By Simon Rees

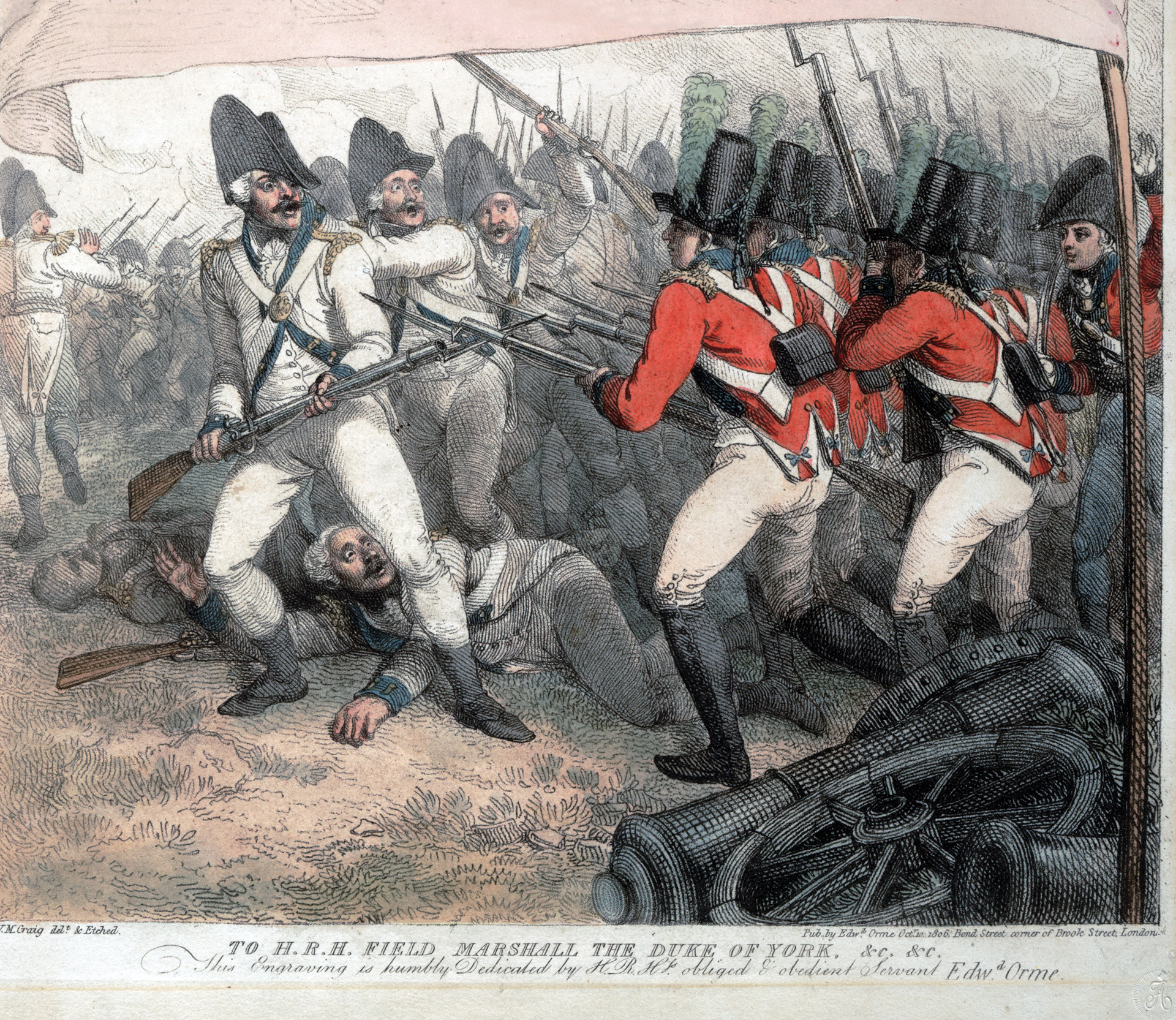

The soldiers of the French 1st Light Infantry surged forward toward the double line of the British Light Battalion. As the French advanced across the level plain in Calabria, British cannon balls crashed into their ranks. The misery experienced by the French soldiers was turned into a nightmare at 250 yards when the gunners switched to case shot, which consisted of shells filled with hundreds of musket balls that mowed down men by the dozens.

The British light infantry fired its first volley at 150 yards. Owing to their exemplary musketry skills, at least half of their shots hit an enemy soldier. When the veterans of the 1st Light came to within 80 yards a second volley crashed out. Almost every musket ball struck home. General of Brigade Louis Compere, commander of the 1st Light Infantry, was among the wounded, but he continued to wave his men forward. The British fired their third volley at 20 yards. The carnage was horrific. Whether the French 1st Light could survive the storm of iron and lead in the opening minutes of the Battle of Maida on July 4, 1806, would be known in a matter of minutes.

The sanguinary clash just 60 miles north of the Strait of Messina occurred during the War of the Third Coalition that pitted France and its allies against a coalition that eventually comprised the major powers—Great Britain, Austria, and Russia—and also the lesser powers—the Kingdom of the Naples, Kingdom of Sicily, and Sweden. Although the war technically began in 1803, it did not get into full swing until the following year when France’s aggression in Italy prompted Austria and Russia to join Britain in its continuing conflict with France.

During lengthy negotiations, Russia asked Britain to send an expeditionary force into the Mediterranean to support a possible joint expedition against 14,000 French troops stationed in the Kingdom of Naples’ eastern ports. The Russians wanted the option of creating a southern front to draw French resources away from central Europe, while simultaneously removing a potential threat to their hold on the Ionian Islands, particularly Corfu. The British were less certain. The Kingdom of Naples was part of a dual monarchy that included the Kingdom of Sicily, and at the time it was neutral. Intervention might create an unnecessary sideshow where the chances of success were far from guaranteed.

Great Britain suspected the Russian urge to intervene would recede once campaigning in central Europe started in earnest. But London was worried about Napoleon seizing Sicily, the island that dominates the Mediterranean’s seaways, and using it as a base to strangle Britain’s considerable military and economic interests in the Near East. An expeditionary force stationed on Malta that was capable of sailing for Sicily and defending it would be an excellent form of insurance against this threat. Its presence would also perform a face-saving role as Russia and Austria were expected to perform the bulk of the fighting on land and wanted a show of good faith beyond Britain’s generous war subsidies. Having weighed the pros and cons, Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger’s administration decided to equip and send an army of several thousand to Malta during the spring of 1805.

The Two Sicilies was covertly receptive to the idea of intervention because it wanted to eject the French garrisons. In addition, the autocratic royal family had personal scores to settle: it was a cadet branch of the Bourbons and the wife of King Ferdinand, Maria Carolina of Austria, was Marie Antoinette’s sister; however, they needed to tread carefully as the French had already backed the Parthenopean Republic, a short-lived puppet regime that seized the Kingdom of Naples in late 1798 and sent Ferdinand and Maria scurrying to Sicily. Napoleon had been content to leave the royal family in place after a successful Neapolitan counterrevolution, although he demanded they pledge strict neutrality and host French forces in return. These had been withdrawn during the short Peace of Amiens of 1802 but reintroduced once war with Britain resumed.

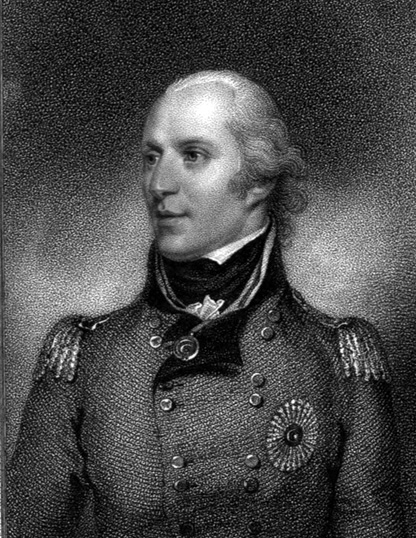

Few of these complexities would have bothered the minds of most soldiers in the British expeditionary force. They had sailed into Valetta harbor on July 22 after suffering a miserable voyage packed with delays caused by Admiral Pierre-Charles’s famous pre-Trafalgar run across the Atlantic and back, and almost every man on board just wanted to get off the fetid transports. Their commander was Lt. Gen. Sir James Craig, a veteran of the American Revolutionary War and something of a specialist in light infantry tactics; however, he was in poor health by 1805 and his reserves of strength would wax and wane depending on the pressures to come. His primary mission was to reorganize the Malta garrison, assist the Russians, and keep a sharp eye on Sicily.

Craig had already made an important mistake by deciding his 300 dragoons would sail without their horses in a bid to minimize shipping difficulties and costs. Their mounts would only be purchased when needed, although the British soon discovered that good animals were rare in the region and only available for large sums. Indeed, it was something of a minor miracle that Britain’s ambassador to the Neapolitan Court, Hugh Elliot, had procured 200 horses before Craig’s men eventually arrived in the Kingdom of Naples. Only a few seedy-looking creatures were obtained afterward and all of the available animals had to be dedicated to the baggage train, pulling guns, or given to the officers, leaving the expeditionary force bereft of cavalry support.

Some important correspondence was waiting for Craig at Malta, including a notification that he would be officially subordinate to Russia’s Mediterranean commander, General Maurice Lacy, in the event of a joint operation. Another letter was from Lacy himself, informing Craig that he and members of his entourage were traveling incognito through the Kingdom of Naples, testing the political waters, monitoring the French, and examining the terrain. In addition, he wanted to know the expeditionary force’s strength and state of available transports as the British would have to ship Russian forces from the Ionian Islands if necessary. As Craig’s staff started tallying vessels, he reported to Lacy a force of 5,000 infantry, 400 engineers, 400 gunners, and the 300 horseless cavalrymen.

His next job was to assess and integrate some of the men already on Malta into a revamped expeditionary force. Realizing he lacked experienced formations, Craig created a special Light Battalion by combining his light companies and topping them up with “flankers,” men from the regular companies noted for their marksmanship. A composite grenadier battalion was formed using similar methods, while there were several foreign units to evaluate as well. This included 740 Corsican Rangers who hailed from the island of Napoleon’s birth and were sworn enemies of the emperor, and the Regiment de Watteville of 725 Swiss mercenaries led by Colonel Louis de Watteville. Improved liaison with the Russians was also established, although they presented a poorly devised contingency plan for landings in the Kingdom of Naples that needed thorough revision.

In the meantime, French demands that Ferdinand recognize Napoleon’s title as King of Italy had just reached Naples. Technically, this could amount to a form of homage, and an outraged royal family informed the Russian ambassador Tatishcheff they wanted an alliance with the tsar and to join the Coalition at once. He excitedly drew up a secret treaty that Ferdinand signed on September 10. The details were revealed to Craig as a fait accompli, followed by a request from Lacy that the contingency plan be put into effect. But the Russians were about to learn that diplomacy and duplicity often went hand-in-glove at the Neapolitan court. Napoleon had suddenly announced the French garrisons would be increased to 20,000 men, panicking the dual monarchy until it secretly learned the emperor wanted to remove all of his men and use them to reinforce Marshal Andre Massena’s army in northeastern Italy.

All the Two Sicilies needed to do was reaffirm its strict neutrality and the garrisons would be gone. The dual monarchy agreed and a formal ratification took place on October 8; a bewildered Tatishcheff was told this new deal had been signed under duress and that Coalition landings should proceed. Although the royal family loathed Napoleon, they considered the outcome an excellent one: French forces were evacuating as promised, just as two allied armies were about to land and assume responsibility for protecting the country’s borders. Never mind that Ferdinand’s signature had just released an enemy army for operations elsewhere, or that its departure negated the main reason for intervention, namely the destruction of the enemy garrisons and the diversion of Napoleon’s resources away from other theaters.

British transports reached the Bay of Naples on November 20 loaded with 13,000 Russian troops and 1,500 Albanian irregulars, and the expeditionary force of 7,650. Lacy and Craig now met for the first time, with the Russian general creating something of a stir among the British staff. He was born in 1740 and came from long line of Irish mercenary officers, starting his military career during in the Seven Years War of 1756-1763. This made him seem like a relic by 1805. “He shewed no trace of ever having been a man of talent or information,” wrote Sir Henry Bunbury, Craig’s quartermaster. It was an unduly harsh assessment, although Lacy did himself no favors by wearing a nightcap during councils of war and dozing off when others spoke. With no enemy in the vicinity, and with details of the Austrian defeat at Ulm in mid-October still filtering through, the two generals decided they could do little more than defend the Kingdom of Naples’ border and hope for Coalition success elsewhere.

The British established themselves on the Mediterranean flank, near the Neapolitan-held fortress of Gaeta, while the Russians were responsible for the difficult central ground, with more of Ferdinand’s men policing the Adriatic side. Not much was expected of the Neapolitan army as it was poorly led, badly equipped and shoddily supplied. Yet there was no time to correct these glaring weaknesses as details of Napoleon’s staggering victory at Austerlitz on December 2 started to arrive, followed by news that Russian forces were retreating out of central Europe and Austria had surrendered via the Treaty of Pressburg on December 26. The Two Sicilies was now firmly in Napoleon’s sights, confirmed by a blistering proclamation dated December 27. “Shall we trust again a Court without loyalty, without honor, without sense? No, no!” the emperor said. “The dynasty of Naples has ceased to reign.”

Massena was ordered to take a 30,000-man army south to seize the Two Sicilies and place the emperor’s brother, Joseph Bonaparte, on the dual monarchy’s throne. They were underway by New Year’s 1806 and the British and Russians held a series of crisis meetings in response, with Craig arguing that it was impossible to hold a thin line across the Italian peninsula against an experienced enemy that could be easily reinforced. The British should immediately sail for Sicily and the Russians return to the Ionian Isles. Lacy was inclined to agree but noted he was obligated to defend the Two Sicilies and that only official word from Russia could release him. Craig pledged to remain at Lacy’s disposal and both men agreed to at least withdraw from Naples, provoking outrage at the Neapolitan court. Maria Carolina even condemned Craig as a coward, but the veteran of Bunker Hill and countless other engagements refused to let accusations of this sort cloud his judgment. Yet others were less sure as a retreat without firing a shot was worrisome in an age when matters of honor often took precedence over strategic interests.

The impasse was broken when an order from the tsar arrived on January 7, instructing Lacy to leave for the Ionian Isles at once. Craig’s health collapsed several days later, although he summoned his remaining strength to assist the Russian departure and oversee the expeditionary force’s own evacuation at the same time. His men sailed on January 19 and reached the Sicilian port of Messina on January 22, only to be refused permission to land and help prepare the island’s defenses.

Neapolitan envoys were already seeking forgiveness from Napoleon and the dual monarchy believed a British army in Sicily would scupper their chances of success. The emperor responded with terms that amounted to an unconditional surrender, a demand that was rebuffed as further entreaties were made. The situation had become a farce because the British remained cooped up in their transports, begging to defend an ally that kept pleading with an implacable foe.

King Ferdinand had sailed for Palermo not long after the British departure, while Queen Maria Carolina and her entourage remained in Naples until word arrived on February 9 that Joseph Bonaparte had reiterated his brother’s terms. Massena’s army crossed the frontier at the same time and the queen promptly fled for Sicily, with the Kingdom of Naples’ fortresses falling behind her without a shot. Gaeta was the only exception and it would stand fast until July 18. The British finally received permission to land at Messina on February 15, the same day Joseph Bonaparte made a triumphant entrance into Naples, and it was not long afterward that Craig, still gravely ill, started handing over command to Maj. Gen. Sir John Stuart. Many thought Craig would die on the voyage back to Britain, but he survived and would go on to serve in Canada.

Craig had ordered the 1st Battalion, 81st Foot to leave Malta for Sicily before his departure, while further reinforcements arrived in the form of the 2nd Battalion, 78th Foot (Highlanders). Stuart rather ungratefully bemoaned this unit’s lack of experience as most of its soldiers were raw recruits. The expeditionary force’s new commander was a somewhat unusual British military specimen. Stuart was the son of a loyalist born in Georgia in 1759; his career included the American Revolutionary War and several important campaigns across the 1790s. He had also won recognition in Egypt, particularly at the Battle of Alexandria, but resented the praise Sir John Moore had received for his part in the same action. Egocentricity and self-promotion were some of Stuart’s worst flaws, but he proved competent enough in the field and possessed a fair eye for both tactical and strategic details.

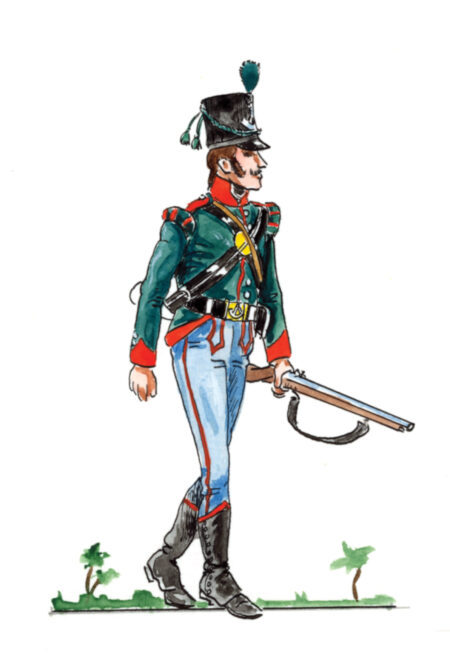

Stuart’s defense of Sicily depended on Royal Navy ships keeping the Strait of Messina clear, affording vital shoreline support. Across that narrow gap of water, Massena’s III Corps under General Jean Louis Reynier had arrived, simultaneously preparing for an invasion of the island and trying to subdue southern Calabria. The unit comprised almost 12,000 men and more than 1,000 cavalry, and it had crushed the last major Neapolitan army at the Battle of Campo Tenese on March 10. However, the French seizure of local produce was prompting guerrilla bands to form, their attacks provoking fierce reprisals and creating a cycle of violence that Reynier found difficult to restrain. Still in his mid-30s, he had been considered a military wunderkind during the 1790s and later Egyptian campaign, although his star had fallen after he killed an officer in a duel not long after returning to France. Almost cashiered, Reynier only regained a position of command when war resumed in 1803, and Massena’s decision to appoint him head of III Corps was considered a new vote of confidence. Getting bogged down in an ugly insurrection was decidedly not part of his plan.

The British compounded Reynier’s difficulties by landing weapons to assist the guerrillas and hiring local fast boats to attack French supply ships. They mistakenly believed he had stationed around 5,000 men in southern Calabria, with the bulk of III Corps to the north. It was actually vice versa, which the British would soon discover because Stuart wanted to land an army near the top of the toe of the Italian boot, aiming to cut off and destroy his opponent’s southern units in quick succession. He wanted to ruin whatever invasion preparations for Sicily had been made so far and then return to the island before Reynier and Massena could properly respond. An army of roughly 5,500 frontline troops, as well as engineers and ancillary staff, was earmarked, the numbers including 550 soldiers from the 20th Foot who would be responsible for sailing on fast ships between Reggio and Cape Spartivento to keep the French guessing Stuart’s intentions. They were commanded by Lt. Col. Robert Ross who would play an important role in events to come and, several years later, would command the army that burned Washington, D.C., in 1814.

With three ships of the line offering protection, Stuart’s men set sail on June 26 and reached the Bay of St. Euphemia on the night of June 30. The landings took place at a northerly point where the village of Gizzeria Lido is now situated and were witnessed by a handful of Polish soldiers under French command. These men promptly rushed inland to raise the alarm as contingents from the Light Battalion, 78th Foot, and Corsican Rangers formed a vanguard under the command of Colonel John Oswald. The British swiftly captured the nearby Bastione di Malta, a mid-16th-century watchtower that still stands, and then marched toward the village of St. Euphemia, located a couple of miles east. It was defended by around 400 soldiers, mostly Polish troops, who had failed to secure their flanks and allowed the vanguard to work its way around the village. Threatened with being cut off, they were forced to make a hasty retreat, leaving several dead behind and almost 80 men taken prisoner. By comparison, Oswald reported just one person wounded, making the action an excellent start for the expeditionary force.

More British troops were soon landing and many were set to work helping the engineers build southward-facing defensives that incorporated the watchtower. The expeditionary force would need a strong position on which to retreat if events went badly, while Stuart thought a redoubt would rally local Calabrian insurgents to the beachhead. In the event, only 200 poorly equipped peasants arrived as most locals decided to avoid the danger of battle in what was clearly a temporary affair. The unloading of troops and matériel continued on July 2, a process slowed by heavy surf, while a company of grenadiers was ordered to take the village of Nicastro, a position that afforded reasonable views of the immediate countryside. The landings were finally complete on July 3. Any satisfaction of a job well done, though, was upset by the unexpected arrival of French units roughly 10 miles to the southeast.

Reynier had ordered a series of forced marches on hearing about the landings and unnerved his enemy by assembling an opposing army at such speed. His men soon occupied excellent defensive ground stretching west from the foothills of San Pietro a Maida toward an area near the modern village of Acconia. Scrambling to gather intelligence, Stuart and his staff concluded they faced an army of 4,000 infantry, 300 cavalry, and four light artillery pieces by the evening of July 3, and guessed that between 2,000 and 3,000 reinforcements would arrive in two or three days’ time. This helps explain Stuart’s eagerness to attack on July 4: he believed the expeditionary force outnumbered the newly arrived French by several hundred, potentially tipping the scales in his favor when combined with the larger number of British guns. By contrast, delaying an attack would guarantee the arrival of Reynier’s reinforcements and leave the expeditionary force in an extremely precarious position.

Stuart was quick to hammer out a basic plan. His men would march south along the Bay of St. Euphemia’s shore, reassemble at the River Amato’s mouth, and then turn inland to press the French left, which was on weaker ground. He was also gambling Reynier would receive no reinforcements of note that night, an unsuccessful bet as General of Brigade Louis Fursy Henri Compere’s 2,400-man brigade marched into the French camp on the evening of July 3. This formation comprised the veteran 42nd Regiment and the elite 1st Light, one of the best infantry units under French arms. After the battle, the British contended they had faced 7,000 infantry plus the 300 cavalry and four guns. But Reynier and other French sources recorded between 5,100 and 5,500 men present. That still meant Stuart was outnumbered on July 4 as he would take 4,800 men into the field, leaving four companies of Watteville’s regiment, four 6-pounders, and a couple of howitzers to protect the landing site.

The British attack force comprised four brigades. The rather grandly titled Advanced Corps was commanded by Lt. Col. James Kempt and was, for all intents and purposes, the 730-man Light Battalion supported by some detachments from the Royal Corsican Rangers and the Royal Sicilian Volunteers. Brig. Gen. Lowry Cole led the 1st Brigade, which featured the 2nd Battalion, 27th Foot and the composite Grenadier Battalion, while Brig. Gen. Wroth Acland headed the 2nd Brigade, comprising the 2nd Battalion, 78th Foot and 1st Battalion, 81st Foot. The 1st Battalion, 58th Foot and the remaining five companies of Watteville’s men made up Oswald’s 3rd Brigade of reserves. Kempt, Acland, and Cole would each have three or four pieces of light artillery in support, while the companies of the 20th Foot commanded by Ross were expected shortly, albeit most likely after July 4.

Interestingly, the French also overestimated their enemy’s scale, calculating Stuart had 6,000 troops and, rather fancifully, around 2,000 Calabrian insurgents. Reynier was undaunted by what appeared to be a larger opponent and vowed to “throw the English into the sea.” He was already on record for disparaging British military leadership, and the expeditionary force’s earlier misfortunes under Craig only appeared to confirm his bias. A quick and decisive victory would destroy most of the army protecting Sicily, making a French invasion of the island much easier. Others urged him to wait until enough reinforcements had arrived to make victory certain, but Reynier rejected this advice. It was simply too good an opportunity to miss and an attack on the landing site was ordered for the next morning.

But the British would steal a march on Reynier and used the cover of night to move their artillery to the Amato’s mouth in advance of their main force. It was back-breaking work as the gun crews discovered the roads were little better than dusty tracks through terrain covered with heavy undergrowth. The rest of Stuart’s men started heading south as dawn broke on July 4, with Oswald’s reserves trudging along the beach as Cole, Acland, and Kempt’s brigades squelched through the marshy pastures beyond. The Amato was reached at 7 am, with the British then turning east but staying north of the river. Kempt took the right, Acland the center, Cole the left, and Oswald just behind the center, with the strength of Reynier’s positions more fully revealed as they neared. Alexandre de Roverea, then a captain with the Royal Sicilian Volunteers, later shuddered at the potential danger ahead: “[Their ground] could be defended foot by foot and would have cost us many lives,” he said.

Reynier was surprised but pleased to see the British advance. From his perspective, Stuart had made a critical mistake by moving away from the beachhead’s defenses and naval support. The previous evening’s attack orders were promptly cancelled and a general advance called for instead. Instead, Reynier’s men would cross the Amato, swing west, and then plough through the enemy, rounding up any survivors in their wake. Rather ironically, the British thought Reynier was the one who had blundered by quitting his excellent ground. “Imagine our surprise and joy when we saw the French troops leave [their] advantageous position and descend into the plain!” Roverea said. He was also impressed by the subsequent vista of both sides advancing to engage. “The coup d’œil was magnificent—our fine troops as steady and in good order as on the parade ground, vis-a-vis the French, also in line, their arms glittering in the sun,” he said.

The two armies inadvertently advanced in echelon on a southeast to northwest axis as the undergrowth interrupted the pace away from the Amato River, which meant Compere’s brigade and the Advanced Corps would clash first nearest the river. At first glance it seemed Reynier’s plan for a swift victory might come to early fruition as Kempt’s men were facing a more experienced and much larger foe. The first shots rang out 300 yards east of where the modern highway crosses the river, with around 200 voltigeurs (skirmishers) using the cover of reeds on the Amato’s southern bank to needle their enemy. Roverea was given temporary command of a Corsican Ranger company and ordered to cross the shallow river and neutralize this threat; however, they were outnumbered and pushed back into the path of the Light Battalion’s right flank, forcing Kempt to send extra troops over to bring this preliminary phase to a quick end. The British suffered a number of casualties during the action, including their only officer to be killed that day, Captain Murdoch Maclean of the 20th Foot’s Light Company.

The Advanced Corps came to a halt at roughly 9 am as Compere’s brigade continued to close the gap. Kempt’s supporting artillery had unlimbered, with their first shots slamming into the 42nd Regiment’s 1st Grenadier Company and killing six men. There was no counterbattery fire as the four French pieces were targeting Acland’s men at maximum distance and causing minimal damage. Compere’s brigade now had to endure a 15-minute advance to reach the enemy. The 1st Light was somewhat to the south and ahead of the 42nd Regiment. As it advanced against the British double line, the 1st Light suffered heavy losses from the well-served British artillery and devasting musketry.

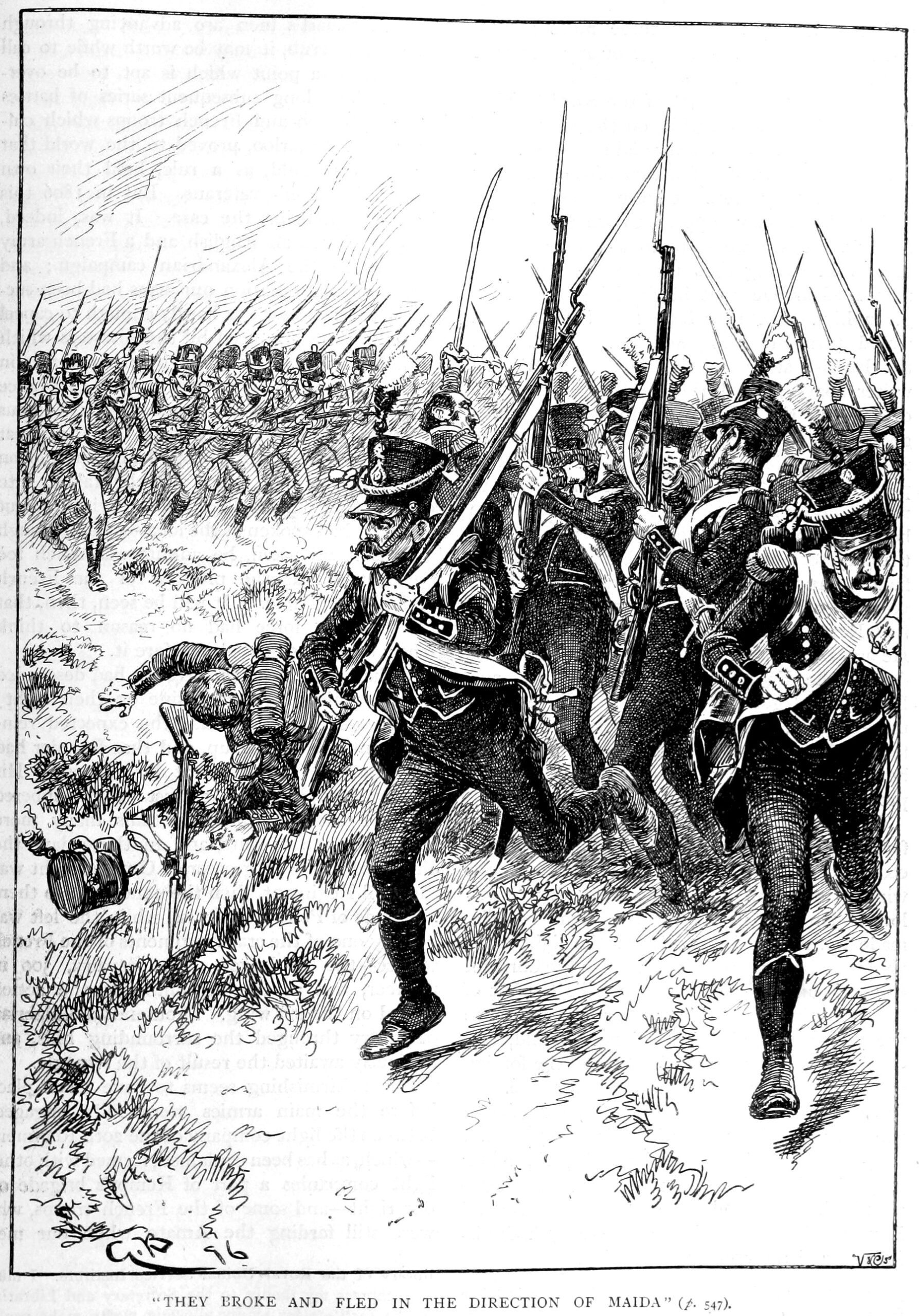

Sensing their enemy was on the verge of disintegrating, the veterans of the British Light Battalion surged forward, stabbing and slicing with their bayonets. Compere did his best to rally the 1st Light. Already badly wounded, Compere had his horse shot out from under him. He survived the deadly melee when a British officer hauled him to safety. The 42nd Regiment responded to the collapse by wheeling back and taking up a defensive position to protect Reynier’s southern flank, with the remnants of the 1st Light streaming past as the British chased them from the field.

The Advanced Corps’ position was covered by Oswald’s 58th Foot as the British center finally moved up. Their view had been obscured by the growing heat haze and dust created by French cavalry feints being made to unnerve and distract. This worked to some extent as Bunbury noted a temporary and rather botched effort by some units to make a square during the advance. Opposing Acland’s men were those of General of Brigade Luigi Peyri’s foreign brigade, which comprised the 1st Swiss Regiment and the 1st Regiment of Polish infantry, units from which had already performed poorly at St. Euphemia on July 1. Their heart was not in this particular fight and the Poles fell back as the 81st approached. Meanwhile, Peyri’s Swiss continued to advance. They wore red jackets and, because of the dust and smoke, the 78th thought they were some of Oswald’s reserves trying to backtrack after pushing too far ahead.

Their inexcusable error was only realized when the battalion received an enemy volley. Along with some of the 58th and the brigade’s supporting artillery, the 78th started to return fire and watched with satisfaction as the Swiss gave ground. Acland now called his men to a halt and tried to realign them after the gap with Cole’s men on his left had widened, creating a breach the enemy might try to exploit. Indeed, Reynier had already noted this opportunity and ordered the 23rd Light of General Antoine Digonet’s brigade to press away from the northwest and focus on the gap instead. But this proved impossible as the unit’s three battalions were fast closing with Cole’s men and disengaging so close to the enemy would have invited disaster. All Reynier could do was support Digonet’s advance with whatever reserves were left, including the cavalry and four pieces of artillery.

French sharpshooters on the far left of the British line were already sniping from cover and Cole had to send four companies of the 27th to deal with this unwelcome attention. Their efforts were successful at keeping the voltigeurs at bay until a large patch of dry grass was ignited by French artillery fire, the billows of smoke causing confusion and unsteadying nerves. British difficulties were amplified when enemy cavalry started to threaten the left as well, forcing Cole to remove two grenadier companies from his right to act as reinforcements.

The bulk of Digonet’s men were closing in at around 11 am and it seemed the French might achieve their breakthrough after all. Bunbury was watching this drama unfold when he received word that Ross’s companies had just landed and were marching at top speed to the sound of gunfire. He dashed over to meet them and explained Cole’s urgent need for help.

Not missing a beat, Ross had his men race through the burning stubble and form up at an angle to the French cavalry and other formations pressing Cole’s left. They fired a relatively effective volley and then joined Cole’s men in forcing the dismayed 23rd Light to withdraw. Reynier had no options left and decided to exit the battlefield, taking his battered army northeast. He had been seen exhorting his men at various points during the fighting, while Stuart was a static presence by comparison, remaining with his staff and making casual observations as the odd musket ball whizzed past. Bunbury thought little of his commander’s performance that day and noted Stuart had fallen into a kind of daze after the 1st Light’s rout. “He dawdled about, breaking into passionate exclamations: ‘Begad, I never saw anything so glorious as this!’ It’s the finest thing I ever witnessed.’” From that moment on he was an altered man and full of visions of coming greatness.

Bunbury also claimed Stuart’s apparent lethargy forced him to ride between brigade leaders to share vital information. This was both unfair and rather self-serving; in truth, the battlefield was small enough for an eye to be kept on most of the action and Stuart would have used aides-de-camp or other officers to assess the situation and report back. More pertinent, perhaps, was the criticism that he missed an opportunity to destroy Reynier’s army as it retreated. However, an all-out assault could have been costly as most enemy units remained unbroken and were being screened by cavalry. They were also withdrawing into hilly terrain where solid rear guards could be mounted. In addition, Stuart would have wanted to minimize further casualties as the job of reducing Reynier’s remaining southern outposts lay ahead, along with the need to resume Sicily’s defense. The battle and scorching heat had left his men parched and too exhausted for much further action.

Hundreds of Reynier’s men were left dead or dying on the plain, and Stuart noted the burial of 700 enemy troops in his post-battle dispatch dated July 6. The British had also captured 1,000 men, the majority of whom were wounded, while Reynier later reported 300 injured with him after the battle, most likely the walking cases. In total, the French suffered a staggering 2,000 men killed, wounded, or captured during the fighting, with Compere’s brigade having suffered most. By contrast, the British recorded one officer, three sergeants, and 41 other ranks dead and 282 wounded for a total of 327 casualties, which was considered extraordinarily low. As the surgeons and grave diggers got to work, the expeditionary force returned to an area near the landing site and each brigade was rewarded, in turn, with a refreshing plunge in the Mediterranean.

Cole’s brigade was taking a dip when one of Bunbury’s officers spotted a cloud of dust and galloped over, shouting that French cavalry was fast approaching. The men rushed out of the sea, grabbed their muskets and belts, and formed a stark-naked battle line. Fortunately it turned out to be a false alarm. A herd of Italian water buffalo had been spooked nearby and it was their cantering about that had caused the officer to panic. Further frivolity occurred when Stuart and his staff were entertained by Rear Admiral Sir Sidney Smith on board his flagship HMS Pompeethat evening. Smith enthusiastically held up a shawl during the proceedings and showed his guests how to make a “turban after the fashion of the most refined Turkish ladies,” said Bunbury.

Stuart’s subsequent mopping-up of southern Calabria was rapid, with all of Reynier’s remaining garrisons surrendered by July 24. The French invasion preparations for Sicily had been thoroughly wrecked, while the British also netted plentiful supplies and almost 1,400 additional prisoners. Meanwhile, Reynier’s surviving army and several units not present on the battlefield slogged their way into the Catanzaro region, waiting for reinforcements that failed to materialize because insurgents kept cutting French lines of communication. Reynier was forced to retire farther north, with many of his men harried out of Crotone by cannon fire from HMS Amphionand it was only on August 4 that around 4,000 half-starved scarecrows reached the comparative safety of Cassano all’Ionio. Order had broken down twice along the way, with the small towns of Strongoli and Corigliano Calabro sacked, looted, and virtually destroyed.

The expeditionary force was back in Sicily by the time London and Paris had fully digested the battle’s details. The French people were left largely bemused and, except for those with friends or family involved, not just a little disinterested. True, an army comprising some of the emperor’s finest had been bested, but Maida’s smaller scale made it seem like a niggling defeat on the edge of an all-conquering empire. And so what if Reynier had bungled? There was plenty more talent to choose from. It was a different story across the English Channel, with news sparking a bout of national jubilation. Stuart’s dispatch on July 6 helped set the tone: “Never has the pride of our presumptuous enemy been more severely humbled, nor the superiority of the British troops more gloriously proved,” he wrote. There was good reason for the hyperbole because comprehensive victories on land had become a rare commodity for the British people. Maida was a boost when the United Kingdom needed it most, and it proved that Napoleon’s soldiers, who were starting to appear invincible across 1805 and into 1806, could be comprehensively defeated.

Stuart decided to return home not long after reaching Sicily. General Henry Fox had arrived on July 22 to head the Mediterranean theater, while Sir John Moore was slated for second-in-command and Stuart was not the kind of man to play third fiddle. Back home, he received the thanks of Parliament, a £1,000 annuity, and the title Count of Maida. Stuart returned to Sicily in 1808 after he was appointed Mediterranean commander and defeated a French invasion attempt during 1810. The praise was more muted this time as the Iberian Peninsula had become the focus of Britain’s military efforts and now captured the general public’s attention.

But at least Stuart had already won his place in the sun. Craig’s efforts were largely ignored, despite getting the expeditionary force out of the potentially lethal Neapolitan quagmire. The Battle of Maida would never have happened without his insistence that British forces should evacuate and secure Sicily at the start of 1806. Regardless of the criticism, though, the greatest laurels were owed to the man behind the musket as Maida was undoubtedly a soldier’s battle. There were no elaborate plans of attack or cunning use of stealth, just a hard slog that required steady volleys and great courage in the face of an experienced enemy. Cole’s correspondence dated July 11 rightly credits his troops with the victory: “Everything is due to the steadiness and good discipline and gallantry of the troops, without which we must have been defeated.”