By Don Hollway

In July 1637 few Scots or English would have guessed the result when Edinburgh minister James Hannay preached from the Book of Common Prayer, and street merchant Jenny Geddes threw her footstool at his head. “Devil give you colic in your stomach, false thief,” said she, “dare you say the Mass in my ear?”

The Book, mandated by King Charles I, was a liturgy of the Anglican Church, which to Presbyterian Scots was tantamount to Catholicism. Geddes’ outburst became a riot, then rebellion, then the Wars of Three Kingdoms, also known as the British Civil Wars. For 12 years Royalists and Parliamentarians, Catholics and Protestants battled across Scotland, Ireland, and England. By the time Charles’s head finally tumbled from the chopping block in January 1649, Scotland had decided it preferred a king to an English Commonwealth after all.

Politics in Scotland, as in all of 17th-century Europe, was inextricably tangled with religion. In early 1650 the Covenanters, the political wing of the Church of Scotland, the Kirk, defeated a Royalist invasion sent by Charles II, but when he offered to convert all of Great Britain to Presbyterianism, welcomed him. Neither side, however, bargained in good faith.

The Scottish turnabout was no surprise to the new English government, also divided into squabbling religious and political factions. Many Englishmen were horrified that the Parliamentarian cause had led to regicide. Commander-in-chief Lord General Sir Thomas “Black Tom” Fairfax resigned rather than fight his Scottish former allies. Not so his lieutenant-general of cavalry, Oliver Cromwell, who had transformed England’s motley militias into the professional New Model Army, made it into the most powerful political force in England, and had no qualms about using it against kings and dissenters alike. In the summer of 1650 he was fresh back from overseeing the subjugation of Ireland, including the massacre of thousands of Irish Catholics and English Royalists at Drogheda.

“I believe we put to the sword the whole number of the defendants,” he said. “I do not think thirty of the whole number escaped with their lives. Those that did are in safe custody for the Barbadoes [in servitude].” He accepted Fairfax’s command as Lord General of the Commonwealth army, and few in Parliament were sorry to see him off to fight a war with Scotland on Scottish soil.

With a naval support fleet paralleling their advance, 16,000 troops marched to the adulation of crowds along the way. The ranks included red-coated musketeers with shouldered matchlocks, pikemen in buff leather coats with 16-foot two-handed spears, and mounted cuirassiers in steel breastplates with wheellock pistols and carbines. In Northampton Maj. Gen. John Lambert, who together with Cromwell had defeated the numerically superior Scots in 1648 at Preston, remarked he “was glad to see we had the nation on our side.”

“Do not trust to that, for these very persons would shout as much if you and I were going to be hanged,” replied Cromwell, the regicide.

The political twists that had raised Cromwell and Lambert to command rather than the noose also had them facing a former compatriot: Scottish Lt. Gen. David Leslie. In July 1644 the three had fought together to defeat the Royalists at Marston Moor. But Leslie had something else, something more sinister, in common with Cromwell. At Philiphaugh in September 1645, Leslie had overseen the massacre of 100 Royalist and Irish prisoners and 300 camp followers. It was no fluke. A year later, he pursued 300 Royalists into Dunaverty Castle in western Scotland. The defenders asked for quarter, which Leslie granted, but after they came out of the castle, they were put to the sword, recalled a witness. To this day the ruin of Dunaverty Castle is known as Blood Rock. In 1648, Leslie had refused to support Charles I because the Kirk opposed him; in 1650, with the church backing Charles II, he had accepted command. The Scottish army, though twice the size of Cromwell’s, was mostly raw recruits and rife with dissent. Some of the more hardline Covenanters like Colonel Archibald Strachan and Archibald Johnston, Lord Warriston, still opposed the agreement with Charles.

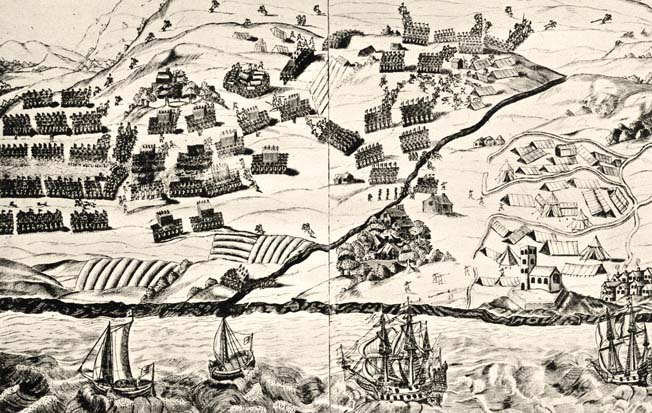

In mid-July the English crossed the border at Berwick-upon-Tweed and at the end of the month reached Dunbar. A small village sited around the ruins of a Norman castle, Dunbar had been the site of a Scottish defeat by the English in 1296, when Edward I of England had conquered Scotland and taken the Stone of Scone, on which Scottish kings were traditionally crowned, home as a trophy. “The streets were full of Scotch women, pitiful sorry creatures, clothed in white flannel, in a very homely manner,” wrote one English officer. “Very many of them much bemoaned their husbands, who, they said, were enforced by the lairds of the towns to gang to the muster [pressed into service]. All the men in this town, as in other places of this day’s march, were fled; and not any to be seen above seven, or under seventy years old, but only some few decrepit ones.”

From Dunbar the road turned west along the Firth of Forth, past the town of Musselburgh toward Edinburgh. Cromwell ordered Lambert to ride ahead with 1,400 horsemen to reconnoiter the capital while he brought up the rest of the army. Lambert found the Scots “entrenched by a line [flanked] from Edinburgh to [the port of] Leith, the guns also from Leith scouring most part of the line so that they lay very strong.”

“When we came upon the place, we resolved to get our cannons as near them as we could; hoping thereby to annoy them,” reported Cromwell. The Scots had manned the ruins of the Iron Age hill forts atop Arthur’s Seat, an 800-foot extinct volcano a mile south of Edinburgh Castle. English musketeers under former Royalist Colonel George Monck stormed the hill and rolled two guns up to lay fire on the Scots, while offshore English men-o-war bombarded Leith. Lambert’s cavalry, however, was repelled before the Scottish lines, and Highlanders under Colonel Sir James Campbell of Lawers retook Arthur’s Seat. In the end Cromwell conceded he could not break in, and as the Scots would not come out, there was nothing to do but withdraw: “Upon the whole, we did find that their Army [was] not easily to be attempted.”

As evening fell the Scottish weather descended. Lacking tents, the English bivouacked out in the open, their woolen jackets and leather buff coats sodden, muskets and armor gathering rust. “In the morning, the ground being very wet, and our provisions scarce, we resolved to draw back to our quarters at Musselburgh, there to refresh and revictual,” wrote Cromwell.

Troops at the head of the march were a bit too anxious to get out of the wet and outpaced those at the rear. The Scots, unwilling to take on the entire English army, saw a chance to destroy its trailing half. Their cavalry, who preferred the lance over the pistol and sword, surrounded Cromwell’s rear guard. English horsemen rode to the rescue and were set upon in turn by Scottish reinforcements, which were then attacked by English infantry. In the snowballing melee Lambert’s horse was killed under him and he was captured. “Worthy Lambert got two wounds, one with a lance into the thigh, the other into the arm with a tuck [sword],” recalled Captain John Hodgson of the General’s Regiment of Foot. A final English attack rescued Lambert and repulsed the enemy. “The Scots were all skulked into their dens and we marched, with empty stomachs, peaceably to our quarters about Musselburgh,” Hodgson wrote.

But the Scots were not through yet. Strachan knew Musselburgh, his hometown, well. And though Maj. Gen. Sir Robert Montgomery hated Royalists, he was not above sending two of Charles’s cavaliers, under pouring rain at 3 AM on July 31, riding up to an English outpost. They claimed to be a returning patrol but actually fronted a brigade of Scottish horsemen. With the sentries deceived and the outpost taken, the Scots charged into Musselburgh. They drove off the English cavalry, but the tumult woke Lambert’s infantry. “We were all roused up, having little to do but to shake ourselves,” remembered Hodgson. “There were 1,500 horse, that were resolved to sacrifice us that morning.”

In a confusion of darkness, rain, muzzle flashes, and clashing steel, the Scots were repulsed. “God appeared wonderfully for us that morning in delivering us, and in destroying our enemies,” wrote Hodgson. “There were about forty of them killed about us, it was judged a hundred in all; and about two hundred taken prisoners, with their horses: we had eighteen or twenty wounded.”

Cromwell wrote Parliament, “Indeed this is a sweet beginning of your business, or rather the Lord’s; and I believe is not very satisfactory to the Enemy, especially to the Kirk party.”

The Covenanters, ascribing failure to treachery in the ranks, decided to purge more than 3,000 suspected Royalists from an army fighting for the Royalist cause. These veterans were replaced with, as one observer noted, “ministers’ sons, clerks and other such sanctified creatures, who hardly ever saw of heard of any sword but that of the spirit.”

“They are not so of a peace as they were, but their disaffection about the King and other divisions increase,” reported an English colonel. “They see themselves in a snare, and would gladly many of them get out. We are assured their honest men will not long hold in with them.”

“I beseech you, in the bowels of Christ, think it possible you may be mistaken,” Cromwell wrote the Covenanters about their bargain with Charles. He sent old comrade Leslie an invitation to parley. The commanders, escorted by about 100 troops each, met on the sandy shore east of Leith. Cromwell inquired of the Scots why they were fighting for a king they mistrusted and encouraged them to defect. “Strachan … being asked seriously by one what he thought of their King … replied that he thought him as wicked as ever, and designing both their and our destruction, and that of the two, he thought his [Charless’] hatred towards them [the Scots] was the more implacable,” learned an English officer.

“Much was said to convince each other, but it amounted to nothing,” stated an English report. To apply pressure, Cromwell marched to encircle Edinburgh. Leslie, as hoped, brought out the Army of the Covenant to block him. What at first appeared to be an invitation to battle turned out, on closer examination, to be an invitation to become mired in a Scottish bog. Instead the two armies spent the day cannonading each other, to little effect; their brigade formations, wide but shallow, allowed passage of cannonballs with minimal casualties.

“We drew up our cannon, and did that day discharge two or three hundred great shot upon them,” reported Cromwell. “A considerable number they likewise returned to us: and this was all that passed from each to other.”

With the weather now taking a toll on the troops, the English decided to withdraw again to Dunbar, the only good harbor between Berwick and Leith. At that location sick men could be put aboard ship, provisions landed, and the Scots, perhaps, enticed to attack. Messenger Richard Cadwell disembarked that day to join the army at Musselburgh. “On Sunday morning the Drums beat, and our army marched to Dunbar, the enemy with their whole army pressing close to the rear of ours within a mile, and sometimes within half a mile of ours,” he later reported. “Their army consisted of eighteen regiments of foot, which together with horse made as (themselves say) 27,000, our army being but 12,000.”

Whenever the English drew up for battle, the Scots backed off; whenever the English withdrew east, “a poor, shattered, hungry, discouraged army,” as Hodgson recalled, the Scots were there to harass them. An English colonel wrote, “Thus from time to time they avoided fighting, neither is it possible, as long as they are thus minded, to engage them; so that to follow them up and down is but to lose time and weaken ourselves.”

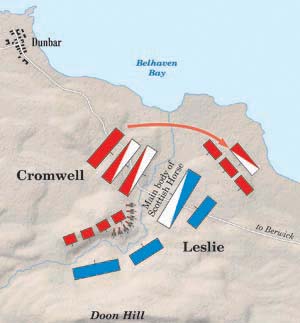

Leslie had fought a masterful campaign, letting weather and disease whittle down the English without ever risking his army. He sent a brigade ahead to cut the English off from retreat to Berwick, and on September 1 occupied Doon Hill, a 500-foot ridge south of Dunbar. As a result, Cromwell’s army was trapped.

“Cromwell was then in great distress, and looked on himself as undone,” wrote Covenanter Lord Warriston’s nephew Gilbert Burnet, then seven years old but later a famed bishop and historian. “There was no marching towards Berwick … nor could he come back into the country without being separated from his ships and starving his army. The least evil seemed to be to kill his horses, and put his army on board, and sail back to Newcastle; which, in the disposition that England was in at that time, would have been all their destruction, for it would have occasioned a universal insurrection for the king.”

“We are upon an Engagement very difficult,” admitted the Lord General in a September 2 letter to the governor of Newcastle. “The enemy hath blocked up our way … and our lying here daily [consumed] our men, who fall sick beyond imagination.” At that point in the year, no new invasion could have been mounted until the next summer, by which time Charles might well lead a Scottish army south.

However, the crest of Doon Hill was not so ideal a position as it appeared. The miserable weather now worked for the English, down in the town and on the plain, and against the Scots on the windswept hilltop. What is more, there was another ill wind blowing on Leslie, from his overseers in the Kirk.

“Leslie was in the chief command, but he had a committee of the states with him to give him his orders, among whom [Burnet’s uncle Lord] Warriston was one,” wrote Burnet. “These were weary of lying in the fields, and thought that Leslie made not haste enough to destroy those sectaries.”

By all accounts Leslie tried to persuade these armchair generals otherwise. “He told them, by lying there all was sure, but that by engaging into action with gallant and desperate men all might be lost, yet they still called on him to fall on,” recalled Burnet.

And so, “Monday morning, before Sun-rising, the Enemy drew down part of their Army toward the Foot of the Hill, toward our Army,” stated an English report. Between the two forces ran the Broxburn, a gully “40 or 50 foot wide, and near as deep, with a rill of water in the bottom, which would be a very great disadvantage to that party who should first attempt to pass it,” described an English pamphlet.

Swollen with rain, the gully ran northeast onto the flatter ground near the coast, where it was crossed by the Berwick road. There stood Broxmouth House, an estate belonging to Robert Ker, 1st Earl of Roxburgh, a Royalist who had fallen out of Covenanter favor and died the previous January.

On the off chance that the Scots were inept enough to assault across the Broxburn, Cromwell brought the English out from Dunbar and arrayed them along the north bank, ordering two dozen of Colonel Thomas Pride’s infantry and a half-dozen of Lt. Gen. Charles Fleetwood’s horsemen to hold the nearest crossing. “The Enemy sent down two troops of Lanciers, who caused our six Horse to return,” stated an English report. “Those [lancers] killed three of our Foot, took three prisoners, and wounded most part of the Rest.”

“Among the three taken by them, there was one stout man who hath but one hand, yet he had thrice discharged his musket before he was taken,” stated an English report. “The Prisoners being brought to David Leslie, he asked the soldier with one hand whether our Army did intend to fight. He answered with the confidence of a Soldier by a question, ‘What did he think they came for but to fight?’ The Scots’ General asked again, ‘how they could fight when they had shipped away half their men, and all their guns?’ The Soldier told him, that if he pleased to draw out his Army, he would find that we had both men and Guns enough to fight him.”

Cadwell later told Parliament, “A most dogged handfast man, this with the wooden arm, and iron hook on it! One of the Officers asked, ‘How he durst answer the General so saucily?’ He said, ‘I only answer the question put to me!’ Lesley sent him across, free again, by a trumpet: he made his way to Cromwell; reported what had passed, and added doggedly, ‘He for one had lost twenty shillings by the business, plundered from him in this action. The Lord General gave him thereupon two pieces, which I think are forty shillings; and sent him away rejoicing.’”

Whether due to his churchmen’s goading or the English musketeers’ taunts, Leslie resolved to give up the high ground. Down at Broxmouth House, recorded Burnet, Cromwell and his officers “walked in the earl of Roxburgh’s gardens, which lie under the hill: and by perspective glasses they discerned a great motion in the Scottish camp: upon which Cromwell said, God is delivering them into our hands, they are coming down to us.”

And more than that: descending the gentler eastern end of the ridge, the Scots proceeded to tuck themselves back to the west, under its steepest slope. “Observing this posture, I told him [Lambert], I thought it did give us an opportunity and advantage to attempt upon the enemy, to which he immediately replied that he had thought to have said the same thing to me,” wrote Cromwell.

Leslie had effectively stashed half his army between Doon Hill and the Broxburn ravine and put the other half near the crossing, where the English could get at it. “It could be no less than a mile of ground betwixt their right wing, near Roxburgh house, and their left wing: they had a great mountain behind them, which was prejudicial, as God ordered it,” wrote Hodgson. The cavalry brigades of Montgomery and Strachan straddled the Berwick road. An attack on that flank would not only open up a line of retreat for the English, but effectively turn the battlefield 90 degrees. The Scottish left would suddenly be a mile to their rear.

“It pleased the Lord to set this apprehension upon both of our hearts, at the same instant,” recalled Cromwell. “We called for Col. Monke [sic] and showed him the thing.”

Monck is said to have replied, “Sir, the Scots have numbers and the hills; these are their advantages. We have discipline and despair, two things that will make soldiers fight: these are ours. My advice, therefore, is to attack them immediately, which if you follow, I am ready to command the [vanguard].”

Some of the lesser officers were for boarding the Navy ships and sailing home, but Hodgson recalled, “Honest Lambert was against them in all that matter…. One steps up, and desires that [General] Lambert might have the conduct of the army that morning, which was granted by the General freely.” Though Fleetwood was nominally second in command and would go on to marry Cromwell’s daughter, he had avoided the trial of Charles I and was more politician than general. With Lambert leading, the English agreed to attack at dawn.

In the Scots’ camp the politicians agreed to stand down for the night. Maj. Gen. James Holborne, who just two years earlier had escorted Cromwell into Edinburgh, gave permission for the musketeers to extinguish their slow match, except for two cords per company. The infantry used fresh-cut corn shocks to fashion makeshift shelter from the rain. The cavalry unsaddled their horses and set them to forage. Many of the commanding officers left their units to get out of the vile weather.

On the far side of the ravine there was little rest that night. Under cover of the rain and clouds, leaving a skeleton force along the ravine, Cromwell’s army pulled up stakes and moved left.

Never in history had an English army made such a maneuver at night and so close to the enemy. A servant remembered how Cromwell “rid all the night before through the several regiments by torchlight, upon a little Scots nag, biting his lip till the blood ran down his chin without his perceiving it, his thoughts being busily employed to be ready for the action now at hand.”

Lambert positioned the English cannon inside a curve of the Broxburn, a salient in the center of the lines from which they could reach all along the Scottish ranks. He ordered his own cavalry regiment and that of Colonel Edward Whalley, Cromwell’s cousin and fellow regicide, to join Fleetwood’s regiment in the forefront, which numbered 1,500 men. Colonel Robert Lilburne, an ardent Baptist who had fought with Cromwell and Lambert at Preston, commanded the second 1,500-man brigade of horse. Two thousand of Monck’s infantry brigade took position on their right. The combined brigades layered up on the Berwick road.

About an hour before sunrise, the weather broke. The clouds parted and the moon shone down on the English regiments stacked before the Broxburn crossing.

Scottish pickets raised the alarm. Lambert’s horsemen charged. Some of Montgomery’s cavalry were caught still in their tents; their general was nowhere to be found. The English cuirassiers thundered across the Broxburn, rode up to those Scottish horsemen who managed to mount, and unleashed a barrage of pistol and carbine fire directly into them. The lancers had no defense. Riders and horses alike piled in the wet grass.

This time it was the Scots’ turn. As Lambert’s brigade paused to reload and reform, Strachan ordered his horsemen forward from behind Montgomery’s. The fiery colonel might well have favored the Parliamentarian cause over the Royalist but would not let that keep him from his duty. “Before our foot could come up, the enemy made a gallant resistance, and there was a very hot dispute at swords point between our horse and theirs,” recalled Cromwell. Strachan’s men rode through Montgomery’s shattered brigade and took Lambert’s English cuirassiers by surprise. If long Scottish lances were of little defense against pistols, empty wheellocks and drawn swords were of little defense against lances. The English cavalry fell back, leaving the Scottish flank unturned.

With the cavalry fight drawn, Cromwell turned to his infantry. Monck led his three regiments splashing across the shallow end of the Broxburn to drive between the enemy horse and foot. About 300 yards up the slope awaited 2,000 Scots, the brigade of Lt. Gen. Sir James Lumsden of Innergellie. Lumsden had served in the Swedish army of King Gustavus Adolphus during the Thirty Years’ War, sided with Parliament on his return, and helped save the day at Marston Moor. At Dunbar he had to face many of those same English veterans with a brigade of raw recruits just levied that summer, many of whom had joined the army just three days earlier.

Monck’s brigade formed up on the far side of the gully, musketeers to the fore, and started up the slope. At 100 yards they paused, raised their matchlocks, and fired into the enemy ranks. Dun-coated, blue-bonneted men fell all along the Scottish line, but their musketeers returned fire and now it was redcoats tumbling to the ground. The toll, however, was not as great. Perhaps Lumsden’s men had already shot most of their ammunition. But since they had taken little part in the fighting, it is equally likely that, given the weather, these three-day soldiers had simply allowed their slow match to get wet. Stepping over their fallen, the English closed to 50 yards and fired another salvo. This time the musketeers parted and ran to either side, revealing the massed pikemen behind them. In the 17th century there can have been few sights more terrifying than a forest of pikes being lowered to horizontal, and the pikemen wielding them advancing steadily with their steel points glittering.

As the two brigades came to grips the light improved, revealing pikemen fencing, probing, and stabbing, musketeers swinging their matchlock butts like six-foot clubs, the cross of St. George and the Saltire (St. Andrew’s Cross) flying. Artillerymen found targets and began bombarding them. “The great guns playing on both sides very fast on each other’s main body,” wrote Cadwell. But the Scottish guns, sited behind their center, were masked by their own lines.

The English cannons in the curve of the ravine fired all across the Scottish front. Lumsden’s brigade, almost end-on to the salient, got the worst of it. Cannonballs raked across its length, reaping droves of men with each shot. Lumsden himself was wounded and taken prisoner. For his raw recruits, that was enough. They broke and ran. Monck’s English marched over the fallen, driving the survivors uphill.

But there stood another 2,000 Scots. This was Sir James Campbell of Lawers’ Regiment of Foot. As Highlanders, the Campbells might be suspected of Royalist sympathies, and indeed Sir James Campbell was one of the Scottish officers absent from the field. His regimental commanders, however, were veterans who knew their business. Sir John Haldane, 11th Laird of Gleneagles, had soldiered for the Dutch and been knighted by Charles I, but he was a fervent Covenanter and had run his estate into debt to raise his regiment. Men with that much at stake did not fold at the first push of pike.

The Scots moved to block Monck’s advance. The English, disordered and depleted by the struggle with Lumsden’s regiments, could not withstand the fresh assault of a well-ordered pike brigade. “Our first foot, after they had discharged their duty, (being overpowered with the enemy) received some repulse, which they soon recovered,” wrote Cromwell. Monck’s brigade fell back to the burn to regroup.

With the cavalry attack on his left and infantry attack in the center stalled, Cromwell was at a crisis point. If the Scots came boiling out from his right and brought all their numbers to bear, it was all over. It was still possible to defeat the entire army by defeating half of it, but not by using only half the English army. Cromwell had to go all in, and had saved the most stalwart of his Parliamentarians to decide the battle.

Lilburne had fought with Cromwell and Lambert at Preston, but his regiment of foot had later mutinied over back pay. Though not implicated, Lilburne was reassigned to the cavalry. When Cromwell ordered forward his brigade to aid Lambert in sweeping away Strachan’s horsemen, he had something to prove.

Captain William Packer commanded Cromwell’s personal regiment of horse, the original Ironsides. Another devout Baptist, Packer had recently fallen in with Fifth Monarchists, who believed the civil wars and regicide were signs of the Second Coming. He had been arrested for refusing to obey a Presbyterian superior officer and was free only due to Cromwell’s personal intervention. He owed the Lord General his freedom and was about to pay him back for it.

Together with Lambert’s men, Lilburne’s brigade and Packer’s regiment outnumbered Strachan’s and the remnant of Montgomery’s. But just to make sure, Cromwell had Packer take his regiment around his extreme left, almost down to the sea, and then back around into the Scottish right flank. It was the English battle plan in miniature. While Lilburne and Lambert locked horns with the Scots head on, Packer’s horsemen piled into them from their right. The brigade formation was designed to face an enemy to its front, not to its flank. Strachan’s men had heart, but swords and lances cannot point in two directions at once. “Major Straughan [sic] was in this fight, and charged desperately,” states one account. “Some of the horse charged, especially those commanded by Col. Strachan, who was wounded,” states another account.

With Strachan out of the fight, the Scottish cavalry lost its best leader. “The [English] horse in the mean time did with a great deal of courage and spirit, beat back all oppositions,” wrote Cromwell, “charging through the bodies of the enemy’s horse, and their foot, who were after the first repulse given, made by the Lord of Hosts, as stubble to their swords.”

“It was resolved we should climb the hill to them [the Scots], which accordingly we did, and through the Lord’s strength by a very short dispute put them to an absolute Rout,” wrote Lambert.

The English horse drove the Scottish cavalry back until they broke for Berwick. There was no point in pursuing them, and Lambert recalled his men. To their right, the door lay open to the Scottish flank. Cromwell famously led his men in singing Psalm 117. The psalm came not from the King James version of the Bible, but from the older Geneva Bible. It was a verse rather ironically not included in Cromwell’s Souldiers Pocket Bible.

Next, it was the infantry’s turn. Monck, the ex-Royalist, might be expected to show a lack of enthusiasm in fighting against his king. Not so the men of Cromwell’s reserve brigade of foot, probably the best in the English army, consisting of his own regiment, Lambert’s, and Pride’s. In 1648 Pride’s troops had forcibly ejected those members of Parliament who still favored rapprochement with Charles; later he had sat as judge at the king’s trial. Cromwell’s own regiment of foot was under the command of Lt. Col. “Praying William” Goffe, a radical Puritan married to the daughter of Cromwell’s cousin Whalley, who like them had signed Charles I’s death warrant.

Goffe had been a mere captain five years earlier; five years hence he would be a major general and ultimately rise to such power that he would be considered as Cromwell’s successor. Men such as Pride and Goffe were not just fighting for their country but for their lives. If Charles II gained the throne they would not only lose everything, but be branded criminals as well. When Lawers’ brigade threatened to overrun Monck’s, Cromwell called on them to tip the balance.

“The Lord General’s regiment of foot charged the enemy with much resolution, and were seconded by Colonel Pride’s men, who were even with some of them for their cruel usage to their fellow soldiers the day before,” reports an English account.

Campbell of Lawers’ Highlanders, stout as they were, could not be expected to stand. Yet they did just that. Pride’s brigade rolled into them end-on, English musketeers on the flanks cross-firing inward, down the length of the formation, while English pikemen jabbed and speared to no avail. Haldane’s regiment refused to give ground.

“One of the Scots brigades of foot would not yield, though at push of pike and butt-end of the musket, until a troop of our horse charged from one end to another of them, and so left them to the mercy of the foot,” recalled Hodgson.

Packer’s cavalry, having ridden completely around the east end of the battle, thundered down the length of Lawer’s brigade, firing into them. Haldane and his top officers were all slain. It was the final straw.

“Two regiments stood their ground, and were almost all killed in their ranks,” wrote Burnet, “the rest did run in a most shameful manner: so that both their artillery and baggage, and with these a great many prisoners, were taken, some thousands in all.”

At that moment the sun rose over the North Sea. Cromwell shouted Psalm 68, “Now let God arise, and his enemies shall be scattered,” and as the English formations marched over the former Scots position, laughed, “I profess they run!”

“Then was the Scots’ army all in disorder and running, both right wing and left, and main battle,” Hodgson recalled. “They had routed one another after we had done their work on their right wing; and we, coming up to the top of the hill with the straggling parties that had been engaged, kept them from bodying: and so the foot threw down their arms and fled.”

Victory was complete. Half the Scots army had not even taken part in the battle; the half that had, if not taken prisoner or dead, crowded into them. Trapped between the steep banks of the hill and the gully, the survivors could only flee west, down the bottleneck toward Edinburgh. Cromwell unleashed his horsemen on them.

“The best of the enemy’s horse and foot being broken through and through in less than an hour’s dispute, their whole army being put into confusion, it became a total rout, our men having the chase and execution of them near eight miles,” he wrote. Such a scene of galloping horsemen cutting down terror-stricken, running men would not be seen in Scotland until the aftermath of the Battle of Culloden, almost a century later.

“David Leslie gave out on Monday night amongst their soldiers, that by seven of the clock on Tuesday they would have our army dead or alive, and they had this defeat and rout before eight,” Cadwell told Parliament a few days later.

“I know I get some share of the salt for drawing them so near the enemy, and must suffer in this as many times formerly; though I take God to witness we might as easily beaten them as we did [the Royalists] at Philiphaugh, if the officers had stayed by their own troops and regiments,” Leslie, who escaped to Stirling, admitted of his men two days after the battle.

The Battle of Dunbar lasted only about two hours. Cromwell wrote Parliament that 3,000 Scots were slain and 10,000 taken prisoner, probably an inflated claim; a contemporary Scottish annalist put the number at no more than 900 killed on the field. All their baggage, 30 cannons, and 15,000 arms were captured. Cromwell reported 30 killed, although the English undoubtedly lost more men than that.

“Thus you have the prospect of one of the most signal mercies God hath done for England, and his people this war and now may it please you to give me the leave of a few words,” Cromwell informed Parliament. He went on to make the only slightly veiled point that the Scottish defeat had been the fault of leaders who had no business directing battles. It was meant as an instructive lesson to Parliament.

Cromwell could afford to make threats. Accompanying news of his victory would have been the grim reports of his treatment of enemies. As many as 5,000 Scottish prisoners were sent south on a death march. Food was withheld. Those who fell behind were shot. Only about 1,400 survived, to be shipped as indentured servants to the New World. This conveyed the message that those who opposed Cromwell could not expect mercy.

“Cromwell upon this advanced to Edinburgh, where he was received without any opposition, and the castle, that might have made a long resistance, did capitulate,” wrote Burnet.

With the Kirk Party in disrepute, the Scots put their faith in Charles II, who led an invasion of England. A year to the day after Dunbar, Cromwell caught the Scots at Worcester, destroyed the remnant of their army, and almost captured Charles himself. Though the king narrowly escaped, the Royalist threat to Britain, which by that point included Scotland, was ended. As it turned out, the more immediate menace to Parliamentarian rule was Cromwell himself. He dissolved the government in 1653. The Army Council named him Lord Protector of the united Commonwealth of England, Scotland, and Ireland. In effect, he was dictator. The Protectorate, as it was known, was due in no small part to Cromwell’s first, and most masterful, victory as Lord General at Dunbar.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments