By Eric Niderost

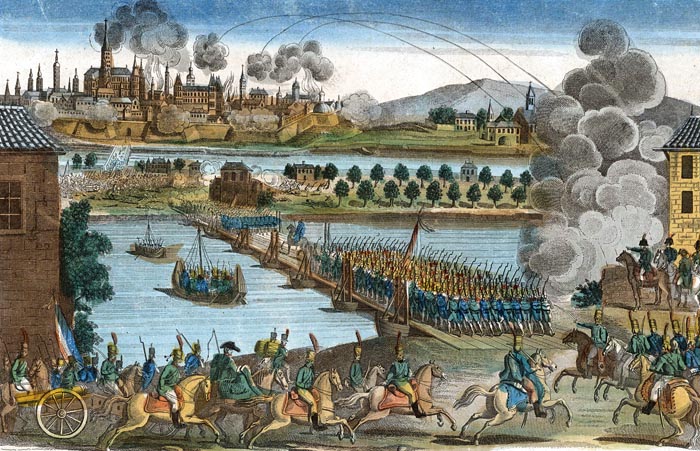

On the evening of July 4, 1809, Emperor Napoleon’s Grande Armee prepared to cross a narrow waterway from Lobau Island to Marchfelt, a large, flat plain that bordered the eastern banks of the sinuous Danube River. Marshal Nicolas Oudinot’s II Corps was among the first to attempt a passage, boarding boats with a minimum of delay and little or no confusion. No fewer than 6,000 grenadiers and voltigeurs had embarked, the men wearing white armbands to help identify French advance units and lessen the chance of friendly fire casualties.

Such identification was needed because, as the evening progressed, a storm developed that was both unseasonable and intense. French troops were lashed by a heavy downpour, a deluge of almost Biblical proportions accompanied by howling winds. French batteries on Lobau had opened a steady fire, their thunderous reports matched, and even surpassed, by peals of lightning.

French surgeon Dominique Jean Larrey, a veteran campaigner, recalled that troops were also pelted by hail, and “so intense was the darkness that we could only get our bearings during the flashes of lighting.” Some of the visibility problems were solved when French shells set the village of Gross Enzerdorf on fire. Flames engulfed the houses, the orange-yellow tendrils leaping so high into the air boatmen could get their bearings.

Once a foothold was firmly established on the eastern bank, French sappers went to work, rapidly putting preassembled bridges across the water. Once the spans were in place, the bulk of the Grande Armee began to cross. In spite of the weather and sporadic Austrian artillery fire, the whole operation went like clockwork. Shortly after 2 am, Marshal Nicholas Davout’s III Corps began crossing its assigned bridges without incident. His force included four infantry divisions and three cavalry divisions, altogether more than 30,000 men, yet all seemed to have made it safely across.

Somewhere in the pitch black awaited Archduke Charles von Hapsburg’s Austrian army, a force numbering 113,800 infantry, 14,600 cavalry, and 414 guns. Six weeks earlier Archduke Charles had pulled off something of a miracle when he defeated Napoleon at nearby Aspern-Essling. But the French emperor had not been decisively defeated and was now attempting to regain the initiative.

Knowing the fate of his empire was at stake, Napoleon supervised every detail of the operation. When Marshal Andre Massena’s IV Corps was about to cross, the squat emperor surprised the hard-working sappers by showing up at the bridgehead in person. A preassembled bridge was about to be swung across the channel. There were no fewer than 17 pontoons in the bridge, engineered to span a 178-yard gap. The idea was to swing the bridge across in one piece, a tricky and dangerous maneuver.

Napoleon, dressed as usual in his greatcoat and famed cocked hat, strode over to the officer in charge, a Captain Heckmann. His manner was brusk and to the point: “How long do you require for the swinging?” “A quarter of an hour, sire,” replied Heckmann. The emperor was not buying it. “I give you five minutes,” he snapped. Napoleon then turned to Henri-Gatien Bertrand, who was an engineering officer as well as an aide. “Bertrand, your watch!” he demanded.

The pontoon bridge managed to move flawlessly and all in one piece. It took eight minutes, but Napoleon was pleased enough to forgive the extra time. Still, there was not a moment to lose. Massena’s men began crossing at once, their boots sounding a rhythmic thud on the rough wooden planks. The marshal himself rode in a calash drawn by four horses from his own stables. His legs had been injured in a riding accident, so he could not walk or ride on horseback. Massena’s personal driver insisted on taking the reins, even though the carriage would be a perfect target for Austrian guns

By 10 am it was done: Napoleon’s army of 130,800 infantry, 23,300 cavalry, and 544 guns was safely across the Danube and poised for battle. There had already been some fighting that morning, savage and bloody, but still just a prologue of the main event to come. Who would prevail? The answer would determine the fate of Europe for some time to come.

The battle had its roots in the turbulent power politics of the period. Napoleon’s unrivaled genius on the battlefield led to peace treaties that too often humbled and humiliated his foes. Napoleon badly defeated Austria, once dominant in central Europe, in 1805 at Austerlitz. Afterward, Austria’s power was diminished and its reputation tarnished by a man who they considered an upstart at best. Filled with a burning desire for revenge, the Austrians bided their time, waiting for an opportunity to renew the contest.

The opportunity came early in 1809. Napoleon was in Spain, wrapping up a major campaign, and the French were taken completely by surprise. Archduke Charles was a competent if not overly imaginative general, and his first moves were good enough in this game of sanguinary chess. But check is not checkmate, and once Napoleon arrived on the scene the archduke was forced on the defensive.

For a time it looked like Napoleon was about to score another triumph. Vienna was captured, an important psychological blow, but victory would not be achieved until the Austrian army was vanquished. Archduke Charles wisely based his army north of the Danube, thus placing the great river between him and the Grande Armee. To attack the Austrians Napoleon would first have to cross the mighty river, no mean feat if his passage was contested. And once across, he might find himself fighting a major battle with the Danube at his back.

Napoleon responded to the problem with his usual thoroughness, at least it seemed so at the time. But by 1809 the emperor’s characteristic brilliance was being tainted by an all too human arrogance. He had come to believe in his own invincibility, and that, coupled with contempt for his foes, was to have near fatal results.

On May 20 Napoleon took a gamble. The French army crossed the river at Lobau Island, some four miles below Vienna, without adequate reconnaissance as to the enemy’s whereabouts. Worse still, the crossing depended on a single pontoon bridge that stretched a vulnerable 825 yards. The French managed to establish a bridgehead, but a vigorous attack by Archduke Charles on May 21 placed the whole Gallic operation in jeopardy.

The resulting fight is commemorated as the Battle of Aspern-Essling. It was a savage, two-day affair, and the French were hard pressed from the very beginning. Napoleon usually had the upper hand in battle, but this time the shoe was on the other foot. The French found themselves outgunned and outnumbered two to one, with reinforcements and ammunition conveyed over that single rickety bridge. The flimsy span was broken at least five times during the course of the battle, either by the Danube’s strong current or by Austrian fireboats.

The Lobau pontoon bridge was the French army’s lifeline, and when the bridge’s fragile beams parted, the French army was marooned. Finally accepting the inevitable, Napoleon ordered a general retreat to Lobau on the afternoon of May 22. It took time for such an amazing event to sink in. Although hard to fathom, Napoleon had been defeated in person.

The emperor himself was in something like a state of shock. For a good three days he was listless. His mind was seemingly paralyzed by the unaccustomed defeat. His mood was also darkened by the death of Jean Lannes, one of his best marshals and a close personal friend. But Napoleon’s energy and resolve soon returned, and he began planning for a comeback.

Napoleon knew that the French empire rested on shaky foundations, his continuing victories binding it together. If he sustained enough defeats, the whole grand empire would collapse like a house of cards. Russia, a nominal French ally, was more interested in nibbling away at Austrian territory than offering substantial help. And Prussia, dismembered and still smarting from its own defeat in 1806, also had to be watched.

But the emperor also had to contend with growing German nationalism. Austria and Prussia apart, the other German-speaking lands were growing restive under French domination. Napoleon’s Continental System, the economic blockade of Great Britain, was resented and brought hardships to German businessmen. Germany, formerly a patchwork quilt of approximately 300 petty states, had been consolidated into around 35 principalities, a French-driven process that ironically accelerated a pan-German feeling.

In spite of Napoleonic reforms, the Germans resented French rule, the presence of French troops, and French demands that they participate as allies in the emperor’s endless wars. They were restive, impatiently waiting for obvious signs of decline and defeat before rising up against the French occupiers. Napoleon had stumbled, but not fallen, that is, at least not yet. That is the reason the outcome of the next battle was of such vital importance. Napoleon had to win or risk losing everything.

As a first step the emperor temporarily withdrew all French troops from Lobau except Massena’s IV Corps. The island was then transformed into an entrenched camp, with strong fortifications bristling with at least 129 guns. More bridges were built, sturdy and strong, that linked Lobau to the mainland, but Napoleon realized the spans were in danger from fireboats or anything else the Austrians might place in the river to damage them. Taking no chances, the French drove poles into the riverbed upstream to catch any floating obstructions dumped into the Danube. Additionally, the Marines of the Guard manned 20 boats, an impromptu Danube River patrol to keep a watchful eye on things.

Napoleon was pleased with the continuing preparations; the bridges that linked the great river’s islands to the mainland were particularly noteworthy. The emperor, normally a hard taskmaster in war, could boastfully say, “The Danube no longer exists; it has been abolished.” At that point, it was simply a matter of concentrating all his forces for the projected knockout blow.

As the weeks went by Archduke Charles did little or nothing, as if he was mesmerized by his victory over the great Corsican. He did refortify Aspern and Essling and placed batteries that overlooked Lobau Island. More artillery was summoned for his field army, and the Landwehr (Austrian militia) was incorporated into his main forces.

Many reasons have been advanced for this delay. Some authorities suggest he was waiting for a German popular uprising against the French, but if he was, by late June he must have realized the waiting was in vain. Others suggest he was waiting for his brother, Archduke John von Hapsburg, and his army to join him. Unfortunately, a Franco-Italian army under Napoleon’s stepson Eugene de Beauharnais and General Jacques MacDonald soundly defeated the archduke at Raab in Hungary on June 14.

Napoleon poured over maps, studied every intelligence report, and analyzed every possible scenario. He had no intention of crossing the Danube in the same spot as he had in May, though it was obvious Charles must have thought he would. Aspern and Essling were fortified, and the approaches to the old French bridgehead were lined with Austrian cannons. There was the problem of Archduke John as well. Even though the archduke had been defeated and reduced in numbers, he still had enough men to tip the scales in Austria’s favor. Eventually he wound up in Pressburg, just 30 miles away from his brother’s main army. If Archduke John’s 13,000 men suddenly appeared on the Grande Armee’s flank, disaster might ensue.

Eventually a plan began to crystalize in Napoleon’s mind. First, he would give every indication that the French army would indeed cross where it had last May. Among other things, he moved his headquarters to the southwest corner of Lobau Island, an action that would be reported to Charles. Next, he sent General Legrand’s division over to the Muhlau salient, the one toehold the French still had on the Austrian-controlled side of the river, a passage that also included 36 guns. But this was only a feint to confuse Charles.

The real crossing point would be farther southeast. The village of Gross Enzerdorf would be the hinge by which the French army would wheel northwest, outflank the Austrian field guns near the old crossing, and simultaneously smash into the Charles’s left flank. At the same time, and this was the beauty of the plan, the French would impose themselves between the main Austrian army and that of Archduke John.

Ideally, Charles would rise to the bait, moving his army forward to the banks of the Danube, preparing for a rematch on the old battlefield, all the while not suspecting he was about to be hit in the flank and perhaps even the rear by a resurgent Grande Armee. Sure enough, Archduke Charles did move forward, at least initially, the white-coated Austrian troops marching through the lush grain fields that ripened in the blazing summer sun.

But Charles started to have second thoughts almost immediately. His troops were now within range of French guns, whose crews lost no time in bombarding the serried ranks. After spending all of July 2 in deliberation, pondering the best course of action, Charles ordered the bulk of the Austrian army to move farther from the river.

For Napoleon, these movements had both positive and negative aspects. On the negative side, the emperor could no longer outflank, and perhaps even smash, the entire Austrian army as he had hoped. Yet there was some good news too: a Danube crossing, once discovered, would not be hotly contested by Charles’s main force.

The new Austrian positions were not without merit, and in fact used the region’s geographical features to great advantage. Much of the Marchfeld was flat, with a rise or two that usually did not measure more than three feet. A meandering stream called the Russbach snaked its way through Marchfeld’s northern border, its steep banks lined with clusters of trees. The Russbach was truly a stream for it was only about 30 feet wide, but the trees and its banks made it an effective moat against cavalry and an impossible barrier for artillery.

Behind the Russbach there was some marshy ground, and after that, the most prominent feature of Marchfeld, the Wagram. The Wagram was an escarpment, a low ridge varying in height from about 60 to 98 feet that lay between the villages of Deutch-Wagram and Markgrafneusiedl. Making the most of this terrain, Archduke Charles placed his I, II, and III Corps on the escarpment behind the Russbach.

The forward positions in front of the Russbach, including the villages of Aspern and Essling, were held by the Austrian VI Korps and Austrian Advance Guard. Thoroughly out on a limb, these units were to delay the French as long as possible then fall back in good order. The VI Korps was then to withdraw to the Bisamberg, a high ridge near the Danube, while the Advance Guard was to retreat to Markgrafneusiedl.

Massena’s IV Corps was to make a great wheeling movement to the left, marching to a position northwest of Aspern at Britenlee. At the same time, Marshal Nicolas Oudinot’s II Corps would hold the French center, advancing to the Russbach just opposite Baumersdorf. The French right was assigned to Marshal Nicholas Davout’s III Corps, disciplined troops who were to move toward Markgrafneusiedl via Glinzendorf. Supporting troops included Prince Eugene’s Army of Italy and Marshal Jean Baptiste Bernadotte’s IX Corps, the latter consisting of Saxons allied to Napoleon.

As a reserve, Napoleon had his Imperial Guard, famed veterans whose bearskin caps were a symbol of French military prowess. He also had his reliable Reserve Cavalry under Marshal Bessieres. The Reserve was mostly cuirassier regiments, shock troops in steel helmets and breastplates and mounted on powerful horses. That did not complete the list of available units. Marshal Marmont’s XI Corps and the Bavarian troops under General Karl von Wrede were still on the Lobau and had not yet arrived at the front.

General MacDonald, son of a Jacobite exile, hoped to distinguish and rehabilitate his image in the unfolding battle. He leaned toward Republicanism, which made him suspect in Napoleon’s eyes. Worse still, he had been close friends with Jean Moreau, who was living in exile and regarded as one of the emperor’s greatest enemies. Attached to the Army of Italy as a kind of shadow adviser to Prince Eugene, MacDonald had been largely responsible for the latter’s triumph over Archduke John at Raab.

As the Army of Italy waited for the main action to start, Napoleon suddenly appeared on horseback. The Italian troops reacted to his presence by lifting their shakoes on the tips of their bayonets and repeatedly shouting, “Long live the emperor!” Napoleon acknowledged the cheers with a salute, but simply gave MacDonald a glance and rose on. MacDonald was somewhat crestfallen.

The first day’s fighting was heavy, see sawed back and forth, and was inconclusive. By 5 pm it seemed as if the battle would have to stop. Both sides had fought furiously most of the day, and some of Napoleon’s men, many of whom were still green conscripts having been called up to fill out the depleted ranks of the Grande Armee, were nearing exhaustion. But the emperor sensed he had momentum and was loath to end the day’s offensive. Bernadotte, Prince Eugene, Oudinot, and Davout would simultaneously assault the Russbach stream line between Deutch Wagram and Markgrafneusiedl and in so doing drive a deep wedge into the Austrian army. Once a breakthrough was achieved, it would be simply a matter of divide and ultimately conquer.

French artillery opened up about 7 PM, signaling the opening of a new and terrible phase of fighting. Baumersdorf, a village on the Russbach, had the misfortune of being near the Austrian center, which made it a primary target for French artillery. The village was held by the 8th Jager and Volunteers of the Erzherzog Karl (Archduke Charles) Legion, who stoically endured a hurricane of metal that soon set many of its buildings afire.

The artillery barrage was just the prelude to a full-fledged French infantry assault by men of Oudinot’s II Corps. The Volunteers and Jagers refused to yield, stubbornly defending Baumersdorf’s scorched ruins foot by foot, yard by yard. Marshal Oudinot decided on a different approach, namely a flanking attack on the village about 8 PM, the assignment given to the 57th Regiment of the Line and the 10th Legere.

The 57th was a famous regiment with roots dating back to the prerevolutionary Ancien Regime. They were renowned for their prowess in war, so formidable they were nicknamed “the terrible.” The blue-coated soldiers went forward with elan, but were met by Austrians with equal determination. Each shattered house, each rubble-choked building, became a fortress that had to be taken by storm.

The 10th Legere bypassed Baumersdorf, moving ahead to the main Austrian position. They waded the Russbach, passed through the viscous muck of the nearby boggy patch, and then ascended the escarpment just beyond. The climb was steep, and when the leading elements of the 10th Legere finally crested the summit they were disordered and probably winded by the effort.

Before they could recover from their exertions they met a brigade of whitecoats from II Korps in position on the escarpment. The Austrians leveled their muskets and unleashed a volley, a storm of lead that caused scores of French dead and wounded and left the survivors reeling. Before they could recover they were sent packing, and literally plunging, down the escarpment slopes by a cavalry charge of chevauxlegers (light cavalry) led in person by a sword-wielding Prince Frederick von Hohenzollern.

The first day’s battle finally concluded around 11 pm, mercifully ending the slaughter for the moment. Napoleon was in a fairly decent position, but it was obvious the long-sought decisive victory had eluded his grasp. And his ill-judged and ultimately ham-fisted dealings with the Iberian Peninsula were also coming home to roost. Napoleon had an army of 200,000 men occupying Spain, troops that could have been used to better purpose in Germany and Austria.

Because of his Spanish commitments, the quality and effectiveness of the Grand Armee was compromised. The infantry was especially diluted by too many conscripts and, because of manpower shortages, the French were forced to use German allied troops to a greater degree than in the past. There were several instances of raw troops breaking and running, though usually they did manage to rally and fight again. To be fair, there were a few instances of Austrian units taking to their heels as well.

Throughout the battle Napoleon kept his customary sang froid. At one point, an Austrian shell exploded so close to the emperor his horse shied. Oudinot, startled, said, “They are firing at headquarters!”

“Monsieur, in war all accidents are possible,” Napoleon dismissively replied. And even when conducting a high-stakes battle, Napoleon had time for a little humor to lighten the mood. When a staff officer had his helmet knocked off by a cannonball, “It’s a good job that you are not any taller!” the emperor said with a smile.

The next day, July 6, proved to be decisive. It was Archduke Charles who began the affair with a vigorous dawn offensive by Klenau’s VI Korps. One of his objectives was to crush the French left, while at the same time pushing on to the Danube to seize control of the Lobau bridges. If Charles could get behind the French army and cut off its means of supply and escape, it would be “marooned” and surrounded. It was a nightmare scenario for the French, and potentially an even greater disaster than Aspern-Essling. Napoleon himself might even be caught in the Austrian “net.”

The Austrians moved forward with pomp and real panache. Bands played as they marched, and the overall mood seemed to be one of supreme confidence despite some setbacks in the past. Certainly, they were no strangers to the terrain; the Hapsburg troops held frequent maneuvers at Marchfeld.

Marshal Jean Baptiste Bernadotte made matters worse by abandoning a key position, the village of Aderklaa, without orders to do so. Touchy, with a large chip on his shoulder, he tended to cover up his own failings by shifting the blame to others. In 1806 he failed to support Davout when the latter was hard pressed at Auderstadt, yet he tried to cover up his actions with bluster and bravado. The 1809 campaign was no different.

Bernadotte rode ahead of the fleeing troops to rally them, but in so doing happened to run into a very angry emperor. “I herewith remove you from command of the Corps you have handled so consistently badly,” the emperor snapped, adding, “Quit the Grande Armee within twenty-four hours.”

In the meantime, Klenau was making good progress battling his way through the French left, ultimately cutting Napoleon off from the Lobau bridges and his line of retreat. But the Austrian army was not noted for taking the initiative. General Klenau halted and began to patiently wait for support from the Austrian III Korps. He was only about three miles from the unprotected rear of the French army and the Lobau bridges, but he still stopped his progress, and in so doing the initiative passed to the French.

Napoleon saw the danger to his left and was going to deal with it in a decisive manner, but his main focus at the moment was on the right, where Davout was going to attack Markgrafneusiedl. Markgrafneusiedl was the key to victory, at least in the emperor’s opinion, and he was rarely wrong in these matters. In the meantime, Massena was ordered to turn and march south, his IV Corps coming to the rescue by stopping Klenau’s threatening advance.

To follow the emperor’s orders Massena had to execute a tricky and even perilous maneuver. He had to march across the face of the Austrian III Korps and Grenadier Reserve. By crossing the “T” with the Austrians at the bottom stem and the French the upper stroke, Massena’s men would expose their vulnerable flank to enemy artillery fire and perhaps even musketry.

Massena’s march would also be an agonizingly long five-mile trek. To divert the Austrians and gain some time, Napoleon ordered Marshal Jean Bessieres to attack with his heavy cavalry reserve. No fewer than 4,000 armored warriors rode past Napoleon, and as they went their galloping steeds produced a thunderous tattoo, a rumble that was punctuated by fervent cries of “Vive l‘Empereur!”

Napoleon, acknowledged their salute, but shouted additional orders over the din: “Ne sabraz pas: pointez, pointez.” This translates to “Don’t slash with your swords, use the points of your weapons instead.” The charge was a magnificent spectacle, full of pride and panoply, and their breastplates and backplates evoked memories of medieval knights. But this was the early 19th century and not the Middle Ages. Austrian artillery opened up at once, cutting bloody swathes into the advancing horsemen. Men and horses were eviscerated, disemboweled, turn to gory heaps of human and animal flesh, but the cuirassiers would not be dissuaded from their task.

Bessieres, a leader of Napoleon’s Imperial Guard, habitually wore the uniform of the Guard’s Chasseurs a Chaval. He wore his hair unfashionably long and so was easy to spot on the battlefield. The marshal shared his men’s misfortune: first, his horse was killed out from under him, and then, moments later, an apparently glancing blow from a cannonball wounded him. When Napoleon heard that Bessieres was out of action, he ordered that the news be suppressed as much as possible. The marshal was a popular man. He would later recover.

The gallant charge was not in vain, because it did indeed buy valuable time. It bought enough time for Napoleon to bring his grand battery forward. The grand battery consisted of 112 guns, with some artillery coming from the Imperial Guard and some pieces from the Army of Italy. Forming a wide arc, the French artillery soon started pounding the area between Aderklaa and Brentenlee. Cannons belched gouts of flame and smoke with each discharge as sweat-drenched gun crews worked their pieces with clockwork regularity.

The grand battery had essentially the same mission as the cavalry: protect and support Massena’s risky move south. The battery proved more effective than the cavalry, tearing great holes in the packed ranks of the whitecoats. Shells ripped into soldiers, sometimes flinging their shattered bodies up in the air, and cannonballs took off heads, arms, and legs with horrifying ease.

Desperate to find some shelter from this man-made maelstrom, elements of the Austrian III Korps retired to the Breitenlee-Sussenbrunn road. For the moment, the situation had stabilized, leaving Napoleon to concentrate on capturing the all-important key to victory, the village of Markgrafneusiedl. Davout stormed the village without hesitation, but it was soon apparent that it was going to be a hard nut to crack. Austrian defenders fought for every inch of ground. Markgrafneusiedl’s cluster of stone houses became fiercely contested strongpoints, and other landmarks, like the windmill, monastery, and an old moated church, were fortresses often to be taken not just by bullets, but by the cold steel of bayonets.

Napoleon also desired an attack on the Austrian center. If the attack on the center succeeded, it would split Charles’s army in two; if not, it would still tie up and divert the Austrians, preventing them from sending reinforcements to the hard-pressed defenders of Markgrafneusiedl. The emperor chose MacDonald and his Army of Italy for this crucial task.

MacDonald formed his men in a gigantic hollow square of 8,000 men. In his memoirs MacDonald claims that, at least in part, the formation was used because of the threat of Austrian cavalry attacks, though he did have French horsemen with him as well. Perhaps the general didn’t want to admit that unseasoned troops fought better in larger formations, and the chances of their taking to their heels was reduced, if not altogether eliminated.

Drummers beat the pas de charge, a throbbing, rhythmic tattoo that could be distinctly heard over the sounds of battle. MacDonald’s great square was a perfect target for Austrian artillery, and soon great bloody gaps were torn in the blue-coated ranks. Whole bunches of men were cut down simultaneously, but survivors were ordered to close and dress their ranks as if on parade.

MacDonald’s column was like a great wounded beast staggering along, leaving a bloody trail of entrails, which were the broken bodies of its dead and wounded soldiers, in its wake. French cuirassiers and cavalry of the guard gave support, but they could not protect MacDonald’s cumbersome formation from the artillery barrages that tormented and lacerated them with each step.

MacDonald’s long-suffering troops had not achieved a breakthrough, but their secondary purpose, that of preventing reinforcements to Markgrafneusiedl, succeeded. Napoleon, who scanned the horizon with his telescope from horseback, saw that Davout’s firing line had passed the village’s church tower. It was plain that Markgrafneusiedl would fall to the French, and soon. Satisfied, the emperor snapped the telescope shut. Massena was making good progress on the right, and by 2 pm Klenau, his get-behind-the-French-army maneuver in tatters, was forced out of Aspern.

With his right and left crumbling, and his center barely holding, Archduke Charles was in real despair. His brother Archduke John, the man whose arrival would have tipped the battle in Austrian favor, was nowhere to be seen. In a hopeless mood and suffering from a slight wound, Charles reluctantly ordered a general withdrawal.

Napoleon had his victory, but the French were simply too exhausted to mount an effective pursuit of their enemy. Sadly, the French army lost another one of its legendary paladins when 33-year-old General of Division Antoine de Lasalle, a renowned hussar commander, was shot dead at the head of his troops.

Napoleon had won the Battle of Wagram, but as Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington, once said of his victory over Napoleon at Waterloo, it was a near-run thing. Wagram, in truth, was something of a pyrrhic victory if one looks at the statistics: 30,000 casualties, 4,000 captured, and 11 guns and three eagle standards lost. In comparison, the Austrians suffered 23,000 casualties and 18,000 captured. Yet the Austrian lost only nine guns and one standard, which was mute but eloquent testimony of the Austrians’ newly learned discipline and training.

Nevertheless, the French emperor had bested the Austrians and regained his prestige. Austria capitulated, since the Treaty of Schonbrunn, signed in October 1809, was yet another punitive pact that left the Austrian empire reduced in territory and prestige. Besides the loss of territory, Austria had to pay an indemnity and honor the Continental System; thus, it was not peace, but a protracted pause before the next round of fighting.

MacDonald won his long-coveted marshal’s baton, and the honor was made even sweeter by being awarded on the field of battle. Napoleon embraced MacDonald, declaring. “On the battlefield of glory, where I owe you so large a part of yesterday’s success, I make you Marshal of France.”

The next three years after Wagram saw Napoleon at the height of his power. But the Austrians had fought well, in part because of a rising patriotic, nationalist feeling, and also they adopted some of the organization and techniques of the Grande Armee. That, as well as the lowering of the overall quality of the French army, meant that relatively easy triumphs such as Ulm, Austerlitz, and Jena would not be repeated.

Sometime later, when someone criticized the Austrian army within earshot of the emperor, he snapped, “It is evident you were not at Wagram.”