By Robert L. Durham

A battalion of the North Korean People’s Army (NKPA) crossed the Naktong River under cover of night on August 5, 1950. Once across the river, the communist troops moved into position to attack the U.S. Army infantry regiments defending the west side of the Pusan Perimeter. The ensuing battle would be referred to as the Korean War’s First Battle of the Naktong Bulge.

North Korean machine-gun fire tore into Company C of the 3rd Battalion, 34th Infantry Regiment, catching it completely by surprise. Deployed on higher ground, the North Korean infantry held a distinct advantage over the U.N. Command (UNC) troops below them. Most of the soldiers of Company C sought cover in a grist mill. As their casualties mounted, they piled their dead against the outside wall to protect the living.

The United Nations scrambled to remedy the situation. It established the UNC to organize and direct the defense of South Korea. In early July, South Korea placed its military forces under the control of the UNC and its commander, General Douglas MacArthur.

The survivors of Company C were eventually rescued by Company A. The Americans holding out for reinforcements knew that they were out of danger when they heard the rumbling of an M-24 Chafee light tank at the front of a relief column. Company A found a large number of wounded and dead soldiers inside the mill. Only a lucky few from Company C had emerged unscathed. If Company A had not arrived when it did, there might have been no survivors.

The Democratic People’s Republic of Korea and the Republic of Korea fought a series of border skirmishes that gradually escalated in intensity along the 38th Parallel in 1949. With the tacit approval of the Soviet Union, which furnished tanks and combat aircraft to the North Koreans, the North Korean People’s Army invaded South Korea on June 25, 1950, starting the Korean War. The North Koreans captured Seoul three days into its invasion.

At the start of the Korean War, the North Koreans had 135,000 troops against South Korea’s 95,000 troops. At the time of the invasion, there were only a few U.S. combat units in South Korea. These belonged to the dismounted 1st Cavalry and the 7th, 24th, and 25th Infantry Divisions.

The American forces lacked one-third of their authorized size. Instead of having approximately 18,800 men per division, each had 12,500 men. Similarly, the divisions had just two-thirds of their antiaircraft-artillery allotment and only about 20 light tanks in each division, as opposed to the authorized 142 tanks per division. The U.S. Marines had a small number of M-26 Pershing heavy tanks, but the Army was equipped primarily with M-24 Chafee light tanks. These light tanks were no match for the 150 T-34 medium tanks that the Soviet Union had furnished to North Korea.

At the Battle of Osan, fought on July 5, 1950, the North Koreans swept aside the poorly equipped U.S. Task Force Smith. By mid-July the North Koreans were deep into South Korea. By late July, the U.S. and South Korean forces had established a defensive zone in the southeastern corner of South Korea around the port city of Pusan. The UNC forces received no respite, for the North Koreans immediately began assailing their positions along the Pusan Perimeter. This further weakened the U.S. forces defending South Korea.

The perimeter was 100 miles deep and 50 miles wide. The western line paralleled the Naktong River as it flowed toward the Korea Strait. The steep-banked river is about 1,300 feet wide and has a normal depth of six feet. The Naktong formed a defensive barrier for the U.S. forces deployed behind it. A bend in the river about 30 miles from the coastline was known as the Naktong Bulge.

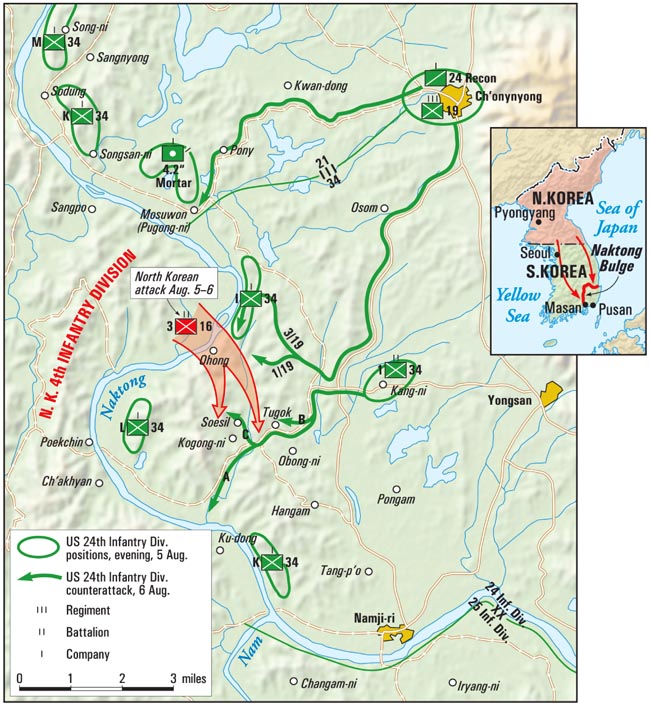

The 3rd Battalion of the 34th Infantry Regiment of Maj. Gen. John H. Church’s 24th Division held the bulge, covering a frontage of 15,000 yards. U.S. Army doctrine called for a full-strength battalion to man a 10,000 yard-long front, but in this case the three battalions defended a five-mile front. Deployed behind the Naktong from north to south were Companies I, L, and K. There was a two-mile gap between I and L Companies, and a three-mile gap separated L and K Companies.

There were at least six ferry crossings along the stretch of the river guarded by the 3rd Battalion. Although the ferryboats were gone, the roads leading to and from the crossings made good fording points. The 4.2-inch mortars supporting the 3rd Battalion were more than a mile to the rear.

Major General Lee Kwon Mu’s NKPA 4th Division faced the Americans across the river. It held the honorary title of the “4th Seoul Division,” having captured the South Korean capital. At midnight on August 5 approximately 800 North Koreans of the 1st and 3rd Battalions, 16th Infantry Regiment, prepared to slip into the Naktong. More would cross the following night.

Most of the men stripped and waded across the shoulder-deep river at the Ohang Ferry site, holding their clothing and equipment over their heads. Others made rafts, which they pushed ahead, to float their clothing and equipment across. No heavy weapons were brought across in this initial crossing.

When they reached the far bank, the North Koreans dressed and advanced toward Yongsan in column of platoons. They moved quietly through the gap between I and L Companies. They had orders not to engage any of the U.S. units defending the river unless the Americans blocked their advance or they were detected.

Nevertheless, the North Koreans assaulted the right flank of Company L, which was deployed at the head of the Naktong Bulge, early that night. Rifleman Leonard Korgie said they heard movement and fired. The firing seemed to set off a rush of North Koreans from the rear and both flanks.

“They wrestled the weapons from us as we fired,” said Korgie. The enemy soldiers clearly were trying to take prisoners from whom they hoped to glean valuable intelligence. Korgie threw his helmet at them and made a run for it. After running up two hills, he collapsed from a combination of dysentery, heat exhaustion, and fatigue. He tumbled headfirst down the hill and rolled for about 40 yards. He and several other Company L soldiers made it to the relative safety of the 34th command post at 2 AM.

The North Koreans eventually overran the Americans’ 4.2-inch mortar position. Most of the troops escaped to the rear. Lt. Col. Gines Perez, commander of the 3rd Battalion, made his way back three miles to the 1st Battalion command post, where he gave Lt. Col. Harold Ayres a report on the North Korean troops’ river crossing. North Korean artillery and mortar fire had severed the Americans’ communications lines.

Approximately 200 North Koreans attacked Battery B of the 13th Field Artillery Battalion at dawn. North Korean machine-gun fire tore into the battery. Shortly afterward, the North Koreans began shelling the battery with their 82mm mortars. This knocked out Battery B’s fire direction center.

A few American artillerymen tried to escape by running through rice paddies, but none of them made it. The battery engaged the North Koreans for two hours, during which it took fire from three sides.

The artillerymen had only one escape route, which was the road behind the guns. They withdrew with one howitzer and seven trucks. Most of the men retreated on foot while under fire. They were forced to crawl through the rice paddies on their stomachs to avoid getting hit by small-arms and machine-gun fire. Most of the men escaped.

Colonel Charles E. Beauchamp, commander of the 34th Regiment, ordered Ayres to launch an attack along the Yangson-Naktong River Road with his 3rd Battalion. Ayres issued orders for the men of Company C to mount trucks and advance along the road. Meanwhile, the men of Companies A and B, as well as the battalion’s weapons company, would follow on foot. The previous day 187 replacements had joined the battalion, but the new troops were untried in battle.

Ayres set out in a jeep ahead of the troops with his operations officer and assistant operations officer. They arrived at the 3rd Battalion command post, which had been vacated, and waited for the trucks to appear. When they arrived, the enemy opened on them, wounding two men. Ayres ordered Captain Clyde Akridge, commander of Company C, to seize the high ground. The tempo of the enemy fire increased dramatically. Enemy rounds hissed past. Akridge was struck three times.

Ayres took shelter with the weapons platoon leader and mortar men. They fired 60mm mortar fire on the North Korean position until they ran out of ammunition. The mortar sergeant stood up to direct the fire, only to be almost cut in two by machine-gun fire. Casualties mounted. Ayres knew that to influence the outcome of the battle, he would have to return to Companies A and B. He and several staff members dashed through a rice paddy. “I had never heard a bullet hit water,” recalled Ayres. “It was a weird sound.”

The North Korean assault threatened two key positions, Cloverleaf Hill and Obong-ni Ridge, in the center of the Naktong Bulge. Most of the Americans reached the slopes of Obong-ni Ridge, and from there they worked their way to a vacant artillery position. Battery B of the U.S. 13th Field Artillery Battalion had been forced to retreat after battling the enemy for two hours. The artillerymen abandoned four howitzers and nine vehicles when they withdrew. It took Ayres several hours to reach the two companies.

The North Koreans continued firing their small arms and automatic weapons. Dead and wounded soon filled the dry creek bed where the Americans had taken shelter. The fight continued for several hours until nearly half the company was killed. Those in the gristmill resolved to hold their ground. Soldiers manning a .50-caliber machine gun on an abandoned personnel carrier kept the enemy at bay. First Lieutenant Charles E. Payne, the company’s senior officer, asked for volunteers to go for help. Private Robert Witzig offered to undertake the dangerous mission.

Witzig dashed 25 yards to a field and then crawled through its furrows. “I probably got about 20 yards and was blown up into the air and landed on my back,” he said. The shell, which peppered his back with shrapnel, knocked him unconscious.

Witzig regained consciousness only to find a North Korean trying to strip him of his grenades. Witzig killed the enemy soldier with his .45-caliber automatic pistol. He lay in the field for a long time until two of his friends found him and dragged him to safety. In the meantime, the troops had successfully made contact with friendly forces and reinforcements were on the way.

The tank spearheading the relief column inadvertently fired on the American soldiers in the gristmill in the mistaken belief that communist troops were inside. However, Company C did not suffer any additional casualties from friendly fire. The arriving American infantry found only a handful of Company C survivors of holding out at the mill.

Since the North Korean attack was still unfolding, Company A scrambled to stabilize the situation, but the enemy by then had captured Cloverleaf Hill and Obong-ni Ridge. Church instructed his 19th Infantry Regiment to retake the lost ground. The Americans succeeded in regaining part of Cloverleaf Hill, but they could not dislodge the North Koreans from Obong-ni Ridge.

The Americans trapped roughly 300 enemy infantry in a village east of Ohang Hill, a mile from the river, and killed almost all of them. This did not stop the North Koreans, who reclaimed Cloverleaf Hill. Extreme heat and lack of food and water had brought American offensive efforts to a standstill. For that matter, the Americans were even having a difficult time holding their ground. Each time they gained ground, the North Koreans drove them back.

To reinforce the beleaguered American frontline troops, senior commanders rounded up engineers, mechanics, and cooks and pressed them into action as riflemen. But replacements were not keeping up with losses. The effectiveness of both the 24th and 34th Infantry Regiments was at roughly 40 percent. The battalions each had fewer than 300 riflemen. The rifle battalions were critically short of ammunition, Browning Automatic Rifles, machine guns, and mortars. In addition, the American infantry regiments lacked trucks needed for transporting troops to the battlefront.

It had been almost impossible for the North Koreans to reinforce their troops engaged on the east side of the Naktong during their attack on the Bulge because of the threat of bombardment during the daylight hours by American artillery and aircraft. North Korean engineers worked feverishly to construct makeshift bridges that could carry their troops across the Naktong during the night.

They completed several bridges made of sandbags, logs, and rocks across the Naktong River on August 7. The bridges were one foot below the normal level of the river, and for that reason were hard for the enemy to destroy.

As the campaign was in progress, the NKPA bridged the Naktong and sent tanks and towed artillery across the river to support their troops. The North Koreans also reinforced the forces already engaged by sending two more infantry battalions across using as many as 70 boats.

Lieutenant General Walton H. Walker, commander of the Eighth Army, reinforced the American forces engaged along the Naktong Bulge by committing the 9th Infantry Regiment to the fight on August 8. The 9th Infantry was a fresh regiment, but its addition did not really help. The North Koreans had infiltrated into the 24th Infantry Division’s rear area. The American infantry regiments could not clear the enemy from their rear.

Early in their attack the North Koreans had succeeded in encircling Companies A, C, and L of the 34th Infantry, stranding isolated infantrymen two miles behind enemy lines. The troops in the pocket were resupplied by American aircraft, although many of the supplies landed outside their perimeter. On the night of August 8, the Americans came under mortar fire as the North Koreans registered their mortars on the American positions. Fearing that this would be followed by a human wave attack that would overrun their position, the Americans requested and received permission that night to fight their way out.

Captain A.F. Alfonso, commander of Company A, prepared his troops to break out of the encirclement. He placed one squad on point 500 yards ahead of the main body. He instructed his troops that the wounded, who were to be carried in litters, would be in the center of the column. He designated one platoon to serve as the rear guard.

Company A set out along the Yongsan Road. They had no sooner departed the position than the North Koreans attacked their abandoned position. When the North Korean troops found it unoccupied, they began firing their automatic weapons down the road.

Alfonso set out with a small reconnaissance squad to find the safest route to friendly lines. He found the battalion command post and organized a rescue convoy of trucks and ambulances to pick up the troops. But while he was gone, his company broke up into smaller groups. One group of 70 men from the rear guard found itself pinned down for several hours by heavy machine-gun fire. Only 40 men escaped; the rest were either picked up by the rescue convoy or wandered into the command post from various directions.

The men carrying the wounded on litters had the most difficulty. The wounded troops screamed and moaned as they were transported—there was no way to carry the wounded men without jostling them. The original plan had been for the stretcher bearers to be relieved periodically by men from the rear guard, but that did not happen given that the marching column disbanded. The survivors eventually located the relative safety of the 9th Infantry’s command post.

The North Koreans widened their hold on the Naktong Bulge, giving them more opportunities to infiltrate the rear areas of the U.S. forces. On August 9 they occupied the village of Namji-ri, just inside the 24th Division’s sector. The 25th Division was to the south. A bridge still stood at this town, which enabled the NKPA’s entrance into the 25th Division’s northern flank. By midday on August 10, the North Koreans had moved toward Yongsan and established a roadblock south of the city. That night the North Koreans were less than three miles from the city. Possession of Yongsan would cut the 24th Division off from supply and reinforcement.

By the following day, the entire NKPA 4th Division had crossed the Naktong River and entered the bulge. Colonel Beauchamp believed Yongsan would fall soon. The 24th Division headquarters assembled about 135 reinforcements from eight different rear-echelon units. These clerks, bakers, military police, and reconnaissance troops were placed under the command of Captain George B. Hafemen. The force had two tanks for support. Hafemen’s orders were to stop the enemy’s eastward advance.

The 2nd Battalion of the 27th Infantry Regiment was assigned the duty of helping to clear the enemy south of Yongsan. A constant stream of Korean refugees clogged the road. The battalion was pushing its way through this traffic flow when a refugee cart overturned and a load of rifles and ammunition spilled out. A dozen North Koreans disguised as refugees bolted across an open field and American riflemen shot eight of them.

At dusk the North Koreans started putting increasing pressure on the defenders of Yongsan. A regimental commander said there were dozens of American and enemy troops all over the area and they were all busy surrounding each other. In one of these encounters, Private Lawrence Y. Bader of the 9th Infantry covered his patrol’s escape. He remained behind and held off the enemy until he was killed, which earned him a posthumous Distinguished Service Cross.

The 2nd Battalion of the 17th Infantry pushed north toward Yongsan on August 12. The battalion ran headlong into entrenched enemy troops, who fought back with machine guns, mortars, and small arms. An air strike helped to drive the enemy from their positions. The strike aircraft killed 100 North Koreans and wounded many more. The Americans captured a dozen machine guns and several 14.5-caliber antitank rifles.

A major menace to the Americans, besides the enemy push on Yongsan, was the blocking of the main supply route between Yongsan and Miryang, which were about 20 miles apart. Before midnight on August 11, vehicles passed over the main supply route with no difficulties except for a few sniper shots. In the predawn hours of August 12, two ambulances of the 1st Ambulance Platoon from Yongsan, loaded with wounded, were hit by automatic weapons fire. The driver of the second ambulance was wounded and the ambulance pitched into a ditch. The first ambulance turned around and the medics rushed the wounded from the second ambulance into the first for the journey back to Yongsan.

A detachment from the 14th Engineer Battalion guarded a three-and-a-half-mile section of the main supply route. The 100 men were divided into four groups stationed at “engineer posts” at 800-yard intervals.

The North Koreans struck engineer posts three and four on the main supply route at dawn with heavy rifles, machine guns, and grenades. The fighting lasted for several hours. The engineers at post three withdrew to post one. The Koreans cut down all of the retreating Americans, except for Sergeant John Kavetsky, who hid in a rice paddy, and took possession of both engineer posts. Meanwhile, the soldiers at engineer post four split up, half heading for engineer post one and the other half unwittingly heading for the abandoned post three. When the retreating American soldiers reached the deserted post three, they were captured by the North Koreans.

On the morning of August 13 the soldiers of Task Force Hill, under Colonel John G. Hill, moved east from Yongsan to clear the main supply route. As they advanced, they cleared North Koreans from foxholes. Some of the foxholes contained as many as six enemy soldiers. Offered a chance to surrender, the North Koreans either fought to the finish or blew themselves up with their own hand grenades. During this operation, the Americans capture four pieces of heavy artillery, two of which were U.S. 105mm howitzers that the North Koreans had captured.

By the end of August 13, Task Force Hill had eradicated NKPA resistance south and east of Yongsan, relieving the city of enemy pressure. Hill then ordered K and L Companies to withdraw from their exposed positions along the Naktong. He instructed their commanders to take up a new position behind the 1st Battalion where they would serve as reserve for the regiment.

Task Force Hill then sought to push the North Koreans back across the Naktong River. First, the troops focused on eliminating enemy positions south and east of Yangson. Next, Colonel Hill assaulted the enemy positions on Cloverleaf Hill and Obong-ni Ridge. The task force was far from full strength for this attack. The two battalions of the 9th Infantry were down to two-thirds of their strength, and the three rifle companies of the 1st Battalion, 34th Infantry had barely enough men to form Company A.

A heavy rainfall, starting in the early hours of August 14, prevented the planned air strike. The artillery delivered a 10-minute preparation, and then the infantry started for the objective. The two battalions of the 9th Regimental Combat Team attacked Cloverleaf Hill, while Company B of the 34th Infantry began an assault on the north end of Obong-ni Ridge.

Cloverleaf Hill was shaped like a four-leaf clover, hence its name. There was a gap between Cloverleaf and Obong-ni Ridge through which the main supply route ran. Obong-ni Ridge, which ran northwest to southeast, consisted of a half dozen connected hills, each of which was known by its height in meters. They ranged in height from 102 to 153 meters.

The soldiers of B Company nearly secured Obong-ni Ridge but were driven back by 8 AM. On the other side of the road, on Cloverleaf Hill, a fierce battle of attack and counterattack occurred. The 1st Battalion suffered 60 casualties in one hour of fighting. The two battalions in the assault managed to secure the lower slopes but not the main mass of the hill. The night of August 14 was marked by continuous combat as the North Koreans repeatedly attacked the American defensive perimeters.

On the morning of August 15, the Americans continued the attack on Cloverleaf Hill and Obong-ni Ridge. A savage grenade fight ensued on the southern slopes of Obong-ni. The 2nd Platoon of Company A traded rifle fire with the enemy at 10 paces. After almost an hour, 24 of the 35 soldiers involved the attack had either been killed or wounded. All along the line, the North Koreans fought the Americans to a standstill.

Hill and Church suspected that by this time the North Koreans were worn down by attrition. North Korean bodies, weapons, and equipment were scattered all around the northern end of Obong-ni Ridge. Unfortunately, the Americans no longer had the manpower to take the enemy positions. General Walker decided to send Church the 5th Marines as reinforcements. The Marines were already on their way to Miryang, where they were to act as Army Reserve, so it was a small matter to have them move farther forward to Obong-ni Ridge.

On August 17 Marine Corps air and artillery prepared the ridge for the attack. They knocked out many enemy mortars and either cut down or scattered many NKPA troop concentrations. The rear of the North Korean position showed much confusion. Company B of the Marines, which was led by Captain John Tobin, advanced to the attack. Tobin positioned his machine guns and the 3rd Platoon on nearby Observation Hill to support the rest of Baker Company’s assault.

Tobin was preparing to reinforce the 1st and 2nd Platoons on the ridge when he received a severe wound from enemy machine-gun fire. After making sure that Tobin received medical care, Captain Francis Fenton joined the heavily engaged platoons on Obong-ni Ridge. He arrived in time to find both platoons pinned down by North Korean gunfire. The enemy fire was coming from several peaks on the ridge, as well as from the town of Tugok on the opposite side of the road.

The Marines on Observation Hill committed the 3rd Platoon to reinforce the attack. The main hindrance to the assault was the flanking fire coming from Tugok. The platoon requested fire support from its weapons company. The mortar men lobbed shells at the enemy position, suppressing the fire coming from Tugok. The 1st Platoon then outflanked the North Korean 18th Regiment. Just before dusk, the riflemen captured Hill 102. The 2nd Platoon fought its way up the ridge to capture Hill 109. At that point, they were relieved by Company A. As they withdrew, the soldiers of the 2nd Platoon took their casualties with them.

Company A’s 1st and 2nd Platoons moved off the southern end of Observation Hill and crossed the rice paddy in front of Obong-ni Ridge. Meanwhile, Marine aircraft and heavy artillery blasted the forward and rear slopes of the ridge. The two platoons each had a machine-gun section. Company A reached the halfway point, encountering only sniper fire, but soon came under heavy machine-gun fire. First Lieutenant Robert Sebilian pushed his 1st Platoon up the draw between Hills 109 and 117. He stood in the open, pointing out enemy positions to his NCO, until an explosive bullet shattered his leg. Technical Sergeant Orval McMullen took command of the platoon and pushed his riflemen forward. When the 1st Platoon advanced southward toward Hill 117, it found itself pinned down by heavy fire.

On the 1st Platoon’s left flank, North Korean artillery cut the 2nd Platoon in half. The Americans pressed up the draw between hills 117 and 143 but were brought to a halt when the casualties in its skirmish line became too heavy to sustain the assault. Second Lieutenant Thomas H. Johnston, the platoon leader, rushed upward alone, only to be gunned down by enemy fire. Command devolved to Technical Sergeant Frank Lawson, who attempted to resume the attack. North Korean guns and grenades thwarted the renewed advance, bringing it to a halt. By that point in the battle, the 2nd Platoon had suffered so many casualties that it was at squad strength.

Company A then committed the 3rd Platoon to the attack. First Lieutenant George Fox, the platoon commander, led his troops into a rice paddy where they were hit by a mortar barrage. Fox tried twice to charge the ridge, but he could not get a foothold. Fox and one of his riflemen attempted to reach Johnston, but they could not retrieve his body because of enemy machine-gun fire. Yet they did confirm his death.

While the attacks on the ridge were underway, the four M-26 Pershing tanks of the 3rd Platoon, Company A moved forward of the road cut, supporting the attack with 90mm shells and machine-gun fire. They concentrated their fire on the crest of Hill 102, destroying a dozen antitank guns and several automatic weapons. The North Koreans put up a tenacious defense. One of the tanks received three direct hits from enemy mortars, and all four tanks were hit by a total of 25 antitank projectiles. One man was slightly wounded, but the tanks did not sustain significant damage. When Company B secured Hill 102, the tanks returned to their command post to refuel and replenish their ammunition supply.

The Americans soon learned that four North Korean T-34 tanks were approaching their lines on the main supply route. Marine tank crews scrambled to engage the North Korean tanks. Second Lieutenant Granville Sweet, the tank commander, ordered his first section to load 90mm armor-piercing shells. The Americans called for air support, and F4U Corsairs of Marine Aviation Training Support Group 33 responded. The strike aircraft made a run against the enemy tanks, destroying the last tank in the column of four. The first three tanks continued down the road. When the first tank reached the bend in the road, it became visible to the troops on Observation Hill. American 75-mm recoilless rifles and M20 Super Bazookas that fired 3.5-inch antitank rockets were positioned on the hill.

The first enemy tank received fire on the right track from a 3.5-inch rocket, but it continued moving forward. Two 75mm rounds disabled the left track and blasted the front armor. The enemy tank burst into flame but kept shooting, its 85mm rifle and machine gun blasting away aimlessly. The enemy tank wobbled around the curve and came face to face with the leading Marine M-26 tank. The American tank fired two quick rounds from its 90mm gun, both of which hit the NKPA tank, which exploded. One member of the crew climbed out of the burning tank, but the Americans cut him down.

The second T-34 came around the bend and was struck in its right track by a 3.5-inch rocket. The injured tank tottered around the curve and took another shot in the gas tank from a 3.5-inch rocket. The tank wobbled off the road, firing its 85mm rounds wildly into the air.

The second M-26 pulled up beside the first, and the two tanks fired six 90mm rounds into the T-34 without effect—it kept up its firing into the sky. A North Korean tank crewman opened the turret hatch and tried to escape, but a bazooka team fired a 2.36-inch white phosphorus incendiary round that ricocheted off the turret and into the tank. The interior of the T-34 cooked off.

The Marine Corps tanks fired seven more shells into the enemy tank, one of them ripping through the turret and exploding the hull. Marine tanks, recoilless rifles, and rockets tore into the tank. The NKPA tank exploded into a fireball.

The Americans used Corsairs, Pershing tanks, recoilless rifles and rockets to destroy the North Korean T-34s. Although considered invincible before this battle, the T-34 proved vulnerable to these weapons systems.

Throughout the day, evacuation of the dead and wounded had been a major concern. Litter bearers carried their loads across the rice paddies under enemy fire. The Marines had to use every ambulance they had, as well as additional Army ambulances, to transport the wounded to the 5th Marines’ aid station. With night coming on, the soldiers on Obong-ni Ridge established defensive perimeters.

Across the main supply route, the 9th Regimental Combat Team cleared Tugok and Finger Ridge with little enemy resistance. By darkness, the 19th and 34th Army Regiments had seized their objectives. Although their ranks were thin, the Army and Marine units were in good positions for the next days’ assault. The American troops had the 4th NKPA Division nearly encircled.

But the North Koreans were not yet whipped. Just before 10 pm the NKPA hit the center of Company A with a barrage of mortar shells, followed by white phosphorus. In the gully where Company A’s 60mm mortar battery was stationed, almost every man was seriously wounded, leaving Company A’s Captain John Stevens without a mortar section. The edge of the barrage caught 3rd Platoon’s area, leaving several men wounded. The most serious casualties were evacuated, but the slightly wounded stayed where they were. Although injured three times, platoon commander Fox stayed to fight with his men. After the initial attack, everything settled down to an eerie quiet as the men sheltered in their foxholes, waiting for the North Koreans’ next move.

At 2:30 am on August 18, the Marines of Company A heard enemy movement on Hill 117. Suddenly, machine guns on the peak delivered a hail of bullets. Hand grenades were rolled down the hill into the Marine perimeter. A North Korean platoon attacked them, ending up in the middle of the exhausted and depleted 2nd Platoon. For 30 minutes the 2nd Platoon battled with North Korean troops three times their number. One reason for their holding out for so long can be contributed to Lawson, who refused to be evacuated even though wounded multiple times. The fatigued survivors of the 2nd Platoon were overrun in the predawn hours, and the brigade line was pierced. For some reason, the North Koreans did not exploit the penetration.

At the same time as the North Korean troops attacked Company A’s 2nd Platoon, two platoons assaulted Company B’s defensive perimeter on Hill 109. Despite illuminated shells fired by 81mm mortars, the enemy attacked painstakingly by throwing squadrons of grenadiers and submachine gunners against B Company. Automatic weapons fire from Hill 117 covered the NKPA soldiers. North Koreans slipped past Marine foxholes and overran the rocket gunners, mortar men, and clerks of Captain Fenton’s command post, succeeding in eradicating the defenders.

Stevens had lost effective control of Company A during the night, although the situation was not as desperate as it appeared. While Stevens stabilized the center, his commanding officer, First Lieutenant Fred F. Eubanks, made lone forays up the gully.

After the North Korean breakthrough, Second Lieutenant Francis Muetzel, Company A’s machine-gun officer, was wounded and left for dead. When Muetzel regained consciousness, he fought his way back to the Marine lines and assisted Eubanks. Company A eventually pulled back and called in artillery fire on the position it had abandoned.

By first light on August 18, the NKPA attackers had spent their strength. This left Company B in undisputed possession of Hills 102 and 109. North Korean machine gunners on Hill 117 covered the retreat of their surviving fellow soldiers.

The U.S. Marines called in an airstrike on Hill 117, and a lone fighter plane dropped a 500-pound bomb. The Marines swarmed up Hill 117 and secured it. The North Korean soldiers panicked and fled down from the crest. Stevens’ machine gunners and riflemen mowed down the retreating North Koreans.

Company A swept south and captured Hill 143 with little resistance. The 3rd Platoon assaulted Hill 147, where most NKPA retreated while a few fought to the bitter end. The Marines marched in column of fours down the western slope. When they opened fire on the North Koreans, the enemy formation broke and the troops fled in panic. The Marine infantrymen moved southward down Obong-ni Ridge, capturing the rest of the peaks with no resistance.

While the 1st Marine Battalion secured Obong-ni Ridge, the 3rd Battalion started an assault from the northern end of Obong-ni Ridge to Hill 206, the next peak to the west. The 9th Infantry Regiment supported this attack from its position on Cloverleaf Hill. The 3rd Marine Battalion secured the hill within an hour with essentially no opposition.

U.S. forward air controllers, forward artillery observers, and frontline infantry units all reported seeing the enemy retreating west toward the Naktong River. The forward artillery observers adjusted air bursts and quick-fuse artillery fire on these forces. Some of the artillery fire directed at the river crossing sites consisted of delayed fuses for greater effectiveness against infantry swimming across the river. Fighter aircraft caught large numbers of North Koreans in the open and strafed them.

By the evening of August 18 it was clear that the Americans had soundly defeated the North Korean 4th Division. The division lost 34 artillery pieces, the largest of which was a 122mm howitzer.

The Americans suffered 600 killed and 1,200 wounded, captured, or missing in the First Battle of the Naktong Bulge. North Korean casualties were estimated to be 1,200 killed and 2,300 wounded. Half of the North Korean wounded died from lack of sufficient medical care.

The upshot of the First Battle of the Naktong Bulge was that it resulted in the complete erosion of the combat effectiveness of the NKPA 4th Division. The famous division never recovered from its devastating losses in the hard-fought battle.

The U.S. Army succeeded over the course of the battle in substantially improving its antitank capabilities to the point that the North Koreans no longer had a decisive advantage as a result of their T-34 tanks. As the fighting continued at the Pusan Perimeter into September, the U.N. Command forces gradually gained superiority as the Americans buttressed their frontline units with additional armor and heavy weapons capable of defeating the North Korean Army.