallows,” replied Frederick.

Up to that point, the Austrian strategy had been strictly one of defense. Daun was often called “Fabius Cunctator” after Roman dictator Quintus Fabius Maximus Verrucosus, an opponent of Hannibal who used delaying tactics rather than direct attacks on the legendary Carthaginian commander.

During the campaign, offensive moves by the Austrians had been so rare that Frederick never expected Daun to roll the dice and launch a surprise attack. The Prussian king therefore waited for his supply train, and the armies seemed to settle more or less quietly into their lines. The big guns of the Grand Battery, aimed at the menacing wooded hills, remained silent. Little broke the dull daily routine other than the Croatian pandours of Daun’s army.

The pandours were irregulars from Croatia and the Balkans. Instead of military uniforms, they wore their regional clothing, which resembled the dress of the Ottoman Empire. Each one typically carried a saber, a dagger, and one or more pistols. They harassed communication lines, killing or capturing couriers, or fell on isolated detachments and baggage trains. Regular officers looked down on them as wild and undisciplined, considering them more like bandits than soldiers; indeed, they had a notorious reputation for looting. Nevertheless, the pandours were tolerated for their superb skills as woodland fighters and guerrillas.

The pandours controlled large stretches of forests and woods around Hochkirch in front of the Austrian lines. They lurked near the Prussian camps, often hitting them before dawn and then disappearing into the mist-filled woods. Since the attacks were mere pinpricks compared to the massive scale of the campaign in Saxony, officers who were any distance away from the dawn raids paid no attention to them.

In the Prussian camp, Army chaplain Carl Daniel Kuster fretted about his clammy tent staked on the cold, wet ground. Worried that he would be unable to preach if his damp and chilly quarters made him sick enough to lose his voice, he left his tent and paced up and down by the Grand Battery. A sympathetic officer offered him a place to sleep in a shed near the redoubt. From his new vantage point, Kuster saw to his dismay that they seemed to be very close to the enemy. Changing his mind, the chaplain walked to the village and accepted the offer of a cot in a farmhouse occupied by a Captain Kotulinsky and his infantry company.

On the night of October 13, 1758, Frederick and his officers watched a vast stretch of glowing campfires from the enemy positions. As Kuster learned, some stretches of the opposing lines were a half mile away, close enough that one could hear Austrian soldiers talking or singing. It sounded as if the enemy had no inkling that the Prussians were ready to attack the next day.

Far from lazing unaware of Frederick’s intentions, the Austrians were lining up for an assault before first light. Lt. Gen. Franz Maurice von Lacy persuaded his cautious commander that this was a perfect time to hit the unsuspecting Prussians.

The sounds and lights seen by the Prussians that night were all a ruse. Practically everyone was gone, leaving a small number of troops to put on a performance. Officers barked orders to nonexistent units. Soldiers wandered amid the empty tents all night, stoking campfires while singing and talking loudly enough for the sound to carry to the enemy. Work parties made as much racket as possible, chopping trees and branches by lantern light, giving the impression that Daun was settling deeper into the abatis surrounding his camp.

The rest of Daun’s army slipped toward the right flank and front of the enemy position. Covered by darkness and the pandours, on previous nights Austrian pioneers had cut roads through the woods in preparation for the surprise attack of October 14. The noise of chopping and singing from the vacant camps covered the sounds of marching feet, clopping hoof beats, and creaking wheels edging toward the staging points for the attack.

Well before dawn, the Austrians loomed near the mist-shrouded Prussian camp. Daun and about 30,000 men marched over the Kuppritzerberg, poised to fall on Hochkirch from the south. To Daun’s left, Lt. Gen. Ernst Gideon von Laudon aimed at the Prussian right from the southeast. A Latvian-born Austrian commander, Laudon claimed kinship with the Scottish earls of Loudoun.

Farther past Daun’s left, a cavalry force under Lt. Gen. Count Karl O’Donnell (a member of a family of Irish exiles) rode down the road from Steindorfel, placing it on a direct course to the rear of the Prussian right. Lt. Gen. Charles Marie Raymond d’Arenberg led 20,000 to Daun’s right, aimed at the Prussian left. To keep Retzow’s troops separated from the rest of their army, the Prince of Baden-Durloch and 16,000 men would attack him at Weissenburg.

The fog and the pandours both worked to screen Daun’s maneuvers from the Prussian sentries. Nothing was seen of the Austrians until several chosen men, pretending to be deserters, trickled into the Prussian picket posts and surrendered. But more and more Austrian “deserters” appeared; enough of them gathered to outnumber the men assigned to guard the outposts.

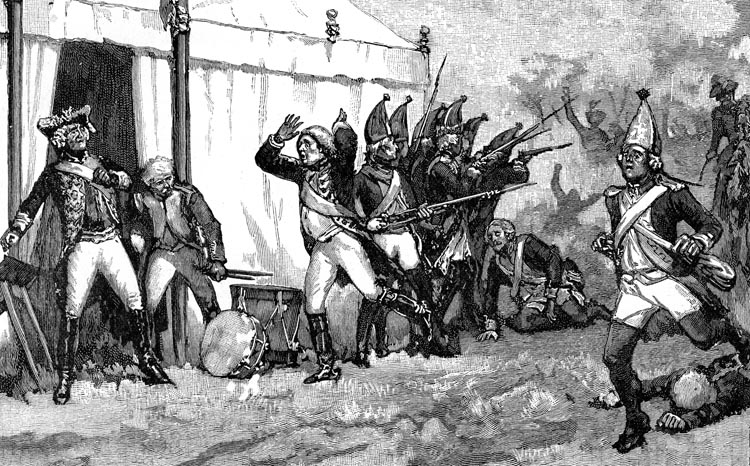

At 5 am the village clock of Hochkirch struck the hour. When the fifth and final chime echoed away, the Austrian pickets near Rachlau fired a volley. Mistaken by the Prussians as a pandour raid, these shots were the signal to spring Daun’s trap. Confident of their king’s preparations and strategy, most of Frederick’s men had gone to sleep without any particular worries. The attack was a stunning surprise. Hardly had the village clock struck when the Austrian deserters overwhelmed the picket posts in front of the camps. Captured cannons were turned around to fire into the Prussian tents and moments later Daun’s foot soldiers came at the Prussians with musket fire and bayonets.

Georg Friedrich von Tempelhof, later a noted artillerist and mathematician, was a young subaltern in charge of a pair of 24-pounders supporting a battalion of infantry. Awake at 3 am, Tempelhof stood by a watch fire, expecting the customary threat of the pandours and wondering, in his words, “what form it would take this morning.” By 5 am, Tempelhof was almost disappointed. There was “not a mouse stirring,” he recollected. It seemed to the subaltern that there would be no pandour activity.

When the first musket shots rattled in the misty darkness, Chaplain Kuster awoke. At first, he thought it was only another attack by the pandours. He awoke Captain Kotulinsky, who also agreed that the outbreak of gunfire meant nothing but still thought it best to turn out his men just in case.

Outside, foot soldiers formed on either side of Tempelhof’s guns. Tempelhof knew by then that this was no mere escapade of the pandours. He ordered his guns to fire into the darkness “to learn whether there was anything in front of us,” he wrote. For a few minutes, there was nothing but “mere crackery,” taken to be scattered shots exchanged with pandours. But the firing grew louder as the enemy drew nearer. The 24-pounders and the infantry fired into a mass of enemy troops perhaps 200 yards away. After his guns fired about 15 rounds, the young officer fell unconscious to the ground.

When Tempelhof came to, he felt blood running down his face and thought he had been shot. He drew himself onto his hands and knees and saw that he was surrounded by “Austrian grenadiers, who had crept in through our tents to the rear.” One of them had slammed him in the head with a musket butt.

It was still dark, and Tempelhof got only brief glimpses of the action from the glare of the watch fires and the flashes of muskets. The opposing forces were so thickly crowded and desperately pressed that “they did not fire much, having no room, but smashed and stabbed and cut.” Austrian troops took the dazed subaltern prisoner, but Tempelhof was freed when Prussian cavalry cut its way into the fighting.

After Kuster left the farmhouse, he joined Kotulinsky, who had his men in line. The chaplain felt the ground shake as the big guns roared in the Grand Battery. “The howitzer shells fell like hailstones,” recalled Kuster. As the armies rushed together, the opposing forces were so close that orders shouted by Prussian and Austrian officers in their shared language were getting mixed up by the soldiers. There was only enough light that the soldiers could distinguish friend from foe by grabbing their hats, the metal plates of the Prussian headgear setting them apart from the Austrian hats.

Meanwhile, Frederick was at his headquarters at Rodewitz, about two miles northeast of the church at Hochkirch. Sounds of cannon blasts and musket fire easily carried to the king’s quarters. Signal rockets traced brightly colored alarms into the skies.

Among the soldiers there was a young ensign, Ernst von Barsewisch of the Wedel Regiment. Barsewisch’s commanding officer, suspecting trouble, had ordered his men to sleep in their uniforms to be ready at a moment’s notice. Scattered musket shots awoke some of the men, and they stepped out of their tents to investigate. As the firing quickly intensified, the officers ordered the men into line.

For some time, though, the king refused to believe the cannons and rockets signified anything more than irritating noise. He turned to Barsewisch’s regiment and asked, “What are you about, lads? It is nothing—only those scoundrels the Croats.”

Just as the king ordered the men back to their tents, an aide arrived with disastrous news. Captain Karl Ludwig von Troschke warned that the redoubt south of the village had fallen and that the Austrian artillery would soon be within range of Rodewitz. Frederick still did not believe the aide until enemy artillery rounds soared over their heads. “Troschke, you are right!” said the king. Turning to his soldiers, he ordered, “Men, get your muskets!” He immediately pushed himself to action, ordering his men into line and sending for his horse.

Marshal Keith already was riding toward the rising sound of battle. He was lodged with Duke Frederick Francis of Brunswick-Wolfenbuttel, a brother-in-law of Frederick, in a nearby chateau owned by a major in the Saxon Army. “At the first alarm in the night, he mounted his horse, assembled a body of troops … and marched directly to the place that was being attacked,” wrote a correspondent of The Gentleman’s Magazine. When Keith learned that the enemy had overrun the Great Battery south of the village, he set out to recapture the pieces. He sent a courier to the king, promising to hold on until the last man. The Scotsman then gathered enough fragments of broken battalions to retake the battery, but there were too many Austrians on hand for his scratch force to hold on. Keith had to abandon his prize and withdraw to rally troops for another attempt.

Riding with the marshal was an English soldier, who in contemporary sources was identified as John Tebay. According to Samuel Johnson’s biographer James Boswell, Tebay was none other than British Lt. Gen. James Oglethorpe. Most famous as the founder of the American colony of Georgia in 1733, Oglethorpe also had a long military career. His prospects blighted by a court-martial and the enmity of King George II, Oglethorpe spent several years as a wandering exile in Europe.

Whoever Tebay was, the details of his experience in the battle reached the British press. Tebay stated that Keith’s aides deserted him, leaving the marshal escorted only by Tebay and a footman. Keith smashed his way into Hochkirch three times, only to be repulsed by greater numbers of enemy troops. While leading another attack to retake the Grand Battery, Marshal Keith was shot twice. Remaining in the saddle, he directed his troops until he was instantly killed by a cannon ball. Tebay caught the marshal as he fell from his horse. Keith’s horse was shot twice but survived; Tebay’s mount was hit five times.

Foot soldiers from fractured Prussian units packed the village of Hochkirch. One street was jammed with soldiers squeezed so tightly together that the dead were held upright by the pressure of their comrades. Blood poured from the packed bodies and flowed as if the lane were the channel of a stream. So many men died there that the lane was named Blutgasse, meaning Blood Street.

Near the Blutgasse, a Lieutenant von Marwitz of the regiment of Margrave Carl of Brandenburg-Schwedt held the church cemetery with a small detachment. After he was shot in the chest, the lieutenant leaned on the stone wall to hold himself up while he directed the defense of the churchyard. More men of the battalion, under the command of Major Simon Maurice von Langen, reached the churchyard and fired into the Austrians.

From the north, Prussian reinforcements pushed into the burning village of Hochkirch. Prince Francis led three regiments of infantry into the battle. To support this attack, Field Marshal Prince Maurice of Anhalt-Dessau rallied as many troops as he could and followed.

The two princes cut their way into Hochkirch. For a short time they gave Langen’s men in the churchyard a few moments of relief. From the south, Austrian gunners in the Grand Battery poured shot and canister into the village.

In the hazy, dim light, the nearsighted Prince Maurice nearly rode into the enemy lines. He realized the troops near him were the enemy and was shot as he rode away from them. Before he could rejoin his troops, the prince was captured.

A cannon ball decapitated Prince Francis. Wild with panic, his fine light gray horse bolted. Galloping madly, it first dashed toward the Austrians then back to the Prussians.

Pressure on Hochkirch mounted as the Croats attacked from the left, and General Lacy threw in his cavalry. Major Langen’s defense of the churchyard spurred desperate attacks by the enemy to clear the last Prussian stronghold in the village. Eventually, Langen faced seven Austrian regiments. An Austrian officer, Captain Jacob Cogniazo, compared the stubborn regiment of the Margrave Carl as a dam holding back the flood of troops trying to capture Hochkirch. Indeed, Langen’s tenacious stand tied up thousands of men who might have been better employed in sweeping away the fragments of Frederick’s battered army.

Langen saw his ammunition dwindling away, and his support was falling back to the north. Holding on any longer was impossible. “My children, we must dash through them,” ordered the major. Bayonets lifted, they charged out through the back gate of the churchyard while the enemy fired into them. All but a few of the churchyard’s “garrison” were killed or captured. Wounded by 11 musket balls, Langen fell and was taken prisoner. He died one week later.

By 6 am Hochkirch was lost for good for the Prussians. Flames rose from thatched roofs and wooden buildings, and the ruined village was a burning beacon visible for miles in the dim light of early dawn. Frederick’s troops pulled back and formed a line at Pomeritz, about one mile north of Hochkirch.

Earlier that morning, Barsewisch’s hat was shot through twice by enemy musket balls. Three officers, including two brothers named Hertzberg, were with him when the second shot knocked the hat to the ground. Barsewisch joked about how much the Austrians seemed to like his hat. Then, the elder Hertzberg brother produced a snuffbox and teased that they could all do with a pinch of courage. After three of the officers took snuff, the elder Hertzberg was about to take his turn when a musket ball struck him through the forehead. Hertzberg gasped, “Lord Jesus” and fell dead.

The trees and growth on the higher ground near the Prussians gave the Austrians excellent cover. Veterans remembered the enemy fire was intense and accurate, often shooting soldiers in the upper body or head, as they did with Hertzberg. Frederick was so intent on watching the action that he seemed surprised when an officer warned him that his horse was bleeding. Indeed, the king’s mount, a fine brown horse from England, had been hit several times. Soon after the monarch changed mounts, the English horse collapsed and died.

Barsewisch’s company lost man after man until it dwindled down to a small remnant. His company commander and battalion major fell, leaving the young ensign as the only officer among a handful of men. Their ammunition running low, and Austrian cavalry preparing to overrun them, Barsewisch resolved to save their three stands of colors.

Enemy cavalrymen spotted the flags and gave chase. Barsewisch’s hat, which had already been pierced by two bullets, was lost for good when an Austrian cuirassier hacked at him with his saber. The Austrian’s saber knocked off the ensign’s hat. Luckily for Barsewisch, the saber slash sent the hat spinning up into the air and spooked the cavalryman’s horse, enabling him to escape. Shortly thereafter, Barsewisch took off his bright new sash and hurled it at two pursing enemy horsemen. Tempted by the sash, the riders stopped and one of them dismounted to pick it up, allowing the Prussians to escape with their colors.

By 10 am, the fighting ebbed. Prussian foot and horse soldiers made their way to join Frederick at a new defensive line formed at Pomeritz. Among them were Barsewisch’s little band with their banners. But nearly all of their artillery was captured or abandoned during the morning’s disastrous fighting. Retreat was the only option, and the king ordered a withdrawal. Troops from the left, first a few battalions and then several thousand of General von Retzow’s men, guarded the rear.

The army flowed across a stone bridge that came under heavy fire from the Austrian artillery. Fortunately, the sturdily built bridge held. Daun’s army, disorganized and worn by the night’s marching and the intense battle, made no effort to pursue their enemy. Frederick managed to get away with a loss of nearly 10,000 men killed, wounded, or captured. Also left on the field were 101 pieces of artillery and most of the army’s tents, supplies, and baggage. Daun lost 7,500 men.

Keith’s body was found by looters who stripped him of his possessions, even his clothing, and left him covered only with a Croatian cloak. With other anonymous dead soldiers, Frederick’s field marshal was laid out in the church in Hochkirch. Marshal Daun, with General Lacy and other high-ranking officers, entered the church. Lacy noticed a large and distinctive scar on the leg of one of the dead. In shock, he broke down and wept after exclaiming, “It is my father’s best friend!” Growing up in a family of Jacobite exiles in Russia, Lacy had long known and admired Keith as a fellow exile and a dear friend of his father. Fate taking them into different armies, they had not seen each other in years. The next day, Keith was buried in the churchyard. Lacy and other commanders attended the funeral, and they gave their fallen enemy the tribute of two 12-gun salutes.

Carts filled with Prussian wounded bumped over the country roads leading away from the battlefield. There was not enough straw for padding, so the wounded were slammed about the wooden floorboards. Neither were there enough carts, and badly wounded men plodded along on foot until someone died and opened a space for them. Teamsters halted their carts again and again so dead patients could be buried. Quarrels broke out over the dead men’s shoes and shirts. A few such as Chaplain Kuster wanted the dead buried with their shirts. Many soldiers needed shirts of their own, while others sought to tear the shirts of the dead into bandages, as there was no other cloth available.

King Frederick, while not particularly close to his slain brother-in-law Prince Francis, was shattered by Keith’s death. Prince Maurice would never recover enough to take the field again; he would die of cancer the next year. Two other talented Prussian generals, Hans Caspar von Karnow and Karl von Geist, were mortally wounded.

A worse tragedy was in store for the king. While the battle was raging at Hochkirch on the morning of October 14, his beloved older sister, Margravine of Brandenburg-Bayreuth Wilhelmine, died. Three days later, the news reached him, plunging Frederick into despair. He had a long conversation with his secretary Henri Catt, in which the king showed him a pillbox hanging around his neck. Inside were opium pills, which the king would have taken in the event of his capture.

After such a defeat, it was necessary for Frederick to project confidence to his army. His soldiers passed around the king’s post-battle remarks. “My dear Goltz, they did not wake us up very politely,” Frederick said jokingly to Maj. Gen. Karl Christof von der Goltz.

Daun’s gamble on a surprise attack indeed paid off in a victory, but he soon frittered away any advantage gained by the battle. An aggressive pursuit of Frederick’s battered and outnumbered army had at least the potential of knocking Prussia out of the war, but Daun resumed his cautious strategy once again. There were a few minor clashes, and Daun laid siege to Dresden. But Frederick marched his army to relieve the city, and the Austrians withdrew. The armies settled into their winter quarters.

Frederick the Great’s defeat at Hochkirch was all the worse for being an unnecessary battle, brought on by his stubborn refusal to seek a less dangerous and exposed position in front of an army twice the size of his own. After Frederick had been caught by surprise, he aggravated his disadvantages by not taking the attack seriously during the early stages of the battle.

Major General Antoine-Marie de Malvin Comte de Montazet, the French attaché serving with Daun, dismissed the idea of condemning his talented enemy. De Montazet was impressed by the way Frederick molded his army into a force that could withstand anything, even his own flaws.

“It is very easy to criticize him,” wrote De Montazet. The French attaché noted that even though Frederick was surprised and beaten at Hochkirch and lost all of his artillery, his army nevertheless made “the finest of retreats,” having halted just four miles from the battlefield. De Montazet marveled that Frederick’s army went over to the offensive just four days after his defeat. The Prussian king “has an army which permits him fault after fault, because it is always ready to retrieve a reverse,” De Montazet noted with unabashed admiration.