By William E. Welsh

Word spread like wildfire through Martinsburg in northeastern Virginia that the Yankees were on the move. On July 2, 1861 Maj. Gen. Robert Patterson led a corps of 25,000 bluecoats south from Williamsport, Maryland, toward the small town, which was defended by Brig. Gen. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson’s 2,300-man Virginia brigade. Jackson had strict orders from superior, General Joseph E. Johnston, to avoid a general engagement with Patterson. To fulfill those orders meant Jackson might have to abandon Martinsburg to the enemy.

Jackson led one regiment north to reconnoiter Patterson’s army and discern his intentions. He found Patterson advancing in force and offering battle. Jackson gathered his brigade and withdrew south of Martinsburg to Darkesville. Two days later Patterson marched into Martinsburg. Some of the boisterous Yankees decided to take out their anger on the people of Martinsburg.

“The doors of our houses were dashed in, our rooms were entered by soldiers who might literally be termed ‘mad drunk,’ wrote 17-year-old Belle Boyd. “They left our homes mere wrecks, utterly despoiled and mutilated. Shots were fired through windows; chairs and tables were hurled into the street.”

One group of Yankees forced their way into the Boyd house on the first day of the occupation with the intention of raising the Stars and Stripes over its roof. Belle’s father was away serving in the 2nd Virginia in Jackson’s brigade.

“Men, every member of my household would die before that flag shall be raised over us,” Belle’s mother told them. When a drunken Yankee took a threatening move forward and loudly cursed both mother and daughter, Belle pulled out a Derringer pistol and shot him. “I could stand it no longer,” she wrote afterward. “My indignation was roused beyond control; my blood was literally boiling in my veins.”

Belle had inflicted a mortal wound on 25-year-old Private Frederick Martin of Company K, 7th Pennsylvania Volunteers. Martin’s friends carried him to a hospital tent where he passed away later in the day. When they threatened to return and burn down the house in retaliation, Belle reported the matter to Patterson. He decided to investigate the matter himself before making a judgment regarding Belle’s fate. After hearing the Boyds’ account, he then interviewed the Union soldiers involved in the incident. Patterson decided that Belle had acted in self-defense. He posted sentries at the house to ensure that there was no further harassment of the family.

Boyd is one of several women who became spies for the Confederacy. In Boyd’s case, her fame and enduring legacy after the war would become intrinsically woven with that of Jackson, for she would play a key role in intelligence gathering during parts of his renowned Valley Campaign of 1862.

Isabella Maria Boyd was born in Martinsburg in 1844 to shopkeeper Benjamin Boyd and Mary Rebecca Glenn. Her parents enrolled her at the age of 12 in Mount Washington Female College 75 miles to the east in Baltimore, Maryland. While at the elite boarding school, she studied literature, foreign languages, music, and etiquette. After completing a four-year course of study, she was introduced into society in Washington, D.C.

Having narrowly escaped arrest for shooting the Federal soldier, Belle proceeded with a relish to gather whatever intelligence she could from Patterson’s army while it was based in Martinsburg. She sought out the company of Northern officers with whom she flirted to loosen their tongues. Many were smitten with her good looks and proved to be easy marks. She wrote down the information, a sign of an amateur spy, and secreted away her notes. By candlelight late in the evening she would draft dispatches, which she called “lettres de cachet,” to be delivered to Jackson’s camp at Darkesville by close friends, family servants, or Belle herself.

Belle was a skilled horsewoman, and on a number of occasions she rode her horse, Fleeter, to deliver the messages. She used a variety of methods to conceal the dispatches; for example, she sewed them into the soles of shoes or stuffed them into loaves of bread.

Her amateur methods and the frequency with which she was communicating with Confederate officers led to the interception of one of her dispatches by Federal troops. One afternoon Captain James Gwyn, an assistant provost marshal, came to the Boyd house and instructed Belle to accompany him to the Berkeley County Courthouse where the Yankees had established their headquarters.

It was a particularly easy case for Federal officers to prove because the message the Yankees intercepted was not in cipher, but in Belle’s own handwriting. The colonel who interrogated her told her that she was in violation of the Articles of War pertaining to espionage and treason. He warned her that she could be put to death for such activities. She was let off with only a reprimand.

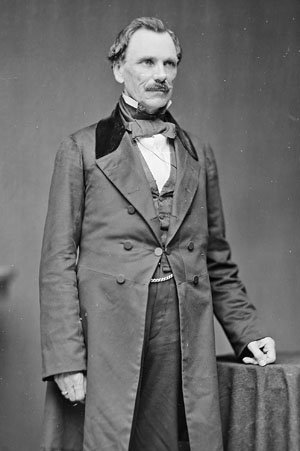

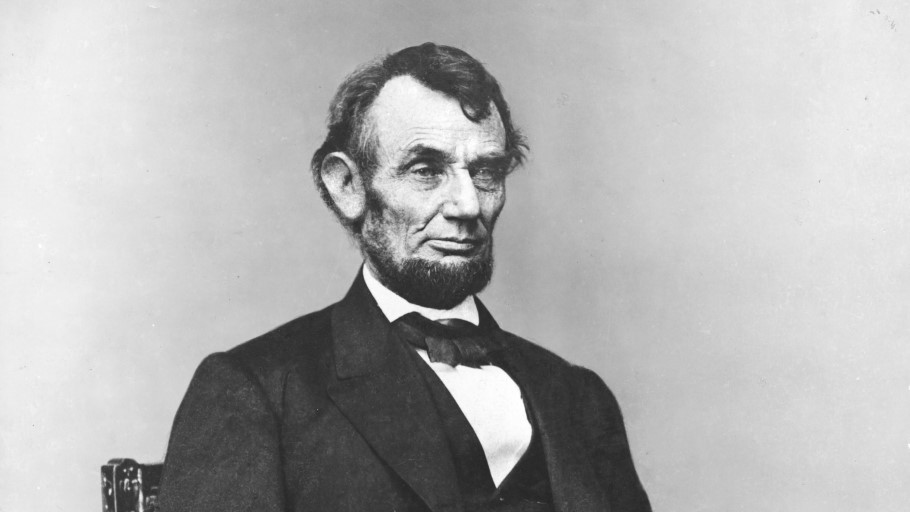

Unbeknownst to Belle, family friend Ward Hill Lamon, who was a bodyguard of Lincoln’, had interceded on her behalf, asking that they treat her with leniency. From that point on, though, the Federals in Martinsburg kept her under constant surveillance.

Jackson’s brigade was part of Brig. Gen. Joseph Johnston’s Army of the Shenandoah. Even before his pivotal role in the Confederate victory at First Manassas, Jackson was regarded as a hero to the people of the Shenandoah Valley for his defense of their homes in the opening months of the war.

Belle and her mother visited Johnston’s camp at Manassas three months after the battle occurred. During the several weeks that Belle was in northern Virginia, she served as a mounted courier, carrying dispatches for Jackson, General P.G.T. Beauregard, and other commanders.

In the winter of 1861 the Federals withdrew again north of her hometown. During this time she became well acquainted with Colonel Turner Ashby, the commander of the 7th Virginia Cavalry, and carried dispatches between Ashby and Jackson, who had made his winter headquarters in Winchester.

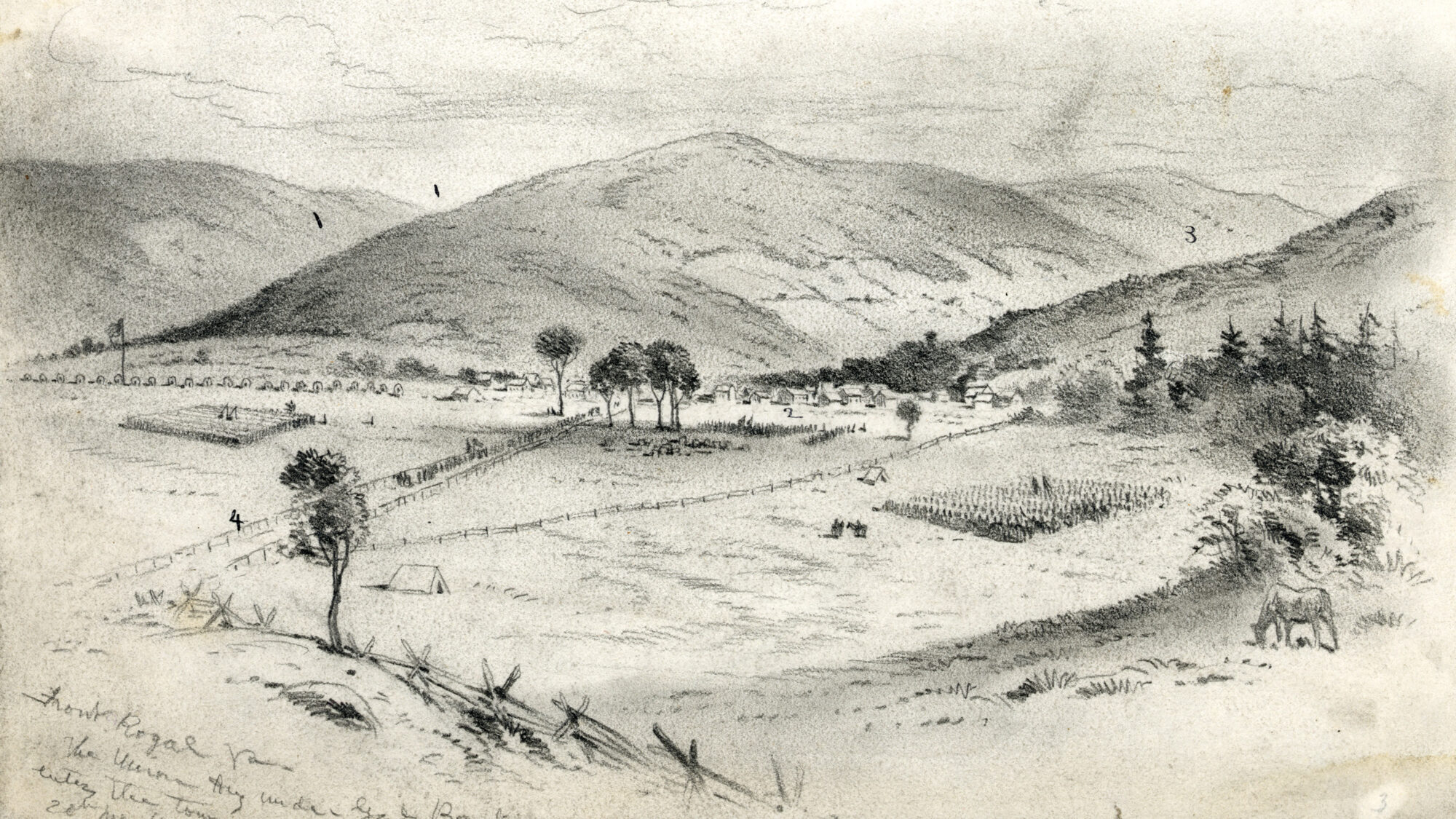

When Belle’s father returned home on furlough he decided to send Belle to live with her uncle and aunt, James and Mary Stewart, at their hotel in Front Royal so that she would be farther from the front lines when the Yankees advanced again. However, the Stewarts departed for Richmond on March 12, leaving Belle behind to live with her maternal grandmother, Ruth Burns Glenn, and cousin Alice. Eleven days later, Brig. Gen. James Shields defeated Jackson at Kernstown on the south side of Winchester, and Jackson retreated 40 miles up the valley to Mount Jackson.

On a journey to Martinsburg to rejoin her mother, Belle was arrested by a Federal provost marshal who had been tipped off that she was a spy. He took her to Baltimore for a hearing before Maj. Gen. John Dix, the commander of the Department of Maryland and Pennsylvania. Dix decided there was not a strong enough case against her and allowed Belle to return home. Having learned of her arrest, Federal authorities in Martinsburg ordered her to remain within the town’s limits.

Shortly afterward, Belle’s mother received permission for her and her daughter to relocate to Front Royal. When they arrived, Belle was delighted to discover that they would be billeted in close proximity to Federal headquarters. Shields and his staff had chosen her uncle’s hotel for their headquarters. Belle and her mother were allowed to stay at a cottage on the property to which her grandmother and cousin had been relocated.

Belle immediately set to work spying on Shields. She eavesdropped on the general’s conferences in the hotel’s parlor by listening through a knothole in the ceiling above it. One morning she heard Shields make an important pronouncement to those assembled. “We march at sunrise,” he said. “Before noon we will attack Jackson in the flank.”

Belle translated what she had heard into cipher. Then she went to the stable, mounted her horse, and rode south. She rode for two hours, covering 15 miles, and pulled up at a house where she knew Colonel Ashby was billeted. Ashby’s jaw dropped when he saw her. “Good God, Miss Belle, is that you?” he asked. After briefing Ashby, they both departed. Ashby rode for Jackson’s headquarters, while Belle returned to Front Royal before sunup.

Shields marched his army south that day, but the Federals did not find Jackson’s force where they thought it was bivouacked. Belle’s efforts had paid off. Meanwhile, a new Federal force entered Front Royal. After her midnight adventure warning Jackson of Shields’ advance, Belle heard of the need for a Confederate courier in Winchester for an important operation.

On May 22 she persuaded a Yankee admirer, Lieutenant Abram Hasbrouck of the 5th New York Cavalry, to assist her in visiting Winchester. He drove them there in a carriage. Belle met with Confederate agent who gave her two satchels and a note for Jackson or another high-ranking Confederate officer. Belle and family servant Eliza began whispering about how they would get the satchels through Union lines. Unbeknown to them, a servant loyal to the Yankees was watching them and informed Federal authorities that the two women were likely planning a clandestine operation.

The two women climbed back in Hasbrouck’s carriage, and he proceeded south on the Valley Pike. When they arrived at the picket outpost on the outskirts of Winchester, two mounted Federal detectives were waiting to question them. “We have orders to arrest you,” one of the detectives said. They escorted the carriage to the headquarters of Colonel George Beal of the 10th Maine Infantry. Belle had tried to disguise one of the packages as a gift from Hasbrouck, and she had written on the exterior “Kindness of Lieutenant Hasbrouck.” Beal demanded that Hasbrouck explain his role in the matter. When Beal tore open the package, he found a copy of the Secessionist journal Maryland News Sheet.Belle tried to get Hasbrouck off the hook but was unsuccessful.

All this time, Belle was holding the secret message to Jackson in her hand. Although Beal demanded she relinquish it, she casually said, “It is nothing, you can have it if you wish.” She held it out for him, but he was so furious with Hasbrouck that he accepted Belle’s explanation without reading the note himself. Belle was dismissed, but Hasbrouck was detained and ultimately cashiered from the Union Army.

When Belle reached Front Royal, she read the dispatch she had carried in her hand. It gave the position of all of the Union forces converging on the Lower Valley in an effort to destroy Jackson’s fast-marching army. As Belle already knew, a detachment under Brig. Gen. John Kenly garrisoned Front Royal. Brig. Gen. Nathanial Banks was in Strasburg, Shields was in Luray, and Brig. Gen. John Fremont was farther west in the Alleghenies. She would have to wait until morning to figure out how to get word to Jackson. It would be difficult because Kenly had imposed martial law and no citizens were allowed to leave the town.

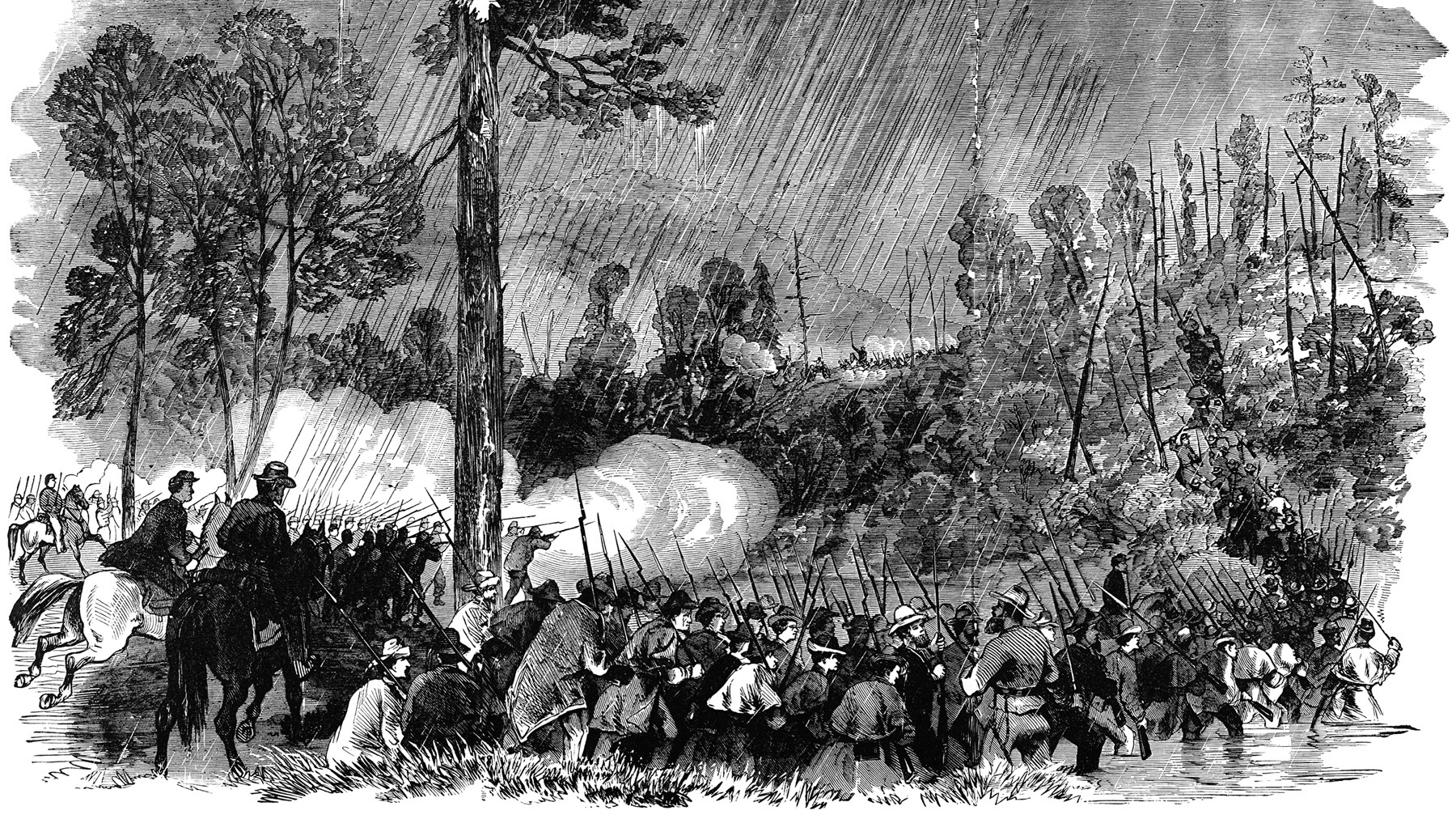

Jackson marched north from Luray with 17,000 men on May 21, and two days later attacked Kenly’s force of 1,000 troops in Front Royal. The Federal camp was situated a half mile north of the town. Union pickets held important crossings over the north and south forks of the Shenandoah River which join at Front Royal. Jackson had every intention of capturing them intact. His troops swept downhill into the town at 2 pm. The Federals were taken completely by surprise.

Belle and the other residents of the town first heard shots ring out from the hillsides and suddenly the street was full of blue-uniformed soldiers rushing every which way. Belle asked a Federal officer what was going on, and he replied that the Rebels were moving in strength against the town. When asked what the Federals planned to do, the officer told her that they would try to get the ordnance and quartermaster supplies out of town to prevent them from falling into enemy hands, but if the Rebels came on too quickly, they would have to burn them.

Belle decided to pass the information she had just gleaned from the officer, as well as what she knew about the strength of Kenly’s garrison, to the approaching Confederates. She ran as fast as possible to the outskirts of town and continued into the fields that lay beyond. She heard bullets whistle past her and realized that the Yankees were firing at her.

When the Confederates came into view, she waved her bonnet in wide arcs. Some of the Rebels recognized her and cheered the gallant lass. “Their shouts of approbation and triumph rang in my ears many years afterward,” she wrote.

Jackson’s acting assistant adjutant, 21-year-old Lieutenant Henry Kyd Douglas, a native of Shepherdstown, Maryland, pointed out the approaching woman to both Jackson and Maj. Gen. Richard Ewell. Ewell told him to find out what the woman wanted. Douglas eagerly rode over to see what the woman was so worked up over. She called out his name, and he instantly recognized her. “I was not much astonished when I saw that the visitor was the well-known Belle Boyd whom I had known since earliest girlhood,” he wrote. “She was just the girl to dare to do this thing.”

She handed the dispatch from the Confederate agent in Winchester to Douglas. “I knew it must be Stonewall when I heard the first gun,” she panted breathless. “Go back quick and tell him that the Yankee force is very small. [It consists of] one regiment of Maryland infantry, several pieces of artillery, and several companies of cavalry…. Tell him to charge right down and he will catch them all.” She then walked back to town.

Jackson rode over to Douglas, who briefed his commander and handed him the dispatch. The Confederates quickly seized the town, and Kenly conducted a rearguard action on the north bank of the North Fork of the Shenandoah River. After a furious artillery duel lasting an hour, Confederate cavalry forded the shallow North Fork in multiple place, making Kenly’s position untenable.

The one-sided battle ended in a resounding victory for Southern arms, and Jackson’s army netted 700 prisoners and captured all of Kenly’s stores. Douglas scouted the streets for Belle and found her talking to a group of Federal prisoners. He handed her a note from Jackson. “I thank you, for myself and the army, for the immense service that you rendered your country today.”

Jackson’s Valley Campaign soon took him south again where he defeated Fremont at Cross Keys on June 8 and Tyler at Port Republic on June 9. When the Federals retook Front Royal, Belle was promptly arrested. The taciturn Union Secretary of War Edwin Stanton had issued instructions for her arrest and transport to Washington, where she was incarcerated at the Old Capital Prison. Her stint in prison did not break her spirit, though. Her sense of humor carried her through the experience.

Federal authorities eventually allowed her to depart for Richmond where she arrived to a hero’s welcome. When Lee marched into Pennsylvania in June 1863, Belle took the opportunity to visit Martinsburg, which had returned to Confederate control. When the Federals returned following Lee’s sorrowful retreat from Gettysburg, they placed Belle under house arrest. Stanton decided after a month to arrest her again and confine her in Washington. She was subsequently confined at Carrol Prison, an annex of the Old Capitol Prison.

When she helped three prisoners escape by distracting the guards, Federal authorities grew weary of her tricks. She was formally charged with espionage and sentenced to hard labor at Fort Monroe for the duration of the war. On her way by boat to the fortress, she learned that her sentence had been commuted. She was allowed to take a boat to Richmond.

Belle was so well known by that time that she could no longer perform the services of a spy. She discussed with Confederate President Jefferson Davis how she might assist the South. The Mississippian advised her to serve as a courier running dispatches back and forth to England on blockade runners. The boat she departed on, the Greyhound,was intercepted by a Federal cruiser, Connecticut,and Belle was taken aboard the Federal ship but not confined. One of the officers, Lieutenant Samuel Hardinge, became smitten with her. He subsequently proposed to her, but she declined. The cruiser docked in New York, and Belle quickly became the object of attention in the metropolis. The Northern press referred to her as “Cleopatra of the Secession.”

Hardinge proposed a second time in New York City, and this time Belle accepted. They sailed to Boston, but Federal authorities in that staunchly abolitionist city would not permit Belle to stay. They advised her to go to Canada, but Belle decided to continue on to England as originally planned. Hardinge followed her shortly afterward, and they were wed abroad.

Hardinge was soon discharged from the U.S. Navy for neglect of duty. Under Belle’s influence, he agreed to carry dispatches for the Confederate government aboard vessels bound for the Eastern Seaboard. He was caught, arrested, and imprisoned. To raise funds for herself and her imprisoned husband, Belle wrote her memoirs, which were published in England. At the same time, she embarked on an acting career. Hardinge’s health failed, and he died in prison.

Belle eventually returned home where she began speaking tours. She married two more times. Her second husband was an English officer, and her third was an actor from Ohio. While on the tour circuit she died on June 11, 1900, of a heart attack in Kilbourn, Wisconsin. She was buried on Northern soil, where she perished.

Belle frequently embellished her achievements, and some are undoubtedly fabricated, particularly in the absence of corroborating accounts. Her accomplishments did little for the South as a whole, although they might have had some local effect in regard to what occurred in the Lower Shenandoah Valley. Her zealous nature speaks volumes about the spirit of Southerners who were willing to endure hardship for their beliefs.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments