By Bruce Petty

More than 16 million Americans served in the U.S. military during World War II, but as fluid as the situation was in the Pacific, and considering the priority given to the European Theater, it is difficult to obtain an accurate count of how many served in the Pacific at any one time during World War II. However, thanks to historians who have given attention to the demographics of the war, it is estimated that at least three million Americans served in the Pacific by war’s end.

Throughout much of its history, the United States Navy has depended on graduates of the U.S. Naval Academy to fill its needs for qualified officers. However, the Naval Academy itself was not established until 1845, just six years before the commencement of the American Civil War. Before that, officers in the U.S. Navy, in imitation of the British and other navies, trained future naval officers on the job as seagoing apprentices, better known as midshipmen. The first class of midshipmen to attend the Naval Academy consisted of just 50 men. Today the academy graduates closer to 1,000 men and women every year.

With the outbreak of the American Civil War, the biggest war in U.S. history to date, the Navy suffered from a shortage of officers. Not only did the Naval Academy not produce enough officers for a rapidly expanding Navy, but also a large number of both commissioned officers and midshipmen swore allegiance to the Confederate Navy; and with the U.S. Navy heavily involved in blockading the southern states, this left the North in a difficult situation which was not completely rectified until after the war was over.

World War I created more difficulties for the U.S. Navy in that this war, the first fought on such a large geographical scale, proved that the Naval Academy alone could not produce adequate numbers of officers for a navy about to fight a global war. As a result, following the lead of the Army, the Navy experimented with the idea of educating and training officers outside the Naval Academy. In 1925, both the Congress and the president approved the establishment of a Naval Reserve Officer Training Program (NROTC). Six universities were selected for this experimental program, which started in the fall of 1926. They were the University of California at Berkeley, the University of Washington, Harvard, Yale, the Georgia School of Technology, and Northwestern. During World War II, 12 percent of the officers who served were graduates of NROTC programs.

The first commander of the NROTC Program at Berkeley was then Commander Chester W. Nimitz. He was not only the commander of the program, but also taught naval science to the cadets. One of the graduates from the NROTC program at Berkeley was William C. Meyers. Meyers was born in Ukiah, California, in 1913. However, his family eventually moved to the Berkeley/Oakland area of California, where young Meyer went to school. He came to know Commander Nimitz at this time because he went to school with and became friends with his son, Chester, Jr., who also became a naval officer and served in submarines as his father did in the early days of his naval career.

Meyer also came to know the Nimitz family through his father, who for a number of years assisted Nimitz by teaching navigation to the NROTC cadets who attended Berkeley. Later, in 1930, no doubt influenced by both his friendship with Chester Jr. and his father’s friendship with Chester Sr., Meyer applied for entrance to U.C. Berkeley and the NROTC program and was accepted to both. Upon graduation he received a commission as an ensign in the U.S. Naval Reserve. He worked for a number of years as a civilian engineer, but in 1939 his naval reserve unit was put on alert for possible mobilization. The war in Europe had started, but Pearl Harbor and American’s entry into the war were still two years away.

Although on alert, Meyer continued at his civilian job until late 1940, when he received orders to report to the stores ship USS Aldebaran (AF-10). The skipper of Aldebaran was Captain Royal W. Abbott, a Naval Academy graduate. According to Meyer, he was “by the book,” and “good, but strict.” And being an academy man, he did not trust reservists. He observed these young reservists every minute they were on watch. He went so far as to have a rearview mirror installed on the bridge so that he could see what they were doing behind him. “I don’t think he ever came to trust us in the entire year that I was aboard,” Meyer remembered.

During his time aboard Aldebaran, young Meyer and the rest of the crew were kept busy running supplies from the West Coast to Hawaii to meet the needs of the Pacific Fleet recently moved there from the West Coast. In the late summer of 1941, Meyer and the rest of the crew still aboard Aldebaran had a break from their routine and took cement, some 6-inch coastal defense guns, ammunition, and other materiel to Pago Pago in American Samoa. Pago Pago is the only natural deepwater port in that part of the Pacific, and the United States was preparing for its defense in case war broke out with Japan, something U.S. military planners had been preparing for since the early part of the century.

Back in Hawaii from her mission to Pago Pago, Aldebaran prepared to resume her routine of running supplies from the West Coast to Hawaii. The ship departed Hawaii on December 1, 1941, and arrived in San Francisco on December 6. Of course, on December 7, in Hawaii, the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. There was nothing routine about Meyer’s time in the Navy after that.

Sometime late in December, Meyer heard about a new type of ship that the yards were constructing for the Navy, something smaller than a destroyer, even smaller than a destroyer escort. It was a patrol craft. They were so small and so many were built during the war that they were not even given names. They were simply called PCs for short and given numbers.

At this time, literally just weeks after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, Admiral Nimitz had yet to replace Admiral Husband Kimmel as commander of the Pacific Fleet in Hawaii. He was still Chief of the Bureau of Navigation and less than a household name. Meyer then wrote a personal note to Nimitz (the last time he would feel free to do so for the rest of the war) asking about this new type of craft and also wanting to know if he could get assigned to one of them. Not long after sending the letter, Meyer received orders to report to New Orleans, where he found USS PC-476. She was 173 feet long, had depth charges, sonar, and one 3-inch gun, but no radar. She was designed for antisubmarine warfare, but like a lot of other types of vessels, would perform a multitude of tasks.

To his surprise, not only had Meyer been assigned to this new type of craft, but he was also the ship’s new skipper. He was a lieutenant (j.g.), and to help him launch his first ship he had two other officers, both “Ninety-Day Wonders” fresh out of college. Ensign R.D. Butler and Ensign D.P. Wilber had just graduated from the NROTC program at Northwestern University, and neither one had ever been to sea before. They, like thousands of others, were going to help win the war.

In addition to the three officers aboard PC-467, there were 44 enlisted men. Half of them were reservists recently called to active duty, and the rest were regular Navy. Meyer’s chief engineer was a machinist mate first class by the name of J.G. Rivers. All of his experience was with steam engines, but the PCs were powered by two General Motors diesel engines. In those desperate early months of World War II, there was no time to send men off to school to learn how to maintain those diesel engines. Rivers, like many others, turned to the owner’s manual and taught himself. And the regulars mentored the reservists to bring the ship up to fighting standards. Likewise, Meyer was impressed with how willing and how fast his two young NROTC neophytes assimilated and learned their responsibilities.

In the spring of 1942, PC-476 was assigned to accompany the escort aircraft carrier USS Long Island (CVE-1), through the Panama Canal to the West Coast and out to Hawaii. It was accompanied by PC-477 and a World War I-vintage, four-stack destroyer. When they arrived in Hawaii, as requested earlier by Meyer, a fourth officer joined the ship. Ensign W.G. Anderson was another NROTC graduate.

After a few months in Hawaii, PC-476, PC-477, and PC-479 headed for the South Pacific. They went via Palmyra Island and American Samoa, where they refueled before arriving in New Caledonia. In October 1942, they were ordered to Guadalcanal where they guarded the beaches off Lunga Roads against enemy submarine attack.

The PCs were stationed at Tulagi, across Iron Bottom Sound from Guadalcanal, as were the PT-boats. In early December 1942, during the waning days of the Japanese effort to resupply their starving troops on Guadalcanal, the PTs participated in a battle off Cape Esperance. During the battle, they sank the Japanese destroyer Teruzuki with Rear Admiral Raizo Tanaka, the squadron commander, aboard. The following day PC-476 was ordered to rescue one of the PTs that had run aground off Cape Esperance. On the way, they found a ship’s boat from Teruzuki abandoned and dead in the water. PC-476 towed it back to base. Aboard was found a suitcase with an admiral’s uniform, plus his sword and dagger. Also in the suitcase was a roll of maps showing all of the American gun positions on Guadalcanal. These were turned over to the Marine Corps. Meyer kept the sword and dagger. It was only later that Meyer found out that they belonged to Tanaka, who was rescued without his belongings and went ashore on Guadalcanal. At the time, Meyer knew nothing about Tanaka. This all came to light after the war.

In early January 1943, Meyer and PC-476 were ordered to rendezvous with the submarine USS Nautilus off the coast of Santa Isabel Island in the Solomons. With the help of some coastwatchers, Nautilus had rescued some Catholic nuns originally from Long Beach, California, and some plantation owners and their families. PC-476 successfully rendezvoused with Nautilus in the dead of night without the help of radar and transferred more than 20 civilians, delivering them safely to Guadalcanal. From there they were transported to New Zealand and then on to their respective home countries.

With Guadalcanal secured, in June 1943 Meyer was relieved of command and sent back to the States, where he took command of a new destroyer escort, USS Newman (DE-205). Newman, with Meyer in command, operated in the Atlantic and Mediterranean doing convoy duty until June 1944. He then took command of a high-speed destroyer transport, USS Ringness (AP-100), named after a doctor who had lost his life on Guadalcanal.

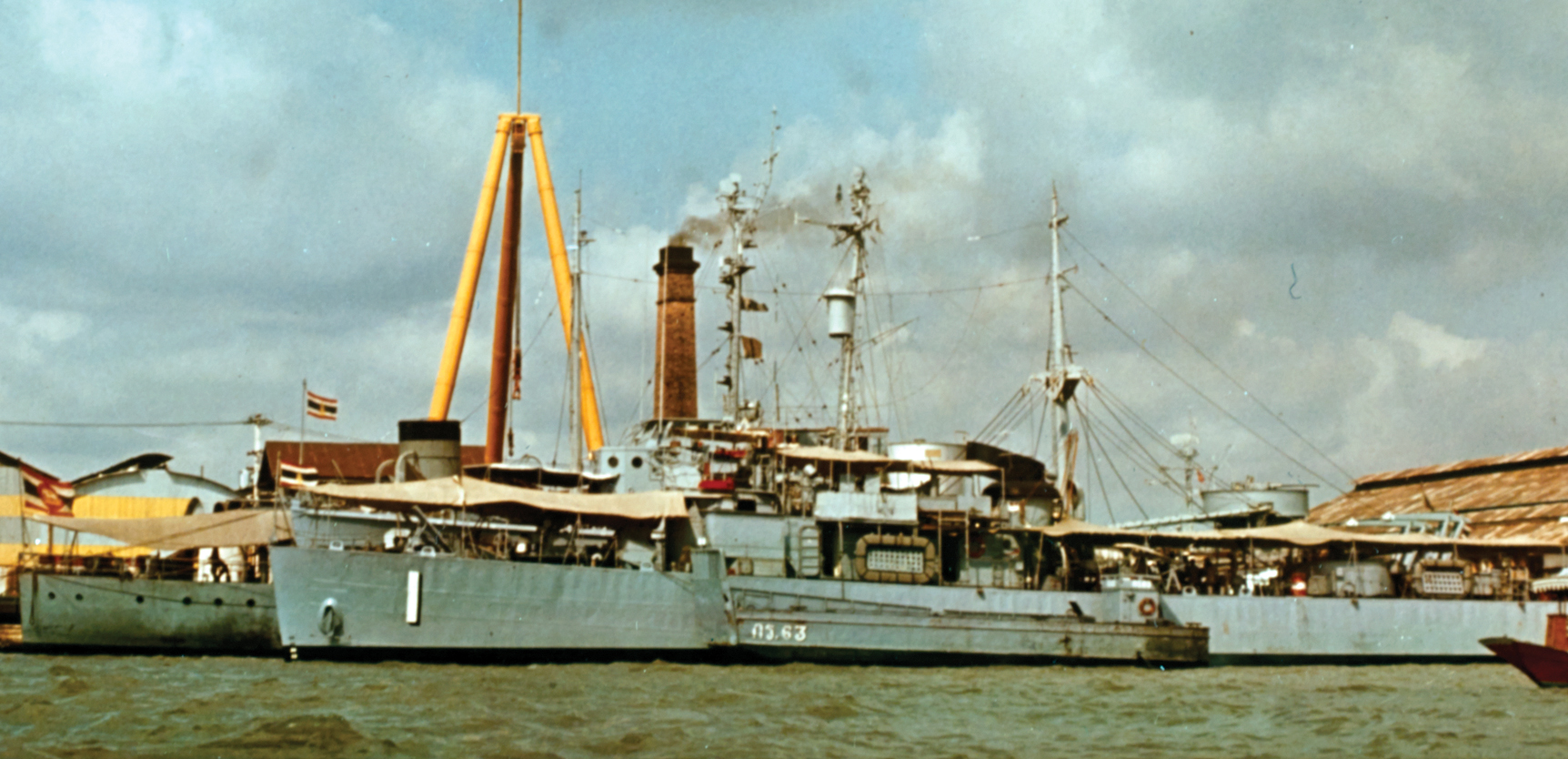

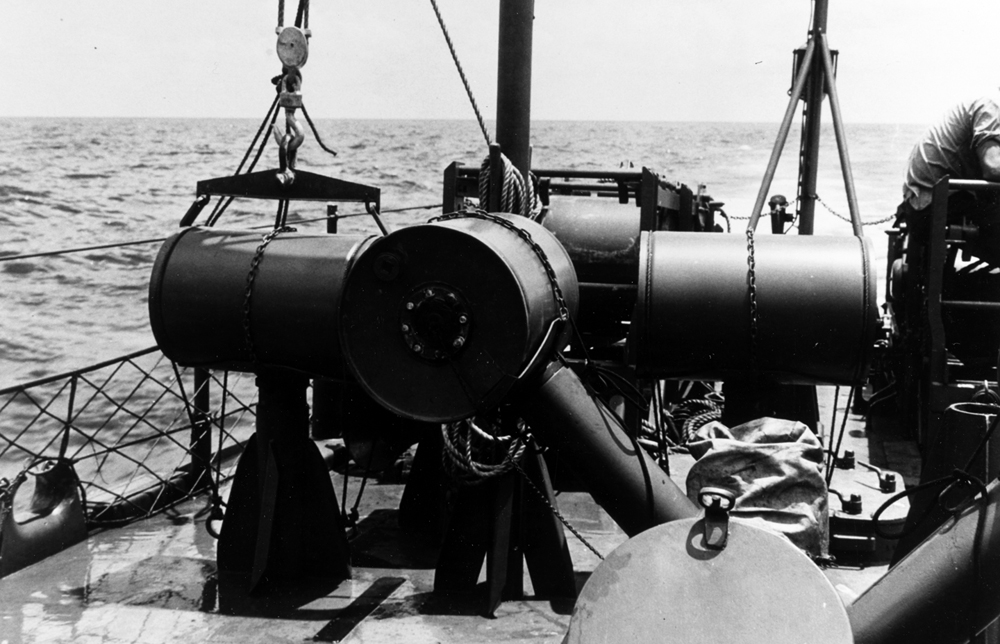

Ringness carried four landing craft and could also transport up to 150 troops for amphibious landings. From the East Coast, Ringness headed for the Pacific to join Task Force Baker at Guadalcanal in preparation for the landings on Okinawa in April 1945. She also had 5-inch guns, depth-charge racks, and hedgehogs, throw-ahead weapons used against submarines. Ringness also had sonar, and although designated as an attack transport she was also used as an escort vessel. During the Okinawan operation—the last battle of World War II—she served as a picket, giving warning to the main fleet of incoming Japanese aircraft, most of which were kamikazes. During this time, Ringness was involved in rescuing survivors of ships that had been hit.

Then one morning at around 0200 hours while the ship was on picket duty in the far northwest of Station 15 on the line, a kamikaze aimed for Ringness. When it was around five miles out, according to her radar, Meyer ordered up flank speed and purposely did not open fire on the attacking plane, knowing that the gun flashes would give the attacking pilot a definite target. As a result, the plane narrowly missed the stern of Ringness and crashed into the sea.

After Okinawa, Ringness was ordered to the Philippines to train for the planned invasion of the Japanese home islands. Her task was to carry in underwater demolition teams (UDTs). However, during her training she was pulled to accompany escort carriers to Ulithi Atoll. This was in late July 1945, and on August 2, on the way back to the Philippines Meyer received a message that read, “SURVIVORS IN THE WATER. PROCEED AT BEST SPEED TO EFFECT RESCUE!”

The survivors, as Meyer was to learn, were from the heavy cruiser USS Indianapolis, which only days before had dropped off part of the first atomic bomb at the island of Tinian in the Marianas. From Tinian, Indianapolis sailed to Guam and then headed west for the Philippines. The cruiser was without escort even though the captain of Indianapolis, Charles B. McVay, III, had requested one. The Japanese submarine I-58 sighted Indianapolis just before midnight on July 29 and sent her to the bottom. By the time Ringness and other rescue ships arrived on the scene several days later, only 316 of the original 1,199 officers and men were still alive to be rescued.

Ringness was one of the first ships to arrive on the scene, and as luck would have it one of the first people she pulled out of the water was Captain McVay. He was with a group of survivors clinging to three life rafts that were tied together. McVay was later court-martialed for not zigzagging his ship. He was also the only captain in the history of the U.S. Navy to be court-martialed for losing his ship in combat. His career was over, and in 1969 he committed suicide.

Those who served aboard Ringness are considered members of the Indianapolis Survivors Association, and for years after the war attended not only their own ship’s reunions, but also those of Indianapolis.

Meyer never saw Admiral Nimitz during the war, but afterward he did elect to stay in the Navy and transferred from the reserves to the regular Navy. Their paths crossed again where they had first met back in the 1920s when young Meyer became friends with Chester Jr. Captain Meyer ended up back at U.C. Berkeley after the war, where he was a professor teaching naval science to a new generation of NROTC students. It was not uncommon for then retired Admiral Nimitz, living in Berkeley at the time, to call Meyer and say, “Meyer, bring a couple of midshipmen up here. I want to play some horseshoes!”

Meyer would then bring a couple of midshipmen over to play horseshoes with the admiral while Mrs. Nimitz baked fresh bread. They would all then sit in the living room, eat fresh baked bread, and chat with the admiral. Nimitz died in 1966, and Captain Meyer retired from the Navy two years later.

Bruce Petty is the author of five books, four of which concern World War II in the Pacific. He is a resident of New Plymouth, New Zealand.