By Christopher Miskimon

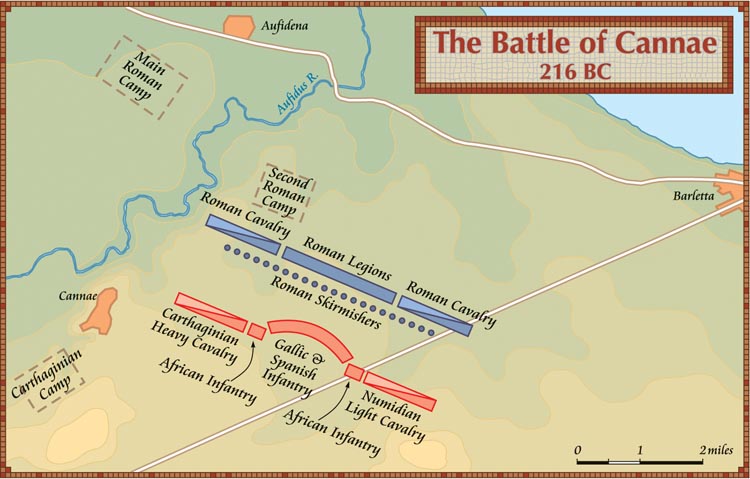

Long ranks of Carthaginian infantry stood on a dusty plain a few miles east of the ruined town of Cannae on August 2, 216 bc. Cavalry massed at each end of the Carthaginian line stood poised to harass the enemy’s flanks. Opposite the Carthaginians, a Roman army was arrayed in similar fashion.

The day was warm, dry, and windy. A seasonal wind known as the libeccio, which blew from the south, sent fine particles of dust into the faces of the advancing Romans. The armies had deployed from their camps north of the River Aufidius to the south side of the twisting waterway.

As combat grew near, many of the Carthaginian troops gripped Roman weapons that they had picked up from a clash at Lake Trasimene the previous year. More than a few wore similarly looted Roman armor. They carried Roman javelins, spears, and gladii. None of them had seen their native lands for many years. Indeed, the only way they might ever see those homes again was to achieve yet another victory. Although outnumbered and deep in enemy territory, their confidence remained high.

The Carthaginian troops had complete faith in their stalwart leader, Hannibal Barca. Hannibal had proved that he was brilliant, bold, and daring. Upon the fields surrounding Cannae that day Hannibal’s name would become deeply etched in the annals of history. What Hannibal would achieve at Cannae would forever mark him as one of the greatest battlefield commanders of all time.

Rome and Carthage had previously gone to war against each other in the First Punic War that began in 264 bc. Over the course of the 23-year conflict, the Romans gradually wrested control of Sicily from the Carthaginians. The Carthaginians, who retreated to the western part of the island, could no longer sustain themselves when the Romans destroyed their fleet in the Aegates Islands in 241 bc. Rome ejected the Carthaginians from Sicily and forced them to pay a heavy indemnity at the peace table.

The Romans emerged from the First Punic War as the dominant naval power in the Mediterranean Sea. Afterward, the Carthaginians began to rebuild their military forces in anticipation of a new war. To finance their armies and fleet, the Carthaginians embarked on a concerted effort to expand economically.

Hamilcar Barca, one of Carthage’s leading generals, masterminded the Carthaginian occupation of Iberia. It took decades and a generation of the Barca family, but by 218 bcCarthage was ready to exact revenge against Rome. The job fell not to Hamilcar, but to his son, Hannibal. When Hannibal was only 10 years old, Hamilcar made him swear an oath of eternal enmity toward Rome.

Hannibal was an astute commander who knew how to inspire men. He once swam a river to encourage his men to follow and slept on the ground as they did. Ready for a rematch with Rome, Hannibal attacked the Iberian city of Saguntum after its leaders chose to ally with Rome. The incident touched off the Second Punic War.

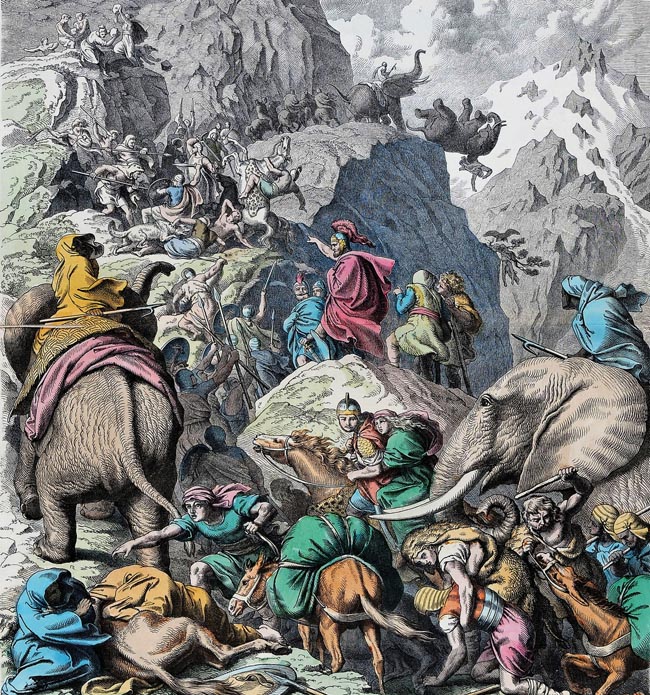

Seizing the initiative, Hannibal led his army north. The Carthaginians crossed the Alps and invaded the Roman heartland with 46,000 troops and 37 elephants. Hannibal recruited Gauls and others enemies of Rome as he marched.

The Romans responded with their legions, each accompanied by another legion raised by a Roman ally in the region. Hannibal’s generalship brought the Romans low at Trebia in 218 bcand at Lake Trasimene in 217 bc. Rome suffered heavy casualties and damage to its reputation from these defeats.

The Romans needed to turn the tide. For that reason, they appointed Quintus Fabius Maximus as dictator. Fabius realized his best option was to create time to rebuild the Roman armies, so he avoided pitched battles and sought smaller skirmishes designed to weaken the Carthaginians gradually while building his own strength. While the strategy was reasonable given the situation, it did not sit well with Roman leaders. Rome had a tradition of aggressive military action and their mind-set precluded anything other than the offensive.

The Romans subsequently elected two consuls, Lucius Amelius Paullus and Gaius Terentius Varro. Meanwhile, the Roman Senate authorized the expansion of the Roman army by four legions along with four allied legions. These would join with two existing armies led by the previous year’s consuls, Marcus Atilius Regulus and Gnaeus Servilius Geminus. Regulus would be replaced before the battle by Marcus Minucius Rufus. These existing armies shadowed Hannibal’s force while it wintered in Geronium in southern Italy.

The Roman plan was simple. Paullus and Varro would each command the army on alternating days, a Roman custom of the time. They would rendezvous with the two armies in the field and take command of the entire force. Their objective was to bring Hannibal to battle and defeat him, thereby ending the Carthaginian threat. The alternating command may have been Roman tradition, but Paullus and Varro disliked each other and were frequently at odds. Thus, the Roman army had a significant leadership problem.

The two armies were organized and equipped according to their own customs and heritage. The Roman legions were raised by the legio, a levy of citizens ranging from 17 to 49 years of age, who owned property. Rome had a long martial tradition and propertied families were accustomed to military service, training their sons for it. In addition, each Roman ally was expected to raise its own legion to join the Romans on a one-for-one basis. It is believed these units were organized similarly to the Roman legions. During the Second Punic War the legions were raised for a period of one year with new troops rotated through them, so these units began to become permanently established organizations.

Each legion was 4,500 strong with 4,200 infantry and 300 cavalry. By this time the legions were organized into the triplex acies, a system of three lines. The first line was the hastati, 1,200 younger men armed with the pilum, a Roman javelin, and the gladius, a short sword. They also carried a large shield called a scutum and wore a helmet and chest armor. The second line consisted of the principes, another 1,200 men considered in their prime. They carried similar arms and armor to the hastati though some may have worn mail coats called lorica hamata. The third line held the triarii, 600 experienced older men who also carried spears. Each legion also had 1,200 velites, light infantry who would screen the legion and act as skirmishers. These men probably did not wear armor but carried a light shield, a few javelins, and a gladius. These lines would stagger to cover gaps, which also allowed the cavalry or velites to move through the formation more easily.

The wealthiest Romans made up the cavalry. Known as the equites, they guarded the flanks and pursued fleeing enemy soldiers. The 300 horsemen of a legion were divided into 10 turmaes of 30 men each, all well armed and armored. Generals often positioned themselves with the cavalry. In all a well-trained legion was a formidable unit led by trained leaders, the entire force steeped in the militaristic Roman tradition. One flaw of the legions present at Cannae was a lack of training. They were hastily raised and sent into battle before they could be seasoned. The troops also were raised from a wider group due to the desperate need for men after the previous defeats. The property requirements were eliminated, which meant many of the recruits lacked the martial training the wealthier men received.

The Carthaginian army followed different practices based on Carthage’s multicultural nature and experiences. Carthage did not have Rome’s population base and historically paid more attention to its navy. Their society was largely an oligarchy and the army reflected that quality. The Carthaginians drew troops from the various provinces and allied states to round out their army. The army contained a small core of citizen-soldiers surrounded by larger numbers of the allied troops and mercenaries recruited through Carthage’s extensive trading networks. The polyglot Carthaginian army was composed of Carthaginians, Numidians, Libyo-Phoenicians, Iberians, and Gauls. The Carthaginian cavalry at Cannae consisted of Numidians, Iberians, and Gauls. The senior officers were Carthaginians and were drawn from the city’s leading families.

Rather than try to train and organize these disparate factions along a common line, each contingent was allowed to fight according to its native traditions. This allowed the various groups to maintain their cohesion in battle, remaining at the side of their tribal comrades. They also used whatever equipment was familiar to them; however, as the campaign stretched out over the years much of the original equipment had to be replaced.

In combat, the Carthaginian infantry often would form into side-by-side columns to help maintain cohesion. This formation mitigated the differences in fighting techniques of the various contingents. These columns contained the Gauls and Iberians in alternating blocks with the Libyo-Phoenicians anchoring them on both ends. In front of this line of columns were the light infantry, which was composed of Balearic slingers and Celts. Four thousand Gallic horsemen were present in the Carthaginian army at the time of the battle. Like the Romans, they took their place on either end of the infantry formation, prepared to screen or charge as needed.

For this mixed formation to succeed, Hannibal had to understand how each contingent worked in order to make the best use of them. He also commanded the respect of the various leaders, who trusted his orders. It was a highly complex arrangement requiring intelligence, planning, and foresight. Luckily for the Carthaginian army, Hannibal possessed these qualities in abundance. He knew how to get the most from each group. He also had a handful of trusted generals. These were his brothers Hasdrubal and Mago, Hasdrubal Gisco, Maharbal, and Masinissa.

Hannibal’s army was experienced and confident; the army’s recent victories had boosted its morale considerably. The army functioned well, with the senior leaders controlling the disparate sub-units under Hannibal’s overall control. Hannibal also knew once battle was joined his influence over events was limited, so he engaged in extensive planning beforehand so his men knew exactly what to do.

While Paullus’s and Varro’s armies prepared to march, Hannibal’s army left its winter quarters at Geronium and moved toward Cannae in June 216. This was a deliberate move as the ruined fortress at Cannae was a grain and food storage site serving the entire region. Occupying the area threatened food production for the whole area, something the Romans could not ignore without appearing helpless in front of their local allies. If the Romans did respond, Hannibal would get the battle he wanted. Regardless of whether the Romans appeared or not, the Carthaginians gained. In the interim, they could nourish themselves on Roman food.

The Roman armies of Atilius and Servilius shadowed Hannibal. Word soon reached Rome that he was at Cannae. Paullus and Varro hurriedly finished their preparations and marched out in late June. The entire Roman force rendezvoused about two day’s march from Cannae, only about four months after Paullus’s and Varro’s election as consuls. It was a noteworthy accomplishment considering that Rome had never before fielded such a large army.

The Romans advanced toward Cannae and made camp five miles away, within sight of their opponents. Paullus and Varro succumbed to arguing. Paullus worried that the broad, flat plain was perfect for the cavalry actions at which the Carthaginians excelled. But Varro vehemently disagreed. As the two were alternating command each day, Varro soon had the chance to dispatch a reconnaissance in force to better ascertain Hannibal’s position. The Carthaginians responded with cavalry and light infantry and a sharp skirmish ensued. The Romans suffered initial reverses but quickly recovered, reforming their lines. They drove the Carthaginian troops steadily back until nightfall put an end to the fighting.

This was a good initial success for the Romans, but the advantage was squandered the next day when Paullus took command. He refused to launch a followup foray; instead, he split the Roman army and set up a new camp on the other side of the Aufidius River. By doing so, Paullus hoped to better protect the Roman foraging parties while menacing the Carthaginian foragers.

Sensing the approaching battle, Hannibal gathered his troops and gave a speech. He told them he had no need to ask for their bravery because they had shown it three times already in previous battles since arriving in Italy. Hannibal further reminded them of all they had achieved since then. “He who will strike a blow at the enemy—hear me!” said Hannibal. “He will be a Carthaginian, whatever his name will be, whatever his country.” The speech worked, encouraging the entire army about the battle to come.

The next day Hannibal likewise established a second camp on the other side of the river. Paullus was in command and made no response, keeping his army in its own camp. He believed he could wait out Hannibal, not wanting to fight in that location. Soon enough, Hannibal’s supplies would grow low and he would have to march. Some Romans did come out to collect water, and Hannibal dispatched a group of Numidians to harass them. This angered Varro and many in the Roman camp. The situation was bound to change the next day, though, when command of the army switched.

Varro took charge the following morning. He assembled the entire army at dawn on the south side of the river. The Romans drew up into their battle formation facing south toward the Carthaginians. Hannibal had purposely placed his troops generally facing north so that the libeccio blew dust into the Romans’ eyes. The combined legions possessed 40,000 Roman infantry, 40,000 allied infantry, and 6,400 cavalry. Varro detached 10,000 infantry from the main force to remain at the camp, leaving 76,400 to engage the Carthaginians.

The Roman line was organized with each of the four consular armies in line next to each other. The infantry closed up so that they presented a narrower front with more depth to their ranks. This may have been due to the inexperienced men in the two newest armies, who lacked the training and experience to maneuver well in the standard formation. This was not necessarily a bad arrangement, but with the armies of Paullus and Varro on the outside edges of the line, it meant the least experienced troops manned the flanks.

The Roman cavalry took position on the right end of the line, anchored on the river. The allied horsemen deployed on the left end of the line. The light infantry screened the front of the line. Paullus went with the Roman cavalry on the right while Varro was with the Allied cavalry on the left. The two previous consuls stood in the center with their respective armies.

The 50,000-strong Carthaginian army was composed of 50,000 infantry and 10,000 cavalry. Hannibal deployed his light infantry, both slingers and spearmen, to screen his army as it crossed the river. Once across the river, Hannibal anchored his left wing on the river, placing 6,000 Iberian and Gallic cavalry on the extreme left flank under the command of Hasdrubal. On the extreme right flank were 4,000 Numidian cavalry led by Maharbal. The Gallic-Iberian heavy infantry stood in the center, with Libyo-Phoenician heavy infantry on each side. The Roman army had the greater number of men, but Hannibal’s army was more experienced and had an impressive number of victories to its credit.

The Carthaginian line advanced at Hannibal’s command, with the center slightly forward so the entire line was shaped like a crescent with the depth of the line thinning out near the edges. Hannibal’s line looked mismatched as it marched forward, the Iberians in their linen tunics interspersed with the Gauls, many of whom went into battle shirtless. All of them used large oval shields as protection. It was a polyglot force but it moved well in unison.

The opposing light infantry started the battle. The Balearians used their slings, covered by the spearmen. The Roman velites and their allies fought back and the fighting broke down into a number of small, inconclusive skirmishes all along the space between the two armies, not unusual in ancient combat. Being lightly armed and armored, the light troops in the screens could not last long even against each other and soon they fell back.

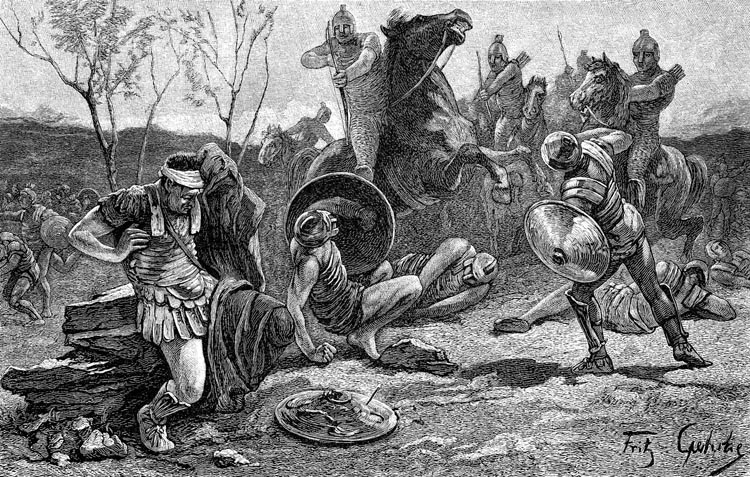

Hasdrubal’s Iberian and Gaulish cavalry charged in what Roman historian Polybius deemed “true barbaric fashion,” advancing along the bank of the river toward the Roman horsemen. It was a narrow front, with the river on one side and the infantry on the other, allowing neither force any room to maneuver. Normally, cavalry in ancient times would attempt to outflank by riding around the other force or by making feints. But the constricted space precluded those kinds of maneuvers.

The two groups rode straight into each other. The opposing horsemen were tightly packed. The horses often could not move and many simply stood still next to each other while their riders hacked and slashed at nearby enemies. Some fought so closely they grappled each other off their mounts and had to continue fighting on the ground. At first the Romans managed to put up a spirited resistance, but the violence of the Carthaginian charge took its toll in Roman casualties. Soon the Romans broke and retreated back along the river bank, the only way they could go in the close quarters. Hasdrubal ordered his horsemen to give chase and they pursued, sparing no one. Paullus managed to escape with a small contingent of bodyguards and rode to the center of the Roman line.

As the Roman right-wing cavalry fled in disorder, the infantry made contact. The legions in the Roman center crashed into the Carthaginian center, which was slightly ahead of the rest of their line. Paullus realized the battle was up to the infantry and took position where he thought he could do the most good. He shouted words of encouragement to his men, urging them forward. Each side sought to gain an advantage with its weapons. Men screamed and died, their flesh torn and yielding despite the armor they wore.

At first the Carthaginian soldiers held, fighting well despite their national and tribal differences. The Iberian and Gaulish ranks were too few, leaving their line thin and without the depth needed to maintain their defense. The legions packed their line more densely and now that depth told, forcing the Carthaginians back. Soon their bulging convex line turned into a concave one just as the Roman line now became a wedge. As that wedge grew deeper the Romans on the ends of the line started to draw in toward the center and pushed even harder toward the apparent weak spot in Hannibal’s line. These were the novice troops of Paullus’s and Varro’s armies.

The legionaries kept up the pressure as the Carthaginian center began to retreat. The Roman flanks soon drew in toward the center far enough that they were even with the Libyo-Phoenician infantry positioned to either side of the Iberians and Gauls. Now came a crucial point in the battle. The contracted Roman line focused on the center, where at long last success over Hannibal seemed imminent. This left the flanks vulnerable. Hannibal saw this and took advantage of the situation. The Libyo-Phoenician infantry wheeled toward the shortened Roman flanks and charged in at them, fresh troops crashing into the tightly packed legionaries, many of whom were already tiring from pushing against the center.

Still, the battle was not yet over. The Romans must have kept their discipline, reforming their ranks to deal with the new threat. Such actions would have been hasty and extremely difficult, given the lack of space for the Roman soldiers to maneuver, for as they advanced toward the center they naturally pressed together. Yet the battle was not entirely lost at this point, so the Romans must have succeeded in quickly creating a defensive line in the constricted space. This did leave each individual with less room to use his weapon or position his shield. The Roman line remained coherent but its forward momentum was likely checked, allowing the battered Carthaginian center a brief but crucial reprieve.

While the Roman infantry realigned to deal with this new and dire situation, the 4,000 Numidian horsemen took advantage of the change in fortune to charge at the Roman allied cavalry on the Roman left wing. Varro remained with these Allied riders as the Numidians bore down on them, but the circumstances were different on this side of the battlefield. The field was open for maneuver, as Paullus feared when he first laid eyes on the terrain days earlier.

The Numidians harried their foes, advancing and turning away, a more traditional cavalry tactic. “From the peculiar nature of their mode of fighting, they neither inflicted nor received much harm, they yet rendered the enemy’s horse useless by keeping them occupied, and charging them first on one side and then on another,” wrote Polybius. The fighting between the two cavalry forces went inconclusively for a time, but the scales soon tipped against the Roman allied horsemen when the Numidians received reinforcements in the form of the Iberian and Gaulish riders led by Hasdrubal. Once finished with the Roman cavalry by the Aufidius River, Hasdrubal reformed his men and rode to the assistance of the Numidians, adding his numbers to theirs. Daunted by the overwhelming numbers, the Roman cavalry fled.

Hasdrubal then made a cunning and sage decision. He directed the Numidians to pursue the fleeing Roman allies. This prevented them from reforming and returning to the battle. Next, he regrouped his own troops and together they rode back to the battle, joining the Libyo-Phoenicians.

At that point, the Roman infantry was in serious trouble. It had been abandoned by its cavalry as Hasdrubal’s force rode into its rear. By this time, the Roman rear ranks were probably turned about to face the new threat since the Libyo-Phoenicians were so deep on their flanks. It is also likely the Roman velites light infantry were present in the Roman rear, since they would normally withdraw through the main lines to the rear after they skirmished. These lightly armed and armored fighters were ill equipped to face enemy cavalry. The Carthaginians launched rolling attacks all along the Roman rear line, encouraging the nearby Libyo-Phoenicians as much as they disordered the Romans.

Despite the cavalry attacks and Carthaginian infantry swarming around them, the Romans still held firm. Many of their leaders set the example, including Paullus. He suffered a wound from a sling stone early in the fighting, according to Roman historian Livy. Despite his injury, Paullus moved along the lines, giving encouragement and exhorting his men to stand firm whenever it seemed they might break. Eventually the consul grew too exhausted to remain on his steed and his retinue dismounted with him. The Carthaginians attacked them, angry that the Romans refused to surrender despite the growing odds against them. Paullus’s men were slowly cut down. A few of them climbed back on their horses and rode away, but Paullus was not among them. He stayed behind and fought on until a band of Carthaginians cut him down.

Servilius was also killed about the same time. The loss of both generals caused the Roman infantry to start breaking. Groups of men within the cauldron began trying to push through the surrounding Carthaginians and make their escape. Even this became ever more challenging as the Carthaginian infantry pushed inward. More and more Romans in the outer ranks were killed or wounded and had to be pulled back. Being behind the front ranks provided no safety, however. Sling stones and javelins from the light infantry rained into the Roman center while the spearman and swordsmen around the shrinking perimeter hacked and thrust into legionaries so tightly packed some could not use their own weapons.

This continued until the Romans lost all cohesion and became merely a panicked mob awaiting death from all around them. The outcome was guaranteed as the last men were cut down either in small groups or individually. The immense battle ended with a mass of dead and dying Romans on the field. A few thousand of their infantry managed to break free and escape. They ran off to nearby towns while 300 of the Roman cavalry also escaped. The victorious Carthaginians quickly moved on the Roman camp, killing 2,000 of the troops left to guard the encampment and taking the remainder prisoner.

The battle was a complete disaster for Rome. The Romans suffered 55,000 casualties compared to 5,700 Carthaginian casualties. Paullus, 80 senators, and 21 tribunes were among the Roman dead. Many of the lost equites were also men of standing or wealth. Varro fled with the remaining allied cavalrymen and survived. He rode with 70 other survivors to Venusia. Polybius would recall his conduct poorly in his later writing.

The battlefield was a horrifying scene, covered in the dead and dying. “So many thousands of Romans were lying, foot and horse promiscuously, according as accident had brought them together, either in the battle or in the flight,” wrote Livy. “Some, whom their wounds, pinched by the morning cold, had roused, as they were rising up, covered with blood, from the midst of the heaps of slain, were overpowered by the enemy. Some too they found lying alive with their thighs and hams cut, who, laying bare their necks and throats, bid them drain the blood that remained in them.”

Hannibal achieved a great victory at Cannae. His double envelopment, in which the forces of one army simultaneously attack both flanks of the enemy army in order to encircle it, became a textbook military maneuver emulated by modern commanders. Hannibal destroyed eight Roman legions and their matching allied legions. The defeat came as a terrible blow to Rome and did serious damage to its reputation.

Some of Hannibal’s generals suggested the army rest after achieving such an overwhelming success, but Maharbal disagreed. He suggested the entire Carthaginian army march on Rome immediately and finish the war. Maharbal even volunteered to ride ahead with his cavalry, believing he could get to the city before its citizens knew he was coming. While applauding Maharbal’s motivation and energy, Hannibal chose not to follow up with the immediate attack. “You know how to conquer, Hannibal, but you do not know how to make use of your victory,” responded Maharbal.

There was truth in Maharbal’s words. Hannibal possessed great tactical skill. He set the conditions for the Battle of Cannae and the Romans obliged, allowing Hannibal to dictate the course of the fighting. Over the course of the war Hannibal did this several times, taking advantage of the Romans’ aggressiveness and impatience. Rome’s martial traditions resided in a belief in the offensive, and Hannibal bled them dearly for their inflexibility.

In the wake of Hannibal’s string of victories, the Greek-speaking cities of southern Italy, Sicily, and Macedon renounced their alliance with Rome. But Rome’s other allies remained loyal. Hannibal eventually offered reasonable peace terms, but the Roman Senate rejected them.

Hannibal underestimated the Roman will to continue the fight. It did not occur to him that the Romans would refuse to yield and would never accept defeat. The stakes were simply too high. What is more, the sting of the routs the Roman army suffered brought calls for vengeance against the Carthaginians.

Over the course of a two-year period beginning in 214 bc, Rome ultimately captured the Greek city of Syracuse in Sicily. The achievement was the work of Marcus Claudius Marcellus who arrived with a fleet and an army. He had equipped some of his warships with siege engines and ladders to assault the strongly held city from the water.

The brilliant inventor Archimedes developed countermeasures that initially thwarted the Romans. One of these consisted of a hook that could reach out over the water and capsize Roman vessels. The Romans repulsed efforts by the Carthaginians to relieve the city. An elite group of Roman soldiers managed to infiltrate the city. The conquest spelled the end of the independence of the Greek cities in southern Italy and Sicily.

By 207 bcHannibal’s army in Rome had lost its ability to conduct offensives owing to shortages of men, money, and equipment. His brother, Hasdrubal, arrived from Iberia with badly needed reinforcements. Marcus Livius led a Roman army that blocked Hasdrubal’s march on the banks of the Metaurus River northeast of Rome. Livius’s second in command was the promising General Gaius Claudius Nero. The Iberian infantry drove back the Roman left wing and appeared close to victory when Claudius Nero conducted a stunning flank attack against the Carthaginian right wing. The Carthaginian cavalry fled the field, which allowed Claudius Nero to roll up the Carthaginian infantry without interference from enemy horsemen. Hasdrubal was among the slain.

The Romans achieved the pinnacle of revenge. A new Roman general named Scipio, who had survived the carnage at Cannae, invaded Iberia to deny it to Hannibal as a source of supply. He captured and sacked New Carthage. Scipio also inflicted a serious defeat on the Carthaginians at Ilipa in 206 bc. Two years later, he landed in Africa where he easily trounced the local forces. Fearing the fall of their great city to Scipio, the Carthaginians recalled Hannibal from Italy.

A grand battle unfolded on October 19, 202 bcon the plains of Zama southwest of Carthage. Hannibal sent his 80 war elephants against Scipio’s troops, but the Romans opened ranks to allow the elephants to pass through where a special force at the back of the army was entrusted with slaying them.

Scipio then hurled his cavalry at their Carthaginian counterparts. They did so in grand fashion, routing the Carthaginian horsemen. Although the Carthaginian infantry performed well in their attack against the Roman foot soldiers, Scipio’s cavalry attacked the Carthaginian rear. It was a decisive victory with 20,000 Carthaginian casualties and 26,000 prisoners. The Romans lost only 6,500 men. This marked the end of the war. Scipio imposed harsh terms on the defeated Carthaginians. For his great victory, Scipio received the honorific “Africanus.”

Hannibal went into exile, but the Romans pursued him wherever he went, demanding his extradition. The Romans trapped him in 183 bc. “Let us now put an end to the great anxiety of the Romans, who have thought it too lengthy and too heavy a task to wait for the death of a hated old man,” he said. With those words, the victor of Cannae and scourge of the Roman Republic took poison rather than suffer capture and humiliation at the hands of his foe.