By Charles Hilber

Standing 6 feet 2 inches tall with a fiery temper, English King Edward I was an imposing and intimidating figure. Born on June 17, 1239, to King Henry III and Eleanor of Provence, the sister-in-law of the King of France, Louis IX, he learned the art of war as a prince before William Wallace was born, fighting in the Second Barons’ War and on the Ninth Crusade. While in the Holy Land, Prince Edward personally killed a would-be assassin who crept into his tent at night. He left the Holy Land on September 24, 1272. Two months later, he arrived in Sicily to learn of his father’s death and his own immediate accession.

William Wallace was born on or about the same year that Prince Edward sailed back to England. Our earliest authority for his life is a rather long poem attributed to Blind Harry, who was associated with the court of James IV of Scotland. Harry claimed to have based his poem on a book by John Blair, a monk who became Wallace’s personal chaplain and was later commissioned to write a book of his life by Bishop Sinclair of Dunkeld. No copy of this book has ever been found. Wallace was an infant when Edward, having returned to England, invaded Wales in 1276.

During his conquest of Wales, Edward became familiar with the longbow and adopted it for use by his military forces. He knew that his mounted knights would be at a disadvantage fighting in the mountains and forests of Wales against the guerrilla tactics of his enemy, so he simply hired 9,000 Welsh mercenaries to augment his forces. After their defeat, those Welsh lords who were allowed to retain their lands now became feudatories of the king, who annexed what was left as his personal property.

On March 18, 1286, King Alexander III of Scotland fell from his horse in the dark and was found the next day with a broken neck. His granddaughter Margaret became heir to the Scottish throne. King Edward was quick to take advantage of the king-less Scots and negotiated the Treaty of Birgham, by terms of which Margaret would marry Edward II, but Scotland’s independence would be guaranteed.

Unfortunately for Scottish political stability, six-year-old Margaret fell ill and died in September 1290, leaving multiple adult contenders for the throne. To avoid the bloodshed of a civil war, the Scots asked Edward to arbitrate the succession. Happy to comply, he arrived in Scotland with an army in May 1291 and informed the Scots that only the feudal overlord, or Lord Paramount of Scotland, could decide the future of Scotland. Under threat of military intervention by the bellicose English king, the Scottish nobles, many of whom owned lands in England and wanted to keep them, gave in and paid homage to Edward.

One of those who did not submit was the father of William Wallace. An English knight named Fenwick is purported to have killed Wallace’s father and older brother Malcolm. Up to that time, Wallace had been studying for a career in the church, not unusual for a second son, who according to the rules of primogeniture would not inherit his father’s lands. Blind Harry’s epic poem narrates a series of encounters between the angry young Wallace, described as a tall and strong man, and various English antagonists, resulting in a rather large body count of dead Englishmen, one of whom was Fenwick. Wallace was declared an outlaw, which only encouraged him in his resistance to English domination.

After slightly more than a year of legal wrangling between 13 contenders for the throne of Scotland, in November 1292 Edward decided upon John Balliol, who paid homage to him. In 1293, Edward’s attention to Scottish affairs was diverted by problems with French King Philip IV, who had confiscated Gascony.

Edward summoned the Welsh and Scots to provide military service against Philip. The Welsh rebelled, and the English king spent 1295 reasserting his control over Wales. At the same time, the Scots forged an alliance with the Philip, and Balliol’s men raided the north of England. Wallace spent the year slaughtering English soldiers, alone or with a small band of followers, according to Blind Harry. The encounters occurred from Dundee to Air. Wallace conducted his sorties from the forests of Clyde and Methuen.

Having dealt with the Welsh, Edward invaded Scotland and in March 1296 attacked the rich port of Berwick on the east coast. The town was not strongly fortified, its defensive perimeter consisting of a ditch and stockade. The inhabitants had just repulsed the English fleet and were not afraid of Edward. “Some of them bared their breeches and reviled the king,” according to the Lanercost Chronicle. The disrespectful Scots improvised insulting songs that identified Edward as Longshanks. Edward already was unhappy about the defeat of his navy. He would not bear the insults of the town’s defenders and personally led the attack, leaping his warhorse over a low point in the wall. Then the slaughter began. For two days, Edward’s men sacked the town, killing most of the inhabitants. The king then paid a large number of men a penny a piece to bury the bodies, according to the chronicle.

While rebuilding Berwick, Edward received a message from Balliol renouncing his homage to the English king. “If he will not come to us, we will go to him,” said Edward. He then dispatched John de Warenne, 6th Earl of Surrey, to take the castle of Dunbar, about 30 miles to the northwest. The resulting Battle of Dunbar fought April 27, 1296, was a disaster for the Scots. The English cavalry killed hundreds of Scottish infantrymen, and approximately 100 nobles and knights were captured. Edward arrived the next day to accept the surrender of the castle.

John Balliol surrendered on July 2 and was publicly stripped of the insignia of kingship, leading to his unfortunate nickname, Toom Tabard (empty shirt). A month later he was sent to the Tower of London, and a month after that Edward returned to England. The king left Surrey as governor and Sir Hugh de Cressingham as treasurer of Scotland. But by spring 1297, Scotland was again embroiled in rebellion.

Sir Thomas Grey of Heaton “was left stripped for dead in the mellay when the English were defending themselves,” wrote his son, English chronicler Sir Thomas Grey, in the Scalacronica, of Wallace’s attack on Lanark. “The said Thomas lay all night naked between two burning houses which the Scots had set on fire, whereof the heat kept life in him.”

The elder Thomas Grey was rescued the next day, but the sheriff, Heselrig, was not so lucky. As the story goes, Wallace kicked in the door of the sheriff’s house, struck him on the head with his sword, and then killed his son and every Englishman in the town.

In May, Andrew Moray had raised the flag of revolt in the north, ambushing Sir William fitz Warin, constable of Urquhart Castle, and besieging the castle, eventually capturing it sometime that summer. At the beginning of July, the Scottish nobles drew up their army against the English at Irvine in the southwest of Scotland. Dissension in the Scottish ranks prevented a battle, and the Scottish nobles submitted to Edward. But operating independently of one another, Wallace and Moray controlled most of Scotland north of the River Forth. Edward sent Cressingham and Surrey against the Scots, and on August 24, 1297, left for the Continent to deal with Philip IV. Wallace sent a message to Moray, suggesting that they join forces.

At that time, knights on both sides were covered from head to toe in ring-mail, though by then they sported genouilleres, which were knee-guards of metal plate or boiled leather, and ailettes, which were small, variously shaped shields of the same materials, attached to the shoulders. The ailettes bore heraldic symbols and were probably used as a protection for the neck. A conical steel helm was supported by the knight’s shoulders, though some knights preferred a simple iron cap with greater visibility. They wore over their armor a surcoat of varied material, also covered with heraldic symbols.

Knights carried a slightly concave heater-shaped shield composed of layers of wood and leather, and for offense a variety of weapons including lance, sword, and mace. The horses of those who could afford such protection also were armored. Foot soldiers generally wore less body armor and did not wear mail leggings. They also wore a simple metal cap or kettle-hat with a wide brim. Foot soldiers were armed with spear, ax, mace, sling, or bow.

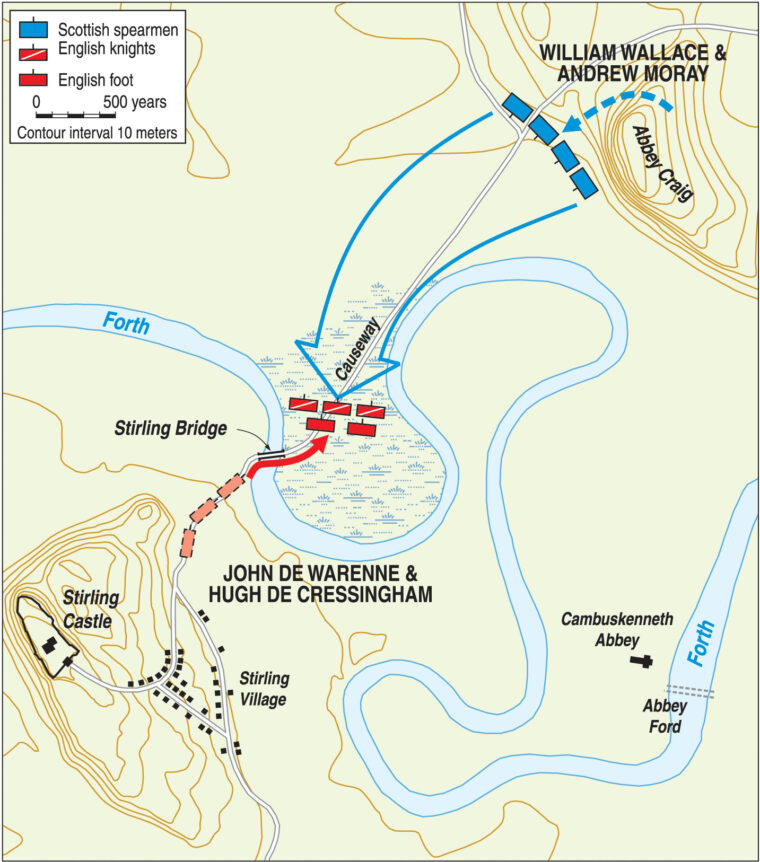

In September, both sides headed toward Stirling Castle and the strategic bridge that linked the northern and southern halves of Scotland. The fragile bridge was made of wood and only wide enough for two horsemen abreast. But above the bridge was an impassible swamp, and below it the water was deep and wide. About a mile upstream was a ford. The existence of the ford must have been known to Wallace and Moray, who chose to station their men on rising ground at the foot of the hill upon which stands Abbey Craig, a half-mile from the bridge. From the foot of the hill ran a raised causeway, not much wider that the bridge at which it had its terminus, the land on either side being muddy and swampy, passable perhaps by the Scots in their light mail shirts, but a potential morass for the heavily armored English knights on their heavy destriers. From the heights, Wallace and Moray observed the enemy in order to be able to react to a movement across the bridge or the ford.

Moray’s 5,000 infantry and 180 cavalry had joined Wallace’s 1,000 irregular troops. The English army was not much bigger, since Cressingham was known to be more parsimonious with respect to the kings’ money than the king himself, though he did not stint himself at the dinner table. For his greed and grasping ways, the rather obese Cressingham was absolutely loathed by the Scots and not especially well liked by his countrymen. Restricted by Cressingham’s financial constraints, the English probably fielded about 6,000 infantry, including 400 Welsh archers and 300 cavalry in the field.

Most of the English army arrived at Stirling late in the day on September 9, the baggage train lagging behind. James the Steward and Malcolm, Earl of Lennox, who had both submitted to Edward, arrived and offered their services as mediators to Surrey. On the following day, they rode over to the Scottish position, where their offer of peace was refused. That afternoon the baggage train and rear guard arrived with messengers from Sir Henry Percy and Sir Robert Clifford offering reinforcements. Cressingham, wishing to avoid the expense of paying any more men, sent them back with word for Percy and Clifford to disband their force.

On the morning of September 11, 1297, “5,000 of our men and many of the Welsh crossed the bridge and returned again,” according to chronicler Walter of Guisborough. The reason given was that Surrey was sleeping late. Although Surrey was in his mid-60s and hated being in Scotland, it is more likely that he was indeed awake and sent only a few men across the bridge to examine the structure and the ground beyond, upon which they might have to fight.

Around that time, James the Steward and the Earl of Lennox arrived with only a few armed men, not the 40 mounted men they had pledged the day before. It must have been obvious to Surrey that they had probably not made much effort to raise the promised contingent, but 40 cavalry would have made a formidable addition to his force. Without the added strength of a substantial body of reinforcements, Surrey perhaps thought that it might be prudent to try one last attempt at negotiating a peace.

Two Dominican brothers were sent to the hill to negotiate the surrender of the Scots. Moray, rather than Wallace, was most likely in command of the Scots, for he had more men and more experience with respect to organized warfare. What is more, he had taken several castles in the north of Scotland. In contrast, Wallace and his men had been a guerrilla band, specializing in ambushes and raids, suddenly attacking and then disappearing into wooded areas before the English could strike back. The Scots rebuffed the invitation to negotiate.

“Go back and tell your men that we come not for the good of peace, but we are ready to fight to defend ourselves and free our realm!” wrote Walter of Guisborough. “Therefore, let them advance when they wish, and they will find us ready to fight them even into their beards!”

Was it Wallace or Moray who uttered these defiant words? The death of Moray not long after the battle would leave his army and his legacy in the hands of Wallace, whose stature would assume legendary proportions over the following centuries, while the deeds of Moray were largely forgotten.

When the Dominicans returned with the Scots’ reply, some of the English knights were for an immediate advance. Others suggested careful deliberation. Richard Lundy, a Scottish knight, who, apparently disgusted at his countrymen’s lack of resolve at Irvine, had joined the English then and there, offered sound advice: “My lords, if we ascend the bridge, we are dead men; we can only cross two-by-two, and the enemy are on our flank.”

Did Lundy anticipate a flanking maneuver by the Scots designed to turn the English left, which, once they had crossed the bridge and formed up facing the Scots, would be unprotected by any natural barrier, while the English right would rest on a bend of the river? Or, did he have an informant among the Scots, who had divulged to him their plan of attack?

Lundy offered to lead a small group of cavalry and infantry across the ford and get behind the enemy, thus outflanking the Scots while they were trying to outflank the English. Lundy’s plan was rejected by those who thought that dividing the army would weaken it. The war council continued until Cressingham, perhaps considering that time is money, ended the debate. “It doesn’t help … to prolong the business further and to spend the treasure of the king in vain, but let us go up and let us fulfill our obligation as we are pledged,” he said.

Surrey must have reviewed his options in view of what had gone before. English knights at Dunbar had ridden down a disorganized mass of Scottish horse and foot, and at Irvine the Scots had capitulated before a blow had been struck. How could they stand up to the same English knights who had whipped them soundly in one battle and intimidated them into surrender before another? Who would expect them to show fight after that?

“The army of the Scots … lay hidden on a high part of the mountain,” wrote Walter of Guisborough. Although he knew the Scots were there, Surrey might not have been able to see them. In light of the previous encounters and putting no stock in the Scots’ tactical ability, he must have supposed that his army had plenty of time to cross the bridge and assume battle formation before the Scots could mount an organized offensive. Even if they moved before he was ready, the English knights would ride them down, as they had done at Dunbar. Surrey ordered Cressingham to lead the vanguard over the bridge. What happened next was probably related to Walter of Guisborough by one of the participants whom the chronicler names “that most vigorous knight, Lord Mameducus de Tweng.”

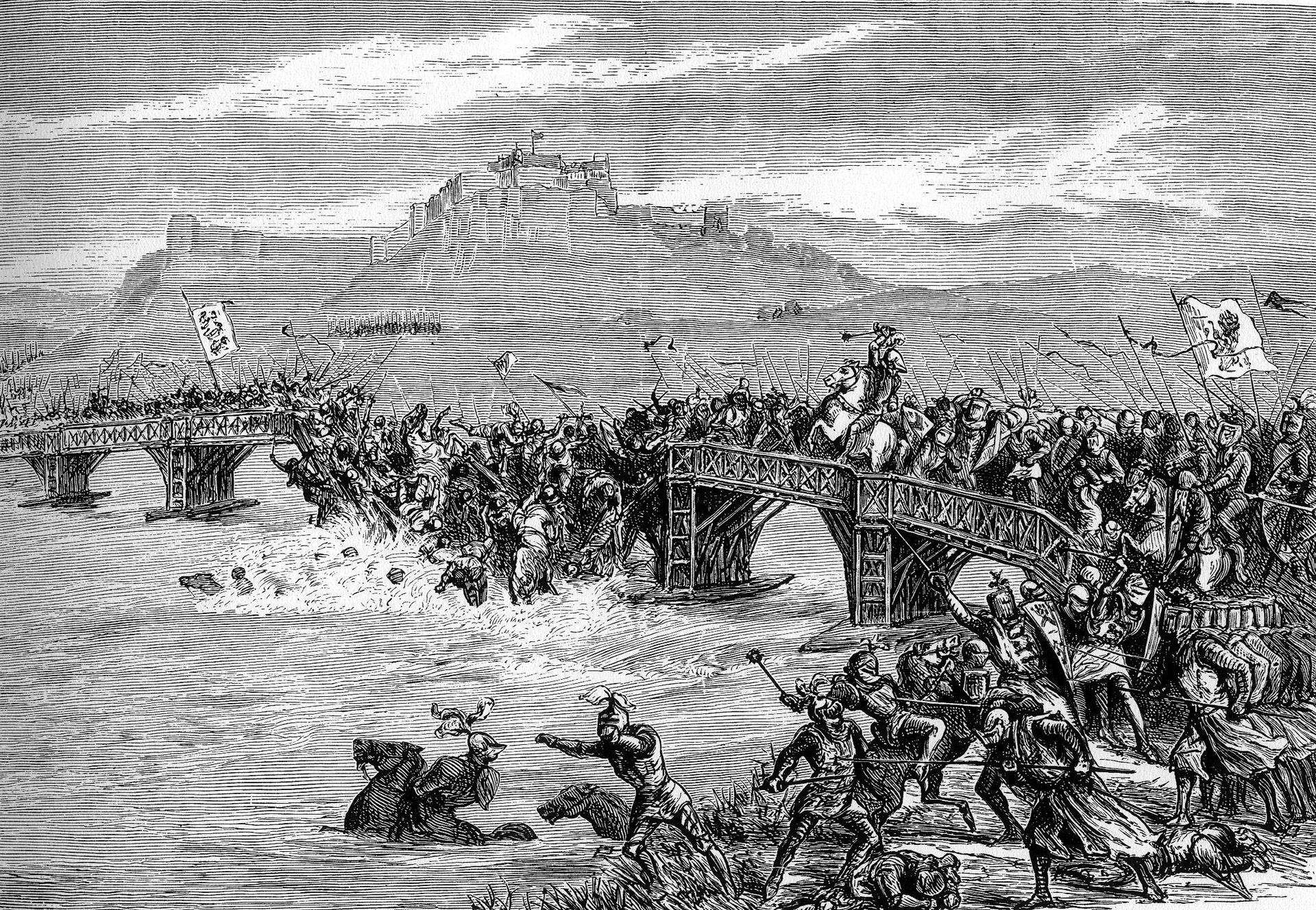

The English knights and mounted men-at-arms clattered over the bridge, led by Tweng and Cressingham and flying the battle flags of the King Edward and Surrey. At the site of the bridge, the river flows in a huge meander bend, the narrow neck of which is about 450 yards across. Through the low-lying land inside the bend ran the causeway to Abbey Craig. The 150 or so English knights must have followed the causeway to the point where it abutted the downstream loop of the bend, at which point they probably formed line to their left, most likely a single rank in open order, which would have given their line a frontage of 300 yards. Behind them, the infantry slowly filed over the bridge, marched up the causeway, and began to form line some yards behind the cavalry.

Moray and Wallace monitored the English deployment from the heights of the Abbey Craig . They could see the vanguard crossing the bridge and the middle guard and rear guard, two distinct formations of cavalry and infantry, lining up to follow. The Scottish infantry must have been deployed on the wooded lower slope of the Craig, possibly unseen but ready to advance at a moment’s notice. When most of the vanguard had crossed the bridge, the Scottish war horns sounded, and the Scots descended the mountain. The Scots were drawn up in four infantry phalanxes, called schiltrons, each six ranks deep, armed with 12-foot spears, held in both hands. To the English they must have appeared as a long line of pikemen, with a frontage close to 1,000 yards.

The English cavalry, remembering past victories and habitually contemptuous of foot soldiers, immediately charged the line of the Scots. They had less than a mile of ground to cover and the Scots were advancing as quickly as they could. Both sides crashed together; horses and men were spitted on the pikes. The English would lose about 100 mounted men that day, and many of those must have fallen at the first contact.

It may have been at this point that Cressingham was slain by the Scottish spearmen. It was a short, sharp fight, and then the surviving knights and men-at-arms recoiled from the Scottish spears. While this was happening, Lundy’s prediction became fact as the schiltrons of the Scottish right overlapped the English cavalry and wheeled toward the bridge. Walter of Guisborough’s chronicle seems to imply that a special force of spearmen, perhaps the schiltron or a smaller formation on the far right of the Scots’ line, had been designated to take the northern end of the bridge. “With spearmen sent, they occupied the foot of the bridge,” states the chronicle. Was this formation composed of Wallace’s lightly armored guerrillas, chosen for their ability to move more quickly than their more heavily armored counterparts, and led by the hero himself?

Seeing most of their cavalry down and themselves outnumbered three to one by the relentlessly advancing phalanx of pikes, the English line of foot disintegrated in a mad rush for the bridge. Blind Harry’s account of the battle, heroically legendary as it may be, supports this: “The South’ron’s Front … Did neither stand, nor fairly Foot the Score, But did retire, Five Aiker breadth and more.” As the English broke ranks to run for their lives, the Scots broke ranks to pursue. Only the company tasked with the capture of the bridge maintained its formation while it bore down on its target.

As the disorganized Scots merged bloodily with the fleeing English, the battle became a melee. Men alone or in small groups fought hand to hand for survival. Some of the Scots discarded their long pikes and swung battle axes. In the midst of this raging mob of shouting, screaming combatants, Tweng and two companions, caught up in the retreat toward the bridge, looked back and “saw that many of our men and the standard bearers of the king and count had fallen, and they said, ‘already the road to the bridge is closed to us, and we are cut off from our people,” wrote Walter of Guisborough. “At this, that most vigorous man Marmaducus [said], ‘you follow me … I will make a way for you as far as the bridge.’”

Marmaducus was “powerful in physical strength and of a lofty stature,” according to Walter of Guisborough. He was covered head to foot in expensive armor, his horse was probably also barded, and being a big man, he perhaps preferred a hand-and-a-half sword.

The bridge was now crowded and congested with a shoving, heaving mass of men and horses, those of the vanguard, fleeing the Scots, crashing into those of the middle guard, already on the bridge and being pushed forward by the ranks behind them. Men were falling and jumping from the bridge. The Scots assigned to capture the bridge smashed into the backs of the routed vanguard. With no room for them on the bridge and the sharp spears of the Scots piercing them from behind, the English foot soldiers were pushed into the death trap formed by the loop of the Forth. The Scottish horse, probably originally formed up behind or on the right of their infantry, had joined the pursuit led by Moray.

Tweng, striking left and right, cut his way through the disorganized Scots, headed for the bridge. He fought his way across, cutting down his enemies and pushing his way through any English infantrymen who blocked his path. As he reached the other side, the bridge collapsed. Blind Harry attributes this to the machinations of Wallace, who had sabotaged the bridge days before the arrival of the English. It is possible that the wooden structure of the bridge simply gave way under the weight of so many armored men and horses. “Our Earl … when the Lord Marmaducus had returned to his own men, ordered the bridge to be broken and burned,” wrote Walter of Guisborough.

What was left of Surrey’s vanguard was now trapped. Some of those who were stranded on the far side crossed the river by swimming. In a feat of determination, one knight somehow managed to cross the river on an armored horse. Approximately 2,000 English soldiers were killed. When the Scots discovered Cressingham’s body, “the Scots flaying, divided amongst themselves the skin of this man in small parts,” wrote Walter of Guisborough. “William Wallace caused a broad strip to be taken from the head to the heel, to make therewith a baldrick for his sword,” adds the Lanercost Chronicle.

With the bridge down, Surrey wasted no time leaving the vicinity. Observing the English defeat, the Steward of the Scots and the Earl of Lennox returned to their men concealed in the woods. As Surrey and his knights rode as quickly as possible to Berwick, the Steward and the Earl of Lennox harried the slower moving infantry and baggage train, slaying many of the enemy and carrying away plunder in the process.

Surrey continued on to London, and the Scots, as the Lanercost Chronicle relates, “entered Berwick and put to death the few English that they found therein.” In October, Wallace savagely raided the north of England, and it was at this time that Wallace was knighted; popular legend has it that this ceremony was performed by Robert the Bruce. In November, Moray died of wounds received in the battle, and, perhaps a month later, Wallace was made Guardian of Scotland in the name of John Balliol.

By February 1298, Surrey was back on the Scottish border with an army. Meanwhile, Edward had reached an agreement with Philip IV and returned to England on March 14. “He called a parliament of his men at York on the Feast of Pentecostes [and] he sent a letter to the magnates of the Scots,” states Walter of Guisborough. These developments occurred in late May. The letter instructed the Scottish magnates to present themselves at the parliament or be considered public enemies.

When the Scottish nobles failed to show, Edward mustered his army at Roxborough on June 24. It was much larger than the army that had been defeated at Stirling. Although the primary source documents record impossibly large numbers of horse and foot, modern historians put the numbers at approximately 2,500 cavalry, 13,000 infantry (most of whom were Irish and Welsh), and 5,000 archers.

The English army advanced into Scotland. It found the majority of towns and villages destroyed and people unwilling to divulge the location of the Scottish army. King Edward stopped at Kirkliston and sent the Bishop of Durham to take Dirleton Castle and two other nearby castles, which were full of armed Scots and might thwart his line of march.

The bishop’s initial attack failed. The English were short of supplies, having no wood with which to build siege engines, and no food other than peas and beans in the fields. Johannes Marmaduk asked King Edward for his instructions.” According to Walter of Guisborough, the king told him: “Return and say to the Bishop that he is a man of piety … nevertheless in this business it is not right to exercise piety … you however are a merciless man, and before I disapproved your excessive cruelty … but now indeed, go, and exercise all your tyranny, and not indeed will I censure you, but I will praise you.” He further advised Marmaduk not to show his face “till those three castles are burning.”

It took the bishop one month to fulfill his task, but now the army had run low on supplies and contrary winds prevented resupply by the English fleet. However, a few ships did manage to make landfall and furnish 200 barrels of wine and a small amount of food. Edward immediately distributed the wine to his hungry troops.

Of course, violence followed as the Welsh foot quarreled with the English foot, killing 18 of them. When the English knights heard of this, they armed themselves and attacked the Welsh, killing 80 of them and driving the rest from camp. The next morning it was reported to Edward that the Welsh were considering changing sides and joining the Scots.

“Why care I if enemies are joined to enemies … in one day, we will punish both,” said Edward. If the Welsh longbow men had indeed gone over to the Scots, the outcome of the Battle of Falkirk might have been quite different, but the English king was paying them, and without recompense they would be in the midst of an alien land, facing an uncertain fate, so, keeping a safe distance, they remained in Edward’s service.

On July 20, with the army starving, Edward decided to retreat to Edinburgh to await the supply ships. Before the army could march off, on the morning of the very next day, two Scottish nobles rode into camp. They informed the king that the Scots were within six leagues of Edward’s army near Falkirk. “When they heard that you planned to return to Edinburgh, immediately decided to follow you and to attack your camp the following night,” wrote Walter of Guisborough. To that Edward said, “It will not be necessary for them to follow me, since I will go to meet them this very day.”

The English king was as good as his word, for he immediately called his men to arms, broke camp, and marched toward Linlithgow, where they stopped for the night. Sometime during the middle of the night, the king’s destrier stepped on his master. The camp went into an uproar as the troops suspected treachery and imminent attack by the Scots, but when they learned the cause of the king’s injury, order was restored.

Since he was up already, Edward decided to advance, and the army passed through Linlithgow at dawn on July 22. “When they raised their eyes and they gazed upon the mountain opposite, they saw on the brow, many spearmen,” wrote Walter of Guisborough. “And believing that there was the army of the Scots, they hurried to ascend … but arriving in that place they found no one. They set up their tents there, and the king and the bishop heard a mass of Magdalene.” While the mass was in progress, English scouts spotted the Scottish army assembling for battle.

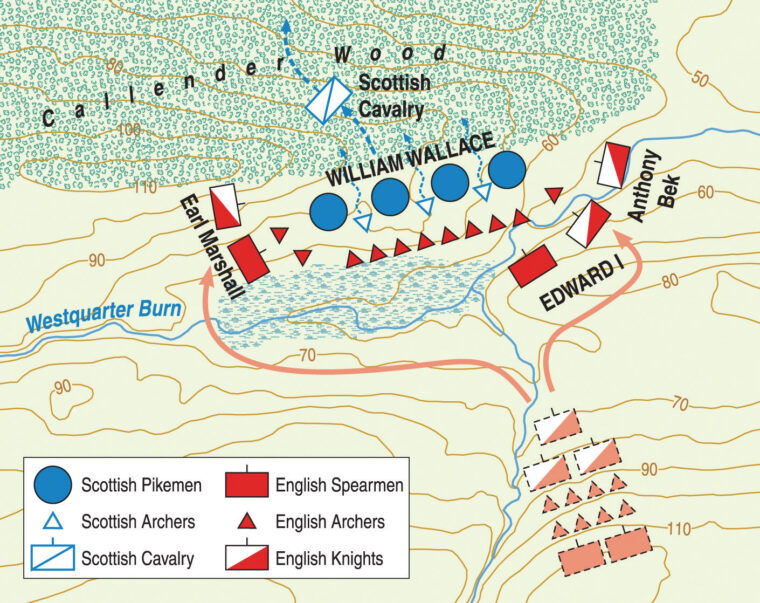

Modern historians disagree as to the exact location of the Battle of Falkirk. Some place the battlefield south of Falkirk and some north of the town. The chronicles are vague. “The Scots, indeed, stood all their foot in four companies, in the form of circular circles, on hard ground, and on one side next to Falkirk,” wrote Walter of Guisborough.

The Lanercost Chronicle is even less exact as to the location: “The Scots gave [King Edward] battle with all their forces at Falkirk.” However, the Salacronica of Sir Thomas Grey might provide the best information regarding the location. Grey was an English knight whose father, as mentioned earlier, barely survived Wallace’s attack on Lanark. When he writes, “They fought on this side of Falkirk,” he must mean the side from which the English were advancing. And that would place the battlefield south or southeast of Falkirk. Some modern accounts place the Scottish position to the south of Callendar Wood.

When mass was over and the Scots’ position was reported to the king, he decided that it was time for the army to have lunch since they had not eaten since the day before. But the English nobles were, as usual, impatient to join battle, and by way of persuading the king to skip lunch they pointed out that the only natural obstacle that separated the two armies was a small stream.

Edward, apparently unconcerned with respect to the Scots’ offensive capability, was unperturbed. But badgered by the glory-hungry aristocrats, he gave the order to advance. Walter of Guisborough provides the most detailed account of the fighting. In the aforementioned circular formations the Scottish “spearmen waited with their lances raised obliquely and with faces turned toward the circumference of the circles,” wrote the chronicler. “Between those circles there were certain intermediate spaces in which were stationed the bowmen … behind, were their horsemen.” The Scots had probably mustered 5,500 infantry and 180 cavalry.

The English army was divided into four “battles” (divisions) instead of the usual three. The four English battles were no doubt a response to the four Scottish formations (schiltrons). Immediately upon Edward’s order to advance, the first battle, 450 mounted men led by the Earl of Lincoln, “drew up … in lines toward the enemy, not noticing a bituminous lake in between [them and the enemy],” wrote Walter of Guisborough. “When they saw it, they went around it to the west, and so they were delayed a little.”

No trace of any bog remains today, but there must have been some kind of marshy ground some distance in front of the Scottish position, perhaps having something to do with the small stream, which caused the earl’s movement to his left.

The Bishop of Durham, leading 425 horsemen of the second battle, observed Lincoln’s detour to the west and the reason for it. He led his men to the east, where they rushed forward in order to have the honor of striking the first blow. Realizing that his contingent was outnumbered by the Scottish foot, and perhaps noticing the Scottish cavalry drawn up at a distance behind their infantry, possibly in place to attack the flank or rear of the bishop’s 425 men, “the bishop himself ordered them to wait until the king approached with the third battle,” wrote Walter of Guisborough. “Radulphus Basset de Drayton answered him and said, ‘It is not your place bishop to teach us now concerning military matters, you who ought to be concerned with saying mass. Go if you wish to celebrate mass, since we all will do, here on this day, those things which pertain to military matters.’”

Disregarding the bishop’s order, they immediately charged the schiltron on the Scots’ left. The long Scottish spears clashed with the English lances. At the same time, as Lincoln and his battle appeared on the Scot’s right, the Scottish cavalry fled without having engaged the enemy. Those few who did not flee took refuge in the schiltrons.

Although Walter of Guisborough does not mention the arrival of King Edward, who led 800 horsemen and 100 mounted crossbowmen, or the fourth battle of 425 cavalrymen led by Surrey, these divisions must have come up in support of the English horse that had already engaged and who were now turning their attention to the Scottish bowmen, drawn up in intervals between the schiltrons. The archers did not have much of a chance against the armored chivalry of England. Although they may have accounted for some of the 111 horses reported as killed that day, the archers died fighting over the body of their commander, Sir John Stewart.

“And so, with the archers killed, our men moved themselves toward the Scottish spearmen, who, as it was reported, stood in circles with their lances leveled in the manner of a dense wood,” wrote Walter of Guisborough. “While the horsemen were not able to enter because of the multitude of spears, they struck the outermost and stabbed many with their lances.”

At this point, there must have been a bit of a standoff. The schiltrons could not maneuver, but they outnumbered the English horse, which were unable to break them. It is now that Edward’s Welsh bowmen must have arrived: “Our foot shot them with arrows, and indeed, with round rocks … they stoned them,” wrote Walter of Guisborough. “And so, with many dead and others stunned, who, at the edges of the circles, had stood forth, and the rest of the front line recoiling back on those behind, the horsemen entered, killing all.”

Wallace fought his way out of the rout, leading what was probably by now the only disciplined force of Scots left on the field, perhaps a schiltron under his personal command. Wallace sent his men across the River Carron, to the northwest of Falkirk, while he held the ford with a small rear guard. At that place, while still mounted, Wallace engaged in single combat with Brian le Jay, Master of the Templars, and killed him with a single blow. Walter of Guisborough mentions the death of “the master of knights of the temple, who in following the fugitives into the bog was somehow intercepted and killed.” Walter’s bog is perhaps marshy ground near the River Carron. The Lanercost Chronicle, however, says that “the Master of the Templars” was killed “with five or six esquires, who charged the schiltrons of the Scots too hotly and rashly.”

The number of casualties given by the ancient chroniclers is hopelessly inflated. Nevertheless, Scottish casualties were undoubtedly heavy while English losses were substantially less. Edward went on to take Stirling Castle, but with supplies running low and his army dwindling as his feudal levies headed home, he returned to Carlisle on September 9.

Wallace resigned the Guardianship and was succeeded by Robert the Bruce and John Comyn. The former Guardian spent the next few years on the Continent, trying to drum up support for his cause. He returned to Scotland in 1303 and seems to have once again engaged in guerrilla war against the English.

Two years later, Sir John Menteith betrayed Wallace, and he was taken to London to be hanged, drawn, and quartered. In 1306, Robert the Bruce personally killed his Comyn rival and declared himself King of Scotland. Edward led an army north but died on July 7, 1307, leaving affairs in the hands of his son, Edward II, who would meet Bruce at Bannockburn on June 24, 1314, in yet another pitched battle between the two bitter foes.

The illistration of the Bishop of Durham is incorrectly showing the modern arms of the Bishop of Durham, (Robert Neville 1437-52 a cross patonce), but the Bishop of Durham in 1298 was Anthony Bek whose arms were a cross recirculee.,

Michael is correct about the heraldty of the Bishop of Durham. It had a red background with a white cross lined with stars.

A question regarding the numbers of the English force at Falkirk. Where did these figures come from? Also, what is MHN’s take on the numbers and composition of the Scottish force at Falkirk?