By Patrick J. Chaisson

Paratrooper Lt. Col. Bill Yarborough was flying into hell. As he prepared to jump from a Douglas C-47 transport plane then approaching the coast of Sicily, hundreds of American antiaircraft gunners below started shooting at him.

Yarborough could not believe what he was seeing. Did an enemy bomber somehow get into the U.S. troop carrier formation? How, he wondered, could those gun crews down there not recognize our C-47s for what they are?

The volume of fire only increased as Yarborough’s unarmored transport aircraft neared its drop zone. “The flak became worse and worse,” he recalled years later. “We were flying through a solid wall of this stuff.”

Bill Yarborough watched helplessly as a C-47 on his left burst into flames and fell out of the sky. Other planes, including his own, began taking hits as their pilots desperately maneuvered to escape the deadly gunfire. Those troopers who managed to jump were scattered all along the length of Sicily’s southern coast. Yarborough and his stick of 14 men came down near the walled city of Biscari, 12 miles from their intended drop zone.

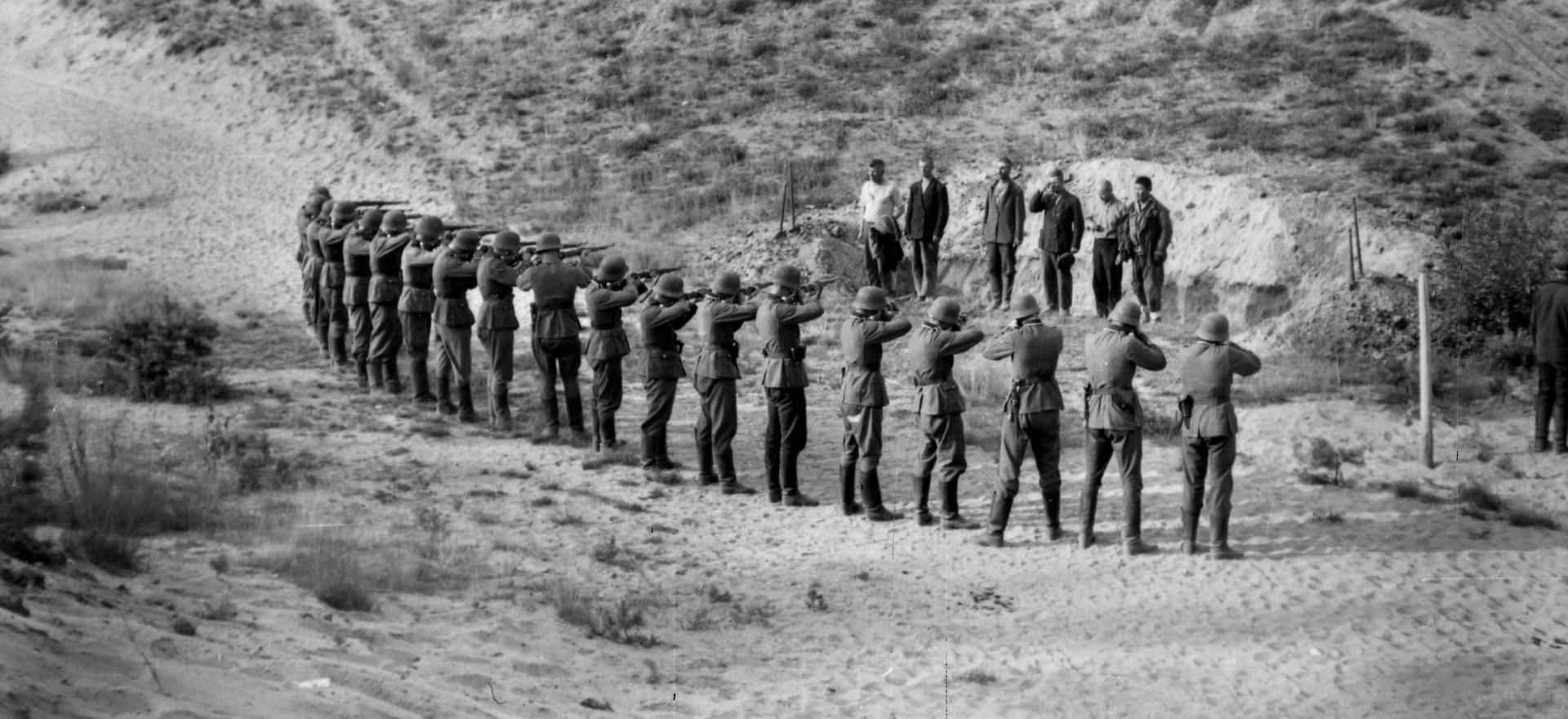

This debacle, which took place on the night of July 10-11, 1943, resulted in the loss of 23 C-47 transports and 229 soldiers killed or wounded. It was one of the worst friendly fire incidents of World War II.

As he made his way toward Allied-held territory, Yarborough seethed with rage. He knew it all could have been prevented—in previous assignments he had learned from bitter experience exactly how to prevent such fratricidal contact. Yet no one in his current unit cared what this highly intelligent combat veteran had to say.

The frustration and bruised pride building inside Lt. Col. Bill Yarborough grew with every step he took on Sicily’s rocky soil. These powerful emotions would soon draw him into another kind of battle, a contest of wills fought against one of the most formidable combat commanders in the U.S. Army, Maj. Gen. Matthew B. Ridgway.

William Pelham Yarborough, son of a career Army officer, was born in Seattle, Washington, on May 12, 1912. He entered the United States Military Academy in 1932, displaying both an interest in military history and a talent for mechanical design. Four years later, Yarborough graduated from West Point as a second lieutenant of Infantry, reporting for duty with the 57th Infantry Regiment at Fort McKinley in the Philippines.

Following promotion to first lieutenant and transfer to Fort Benning, Georgia, in 1940, he followed with great interest Nazi Germany’s lightning advance across Poland, the Low Countries, and France during the war’s first year. Yarborough was especially intrigued by Hitler’s airborne forces; the aura of adventure and danger surrounding these elite “sky-soldiers” stirred him to volunteer when the U.S. Army announced it was forming its own parachute test battalion.

Now wearing captain’s bars, Yarborough for a brief time commanded Company C, 501st Parachute Infantry Battalion. On March 3, 1941, he went to Washington, D.C., on a special mission: to design and procure a qualification badge for the Army’s newest airborne troopers. He swiftly sketched out a silver insignia measuring 1½ inches in length and consisting of an open parachute extending from a pair of stylized wings. Now his new design required authorization by the War Department’s notoriously byzantine bureaucracy.

“I personally took the correspondence relative to the badge’s approval from one office to another until the transaction was complete,” Yarborough recalled. “This operation took me one entire week, eight hours a day.” He then had Philadelphia jeweler Bailey, Banks, and Biddle manufacture 350 sets of jump wings in time to be presented at a battalion ceremony on March 14.

Impressed by Yarborough’s resourcefulness, the commanding officer of Airborne Command’s Provisional Parachute Group, Lt. Col. William C. Lee, brought him on board as a test officer. There this bright young captain developed such iconic items of airborne regalia as the paratrooper boot—a sturdy cap-toe model normally worn with bloused (tucked-in) trousers. He also fashioned a unique combat uniform for parachutists as well as several aerial delivery containers intended for heavy weapons and supplies. Yarborough later received U.S. patents for many of his inventions.

In July 1942, following temporary promotion to major, he accompanied Maj. Gen. Mark W. Clark to London as II U.S. Corps airborne adviser. In that role Yarborough helped plan Operation Torch, the Allied invasion of North Africa. He later accompanied the 2nd Battalion, 509th Parachute Infantry Regiment (2/509 PIR) on a 1,500-mile flight from England to seize vital airfields in French-held Algeria.

This mission, which took place on November 9-11, 1942, went poorly. Yarborough’s C-47 transport was shot up by Vichy French fighter planes over Algeria and had to crash-land onto a dry lake bed. He then led surviving U.S. paratroopers on a punishing walk across the desert, only to discover their objective had already been taken by American tanks. On November 15, Major Yarborough jumped with 2/509 PIR onto Youks les Bains airfield near Tebessa, where a now friendly French garrison welcomed its new allies to the fight against Germany.

While the Americans’ first airborne actions in North Africa resulted in mixed success at best, Bill Yarborough emerged from Operation Torch as an officer on the rise. A skillful planner, he also demonstrated tenacity and physical courage in battle. Freshly promoted Lt. Gen. Mark Clark wanted Yarborough on his Fifth Army operations staff, but the youthful paratrooper had other ideas.

All West Point graduates knew the path to higher rank and responsibility in wartime required assignment to a combat command. Only one parachute battalion existed in the Mediterranean Theater of Operations, and its commander was not going anywhere soon. For career officer Bill Yarborough, his best chance for promotion remained in one of the five airborne divisions then organizing Stateside.

He requested transfer to the 101st Airborne Division, led at the time by his old boss and mentor Bill Lee. Instead, Yarborough received orders assigning him to the 82nd Airborne Division and command of 2nd Battalion, 504th PIR. That unit, stationed at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, was preparing for overseas deployment when he arrived in February 1943.

Yarborough did not want to be there. At Fort Bragg he encountered many officers who had already advanced well past him in rank. For instance, he knew Reuben H. Tucker III as a poor student who barely managed to graduate from West Point in 1935. Now Lt. Col. Tucker (his immediate superior) was due to pin on the insignia of a full colonel as regimental commander, 504th PIR. All the while, battle-tested Bill Yarborough remained a major.

It also galled him that no one in the 82nd seemed interested in his combat experiences. Yarborough was “hoping for some kind of recognition” of those exploits, expecting people to say, “Hey, you’ve been in parachute operations; tell us how it was.” But the “All-American Division” was a big, impersonal organization. Everyone in it was busily preparing for Operation Husky—the invasion of Sicily—set to take place that July.

Bill Yarborough’s promotion to lieutenant colonel, which came in May, did little to soothe his mounting resentment. He eventually learned who was responsible for his plight when division commander Maj. Gen. Matthew B. Ridgway said he personally requisitioned Yarborough to lead the 2/504 PIR.

It was a morale-crushing piece of news. Yarborough knew his status as a pioneer of airborne warfare meant little to the 48-year-old Ridgway, who had been running the 82nd Airborne since August 1942. He also realized there was no escape from this uncompromising, ramrod-straight professional soldier who tolerated no nonsense from his subordinate officers.

Some troopers, however, adored their hard-charging commanding general. Ridgway’s protégé, then colonel James M. Gavin, vividly described his boss’s leadership style: “He was a great combat commander. Lots of courage. He was right up front every minute. Hard as flint and full of intensity, almost grinding his teeth with intensity.”

Matthew Ridgway demanded a similar level of commitment from his officers. Even before the All-Americans entered combat he fired several leaders who he deemed were insufficiently aggressive. “When the responsibility of command is on your shoulders,” he wrote, “you cannot afford to play along with officers who won’t give you all they’ve got.”

Likewise, there was no room in Ridgway’s organization for malcontents. “I learned very early that one of the attributes of military leadership is knowing when to get rid of a sorehead,” the general once observed. And he already had his eye on a potential troublemaker who was unhappily serving at the head of 2/504 PIR.

The 82nd Airborne’s plan for Operation Husky, its first ever parachute assault, reflected the division’s aggressive spirit. On the night of July 9-10, 1943, a total of 222 C-47s of the U.S. 52nd Troop Carrier Wing would deliver Colonel Jim Gavin’s 505th PIR—reinforced by 3/504 PIR, the 456th Parachute Field Artillery Battalion (PFAB), and a company of airborne engineers—behind beaches slated for invasion by American amphibious forces. The remaining two battalions of Colonel Reuben Tucker’s 504th PIR (plus the 376th PFAB and Company C, 307th Airborne Engineer Battalion) were to stand ready at airfields around Kairouan, Tunisia, on call to execute a second drop should one prove necessary.

This overly complicated scheme failed to account for weather, enemy activity, or the navigational skills of inexperienced troop carrier flight crews. When Gavin’s force went in shortly after midnight on July 10, a 35 mile-per-hour wind and German flak deranged the mission so badly that a mere 425 of the 3,405 troopers jumping that night landed on their designated drop zones.

Nevertheless, those few men fought like demons to take and hold a road junction at Piano Lupo that overlooked the main landing beaches. Other members of Gavin’s regiment, individually or in small groups, caused untold mayhem all across Sicily while making their journey toward American lines. At Biazza Ridge on July 11, about 200 paratroopers pitted raw courage against attacking German PzKpfw. VI Tiger tanks. Miraculously, they held out long enough for General Ridgway (who had come ashore the previous morning) to summon forward American armor and artillery.

Even as the last Germans were being swept off Biazza Ridge, Ridgway gave the order for Tucker’s 504th PIR to jump in that night. The winds had subsided, but enemy bombers still plagued the beachhead area. Multiple warnings went out to Army and Navy antiaircraft commands warning them of friendly air activity to occur after dark; later that afternoon Ridgway discovered to his horror that some gun crews still had not received the word.

Around 2230 hours, a heavy German bombing raid struck Allied ships off Sicily just as the C-47s transporting Bill Yarborough and his battalion approached their drop zone. It started a chain reaction among the jumpy Army and Navy gunners. “One .50-caliber machine gun, situated in the sand dunes several hundred yards from the shore, opened fire,” remembered Captain Willard E. Harrison of the 504th PIR. “As soon as this firing began, guns along the coast as far as we could see … opened fire and the naval craft lying off shore … began firing anti-aircraft guns.”

The slaughter lasted a full hour. When it was done, 60 of the 144 U.S. troop carrier aircraft aloft that night had been damaged—the C-47 carrying Colonel Tucker came home with more than 1,000 holes in its skin. At least 85 aircrewmen perished or were declared missing in action.

The 82nd Airborne’s losses included Assistant Division Commander Brig. Gen. Charles L. Keerans, whose remains were never found. Paratroopers who survived the drop found themselves strewn across 65 miles of Sicilian coastline. It would take days for those not killed outright, captured, or injured on landing to assemble for any sort of organized action.

By July 18, the 2/504 PIR had 250 men present for duty, making it the All-American Division’s most combat-ready infantry battalion. At 0400 hours the following morning, Yarborough’s soldiers stepped off for the city of Trapani on Sicily’s west coast. They passed rapidly through small mountain villages such as Ribera and Sciacca; here, the troopers’ chief difficulty lay in their lack of motorized transportation. Supplies, rations, and especially water could not keep up with the fast-moving infantrymen, who suffered under a blazing summer sun while marching 20-25 miles per day along steep, dustcovered roads.

Their advance was mostly unopposed but nevertheless contained many dangers. Outside Sciacca on July 20, the men of 2/504 PIR ran across a roadblock seeded with land mines. Clearing that obstacle took three hours; beyond it lay an abandoned enemy tank park, artillery position, and airstrip. All evidence indicated the previous occupants had recently departed in great haste.

Yarborough’s paratroopers began their day’s march on July 21 at 0300 hours, with Company F in the lead. Scouts and flankers deployed as the battalion approached Tuminello Pass, a natural defensive position in the hills southwest of Santa Margherita. Dawn had just broken when Italian gunners holding the pass tripped their ambush.

A barrage of well-aimed 77mm artillery shells landed among the surprised GIs, killing six men and wounding another eight before Yarborough’s troopers could find cover. For 30 minutes those cannons, along with accurate small-arms fire, kept Company F pinned down. The Americans had trouble responding; a morning fog helped conceal their dug-in foe.

Finally, Lt. Col. Yarborough got the battalion’s 60mm and 81mm mortars on target while U.S. machine-gun teams began providing suppressive fire. A rifle platoon led by Lieutenant Charles Drew then rushed forward, flushing clusters of surprised soldiers out of their holes at bayonet point. Italian officers, their honor now satisfied, began raising the white flag of surrender.

By 0830 hours it was all over. Yarborough’s troopers had just overwhelmed a stoutly defended enemy strongpoint, capturing hundreds of prisoners in the process. Also seized in this sharp action were five 77mm howitzers as well as vast amounts of matériel and ammunition.

Yarborough pushed out an outpost line before allowing his soldiers to break for lunch. The ration truck had just arrived; it seemed like a good time to let his men enjoy the first proper meal many of them had eaten in days.

Just then Maj. Gen. Ridgway rode up in a jeep. Observing the scene, he barked, “What’s going on here?” Unsatisfied with Yarborough’s answer, the general replied: “If you stay in this area here, you are going to be shelled. Why aren’t you on the road?” Ridgway knew that if 2/504 PIR remained in Tuminello Pass it would make itself vulnerable to an enemy counterattack. “That’s no way to do it,” he scolded. “Keep moving, get going.”

Grumbling, the paratroopers got up and resumed their march. Walking alongside them was a boiling mad Bill Yarborough, furious over his general’s reaction to a battle he felt was well fought. It mattered little that Ridgway was right; this encounter only further enflamed Yarborough’s already wounded pride.

Following the All-American Division’s five-day, 150-mile trek to Sicily’s western tip, Lt. Col. Yarborough found himself serving as military governor to several small villages outside Trapani. Bored with his new responsibilities, still horrified by the 504th PIR’s disastrous night jump, and livid over his treatment by General Ridgway, Yarborough began mouthing off. Typically, regimental- and division-level staff officers caught the brunt of his angry, insubordinate comments.

Yarborough’s “high-spirited stupidity” (as he later characterized this behavior) soon enough reached the attention of his division commander. Summoned on August 2 to Ridgway’s headquarters, the troublesome young colonel received a set of orders relieving him from command of 2/504 PIR and transferring him back to Fifth Army. “I wanted to die,” he remembered afterward.

A few days later, Lt. Gen. Clark sat down with the despondent officer. “I never should have assigned you to that outfit in the first place,” Clark said. “You come back here with me and in due course I’ll see that you get another command.” Meanwhile, Yarborough would serve out his penance as Fifth Army’s airborne adviser for the invasion of Italy at Salerno.

In September 1943, Yarborough put together an audacious but near-suicidal plan to drop the 82nd Airborne on Rome and wrest control of that city from its German garrison. Fortunately, this scheme was called off at the last moment. He also helped organize the 504th PIR’s nighttime jump into the Salerno beachhead on September 11, followed by the 505th about 72 hours later. Both of these missions went relatively smoothly, due in no small part to Yarborough’s insistence on adopting proper antiaircraft fire control measures as well as utilizing specially trained pathfinder teams to help mark the drop zones.

The 2/509 PIR, his old friends from North Africa, parachuted onto an enemy-held village called Avellino as part of the Salerno operation. A now chastened Bill Yarborough got his shot at redemption when Lt. Gen. Clark sent him forward to replace that unit’s commander, known to have been taken prisoner at Avellino. He led the redesignated 509th Parachute Infantry Battalion throughout heavy fighting in the Italian mountains, at Anzio, and on one final combat jump into southern France as part of Operation Anvil-Dragoon in August 1944.

Yarborough went home later that summer to attend an abbreviated Command and General Staff Officers’ course, returning to Italy in October as head of the 473rd Infantry Regiment (which was mostly comprised of former antiaircraft gunners). He earned both promotion to colonel and a Silver Star with the 473rd.

Following war’s end Yarborough remained in the Army, which sent him to strife-torn Cambodia in 1956. His study of counterinsurgency operations there brought him back to Fort Bragg in 1961 as commanding officer, United States Army Special Warfare Center. In that assignment he won both promotion to brigadier general and the title “Father of Modern U.S. Special Forces” for his groundbreaking work to expand the American military’s unconventional operations capability.

Controversy continued to follow this colorful officer. Deliberately disregarding Army regulations, Yarborough and his command all wore green berets during President John F. Kennedy’s visit to the Special Warfare Center on September 25, 1961. Kennedy liked their look. Calling the green beret “a mark of distinction in the fight for freedom,” he directed Pentagon officials to authorize its exclusive use by Special Forces soldiers—men known ever since as the Green Berets.

William P. Yarborough reached the rank of lieutenant general before retiring in 1971. He died in 2005, a legendary figure within the elite fraternity of U.S. Army Special Forces and Airborne troopers. In his later years, Bill Yarborough examined the circumstances that led to his dismissal on Sicily.

“I deserved to be removed from command,” he once told an interviewer, reflecting on the emotional immaturity and pridefulness that led him to so inappropriately challenge authority. “You can’t have that kind of thing,” Yarborough concluded, “and I recognized where the deficiency lay. It was with me and not with Ridgway or Tucker.”

Fortunately, Bill Yarborough was given a second chance after his potentially career-ending confrontation with Maj. Gen. Ridgway. He thrived under other commanders, continuing on to eventually earn both three-star rank and a lasting reputation as one of the U.S. Army’s finest airborne and special operations officers. His influence is still felt in today’s armed forces.

Modern combat uniforms all have their origins in his multi-pocketed parachutist’s suit. And U.S. paratroopers still wear Yarborough-designed jump wings, often pinning them to a colored cloth oval he introduced in 1941. Airborne and Special Forces qualified personnel also take great pride in blousing their trousers over a pair of highly shined jump boots—footwear he developed.

Upon earning the coveted Special Forces tab, each new Green Beret is also presented with a combat knife to symbolize his membership in the brotherhood of unconventional warriors. This individually numbered blade is known throughout the special operations community as the Yarborough Knife. It honors a man who redeemed himself in the crucible of combat, growing wise from his mistakes while rising to overcome every challenge placed before him.

Patrick J. Chaisson, a frequent contributor to WWII History, is a retired U.S. Army officer and author from Scotia, New York.