By Christopher Miskimon

In the late afternoon of September 17, 1862 the 7th Maine Regiment received new orders. The Battle of Antietam had raged throughout the day. Thousands were dead and even more lay wounded on the field or suffering in hospitals behind the lines. After horrible combat at places known afterward as The Cornfield and Bloody Lane, the fighting climaxed at the lower bridge over Antietam Creek that historians called Burnside’s Bridge in memory of Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside who failed to capture it in a timely fashion. The 7th Maine was about to enter this action and its place in the history of the American Civil War.

Twenty-one year-old Major Thomas Hyde, a native of Bath, Maine, commanded the regiment. The regiment was part of Colonel William H. Irwin’s brigade of Maj. Gen. William Franklin’s VI Corps. The unit was seriously understrength that day. Only 181 men remained of its original complement of 1,000.

Hyde’s regiment had gone into action at the Bloody Lane and then taken up a position behind limestone outcroppings on the rolling hills west of Antietam Creek that afforded it a measure of protection from enemy fire. In that location the men dodged desultory enemy fire. When they could, the regi-ment’s marksmen sniped at enemy artillerists and officers.

Hyde and his men expected that when night arrived they would be relieved; however, like other regiments they lacked knowledge of how the battle was progressing. Irwin eventually issued new orders to Hyde. He told the major to lead his regiment in an attack against the Piper Farm where Lt. Gen. James Longstreet and Maj. Gen. Daniel Harvey Hill had cobbled together infantry regiments and batteries for a final stand following the Confederate retreat from the Bloody Lane.

Hyde believed the order was foolish. He told Irwin that an unsupported attack against such a position was tantamount to suicide. He felt a personal responsibility for his men and was unwilling to lead them in such a perilous attack. Irwin repeated his orders and then asked an insulting question meant to goad Hyde into leading the attack. “Are you afraid to go, sir?” asked Irwin.

Hyde wanted the men of the regiment to know that it was Irwin’s idea and not his own. “Give the order so the regiment can hear it, and we are ready, sir,” Hyde said.

The 7th Maine obeyed its orders and advanced toward the farm. Waiting to receive their attack were the remnants of four Confederate brigades from Hill’s division and Maj. Gen. Richard Anderson’s division.

The Rebels poured a deadly fire into the small group of Union soldiers. The Maine men found themselves trapped in farmer Henry Piper’s sprawling apple orchard. The repulse of Hyde’s regiment was over quickly. The survivors limped back to their previous position. Of the 181 men who participated in the attack, 12 were killed, 63 wounded, and 20 reported missing. Of the wounded, 13 succumbed to their wounds. They later learned that Colonel Irwin had been drunk when he sent them forward in such senseless slaughter.

The Battle of Antietam is full of such small stories, tales that combine to reveal the horror of one of the Civil War’s worst days. Antietam is remembered as the bloodiest day in American military history. Union casualties numbered 12,400 men, and Confederates casualties amounted to 10,320.

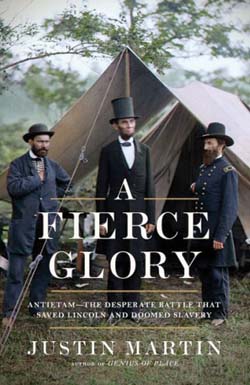

The Union Army won a strategic victory for it repulsed General Robert E. Lee’s first invasion of the North, forcing him to retreat shortly afterward to Virginia. But that victory had a high cost. The story of this dreadful battle is told in detail in A Fierce Glory: Antietam—The Desperate Battle That Saved Lincoln and Doomed Slavery (Justin Martin, Da Capo Press, Boston, MA, 2018, 336 pp., maps, photographs, notes, bibliography, index, $28.00, hardcover).

Although there are many books on the Battle of Antietam, this one stands out for its superb use of first-hand participant accounts. The author weaves the broader story of the battle into the work in a seamless manner. He also describes the role of famous noncombatants associated with the battle, such as nurse Clara Barton and photographer Alexander Gardner. In addition, the far-ranging consequences of the battle are discussed at length.

The result is a work that engages readers and retains their interest page after page. The book includes a useful section for visitors to the battlefield park, helping them understand the terrain in relation to the action. For these reasons, the book is a worthy addition to the works available on Antietam and the American Civil War.