By Robert L. Durham

At the Battle of Jonsborough, Union General William T. Sherman hoped to destroy the Army of Tennessee and seize Atlanta, Georgia. By late August 1864,the situation of the Confederate Army of Tennessee in Atlanta had become extremely grim. Its new commander, General John Bell Hood, had counterattacked the superior forces of red-bearded Maj. Gen. William T. “Cump” Sherman’s forces in their positions north, east, and west of Atlanta with no success. Each loss added to the list of Confederate casualties that numbered in the thousands. Sherman had devised an effective plan of cutting the railroads into Atlanta, and the last order of business was to sever the Macon & Western Railroad.

While Hood pondered his remaining options, “Cump” ordered the vanguard of his army to pack 15 days of rations and begin marching south around the western rim of Atlanta to Jonesborough, Georgia, which was situated on the railroad that entered the city from the south. Sherman entrusted one-armed Maj. Gen. Oliver O. Howard with overseeing the movement. By the evening of August 27, all of Sherman’s army, except the XX Corps, was between Sandtown and Atlanta. Hood learned about the Union movements from his cavalry; however, he was in the dark as to exactly where Sherman planned to strike.

For four long months Union and Confederate forces in northern Georgia had ground away at each other, leaving the landscape on the Chattanooga-Atlanta corridor dotted with the graves of fallen Johnny Rebs and Billy Yanks. Sherman, who had replaced General Ulysses S. Grant on March 18, 1864, as the commander of the Military Division of the Mississippi, had departed Chattanooga and crossed into Georgia in May 1864 with his three Union armies. He fought his way steadily south over the roughly 100 miles to the Athens of the South by repeatedly outflanking Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston’s smaller Army of Tennesee. Facing the superior Union numbers, Johnston took up one strong position after another only to see it turned by the resourceful Sherman. By early July, Johnston’s back was against the Chattahoochee River just north of Atlanta.

Sherman was acutely aware that U.S. President Abraham Lincoln needed a decisive Union victory to increase his chances for reelection in November. As commander of the Military Division of the Mississippi, Sherman had 100,000 men under his command. Although Sherman had substantially more men than Johnston had in the Confederate Army of Tennessee, the Confederates had strong fortifications surrounding Atlanta. A headlong attack against those fortifications was sure to be bloody, and it was by no means certain of victory.

The Confederates had their own problems. Confederate President Jefferson Davis wanted an aggressive commander who would put up a more effective defense against the Union Army at the gates of Atlanta. Dissatisfied with Johnston’s tactics, Davis sacked him on July 17. Davis replaced Johnston with Hood, who was promoted to full general.

Hood counterattacked on July 20 at Peachtree Creek north of the city but suffered a bloody repulse. Unfazed, Hood attacked again on July 22 in what became known as the Battle of Atlanta. This time the Confederate commander sent Lt. Gen. William J. Hardee’s corps on a 12-mile forced march to get around the Union left flank east of the city. But Hood miscalculated the time it would take for Hardee’s corps to get into position. Union Maj. Gen. James McPherson committed reserve forces to hold his position. Although the Confederates broke through his line briefly, they were driven back by heavy artillery fire. Hood lost 7,000 men he could ill afford to lose, while the Union Army lost McPherson, who was killed in the confused fighting when he inadvertently rode into a group of Rebels from Maj. Gen. Patrick R. Cleburne’s hard-hitting division. Sherman gave command of McPherson’s troops to Howard, who had been transferred to the western theater from the Army of the Potomac.

Sherman’s plan was not to attack Atlanta headlong but to send Union forces to slip around the Confederate flanks and sever the rail lines that were the city’s lifelines to the rest of the South. Sherman eventually found that he could not effectively cut off Atlanta from the east without getting too far away from the railroad that supplied his army. For that reason, he ordered Howard to pull back and swing to the right in order to threaten the city from the west. The Macon & Western Railroad was the only open railroad supplying the beleaguered Confederate army in Atlanta.

Hood once again saw a chance to catch the Federals off balance. On July 28, he sent Lt. Gen. Alexander Stewart and Lt. Gen. Stephen D. Lee to launch a coordinated attack against Howard. Hood expected to catch Howard on the move, but Howard had already entrenched by the time the Rebels attacked. The battle unfolded in the woods surrounding a rural chapel called Ezra Church. The botched attack cost Hood another 5,000 men. The Confederate Army was hemorrhaging badly. Hood had fought three large battles in nine days and come up short each time. The initiative reverted back to Sherman.

While Howard had shifted west of the city, Maj. Gen. George Thomas, commander of the Army of the Cumberland, and Maj. Gen. John Schofield, commander of the Army of the Ohio, had maintained a steady bombardment of Hood’s forces opposite them. On August 26 all of the Union forces except for Maj. Gen. Henry Slocum’s XX Corps of the Army of the Cumberland had vanished from the trenches opposite Atlanta. Sherman had put in motion the Union operation to cut the Macon & Western Railroad.

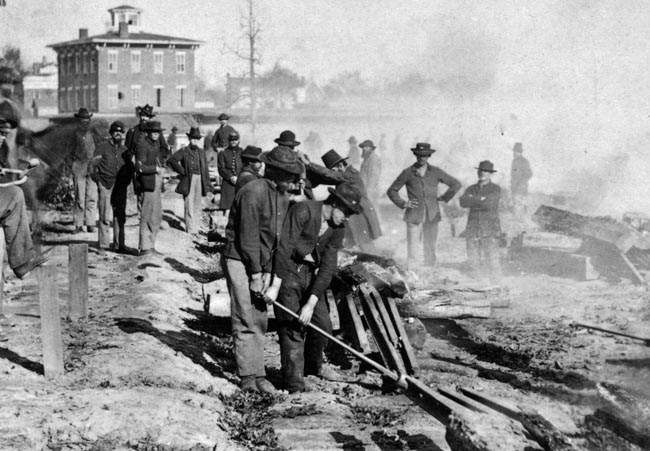

The Atlantic & Western Railroad joined the Macon & Western Railroad at Eastpoint a few miles south of Atlanta. As the Yankees marched around Atlanta, some of the units halted midway through their march to tear up sections of the Atlantic & Western Railroad before proceeding to the Macon & Western Railroad.

“In one and one-quarter hours we utterly destroyed rails and ties for twice the length of our regiment,” wrote Sergeant Charles Wills of the 8th Illinois Infantry, XX Corps, Army of the Cumberland. “We, by main strength with our hands, turned the track upside down, pried the ties off, stacked them, piled the rails across and fired the piles. Used no tools whatever.”

Howard’s troops in the vanguard arrived August 30 west of Jonesborough. Instead of occupying Jonesborough, which was lightly defended, they began entrenching on the east bank of the Flint River. On the east side of the river were bluffs that ranged from 100 to 200 feet in height. It was a strong defensive situation; to make it even stronger, Howard rested both flanks on the river. His battle line was more than a mile long. The Flint River paralleled the Macon & Western Railroad and in some places was only one mile from the railroad.

Part of the XV Corps, under Maj. Gen. John A. “Black Jack” Logan, arrived later than the others and needed to entrench hastily. The 55th Illinois, a regiment in the XV Corps, had to drive away some enemy sharpshooters and skirmishers before it could reach a prominent hill that provided a good position. “While half the brigade pushed back the enemy and held them in check, the rest piled rails and logs … into a rude low breastwork,” wrote Logan. “Lying behind this, with bayonets and tin plates—anything that could serve as a tool—the men dug into the hard gravel to increase their protection.” The Yankees built a second line of entrenchments behind the river, backed with artillery.

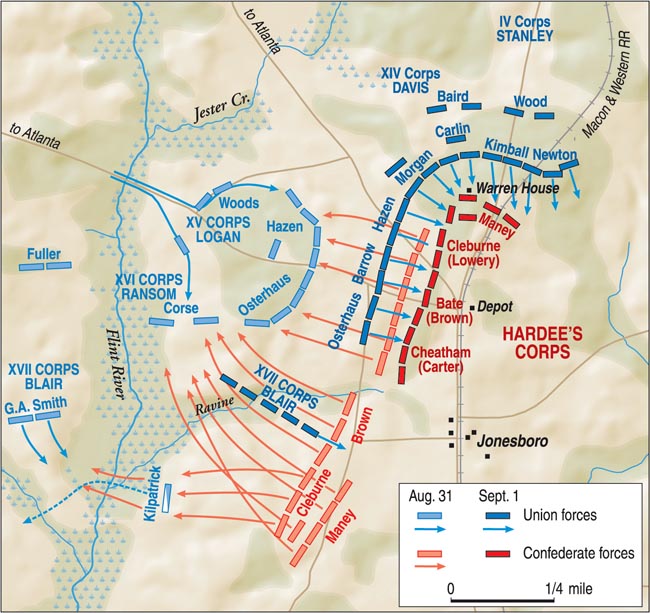

The Federal cavalry, under Brig. Gen. Judson Kilpatrick, picketed the Union right flank. The rest of the Army of the Tennessee was positioned, right to left: Brig. Gen. Thomas E.G. Ransom’s XVI Corps, Logan’s XV Corps, and Maj. Gen. Francis P. Blair, Jr.’s XVII Corps.

Hood knew that a large Federal force was threatening to cut his supply line with Macon, Georgia. He believed it was only two corps, though. He did not know that the force consisted of most of Sherman’s troops. On the evening of August 30, Hood ordered Hardee to take his own corps, which was commanded by Cleburne, and Lt. Gen. Stephen Dill Lee’s corps to Jonesborough. The Confederates expected to arrive before sunrise, but Cleburne’s corps, which was in the lead, encountered Yankees holding a bridge that they had to cross. Once a ford was found, Cleburne sent a communication for the rest of Hardee’s command to follow him.

“The darkness of the night, the dense woods through which we frequently marched, without roads, the want of shoes by many, and the lack of recent exercise by all [due to being in the trenches for so long,] contributed to induce a degree of straggling which I do not remember to have seen exceeded in any former march of the kind,” wrote Confederate Maj. Gen. Patton Anderson.

The head of the column did not reach Jonesborough until mid-morning on August 31. The lead brigade of Lee’s column did not get there until 11 am, and it was not until 1:30 pm that the entire command was in place. As the Confederates arrived, they immediately began fortifying their line.

Hardee’s corps deployed facing northwest. Cleburne’s own division, under Brig. Gen. Mark P. Lowrey, moved into position on the left. Brig. Gen. Hiram B. Granbury’s Texas Brigade of Cleburne’s division took up a position on the extreme Confederate left flank. The rest of Cleburne’s division consisted of Lowrey’s Alabama/Mississippi Brigade behind Granbury. To the right of Granbury were Brig. Gen. Hugh Mercer’s Georgia Brigade and Brig. Gen. Daniel C. Govan’s Arkansas Brigade. The other divisions of Hardee’s corps were Maj. Gen. W.B. Bate’s division, on the right of Cleburne, and Maj. Gen. Benjamin F. Cheatham’s division, in reserve behind Bate.

Lee’s corps deployed facing west to the right of Cleburne’s troops. Maj. Gen. Carter L. Stevenson’s division held the left, while Anderson’s division held the right. Maj. Gen. Henry D. Clayton’s division backed Anderson. The rest of Stevenson’s division was held in reserve behind the main line.

Hood told Hardee that the fate of Atlanta rested on his ability to push the Federals back across the Flint River at Jonesborough. He instructed Hardee that the Confederates should attack with fixed bayonets. Hardee planned to attack in echelon, from left to right, led off by Granbury’s brigade. An echelon attack was intended to compel the enemy to commit his forces against each seperate advance, thus leaving an easier path for the next advance in line.

Granbury began the attack as ordered. Granbury’s men were met by Kilpatrick’s dismounted troopers, with four cannons, behind rail breastworks. After a brief fight, Kilpatrick retreated across the Flint River.

Kilpatrick’s cavalry “just fairly made it rain bullets as long as they had any in their guns, but as soon as they gave out, and we were getting closer to them every moment, they couldn’t stand it but broke and ran like good fellows,” recalled Captain Samuel T. Foster of Granbury’s brigade. Contrary to specific orders, Granbury chased after them, beyond the river. The cavalrymen “outran us by odds,” Foster said.

Lowrey’s and Mercer’s brigades followed Granbury’s example, and all three brigades crossed the river. Lowrey commanded the three brigades to retire back across the river and to change the direction of their advance to the north, hoping to hit the Federal infantry in the right flank. Instead of finding the Yankees with their flank in the air, they discovered that their right was anchored on the river.

The three right brigades of Cleburne’s division, followed by Bate’s and Cheatham’s divisions, respectively, went up against the main Federal line. “Our men were true in emergencies…. On the command, ‘forward,’ they moved as one man with steady steps,” recalled Sergeant Sumner A. Cunningham of the 41st Tennessee. “Very soon we were in one of the fiercest battles of the war.” Before reaching the Yankee line, they were ordered to retreat. The men reformed and were ordered to charge again, but this met the same fate as the first charge.

“Soon our men begin to fall, rapidly and steadily we advance,” wrote Sgt. Maj. Johnny Green of the 9th Kentucky. “Just as we have fired the volley at them and begin to rush on them we come to a deep gully ten feet wide and fully as deep. No one can jump this gully and at this close range it will be impossible to clamber up the other side of the gully and reform to rush on them with fixed bayonets. The shot and shell and Minié ball [were] decimating our ranks.”

Lee, on the right of Cleburne, heard skirmish fire coming from the main line. He thought the chief attack had begun and hurled his men forward too soon. In addition to attacking ahead of schedule, their assault was confused. They attacked in two lines and Lee instructed the second line not to allow an interval of more than 100 yards between them and the line in front. Some of the lead brigades were slow in starting, which made it hard for the support brigades to keep the proper intervals and to keep an even alignment with each other.

“In front of the breastworks, a dense growth of timber and brushwood had been felled,” wrote Brig. Gen. Arthur M. Manigault. “This obstruction proved a serious inconvenience to our men, creating much irregularity in the line.”

Anderson led the right three brigades of Lee’s advance line. “They advanced up the ascent to within a pistol shot of the enemy’s works,” wrote Anderson. “At this point, under a deadly fire, a few wavered [and] the rest laid down. The line was unbroken, and, although the position was a trying one, every inch of ground gained was resolutely maintained…. Both men and officers in the front line were suffering severely. Each moment brought death and wounds into their ranks.”

The line officers shouted encouragement to the men under their command, urging them to stand firm. “Slowly but resolutely they advanced up the ascent to within pistol-shot of the enemy’s works,” wrote Anderson. “Every effort was made to hold the ground already gained. Stragglers were pushed up to the front and the slightly wounded were encouraged to remain there.”

The men of Colonel Theodore Jones’s brigade of Brig. Gen. William B. Hazen’s division of the Union XV Corps manned the left of their line opposite Anderson’s Rebels. “The first rebel line rushed into sight out of the skirts of the brush that fringed the slope, and when within a hundred paces our first volley met them full in the face,” wrote a soldier of the 55th Illinois. “A few of the more desperate reached the rifle-pits, but the main body was swept back to the shelter of the copse, leaving the hill crest covered with a bloody burden.”

The Federals of Logan’s corps encountered Lee’s men. “They came with a yell, attacking our whole line,” wrote Private John K. Duke of the 53rd Ohio. “We reserved our fire until they were quite close, when we opened up a continuous fire, some of our officers standing back of the firing line biting off the ends of cartridges and urging coolness and rapid fire…. The space between our works was strewn with their dead and wounded.”

Lee was repulsed all along the line. He informed Hardee that he did not think he could capture the Union position in a second assault. Hardee had received information, which later proved to be false, that the Federals were going to assault Lee. Therefore, he ordered Cleburne’s division to the right to reinforce Lee and went on the defensive. Night ended the fighting, and the Confederates withdrew behind the protection of the Jonesborough defensive works.

Although the Confederate attacks were fierce, the Federals repulsed them with relative ease. The casualties reflect the inequality of the contest. Confederates suffered 1,700 casualties, while the Union suffered only 200.

“The enemy attacked us in three distinct points, and were each time handsomely repulsed,” Howard informed Sherman. “Besides losing a host of men in this campaign, the Rebel Army has lost a large measure of vim, which counts a good deal in soldiering,” wrote Wills.

“The agonies of the wounded and dying, as they lay between the lines that night, was peculiarly horrible,” recalled Sergeant Cunningham of the 41st Tennesee.

The Confederate losses were not large enough to satisfy Hood. The attack “must have been rather feeble, as the loss incurred was … a small number in comparison to the forces engaged,” wrote Hood. Hardee’s failure to drive the Federals into the Flint River “necessitated the evacuation of Atlanta,” he wrote.

On the night of August 31, Hood ordered Hardee to return S.D. Lee’s corps to Atlanta. Hardee directed them to vacate their positions at 2 am. Cleburne’s division then spread out to occupy Lee’s position. Cleburne’s men were so few they had to fill the trenches in a single line. There was some delay, and Lee’s men did not get on the route back to Atlanta until daybreak.

The next morning the troops of Stanley’s IV Corps moved south along the Macon & Western Railroad. “Marching early, our brigade soon struck the railroad, and turning south, began the work of demolition,” recalled Sergeant Lewis W. Day of the 101st Ohio Infantry. “Everything that could be burned was committed to the flames; cedar ties proved to be excellent material for heating the rails, and adjacent trees offered solid supports for bending them; a roaring fire of cedar rails soon destroyed the wooden culverts, and a few pounds of powder blew up the stone ones. The railroad was utterly wrecked—nothing was left, except the roadbed, and even that looked exceedingly disconsolate.”

When they reached the existing Federal entrenchments, they formed on the left of Brig. Gen. Jefferson C. Davis’s XIV Corps, facing south against the right flank of Cleburne’s Confederate division. The rest of the XIV Corps faced southeast opposite the rest of Cleburne’s division. Logan’s XV Corps held the right of the Union line, facing east and confronting Bate’s and Cheatham’s divisions.

The Confederate entrenchments formed a fish hook, with the barbed end on the north, bending back to the right. The right flank faced north, and the center and left flanks faced west. Cleburne’s troops were in a single rank spaced a yard apart in order to fill their entrenchments. They were on the right, facing north, with Govan’s Arkansans holding the angle where the fishhook was curved.

To the left of Cleburne’s division were the men of Bate’s division and to the left of Bate’s division was Cheatham’s division. All of Bate’s and Cheatham’s troops faced west.

Because he believed Govan’s line was in a bad position, Hardee ordered its commander to move his line back and prepare new works. As his men carried out these instructions, they were also able to destroy the entrenchments they abandoned to deny their use to the enemy. But owing to the heavy fire from Union guns, Govan’ men were unable to destroy their old fortifications.

Hardee shifted Brig. Gen. “States Rights” Gist’s brigade at 1 pm from the extreme left of the line to the extreme right. They were formed with their left resting on the Macon & Western Railroad cut. The men received orders to strengthen their position as much as possible since they were responsible for holding the right flank.

“The men climbed up the small trees, bent them over, and, using pocket-knives to cut across the trunks, succeeded in a half hour in making a first-rate abatis of little trees, interlaced thickly, and held by half their thickness to the stumps,” wrote Colonel Ellison Capers of the 24th South Carolina. For breastworks, the men used rails and logs.

In the Union Army, Brig. Gen. James D. Morgan’s Second Division of the Union XIV Corps acted as a pivot for the right of the corps. They swung around until they were facing east and aligned, in a north-south direction, opposite the Confederate entrenchments. Left of them, the Federal line faced south to the Confederate right flank. Confederate guns opened on them as they crossed the Flint River.

The Third Brigade of the Second Division held the right of the line, the Second Brigade held the left, and the First Brigade was in reserve as they approached the Rebel entrenchments. On the left, they could see Brig. Gen. William P. Carlin’s First Division of the XIV Corps and Maj. Gen. David S. Stanley’s IV Corps.

“As far as we could see brigades were massed for a charge, with batteries thundering from the intervals between them, flags waving and flashing in the sunlight, staff officers dashing here and there, all made a martial scene grand and inspiring in the highest degree,” wrote First Sergeant Henry J. Aten of the 85th Illinois. “At the command the men moved forward with bayonets fixed and their empty guns at the right shoulder-shift.” The 17th New York Zouaves suffered heavily; their red turbans made them an inviting target.

The Federal columns began pushing their way through thick, swampy woods toward the enemy works at 4 pm. They were on a collision course with the Confederate field works that ran along a wooded ridge in the distance. Despite their fortitude, the Yankees had difficulty keeping their direction and alignment as they moved through swamps, ditches, and tangles of thickets. After an hour of slow but steady progress, the Federal units halted at 5 pm to dress ranks. They then surged forward along their entire front. Behind the main body, Brig. Gen. Thomas J. Wood’s Division of the Army of the Cumberland’s IV Corps, which constituted the Union reserve, moved south along the Macon & Western Railroad in columns to the left of the railroad.

Men on both sides watched tensely as the skirmishers became engaged and the roar of artillery grew in intensity. “Dirt, rock, slivers of rail and bushes, together with the grape and canister, as well as the Minié balls, filled the air with the most deafening noise,” wrote alf Hunter, adjutant of the 82nd Indiana.

Federal artillery fire pummeled Govan’s brigade. The Rebels endured frontal fire, crossfire, and enfilading fire. The brigade’s eight cannons were disabled, having had their wheels shot away. When the Union guns ceased fire, the men of Brig. Gen. Passmore Carlin’s First Division of the XIV Corps swept forward against Govan’s entrenched men.

“The entire brigade had to pass a morass, densely covered with brambles and undergrowth, so that it was impossible to preserve an exact alignment. The officers and men, however, pressed through the swamp, and rushed gallantly up the hill in the face of a galling fire from the enemy,” wrote Major John R. Edie of the 15th Infantry of the U.S. Regular Brigade.

Advancing on the left of the U.S. Regulars was Colonel Marshall F. Moore’s Third Brigade. “[We] threw out skirmishers, and moved forward through a dense thicket,” wrote Captain Lewis E. Hicks of the 69th Ohio. “We advanced to charge the rebel works. We reached a point within 50 yards of the works, and held it for 15 minutes, under a murderous fire, which speedily decimated our ranks.” The regiment’s colors were left in the no-man’s land between opposing lines when the color bearer was killed; however, the Yankees recovered them in their second charge.

“We assaulted the enemy’s intrenched position in the edge of woods, moving in line of battle through an open, difficult swamp, across an open field, under the severest artillery and musketry fire, flank and front,” added Captain Lyman M. Kellogg of the 18th U.S. Infantry of the U.S. Regular Brigade.

When his men stalled under the enemy’s galling fire, Kellogg sought to lead them through the hailstorm of lead by example. “I rode in front of my colors, and caused them to be successfully planted on the enemy’s works, jumping my horse over them at the time they were filled with the enemy, being the first man of our army over the enemy’s works.” The irate Rebels knocked Kellogg off his horse. While inside the enemy’s lines, he suffered severe wounds from shot and shell.

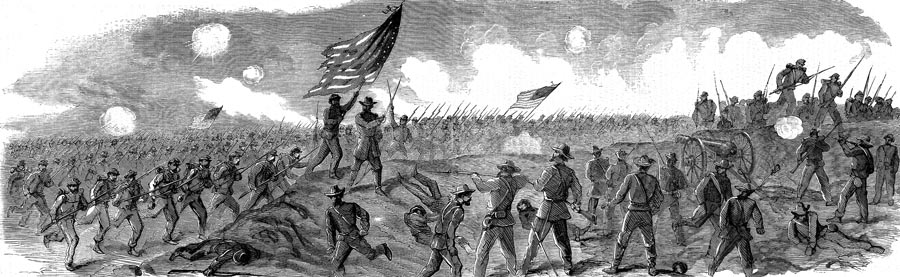

Govan’s Arkansas Rebels repulsed the first assault, but the enemy came again, in three columns, all converging on the Arkansans. They broke through the center of their line, capturing Govan, his adjutant general, 600 men, and the immobilized cannons.

“Although the odds were very great, the men gallantly contested their advance, fighting the enemy with clubbed guns and at the point of the bayonet, and thus a great many lost the opportunity for escaping,” recalled Colonel Peter V. Green of the 5th-13th Arkansas Consolidated Regiment. “The advance of the enemy was so rapid, and the woods on the right being so dense as to screen their movements, it was impossible to form any combinations to resist it.”

Granbury’s Texans were on the left of Govan. When the Arkansans’ line was broken the Kentucky Orphan Brigade’s right flank became exposed. “Our brigade [was] taken out of the works at a double quick and formed a line in rear of our works perpendicular to them facing the Yanks,” wrote Green. “Our battery [was] taken out of its position and wheeled around so as to face the new direction.” The Rebels waited patiently while the Yankees escorted their prisoners to the rear before resuming fire.

Vaughan’s Tennessee Brigade, in Cheatham’s division, arrived at this opportune moment, from the left of Hardee’s line, and was ordered to retake Govan’s old position. “Major-General Cleburne threw Vaughan’s brigade into the lurch, which, with the assistance of the remaining portions of Govan’s and Lewis’ brigades, completely checked the advance of the enemy,” wrote Brig. Gen. Mark P. Lowrey. Three of the regiments advanced too far to the left, coming up behind Granbury’s Texans, but the remaining regiment forced the Yankees in Govan’s entrenchments to assume the defensive.

“It was about five o’clock when the first [Union] line made its appearance, then another and another, until five double lines were in full view, coming in double-quick,” wrote George D. Van Horn of Swett’s battery of the Mississippi Artillery. “Our guns opened on them at a distance of three-quarters of a mile, and kept it up, the Yankees halting only at times to reline, then on again. Shortly our infantry commenced on them, and we began to use double charges of canister, but they kept coming.”

The Yankees surged over the Confederate breastworks in a desperate effort to silence the menacing guns. “Our infantry and artillery were still firing as rapidly as possible, but hundreds of them were climbing over the works,” continued Van Horn. “The first ones that came in found the gun already loaded and ready to fire. The embrasure was filled with howling Yanks.”

The Yankees swore and yelled at the Rebels in an effort get them to surrender or abandon their guns, but the resolute cannoneers stood fast. “One of them called to the man who was firing the gun that if he fired again he would run his bayonet through him, but the gunner paid no attention and fired, clearing out the porthole,” recalled Van Horn. “The Yank pulled down his gun and drove his bayonet through the gunner’s breast, pinning him to the ground, and, putting his foot on the man’s breast, jerked the bayonet out, leaving his man on the ground, as he thought, dead.”

One of the Yankee regiments that attacked Govan’s position was the 14th Ohio of Colonel George P. Este’s brigade. “After one of the most desperate hand-to-hand contests ever witnessed between two contending foes, the works were finally carried,” wrote Union Lt. Col. John A. Chase of the 182nd Ohio.

The 105th Ohio of Colonel Newell Gleason’s brigade supported Este’s men as they advanced against Govan’s brigade and Lewis’s Orphan Brigade of Kentuckians. “Este’s men dashed off with a wild cheer, carrying everything before them,” wrote Lieutenant Albion Tourgee of the 105th Ohio. The troops had fixed bayonets “along the whole front of the brigade,” Tourgee said.

The soldiers fired at each other at point-blank range. “I rose from a stooping posture in the trenches to shoot but just as I looked over our trenches a Yankee with the muzzle of his gun not six inches from my face shot me in the face and neck but fortunately it was only a flesh wound,” recalled Green of the 9th Kentucky. “It stung my face about as a bee sting feels but in my knees I felt it so that it knocked me to a sitting posture. But my gun was loaded and the other fellow had had his shot. I rose and put my gun against his side and shot a hole through him big enough to have run my fist through.”

At one point, a Union soldier poked his rifle through a small crack in the Rebel fortification and fired, killing two soldiers with one shot. Two of the Kentuckians grabbed the muzzle of his gun and bent it so that it could not be extracted.

The Union troops who overran Govan’s Arkansans swung around behind the Kentuckians. Many of the Confederates were captured, but the rest of the brigade fell back and then reformed.

Sherman had arrived at Jonesborough just before the Union attack began and was with Logan’s XV Corps. He was deeply pleased with the progress of the battle. “They’re rolling them up like a sheet of paper,” he said with evident delight.

Brigadier General William Grose’s Third Brigade of the IV Corps attacked the right flank of the Confederate line. “[They] pressed forward under a heavy canister fire from the enemy’s guns to within 300 yards of the enemy’s barricaded lines,” wrote Grose.

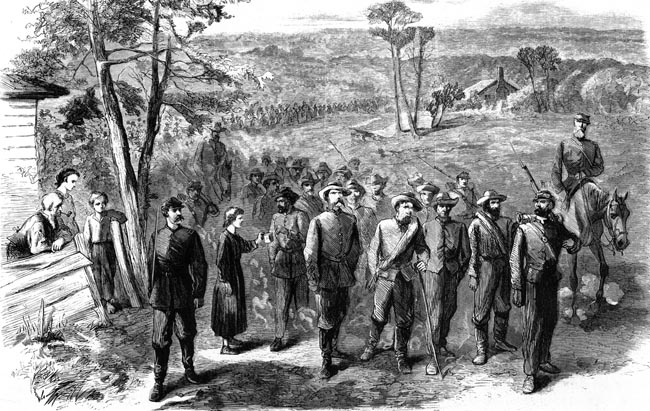

Brigadier General John Newton’s division of the IV Corps pushed forward around the enemy’s right flank, confronting only the Rebel skirmishers. They did not have much to do, but did capture a Confederate hospital, with the sick and wounded, about a dozen nurses, and a doctor. As the doctor was being led back through the lines, he said, “Billy Fed, we are sold; we did not expect such an army here.”

Both sides, blue and gray, were fought out. The majority of the Confederates had been pushed out of their original entrenchments but still held on. Hardee issued orders at 11 pm for his troops to withdraw from their positions. Despite the determined attacks of the Yankees, Hardee had held his position long enough to give Hood the amount of time he needed to evacuate Atlanta.

The Battle of Jonesborough “decided the fate of Atlanta,” wrote Aten. “The troops slept on their arms, and were startled during the night by what appeared to be terrific artillery firing in the direction of Atlanta…. We learned next day that the noise proceeded from the explosion of ammunition, the rear guard of the enemy having destroyed his abandoned ordnance stores as his army retreated from the city.”

On the morning of September 2, the Union Army looked out on the “wreck of a defeated enemy,” Aten wrote, “who had retreated during the night, leaving his dead unburied and his wounded uncared for.” Union and Confederate soldiers alike heard deafening explosions inside Confederate lines.

“About this time I heard a terrible roar,” recalled Private Robert Patrick, a Confederate soldier stationed in Atlanta. “At first I could not imagine what it was but after a time I ascertained that it was shells exploding.” What Patrick heard was the explosion of rail cars loaded with ammunition being destroyed to prevent their contents from falling into enemy hands.

“I could see how to walk for a long distance by the light of the shells and the burning cars,” wrote Patrick. “My road lay parallel with the track and as I approached nearer and nearer the burning train, the sound became deafening, and the fragments of shells hurtled through the midnight darkness over my head with an ominous rushing sound.”

What Patrick heard was the death knell of the western Confederacy. Mary Boykin Chestnut in Richmond, Virginia, echoed the feelings of the entire South when she noted in her diary, “Since Atlanta fell I felt as if all were dead within me forever.”

Hood would not give up but, from this time forward, nothing he could do would compensate for the loss of Atlanta. To force Sherman to abandon Atlanta, Hood would attack the Federal communications and supply lines north of the city. When that did not force Sherman to quit Atlanta, Hood moved into Tennessee, hoping Sherman would follow him. Sherman sent Thomas’s Army of the Cumberland and Schofield’s corps from the Army of the Ohio in a race to beat Hood to Nashville.

With no need to hold Atlanta, Sherman destroyed the city. On November 15 Sherman led his 62,000 men on devastating march of destruction to Savannah, arriving on December 10. Meanwhile, Thomas and Schofield successfully defended middle Tennessee against Hood. Schofield defeated Hood at Franklin on November 30, and Thomas won a decisive victory over Hood at Nashville in mid-December. At that point, the once great Confederate Army of Tennessee ceased to exist as an effective field army.

The war ground on for another seven months but, after the Battle of Jonesborough and the fall of Atlanta, there was no question that the North would prevail, and little doubt that Lincoln would win the 1864 presidential election.