By Bob Bergin

Thirty-five Boeing B-17C Flying Fortress bombers of the 7th Bomb Group happened to be on their way to Asia the morning the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. They had been sent to reinforce U.S. Army Air Corps units in the Philippines. Eight of the B-17s arrived at Hickam Field while the Japanese attack was in progress. Three were attacked by Japanese fighters and damaged; one was set afire, becoming the first American-flown B-17 destroyed in World War II. The encounter was one sided; the B-17s’ machine guns had been removed from the bombers to reduce their weight for the long flight over the Pacific. It was a dramatic introduction to World War II.

The 7th BG eventually regrouped in Australia; some of its elements were sent on to join in the futile Allied defense of Java. When Java fell, the group was ordered to India to fly against the Imperial Japanese Army, which had occupied Thailand, Malaya, and Burma. In June 1942, most U.S. heavy bombers based in India were sent to the Middle East to stop German General Erwin Rommel’s advance toward the Egyptian frontier. That reduced the 7th Bomb Group to a single squadron of B-17s and two squadrons of North American B-25 Mitchell medium bombers.

In August 1942, American war planners decided that the 7th would be reconstituted as a heavy bomb group with four squadrons. The new commander of the Tenth Air Force in India, Brig. Gen. Clayton Bissell, did not consider the B-17 suitable for the China-Burma-India Theater (CBI). The Flying Fortress lacked the range required by the long distances in the theater. He asked that the group’s B-17s be replaced by Consolidated B-24 Liberators. Given heavy demand in the European Theater for the Liberator, it would be months before the B-24s reached India. In the meantime, the group flew out of Calcutta and Agra while a new base was prepared for the 7th at Pandaveswar, India, outside Calcutta.

In 1942, the Allied position in the CBI was precarious. The British Army’s defense of its Burma colony collapsed quickly; surviving British forces retreated to India, which the Japanese were already preparing to conquer. America had just entered the war and was still mustering its forces and establishing the complex logistical network required to support sustained military operations.

The Japanese Army in Burma had its own logistical challenges. All of its military equipment and supplies had to come from Japan by sea, a voyage of 4,000 miles from the home islands to ports in Burma and Thailand. From those ports to the Burma front lines the journey included an additional 2,000 miles of single-track railroad line. Burma’s heavy jungle offered concealment for the Japanese and made them difficult to target and engage from the air. There were no industrial targets beyond the area of the Burmese capital at Rangoon, and thus an observer wrote, “The air war in Burma became a war against enemy communications and supplies.… The interruption of the movement and transshipment of supplies by sea or land into lower Burma became the primary objective of the 7th Bomb Group.”

The 7th BGs’ bombers first went after the major targets, the ports at Bangkok and Rangoon, and Japanese shipping heading there via the Gulf of Siam, the Andaman Sea, and the Bay of Bengal. In doing so, the 7th set bombing records. On December 19, 1943, the group flew the longest known mission of the war at that point, to Bangkok, a 14- to 15-hour flight. It also inaugurated new bombing techniques. On November 1, 1944, the campaign to destroy Japanese lines of communication in Burma began, and bridges became the primary targets.

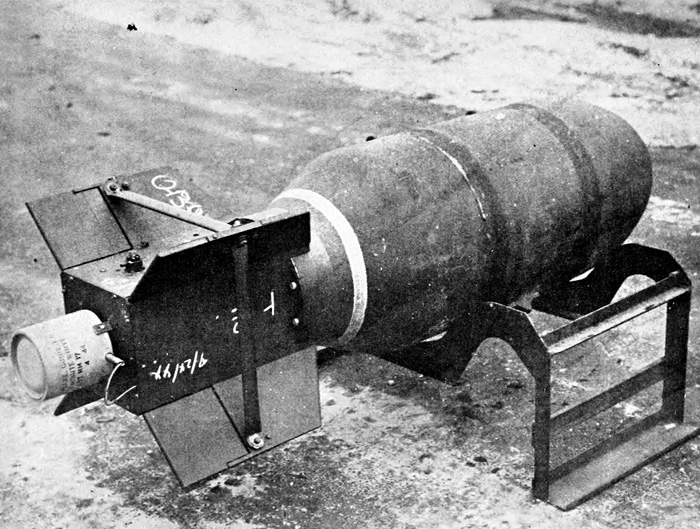

Author Edward M. Young, in his book B-24 Liberator Units of the CBI,notes, “Bridges were never easy targets. An analysis of the bombing effort during 1943 had shown that the 7th’s Liberators had managed to achieve only one direct hit for every 81 sorties, and these were targets that required direct hits—near misses did little damage to a bridge’s structure…. Part of the solution to the problem of bombing bridges came with the introduction of a new weapon, the AZON bomb.” This was the first American smart bomb, a 1,000-pounder with a radio-controlled tail fin that allowed the bombardier to maneuver the weapon after it had been dropped to correct deflection errors in flight. A flare attached to the rear of the bomb enabled the bombardier to track its fall.

The AZON designation derived from “azimuth only,” which meant the bomb could be steered left or right but lacked pitch control. Much like today’s Joint Direct Attack Munition (JDAM), the AZON control and guidance package was attached to the tail of a standard 1,000-pound bomb. The Eighth Air Force initially tried AZON bombing in Europe in the latter half of 1944, with disappointing results. Apparently Europe’s inclement weather, the rain and the fog, affected AZON guidance. But in the clear, dry weather of Southeast Asia’s hot season, AZON bombs proved ideal for attacking the narrow bridges on the Thai-Burma rail lines. By November 1944, the group had 10 dedicated AZON B-24s fitted with necessary transmitters and antennas and flown by crews specifically trained in the AZON technique. They were assigned to the 7th’s 493rd Bomb Squadron.

The group also developed a new bombing technique. Referred to in some histories as “dive bombing,” it actually was “glide bombing” when performed with a B-24. Young notes, “A form of glide-bombing with a sharp pull-up at the end of the glide could send a bomb directly into a bridge structure instead of it bouncing off as had happened in many low-level attacks…. The pilot would approach the target along its long axis, begin a 20 to 25 degree glide at 1,500 feet, and release the bomb at 500 feet as he pulled out. A toggle switch was fitted to the control column so that the pilot could release the bomb using a special sight designed specifically for that purpose.” On April 24, 1945, a total of 41 Liberators from all four of the 7th’s squadrons were sent out, the 493rd squadron equipped with AZON bombs, the other three prepared for glide bombing. Thirty bridges were destroyed, and 18 were damaged—a spectacular success.

B-24 bombardier Lieutenant Guilford W. “Chip” Forbes got into the fight at the tail end of the war. He arrived at the 7th’s base at Pandaveswar in January 1945. By that stage of the war, American and British fighter groups in India had established air superiority, but there could still be a lot of flak. Forbes recalled, “Flak could be very heavy, or very light. It depended where you went. On all the missions we flew, we never saw a Japanese fighter.”

All of the missions were long ones and not all targeted railroads. One of the longest of Forbes’ early missions was to the port of Bangkok, his target a drydock that was duly put out of commission. On March 19, 1945, he participated in a mission to the Kra Isthmus, the narrowest part of the Malay Peninsula. All four of the 7th’s squadrons were represented by the 37 B-24s that participated in the raid. The targets were railroad bridges on the Bangkok-Singapore rail line. Each aircraft carried only four bombs; two bomb bays were fitted with extra gas tanks to hold the fuel required by the long flight. Orders were to fly to the target at 400 feet, “a ridiculously low altitude for a B-24,” remembered Forbes. “We heard that the strategy for this raid came right from the top commander in the CBI, Lord Mountbatten, and we griped mightily about his misuse of B-24s.”

Forbes continued, “Lumbering along at 400 feet, a B-24 is an easy target.” Sure enough, Forbes’s B-24 was struck by small-arms ground fire that cut three fuel lines in the bomb bay. “With the bomb bay doors wide open and fuel spilling, our plane was a big-time atomizer,” he added. “We were afraid the next hit would make a spark and the plane would go off like a firecracker.” Forbes and the flight engineer tried to find the leak in the bays with the extra gas tanks as their clothes got saturated, and the pilot started thinking it might be necessary to ditch in the sea. Forbes’ fingers found the leak, finally, and the mission continued. Several significant bridges were among the targets destroyed. The flight was a round trip of 2,700 miles; it took 17½hours, the longest B-24 formation flight made in the CBI.

On March 22, Forbes’ crew went on a 10-plane raid to Great Coco Island, the north end of the Andaman Island chain, and this time bombed from 3,800 feet. Under normal procedures the Norden bombsight was linked to the autopilot, and course changes on the bomb run were made automatically. But the autopilot was not working; the pilot had to fly manually. Forbes’ primary targets were miniscule from their altitude, two small trailers, about six feet by 10, on which radar equipment was mounted. The targets were about a half mile apart, and each required a separate pass. Forbes had three bombs for three passes. “Everything worked perfectly; two passes, two bullseyes,” he remembered. For the third pass, Forbes picked a building related to the radars “and made another bullseye…. I really believe we could have hit a pickle barrel that day.”

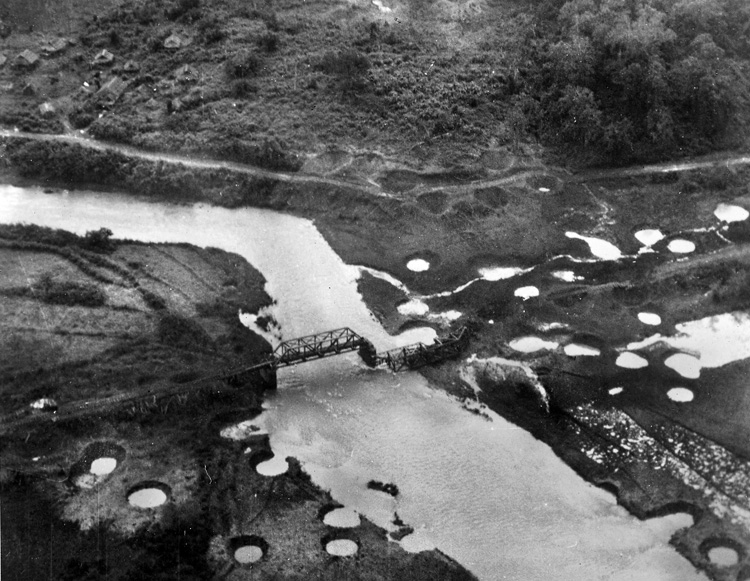

One of the 7th’s more difficult targets became famously known after the war as the “Bridge on the River Kwai.” More than 70 years later, there are still questions about the existence of that bridge and its fate. In the novel that became a popular film, a wooden bridge was built by British prisoners of war and destroyed by British commandos. The reality was somewhat different. There were, in fact, two bridges over a river called the Kwai Yai, both built by prisoners of war and both destroyed before the war ended—by American bombers.

About 325 feet north of a wooden bridge on the river was a second, more substantial looking structure of concrete and steel. Both bridges had been built in 1943 by the forced labor of Allied prisoners of war who were used by the Imperial Japanese Army to construct a railway linking Thailand to Burma. The railway that stretched from Bangkok to Rangoon was built under extreme conditions through hilly jungle terrain. The British government, which ruled Burma as a colony, had considered such a project as early as the late19th century but concluded that it was too difficult to carry out. The Japanese used about 200,000 Southeast Asian workers in the railway’s construction, many of them as forced labor, and about 60,000 Allied POWs. About 90,000 Asian workers died, and more than 12,000 Allied POWs perished. The wooden bridge was the first completed, in February 1943; the concrete and steel structure was completed several months later. By October 1943, when the railway was completed, the Japanese were able to move thousands of tons of supplies to their military forces in Burma every day.

At the end of November 1943, two B-24 missions were sent against the concrete and steel bridge on the River Kwai, which was designated “Bridge 277.” The bridge remained standing. On December 13, the group’s 9th Squadron attacked Bridge 277 again while the 436th Squadron bombed flak batteries guarding the bridge. When the smoke cleared, the bridge stood. It would be attacked so often that the [concrete and steel] structure would become known within the 7th as “Old 277.” Finally, on February 13, B-24s carried out an attack at 300 feet and dropped two of the spans of the concrete and steel bridge into the river. By early April, photoreconnaissance showed that although the steel bridge remained unusable, damage that had been done to the wooden bridge had been repaired and trains were again moving over it. The 7th now had the job of eliminating the wooden bridge. The story of how the wooden “Bridge on the River Kwai” was finally destroyed, as told by Chuck Linemen, the pilot who led that raid, gives a good sense of how 7th BG missions were conducted, and of the challenges the crews faced.

On the morning of April 3, 1945, a few minutes before 9 am, a lone aircraft appeared in the clear sky above Kanchanaburi, a small town in western Thailand. The plane was set on a course that would take it over a wooden bridge that spanned the river on the northwest edge of the town. The river at that point was known as the Kwai Yai, and, because of a fictional bridge in a novel that would be written years later, Kanchanaburi would become known as the site of the “Bridge on the River Kwai.”

The lone aircraft over Kanchanaburi on the morning of April 3 was a B-24 Liberator from the 436th Bomb Squadron of the 7th Bomb Group. In command of the aircraft was 20-year-old 1st Lt. Charles Linamen from Ashland, Virginia, known to his crew as “Curley.” The nine others who made up the crew included copilot Inyron Bradley Harnlett, navigator Raymond A. Henderson, engineer-gunner William A. Nations, radio operator-gunner Bernard K. Bondurant, armorer-gunner Clifford B. Webb, assistant armorer-gunner Herbert Clyde Saylor, nose gunner George Barrett Twelvetree, and tail gunner Raymond F. Hertzin.

The mission had started eight hours earlier with a briefing at the 7th BG’s airbase in India. The target of the mission was designated as “the bypass bridge at Kanchanaburi” to distinguish the functional wooden bridge from its heavily damaged concrete and steel neighbor. Linamen’s B-24 would lead the raid, and six other B-24s would follow one-by-one at 10-minute intervals. Linamen’s aircraft would make three bomb runs over the bridge and on each run drop two 1,000-pound bombs. Because of its importance, the bridge was well protected by Japanese antiaircraft guns. An attempt to neutralize these guns would be made by flak-suppression aircraft, B-24s that would sweep over the area just before Linamen arrived on target and drop antipersonnel bombs on the gun positions. Hopefully this would silence the guns before Linamen’s aircraft started its bombing run.

Takeoff was at 2 am. Linamen’s B-24 turned on a southeasterly course, over Calcutta, out over the Bay of Bengal, across the tip of Burma, and then due east to Thailand. The night was dark; there was no moon and few stars. No lights showed from the B-24 as it flew low to avoid detection by radar.

They had flown past the southern tip of Burma when the tail gunner became aware of another aircraft that flew alongside them, no more than 229 feet away. By its size and shape, it was a fighter. In this area—well beyond the limited range of Allied fighters—there was no question that it was Japanese.

The tail gunner alerted Linamen who instructed him to track the fighter carefully in his gunsight but not to open fire unless the fighter made an aggressive move toward the B-24. Ten tense minutes passed while the Japanese fighter and the B-24 flew side by side. Suddenly the fighter banked away and headed back toward Burma. In the darkness, the B-24 crew thought about what had happened. Because of the blackness of the night it is possible that the Japanese pilot never saw the B-24. If he did, he chose not to fight.

Linamen’s B-24 reached Kanchanaburi just before 9 am. The sky was empty. There was no sign of the flak-suppression aircraft that were to precede the bombing raid. Linamen did some calculations. The return flight to India was a long one, and fuel conservation was a major concern; it was not wise to wait. Linamen alerted the crew that they would go ahead with the bomb run. At 8:59, Linamen started the first run over the target at an altitude of 6,000 feet. He was conscious of the Japanese antiaircraft guns below and the Allied prisoner of war camp that was located near the western end of the bridge.

The Japanese gunners opened fire, and shells stared exploding above the aircraft and to its right. When the B-24 was directly over the bridge, bombardier Bill Henderson released the first two bombs. For an unknown reason only one bomb fell away from the aircraft. The crew watched it fall until it struck the bridge and exploded. A direct hit! One span of the wooden bridge was destroyed.

Linamen turned the B-24 left in a wide circle that lined the aircraft up with the bridge for a second time. The Japanese antiaircraft gunners adjusted their aim, and the shells started exploding closer to the B-24 now, but still high and to the right. The bombardier released two more bombs, and both fell away this time. They exploded in the river, close to the bridge but they did not hit it. Linamen again banked the B-24 into a left turn and started the third bombing run on the bridge.

The Japanese gunners made more corrections and now had the B-24 bracketed. The bombardier toggled all three of the remaining bombs. As they dropped away from the aircraft, Henderson asked Linamen to hold the B-24 steady so that a camera in the aircraft could record the damage done to the bridge. As the last three bombs exploded close to the bridge, Linamen kept the aircraft straight and level. He was ready to turn away from the target when Japanese shells struck the aircraft. The two rear bomb bay doors were blown away. Three feet of the right wing tip vanished, followed into oblivion by a section of the right vertical stabilizer. Linamen did not realize it immediately, but an important control cable had also been cut and the B-24’s ailerons were now useless. The B-24 started a steep diving turn to the right.

The pilot had his hands full. As the aircraft headed down, it seemed to Linamen that the right outboard engine had probably been shot out. He applied left rudder and left aileron and pulled back on the control wheel to get the aircraft out of its dive. He called for the copilot to increase power. Slowly, the B-24 came out of its dive, but despite Linamen’s best efforts he could not get the wings level. When he glanced at the engine tachometers he saw that all four engines were reading normally. It was not an engine causing the problem.

Linamen twisted the yoke on the control column left and right to activate the ailerons. Nothing happened. He felt his stomach drop. There was no aileron control and—according to the men who had designed and engineered the aircraft—the B-24 was not supposed to be able to fly without ailerons!

Linamen hit the alarm bell to alert the crew to a possible bailout. The crew prepared to abandon the aircraft, but Linamen did not want anyone to bail out until it was absolutely imperative. They were over enemy territory and 1,500 miles from the nearest Allied base. They were not far from the target they had just bombed. The longer they stayed in the air, the closer they would get to friendly territory.

Things were not looking good, but Linamen did have something to think about. In the diving turn that occurred when the aircraft was first hit, it had lost 4,000 feet of altitude and the airspeed had increased to 170 miles per hour. When Linamen instinctively stomped down on the left rudder to stop the turn, the right wing rolled level. Linamen had accidentally learned how he might be able to control the plane—with one hitch. When the aircraft’s speed dropped below 160 miles per hour, the right wing dropped and the aircraft turned right and started to dive. When that happened, Linamen would have to build up airspeed to regain rudder control and then use the left rudder to lift the damaged right wing.

The B-24 flew on at an altitude of 2,000 feet. To clear the mountains en route to its base, the aircraft needed at least 4,000 feet. Linamen began a tedious climb to higher altitude, keeping speed higher than normal and using higher than normal power settings. This meant that the B-24 was burning more fuel than normal. Linamen thought about the condition of the aircraft. He did not know how badly it was damaged or how long it would stay together. It did not seem likely that the aircraft could reach India. Linamen reviewed the options. One possibility was to head south for the Andaman Islands where supplies were stored for just such emergencies.

To avoid the areas with the heaviest concentrations of Japanese, Linamen turned due west toward the Bay of Bengal. When they finally reached water, Linamen decided to try to reach “Cox’s Bazaar,” a British airfield outside Akyab, Burma. Linamen knew the airfield; he had landed there in the past. The B-24 turned to follow a northwestern course along the Burma coast. Cox’s Bazaar was seven and a half hours away, but Linamen had coaxed the B-24 up to 6,000 feet.

With Cox’s Bazaar in sight, Linamen alerted the crew. He told them they had the option of parachuting; he was not sure he would be able to maintain control of the aircraft when he tried to land it. One of the gunners asked what Linamen would do. “Ride it down,” he said. “What the hell are we waiting for?” was the response from the crew.

Airspeed on the approach had to be kept above 160 miles per hour to keep the wings level and the aircraft in a straight line. To add to the problems, there were many B-24s lined up wingtip to wingtip on both sides of the runway. Landing a crippled aircraft on the runway would be a great risk. Loss of control could send the cripple plowing through the rows of parked B-24s. Linamen decided to abort the approach to the runway and try to land instead on the beach at the edge of the airbase.

Linamen flew north of the base then turned south and started to let down. Indicated airspeed was kept at 170 to 175 miles per hour to keep the wings level. As they flew over a small inlet, crewmembers took their crash-landing positions. As they neared the ground everything seemed to be going well. When Linamen leveled the B-24 off to set it down, speed dropped to 155 miles per hour, and a crosswind started to drift the B-24 left toward the sand dunes. Linamen touched right rudder. This spoiled the airflow over the wing and caused the aircraft to lose its lift. It stalled and hit the ground at 155 miles per hour. Linamen flipped switches off as the aircraft hurtled over an area where backwater was held in a shallow hollow about 196 feet across. The nose gear snapped off. With its nose now plowing through the pool of water, the B-24 came to an abrupt halt. Exit hatches were flung open, and all 10 crewmen got out of the aircraft as quickly as they could. The B-24 was a write-off. It had been a brand new plane.

The wooden “bypass bridge at Kanchanaburi” was not rebuilt after this mission. For bringing back the severely damaged B-24 and its crew, Linamen was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross.

The achievements of the 7th Bomb Group are summarized by James Young: “In nearly three years of combat the B-24s of the 7th BG dropped 13,165 tons of bombs in the course of nearly 500 combat missions and carried close to 3,000,000 gallons of fuel to China. The group lost 71 aeroplanes, 48 on combat missions and 23 on ‘gas hauling’ missions.”

An interesting sidelight has emerged. During Southeast Asia’s monsoon season, from about mid-June to the end of September 1944, when extreme weather interfered with aircraft operations, the 7th’s B-24s were relieved from bombing missions and sent to haul gasoline to China over the famous “Hump,” the Himalayas. To convert the aircraft to tankers, gun turrets were removed and three gunners left behind; three 420-gallon tanks were installed in the bomb bays.

Flying the Hump involved some of the most dangerous missions of the war. They were flown through heavy rain, ice, and extreme turbulence. Foul weather took its toll, but so did overloading. The conditions were reflected in aircraft losses. The 7th Bomb Group lost more B-24s flying the Hump than in combat that year.