By Eric Niderost

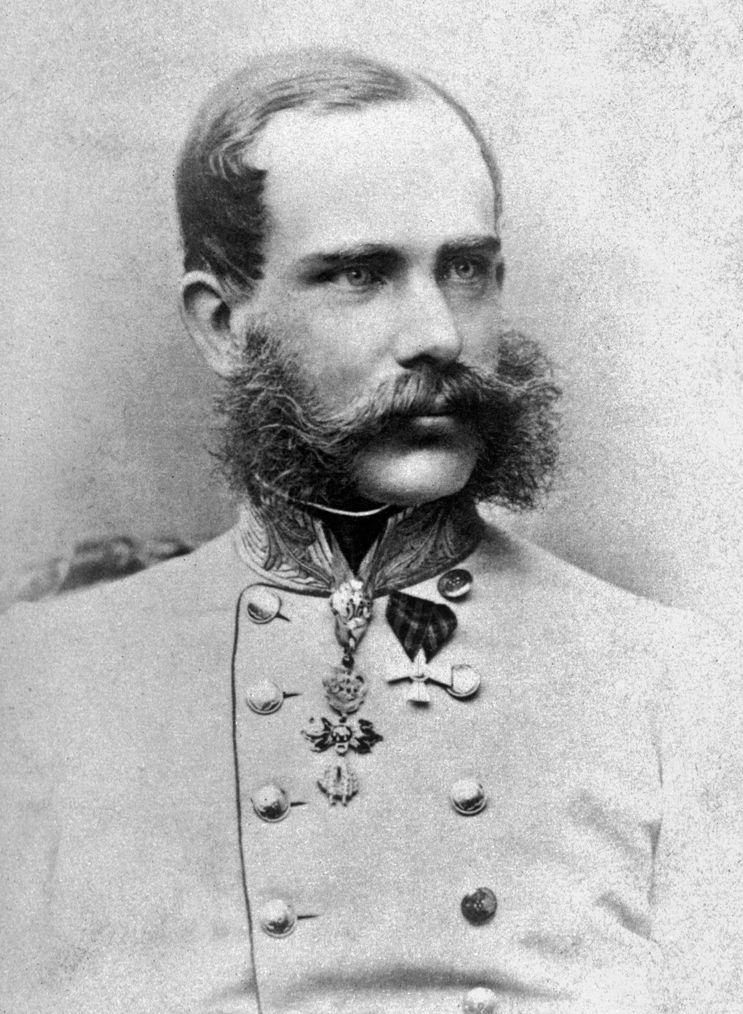

On April 20, 1859, Emperor Franz Josef paid a respectful visit to Prince Klemens Wensel von Metternich’s place at Rennweg in Vienna. Metternich was a legend in his own time. The prince was occasionally reviled but also revered as statesman with an international reputation. Metternich was a leading figure in European politics and diplomacy in the decades just following the turbulent Napoleonic Wars. Although the 86-year-old had been out of power for more than a decade, the Austrian emperor still sought his advice.

Franz Josef wanted Metternich’s opinions on the diplomatic crisis that was developing between Austria and the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia, one of the small states that made up the Italian peninsula. Curiously, the emperor seemed to want validation on decisions already made, not guidance on future policy.

The old statesman was hard of hearing, mainly because of his advancing years, but Franz Josef was deaf in another way. In particular, he seemed to be fatally immune to good advice. As the interview progressed, Franz Josef’s bellicose intentions were becoming obvious, and as the muffled words reached Metternich’s brain he felt a sense of growing alarm. The aging statesman was a reactionary, a defender of absolutism and the old order, but at the same time he was a man who was dedicated to the balance of power and the maintenance of peace in Europe.

Finally Metternich could stand no more. “For heaven’s sake, send no ultimatum to Italy!” he said. By Italy he meant Piedmont-Sardinia, and Franz Josef hardly knew how to reply. The emperor, perhaps a little embarrassed, had to admit that the ultimatum already had been sent. It was done, and there was no turning back. Sardinia-Piedmont was Lilliput- ian compared to Austria, but it had a powerful ally in the form of French Emperor Napoleon III, whose full name was Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte. This ultimatum was going to set off a chain of events that led to the Franco-Austrian War of 1859, a conflict sometimes called the Second War of Italian Independence.

In 1859 Italy was a geographical expression, not a politically unified nation. The Italian peninsula was divided into a patchwork of independent states, the most powerful of which was Piedmont-Sardinia, a northern kingdom ruled by Victor Emmanuel II of the House of Savoy. Allowing for regional differences, its states shared a common culture, language, religion, and rich heritage that dated back to Roman times. The Duchies of Tuscany, Parma, and Modena were in some respects artificial creations that could be easily swept aside if momentum for unification took hold. The Kingdom of the Two Sicilies occupied the lower half of the boot of Italy. It was a medieval, corrupt state whose people were mired in poverty and ignorance. Central Italy boasted the Papal States, the territories the Roman Catholic Pope ruled as a temporal, not spiritual leader. Pope Pius IX was a bit of a political reactionary who was not about to give up his earthly powers voluntarily. Still, many Italians dreamed of Risorgimento, that is, the birth of Italy as a unified nation.

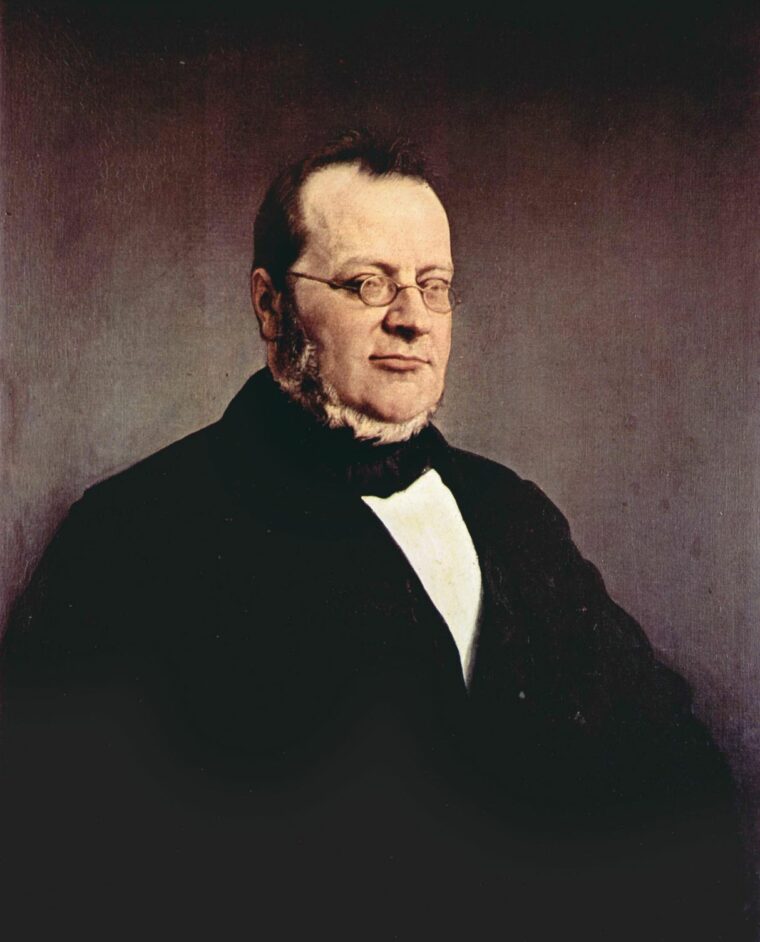

Camillo Benso, Count of Cavour, who had been Piedmont-Sardinia’s prime minister since 1851, was one of those dreamers. Balding, slightly chubby, with a thin line of whiskers that circled his face like a bib and left his chin and upper lip bare, he looked more like a small-town businessman than a master politician. But appearances were deceiving. Cavour was a passionate Italian nationalist who was a grand master of diplomatic chess, a hard-headed, coolly methodical politician who had few equals in Europe.

Cavour knew that Italian unity and ultimate independence would not be achieved without the expulsion of Austria from the peninsula. Austria held Lombardy and Venetia, key parts of Italy that were vital to the creation of a unified state. The two provinces were also Austrian bases where Franz Josef’s Second Army could be used to suppress any nationalistic, democratic, or liberal uprisings.

The Count of Cavour knew Piedmont-Sardinia could not take on Austria alone, and France was the most logical ally if war should break out. Napoleon III was an inveterate schemer. He was an unscrupulous politician who was not above censoring newspapers and jailing or exiling opponents of his regime. Yet he also had a romantic streak and even an idealistic side as well. He was genuinely sympathetic to Italy’s plight.

He had spent some time in Italy as a young man, and while there had joined a secret revolutionary movement called the Carbonari (charcoal burners). The members of the Carbonari were fierce Italian patriots and as such vehemently anti-Austrian. Young Louis- Napoleon jumped into the movement with both feet, distributing revolutionary pamphlets and generally delighting in being a subversive. His revolutionary period was brief but remained with him the rest of his life.

The wily Cavour first began efforts to win over the French emperor to Piedmont’s side. His cousin, the ravishingly beautiful if slightly eccentric Virginia Oldoini, Countess of Castiglione, was dispatched to try and win Napoleon over to the Italian cause. Although already married, she created a minor scandal by becoming Louis-Napoleon’s mistress for two years. Scandal was nothing to the avant-garde countess.

An avid patron of photography, she delighted in being shown barefooted and sometimes barelegged, though in all other respects modestly dressed. In the Victorian period, when women wore long dresses and hoop skirts, showing legs or bare feet was a titillating endeavor. Apparently she did her job well for Louis-Napoleon seemed to favor her cause as well as her charms.

There were other considerations as well. Napoleon III was eager to emulate the military successes of his uncle, Napoleon I. For this reason, northern Italy was an almost irresistible lure. It was in that region, after all, that the first Napoleon had won fame and everlasting renown. The battlefields of northern Italy, with names like Lodi, Rivoli, and Marengo, were milestones of the Napoleonic legend that still resonated with the French public.

Yet Napoleon III’s idealistic streak, while gen- uine, only went so far. If an Austrian war was successful, Piedmont-Sardinia would be enlarged, which was a vital step in Italian reunification. But Napoleon III wanted payment in the form of some territory for France. Cavour, his eyes on the greater prize of unification, happily sweetened the secret deal. Among other things, France would get Savoy. But there was something else; namely, the French emperor would not budge unless Austria was the aggressor.

Cavour was sure he could arrange something, and with little trouble on his part. He was right. The wily minister simply massed troops along Piedmont’s border with Austrian- occupied Lombardy and waited for Vienna’s predicable reaction. It was not long in coming. Emperor Franz Josef I took the bait, and his government issued the ultimatum that had upset Metternich. Cavour rejected the ultima- tum out of hand, so at last the Franco-Austrian war was a reality.

The Lombard plain was going to be the future theater of war. Situated between the tow- ering Alps in the north and the great Po River in the south, it was richly veined with the Po’s many swift-flowing tributaries, including the Sesia, Ticino, Adda, Oglio, and Mincino. The Po River itself was large, 550 yards across at Valenza, and had comparatively few masonry bridges across its broad expanse. From a logistical standpoint, the region’s many canals, vine- yards, and forests made the movement of large armies difficult, especially cavalry.

The Franco-Austrian War, like the near-contemporary American Civil War, was a transi- tional conflict that was modern in some respects, but also embodied traditional methods as well. From a modern standpoint, the Franco-Austrian War was the first to effectively employ travel by rail. The railroads were revolutionary for the time, and the French in particular used them extensively. The French army used two routes to get to the front, and trains were important elements in both.

In one instance, Gallic soldiers in northern France boarded trains that took them to Marseilles or Toulon and then transferred to troop transports for a sea journey to Genoa. The alternative was an all-land route that involved taking trains to the French side of the Alps at St. Jean de Maurienne, marching through the mountains via the Mount Cenis Pass, and picking up trains on the Italian side at Susa. The Susa railway provided easy transportation to Turin, the Piedmontese capital. The Mount Cenis Pass was choked with snow, but 4,000 workers managed to clear it in time for the foot- slogging French infantry to get through.

The telegraph was also a new and revolutionary tool for war. Napoleon III stayed in Paris in the early weeks but kept the telegraph wires hot with a stream of orders to his far- flung troops. Frequent incoming messages also kept him abreast of ever changing political and military events as they unfolded. The emperor left Paris for the south of France on May 10, intend- ing to take a ship like many of his soldiers. He arrived in Genoa aboard the Queen Hortense and joined his assembling army at Alessandria by May 14.

The Austrian army reflected in microcosm the strengths and weaknesses of the empire at large. The ranks were filled by peasants from the various ethnic groups that made up the sprawling multinational empire. Literally a polyglot force, the Austrian army recognized no less than 10 languages, though German was the language of command. At times officers had to use translators to address their men.

Nationalism was also stirring among Franz Josef’s subjects, and this too was reflected in the Imperial armed forces. There were ethnic Germans, Hungarians, Slovenes, Poles, Czechs, Ruthenians, and Serbs. The Hungarians had fomented their own revolution in 1848; it had been suppressed and resentment still lingered. The Italians were also considered unreliable, and apt to desert at the first opportunity.

The typical white-coated Austrian soldier was armed with a muzzle-loading Lorenz rifle-musket, but some units still had old-fashioned smoothbores. By and large, the Austrian light infantry was excellent, especially the skirmishing Jäger units. The Croatian light infantry was also excellent, albeit politically unreliable. Austrian officers commanding such men never knew if the sol- diers would take it into their heads to shoot them instead of the enemy.

By contrast, the French army was homogeneous, generally well equipped, and brimming with confidence and élan. The army had performed well in Algeria and the Crimea and had gained valuable combat experience. French infantry were armed with percussion cap, muzzle-loading rifle muskets, just like their Austrian enemy; however, it was a Gallic article of faith that the increased accuracy of these weapons could be neutralized by a rapid advance across a field in a bayonet charge.

The French soldier had a sharp uniform that underwent little change until 1914 and the begin- ning of World War I. It consisted of a dark blue greatcoat with turnbacks, red trousers, and a forage cap with a visor known as a kepi. The kepi, which was adopted by the Americans in their civil war, largely replaced the stiff and relatively heavy leather shako. Only Napoleon’s Imperial Guard grenadiers harkened back to an earlier time with their splendid bearskin headdress.

The French did have an advantage in artillery. Louis-Napoleon was not strictly speaking a soldier, but he was interested in artillery and had written intelligently on the subject. The French army was the first in the world to adopt rifled cannons, which greatly improved range and accuracy. In contrast, tradition-bound Austria kept smoothbore guns.

The 60,000-strong Piedmont-Sardinian army was, like the French, a homogeneous force enjoying the same language, customs, and goals. King Victor Emmanuel II was a competent soldier who at one point actually led his men into battle; he was the last European monarch to do so. The Piedmontese also boasted fine light infantry, in particular the feather-hatted Bersaglieri. Far more controversial were the Cacciatori delle Alpi. Two thousand of these Hunters of the Alps were attached to the Piedmont-Sardinian forces. These irregulars were led by Giuseppe Garibaldi, an out-and- out revolutionary who had an unsavory reputation in conservative circles.

The campaign began with an Austrian invasion of Piedmont-Sardinia on April 29, 1859. This made strategic sense, because if pushed vigorously the Piedmontese might be knocked out of the war and forced to sue for peace before the French arrived in sufficient numbers to come to their aid. The Austrian Second Army was the main part of this effort, with 107,000 men and 364 guns. As it crossed the Ticino River boundary that separated Piedmont from Lombardy, the Austrians were confident they could take Turin, the enemy’s capital, only 75 miles away.

The Hungarian-born general who commanded the Austrian army was Field Marshal Count Ferenc Gyulay. Despite his lofty title, he lacked real experience in the field. At 69 he was an able administrator but tended to be slow, overcautious, and easily frightened if the tide of events seemed to turn against him.

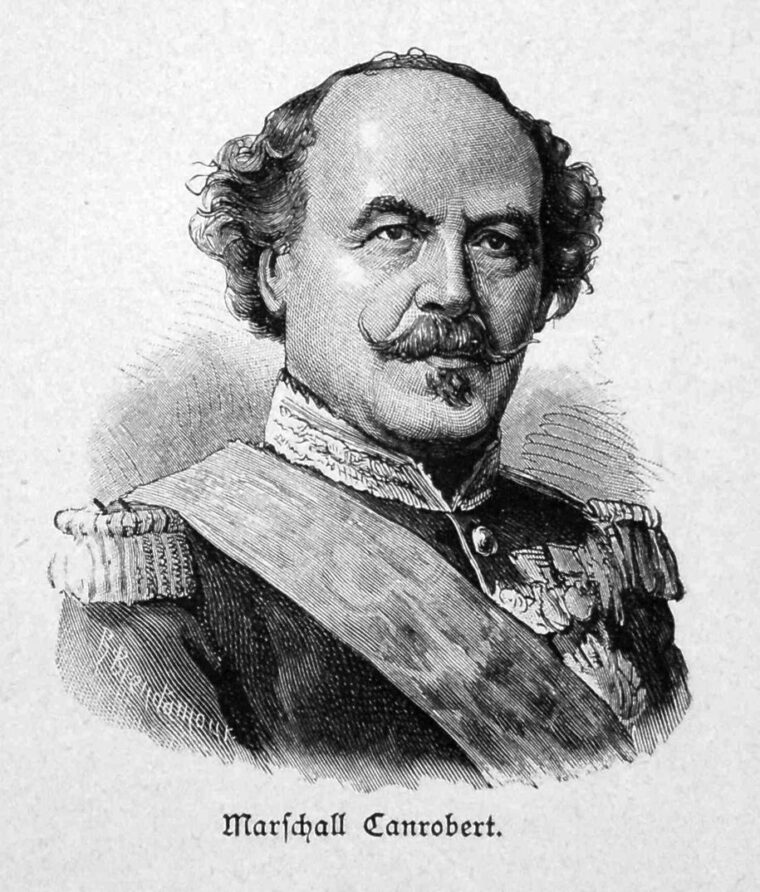

In the meantime, the Piedmontese got some timely advice from Marshal François de Certain Canrobert, commander of the French III Corps. His men were still trudging over the Alps, but Canobert had arrived with an advance partly to size up the situation. Instead of a direct defense of Turin, Canobert suggested that the Piedmontese move four of their five divisions south by rail to the fortifications around Alessandria and the Po River bridgehead at Casale.

Such a savvy move for the Allies would cover all possible scenarios. If Gyulay insisted on advancing on Turin, the Piedmontese forces in the south could threaten his left and his line of communications. If somehow he turned south and tried to besiege Alessandria, the Piedmontese would simply hold out, confident that powerful French forces now gathering in Genoa would sooner or later come to their aid. The Piedmontese accepted the advice with alacrity.

As Canobert predicted, Gyulay did indeed become worried about the threat to his left, and reports of French arrivals in Genoa did nothing to assuage his concerns. That was bad enough, but heavy rains drenched the Austrians, overflowing river banks, turning roads into quagmires, and generally dampening a morale that wasn’t high to begin with. It took effort to slog through mud in pouring rain, and the troops were plagued with fatigue.

After four days of marching, the Austrian army had advanced only 20 miles. Unable to contain his growing anxiety, Gyulay ordered a retreat back to Lombardy. Soon the dejected white coats had retired behind the Ticino, leaving Piedmont safe and at the same time handing the initiative over to the Allies. By mid-May the French and their Piedmontese colleagues were ready to take the offensive. Napoleon III’s contribution to the upcoming campaign included five corps and his Imperial Guard, a total of around 170,000 men.

Gyulay did try an abortive reconnaissance in force with 20,000 men, but he fell back after a clash at Montebello. Thereafter the Austrians adopted a passive, defensive mode, in part because Gyulay was lethargic by nature, and also because he knew Austrian reinforcements were coming that would boost his numbers.

With Piedmont safe from invasion, the Allies’ next task was to liberate Lombardy from Aus- trian control. As a first step they would cross the Ticino and march on Milan, the capital of Lombardy. The Ticino was unfordable, but the river was bridged at San Martino, a village along the main road to Milan. The Austrians, realizing the San Martino bridge’s importance, built a redoubt on the river’s western bank to protect it.

Seven miles north of San Martino was the village of Turbigo, which offered some possibilities. It too was on the Ticino River, and that stretch of the waterway did not seem to be guarded. Napoleon ordered Maj. Gen. Jacques Camou, commander of the Voltigeur Division of the Imperial Guard, to secure a bridgehead there.

A French officer nostalgically recalled the moment when the Imperial Guardsmen marched off to fulfill their assignment. “Nothing could be finer than to see these magnificent troops parading in the streets of [Novara], with drummers beating and a band leading the way, before going to prepare the invasion of the enemy territory,” he wrote. Camou reached Turbigo with no difficulty, and, since there was no bridge there, sappers quickly constructed three pontoon bridges across the Ticino. They were ready by dawn on June 3.

Napoleon was more politician than soldier, and was nothing if not an inveterate gambler, trusting to luck with a casual throw of the dice. In the course of his turbulent career he had seen many ups and downs; at one point, he had even been in prison. But once Louis-Napoleon secured the imperial crown he must have felt he was on a roll. Trusting to luck, and his own gambler’s instincts, Napoleon decided on a two-pronged offensive whose ultimate goal was to open the main road and capture Milan.

Once a bridgehead was secured, Camou, who was responsible for carrying out the first prong, was to advance southward to the village of Magenta. The effort would include Maj. Gen. Patrice de MacMahon’s II Corps and the Piedmontese army, at least if all went according to plan. The second prong was spearheaded by the Grenadier Division of the Guard and would cross the Ticino at San Martino and proceed eastward to Magenta. The village was the critical rendezvous point, with the two prongs uniting before continuing on to capture Milan.

Napoleon III’s plan was fraught with danger and violated a key precept of military science: never divide your forces when the enemy’s exact whereabouts or numbers are unknown. Napoleon Bonaparte, one of the greatest military geniuses of history, would have been appalled at his nephew’s rash maneuvers. If one prong was attacked and got into trouble, the other would be virtually powerless to come to its aid. What is more, there were no telegraph lines in the immediate region, so the French would have to fall back on old-fashioned dispatch riders to relay messages from command to command.

The clash at Magenta is often called a meeting engagement, meaning neither side had anticipated serious fighting there. On June 4 Gyulay had intended to give his tired troops a day of rest after their exertions during the abortive Piedmont campaign. He had only the Austrian II Corps, the majority of the I Corps, a cavalry division, and part of the VII Corps available for battle. Other units, such as the III Corps, were within marching distance, at least in theory, but the Austrian army was still in disarray and straggling was the norm after the Piedmont fiasco.. Ironically, the awkward Austrians were actually in better overall shape than the Allies, at least when it came to numbers. Altogether, Gyulay had approximately 60,000 men.

By contrast, the Allies seemed unable to act in concert. Victor Emmanuel and his Piedmontese army remained idle at Turbino all day, leaving the main burden of the Magenta fight to 48,000 Frenchmen. This was later to cause some bitterness among the French when they reviewed the events of the day. Despite this, the Gallic troops moved forward with their customary zeal.

The Austrians attempted to blow up the bridge at San Martino, but they did not have blasting powder available. Ordinary powder was used, so the damage was only partial and largely confined to two arches. Battered but unbroken, the bridge was passable to infantry and could, in any case, be repaired. French engineers lost no time in repairing the span, and as an added measure constructed a pontoon bridge 300 yards away.

The Grenadiers of the Imperial Guard were the first to reach San Martino, arriving at 10 AM on June 4. Emperor Napoleon and his staff arrived a half an hour later. It was nearing midday when the emperor heard the sound of thunder from the north, and in the distance, just beyond the trees, smoke rose in great clouds. These were telltale signs that MacMahon had started his offensive from the Turbino bridgehead.

Once past the Ticino River, the guardsmen found that they had to cross a broad plain two miles long. Slightly to the right of their approach was a steep embankment, a natural rise, though it almost looked like a man-made earthwork. Just east of this rise was the Naviglio Grande Canal, a waterway that paralleled the Ticino River. The canal was 30 feet wide and three feet deep, but its current was very strong so it could not be crossed on foot.

To make matters worse, the canal’s sides were steep, and thick clusters of prickly acacia grew abundantly along its banks. Four local bridges spanned the canal, but the Austrians had managed to destroy only two of them, those at the village of Boffalora to the north and Ponte Vecchio to the south. This left intact the bridge at Ponte Nuovo, which carried the main road to Milan, as well as a railroad bridge that was part of a rail line that paralleled the main road all the way to the Lombard capital.

The 2nd Grenadiers of the Guard surged forward toward Boffalora only to be stopped dead in their tracks when they discovered the bridge had been blown up. They had to satisfy themselves with firing at the white coats across the canal. Not too far away the 3rd Grenadiers of the Guard advanced though the broad open plain under fire. Their progress was hampered by the fact it had rained some time before and the plain was partly flooded in spots. The guardsmen had alternately to wade knee-deep through water and slog ankle-deep in mud.

Quickly shedding their heavy knapsacks but still retaining their famed bearskin headdress, the guardsmen climbed up the embankment slope without bothering to fire. The Austrians, who were startled by the sheer audacity of the Gallic effort, fell back. But the French had not yet crossed the bridge that spanned the Naviglio Canal at Ponte Nuovo. Some of the Imperial Guard Grenadiers managed to take the two houses on the west bank of the canal opposite Ponte Nuovo, but when they attempted to actually cross the span they were repulsed by heavy fire from the 60th Austrian Infantry Regiment.

Undeterred, Brig. Gen. Jean Joseph Gustave Cler brought up the Zouaves of the Guard to see what they could do to cross the bridge. The Zouaves were originally of Algerian origin, and although by the 1850s they were mostly Frenchmen, they still retained the Turkish costume with baggy pants that some U.S. and Confederate units adopted during the Civil War.

The Zouaves went forward in a rush. As they crossed the Ponte Nuovo bridge their enthusiastic shouts of “Vive l’Empereur!” could be distinctly heard over the rattle of musketry and deep-throated roar of cannons. The Zouaves took the two customs houses located just on the other side of the bridge, but it was no easy task. Austrian soldiers kept up a galling fire from each window, but the fierce Zouaves took the building with the cold steel of their bayonets.

The Imperial Guard grenadiers also participated in this mad scramble, and when the customs points were taken many placed their bearskins on the ends of their rifles and waved them ecstatically. The attack was well timed because the Austrians were in the midst of making final preparations to blow the bridge. A quick-acting Zouave bayonetted the Austrian engineer who was about to light the fuse. Six barrels of gunpowder were in place for the demolition. The French soldiers quickly and unceremoniously rolled them into the canal.

But the Austrians launched a powerful counterattack, capturing a French gun, and retook the houses at Ponte Nuovo on the east bank of the canal. The Imperial Guard Grenadier Division was now isolated, desperately clinging to its foothold along the canal, ferociously attacked again and again by fresh Austrian units as they arrived on the battlefield. These men were the elite of the French army, tough and resilient, but still only flesh and blood. They needed assistance.

Messengers who galloped to Napoleon III at San Martino received the same reply. “I have nothing to send,” said the French emperor. “Hold on.” Other couriers were sent to find the French III and VII Corps, which had not yet appeared, because the main road from Novara was clogged with a major traffic jam.

After holding on courageously for about an hour, the Guard Grenadiers were rescued by elements of Marshal François de Certain-Canrobert’s III Corps. Seeing the red trousers and kepis of their comrades in arms, which stood out so differently from the white coats of the enemy, the guardsmen knew they had been rescued. Their joy and relief took audible form as they cheered with all their remaining strength.

But the respite was only temporary. The guardsmen managed to retake the customs houses. The fighting seesawed back and forth with increasing ferocity. The village of Ponte Vecchio changed hands no less than six times in the course of the afternoon. The fortunes of war ebbed and flowed as more units from both sides entered the fray.

At one point it seemed that the Austrians were on the cusp of victory. Gyulay had sent a premature message to Vienna announcing his triumph. Yet victory was elusive. The countryside was stitched with vineyards, walls, and other obstructions that impeded the movement of the Austrians as much as the French. Austrian staff work was sloppy and confusing as well. The army’s multinational nature was yet another weakness. Scores of Italian soldiers from Archduke Sigismund’s Infantry Regiment deserted whenever they saw an opportunity.

MacMahon’s II Corps had still not arrived on the scene. If it did not appear soon, all hope of achieving a French victory would be gone. MacMahon was a competent soldier, but stiff Austrian resistance and the nature of the countryside impeded his progress. The lush green fields were broken up by countless irrigation channels, rows of trees, and dense patches of mulberry bushes that limited visibility and impeded marching and fighting.

In spite of all the difficulties, MacMahon did make progress. At one point MacMahon’s advance units halted and waited for the rest of the corps to catch up. Magenta, their primary objective, could be seen a mile and a half away. From a distance the town looked picturesque, a dreamy and romantic vision with its narrow streets, red tile roofs, and ochre walls so typical of ancient Ital- ian communities. But Magenta was about to be transformed into a charnel house, a place where the smell of gunpowder was going to mingle with the sickly sweet stench of blood.

The II Corps contained the 1st and 2nd Etranger, a relatively new unit nearly 30 years old. It was young in comparison to regiments that traced their lineages back to Bourbon France, but it was already gaining a reputation that would becoming legend. The 1st and 2nd Etranger were in fact the French Foreign Legion, and the 2nd Zouaves were part of their battalion.

These troops began moving again, and a cavalry screen of the 7th Chasseurs a Chaval passed through their ranks on the way to the rear. The troopers were being driven in by three columns of Austrian infantry. It was the first inkling of trouble for the Legionnaires. A captain with the 1st Etranger was the first to spot the white-coated ranks in the distance. Impulsively, he ordered a charge even though in effect he was launching an offensive with a single company of soldiers.

But support was on the way. Colonel Louis de Chabriere, commander of the 2nd Etranger, ordered his men to drop their heavy packs and charge, but the words were scarcely out of his mouth before he was hit by an Austrian bullet that knocked him from his saddle. Chabriere was dead, but his last order was obeyed to the letter. The Legionnaires and Zouaves became a human tidal wave of blue and red as they clambered over walls, squeezed through grape vines, and negotiated through blinding clouds of powder smoke.

Many Austrian prisoners were taken, but only the outskirts of Magenta had been cleared. The Legionnaires and the Zouaves paused to regroup and reform before carrying out the final assault. It was at this precise moment that MacMahon trotted up to the assembled ranks. He was a man of military bearing, dignified with his red kepi and mustache and goatee. “The Legion is here! The affair is in the bag!” he said. His words gave the men fresh heart.

Just as they were about to attack, Imperial Guard units came on the scene and formed up to join them. The Guard, which had already participated in some heavy fighting, was composed of men who were for the most part old soldiers. Nevertheless, regimental rivalries were always present, especially when there was a chance of glory. The hardbitten Legionnaires filled the air with derisive catcalls. “TheGuard?” they shouted. “Get them out of here! Let them stand guard at Saint Cloud! The chambermaids of the Tuileries will be too sad if they get hurt!” But such verbal sniping was quickly forgotten when the order was given to advance. The French troops swarmed into Magenta and a virtual meat grinder. This is where the term “soldier’s battle” is particularly apt. All cohesion was lost; serried ranks and proud battle flags were replaced by hand-to-hand fighting of the most desperate kind. The narrow streets were clogged with the bloodied bodies of friend and foe alike, and each house was a miniature fortress defended by white- coated soldiers determined to hold on at all cost.

Officers were in the thick of the fight and suffered accordingly. Lt. Col. Antonio Martinez of the Foreign Legion was probably so full of adrenaline he scarcely noticed the fact that a bullet had torn away his left eyelid. Ignoring the rivulets of blood that coursed down his face, he ordered the axe-wielding engineers to break down doors so infantry could gain interior access. Martinez ordered others to climb stairs to deal with white-coated riflemen on second stories.

The Austrian defenders—some of whom were not even ethnically German—were stubborn. The Croatians might have been politically unreliable, but at Magenta their rifle fire was accurate and deadly. The same held true for the Tyrolian riflemen, whose marksmanship was rightly respected. These troops made it exceedingly difficult to take Magenta. It had been a town of 4,000 residents before the battle, so there were quite a lot of buildings to take one by one.

In these claustrophobic and murderous conditions, even generals fought like common soldiers. Maj. Gen. Marie Esprit Espinasse led the 2nd Zouaves into Magenta on horseback, but the steed was having trouble walking down a narrow lane that was clogged with dead and wounded. “We can’t stay on this moving ground,” he said, referring to the writhing wounded who were trying desperately to drag themselves to safety.

Espinasse dismounted, but moments later his orderly, Lieutenant Andre de Froidfond, was struck in the stomach by a bullet. The young man fell heavily against a nearby wall. Looking around amid the confusion and noise of battle, a sharp-eyed Espinasse saw that the shot had come from a multistory building that stood on a street corner. A pile of corpses bore mute testimony to the fact that the French had tried to take the building but failed.

“We must take it at all costs!” said Espinasse. He led the Zouaves over to the structure, ignoring the shots that peppered the air and ricocheted off the street. Espinasse ran up to the door and beat on it with the pummel of his sword. “Come my Zouaves!” he said. “Break down this door!”

But when the door refused to give way, Espinasse turned his attention to a nearby ground floor window. He pounded on the window’s metal frame in an effort to be heard over the noise of battle, urging his men to go in through the window. But a bullet fired at close range from that same window hit Espinasse, mortally wounding him.

The bullet had broken the general’s arm and then punched into his kidneys. The bullet’s impact was so great that Espinasse dropped his sword and slumped to the ground. But the Zouaves, enraged at their leader’s fate, lost no time in breaking into the building to avenge him. Those Austrians not willing to surrender were put to the sword.

The battle raged on, though the fighting slowly died down. By 8:30 PM the French had captured Magenta, and the Austrians were withdrawing. It was a victory, but the French were exhausted and hardly in a celebratory mood. Many French soldiers broke into wine cellars where they wound up dead drunk. They were not celebrating; rather, they were trying to temporarily forget the horrors they had witnessed that day.

The French lost more than 4,500 dead and wounded, but the Austrian butcher’s bill was even higher, totaling 5,700 casualties. The French also took 4,500 prisoners. Napoleon III, seeking to honor MacMahon’s slow but crucial intervention, made him Marshal of France and Duke of Magenta. Yet it was the soldiers, particularly the rank and file, who deserved the glory. Emperor Napoleon was a mere spectator through much of the fight, showing little of his uncle’s admittedly rare genius. The French also were fortunate that the Austrian leadership was third rate and often incompetent.

Magenta did not end the war. Another more sanguinary fight would occur at Solferino, a battle so bloody it would spur the creation of the International Red Cross. It was another French victory, but Napoleon III was deeply shaken by the horrific sights he saw. Napoleon’s instincts as a politician kicked in, and he made peace with rival emperor Franz Josef. The pact fell short of Cavour’s ambitions, but a start had been made as Piedmont-Sardinia annexed Lombardy.

That same year a French chemist named François Verguin created a new reddish-purple dye. Hearing of the French victory, he unwittingly gave the battle a kind of immortality by naming the new color magenta.

A perfectly useless military action that only emboldened Louis Napoleon to later think he could take on Bismarck in the Franco-Prussian War. That disaster then set the stage four decades later for WW I, whose effects are still felt today.