By David A. Norris

At dawn on August 21, 1863, 450 Confederate Irregulars under William C. Quantrill descended on the town of Lawrence, Kansas. To Quantrill’s men, Lawrence was a center of Union loyalty and the focal point of their hatred. They would leave the town in ashes and its streets filled with dead men. At the top of their lethal agenda in Lawrence was the capture of the number one enemy of the secessionist Border Ruffians of Missouri: U.S. Senator James Henry Lane of Kansas.

Born in Indiana in 1814, James Henry Lane was the son of lawyer and congressman Amos Lane. Lane followed his father into the practice of law but left the bar when war broke out with Mexico in 1846. He subsequently was chosen as colonel of the 3rd Regiment of Indiana Volunteers and distinguished himself at the Battle of Buena Vista.

After the war ended, Lane went into politics. Service as lieutenant governor of Indiana was followed by one term in Congress. When his term was up, he moved to the Kansas Territory in 1855.

In the U.S. Congress, Lane voted for the Kansas-Nebraska Act, a law that established Kansas and Nebraska as territories with the prospect of future statehood. This 1854 act superseded the Missouri Compromise of 1820, which admitted Missouri as a slave state while creating no new slave states farther north than the southern boundary of Missouri. Kansas and Nebraska were north of that line, but now by the doctrine of popular sovereignty, citizens of the territories would decide whether to allow slavery when they were admitted to the Union.

Large numbers of settlers poured into Kansas, some intent on turning it into a new slave state and others who supported the Free State cause. Previously in politics, Lane had shown little interest in slavery or abolition. In Kansas, he saw the prevailing political consensus was anti-slavery, and he threw himself wholeheartedly into the Free State cause.

A flood of new arrivals from nearby Missouri tipped the first Kansas elections toward a pro-slavery territorial government. By 1856, anti-slavery men were again the majority in Kansas. Led by Lane, they met at Topeka and established a parallel Free State territorial government. They chose Charles Robinson as their governor and picked Lane to represent the territory in Congress. The federal government recognized only the original pro-slavery territorial administration, so Lane remained in Kansas.

Violence flared in Kansas as pro-slavery Missourians called Border Ruffians clashed with armed Free State adherents called Jayhawkers. Border Ruffians sacked the Free State town of Lawrence in May 1856. In retaliation, abolitionist John Brown and his men rode to Pottawatomie Creek and, using swords, killed five pro-slavery settlers. More acts of revenge followed, and about 50 people were killed as stories and illustrations of the fighting in “Bleeding Kansas” were splashed across the nation’s newspapers.

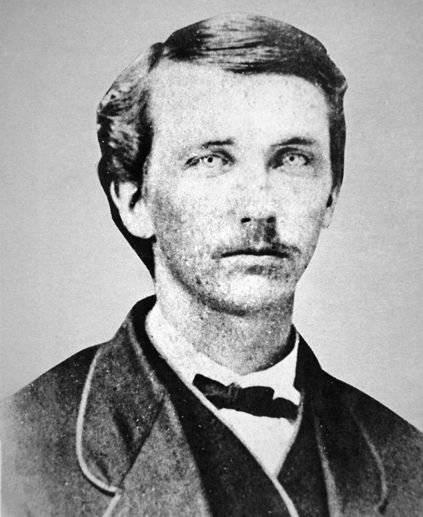

The Free State legislature appointed Lane a major general of militia, but his primary place was at the forefront of Free State politics. He was a remarkable orator, captivating crowds with his antislavery speeches. Over six feet in height, with gaunt, sharp features, Lane was called the “Grim Chieftain.” He seemed to care little about his appearance. Even when later posing for photos at Matthew Brady’s studio, he looked unshaven and disheveled, with his hair wildly awry.

In 1861, Kansas joined the Union as a free state. As one of the Free State movement’s most prominent leaders, Lane earned both the permanent hatred of the pro-slavery faction and a spot as one of the first U.S. senators from Kansas.

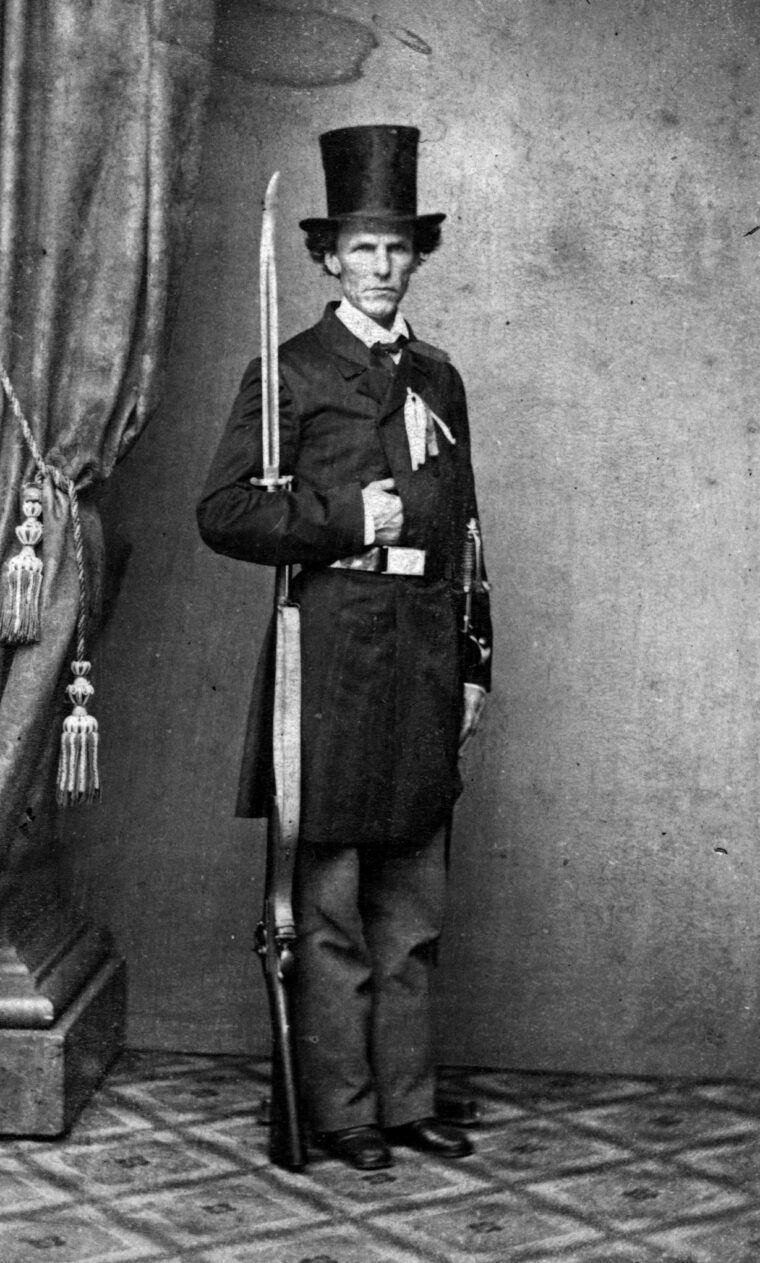

When the American Civil War broke out in April 1861, Lane was in Washington. In the early days of the war, the small regular U.S. Army was widely scattered at distant postings. No troops were on hand to defend the District of Columbia. Senator Lane rounded up more than 100 men for an emergency volunteer company. Most of his men hailed from Kansas or elsewhere in the West, so they dubbed themselves the Frontier Guard. Hastily outfitted with new muskets, they wore their own civilian clothing. Lane’s men drilled under the glittering chandeliers of their quarters in the East Room and stood picket duty around the White House.

By the end of April, several regiments of state troops reached Washington, and the Frontier Guards were no longer needed. Lane stood out as a reliable man of action amid the chaos and uncertainty of the first few months of the new administration and, on June 20, 1861, U.S. President Abraham Lincoln appointed Lane a brigadier general of volunteers, authorizing him to raise troops in Kansas. “I think two regiments better than three, but as to this I am not particular,” wrote Lincoln, who held Lane in high regard.

Lane soon returned to the West and established Lane’s Kansas Brigade, a unit that would eventually include several partially completed regiments. The regimental commanders were well known to Lane from prewar Kansas politics. Colonel James Montgomery, a militia officer during the border wars, headed the 3rd Kansas. Colonel William Weer, a former territorial attorney general, commanded the 4th Kansas, and Colonel Hamilton P. Johnson, a member of a state constitutional convention, commanded the 5th Kansas.

The first three regiments of Lane’s brigade were intended to include infantry and cavalry, each with an attached battery of artillery. The 6th Kansas and 7th Kansas, which were entirely of cavalry, joined the brigade later.

On the other side of the Kansas border, Confederate Brig. Gen. Sterling Price commanded an army of secessionist militia, the Missouri State Guard. On August 10, 1861, Price defeated Union forces under Brig. Gen. Nathaniel Lyon at Wilson’s Creek in southwestern Missouri. With 6,000 men, Price had an open path to clear Union forces out of Missouri’s western counties.

With Price on the move, Lane left Fort Leavenworth for Fort Scott, which was now the key to southeastern Kansas. Although the U.S. Army had shut down its post there in 1853, it left behind a growing town. Fort Scott provided a launching point for moves against Rebels in Missouri or south into the Indian Territory, which came under Confederate control when the U.S. Army evacuated its posts there in April. Adding his partly recruited brigade to a few Kansas companies already on hand at Fort Scott, Lane soon had about 2,000 men. Many of them were former Jayhawkers.

Political divisions hampered the Union war effort in Kansas. Normally, a state governor would establish volunteer regiments and choose their field and staff officers. With Lincoln’s open-ended commission, Lane competed with Governor Robinson for new recruits. Both men could reward political allies with officer commissions.

In the late summer of 1861, Lane, who was certain that Price intended to attack Fort Scott, pleaded for reinforcements. Robinson believed that Lane was a greater danger to Kansas than the secessionists of Missouri. “Some parties are interested to have war on our border, and consequently may not be impartial in their reports,” the governor wrote Department of the West commander Maj. Gen. John C. Fremont on September 1. “What we have to fear is that Lane’s Brigade will get up a war by going over the line, committing depredations, and returning into our State. This course will force the secessionists to put down any force we have for our own protection, and in this they will be joined by almost all the Union men in Missouri.” He urged that Lane’s men be sent deep into Kansas away from the border.

Rebel troops crossed into Kansas and captured several dozen mules at one of Lane’s camps on September 1. With 600 men, Lane went in search of the Rebels. He decided to concentrate his remaining forces at Fort Lincoln. The remaining Union troops looted Fort Scott before abandoning the town.

A dozen miles east of Fort Scott at Dry Wood Creek, just inside Missouri, Lane caught up with the Rebels on September 2. Fighting began about 4 PM. A shot from one of the Union guns, under the command of Scottish-born Captain Thomas Moonlight of the 1st Kansas Battery, wrecked one of the Confederate cannons.

Heavily outnumbered, Lane withdrew after a two-hour clash. Five Union men were killed and six wounded. Because of the raid on the previous day, the clash at Dry Wood Creek was also known as the Battle of the Mules. In a paradoxical twist of fate, the Missourians were unable to pursue Lane’s men because heavy rains flooded Dry Wood Creek that evening. Price turned north toward Lexington, Missouri.

In a September 8 letter to Lane, the commander of Fort Leavenworth, Captain William Edgar Prince of the 1st U.S. Infantry, expressed the regular army’s concerns about the behavior of his troops: “I hope you will adopt early and active measures to crush out this marauding which is being enacted in Captain [Charles R.] Jennison’s name, as also yours, by a band of men representing themselves as belonging to your command,” wrote Prince.

Jennison, a veteran of the antebellum border war, would later rise to command the 7th Kansas Cavalry, known as Jennison’s Jawhawkers. Company K, which was filled with particularly ardent abolitionists, was commanded by Captain John Brown, Jr., son of the famous leader of the 1859 attack on the arsenal at Harpers Ferry. The regiment combined abolitionist zeal with looting and horse theft, so much so that a common joke had it that the pedigree of many a Kansas horse was “out of Missouri by Jennison.”

Lane left Fort Lincoln and moved into Missouri on September 10 with 1,200 infantry, 600 cavalry, and two guns. The Kansas Brigade was not really in pursuit of Price, but intended to punish the secessionists of the border country. Lane and his officers paid little heed to the admonishments in Prince’s letter. Reports of looting and arson followed in the path of the Kansas Brigade.

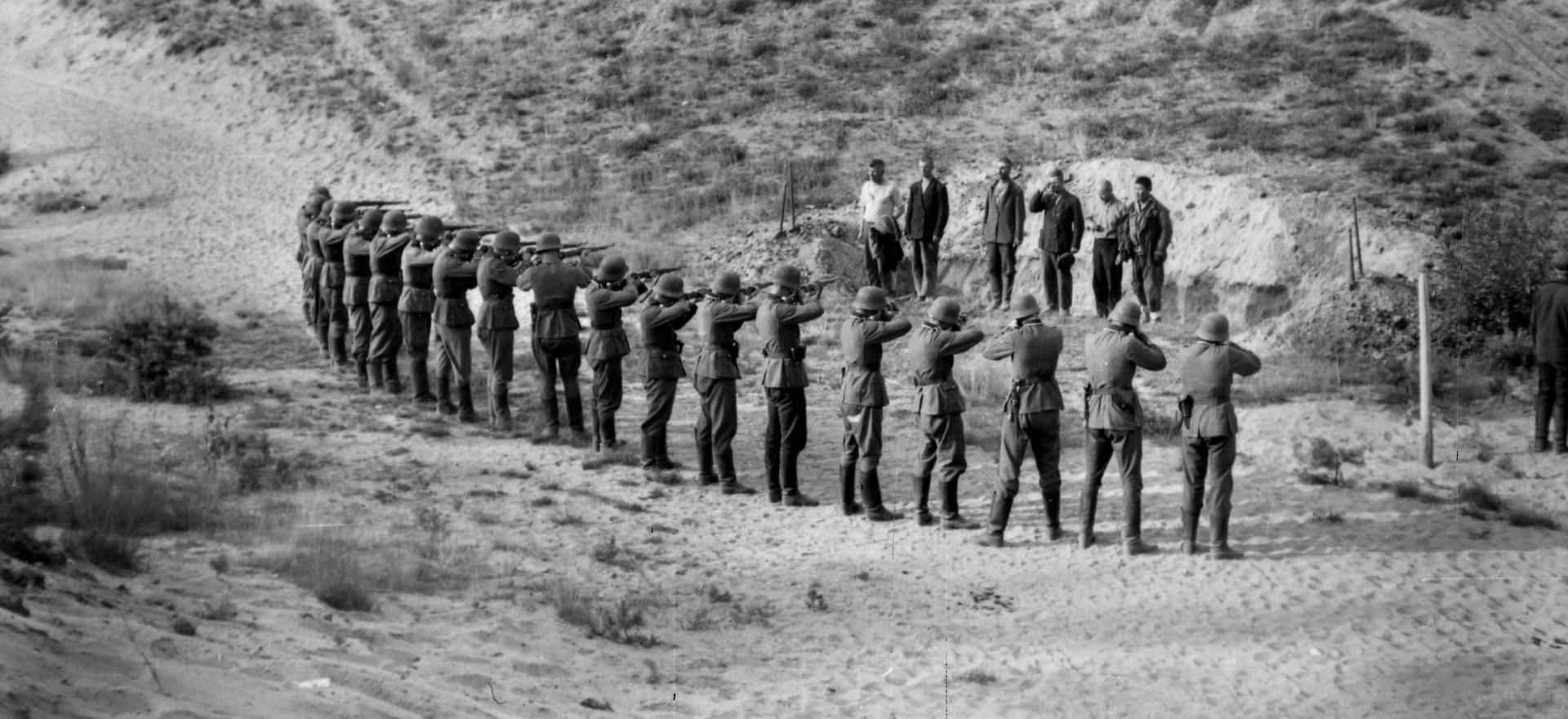

At Morristown, Missouri, on September 17, Colonel Johnson led an impulsive cavalry charge with the 5th Kansas. Just after uttering his last words, “Come on, boys,” Johnson was shot dead. Lt. Col. John Ritchie, a prewar abolitionist leader, replaced Johnson. After taking the town the Kansans arrested five citizens, tried them before a drumhead court-martial, and shot them.

On September 23, part of Lane’s expedition under Colonels Ritchie, Weer, and Montgomery captured the town of Osceola. Located at the head of navigation on the Osage River, the little town numbered 267 inhabitants in the 1860 Census. Osceola was the seat of St. Clair County. It was an odd coincidence that the county was named for General Arthur St. Clair, who was the grandfather of Lane’s wife Mary.

A handful of militia under Captain John M. Weidemeyer fired on the Unionists outside of town. In a short skirmish, the heavily outnumbered Rebels suffered several casualties before they were driven away.

Anger at enemy militia firing on them plus lingering resentment from the 1850s border war provoked a harsh fate for Osceola. Captain Moonlight bombarded the courthouse while the troops swept through the shops, stores, and homes. After carrying off what they wanted, the Kansas men set fire to the buildings including the home of Lane’s fellow U.S. Senator Waldo P. Johnson.

The raiders “destroyed fully 100 houses, the larger portion business houses of all kinds, stores, offices, etc.,” wrote Thomas D. Hicks, a witness to the damage. He recalled citizens later salvaging “salt, coffee, and many other articles … in a damaged condition” and finding amid the ashes nails “melted in masses.” In doomed warehouses and stores were hundreds of barrels of whiskey. Conscientious officers ordered their men to break open the barrels and pour out the contents. Some soldiers and civilians dipped containers into the streams of whiskey flowing from the smashed barrels. A rivulet of “whiskey on fire ran down a ravine 200 yards to the Osage River,” wrote Hicks. Some accounts claimed that the raiders drank so much stolen liquor that many of them could not sit their horses, and they left Osceola piled into wagons and carriages.

The sack of Osceola became an infamous landmark in the growing cycle of violence and retribution that engulfed the Civil War in Missouri. Primary sources regarding Osceola, as well as other events of the bitter warfare in Missouri, are highly partisan and often contradictory. Even the size of the town of Osceola is disputed. Secessionists estimated the population at up to 2,500, although the U.S. Census of 1860 counted 267 free inhabitants.

Pro-Confederate sources stated that the raiders arrested nine or more men, held a quick court-martial, and then shot them. Lane “murdered no person after capture [and] I never saw any abuse of women,” Hicks claimed. It seems no executions took place in Osceola, and these accusations were echoes of the very real shootings in Morristown.

Lane was actually several miles away from Osceola when his men hit the town. He tried to explain away the destruction. “The enemy ambushed the approaches to the town … and took refuge in the buildings of the town to annoy us,” wrote Lane. “We were compelled to shell them out, and in doing so the place was burned to ashes.” News of the looting and destruction alarmed Lane’s superiors and angered Missouri Rebels. More than ever, he was a marked man to the secessionists. Two years later, the destruction of Osceola would echo in one of the most infamous incidents of the Civil War.

With Lane’s help, Union forces tightened their control of western Missouri, but higher commanders saw a greater problem. Lane’s soldiers acted more like 1850s Jayhawkers than regular soldiers and seemed to eye every resident of Missouri as a rebellious traitor. Actually, Lane’s raids slashed through a region that still had many neutrals and loyal Unionists. Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck fretted that Lane and his uncontrollable men would make western Missouri “as Confederate as Eastern Virginia.”

Complaining of interference by Robinson and Union military commanders, Lane wrote Lincoln on October 9. He asked for 10,000 troops and command of a new military department consisting of Kansas, the Indian Territory, and part of Arkansas. Lane also stated that if given this assignment and freed from petty interference from government and military officials, he would resign his senate seat; if not, he would be compelled to give up his role in the army and return to politics.

A new Department of Kansas was created in November 1861. But, wary of Lane’s hatred of Missourians and the troubles caused by his undisciplined brigade, the army gave the departmental command to Maj. Gen. David Hunter.

Lincoln still supported Lane, but his status as brigadier general was in doubt because it was illegal for a sitting senator (or other civilian government official) to hold military rank. Governor Robinson believed that Lane was ineligible to remain in the Senate. For months, Lane tried to hold on to his senate seat and his general’s stars, even though Robinson tried to appoint a new senator in his place.

In January 1862 Lincoln chose Lane to lead an expedition into the Indian Territory. Lane squabbled with Hunter and refused to serve under him. Under pressure, Lane refused his general’s commission in a February 16, 1862, letter to Lincoln. He chose to remain in the Senate.

Lane’s Kansas Brigade was dissolved between February and April 1862. This was due in part to the brigade’s controversial and heavy-handed treatment of Missourians. “I will now keep them out of Missouri, or have them shot,” Halleck warned Washington of the Jayhawkers on March 25, 1862.

The unusual structure of Lane’s brigade did not fit the War Department’s model, so its units were broken up and reorganized as traditional regiments. Its infantry companies became the 10th Kansas Infantry, and the cavalry and artillery companies were transferred to regiments in their respective branches of the service. The new organizations were out of Lane’s control and, like other state volunteer regiments, under the governor of the state.

Even without a general’s commission, Lane still kept an active hand in the war. He pushed to raise the 1st Kansas Colored Volunteers, arguably the first regiment of African American troops in the Union Army. Their organization began at Fort Lincoln in August 1862. Although its 10 companies were not officially mustered in until early 1863, the regiment saw action at Island Mound, Missouri, on October 29, 1862.

Guerrilla units only loosely affiliated with the Confederate or Union armies committed atrocities that inflamed the war along the Kansas-Missouri border into an uncontrollably dark and vicious conflict. Most deadly of the guerrilla war’s raids was the destruction of Lawrence, Kansas, by 450 secessionist irregulars led by William Quantrill.

At dawn on August 21, 1863, Quantrill’s force rode into Lawrence intent on killing every man they found. Quantrill’s men specifically targeted Lane’s house. They found his bed warm but empty. The Grim Chieftain heard the spattering gunfire, the shouts, and the screams in time to slip out of his house. He hid in a cornfield while smoke rose from the burning town. The raiders left Lawrence in ruins and killed over 175 townsmen.

Fatally wounded near the end of the war, Quantrill reflected on the years of bitter fighting in Missouri and Kansas. A witness claimed that the dying Quantrill stated that if he had caught Lane at Lawrence he “would have burned him at the stake.”

Lane was reelected to the Senate early in 1865, but the end of the war brought him no peace. Shocking his political allies, he moderated his rhetoric and supported President Andrew Johnson’s mild policies toward the former slave states. Amid a rising chorus of anger at what many Kansas voters felt was a betrayal and rumors of financial malfeasance, Lane’s life fell apart. On a visit to Leavenworth on July 1, 1866, Lane put a gun to his head and pulled the trigger. Like his enemy Quantrill, he lived for several days before succumbing to his wound. Kansas journalist Milton W. Reynolds later summed up Lane as a “weird, mysterious and partially insane, partially inspired, and poetic character.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments