By Ray Allen Miller

I was raised on a farm between Hickory and Conover, North Carolina, the oldest of nine children, and this is a brief accounting of my military, combat, and prisoner of war experience in World War II.

I was one of the fortunate few who received more than the average amount of training time before being sent into combat. For this, I am very grateful. I feel that the extra preparedness made the difference in surviving or not surviving the horrors of war and the German prisons.

I am not writing because I think that my experience is unique or extraordinary in any way. I know that many combat soldiers and military service personnel suffered far worse experiences and for much longer duration than I did. However, this is my story, and if I don’t write about it, no one else will.

My grandfather, John Monroe Miller, fought for the Southern Confederacy during the Civil War. He was captured by the Yankees near Richmond, Virginia, and held prisoner for 16 months at Point Lookout, Maryland. I wish he had written an account of his combat and prisoner of war experiences. I am sure it would have given his descendents a better appreciation of the hardships that he and his comrades and their families at home suffered during that terrible and devastating war.

My military career began May 21, 1943, when I reported for induction at the courthouse in Newton, North Carolina. They took us by bus to Camp Croft, South Carolina, to be examined and assigned. We came back home for seven days, then reported to Fort Bragg, North Carolina. There we received our GI uniforms and equipment, and I was assigned to Battery C, 794th Antiaircraft Artillery, Automatic Weapons Battalion at Camp Stewart, Georgia. The camp was about 30 miles west of Savannah. My platoon sergeant was Sergeant Weakland, who was housed in our barracks, which was a simple wooden building. I have been told that he died in combat in France or Germany.

I had requested to be placed in the Army Air Corps since I had just left a job working in an aircraft factory. They assured me at the induction center that they would assign me to airplane-related work. Apparently, someone reasoned that shooting them down was somehow related. This was not exactly what I had in mind, so I started asking, “How do I get out of this outfit?” I was told the only options were to join the paratroopers or become an Air Corps cadet. I chose the latter and made application. Of course, I continued my training in the antiaircraft artillery and advanced in rank to private first class and then corporal.

Finally, on October 23, 1943, Hugh Horn and I received orders of transfer to the Army Air Corps for appointment as aviation cadets. We were transferred out of our C Battery and into post headquarters of Camp Stewart to await further orders. On November 20, 1943, we were ordered to Gulfport Field, Mississippi, for further tests, both mental and physical. After approximately 21/2 months we received assignments to Texas A&M College.

On January 1, 1944, we went to Texas A&M at Bryan, Texas. We were both assigned to the 308th College Training Detachment (Aircrew), Squadron 2, Flight B for a five-month college training course. I was training to be a fighter pilot.

After three months, however, the U.S. government saw fit to transfer air force cadets from schools all over the country back to ground forces. Our school was closed, and we were sent to the infantry. The need for men in the ground forces was greater. I don’t have to tell you, this was a sad day for hundreds of thousands of cadets all over the country.

On April 3, 1944, Hugh Horn and I, along with hundreds of students from A&M and other schools, were sent to Camp Van Dorn, Mississippi. There we became a part of the 63rd Infantry Division with the Blood and Fire patch. Most of the outfit was made up of non-commissioned officers, and we were given infantry basic training by a cadre of mostly pfcs. and privates. Our ranks meant nothing to them.

After one month of hard training in the hot sun, we were all split up and sent to different outfits. That is where Hugh and I parted company, and I was never to see him again. He did call me once at home in the late 1950s or early 1960s. He said he was a geologist, living in McComb, Mississippi. He didn’t seem very happy, and I never heard from him again.

I was assigned to Company M, 410th Infantry Regiment, 103rd Infantry Division at Camp Howze, in Gainesville, Texas. I started training all over again, beginning with basic training, and continued on through advanced training. This was the fourth time I had been through basic training. I was assigned the job of communications corporal since I already held the rank of corporal. My job was to establish telephone communication (by sound-powered phones with wires laid on the ground) from squads to company, to battalion headquarters, and whenever possible, to our backup artillery.

The exact date I joined the 410th Infantry is unknown, but it was approximately the middle of May 1944. We continued our training until the end of September and then left for Camp Shanks, New York, and the port of embarkation. This included the entire 103rd Division.

On October 6, 1944, our entire division set sail in a convoy of 14 ships to a destination unknown to us. Our 410th Regiment was aboard the transport USS Gen. J.R. Brooke, the flagship of the convoy. We were escorted by destroyer escorts to help protect us from attack by German submarines. Many troop ships and merchant ships had been lost to submarines. Our ship was a Kaiser-built Liberty Ship. After several days at sea, we encountered a terrible storm that lasted for days, and almost everyone was seasick. The first land we sighted was Southampton, England, where we stopped briefly but did not go ashore. We continued on to the Mediterranean Sea through the Straits of Gibraltar to southern France, and arrived at Marseilles on October 20.

The Allied invasion of Marseilles had been made in August, and the Germans left the city on August 25, 1944. The harbor was still in bad shape. They unloaded us with full field packs, weapons, and full duffle bags and marched us toward the staging area north of the city.

The staging area was only about 10 miles from the harbor, mostly uphill. We marched and we rested; we marched and we rested some more. We must have gone 20 miles, it seemed. Those duffle bags were heavy. It started getting dark, and finally our leaders admitted we were lost. They decided to wait until daylight, so we bedded down where we were. That night it rained a cold rain. Everything we had was wet. The next morning we found the way to the staging area, and we lived in pup tents in the cold rain and mud for two weeks. During this time the ships were being unloaded, the machinery and equipment reassembled, and plans made to engage the enemy. Some of us were sent to help unload the ships.

On November 1, 1944, we left Marseilles to go into combat. Some went by train; we went by truck to Dijon, France. We were led into the combat zone at night to relieve elements of the 3rd and 36th Divisions. We became a part of the VI Corps of the Seventh Army. At that time, and through most of our time in combat, we didn’t know where we were. We just went where they told us to and did what we were told to do.

The night we were led into combat, slipping and sliding, it snowed a couple of inches. When daylight came we saw dead bodies lying around —some German and some American soldiers. We were in the woods and were told the Germans were just across the draw from us. Everything was quiet, and the snow was so beautiful I suppose it was hard for the men to realize any danger.

Everyone got busy digging in and chopping wood to reinforce foxholes as though we would be spending the rest of the war in this spot. I ran telephones to most of the leaders’ positions. A couple of hours later the Germans zeroed in on us with their 88s [88mm artillery], and we sustained a number of casualties. One sergeant, who was a “gung-ho” squad leader back in the States, went berserk and had to be carried out kicking and screaming. He never returned to combat.

After we were able to get the Germans on the run, we attempted to keep them running, so as not to allow them time to set up their artillery or dig in. We were told to put all of our gear except the absolute essentials on trucks that they brought in, and we could pick it all up later, farther on up the line. We kept only shelter halves, raincoats, spare socks, felt insoles for our shoe packs, and our weapons. We were never to see the other stuff again.

We had been issued two-man pup tents when we first went into combat. Each man had a shelter half, a tent rope, a collapsible tent pole, and some pegs. Two men had to put their shelter halves together to make a pup tent. We learned early on the pup tents were not safe in combat after several of the soldiers awoke to find bullet holes in theirs. We did use the canvas shelter half to lie on the wet ground to sleep on, or to cover foxholes to keep the rain from spattering in our faces.

We had a lot of cold rain as we fought through the Vosges Mountains. Water would seep into our foxholes, so we would cut hemlock branches and put them in the bottom to hold us up out of the water. I often covered my foxhole with my raincoat, and the next morning there would be frost all over the underside of the raincoat. Later on in the winter the rain turned to snow and the ground was frozen, but it wasn’t so wet and sloppy.

We were kept on the run, week after week, chasing the Germans through the Vosges Mountains, taking one town after another. The artillery would usually shell the town, and the Air Force would do some bombing, then we would go in and finish cleaning it out.

The civilian residents of the towns would come out of hiding from the hills, or wherever, and welcome us with open arms—and open wine bottles—after the fighting was over. Many of the homes were still abandoned when we arrived at a newly liberated town. The first thing all the GIs wanted to do was to find a bed or someplace to lie down and sleep. Usually, however, we would no sooner get bedded down than an order would come for us to move on to the next town. We were so tired some would actually doze off while walking. I remember one time a German machine gun opened up on a column of men in front of us. We all hit the ground, and while a squad was dispatched to knock out the machine gun I went to sleep lying there in the mud and cold rain.

Once while in the combat zone, we got to exchange our clothes for some that had been laundered but not pressed. At least they smelled better.

Often, we would be in combat positions where the cooks could not come near us with their vehicles to deliver our rations. Sometimes I would go back to battalion headquarters after food for our platoon. Our food while in combat was mostly K rations. The K rations were in flat cardboard boxes with heavily waxed wrapping to make them waterproof. The boxes were small enough that you could carry enough in your field pack for two or three days.

The K ration was condensed and highly concentrated in nutrition. It contained a daily chocolate bar (called a D bar), a daily cigarette ration, and a small can of food. They had hardtack crackers to eat with the canned meats. There were three different menus: breakfast, lunch, and dinner. Breakfast was chopped ham and egg. One meal was corned beef hash, and I don’t remember what the other was. The cigarette ration was responsible for a lot of men starting to smoke for the first time.

About Christmastime 1944, our battalion took a short rest (about a week) at some French town. We found an old radio and hooked it up to a Jeep battery. I ran an antenna wire out, and we got some American music on it. It really sounded good to us, even though we had to strain our ears to hear it.

Our platoon sergeant, Joe Rivers, came out of hiding during this rest period and started his old “spit and polish” routine. While in combat he was to be found the farthest back in the deepest foxhole and was not worth a pinch of pudding. He was an old career man and was scared to death in combat. I voluntarily took over his duties during combat, and our lieutenant was attempting to get me promoted to his master sergeant rank.

After our short rest the 410th returned to the front, and we pushed on across the German border and into the famed Siegfried Line in some of the most rugged mountains I have ever seen. The Siegfried Line ran along the German border next to France. It was a wide band of heavily reinforced and interconnecting fortresses, or pillboxes, tunnels, etc. I can remember going inside some of the pillboxes.

We were still fighting within the Siegfried Line, making painfully slow progress, when the Germans launched their last, desperate but massive counteroffensive. Our outfit was ordered to withdraw to the VI Corps middle line of defense along the Moder River on January 19, 1945. We withdrew under the cover of darkness and in severe winter weather. We arrived at Mulhouse, France, on January 24 and occupied the town. The Germans followed close behind us and began shelling the town. The 410th moved out to positions on a hillside overlooking the town on the west side. We were greatly outnumbered and spread much too thinly.

As we moved out of Mulhouse, the Germans moved in, and we were sitting ducks for them in our position. We were on a bald hillside with no trees or cover of any kind. We dug in as best we could to escape the scorching small arms fire. Eight of us were holed up in a potato cellar. Several men down below us were hit. We did not know how badly they were wounded. We were pinned down so completely that we couldn’t stick a finger up without getting it shot off.

When darkness came, I found my way back to our battalion headquarters and brought medics with stretchers to check on the wounded and try to get them out. The medics slipped down to the wounded men and found one was dead. The others they took back to the battalion aid station. I stayed with the other seven men in the potato cellar that night.

When daylight came we saw Germans dressed in white riding up and down the road in American Jeeps in back of our lines. They had infiltrated our lines and had overrun battalion headquarters behind us. We were cut off from the rest of our outfit, but the Germans had not bothered to capture us. We didn’t know where any of the rest of the company was, except the eight of us who were together. We decided to split up into two groups and try to make it back to our outfit.

Our second lieutenant, Walton Lamkin, and three others, whose names I don’t remember, went first. Of course, we didn’t know then, but they made it back okay. Shortly after they left, Richard Scally, Todd Klabaca, Ernest McIntyre, and I took off in the bitter cold and knee-deep snow. We headed in the direction we thought our outfit might be. Several German soldiers came along the road and passed right by us but paid us no attention. We had a long way to go across open fields without cover of woods or anything. In the snow we were perfect targets. We could hear slower firing American machine guns in the distance, so we decided to head in that direction.

As we crossed the tree-lined road that headed west out of Mulhouse, we suddenly came upon a lone German soldier driving a donkey cart with a load of mortar ammunition. He quickly threw up his hands and begged, “Don’t shoot!” so we took him with us as our prisoner. We just left the donkey there on the road and headed out across a large, open field of snow. There was no other choice. German soldiers were traveling freely up and down the road. We just hoped we wouldn’t be noticed.

We had only gotten about 100 yards from the road when we were suddenly fired upon by German soldiers from behind the trees at the road. We instinctively hit the ground, and when we did our prisoner grabbed the rifle of one of the men who was hit and covered us. The German soldiers from the road joined him, and they took us prisoner.

McIntyre and Klabaca were both hit. Mac’s lower leg was broken, and Todd had a bad wound in the thigh. Two or three shots later Mac was hit in the shoulder, as well. Neither of them was able to walk on their own. The German soldiers were going to kill them and leave them there because they were in a hurry to get out of that area. We begged the Germans not to shoot them and told them we would help them. Richard Scally and I, and our ex-prisoner, practically carried Mac and Todd the one kilometer back to the German aid station at Mulhouse, near both the German and Swiss borders.

We had been captured by the dreaded SS troops we had heard so many bad things about. But really they treated us pretty well, except for threatening to shoot our wounded buddies and prodding us along in the deep snow to hurry us.

The medics at the aid station gave us hot wine to drink and did a good job of first aid on the wounded. They put Todd and Mac each on a small sled and had us pull them back to the next town behind their lines. They put us in a large barn-like building with lots of other prisoners, probably a hundred or more. That night, a German ambulance came and took the wounded away. We never saw them again.

The next morning, January 26, 1945, they started marching us away in a column of fours. As we got a couple of hundred yards from the building our air force came over, and dive bombers bombed the building we had just vacated. It went up in splinters. Then they came back around for a strafing run on the column of men. Just about the time they got us in their sights, they apparently recognized us as American prisoners. They didn’t fire, pulled out of their dives and waggled their wings at us as they left. Man, you talk about sweating blood! Even the German guards broke and ran behind the trees that lined the road. Of course, they didn’t allow us to run.

They walked us for about seven days as far as we could walk each day. When night came they would find a barn or some similar shelter for us, and they would feed us. The food wasn’t great, but compared to what we had in store for us later it was a banquet. We had no idea where we were or where we were going.

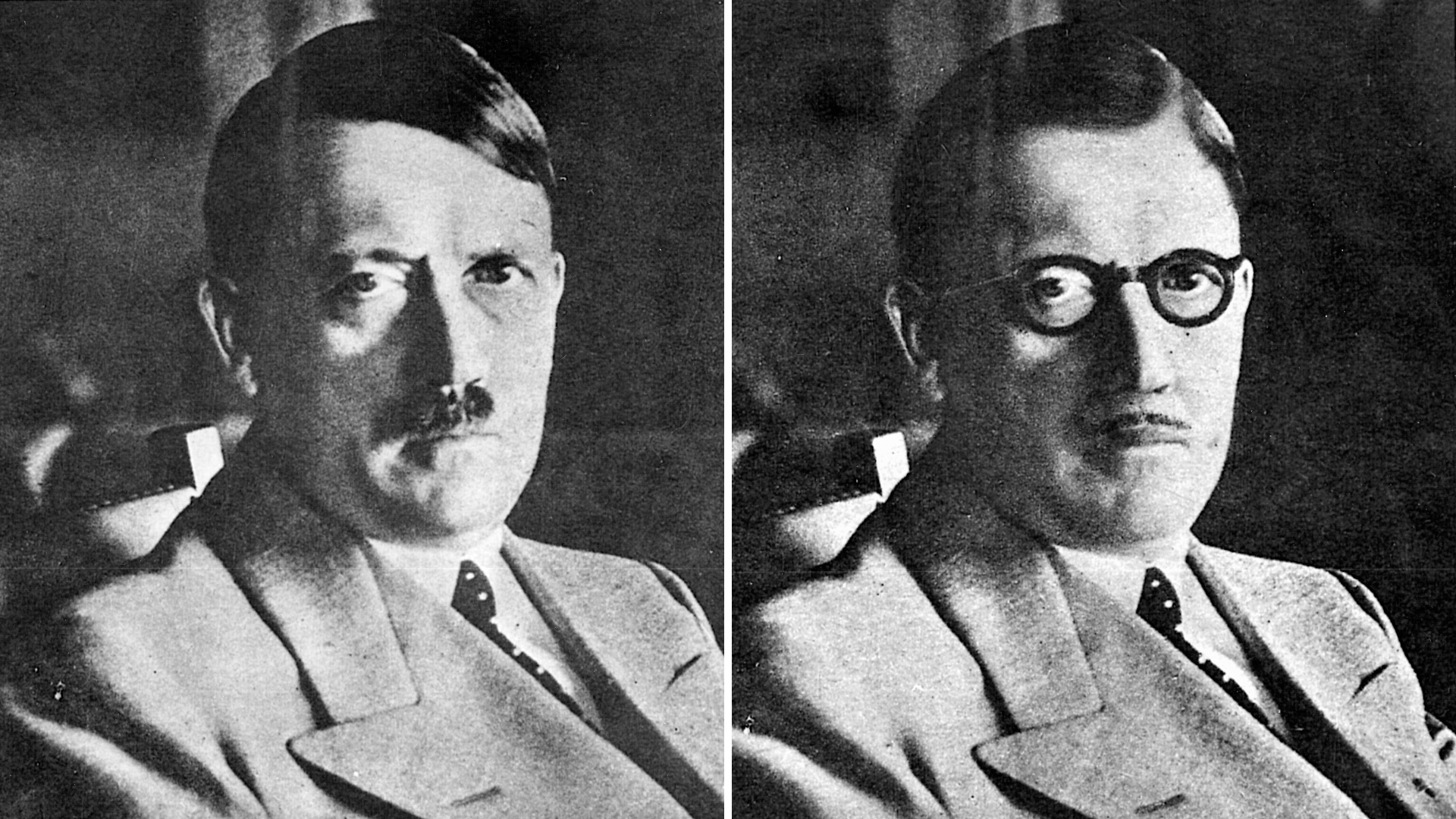

It was about February 2, 1945, when they got us far enough behind the lines of battle where they could operate trains. We were loaded into boxcars like animals and taken to Stalag XII-A at Limburg, Germany. I’m not sure how long we traveled by train, as my memory of that trip has diminished considerably over more than 50 years. I do remember the civilians giving us water, bread, and some turnips through the cracks in the boxcars when the guards weren’t looking. Some of the Germans spoke English and seemed eager to talk when the guards were looking the other way. They would say, “We are the good Germans. The Nazis are the bad ones.”

We arrived at Stalag XII-A on February 4. This I know for sure because I have it marked on my 1945 pocket calendar. On this calendar I have marked and noted all of the important events in my life for that year, beginning with January 25, when I was captured. I still have this calendar and have written an interpretation of all of the markings on it. A lot happened in my life that year.

The Germans marched us from the railroad into Stalag XII-A. We had a brief interrogation but nothing like we were expecting. I guess they figured they already knew more about us and our Army outfits than we did, so why waste their time. We still had all the clothes we were wearing at the time of capture and everything else except our weapons. They even let me keep a large pocketknife, a folding compact safety razor that fit into my watch pocket, a fountain pen, and my high school class ring. I also had some money hidden inside my socks that they never found. Really, they never searched us except for guns and large weapons. We were really fortunate to be able to keep our Army overcoats, else we would probably have frozen to death.

I was wearing thermal underwear, my ODs (olive drab wool pants and shirt), a wool sweater, an Eisenhower jacket (a short wool jacket designed for combat), snowpack boots, and wool socks. Snow packs were short boots with rubber feet and leather tops. They had half-inch thick changeable felt insoles. I also had lace-up leggings, a wool cap under my helmet liner, a steel helmet, and my long GI overcoat and wool gloves. We did not get to keep our helmets and helmet liners. Each GI was issued a spare set of insoles and a spare pair of socks. I carried my spare socks and insoles under my wool sweater, where they would dry from my body heat. The snow pack boots made your feet sweat, so I changed insoles and socks daily. You had to keep your feet dry to keep from getting frostbite. Many GIs lost toes and parts of their feet due to frostbite.

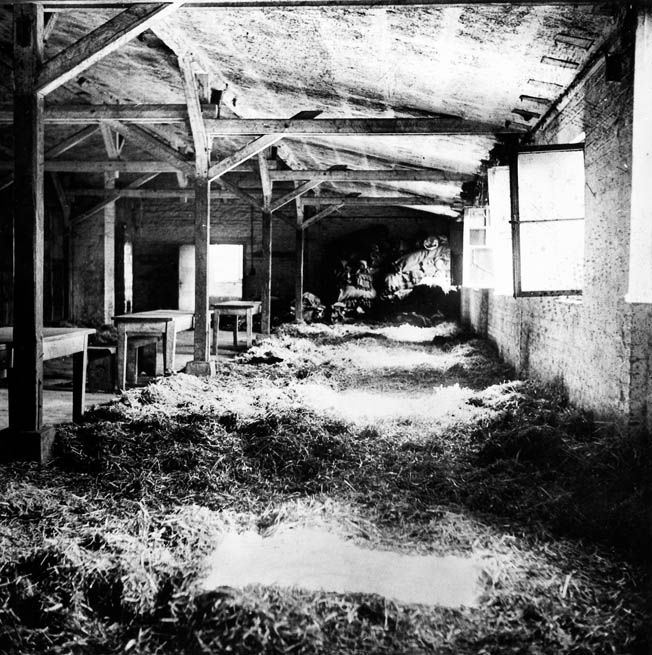

The Germans at XII-A assigned each of us a prisoner identification number. Mine was 96142. We were then assigned to our barracks. The barracks were unheated and had brick floors laid on the ground. For each two men there was a little bunch of well-worn straw on the floor for a bed. The straw was heavily infested with body lice. Each prisoner was issued a gray German blanket. The two men pooled their blankets together and slept in all their clothes and overcoats to keep from freezing to death. It was bitter cold outside with lots of snow, and I guess it was just about as cold inside. We lay down at night shivering and woke up shivering the next morning. Today, when we are having cold, snowy, and icy weather, I thank my God that I have a warm bed to sleep in and plenty to eat.

I can’t remember how many men occupied each barracks, but quite a few—maybe 50 or so. The latrine was in a building nearby. It consisted of several holes in the floor that you would squat over and a large tank underneath the floor to catch the waste. There was no toilet paper or anything else. A lot of the men used money for wiping paper. I was quite fortunate, I thought, because I found a piece of cardboard which I would separate into thin sheets and keep in my pockets until needed.

Each prisoner was issued a tin can to eat from. It was up to him to keep it clean if he could. The water was only turned on a couple of hours a day, and it was ice cold. During this time we had to wash ourselves and our soup cans. After a few days, most of us were having stomach cramps and diarrhea.

Our food ration consisted of a can of imitation coffee in the morning, a can of “grass soup” in the afternoon, and a slice of hard bread about one inch thick daily. That was all. The grass soup, as we called it, was watery with something that resembled hedge clippings, and if you were lucky you might find a tiny bit of potato in it. The bread was brought to us in whole loaves, and it was our job to divide each loaf equally between five men. I’m not sure about the number of men each loaf served, but I’m thinking it was five.

We were divided into squads of five men, or whatever number, and the bread was delivered to the squad leader. I was appointed leader of my squad, and so it was my responsibility to slice the bread in equal portions. If there happened to be a piece that looked smaller than the others, that was always my piece. The reason I got the job of dividing the bread was that I was the only one who had a large pocketknife. The bread was hard and dry, and it looked like it was coated with sawdust. The knife made squeaking noises when you sliced it. Not a crumb was wasted. These men were hungry and irritable and would fight you over a crumb of bread.

Stalag XII-A was a large camp that was to be only a temporary home for us. It was a segregation center for prisoners of all nationalities and ranks. Prisoners were segregated according to rank and the language they spoke. Commissioned officers were sent to officer’s camps, most soldiers with rank less than corporal were sent to labor camps. Noncommissioned officers, for the most part, were sent to camps where they were not required to work. Of course, there were exceptions.

None of us were required to work while at XII-A except for one day when we were taken to help unload Red Cross food parcels. We had to carry them from the railroad to a warehouse. I don’t know who benefited from the parcels, but we never got any of them while we were there. Some of the guys tried to break open parcels while the guards were not looking, but most were unsuccessful. The guards would yell at you, hit you with their rifles, and threaten to shoot you if you were caught.

The prison camp had been hit by a British bomber several weeks before we arrived, and some of the prisoners were killed.

The diarrhea or dysentery took hold of us quickly and fiercely. Most of us also developed urinary and kidney infections. Most had little control of bowel movements or urination. Many were passing blood through both. It is unbelievable how fast a healthy man can deteriorate under these conditions. I was only there for one month, and I lost an estimated 60 pounds. Many of those who came in the same time I did never made it out alive. The dysentery and starvation would weaken them so much that pneumonia would come along and finish them off. Those who were wounded when they came in stood little chance of survival.

The camp had two doctors who were prisoners, one American and one British, but they had no medical supplies. The worst cases were taken to them at the hospital. The hospital also had bed of straw, which crawled with body lice. Nobody ever came back from the hospital that I knew of. We were told that an average of seven prisoners died each day in this camp. The bodies were probably buried in mass graves.

The body lice were about the size of small ants. They were in our clothing, our bedding, on us, and everywhere. The Germans offered nothing to exterminate them. They made no visible bites on us, but they must have been sucking body fluids somehow. You could feel them crawling on you and scrambling and clawing to get through spots where your clothing fit tight. They laid thousands of eggs in the seams of your clothing. We would take off our clothes a piece at a time, scratch off the eggs, and then put that piece back on and take off another. This gave us something to do to pass the time.

We also talked a lot about food. I think half the guys in prison had plans to go into the restaurant business or open a hamburger stand. You could hear all kinds scrumptious recipes discussed. Some tried to list all the different candy bars they had ever known. Everything the men thought about was food oriented, as opposed to back in the States when it was women oriented. These were some of the things we did to pass the time and to take our minds at least temporarily off our difficult situation.

On the first day we came to XII-A, we were allowed to address a card to our next of kin stating that we were prisoners of the Germans and that we were okay. My parents received my card sometime after I was liberated. That was the only time I was allowed to send any mail, and I never received any while I was a prisoner. My parents were notified that I was missing in action, and they didn’t know if I was dead or alive until April 25, 1945, when they received a telegram telling them I was a prisoner of the Germans. Three days later, on April 28, 1945, I was liberated, and I wrote to them as quickly as I could. In those days you couldn’t just get on the phone and call home. My parents didn’t have a telephone, nor did any of our neighbors.

We had some men in our barracks who just gave up. They didn’t believe they would survive, so they just sat down to die. They wouldn’t eat; they wouldn’t talk; they wouldn’t wash themselves or exercise or anything. We just had to get them up, make them walk and wash up, and tried to encourage them as best we could. We were able to get a few of them to snap out of it. I remember at least one man who suddenly went berserk and was screaming and kicking. They had to restrain him, and he was taken to the hospital. That was the last we saw of him.

Most of the guards at the prison camps were older men who were too old for combat duty, and a lot of them were rather crabby. They would have us fall out and line up twice a day so they could count us. The prisoners were always doing things to irritate the guards, just to hear them scream at us. Some of the guards seemed a little dense. As they were trying to count the men, some would keep switching places in line so they would be counted twice. When the count didn’t come out right they would do it all over again.

I can still see the globs of yellow mucous all over the white snow where the men stood while being counted. Most of us had bad colds and bronchial congestion, or worse, and were coughing up a lot of stuff.

Stalag XII-A at Limburg was, without a doubt, the worst of my experiences as a prisoner of war.

On March 7, 1945, we were packed into boxcars again for a three-day trip to an unknown destination. We were given rations that were supposed to last us for the three days. Thanks to the U.S. Army Air Forces, the trip took seven days. We had more stopping time than we did traveling time. Once, because of the threat of heavy bombers, they unloaded us and took us into an underground bomb shelter. I do not know the location. Another time, American dive bombers started to strafe our train just as we were entering a long tunnel. The Germans pulled the train into the tunnel and stopped, and that is where we spent the next 24 hours in total darkness.

We wondered why our own air force would bomb a POW train. We wondered if our cars were marked. We later learned that our train was also pulling some flatcars with long-range artillery guns.

Several times, when the Germans knew the heavy bombers were coming, they would stop the train and run for safety away from the railroad. We prisoners, however, were locked inside the boxcars, sweating it out. We could hear the high-altitude bombers overhead, then the bombs screaming down. We knew their target was the railroad, and we prayed that, this time, they missed. We heard the explosions as the bombs touched down, and our boxcar rocked back and forth on the tracks. There were close ones, but we were still there, so I guess our prayers were answered.

We were packed tightly in the cars with not enough room for all to lie down on the floor without lying partly on top of each other. You would lie down and hope to get some sleep, and the next thing you knew there was a pair of legs across your body. The men were irritable and sick and cold, and there was lots of fussing and fighting because of the crowded conditions. Most of us still had dysentery and urinary problems, which added to the discomfort of the trip. Also, with all the weight loss my bony hips got rubbed sore from lying on the hard floor of the boxcar. There was a large can, about the size of a GI garbage can, in the middle of the car. That was our toilet, and they opened the car once a day to empty it. I’m just glad I wasn’t sleeping close to it.

On March 14, we arrived at Stalag 10-C, at Nienberg, Germany. One prisoner had died on the train during the trip. We were all starved because we had only brought food for a three-day trip, and we had been on the railroad seven days. When we got off the train, they took us first to what they said were gas chambers. They took us inside, a few men at a time, had us take off all our clothes, clipped off any hair we had anywhere on our bodies, and examined us closely for any signs of lice or eggs. Our clothes were run through a gas chamber or something that killed all the lice and eggs. I can’t remember whether we got to take a shower or not. Anyway, when we got our clothes back we were free of lice for good. That was the best thing the Germans ever did for me while I was a prisoner.

The food at this camp was much better and more adequate. We also received supplemental Red Cross parcels of food, candy, and cigarettes. The barracks were wood-frame buildings with weather boarding and wooden floors up off the ground. I don’t remember if they were heated in any way or not. I can’t remember any bunks either. I think we slept directly on the wood floors. That was an improvement over the damp, cold brick floors at Limburg. Sanitary conditions were much better here, and with the improved nutrition our dysentery soon subsided.

We learned how to make tin can stoves, with one can suspended inside another and holes punched at the right places to make them burn efficiently. We burned small sticks of wood in them, and they worked very well for cooking or heating food. We bought our wood from the Russian prisoners who lived on the other side of the fence from us. The Russians brought some of the wood in from outside the camp, but much of it came from boards they were ripping off their barracks when the guards were not looking.

Cigarettes were the medium of exchange in the prison camps. Money was no good. Everything was priced in cigarettes.

The Germans were taking the Russian prisoners out to the bombed-out cities to do cleanup work. While they were out, they would load their pockets with whatever food items they could find or steal and bring them back to sell to the Americans for cigarettes. Sometimes the Russians had food items, such as eggs or potatoes for sale.

The Germans did not allow trading between the Russian and American prisoners, so they had to slip and do it when the guards were not looking. The Russians wore long overcoats and would hide their wares inside the coats while they stood at the dividing fence. Then they would open their coat, showing what they had for sale and hold up their fingers to indicate how many cigarettes they wanted for it. If the American customer thought the price was too high, he would say “no” and hold up fingers to indicate how many cigarettes he was willing to pay. Sometimes they would haggle a while before a price was agreed upon.

They always stood far apart until the price was agreed on; then they would go quickly to the fence and make the trade while the guard was headed the other way. Once, a guard was trying to discourage trading and fired his rifle to scare away the traders. The bullet hit an American prisoner inside one of the barracks and killed him.

The Germans gave us a small ration of cigarettes, and we were getting cigarettes in our Red Cross parcels. I had quit smoking when I became a prisoner, so I was saving all my cigarettes to buy food and some wood. American cigarettes were much preferred by the Russians and the Germans because they were of so much better quality than any of the European brands.

The temptation was too great, even for the German guards. Some of them also got in on trading with the American prisoners. They too wore long overcoats with many pockets and could easily carry in eggs, potatoes. and even loaves of bread.

One particular German guard noticed my high school class ring with its ruby stone, and he wanted it. He offered me a loaf of bread for it, and I said, “No way; I don’t want to sell it.” A few days later he approached me again and offered more, and I turned him down. He kept offering more until he finally offered three loaves of bread, and I let him have it. Bread was still a scarce item in our diet, so I sold much of it to some of my fellow prisoners for money—French, German, or Russian.

I kept the money hidden inside my boots until we were liberated. When we got back to Belgium, just before boarding ship to go home, I exchanged all my foreign money for American dollars. I was carrying over $300 in my wallet when we boarded ship for the States. After several days at sea, someone lifted my wallet from under my pillow while I was sleeping. My wallet was found later, somewhere on the ship—without the money, of course.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt died while we were at Stalag 10-C, and the Germans celebrated. They said, “The war is over; the war is over!” It was practically over, all right, but not the way they had hoped.

We spent one month at Stalag 10-C. On April 14, 1945, we watched as the Germans brought in large numbers of political prisoners to this camp. There were hundreds and possibly thousands of them, and they were a pitiful sight. They were marched in columns of four. They all looked like walking skeletons with skin stretched over their bones. Many were trying to help others who were unable to walk alone. Some would fall down, and the guards hit them with rifles or kicked them to make them get back up.

As they passed near us, some American prisoners flipped cigarettes near them, and about four of them would make a dive for the same cigarette. Then the guards would swear at them and kick them. We didn’t know what the Germans did with these people. They were both men and women.

The next day, April 15, they marched us out of this camp, and we walked, all in the same day, to Oflag 10-B. My recollection of this camp is vague, but it was a prison camp for officers. I do recall that it was somewhat better then 10-C, and the food was better. For the first time since I was captured we started getting chunks of meat in our soup.

We got a report from stragglers who had been sick when we left 10-C and could not walk with us but joined us in the next couple of days. They told us the Germans turned machine guns on all those political prisoners and killed them.

We had known for some time that the Allied armies were getting closer and closer and were really putting a squeeze on the Germans. After about a week at this last camp (Oflag 10-B), many of our prison officials and guards fled. The rest stayed and became our prisoners.

The Americans were now in charge of the camp. I don’t know where they got it, but a huge United States flag was hoisted over the camp. Some of our people went into the fields, killed cattle for beef, and dug up potatoes from storage mounds. We were eating quite well when the British Army came along and “liberated” us on April 28, 1945.

The British took us away in trucks and set up an elaborate tent city somewhere nearby. They fed us six times daily with mini-meals. We weren’t allowed to eat a lot at a time because they said our stomachs would explode if we did, since they were shrunken from prolonged starvation and malnutrition. They also served us “tea and crumpets” every couple of hours.

While we were there shower facilities were set up so we could take baths. We were issued complete Government Issue of British Army uniforms, including shoes, socks, underwear, towels, shaving gear, shoe shine kits, mess kits, caps, jackets, everything except weapons. I suppose for a short while we were British soldiers. I still have and use my shoeshine brush.

Our hitch in the British Army lasted only five or six days. On May 4, the U.S. Army Air Forces brought in C-47 airplanes and flew us out of Germany to Brussels, Belgium, and we became good old Americans again. I can’t remember if we traded in our “Lymie” uniforms there, or if it was at Namur, where they took us the next day. It must have been at Namur, Belgium, where they processed us back in with the living, gave us a quickie physical, and put us back into American uniforms.

We all got to write letters home. I don’t remember if we got to write while we were with the British or not.

If we had only known then what we know now about POW-related disabilities and disability claims…. Many liberated POWs had problems and even injuries that were attributable to their experiences but hid them from the examining doctors if it was possible. All we were interested in was going home. We were afraid if we complained there would be further testing and possibly hospitalization before we could go home. None of us wanted that. But if it had gotten on our records at that time, the chances are there wouldn’t have been so many of us denied benefits later.

After our processing at Namur, we were taken to Camp Lucky Strike outside of Le Havre, France, to await passage on a ship to the United States There were several of these camps named after American cigarettes, Camp Camel, Camp Chesterfield, etc. We were there from May 7 through May 10, 1945. During our stay at Camp Lucky Strike the war in Europe ended, and we celebrated.

On May 11, we boarded ship for the United States. We had some good sailing much of the way and enjoyed the trip, even though we were crowded aboard. We were eating well, and they served us a lot of eggnog between meals. They were trying to fatten us up before we got home. Twenty-three days after we left France, we arrived in New York.

We docked on June 2 and went back to Camp Shanks. This was the same camp we had left on October 6, 1944. That was only eight months ago! It seemed like a lifetime. It sure was a good feeling to be back in the good old U.S. of A!

A couple of days later, I was given a 60-day furlough with orders to report to a redistribution station at Miami Beach, Florida, following my 60 days. I went home to Conover, North Carolina, to see my family and let them know I was okay.

On August 8, I reported to Miami Beach Army Ground and Service Forces Redistribution Center. While I was there the war with Japan ended.

On August 20, I was sent to Aberdeen Proving Ground, Maryland. While there and on pass to Baltimore, I met Vickie Gutherie, the girl who was to be my first wife. After two weeks, on September 4, I was transferred to Fort Bragg, North Carolina, and worked as a records clerk at post headquarters, processing service records of people to be discharged. While at Fort Bragg, I was at liberty to travel locally.

I was discharged on November 28, 1945. I went to work for a small furniture frame shop in nearby Oyama, North Carolina, owned by Owen Miller and Alvin Herman, through the rest of the year 1945.

For years after I got out of military service, I made no attempt to locate any of my Army or POW buddies. It wasn’t until I became involved with the American Ex-Prisoners of War organization that I found the address of Richard Scally in Detroit, Michigan, and contacted him. He had visited Todd Klabaca and Ernest McIntyre, and they were okay. Dick Scally had worked for the City of Detroit until retirement. We continued corresponding with each other until his death a few years ago. His niece wrote, telling me of his death. I cannot recall the names of any of the men I was in prison with except Scally, who was captured with me.

When I see someone throwing away or otherwise wasting food, I can’t help thinking how many prisoners that food would have fed. When it is cold and rainy, or snow and ice outside, I always remember those times in combat and prison camp, and I say a little prayer, “God, thank you for a warm place to sleep and plenty to eat.”

Ray Miller lived most of his life near where he grew up, in a home he built near Hickory, North Carolina, on land he had helped to farm as a boy. After early experience as a construction electrician he worked as an installation and maintenance electrician for 32 years at the General Electric-Hickory transformer factory that he helped start in the early 1950s.

After his retirement at age 62, Ray pursued an avid interest in genealogy—his own and that of his wife, Kathryn Echerd Miller. Together they were active in the local genealogical society. He helped initiate the Catawba County, North Carolina, chapter of the American Ex-POWs, and he was the founding chapter commander. He died in 1999, at age 75.

This article was submitted by Ray’s son and daughter-in-law, Allen and Sandra Miller of Hixson, Tennessee.

I’m glad I got to read this account of Ray Miller’s WW 2 service. Reading these articles keeps the memory of these men alive. Please, keep re-posting their stories.