By Arnold Blumberg

Despite being caught up in the tide of isolationism prevalent duringthe interval between the world wars, the United States Army was lucky enough to have Congressional funding for the further development and expansion of its fledgling air arm, known initially in 1926 as the Army Air Corps and in 1941 renamed the Army Air Forces. The potential of air power, as exhibited during the conflict of 1914-1918 and hinted at by the rapid technological advancements in aircraft designs and capability in the two decades after that conflict guaranteed its participation in future wars, assuring its inclusion in all the military arsenals of the world’s major powers, including the United States.

Throughout the period, the U.S. Army procured and tested new tactical aircraft, built bombing and gunnery ranges, created training and tactical doctrine, and finally, the Air Corps built a worldwide aircraft communication system that emphasized air-to-ground and ground-to air capability. Although the Air Corps had mostly tactical aircraft in its inventory during the interwar years, it nevertheless stressed as part of its training and doctrine an ever-widening role for aerial reconnaissance and observation.

Problems did surface between U.S. Army aviators and ground commanders about what constituted observation and reconnaissance from the sky. Part of the ongoing disagreement was the issue of what type of planes should be used to execute those tasks. One school of thought that took hold among the Army hierarchy was that aerial observation should be limited to the immediate or adjacent battlefield areas and used mainly for the adjustment of friendly artillery fire. This approach called for the use of slow-flying machines that could loiter over the target area for the maximum time possible. Detractors of this theory, mostly Air Corps officers, argued that such aircraft designs would be at the mercy of enemy antiaircraft as well as small arms fire and susceptible to fighter attack. They went on to claim that the slow, unarmed observation craft would need friendly escort fighters with them over the target area to make sure the mission was accomplished. These conflicting concepts continued unabated into World War II.

When America was plunged into World War II on December 7, 1941, the country was woefully unprepared. Its Army numbered merely 190,000 troops, including the Army Air Corps, and much of its weaponry was outdated. Major military maneuvers of 1941 and 1942 were designed to test new weapons and new doctrine. It was during these exercises that the U.S. Army decided to test the reliability and capability of certain aircraft to be used for aerial observation and artillery spotting. Once again, the Army Air Corps and the Army ground forces clashed over what type of aircraft should be designated for these jobs. The former continued to promulgate the thesis that observation missions required modified combat aircraft due to the need to perform aerial reconnaissance with the least risk as possible from hostile fire, whether originating from the ground or the air. The latter view, as espoused by the Army ground forces, favored a small, lightweight, and inexpensive machine to serve solely as a vertical extension of an artillery observation post. These aircraft, in their opinion, would not be required to penetrate far beyond the enemy’s front lines.

With its goal in mind, the Army ground forces proceeded to test the effectiveness of small aircraft for artillery spotting, aerial observation, command control, communication, wire laying, and medical evacuation. In the summer wargames of 1941, the Army tested commercially built aircraft designs that were unofficially designated liaison or “L” aircraft. The term became official during the April 1942 military maneuvers. Equipped with two-way radios, these two-seater single-engine craft were manned by a pilot and an observer.

Commercial aircraft manufacturers such as Piper, Taylorcraft, and the Stinson Division of the Consolidated Vultee Aircraft Corporation built the liaison aircraft used by the Army ground forces in World War II. Piper built the ubiquitous L-4, which was one of the primary observation planes used by the Army during the war, while Taylorcraft supplied the L-2 and L-3 models, essentially variants of the L-4. In 1943, Consolidated Vultee produced the L-5, which was based on the other L series models but was the only designed and purpose-built military observation aircraft used by the United States during the entire war.

The “L” planes variants were inexpensive, easy to operate and maintain, aerodynamically sound, and could land almost anywhere, which earned them the nicknames “puddle jumpers” and “grasshoppers.” By February 1942, the Army had 1,600 of these on order with the condition that they were to be used mostly for artillery spotting and remain 1,800 yards within friendly territory when on a mission. Subsequent Army regulations allowed pilots to determine for themselves what constituted 1,800 yards of friendly ground. This was a wise directive since World War II liaison pilots were very often too preoccupied dodging enemy antiaircraft fire to determine the friendly land boundaries within which they were supposed to stay.

On June 6, 1942, an organic Army aviation program was established. This provided Army ground forces with two pilots and one aircraft mechanic for each field artillery battalion and additional one or two pilots for the artillery headquarters. Each Army division was slated to have a minimum of six pilots and six planes to a maximum of 10 pilots and 10 aircraft. This number would be raised by the end of the war to 16 aircraft per Army division. During the war the Army Air Forces were given the responsibility for the procurement of liaison planes, spare parts, repair materials, and all auxiliary flying equipment.

In early 1942, the Army established the Department of Air Training at Fort Sill, Oklahoma, and in June of that year began to organize organic Army aviation. The department’s function was to train pilots to fly fire adjustment missions for the Army’s field artillery. Lt. Col. William F. Ford, both an artillery officer and a certified pilot, was selected to be the organization’s first director. In addition to Fort Sill, flight training was also carried out at Pittsburg, Kansas, and Denton, Texas. By the close of the war several thousand pilots had passed through the department’s training facilities. The first class began the course work at Fort Sill on August 1, 1942, and comprised 19 students. It finished its training on September 18 the same year. The first five classes at Fort Sill were made up of officers and enlisted men from the Army ground forces and the Army service forces. During 1943, however, the Army discontinued bringing enlisted men into its organic aviation program because its needs were such that qualified enlistees were being sent to officer candidate schools to fill vacancies in the armor, artillery, and infantry branches. As a result, fewer pilots were trained, but the Army made up for this shortfall in pilots by using the training slots for liaison aircraft mechanics. Liaison pilots were in turn given some cursory maintenance training to allow them to make simple repairs to their planes in the field.

On November 9, 1942, three Army liaison L-4s, under the command of Army Captain Ford E. Allcom, took off from the deck of the aircraft carrier USS Ranger cruising off the coast of North Africa during the opening phase of Operation Torch. This signaled the first combat mission ever undertaken by U.S. Army liaison aircraft. The little planes had no problem lifting off the carrier and then proceeded to a landing strip near the coast, all the while maintaining radio silence. While over the Allied invasion fleet, the planes were mistaken for German aircraft and were shot at. Taking evasive action, Allcom’s flight continued to head for the coast, where he was fired on again, this time by antiaircraft gunners of the U.S. 2nd Armored Division, believing the American flyers were German. With part of his cockpit shot away by the friendly fire, Allcom managed to land safely only to be wounded by machine-gun fire from Vichy French forces. The captain was fortunate enough to be aided by area civilians, who rushed him to a U.S. Army aid station for treatment.

A number of significant problems arose from the use of liaison aircraft during the North African campaign. The most troublesome was that there were not enough planes to effectively set up a workable artillery-spotting regime. Many times, the available planes were employed for other purposes such as command and control and communication missions, thus reducing their use for their main job of providing needed artillery adjustment for infantry and armored units. A second critical problem was the shortage of trained aerial observers. This caused some ground commanders to try to solve the issue by hastily training rear echelon personnel—cooks, clerks, infantry, and artillerymen—to be flight observers. The lack of results was predictable, and the chronic shortage continued throughout the North African operation. It was not until late 1943 and 1944 that the Department of Air Training addressed this issue by greatly expanding its training of observers.

A third problem reared its ugly head in the form of the very apparent antagonism between the Army ground forces and the Army Air Forces over what constituted aerial reconnaissance and battlefield observation. The latter branch pressed the issue of the difficulty of liaison air assets being able to perform battlefield observation due to their vulnerability to enemy air and ground fire. Lt. Gen. Carl W. Spaatz, the Army Air Forces commander in North Africa responsible for the Allied tactical and strategic air operations in that theater, felt that close air-ground support and aerial reconnaissance could only be maintained by gaining air superiority over the German Luftwaffe. To him, this required the use of Allied fighter planes to fly cover for high-speed photoreconnaissance aircraft that were capable of both observing and photographing enemy ground activity. Since the Army ground forces did not have this ability, control of aerial reconnaissance and observation by default fell to the Army Air Forces. The result was that now the former branch could concentrate on conducting artillery fire-adjustment missions.

As the Army ground forces and Army Air Forces had conflicting ideas about who should have and employ liaison aircraft during World War II, the latter had never been favorably disposed to the former having organic aviation units and believed it should be responsible for all the U.S. Army’s aviation requirements. The two branches based their divergent views on the use of liaison aircraft on their differing views regarding doctrine over that use. For example, in early 1944, Commanding General of the Army Air Forces Henry “Hap” Arnold and Lt. Gen. Lesley J. McNair, head of the Army ground forces became embroiled in a controversy about whether liaison aircraft should be under the authority of the Army Air Forces. General Arnold cited the North African and Sicilian campaigns as examples of what he deemed the misuse of L-4s in combat. He stated that General Spaatz felt the Army needed a liaison design that had higher performance capabilities than the L-4. He went further and claimed that there had to be better coordination between ground commanders and the aircraft providing close ground-air support. Arnold felt that both of these could be achieved if Army Air Forces pilots and liaison pilots took turns flying as pilot and observer on these missions, during which the observer would call in the mission to the combat strike aircraft providing close ground-air support after receiving ground coordinates from the ground commanders.

General Arnold stressed that liaison planes should have no less than 100-horsepower engines, which would better align them with the speed of friendly fighters and fighter bombers. He got his wish with the introduction into service in the spring of 1944 of the 190-horsepower Stinson L-5 liaison design. He went on to push for the Army Air Forces to control all artillery spotting and liaison missions and have these tasks phased out of Army ground forces responsibility.

On February 16, 1944, General McNair issued a rebuttal to Arnold’s proposed plans for revamping the aerial reconnaissance and observation responsibilities. McNair reiterated the premise that the Army ground forces retain control of its own aircraft since ground commanders would be in a better position to decide how and when to employ liaison air assets than air force commanders. McNair continued his argument by stating that the War Department had created the ground forces air element with the acquiescence of the Army Air Forces because the latter recognized its inability to properly perform battlefield aerial observation and artillery adjustment fire. Regardless of the back and forth arguments issued by both sides, there was no immediate resolution of the doctrinal impasse between Arnold and McNair.

Later in the summer of 1944, the War Department reviewed the positions of both sides of the issue and accepted the stand of the Army ground forces. However, the War Department granted the Army Air Forces the right to have its request to have a larger role in liaison missions reexamined in the event organic Army aviation was expanded during the war. Such an expansion did occur in 1945, but the War Department, because Japan had surrendered, never did address the Army Air Forces petition for such a review when it came.

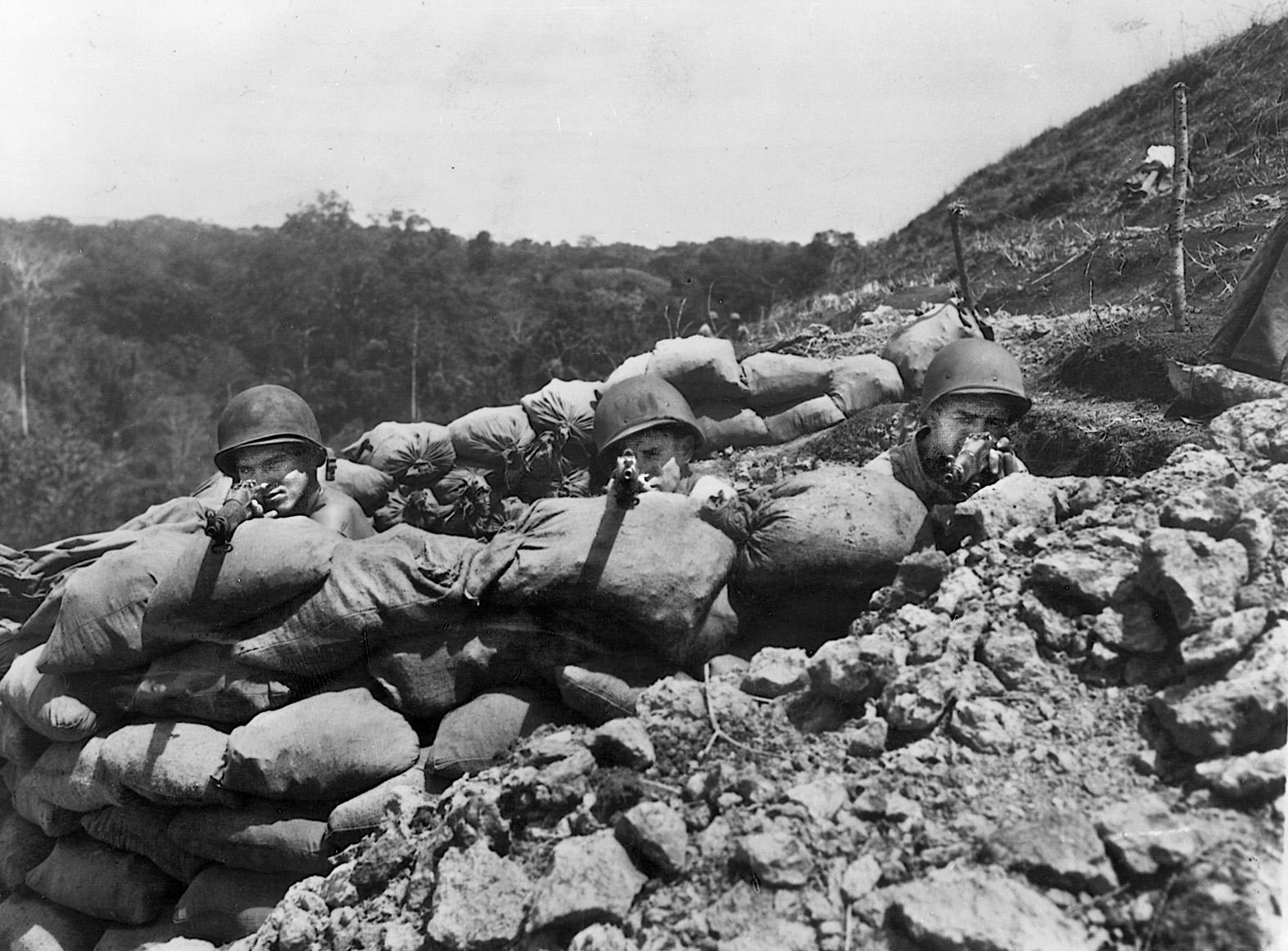

While liaison aircraft, mainly L-5s after the spring of 1944, were used during the Italian campaign, the most extensive use occurred over the battlefields of France, Belgium, and finally Germany. From D-Day to V-E Day, they performed 97 percent of all artillery adjustment missions in the European Theater. These aircraft were also responsible for a high percentage of battlefield observation missions, complemented in part by Army Air Forces reconnaissance planes. Due to the generally open, rolling terrain found in northwestern Europe, aerial observation and artillery spotting was relatively easy. Any German soldier who saw an enemy liaison plane in the sky knew very soon a lethal American artillery barrage would break over his head. This made German movement during daylight hours problematic.

Liaison pilots found that fields and farm roads in theater served well as makeshift landing strips. Even in snowy conditions, which visited Western Europe with a vengeance in the winter of 1944-1945, the little planes could land almost anywhere if fitted with skis.

By the autumn of 1944, the tactical advantage had turned in favor of the Allies, thereby providing additional opportunities for more effective use of liaison aircraft in combat. Better coordination between friendly artillery batteries and spotter aircraft brought increasingly faster response times to fire mission requests from ground commanders. Inclement weather during late 1944 and the beginning of 1945, however, drastically reduced the effectiveness of the liaison planes. The extremely harsh weather grounded all aircraft for lengthy periods of time. Stories abounded of individual L-4 and L-5 pilots braving the elements long enough to fly fire support operations to aid beleaguered American troops, especially during the bitterly fought Battle of the Bulge between December 1944 and January 1945.

During World War II, especially in Europe, liaison planes had to deal with the threat of enemy aircraft. One of the most vociferous arguments between the Army Air Forces raised against the retention of liaison assets by the Army ground forces was the inherent vulnerability of these planes to enemy fighters. The Army Air Forces’ contention in this case was certainly correct: L-4s and L-5s were no match for the swift and deadly German fighters that they might encounter over the skies of northwestern Europe. In addition, the German high command offered what amounted to a bounty on the heads American liaison aircraft. Luftwaffe pilots were awarded various types of air medals and leave points for destroyed liaison planes.

During 1944 and the first part of the following year, a number of L-4s and L-5s were lost to German fighters and ground-based antiaircraft fire as the Allies advanced across France and into the Reich. The liaison pilots were able to use a degree of aerial chicanery against enemy aircraft that improved their chances of survival when they met hostile warplanes. When attacked by enemy fighters, the L-4 and L-5 pilots would dive for the deck and then fly as slowly as possible. This action would force the attackers into a stall. Recovery was almost impossible at the low altitudes the American planes were flying if the latter attempted to intercept the liaison aircraft. Liaison pilots would also try to lure enemy warbirds over the American lines, where the Germans would then have to face U.S. antiaircraft ground fire, as well as roving Yank airplanes. But the best defense against hostile planes was always remembering that discretion was the better part of valor, in other words avoiding air space containing German combat aircraft.

Although most liaison pilots always attempted to sidestep areas where enemy airpower and/or ground fire could hinder their work and even cause their destruction, some intrepid liaison skippers went looking for ways to make life difficult for the Nazis. A vivid case was the action of Major Charles “Bazooka Charlie” Carpenter, chief of the U.S. 4th Armored Division’s reconnaissance aircraft detachment. On September 19, 1944, the opening day of a series of tank battles on the Western Front spanning 11 days and known as the Battle of Arracourt, fought in the Lorraine region of northeastern France and second only to those armored engagements fought during the Battle of the Bulge, Major Carpenter was conducting a routine reconnaissance patrol. Seeing German tanks sneaking around a platoon of American tank destroyers, he put his L-4H into a dive and out of the rain and fog attacked the offending panzers with 2.36-inch bazooka rockets he had fitted to the fuselage of his plane. Although he failed to score any hits on the enemy armored vehicles, his actions were enough to alert his comrades on the ground to the potential danger. The U.S. tank destroyers as a result were able to turn the tables on their would-be attackers and eliminate the advancing enemy armor. Later the same day, Carpenter once more assaulted enemy tanks, diving at an 80-degree angle and pulling up only 1,500 feet from the ground while delivering hits from his missiles on two German tanks, causing their crews to abandon both vehicles.

Another innovative way to use the liaison planes was suggested by none other than Lt. Gen. George S. Patton, Jr. As his Third Army neared Germany’s one-mile-wide Rhine River, the western boundary of the Third Reich, he wanted to use L-4s and L-5s to airlift American troops across that waterway to secure bridgeheads on the east bank of the river. The novel scheme was only put aside when the U.S. First Army in early March was able to capture intact the large Ludendorff railway bridge over the Rhine at Remagen.

As in Europe, liaison aircraft played a significant role in the Pacific, albeit on a smaller scale. The reason for the different level of participation was that, unlike in the European Theater, warfare in the Pacific was based on amphibious landings supported by massive naval and air bombardments, usually against small islands. This often meant that L aircraft were brought onto shore crated and then assembled after the objective was won by the ground forces. Sometimes the planes might not be off-loaded onto land for days after the American landings. As a result, the surveillance craft would be flown off jury-rigged flight decks made of sheets of steel matting placed over the decks of converted Navy LSTs (Landing Ship, Tank) forming a seaborne runway. This practice was first initiated during the Anzio landings on the Italian west coast in late January 1944.

Of course, once in the air the planes were not able to land back on the LSTs. The solution to this fundamental problem led to the introduction of an apparatus vital in the recovery of aircraft flown off these vessels. Named after its inventor, Army Air Force Captain James H. Brodie, the “Brodie Device” was first and only used during the fight for the island of Okinawa in April 1945. The captain’s invention consisted of four masts extended over the water from the deck of an LST and supported by a strong horizontal steel cable. A trolley with an attached sling underneath ran alongside the cable, and in turn the sling caught a hook that was attached to a moving L-4 or L-5. If properly arrested by the sling the plane would stop immediately in midair and then could then be lifted to the deck level of the LST and hoisted aboard. A specially reconfigured LST launched and retrieved a number of liaison craft off its deck during the Okinawa operation without loss of a plane or pilot. As was the case in Europe, the liaison aircraft in the Pacific acquitted themselves with distinction by performing myriad functions, including calling in timely naval gunfire support for U.S. troops conducting amphibious operations.

“L” aircraft, although small, single-engine, slow, and unarmed, added a valuable dimension to both artillery spotting and battlefield observation during World War II. They provided artillery batteries and field commanders with much-needed information about enemy targets, positions, and movements much more rapidly than during the World War I, thus reducing the time required for artillery fire to be delivered against enemy positions. They also served well in capacities such as medical evacuation, command and control, relaying communications, and wire laying. They were easy targets for enemy air and ground fire, but the loss rate among them was minor compared to the 3,500 deployed in the war.

SIDEBAR:

The L-5 Stinson Sentinel was known as the Flying Jeep

The L-5 Stinson Sentinel observation liaison aircraft was the only purpose-built plane of its type manufactured in the United States during World War II. Known as the “Flying Jeep,” it was manufactured by the Stinson Aircraft Company of Wayne, Michigan, later a subsidiary of the Vultee Aircraft Corporation. The L-5 series and its five variants were manufactured between December 1942 and September 1945 for a total of 3,590 built. In terms of light observation aircraft, production numbers for this unarmed two-seater were second only to the Piper L-4 Cub.

The fuselage was constructed using chrome-moly steel tubing covered with doped cotton fabric. The wings and empennage were made of spruce and mahogany plywood box spars and plywood ribs and skins also covered with fabric. The only aluminum, which was in short supply, was on the engine cowling, tail cone, framework for the ailerons, rudder and elevator, and landing gear fairings. The L-5 was powered by a six-cylinder, 190-horsepower Lycoming 0-435-1 piston engine.

The L-5 was introduced into service with the U.S. Army Air Forces in the spring of 1944 and made its debut in the Italian campaign. Soon thereafter it was used by all the branches of the U.S. military as well as the British Royal Air Force. A large number of these craft were purchased by the Army for use as an adjunct of the close air-ground support mission. Faster and more powerful than the L-4 and L-5 liaison planes, the later variants of the L-5 were essentially upgraded and improved versions of those two earlier models. A strong and robust engine allowed the later L-5 to take more effective evasive action against enemy antiaircraft fire and fighters. It was equipped with a powerful radio, which greatly enhanced its air-to-ground and air-to-air communications capability.

Because of its effectiveness, the L-5 was cross-utilized by the Army ground forces and Army Air Forces in Italy. A number of L-5s were flown by Army Air Forces pilots as observers to direct American fighters and fighter bombers, including P-51s and P-47s, on strafing and bombing runs. Conversely, these missions were also flown with Army liaison pilots at the controls and with Army Air Forces pilots acting as observers. These operations in Italy were known as “Horsefly” missions and were quite successful.