By Mike Phifer

Spread out and turn the horses north to the river,” Quanah Parker shouted to his fellow warriors. It was the late 1860s and Parker was part of a war party that had swooped down on isolated ranches and farms near Gainesville, Texas. They had managed to steal a good number of horses and were headed back to a safe haven known as the Llano Estacado (Staked Plains). Word of the raid had reached troops stationed at Fort Richardson, and they caught up with the war band along the Red River. The cavalrymen opened fire on the Comanches killing their leader. Parker immediately took charge of the desperate situation.

The warriors raced north for the rough terrain along the river. Parker, who was in the rear, urged the warriors on as bullets fired by a pursuing soldier whizzed past him. Swinging down under his galloping horse’s neck, Parker notched an arrow in his bow. Then, taking cover in a clump of bushes, he straightened himself, turned his horse around, and charged toward the soldier firing the bullets.

Both men rode hard for each other. When they closed to within 100 feet, the soldier fired his revolver, nicking Parker’s thigh. Parker let his arrow fly. It struck the soldier in the shoulder, causing him to drop his gun. Slumped in the saddle, the wounded soldier turned his horse around. The duel was over. Parker had won.

Parker still had to get away. He wheeled around under a hail of bullets and galloped toward the river, rejoining the other warriors who were swimming their horses through the brown water. No longer pursued, the Comanches escaped with the captured horses thanks to Parker’s quick thinking and bravery. These attributes were among the many positive traits of a Comanche warrior who eventually became the most famous Comanche chieftain of the Southern Plains.

Parker was born in Elk Valley in the Wichita Mountains in or around 1848. He was the first born of a white captive named Cynthia Ann Parker and Chief Peta Nocona of the Quahadi band. Nine-year-old Cynthia had been kidnapped by Comanches during the Fort Parker raid of May 1836.

The Comanches numbered approximately 30,000 at the beginning of the 19th century and they were organized in a dozen loosely related groups that splintered into as many as 35 different bands with chieftains. Comancheria, as their territory was known, stretched for 240,000 square miles across the Southern Plains, covering parts of the modern-day states of Texas, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Kansas, and Colorado. Growing up in this world were Comanche men were to be hunters and warriors, Parker was taught to ride at an early age and was skilled in the use of a bow, lance, and shield.

In late 1860 Nocona and his family were living in a camp near the Pease River, which served as a supply depot for war parties raiding the Texas settlements. After one particularly vicious raid, a conglomerate force of U.S. Cavalry, Texas Rangers, and civilian volunteers surprised the Comanches as they were breaking camp on December 18. Although most of the Comanches were killed, Cynthia and her Comanche daughter, Prairie Flower, were captured. Nocona purportedly was killed in the raid. Parker and his brother, Pee-nah, escaped and made their way to a Comanche village 75 miles to the west.

Parker later vehemently denied his father was killed during the raid, stating he was hunting at the time. Nocona died several years later, Parker maintained. Cynthia and Prairie Flower were returned to her Parker kin.

Following his father’s death, Parker was introduced into the Nokoni band, but later he returned to the Quahadi band. He frequently participated in raids in which the Comanches stole horses from ranchers and settlers. It was during such raids that he perfected his skills as a warrior.

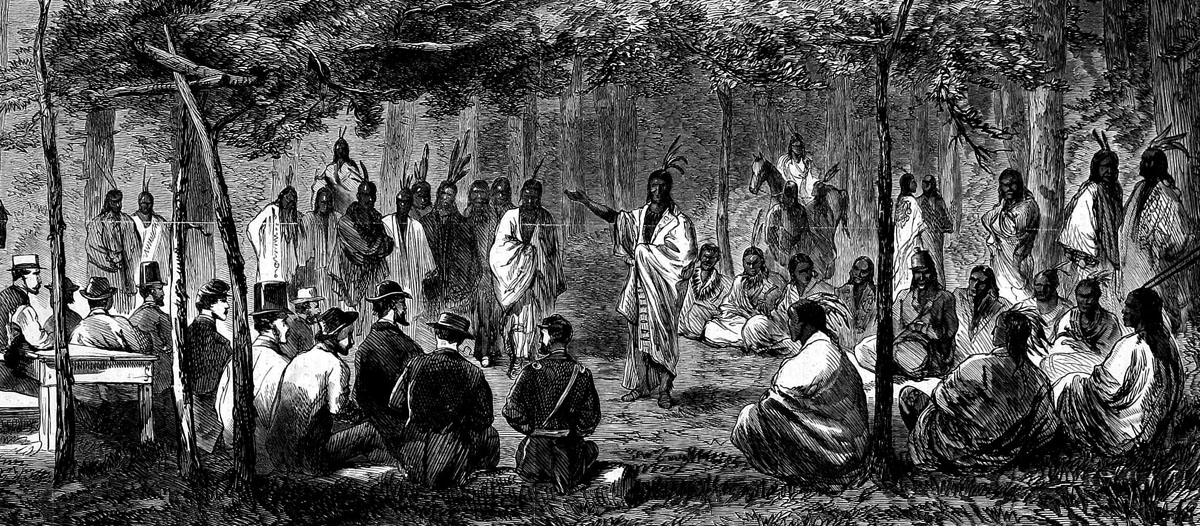

The tribes of the Southern Plains, members of a U.S. government peace commission, and U.S. Army commander General William T. Sherman met in October 1867 at Medicine Lodge Creek, Kansas. The council was attended by upward of 4,000 Kiowa, Cheyenne, Arapaho, Kiowa-Apache, and Comanche. Parker was among the Comanches in attendance. He summarized the talks that led to the Medicine Lodge Treaty as follows: “The soldier chief said, ‘Here are two propositions. You can live on the Arkansas and fight or move down to Wichita Mountains and I will help you.’”

In an effort to end the bloodshed, Sherman and the peace commissioners hoped to move various Southern Plains tribes to reservations, provide them with provisions, and transform them into farmers. On October 21 the various chiefs made their marks on the treaty. About a third of the Comanches refused to sign, among them Parker and the other members of the Quahadi band. Those who agreed to relocate subsequently moved to a 2.9 million-acre reservation in what is now southwestern Oklahoma.

The treaty had little chance of success given that the Southern Plains tribes were nomadic hunters who had no interest in farming. To make matters worse, the U.S. government failed to obtain enough rations and annuities for those who settled on the reservation to survive the first winter. When rations did finally arrive, they were found to be rancid. The warriors believed that the Army had deliberately deceived them.

The so-called non-reservation Comanches came to find a good use for the reservation. They spent the lean winter on the reservation in order to obtain government rations, but when springtime arrived, they returned to buffalo hunting and raiding.

A die-hard non-reservation Comanche, Parker continued raiding in Texas. In the summer of 1869 he participated in a raid deep into southern Texas in which approximately 60 Comanche warriors stole horses from a cowboy camp near San Angelo and then continued to San Antonio where they killed a white man. In response 30 whites set out in pursuit of the raiders.

Catching up with the Comanches, the Texans’ superior rifles allowed them to get the upper hand in the small battle. The Comanches began to fall back, except for Parker, who hid in a clump of bushes. When a couple of Texans rode by him, he emerged and killed both of the men with his lance. Inspired by Parker’s bravery, the other Comanches charged their pursuers. The Texans quickly went to ground. The battle raged until the Comanches ran out of ammunition and withdrew. In appreciation of his valor, the members of the war party elected Parker as their leader. Parker soon began leading raids in Texas, northern Mexico, and other locations.

One Comanche ambush narrowly missed Sherman, who was touring U.S. Army forts in Texas and the Indian Territory in the spring of 1871. The May 18 ambush, known as the Salt Creek Massacre, resulted in the death and mutilation of seven wagoners who were part of a wagon train bearing food for Fort Griffin in north-central Texas. In the wake of the widely publicized massacre, the U.S. government resolved to force the remaining Comanches to submit to reservation life.

Sherman turned to Colonel Ranald Mackenzie, the battle-hardened leader of the 4th U.S. Cavalry based at Fort Richardson, Texas, to cripple the Comanches’ capacity to wage war. In late September 1871, Mackenzie set out with 600 troops of the 4th Cavalry and 11th Infantry, as well as the 25 Tonkawa scouts, to punish the Quahadis. The Quahadis used the Staked Plains, an escarpment in west Texas, as a natural fortress where they could elude both the U.S. Army and the Texas Rangers.

The two opponents skirmished frequently in the following weeks, eventually winding up in Blanco Canyon in the Staked Plains. In the early hours of October 10, Parker and his warriors fell upon the U.S. Army soldiers with blood-curdling yells. The Comanches rang bells and shook their thick buffalo robes in an effort to stampede the soldiers’ horses. The troopers held on to some of their horses, but lost 70 of their mounts to the Comanches. Later that morning the Comanches stole a dozen more horses, prompting two officers and a dozen troopers to take pursuit.

The troopers soon discovered to their horror they had been led into an ambush. After a few rounds were fired more than half the troopers and an officer galloped away. The remaining five men and a lieutenant slowly fell back, firing as they did. Swinging into the saddle, the remaining soldiers attempted to escape when one of their horses faltered.

Parker wove his way toward the trooper with the weakened mount, using him as cover from the fire of the remaining soldiers. Parker eventually shot the soldier in the head. When he spotted the main column of the enemy bearing down on him, Parker and his warriors fell back, slowly trading shots with the Tonkawa scouts leading Mackenzie’s advance.

The cavalrymen eventually located Parker’s former village. The trail of the escaping Comanches was plain enough with their dragging lodge poles and numerous horses and mules. Parker attempted to confuse his pursuers by dividing the Comanches and animals into two groups and having them cross and recross their trails. The tactic fooled the Tonkawa scouts into believing that the Comanches had doubled back on them. The next morning, the Tonkawa scouts picked up the Comanche trail, which led up the steep walls of the Blanco Canyon. The soldiers followed the Comanches out of the canyon, but Parker sought to elude Mackenzie’s men by leading his people back into the canyon. The Tonkawas once again picked up the trail, and the soldiers entered the canyon again only to discover that the Comanches had gone up the bluffs on the other side.

A storm blew up prompting Mackenzie to halt his command in order to give his men a much needed rest. The Comanches, though, rode on through the storm and succeeded in escaping their pursuers. Although Mackenzie’s force tried to pick up the Comanches’ trail in the canyon the following day, they were unsuccessful. Although outsmarted by Parker in what became known as the Battle of Blanco Canyon, Mackenzie familiarized himself with the Comanches’ trails and base camps in the following months. This would allow him to lead future operations with a greater prospect of success.

In September 1872 Mackenzie attacked a Comanche camp at the edge of the Staked Plains. He destroyed their village; in the process, he killed 23 warriors and captured 124 noncombatants. He also snared a good size herd of horses and mules, the care of which he entrusted to his Tonkawa scouts. True to form, Parker’s Comanches recovered their horses. Nevertheless, Mackenzie’s 1872 expedition came as a severe blow to the Comanches. Many Comanches straggled back to the reservation in hopes of getting back their women and children.

Parker, who was not at the village when Mackenzie attacked it, continued to remain off the reservation. The Comanches received a badly needed reprieve the following year when Mackenzie was bogged down in operations along the U.S.-Mexican border.

The winter of 1873-1874 proved to be a hard one not only for Parker and his band, but also for Comanches living on the reservation. The reservation Comanches found government rations either nonexistent or of poor quality. As a result, many Comanches were forced to eat their horses.

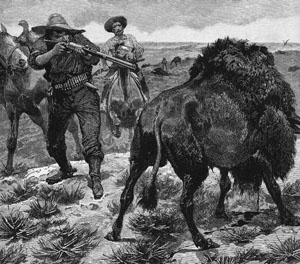

The Medicine Lodge Treaty had granted the Southern Plain tribes exclusive rights to buffalo hunting between the Arkansas and Cimarron Rivers. But in 1874 white buffalo hunters from Kansas converged on the region in large numbers to kill buffalo. Armed with 50-caliber Sharps rifles, the whites flaunted government regulations and began hunting buffalo year round for their hides on land specifically set aside for Native American hunting. To process the hides for shipment to the East, they established supply depots. In response, the Comanches launched repeated raids in which they sought to curtail the activity.

The Comanches who needed the buffalo for food had a particular hatred for these men who killed buffalo, not for food, but for the hides alone. Many in the U.S. Army, though, had a completely different opinion of the buffalo hunters who were systematically destroying the Native Americans’ food source. “For the sake of a lasting peace, let them kill, skin and sell until they have exterminated the buffalo,” said General Phil Sheridan, commander of the Military Division of the Missouri.

With the situation looking increasingly grim for the Comanches, a medicine man named Isa-tai, who claimed to be the Great Spirit, claimed to possess magical powers that would make the Native Americans immune to the white man’s bullets. Isa-tai prophesied that the Comanches would regain their former glory and drive out the whites. With the help of Parker, Isa-tai spread his message to the various tribes of the Southern Plains.

A large gathering was held along the Red River in May 1874, not far from the reservation. Half of those in attendance agreed to follow Parker and Isa-tai in a desperate bid to drive the whites off the Southern Plains. During the war councils held at the gathering, Parker said he wanted to raid the Texas settlements and the Tonkawas. The tribal elders had other ideas, though, telling Parker that he should first attack the white buffalo hunters. The elders told Parker that after the buffalo hunters were wiped out, he could return to raiding Texas settlements.

A war party of approximately 300 Southern Plains warriors, including Parker’s Quahadis, struck out for the ruins of an old trading post known as Adobe Walls where the buffalo hunters had established a supply depot. Expecting to catch the 29 whites asleep, Parker and his war party touched off the Second Battle of Adobe Walls in the early morning hours of June 27.

To the Comanches’ surprise, the buffalo hunters spotted them as they approached. “Hundreds of warriors, the flower of the fighting men of the southwestern plains tribes, mounted upon their finest horses, armed with guns, and lances, and carrying heavy shields of thick buffalo hide, were coming like the wind,” wrote buffalo hunter Billy Dixon.

The buffalo hunters stood their ground. The Comanches made repeated assaults but were repulsed each time. As always, Parker was in the thick of the action. At one point, he backed his horse to the door of one of the buildings in a vain attempt to kick it in. Another time, he ignored the hunters’ gunfire and leaned down to retrieve a badly wounded warrior.

But bravery alone was not enough to defeat the buffalo hunters with their long-range Sharps rifles. At one point, they shot Parker’s horse from under him from one of the outpost’s buildings at 500 yards. Taking cover behind a buffalo carcass, Parker was struck in the shoulder by a ricochet. After a few more warriors and horses, including Isa-tai’s mount, were hit at great distances, the fighting died out for the day. The siege continued for two more days, but the Comanches eventually withdrew.

Angered over their defeat, the Comanches attacked other settlements. But their efforts to stop the white buffalo hunters came to naught. By the end of the summer, only about 1,200 Comanches, of which 300 were warriors, were still holding out in Comancheria. They shared their territory with a similar number of Southern Cheyenne and Kiowa who refused to live on the reservation.

It was the beginning of the end for the Comanches when five mounted columns, composed of the 4th, 10th, 8th and 6th Cavalry Regiments along with the 5th and 11th Infantry Regiments, set out in August to defeat the remaining non-reservation people from the Southern Plains tribes. Mackenzie commanded three of the five columns. The U.S. Army burned villages and seized horses in order to cripple the last Southern Plains holdouts from reservation life.

This concerted campaign by the U.S. Army proved disastrous for the Comanches and their Kiowa allies. The Army regiments steadily wore them down in countless clashes and skirmishes. On September 28, the Comanche and Kiowa suffered a crippling defeat when Mackenzie swept through Palo Duro Canyon in the Staked Pains, destroying their village and capturing 1,000 horses. After giving a few hundred of these animals to his Tonkawa scouts, Mackenzie ordered the rest of the horses shot to prevent the warriors from recapturing them. Throughout the following winter, many of the remaining Comanche and Kiowa in the Staked Plains surrendered to the Army.

Parker, who was not present at the Battle of Palo Duro, continued to hold out with his followers, dodging army patrols and continuing to hunt the quickly vanishing buffalo. But by the spring of 1875, he realized that further resistance was futile. On June 2 Parker arrived at Fort Sill where he surrendered to Mackenzie.

Once on the reservation, Parker worked hard to keep the peace between the Comanches and the whites. In an attempt to unite the various Comanche bands, the U.S. government made Parker the principal chief. He took his role seriously and did what he could for his people. He urged them to learn how to farm and ranch.

In 1901 the Federal government subdivided the reservation into 160-acre parcels of land, which compelled many of the Comanches to move away. As for Parker, he prospered as a stockman and businessman, but he remained a Comanche at heart. Proof of this was that when he died on February 24, 1911, he was buried in full Comanche regalia.