By David H. Lippman

For once, the ULTRA message came late. Normally, the decoding machines and hard-working British cryptographers at Bletchley Park had an abundance of German Army messages to go through, but in the first days in August 1944, the German panzer divisions had gone to radio silence, which suggested they were going to attack, but not in which direction.

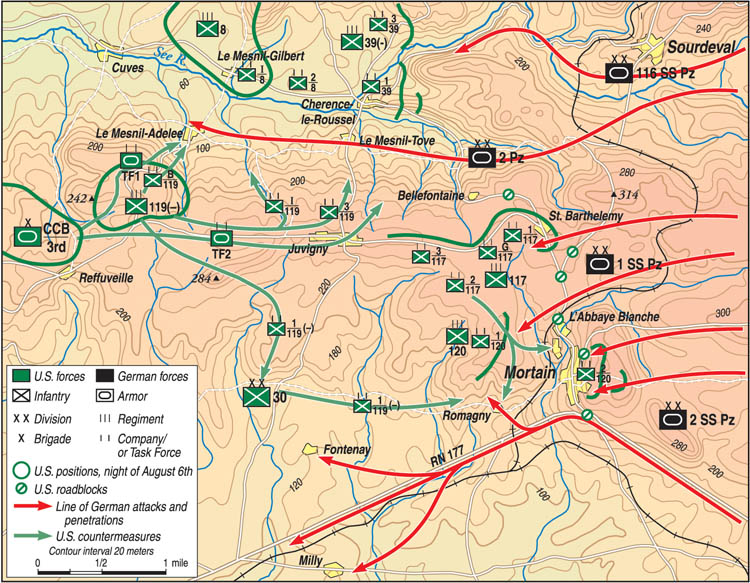

Then the Germans gave away the game. On August 6, the 2nd Panzer Division broke radio silence and asked for night fighter support to back the attack that evening over an area from St. Clement to St. Hilaire and for more fighters later that day. A followup message said that the 2nd SS Panzer Division “Das Reich” would drive west at 8:30 pm toward Mortain and would need Luftwaffe bombers to suppress American artillery before them.

As soon as the message was decoded, Bletchley dispatched the warning to Lt. Gen. Omar N. Bradley, commanding the U.S. 12th Army Group, which would face this offensive in France. The result was twofold. By 4 am on August 7, Bradley and his senior commanders had a complete picture of the German counterattack, codenamed Operation Lüttich. Second, the full picture did not matter anyway. The defending Americans were already feeling the first impact of Adolf Hitler’s latest blitzkrieg, the only one he would launch in Normandy. It was a misguided operation that was doomed to catastrophe.

Operation Lüttich was born in the military chaos of Germany’s defeat in the American Operation Cobra, the breakout from the Normandy beachhead, in July and the political chaos of the botched German attempt on Hitler’s life that same month. Hitler, suffering from serious physical injuries and mental trauma from a bomb going off near his feet, was facing disaster on both the battlefield and the diplomatic front. Soviet troops were driving into Poland and the Balkans. German puppet states were seeking a way out of the war. German domestic morale was sinking under heavy bombing and heavier casualties.

The latest blows had started coming with the Allied invasion of Normandy on June 6. British and Canadian troops defeated German panzers in attritional battles near Caen in the east, while American mechanized forces under the hard-driving Lt. Gen. George S. Patton blasted a hole through German lines at Coutances in the west and stormed down French roads, driving both west into Brittany and east toward Argentan to surround the German Seventh Army. If Patton from the south and the British from the north bagged the Seventh Army, the German defenses in France would collapse, and some of the toughest panzer divisions—nearly impossible to replace at this point—would be lost.

To prevent this, Hitler ordered his favorite response to an enemy offensive: a massive panzer counterattack to halt the American drive by cutting off its supply lines, making Patton vulnerable to isolation and destruction.

Hitler’s plan was bold, calling for Seventh Army, under SS Lt. Gen. Paul Hausser, to hurl four panzer divisions, two of them elite SS outfits, and an SS panzergrenadier division at the thin center of the American line and drive on the road junction town of Avranches where Normandy met Brittany, cut all the roads, and strangle American supply lines. The plan was named “Lüttich” in honor of the German name for the Belgian city of Liege, which Kaiser Wilhelm II’s men had captured 30 years ago almost to the very day, setting up an offensive that drove the French back to Paris.

The only problem in Hitler’s grand theory came from the very generals he was assigning to carry out this mission. The German officers who attempted to assassinate Hitler and end the war had barely missed their target—the Gestapo’s vengeance did not. More than 5,000 German officers, some as high as the rank of field marshal, were arrested and subjected to hideous show trials and ghastly torture.

Among those under the Gestapo’s eye was the top German commander in the West, Field Marshal Gunther von Kluge, known in the Army as “Clever Hans,” a play on his name as “clever” in German is “kluge.” He was suspected of promising the plotters to make use of his high rank and position to be the peace emissary to the British and Americans.

Nonetheless, Kluge was the man in charge and on the spot, and he would have to lead the assault. Problem was, Kluge did not have much to work with. The Seventh Army in particular was a disaster. Most German transport consisted of horse, bicycle, and foot. Most German panzer divisions had been ground down by ceaseless attrition from Allied fighter bombers and Allied tanks, losing 750 of the 1,400 committed to battle. The constant bombing had also wrecked German supply lines and morale. Weakened supply lines meant few replacements, and cooks, bakers, and other paper chasers were put in the front as infantry, failing miserably. Luftwaffe pilots taking to the sky found themselves jumped by vast numbers of British Supermarine Spitfire and U.S. North American P-51 Mustang fighters. Tension between the Nazi extremist (and better equipped) Waffen SS and the Wehrmacht was intense, even though both endured the same combat nightmares.

No matter. On July 31, Hitler ordered Deputy Chief of Staff General Walter Warlimont to go personally to Kluge’s headquarters at the Duke de la Rouchefoucauld’s palace at La Roche-Guyon in France and brief Kluge on the plan.

Acting as Hitler’s personal eyes and ears at Kluge’s headquarters, Warlimont arrived on August 2 to find that the situation was disintegrating. Kluge had planned a counterattack himself but nixed it because of Patton’s advance to the east, south of Mortain. The American 79th Infantry Division was headed for Laval, while the 90th Infantry was driving on Mayenne. East of the planned Mortain attack area, Lt. Gen. Courtney Hodges was advancing with his U.S. 1st Army, and VII Corps commander Lt. Gen. J. Lawton Collins ordered Maj. Gen. Clarence Huebner’s 1st Infantry Division to seize the city and a dominant feature above it called Hill 314. The hill was a tourist attraction for hikers, who enjoyed the outcroppings that led to an 18-mile view in all directions, as far as Avranches to the west. Reminded to seize the high ground, the laconic Huebner said, “Joe, I already have it.”

With that, Collins decided to replace the 1st Infantry, veterans of North Africa, Sicily, and D-Day, with the 30th Infantry Division, which would hold the area while the “Big Red One” headed for Mayenne.

The 30th “Old Hickory” Infantry Division was a National Guard unit, its men drawn from North Carolina, South Carolina, and Tennessee. Commanded by Maj. Gen. Leland Hobbs, the division’s three regiments were descendants of Confederate battalions that had fought at Gettysburg and Cold Harbor. More importantly, the 30th had endured harsh fighting in the Cobra breakout, even being bombed by mistake by the U.S. Eighth Air Force.

Now, after watching a USO show with Edward G. Robinson, the Tennesseeans and Carolinians began replacing the “Big Red One” in its positions east and north of Mortain, an unremarkable town of 1,300 people whose main point of interest was that it sat at the center of a spider’s web of roads. The division’s 117th Infantry Regiment took over defending the village of St. Barthélémy, a small town north of Mortain. The 120th took over Hill 314 and the other nearby crests, while the 119th was put in reserve. The 120th’s commander, Colonel Hammond Birks, said to his aide-de-camp, “This town is ‘wide-open.’ The hotels are full. It should be an excellent place for a little rest and relaxation.”

But an outgoing 1st Infantry officer warned Birks, “Hill 314 is the key to the whole area. In case of emergency this hill has to be held at all costs.” Birks assigned that task to his 2nd Battalion under Lt. Col. Eads Hardaway, telling Hardaway, “If any trouble develops, it will be from that direction. Put roadblocks on all approaches to the 2nd Battalion position.” The Americans did so but found other problems. The 1st Infantry Division’s positions were poorly prepared. Some foxholes were only 18 inches deep. The phone net had to be rewired, and there was no time to deploy minefields.

Meanwhile, German troops and tanks converged on their lines of departure, doing so by night to avoid Allied fighter bombers. Even so, things went wrong. The XLVII Panzer Corps commander General Hans von Funck disliked his SS boss, Hausser, and the two did not work well together. Nor did Funck get along with the 116th Panzer Division’s commander, Lt. Gen. Gerhard Graf von Schwerin. The 2nd Panzer and 1st and 2nd SS Panzer Divisions fielded only 75 Mark IV tanks, 70 Mark V Panther tanks, and 32 self-propelled guns, combined.

The 2nd Panzer was assigned to the right, 2nd SS Panzer and 17th SS Panzergrenadier to the left, and 1st SS Panzer to the center. The 116th Panzer Division, on the extreme right, would join the attack as soon as it could. The 1st SS Panzer’s move-up was delayed when a British Hawker Typhoon fighter bomber crashed into the leading tank in a narrow lane, holding up an entire column. It took the division all morning on the 6th to get sorted out.

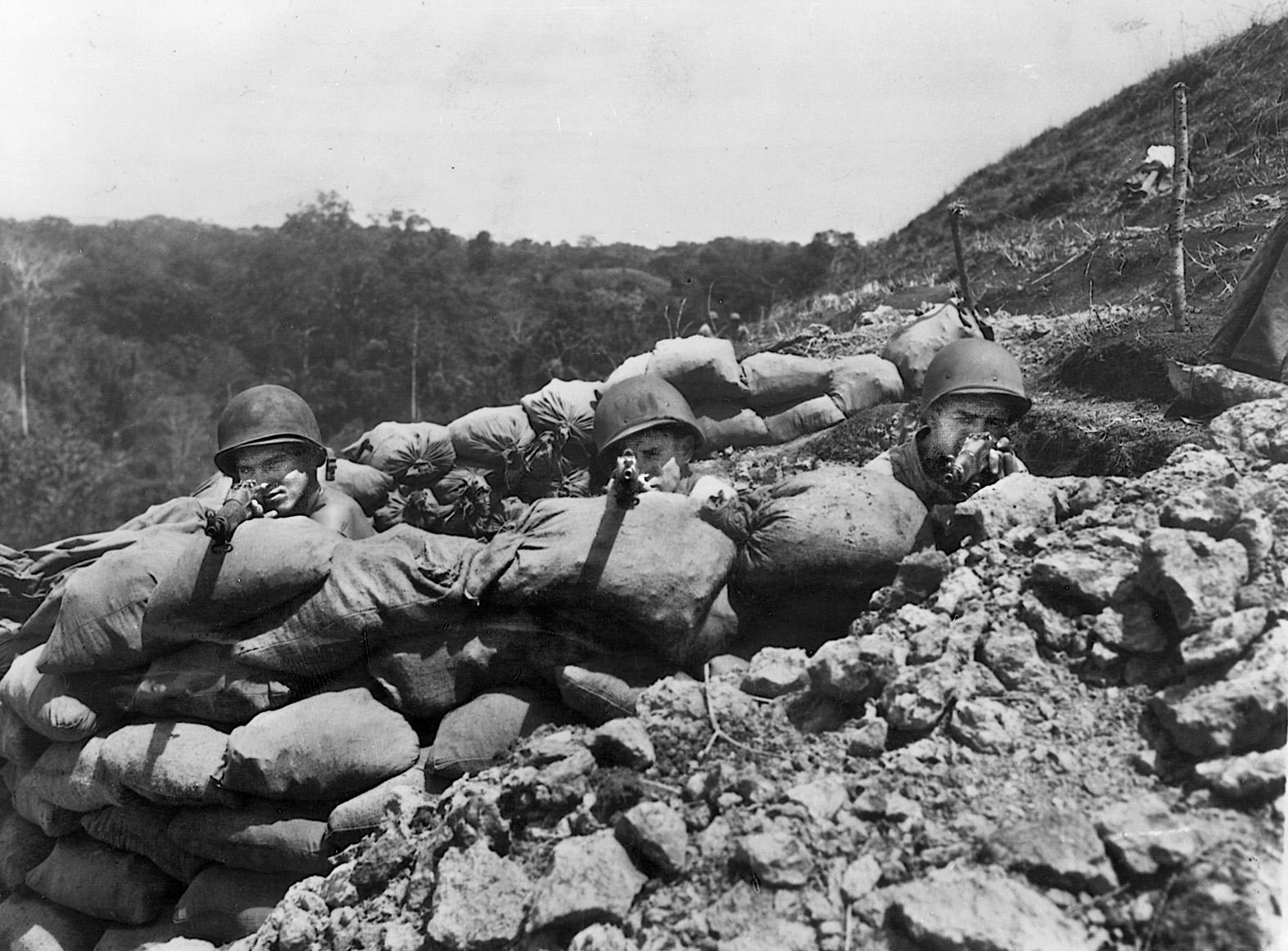

Nonetheless, at 2 am on August 7, Lüttich got down to business in the dark and predawn fog with a German panzer assault in best blitzkrieg style against the 30th Infantry Division. To preserve surprise, the Germans did not precede the attack with an artillery barrage. The Germans planned to surround Mortain and cut it off, trapping the American 120th Infantry from behind. Using infiltration tactics in some places and SS ferocity in others, the attack went in. An SS battle group, Kampfgruppe Fick, attacked Hill 314 head-on, yelling “Heil Hitler” as they charged under supporting machine-gun fire. G Company of the 120th answered back with furious fire, holding them off, but the Germans overran H Company’s headquarters. More German troops attacked the 2nd Battalion of the 120th Regiment, forcing Birks to commit his reserve, C Company, to help hold Mortain and Hill 314. The 2nd/120th and one company of the 3rd/120th would ultimately defend the ground.

Meanwhile in Mortain, Hardaway set up his headquarters team to defend the HQ in the Hotel de la Poste. Even the radiomen had to abandon their sets and grab their rifles. Sergeant Robert Bondurant, manning the switchboard, told Birks about the crisis.

“Hold the town at all costs,” Birks ordered. ‘Stay at your post.” Bondurant did so.

As a misty dawn approached, the Germans started shelling Mortain. GIs in foxholes in the cemetery north of town saw blasts explode lids off crypts and topple headstones. C Company moved forward and battled SS men in the dark.

The 2nd SS Panzer’s drive was led by two Frenchmen whose sympathies were with Hitler. They headed toward a roadblock held by A/120th, where three GIs challenged the Frenchmen. The traitors explained that they were guiding a “lost” vehicle back to American lines. During the palaver, a German machine-gun crew worked its way into a field behind the fence. Once there, it opened fire, killing the Americans. The rest of the Americans killed the French traitors, but the damage had been done—German machine gunners opened up on the roadblock, and the tanks overran it, surging through A Company and heading for B Company.

The B/120th command team saw the Germans coming, and First Sergeant Reginald Maybe handed a bazooka to his company commander, Lieutenant Murray Pulver, who promptly crouched behind a stone wall and fired on a Mark IV from 10 yards away. The round hit the tank’s turret, rocking it to a stop. The engine kept turning over, but the blast killed or wounded everyone in the tank. The SS did not give up, though. A dozen SS troopers charged up yelling, “Amerikaner Kamerad,” calling upon them to surrender. Pulver fired his carbine at the attackers, and his men did the same, dropping most of the Germans to the ground. The Americans suffered no casualties, but Pulver figured he could not hold much longer and pulled back. He had gained time for B/120th to establish a new defensive line.

Through the fog, the German advance continued, now backed by artillery, including their Nebelwerfer rockets, known to Americans as “Screaming Meemies” for their terrifying sound. German tanks and infantry drove into Mortain itself. One group of SS men charged into a battery belonging to the 197th Field Artillery and drove off in a jeep with a radio, map, and coding machine. A panzer shot up trucks and cooked off ammunition before retiring, its crew fearful of American bazooka teams taking advantage of the fog to blast rounds into the sides of German tanks.

Gradually, the Germans took control of Mortain in heavy fighting, clearing the buildings of straggling Americans. In his HQ, 2/120th’s commander, Colonel Hardaway, warned Birks that he would have to temporarily shut down operations. SS men were inspecting wrecked American vehicles outside his building. SS men yanked wounded American soldiers out of damaged buildings and made the prisoners sit in the middle of a road—the GIs feared the SS men would massacre them as they had done to hundreds of French civilians in Oradour-sur-Glane. Sergeant Robert Bondurant, who manned his telephone switchboard to the last, recalled, “I thought they were going to shoot us. Instead they walked us back to an aid station. Wounded were lying around everywhere, both German and American.”

Meanwhile, much of the 2/120th was still holding on to Hill 214, not yet aware that they were being surrounded. They were facing attacks by a determined SS trooper armed with a flamethrower. One American killed the flamethrower man, but the Americans could not silence the enemy artillery. Worse, the Americans were short on supplies and ammunition, and supporting artillery could not find targets in the mist.

One of the last Americans to reach the hill’s summit was Captain Delmont Bym, leading H Company, the heavy weapons outfit. Bym was stunned by the sight of wounded men lying everywhere. “It was my first week of combat,” he said later. “I was kind of shocked to see injured men lying there in the open, being hit by shrapnel.”

With Hardaway and his command team gone, leadership of the 2nd/120th fell on Captain Reynold Erichson, who headed F Company. He moved quickly, rounding up about 40 stragglers and pulling all the companies into an all-round defensive position on the summit, fully aware that his 600 men were facing one of Germany’s top SS panzer divisions, which mustered at least 9,000 men.

Erichson was a 24-year-old peacetime Iowa farmer, and three of his four company commanders had never led companies in battle. However, Erichson had one trump card: two forward artillery observation officers (FOOs), the eyes of 30th Division’s heavy guns. From their hilltop observation posts, Lieutenant Robert Weiss and Lieutenant Charles Bartz had a grandstand view of the entire countryside as the fog burned off and a battery-powered radio to call down targets for the 230th Field Artillery Battalion’s guns.

Northwest of Mortain, the 1st/117th Infantry Regiment, under Lt. Col. Robert Frankland, faced the 2nd Panzer Division’s tanks. The odds were against the 117th. A Company, for example, had a brand new lieutenant commanding it, and its 3rd Platoon had no officers. The company lacked bazookas and artillery support but did have 55 newly arrived replacements.

The 2nd Panzer Division’s Panther tanks hit the 117th from three directions at St. Barthélémy, slamming into the 823rd Tank Destroyer’s antitank and tank-destroyer guns. Lieutenant George Greene, brand new to the battalion, led the men, blasting open German tanks and firing off an entire clip of machine-gun ammunition to give his men a chance to escape the enemy. After vicious fighting, two German tanks drove within 250 yards of Birks’ command post.

The 117th fought hard—their guns and bazookas taking down German infantry and tanks— but German advantages in trained men and heavy tanks soon told. A Company was wiped out in minutes with only one officer and 27 men escaping death or capture.

At midmorning the Germans attacked again, some in captured GI jackets to confuse the defenders, and finally drove the Americans out, but the Germans had lost six hours to the 117th.

All across the Mortain battlefield, it was the same story: harsh German attacks, heavy artillery and tank fire, and a determined American defense that slowed the advance, all under heavy fog, mostly from the River Sée.

But at 11 am, a new element entered the battle as the fog finally burned off, revealing the entire Normandy front under clear skies. The porcine but capable Lt. Gen. Heinrich von Luttwittz, commanding 2nd Panzer Division, ordered his support columns to take any available cover. On Hill 314, Weiss and Bartz grinned broadly at each other, seeing those “columns of enemy armor and foot troops streaming [toward us] from the east and northeast.” The pair began calling down artillery fire on the Germans.

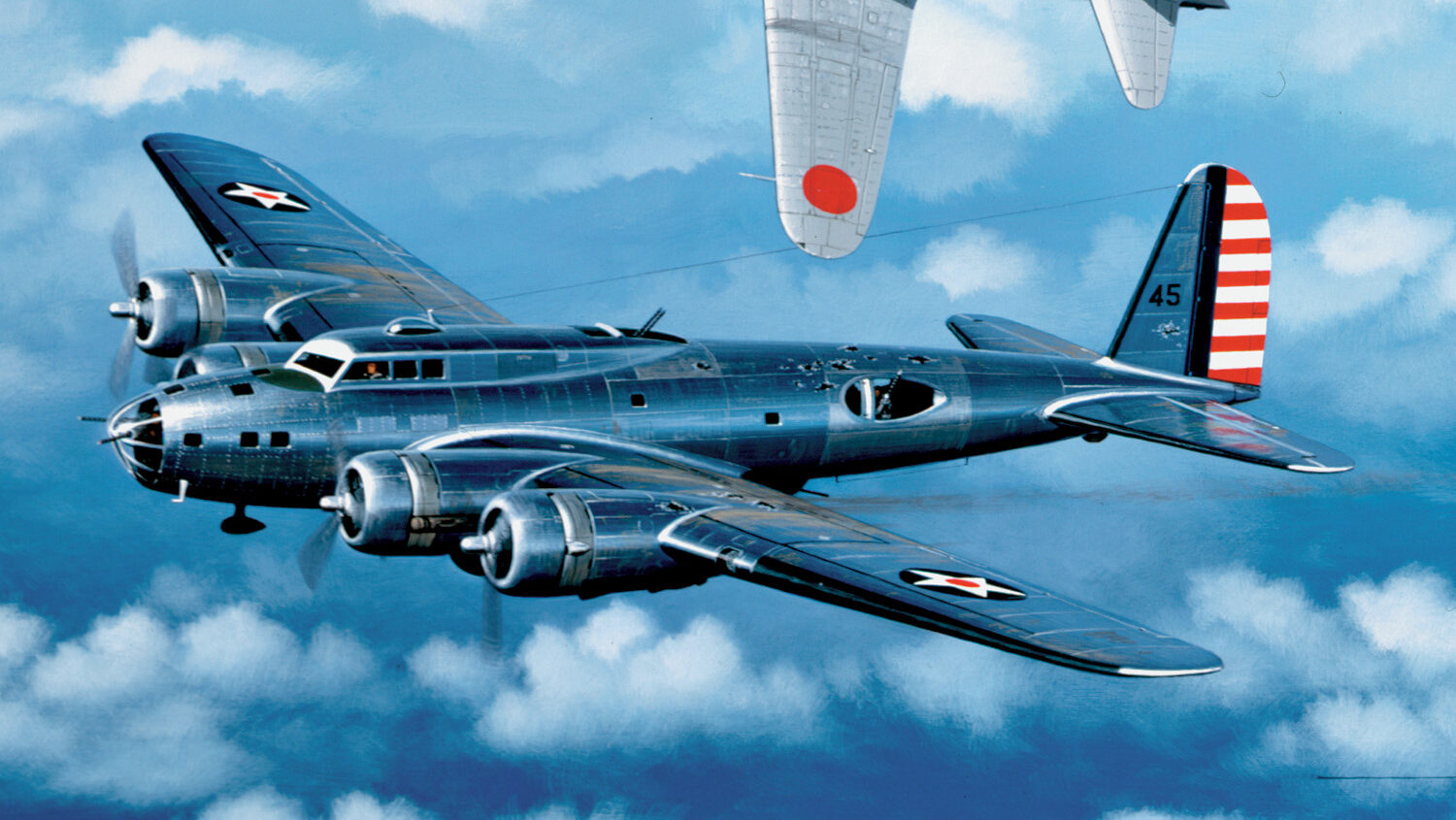

Soon they would get more. Bradley saw the seriousness and weight of the German counterattack and put in a request to Lt. Gen. Elwood “Pete” Quesada, the dashing commander of the U.S. Ninth Air Force, which owned the Republic P-47 Thunderbolt attack planes and P-51 fighters that had been carving up German movement for weeks. Quesada saw the opportunity immediately. In a superb example of Allied cooperation, he reached out to Air Vice Marshal Sir Harry Broadhurst, who commanded 10 squadrons of deadly Hawker Typhoon fighter bombers that could dive at 500 miles per hour and cut loose 60-pound rockets that turned even Tiger tanks into shreds of metal.

The two Allies worked out a plan: the RAF would shoot up vehicles in the Mortain area while American planes would fly missions behind German lines to attack Luftwaffe bases and intercept any German aircraft that dared to venture toward the battlefield.

Wing Commander Charles Green briefed the pilots, dressed in their shirt-sleeves, dark glasses, and silk scarves, while mechanics checked the Typhoons and warmed up the engines. “This is the moment we have all been waiting for, gentlemen,” he said. “The chance of getting at Panzer tanks out in the open. And, there are lots of the bastards.” Green pointed at the Mortain-Saint Barthélémy road on his big map and told his pilots to concentrate on the lead tanks and jam the highway. Flying time to the target was 15 minutes. The Typhoons would take off in pairs, attack individually, then head home and get rearmed and refueled for another strike. There would be a continuous cycle of Typhoons over the battlefield. Pilots were warned to watch for mid-air collisions.

From their cockpits, 245 Squadron pilots looked down on wrecked towns and villages, blasted-open vehicles, and battle smoke from Hill 314. They had no trouble spotting the German columns. They were stretched out along a straight road. The 245 pilots swooped in parallel to the column in line astern at 4,000 feet, winged over, and swept down. German panzer gunners opened up with light flak and tracer, their only defense. Then 245 Squadron raked the tanks with 20mm cannon fire and launched their rockets, following their training procedure of “diving point … release point … scram!” they ripped open tanks and thinner skinned vehicles with explosions, forcing them to a fiery halt and their crews to disperse into ditches, unable to advance.

Within an hour, 245 Squadron was back on the ground for refueling and rearming, then took off again. The pilots had quite a tale to tell. Their rocket attacks were pulverizing the German columns. New Zealander Desmond Scott reported, “As I sped to the head of this mile-long column, hundreds of German troops began spilling out into the road to sprint for the open fields and hedgerows. There was no escape. Typhoons were already attacking in deadly swoops at the other end of the column and within seconds the whole stretch of the road was bursting and blazing under streams of rocket and cannon fire. Ammunition wagons exploded like multicolored volcanoes. A large, long-barreled tank standing in a field just off the road was hit by rockets and overturned into a ditch. It was an awesome sight, plane smoke, burning rockets, and showers of colored tracer.”

The attacks created massive destruction, shocking the German troops under the bombardment. Warner Josupeit, a 1st SS Panzer Division machine gunner, said later, “The fighter bombers circled our tanks several times. Then one broke out of his circle, sought a target and fired. As the first pulled back into the circle of about 20 planes, a second pulled out and fired. So they continued until they had all fired. Then they left the terrible scene.

“A new swarm appeared in their place and fired all their rockets. Black clouds of smoke from burning oil climbed into the sky everywhere we looked. They marked the dead Panzers. Finally the Typhoons couldn’t find any more Panzers so they bore down on us and clawed us mercilessly. Their rockets fell with a terrible howl and burst into big pieces of shrapnel.”

The fear and destruction infected the higher German command level. The Seventh Army’s chief of staff reported, “The attack has bogged down since 1 pm because of heavy fighter-bomber operations and the failure of our air force. [Our high command] never attached enough importance to the air situation; that made the movements and the supply for the operations doubtful.”

The only ground pounders that saw any cheer in the situation were the Americans of the 30th Division, particularly those on Hill 314, who had box seats for the Typhoon attacks, some of them practically on top of their positions. Sergeant Wendell Westall of Illinois watched a Typhoon flash by and said to a pal, “Sure as hell, that one damned nearly parted my hair!”

The RAF’s hammering did not stop. German tank machine gunners ran out of ammunition. The U.S. Army Air Forces joined in the destruction as well, once they had finished massacring the Luftwaffe’s fighters.

As more Typhoons swooped down to attack, the Germans intensified their attacks, particularly on Hill 314. But if the ground defenses were thin and weak, their defending air and artillery cover—called in by Weiss and Bartz—slammed down on the Germans, keeping them off the hill. Worse, Hobbs and Bradley recognized the serious situation in Mortain and were sending reinforcements to relieve what was now being called “The Lost Battalion.”

As dusk settled over the battlefield, the last Typhoons headed west, leaving a scene of horror behind them: blazing tanks torn into grotesque shapes, their 88mm guns bent and twisted … dead men lying in bizarre angles … all under clouds of black smoke from the raging fires.

Of the 70 German tanks that made the attack, 40 were destroyed, and some of those damaged were repaired, a tribute to the skill of German tank recovery teams.

So far, the 116th Panzer Division had not done well under American pressure. XLVII Panzer Corps commander Lt. Gen. von Funck, an SS man, blamed 116th’s commander, Lt. Gen. von Schwerin, a Wehrmacht officer, for the “Greyhound” Division’s sluggishness, and the two yelled at each other. A furious von Funck demanded that Kluge and Hausser relieve von Schwerin of his command, which was done at 4 pm.

As dawn rose over La Roche-Guyon, Kluge’s headquarters, the German field marshal studied situation maps and read reports that showed the immensity of the disaster facing him. Four of his crack panzer divisions committed to the Mortain offensive had suffered immense casualties and gained virtually no ground, stopped cold by Hill 314 and RAF Typhoons. To the north, the First Canadian Army had launched a massive night attack on Falaise with 600 tanks. To the south, Lt. Gen. George Patton’s Third U.S. Army was still driving east toward Argentan, which meant Kluge’s assault force at Mortain would be surrounded. But if Kluge cancelled the order, it could cost him his own life. The attack went on, buoyed by German tenacity and Hausser’s high hopes.

It was a grim situation for the field marshal, but just as much for the determined defenders of Hill 314, who were enduring friendly and enemy bombing and shelling, as a few Luftwaffe bombers slipped through the American fighters, particularly night-attack planes. German tanks that had not been shot up showed their usual tenacity. At 5:07 pm on August 7, two German tanks came within 250 yards of Erichson’s command post on the hill. Private Joe Shipley, a telephone switchboard operator who had never fired a bazooka in his life, grabbed one and knocked out one tank, which frightened off the other. An officer marveled, “He didn’t even leave his seat.”

On August 8, the Germans tried to storm Pulver’s position of A/120th on Hill 285. His radio batteries were dead and his men low on food and water. He took a runner and headed for 1st Battalion’s command post, going through a mortar barrage that shattered his teeth and wounded the runner behind the ear. Even so, both men reached the command post. The battalion commander was amazed—he thought Pulver’s unit had been entirely wiped out. Pulver briefed his boss, retrieved the supplies, and headed back to his hill despite his shattered teeth.

At Hill 314, the Germans tried to attack, despite continued RAF bombing, while the Americans drove east to relieve the defenders. By now, two American infantry divisions and two armored divisions had joined the 30th in the battle. The defenders were running out of supplies, men, and patience. Lacking morphine, clean bandages, and doctors, all the medics could do was put the wounded in slit trenches. Weiss peered through binoculars, wondered when reinforcements would arrive, and saw “a platoon of those gray-green uniforms, assembled to the front for attack.”

The Lost Battalion’s survival depended on Weiss’s radio batteries—Bartz’s were dead—and Bartz looked to Weiss as “having the pale stamp of death on his face. I could not look him in the eyes or study his face for long.”

The Germans attacked, and Weiss called for artillery. “A pall of exploding shells and smoke covered the German infantry, blackening the area around them. Dust and debris shot skyward,” Weiss said. The attack was broken up, but the Germans brought in more tanks and infantry. Once again, American artillery stopped the attack.

After an hour and a half, the Germans tried a new tactic, bringing up their dreaded 88mm guns, which opened fire on the hill’s crags and promontories. Weiss saw German shells bursting “into hundreds or thousands of jagged, body-severing chunks and slivers … [conveying] a brute power, unstoppable strength and deep malice. Big iron cut through the air, shattered boulders into sharp splinters, then bounced erratically over our heads. We crouched down behind the crags, on the face of the cliff to the rear, uncomfortably sheltered.”

Weiss kept calling down counterfire and sent a message from Erichson to Birks at the 120th: “Need radio batteries, medical supplies, food, and ammunition. Men holding their positions. Forward observers Lieutenants Bartz and Weiss doing splendid work. Enemy has been prevented from organizing armor and infantry to attack of overwhelming strength.” Weiss added, “Are we getting reinforcements?”

The Germans continued to attack Hill 314 on the night of August 8/9, to little avail, but exhausting the defenders. Weiss nearly lost track of how many fire missions he called in. “As each separate enemy onslaught crumbled, another took its place,” he said. “They regrouped and returned, again and again.” Weiss wondered why the Germans did not break through.

That was probably because of the determined defense as well as American artillery fire. Sergeant Luther Myers, manning his .30-caliber machine gun, saw German troops charging at him, hurling grenades. One rolled under Myers’ machine gun and went off, jamming it. Tracer rounds flew all over the place, hitting members of his squad. Myers repaired his gun and fired several bursts at the enemy, who fled. “I could have got them all,” he said later, “but it wasn’t worth it, not with my own men crawling across my field of fire.”

Weiss’s radio was still working as dawn broke on August 9. Weiss set himself up in an observation post with a better view and a telephone line to his radioman, so that he could tell the radioman what was going on, and the radio expert could send a short message to 30th Division’s artillery. Weiss called down fire on tanks, bicycle troops, infantry, half-tracks, and motorcycles.

But neither he nor anybody on the hill could cope with hunger. “Five of us shared some bits of chocolate and one K ration,” Weiss said, “normally a single meal for one person.”

The 30th Division artillery commander, Brig. Gen. James Lewis, dispatched two Piper Cub planes loaded with radio batteries and medical supplies, ordering the pilots to drop 71 containers on the hill. One plane was shot down, and the other nearly was. Most of the supplies did not reach the hill. The Army Air Forces tried again with their more reliable C-47 transports, but most of the cargo landed in the German area. American artillerymen loaded their guns with large-caliber shells full of medical supplies and radio batteries and fired them at Hill 314, but the shells broke apart on impact, wrecking the cargo.

The only solution was to relieve the hill. Elements of the 2nd and 3rd Armored Divisions were given the task, with 3rd Armored’s Task Force 3, under Lt. Col. Samuel Hogan, attacking behind the force’s sole tank dozer, under Sergeant Emmett Tripp. “It seemed as if we initially surprised the Germans,” Tripp said later. “We came across some infantry in the hedgerows and sunken roads, eliminating them fairly quickly. Then we came up against at least one Tiger tank, accompanied by Panthers and several Mark IVs.” The men of the 2nd SS Panzer Division attacked the American column from behind and knocked out four tanks, stalling that attack.

Hogan summoned reinforcements, who came under fire. Shaken, they hid under an American M4 Sherman tank. The SS hurled a panzergrenadier battalion at Hogan’s force, and the Americans hit them with phosphorous mortar shells. After night fell, the Luftwaffe’s night attack planes showed up and bombed their own troops. Hogan found the sight “very enjoyable.”

If the Germans could not attack much further due to the RAF bombing, they clearly knew how to hold ground once taken. But they were still determined to seize Hill 314. Atop the height, Weiss saw a convoy of trucks headed toward them, which unloaded more infantry. They formed into a skirmish line.

Weiss called for a fire mission with every battery he could get. In moments, six batteries of 105mm and another of 155mm artillery blasted the attackers. “The powerful impact of all these guns firing together scattered the enemy infantry and bruised them badly,” Weiss said. The Germans hit back with their own artillery, which shook the ground beneath the defenders.

As the day wore on, Weiss and the other defenders saw German vehicles head east loaded with wounded. Then at 6 pm, two German soldiers, brandishing a white flag, walked up to the Americans and spoke to Lieutenant Elmer Rohmiller.

One of the Germans turned out to be an SS officer who was offering honorable terms of surrender. The Nazi admired the ferocity of the American stand, but their situation was hopeless. If the Americans listened to reason, the wounded men would be well cared for. If not, at 8 pm the Americans would be “blown to bits.”

Rohmiller wanted to tell the Germans to go to hell but also figured he should run the request up his chain of command. He blindfolded the pair and led them to Lieutenant Erichson and Lieutenant Ralph Kerley, who commanded E Company. When the SS officers reached the pair, the parliamentaire saluted and said, “I have come to request your surrender … and to offer you and your men safe escort off this hill. You realize, of course, that your position here is hopeless.”

Some of the wounded GIs lying near the command post heard this and yelled, “Don’t surrender!”

“As you hear,” Erichson said, “my men are prepared to argue that one.”

The German had the arrogance of the SS and said, “They are fools; you are not. As their commander, it is your duty…”

“I’m aware of my duty,” Erichson cut in. “Do you have anything more to say?”

“Only this. If you do not surrender by 8 pm today, your battalion will be annihilated.”

Erichson rejected the surrender demand. The Germans left. The Americans atop the hill awaited the German bombardment as the sun sank behind them. Weiss arranged for a ring of artillery fire against night attack. Eight pm came and went, but the Germans did not attack. Finally, in the middle of the night, the Americans heard the distinctive rumble of a German tank headed for one of their roadblocks, and the tank stopped 50 yards away from the crest of the ridge.

The German tank fired a few rounds over the Americans’ heads, then the turret popped open and a helmeted German yelled out, “Surrender or die!”

Weiss stared over the ridge. American rifles were poised. Incredibly, one GI dropped his rifle, ran up the slope, and climbed onto the tank. No shots were fired. Nobody else surrendered. The tank trundled away with its lone captive.

Sunrise on August 10 found the Americans still holding Hill 314 and relief forces steadily driving toward them. The 35th “Black Hawk” Infantry Division, a National Guard outfit from Illinois and Missouri, pushed its way to within a mile of Hill 314 by the close of August 10. To the west, Americans had nearly recaptured St. Barthélémy, and other GIs were inching back into Mortain.

Most importantly, Patton’s Third Army and the Canadian II Corps were creating a giant encirclement around the German offensive. If it continued, the Germans would be caught in a giant bag. Bradley himself recognized the situation, saying to his guest, U.S. Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau, “This is an opportunity that comes to a commander not more than once in a century. We’re about to destroy an entire hostile army.”

Even Hitler and Kluge began to recognize the situation. If Kluge could not prevent the jaws from closing, it would be an irreparable defeat. So far the Germans had lost about 60 percent of their armor in Normandy and could not replace it. A gloomy Hitler reluctantly acceded to Kluge’s request to withdraw from Mortain.

None of these high-level decisions impacted the defense of Hill 314. The Americans were still holding, relying on courage, rumors of relief, and the sight of German troops retreating. Even so, the Germans continued to subject the defenders to artillery and mortar fire. “We could see no end. Our radios had grown very weak. When they gave out, our principal means of defense would be lost,” Weiss said.

But while the Germans kept shelling Hill 314, the Americans were driving on them from every direction. Three miles to the north, Lieutenant Donald Harrison, an ROTC Ohio State alumnus, told his Corporal Robert Baldridge to call down a fire mission on vehicles moving through an intersection just north of Hill 314. The second bracket of shells exploded the German vehicles and sent troops scattering, starting a slaughter that continued all day.

At his observation post, Weiss heard yet another rumble of tanks driving up the Bel Air Road toward the main American roadblock. Down at the roadblock Private Thomas Street was terrified, but his pal next to him started yelling, ‘They’re coming to get us! They’re coming to get us!” Street held his friend tightly to calm him down, but to Street it sounded like the Germans were heading east in retreat.

Street was right. As the sun rose on August 12, Weiss was awakened by his chief assistant, Sergeant John Corn. A haggard, filthy, bearded Weiss found the energy to climb out of his foxhole, walk 40 yards to the ridge, and start looking for targets. At that moment, a German shell exploded in Weiss’s foxhole, killing two men and severely wounding Corn. By 9:45 Corn was dead. “Inside me hate, rage and grief ran together in a stream of violence. I wanted a power that I did not have. I wanted to smash a giant fist for tanks, trucks, troops that I saw now running away.”

Down below, Weiss’s wishes were being answered. The 35th Infantry was finally climbing up Hill 314 against typical German delaying action resistance: snipers, booby-traps, the occasional machine gun, German artillerymen firing off the last of their shells before retreating. Shortly before noon, Lieutenant Homer Kurtz led a party of scouts from G Company, 320th Infantry to the top and met with Lieutenant Ronal Woody. “A guy came up and asked for our company commander,” Woody said later. “Hell, I had my insignia pinned inside my lapel and I looked like a ragamuffin.” Woody told Kurtz that he was the company commander.

Kurtz straightened up and said, “We’re relieving you, sir.”

Woody smiled and said, “Alll-rrrright!”

Down below, Street and his pals saw troops moving in and prepared to fire until they realized the troops were American. Street shook hands with his rescuers and finally looked around at the devastated hill. They also saw an even more impressive sight: ambulances, trucks full of K rations, and press photographers. Street’s outfit, F Company, had suffered nearly 100 percent casualties—only eight men had escaped death, wounds, or captivity.

Weiss was not relieved until early afternoon. He and his two surviving men were too weary to be overjoyed. They packed up their radios and equipment and climbed into their jeep, which had miraculously survived the entire battle. “I flopped into my seat, exhausted, all strength and emotion wrung out. We drove somberly back to B Battery, each of us wrapped in his own thoughts. We had lost something, left it behind on the hill,” he said later.

He was right. Of the 700 men who had fought on Hill 314, only 357 were able to walk off. The rest were dead, wounded, and captured. The 30th Division as a whole had suffered 1,800 casualties. But the Germans had suffered thousands more, along with losing larger numbers of irreplaceable vehicles. American wreck recovery teams hauled off more than 100 abandoned German tanks. The great offensive designed to cut off the American advance was now instead a mousetrap, and all the Germans could do was struggle to extricate their trapped men. Looking down at 40 wrecked German vehicles, Birks said, “It was the best sight I had seen in the war.”

There were a lot of great achievements in the battle. The Lost Battalion received a Presidential Unit Citation for its stand, all chances of German victory in Normandy were lost, and Anglo-American cooperation was at its absolute best.

There were loose ends, of course. At Rastenberg in East Prussia, Warlimont briefed Hitler on the failure of Operation Lüttich. Hitler listened quietly for an hour then said, “Kluge did it deliberately. He did it to prove that it was impossible to carry out my orders.” Kluge would commit suicide four days later.

Another loose end was on Hill 314. Associated Press reporter William Smith White was saying that when the SS officer asked Kerley to surrender, the American had snarled, “I will surrender when every one of our bullets has been fired and every one our bayonets is sticking in a German belly,” and duly reported that.

An astonished Birks congratulated Kerley on the stand and asked him if he had really said that.

Kerley cleared his throat and said, “No, sir. I was not quite so dramatic. What I really said was short, to the point, and very unprintable.”

“That’s telling him,” Birks responded.

Author David Lippman is a frequent contributor to WWII History. He has written on a number of topics and has maintained a website detailing the daily events of the war.