By David Alan Johnson

Rear Admiral Willis Augustus Lee has been called, among other things, “one of the best brains in the Navy.” Although his critics and detractors had any number of unkind things to say about him, Admiral Lee had the ability to make quick decisions under the stress of battle and was certainly more technically minded than most officers of his age group.

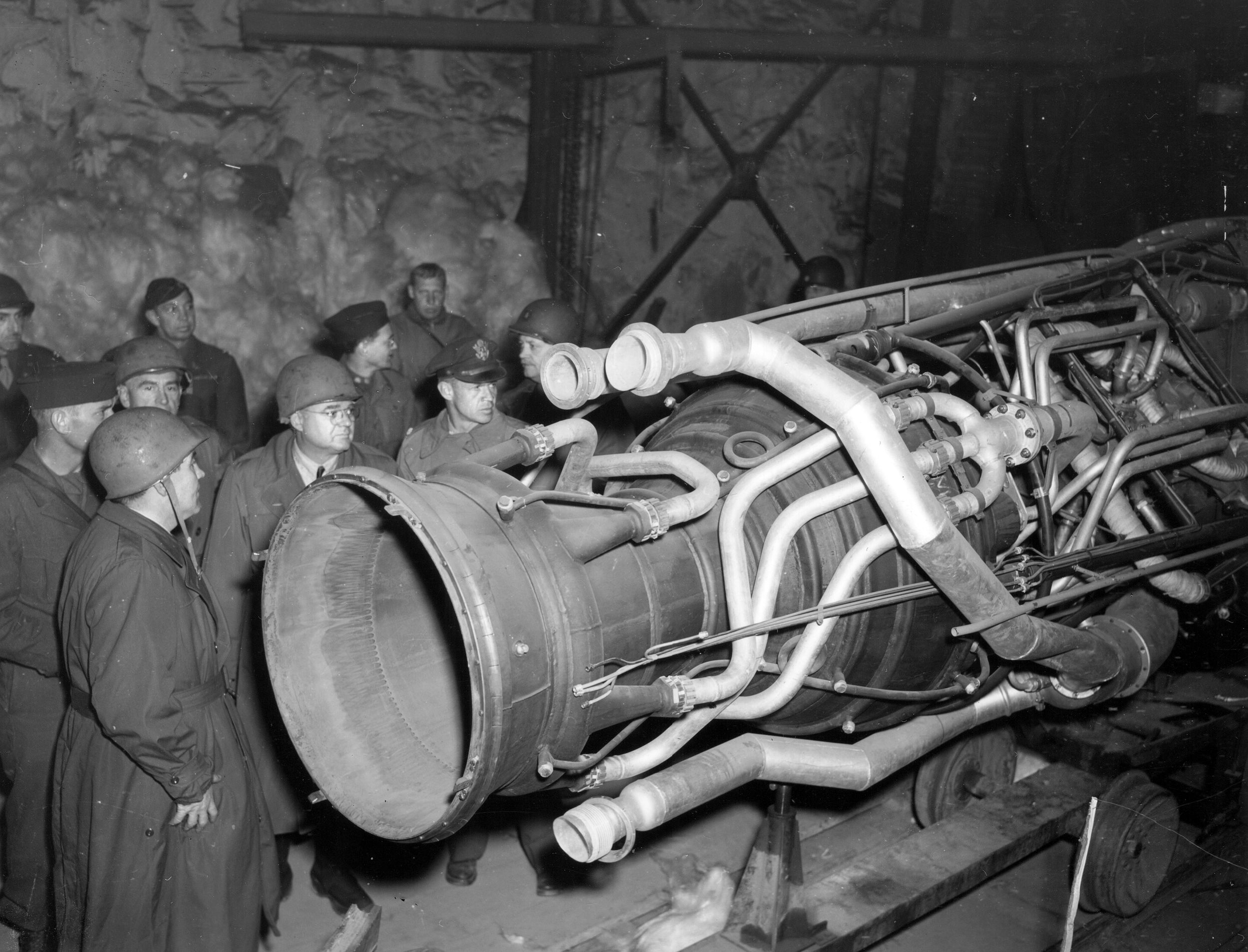

Lee had been director of fleet training between the wars and had been a major advocate of upgrading and modernizing U.S. warships. His special interest was in radar and the use of radar at sea. It was said that Admiral Lee “knew more about radar than the radar operators.” This knowledge, as well as his faith in the still largely untried and mysterious device, would prove to be indispensable on the night of November 14-15, 1942, in the waters north of Guadalcanal.

Admiral Lee and a six-ship task force had been sent to Guadalcanal by Vice Admiral William F. Halsey, overall commander of the South Pacific area, to block another Japanese effort to put Henderson Field out of operation. A task group of cruisers and destroyers under Admiral Daniel J. Callaghan had prevented Japanese cruisers and battleships from bombarding the airfield on November 13. The ensuing battle, the first phase of the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal, left Admiral Callaghan dead and six of his ships sunk. The survivors of this group were in no condition to stop another Japanese task force. Admiral Lee was given the job of stopping the latest enemy bombardment force with two battleships, Washington and South Dakota, along with four screening destroyers, a unit that had been designated Task Force 64.

During the afternoon of November 14, a Japanese reconnaissance aircraft discovered Task Force 64 steaming on a northerly course about 100 miles south of Guadalcanal. The pilot incorrectly identified Washington and South Dakota as cruisers accompanied by destroyers. At about the same time, a Japanese force under Vice Admiral Nobutake Kondo was discovered steaming south toward Guadalcanal. The American submarine Flying Fish came across Kondo’s force at about 4:30 pm and fired several torpedoes at the cruiser Atago. All of the torpedoes missed, but Flying Fish sent a plain language report regarding Admiral Kondo’s task group to Fourth Fleet intelligence. Admiral Kondo’s group consisted of the battleship Kirishimawith an escort of four cruisers and nine destroyers.

Thanks to the information from Flying Fish, Admiral Lee knew that he would be up against a large Japanese force. His own task force was approaching Guadalcanal’s western shoreline when he received the report. His six-ship column was led by four destroyers—Walke, Benham, Preston, and Gwin, in that order—followed by the battleships Washington, which was Admiral Lee’s flagship, and South Dakota. Admiral Halsey had given Lee permission to maneuver and position his ships as he saw fit. Admiral Lee decided to situate his task force just off the northwestern coast of Guadalcanal between Cape Esperance and Savo Island, where it would be able to intercept any Japanese force coming from the northwest.

Lee’s important advantage, gained by having been alerted that a Japanese force was approaching, was offset by the problem of never having worked with any of the accompanying ships in his task force before. The four destroyers were from four different divisions and had no division commander. The only reason that these particular destroyers had been assigned to Task Force 64 was that they had more fuel than any others in the area. And the two battleships had never operated together before, either. The six warships had only sailed together for the past 36 hours, during their run to Guadalcanal. To prevent any accidents during their first operational sortie, Lee ordered an interval of 5,000 yards between the destroyers and the two battleships. A collision in the restricted waters of Guadalcanal was the last thing he needed.

At about 9 pm on November 14, Lee ordered a 90-degree change of course, which would put his task force past Savo Island and into Ironbottom Sound. Before the war, that stretch of water was known as Savo Sound; that was the name given on all the charts. But sailors decided that so many ships had been sunk in this narrow strait since the invasion of Guadalcanal in August that its bottom must be lined with iron.

Admiral Lee knew that the enemy was on his way, but he badly needed more recent, and more specific, intelligence. His task force had departed the naval base at Espiritu Santo, New Hebrides, in such haste that it had not been given a radio call sign. When Lee tried to contact Guadalcanal—call sign “Cactus” —for any up-to-date information, he signed the communiqué with his last name. In response, he received the curt reply, “We do not recognize you!” The admiral decided to try again with another signal: “Cactus this is Lee. Tell your big boss Ching Lee is here and wants the latest information.” The “big boss” in question was General Alexander Vandegrift, commander of the 1st Marine Division and a friend of Lee’s since their Naval Academy days. “Ching Lee” was the admiral’s nickname when he was at the Academy (class of 1908).

Before General Vandegrift could be located, radio operators aboard Washington picked up some frightening talk between three nearby torpedo boats regarding Lee’s two battleships: “There go two big ones, but I don’t know whose they are!” The admiral thought it imperative to send some sort of message as quickly as possible, something containing some personal information that his friend Vandegrift would know, before the three PT boats fired their torpedoes at him. He decided to send another “Ching Lee” communiqué, which he knew Vandegrift would recognize immediately.

There are at least three versions of Lee’s signal to Vandegrift. The first, sent in a rhymed couplet, is the most colourful: “This is Chung Ching Lee—you mustn’t fire fish at me!” The second is an interchange between the admiral and the PT boats. “This is Lee,” he broadcast. “Who’s Lee?” came the response. “Tell your boss this is Ching Lee.” The PT boat’s response to this is not on record. Version number three is the most straightforward: “Refer your big boss about Ching Lee; Chinese, catchee? Call off your boys!”

The admiral’s colorful messages achieved at least one of their goals: they convinced the PT boats that the two “big ones” were not Japanese, and no fish were fired at Chung Ching Lee. But his requests did not supply him with any additional information regarding Admiral Kondo’s approaching force. Sometime after 10:30, “Cactus” responded, “The boss has no additional information.” For all of his lively radio messages with Guadalcanal, Lee was no better informed than he had been before.

While Lee was busy communicating with “Cactus,” Kondo split his 14 ships into three separate units. The light cruiser Nagara headed a six-destroyer column made up of Shirayuki, Hatsuyuki, Samidare, Inazuma, Asagumo, and Teruzuki. A column of three destroyers, Uranami, Shikinami, and Ayanami, along with the light cruiser Sendai, was sent off on a course that would take it east of Savo Island. The main bombardment group, which had been assigned to attack Henderson Field, consisted of the battleship Kirishima and the heavy cruisers Atago, which was Admiral Kondo’s flagship, and her sister Takao. Four troop transports, along with a screen of nine destroyers, were also approaching Guadalcanal. According to Kondo’s plan, the transports would land reinforcements for the Japanese garrison on Guadalcanal while Kirishima and the bombardment group shelled Henderson Field. The other two groups of cruisers and destroyers would deal with any American warships that came out to interfere with either the bombardment group or the landing of reinforcements. It was a plan that looked good on paper.

Sendai made first contact with Lee’s force at 10:10. Her radio reported, “Two enemy cruisers and four destroyers” northeast of Savo, heading toward Ironbottom Sound. Sendai and Shikinami changed course to pursue Admiral Lee’s force, and Admiral Kondo issued an immediate order to attack the American ships. Nagara and four of her escorting destroyers were also sent toward Ironbottom Sound at full speed. While his cruisers and destroyers were taking on the enemy, Kondo would bring Kirishima and his two heavy cruisers to the vicinity of Henderson Field to carry out their bombardment assignment.

Lee reached the southernmost limit of his course toward Guadalcanal at 10:52 and ordered a change of course to the right, steering his six ships due west. About eight minutes after changing course, Washington’s SG radar located an enemy ship about nine miles away and to the north—Sendai. Radar continued to track the cruiser until 11:12, when the main battery fire control director made visual contact. South Dakota also established visual contact, but none of the destroyers were able to spot the enemy cruiser. Four minutes after making contact by radar, Admiral Lee gave the order, “Open fire when you are ready.”

Washington held a vital edge over the Japanese task force: the new and efficient SG radar, which had proved itself vastly superior to the older SC search radar. SC radar had been introduced to American warships shortly before Pearl Harbor, in the autumn of 1941, and probably provided as many liabilities as benefits. Many senior officers blamed SC transmissions for giving away the positions of American ships to Japanese radar operators. Instead of allowing American warships to track the enemy, officers feared that the process was being reversed—Japanese ships were using SC emissions to track American vessels. But the newer, shorter wave SG radar produced no such doubts. Even officers who were almost totally ignorant regarding radar and its capabilities, who tended to be in the majority, were aware that SG radar represented a vast improvement in technology over the old SC sets.

At 11:17, about 17 minutes after the first radar contact, Washington’s 16-inch batteries opened fire on Sendai and her escorts. Her 5-inch guns fired star shells to light up the Japanese column. The 16-inch shells landed in the vicinity of and her escorts, which were 18,000 yards to the north, but none of them scored hits. South Dakota’s radiomen could hear excited Japanese voices jabbering away at each other. A short while later, Admiral Shintaro Hashimoto, commander of Sendai’s task group, turned to the north with the destroyer Shikinami behind a smoke screen. Washington’s radar operators were able to track the Japanese ships in spite of the smoke.

Admiral Hashimoto’s other two destroyers, Uranami and Ayanami, continued to steam southward toward the American column. The destroyer USS Walke, at the head of Lee’s column, opened fire with her 5-inch guns at 11:23, followed shortly by “rapid gunfire” from Benham and Preston. About four minutes after Walke began firing, Gwin discovered the cruiser Nagara and her destroyer screen. For the next several minutes, Gwin became involved in what has been described as “a private gun duel” with the Japanese warships.

It did not take long for the Japanese to begin returning fire. Nagaraand her escorting destroyers hit Preston several times, putting her boiler room out of action and toppling her after stack. Other shells, probably from Nagara, hit the engine room and turned the area surrounding the aft gun mounts into “a mass of blazing red-hot wreckage.” The gunnery officer tried to keep the forward guns firing, but Preston was already beginning to sink, settling by the stern and listing to starboard. The order to abandon ship was given at 11:36, roughly 14 minutes after Walke had opened fire. Less than a minute later, according to the destroyer’s survivors, Preston rolled over on her starboard side and went down. Crewmen aboard Gwin, about 3,000 yards astern, watched as their sister destroyer was being pummelled by enemy gunfire. Gwin had to make a hard turn to starboard to avoid colliding with the sinking wreckage.

The Japanese warships were partially concealed by the dark gray backdrop of Savo Island. The ships also made good use of flashless powder, which helped to conceal their positions. Even though their gunfire had been extremely accurate, the primary Japanese weapon was the Type 93 Long Lance torpedo, which was about to inflict more damage to the unfortunate American destroyers.

The Long Lance was the bogeyman of American warships. Everything about it was impressive, including its size—30 feet long and 24 inches in diameter. Its maximum range was an incredible 22,000 yards (11 nautical miles) at a speed of 49 knots; it carried a warhead of 1,180 pounds. By comparison, the U.S. Navy’s Mark 14 torpedo had a range of 6,000 yards at 45 knots, with a warhead of only 825 pounds. The Long Lance was also oxygen-fuelled, as opposed to air-fuelled, which left an almost invisible wake and allowed it to travel faster and farther. The Imperial Navy equipped its cruisers and destroyers with the Long Lance, which were launched from 24-inch tubes that were mounted on deck. The tubes could be quickly reloaded, which essentially doubled the number of torpedoes that could be brought to bear on enemy ships.

The destroyer Ayanami launched her Long Lances at 11:30 pm; the others fired theirs about five minutes later, before making a turn to port. At about 11:38, one of the torpedoes, probably from Ayanami, struck Walke. The explosion of the warhead was intensified by the detonation of the forward magazines; everything forward of the bridge was blown clear of the rest of the hull. Power and all communications instantly failed throughout the ship, and Walke sank bow first. As she went down, her depth charges exploded, killing several of the survivors in the water.

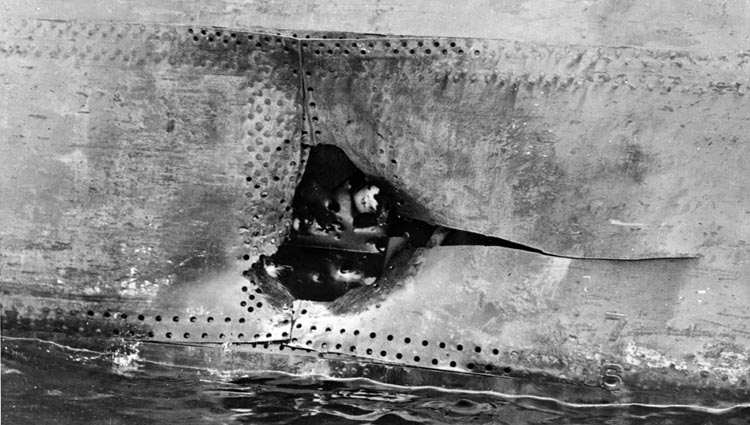

Another torpedo struck Benham at the forward extremity of her hull. The explosion blew a large hole in her bow but did not sink her. After executing an evasive maneuver to avoid enemy gunfire, Benham returned to her original course at a speed of 10 knots—reduced in speed, but still afloat. Gwin’s turn to avoid Preston probably allowed her to escape the enemy torpedoes, although she was hit by three shells. One of the hits damaged her torpedo safety links, which allowed the torpedoes to slide harmlessly out of their tubes and into the sea.

The damage had not been completely one sided. Ayanami’s gunfire had given away her position—her muzzle flashes were clearly visible against the dark gray silhouette of Savo Island.Washington opened fire on the Japanese destroyer and hit her several times, setting her alight and leaving her dead in the water. Her sister destroyers had been more fortunate. None had been damaged, and all of them remained in the fight with torpedo tubes reloaded.

The four destroyers of Admiral Lee’s column had not been nearly as lucky. Preston and Walke had been sunk; Benham and Gwin were badly damaged but still afloat. They had taken “the brunt of the fighting,” according to one writer, but they had also done their job. As the escorts for South Dakota and Washington, they had protected the two battleships from enemy gunfire and torpedoes at a great cost to themselves. At about 11:48, Admiral Lee ordered Benham and Gwin to withdraw from the battle area. The battleships were now on their own.

But even before the two destroyers left the area, South Dakota experienced what has been politely described as “a stroke of bad luck” —the ships electrical circuit breakers “jumped out.” Immediately, to the frustration of everyone on board, all lights failed and all radar screens went dead. “The psychological effect on the officers and crew was most depressing,” as understated by the South Dakota’s captain, Thomas L. Gatch. “The absence of this gear gave all hands the feeling of being blindfolded.” The battleship’s lights were out for only six minutes, from 11:30 to 11:36, but when power was restored, the ship’s radar operators discovered that their radar picture was “incomplete—radar was back, but it was not working to full capacity. “The SG radar was inoperative,” as stated by the official damage report, “which complicated station-keeping and detection of new targets.”

To make matters worse, South Dakota had turned to starboard instead of port when avoiding Preston and Walke, which put her squarely between the burning destroyers and the Japanese warships. The battleship was now silhouetted by the fires, making her an inviting target for Japanese gunners and torpedo crews. When radar came back, operators were startled to find enemy warships—Admiral Kondo’s bombardment group—less than three miles away. Kondo did not spot South Dakota until 11:58. Several of his ships, including Atago and Asagumo, fired their torpedoes at the battleship, and Atago turned her searchlights on her. At this point, lookouts positively identified South Dakota as a battleship. Previously, she had been reported as a cruiser. But now, with her towering foremast and massive superstructure brightly lit up by Japanese searchlights, there could be no doubt as to South Dakota’s true identity.

All the torpedoes missed, but the gunfire certainly found its mark. In the space of about four minutes, just after midnight, South Dakota sustained 26 hits. The ship’s gunfire report specified, “It is estimated that one hit was 5-inch, six were 6-inch, eighteen were 8-inch, and one was 14-inch.” Another report states, “The ship was badly cut up topside by 6- and 5.5-inch shells, although the armor had withstood two 14-inch hits.” Several of the shells did not explode. A sailor aboard South Dakota recalled that an exploding shell sounded like “a loud crash, a rolling explosion,” followed by “the sizzling sound that metal fragments make when they crash into cables, guns, and the superstructure.”

“In spite of numerous hits,” the official report concludes, “South Dakota received only superficial damage. Neither the strength, buoyancy, nor stability were measurably impaired.” Kirishima’s assistant gunnery officer had a much more optimistic assessment of the situation. “We think we hit the South Dakota many times,” he said, “inflicting much damage.”

Damage control parties put out fires and performed emergency repairs as best they could, working around wreckage in every department along with 39 bodies of their fellow crewmen. Captain Gatch came to the conclusion that his ship was no longer in any condition to assist Lee in stopping Kondo’s bombardment group and asked permission to withdraw from the battle area. At 12 minutes past midnight on the morning of November 15, Admiral Lee gave his permission.

With South Dakota safely out of the vicinity, Washington now faced Kondo’s warships all alone. In the words of historian Samuel Eliot Morison, she became “a lone-ship task force.” This should have put Lee and his flagship in a precarious position. But the lookouts in Kondo’s force had become so preoccupied with South Dakota that no one seemed to notice Washington, only about 8,400 yards away. South Dakota was already under fire, was brilliantly lit up by searchlights, and had suffered a good many hits. “In Kondo’s ranks, there was a general rush to get the brightly illuminated South Dakota,” said one writer. Admiral Lee recognized his incredible good luck and prepared to open fire on Kirishima, the fattest target in Kondo’s task force.

A British writer romantically described the fight between the German battleship Bismarck and the battlecruiser HMS Hood, which had taken place a year and a half earlier, as a joust between two medieval knights “with guns for lances and armored bridges for visors and pennants streaming in the wind.” The battle between Washington and Kirishima was more like a bout between two heavyweight boxers in a blacked-out ring. Washington’s SG radar gave her a great edge, but one of her 5-inch guns also sent up a star shell to illuminate Kirishima and to give her lookouts a better visual contact. Washington’s radar was humming accurately and giving her a good picture of the enemy, but her radar operators were also confronted with a touchy technical situation. South Dakota was tucked away in the radar’s blind spot on her starboard quarter, and Washington could not see her sister ship on any of her radar screens. Lee was afraid that the fattest target on his SG might be South Dakota and feared that he might be shooting at one of his own ships. When South Dakota was safely accounted for and the admiral was assured that his sister ship was actually behind him, he gave the order to open fire.

While two 5-inch turrets fired at Atago, all nine guns of Washington’s 16-inch main battery, along with two of her 5-inch mounts, let loose at Kirishima at exactly midnight. The battleship’s gunnery officer officially noted that Washington opened fire at the target, which he described as “a Kongo battleship,” at a range of 8,400 yards. All guns were loaded with armor-piercing ammunition, which was designed to penetrate Kirishima’s decks and explode inside the hull. Admiral Kondo’s ships, on the other hand, were firing explosive shells with impact fuses, which were meant for destroying the shore facilities at Henderson Field and inflicting casualties among troops. The inability to cause more damage to South Dakota was due to the fact that the wrong ammunition was used against the battleship.

Washington’s shells rocketed toward Kirishima at speeds in excess of 2,600 feet per second. To the men aboard the Japanese battleship, the muzzle flashes of Washington’s guns must have been frightening—they knew that the big American shells were in the air and were heading straight for them. Less than a minute later, Kirishima was all but hidden from view by the splashes of exploding shells; great geysers of white water shot high into the air, higher than Kirishima’s superstructure, all around the ship. But not all the shells were near misses. Washington’s gunnery officer noted, “Fire was opened at 8,400 yards and a hit was probably obtained on the first salvo and certainly on the second.”

Kirishimawas hit repeatedly, by both 16-inch and 5-inch shells. Several fires were started deep within her hull as well as in her superstructure, two of her main turrets were put out of action, her steering apparatus was jammed, and she was also hit below the waterline, causing severe flooding in several compartments. “It is of interest to note that … ‘overs’ as well as ‘shorts’ could be seen optically,” reported Washington’s gunnery officer. “Salvos were walked back and forth across the target.”

Although target tracking was done optically, radar was largely responsible for Washington’s excellent shooting. “On the second main battery, target tracking was done entirely by radar for at least five minutes,” the same gunnery officer said. “When the target finally came into view optically, checks given by the pointer indicated that the radar was exactly on.” Admiral Lee, who had been preaching the practical virtues of radar since it had first been introduced to the fleet, was greatly satisfied with this report. It supported everything he had been saying about this new and mysterious device that allowed gunners to see their targets in the dark and regardless of the weather.

“Within seven minutes, Kirishima was out of the fight,” a naval historian recounted, with “steering gear hopelessly wrecked, topsides aflame.” Kirishima’s assistant gunnery officer gave a more detailed account of the battleship’s predicament. “Shortly after the American ships opened fire,” he said, “the steering of the Kirishima was so badly damaged that we were unable to steer or repair it. We kept turning in a circle but couldn’t get away. We slowed down to try to steer with the engines but it was no use. Our engines were not badly damaged, but we were receiving many hits from the Washington.” He went on to say, “We received about 9 x 16 hits and about 40 x 5 hits”—nine hits by Washington’s 16-inch guns and 40 by her 5-inch batteries.

At seven minutes past midnight, exactly seven minutes after opening the battle with Kirishima, Washington ceased firing. Admiral Samuel Eliot Morison’s assessment agrees with that of Kirishima’s assistant gunnery officer: “Nine out of 75 sixteen-inch shells from Washington scored, as did about 40 fast-shooting 5-inchers.”

Admiral Kondo’s bombardment group was still a force to be reckoned with, even though Kirishima was now out of the battle. Atago and Takao, along Nagara and Sendai, as well as about a half-dozen destroyers from Kondo’s two support groups, were still in the area west of Savo Island. But Kondo was concerned over the safety of his transports, so he ordered the bombardment of Henderson Field aborted and detached several destroyers to attack Washington. The American battleship had changed course to the north-northwest about 13 minutes after she stopped shooting at Kirishima; Admiral Kondo was determined to keep her from interfering with the troop transports. At about 12:40, the destroyer Oyashio fired her torpedoes at Washington; about six minutes later, Samidare also fired her Long Lances. Atago added three torpedoes of her own. All of them missed their mark, although lookouts reported that some of the torpedoes came “uncomfortably close.”

Kondo was having second thoughts about attacking Washington and reached the decision that it was no longer viable to remain in the vicinity of Savo. At 12:45, he ordered all ships not actively engaged in the attack to withdraw, and all ships attacking Washington to retire after firing their torpedoes. At about 12:35, Kondo’s bombardment force retired from the waters off Savo Island behind a dense smokescreen. “Admiral Lee observed this move with satisfaction,” as understated by Admiral Samuel Eliot Morison. But before withdrawing, in a final gesture of defiance, two destroyers, Kagero and Oyashio, launched torpedoes at Washington. At least two of them exploded when they encountered the turbulence of the battleship’s wake.

Washington was the last American warship to leave the battle zone. South Dakota had already been out of the area for about 15 minutes. The destroyer Gwin was escorting Benham back to Espiritu Santo, but the noseless destroyer was too badly damaged to complete the journey. On the afternoon of November 15, Gwin removed Benham’s crew and prepared to scuttle the crippled destroyer with a spread of torpedoes. All four torpedoes either missed or malfunctioned. Gwin finally sank her sister destroyer with gunfire and reached Espiritu Santo without further incident. South Dakota also arrived at Espiritu Santo accompanied by Washington. Because of the damage that had been inflicted to her superstructure, South Dakota returned to the United States for refitting, where she received an overhaul and complete repairs of all battle damage.

The Japanese destroyer Ayanami suffered the same fate as Benham, except Ayanami did not have to be scuttled. Uranami removed Ayanami’s crew and watched the destroyer sink at around 2 am. Kirishima was still afloat at this time, but was barely making headway and still taking water through the shell holes below her waterline. The battleship’s assistant gunnery officer recalled, “The captain decided that since we couldn’t steer and the engines were damaged, it would be better to scuttle the ship. He then gave the order to open the Kingston valves.”

After the Emperor’s portrait was transferred to the Asagumo, and as the sea valves were opened, Kirishima slowly settled into the waters west of Savo Island. “It took about two and one-half hours to sink,” the same officer recalled. “Destroyers came alongside and took off about one quarter of the men. The rest of the men jumped over the side and were later picked up by destroyers. We had about 1,400 men on board and lost about 250.” The battleship finally went down at 3:25 on the morning of November 15.

In the summer of 1992, nearly 50 years after her battle with Washington, underwater explorer Robert Ballard discovered the wreckage of Kirishima about 11 miles west of Savo Island. Dr. Ballard found that the ship had turned completely upside down on her way to the bottom and that her superstructure had jammed itself into the mud. Only the bottom of the ship’s hull could be seen, with her propellers and rudders visible above the keel. It is probable that the battleship’s tall pagoda mast made her top-heavy and caused her to turn over after she had gone down. Dr. Ballard also noticed that Kirishima’s bow had broken off, suggesting that her forward magazine had blown up sometime after sinking.

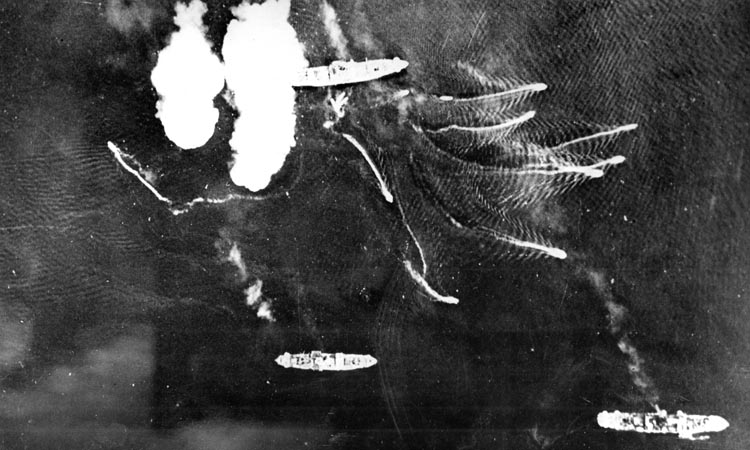

Even though the warships of both sides had gone back to their respective bases, the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal was not quite over. The four transports of the reinforcement group were ordered to run themselves aground on the northern coast of Guadalcanal. After running up on the shore, the ships would land their troops on the beaches, and then the soldiers would join Japanese units already on the island. Kondo had not succeeded in shelling Henderson Field. Hopefully, the commander of the reinforcement ships, Admiral Raizo Tanaka, would be able to put his troops ashore and accomplish at least one of the task force’s assigned goals.

By 4 am, all four transports—Sangetsu Maru, Yamura Maru, Kinugasa Maru, and Hirokawa Maru—had run themselves up on the beaches near Tassafaronga. But shortly after sunrise, the air group from the carrier Enterprise, along with fighters and bombers from Henderson Field, began bombing and strafing the ships. They continued their attacks until about 3:30 in the afternoon. The transports were decimated by the air attacks, which were assisted by gunfire from the destroyer Meade. The water off Tassafaronga was covered with blood and dead bodies. Only about 2,000 soldiers reached the shore, along with about 260 cases of ammunition and 1,500 bags of rice.

Both sides claimed a “tremendous victory” as a result of the fighting on November 14-15. Some Japanese sources claimed eight American destroyers sunk. Others mentioned two battleships either sunk or damaged. American claims were just as inflated: several cruisers sunk, along with a number of destroyers and one battleship. The actual numbers varied according to which source was consulted. But though Lee lost three of his four destroyers and had one of his battleships badly shot up, he had stopped Kondo from shelling Henderson Field as well as from reinforcing Japanese troops already on Guadalcanal. In addition, he sank Kirishima and one destroyer.

The outcome of the battle also gave Japanese leaders their first misgivings about the possible end of the Guadalcanal campaign, as well as the war itself. They knew that they could not replace warships or transports the way the Americans could. “The Imperial Army did not give up Guadalcanal for another ten weeks,” an American historian wrote, “but the Navy performed its ferryboat duties with increasing reluctance and made no further bid to rule the adjacent waves.”

Admiral Lee had no doubts in his mind that he had won the battle, but he also knew how he managed to win. He later wrote, “We … realized then, and it should not be forgotten now, that our entire superiority was due almost entirely to our possession of radar. Certainly we have no edge on the Japanese in experience, skill, training or performance of personnel.”

Author David A. Johnson has written for WWII History magazine on a variety of topics. He is also the author of numerous books on subjects ranging from the Civil War to World War II. He resides in Union, New Jersey.