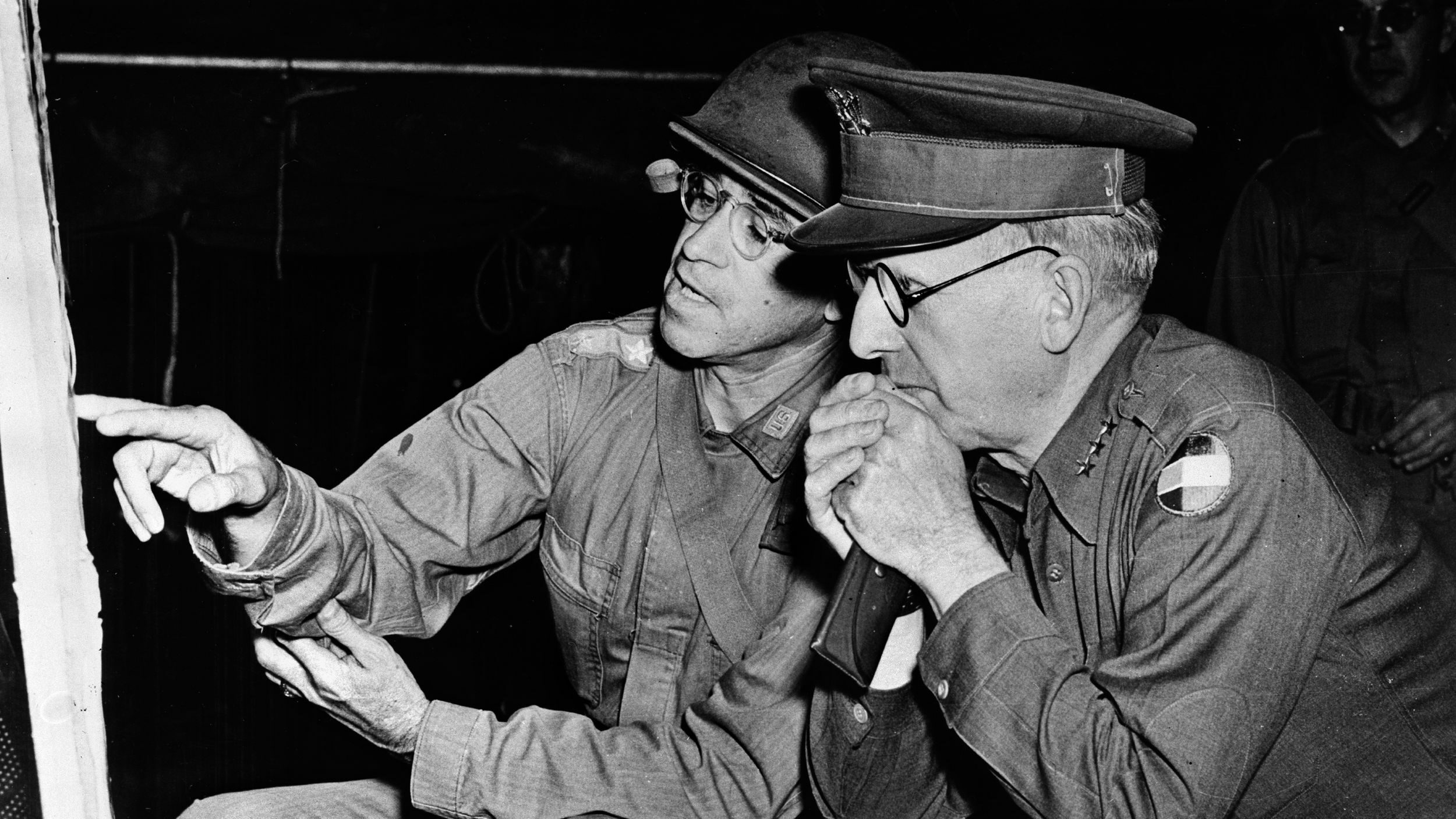

Although the rattle of musketry that signaled the beginning of the Confederate attack commenced at 5:00 a.m., on the morning of April 6, 1862, Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant did not arrive at Pittsburgh Landing for five long hours. This was because the commander of the Army of the Tennesee was at his headquarters in Savannah, about nine miles away downriver. Having just finished breakfast, he was just about to drink a cup of coffee when he heard the steady rumble of artillery in the direction of Pittsburg Landing. “Gentlemen, the ball is in motion,” he said to his staff. “Let’s be off.”

Shortly thereafter the general, staff, orderlies, clerks, and horses were aboard the steamship Tigress and on their way to Pittsburg landing. When he arrived, Grant was pleased to see that the majority of his troops were fighting hard under tremendous pressure from wave after wave of rebels. A few thousand, mostly the raw recruits who had never seen a gun fired in anger, huddled beneath the bluffs near the landing for safety, but the rest were performing prodigies of valor.

Shortly thereafter the general, staff, orderlies, clerks, and horses were aboard the steamship Tigress and on their way to Pittsburg landing. When he arrived, Grant was pleased to see that the majority of his troops were fighting hard under tremendous pressure from wave after wave of rebels. A few thousand, mostly the raw recruits who had never seen a gun fired in anger, huddled beneath the bluffs near the landing for safety, but the rest were performing prodigies of valor.

Although suffering from a leg injury that forced him to walk with a crutch, Grant was hoisted into the saddle. His injury was so bad it could have given him an excuse to stay at the landing in relative safety.

Several Union officers provided exemplary leadership that bloody day, but the real rock of Shiloh was Grant himself. He seemed not only one person but several, appearing as if by magic were the fighting was the heaviest. Minie bullets whistled through the air like swarms of angry bees, but he paid them no heed, calmly issuing orders as if the occasion was a peacetime review. He radiated confidence, exuded it from every pore, and his straightforward, positive demeanor gave fresh heart to his men.

At one point a courier, having just delivered a message, had his head blown off moments later. Grant was sprayed by the man’s blood, but the general was unfazed and showed no emotion. “Not beaten yet by a damn sight,” he mumbled.”

The challenge that Grant faced at Shiloh, which became a critical turning point in the American Civil War, was a formidable one, explains regular contributor Eric Niderost in his thought-provoking article “Grant’s Ordeal at Shiloh” in the March 2019 Military Heritage. Although some of his subordinate commanders turned in fine performances, Grant was a rock at Shiloh steadying his troops’ nerves as they fought like demons to stem the Confederate onslaught. The steps that Grant took on the first day laid the foundation for his successful counterattack on the second day after the arrival of Maj. Gen. Don Carlos Buell’s Army of the Ohio.

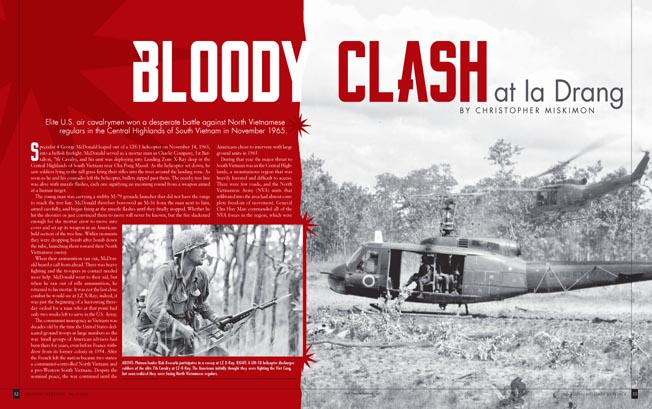

The issue also contains a compelling article by frequent contributor Chris Miskimon on the seminal battle of the Vietnam War fought in Ia Drang Valley in November 1965. The article pitted Lt. Col. Harold Moore’s reinforced 1st Battalion, 7th Cavalry against North Vietnamese regulars in the Central Highlands of South Vietnam. The bloody clash exhibited the 1st Air Cavalry Division’s mobility and firepower; after the battle, the North Vietnamese never again willingly engaged the division in head-to-head combat.

Another frequent contributor, Alexander Zakrzewski, writes a stellar account of the medieval Crusade of Varna in 1444 that pitted a formidable Polish-Hungarian army co-commanded by the young King Ladislas who held crowns of both kingdoms and veteran Hungarian warlord John Hunyadi. Varna was one of the so-called later crusades in which the Europeans sought to check the expansion of Ottoman Sultanate into Europe. After an auspicious march into Ottoman-held Bulgaria, the crusaders found themselves trapped with their backs to the Black Sea by Ottoman Sultan Murad II’s powerful Ottoman army. The battle hinged on whether Hunyadi could not only parry the thrusts of the attacking Ottoman troops, but also prevent Ladislas from making any major blunders as a result of his inexperience. Zakrzewski, who has a knack for relating the action in a gripping manner, recounts the crusaders’ valor on that fateful November day.

Long-time contributor Robert Heege contributes an article to the issue on the Second Battle of Custoza in 1866 that was part of Third Italian War of Independence. When the Austrians found themselves engaged in a life or death struggle with Prussia during the Austro-Prussian War, the Italians sought to take advantage of the situation by attacking Venetia with the hope of consolidating it into a unified Italy. The Italians miscalculated the Austrians’ resolve, though, for they immediately marched to the aid of the Venetians. The two sides clashed on the hilltops surrounding Villafranca in a swirling battle. It quickly became apparent that the Italians were outclassed by the veteran Austrians.

In the opening phase of the battle, a group of Austrian uhlans charged elements of the Italian III Corps. “The appearance of the dreaded uhlans coming on like a horde of bloodthirsty mounted devils gave rise to a general disorder in the ranks of the III Corps,” writes Heege. “Whole groups of [General Giuseppe] Govone’s men were being ridden down like dogs in the olive gardens of Villafranca, lanced front and back in their desperate attempts to escape impalement.”

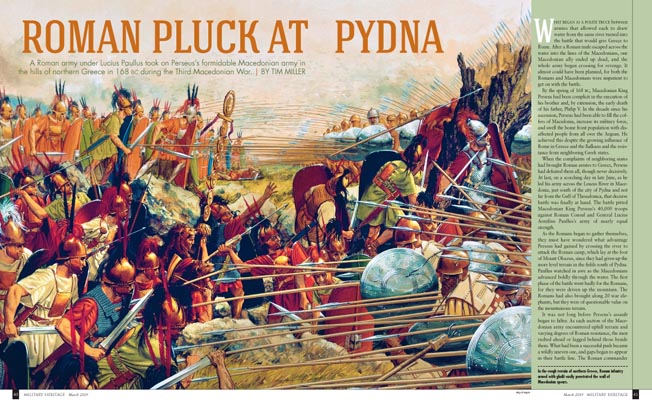

Contributor Tim Miller, whose expertise lies in Ancient Warfare, writes about the decisive engagement between the Macedonians and Romans at Pydna during the Third Macedonian War. The battle came at a time when the Roman Republic was coming to grips with the realization that it had no choice but to become embroiled in foreign wars in order to maintain its position as a dominant power in the Mediterranean world. The battle was significant because the Romans, armed with their short swords, were much better at fighting in isolated groups and in rough terrain than the Macedonians with their unwieldy spears organized in tightly packed phalanxes.

Contributor Tim Miller, whose expertise lies in Ancient Warfare, writes about the decisive engagement between the Macedonians and Romans at Pydna during the Third Macedonian War. The battle came at a time when the Roman Republic was coming to grips with the realization that it had no choice but to become embroiled in foreign wars in order to maintain its position as a dominant power in the Mediterranean world. The battle was significant because the Romans, armed with their short swords, were much better at fighting in isolated groups and in rough terrain than the Macedonians with their unwieldy spears organized in tightly packed phalanxes.

Editor William E. Welsh contributes an article on Hungarian King Matthias Corvinus whose Black Army was one of the few standing armies in medieval times. The success of the Black Army stemmed from the ability of the component arms to work seamlessly with each other. It enabled Matthias to conquer Silesia, Moravia, Lusatia, Lower Austria, and Styria, as well as hold back the Ottoman tide.

Frequent contributor William F. Floyd Jr. chronicles the development and deployment of the CSS H.L. Hunley, which sunk the USS Housatonic in Charleston Harbor in February 1863. Although the first American underwater vessel to sink an enemy warship, more Confederate lives were lost in the development and testing of the submarine than in its sole attack against Union blockading ships.

Long-time contributor Blaine Taylor recounts how Italian Marshal Rodolfo Graziani, who perpetrated heinous war crimes in Ethiopia, escaped post-war justice. Graziani was responsible for perpetrating the Yekatit 12 massacre in Addis Ababa. The massacre came in the wake of attempts by a pair of Ethiopians to assassinate Graziani and other Italian officials at a public event on the steps of the royal palace. Taylor recounts the events and explores the shortcomings of post-war justice in relation to fascist Italy.

Look for the latest issue of Military Heritage at bookstores and newsstands, or order a subscription HERE so you don’t miss an issue. You can also call our toll free number: 800-219-1187.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments