By David Alan Johnson

On board one of the transports headed for the island of Saipan in early June 1944, a battalion surgeon gave a group of Marines a lecture on what they could expect when they reached their destination. “In the surf,” he explained, were “barracuda, sea snakes, anemones, razor-sharp coral, polluted waters, poison fish, and giant clams that shut on a man like a bear trap.”

Warming to his subject, the doctor went on to tell everyone exactly what was waiting for them when they landed on the island itself: “Leprosy, typhus, filariasis, yaws, typhoid, dengue fever, dysentery, saber grass, hordes of flies, snakes, and giant lizards.” The men were also warned not to eat anything growing on the island, not to drink the water, and not to approach any of Saipan’s local inhabitants. After finishing his lecture, the surgeon paused, looked out at his audience, and asked if there were any questions.

After a moment, one private raised his hand. “Sir,” he asked, “why ‘n hell don’t we let the Japs keep the goddamn island?”

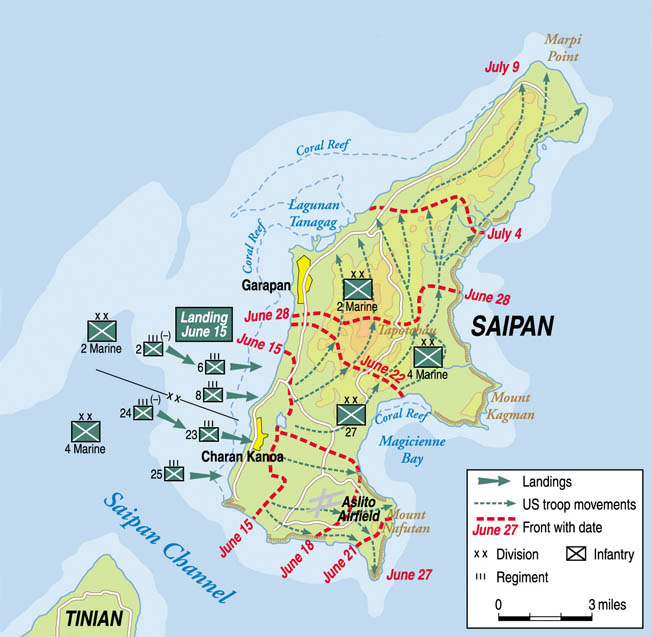

There was a very good answer to that particular question, although the surgeon did not tell the private what it was. The primary reason why Saipan was so highly prized and why the U.S. high command wanted to take the island from the Japanese was Aslito airfield, a Japanese air base on the southern part of the island. This was probably the most important enemy airfield between their massive naval base at Truk and the Japanese home islands.

Saipan also had a good harbor, Tanapag, which the Japanese had modernized and improved since the war began, as well as an unfinished airstrip on the north tip of the island. But the primary American objective was Aslito Field.

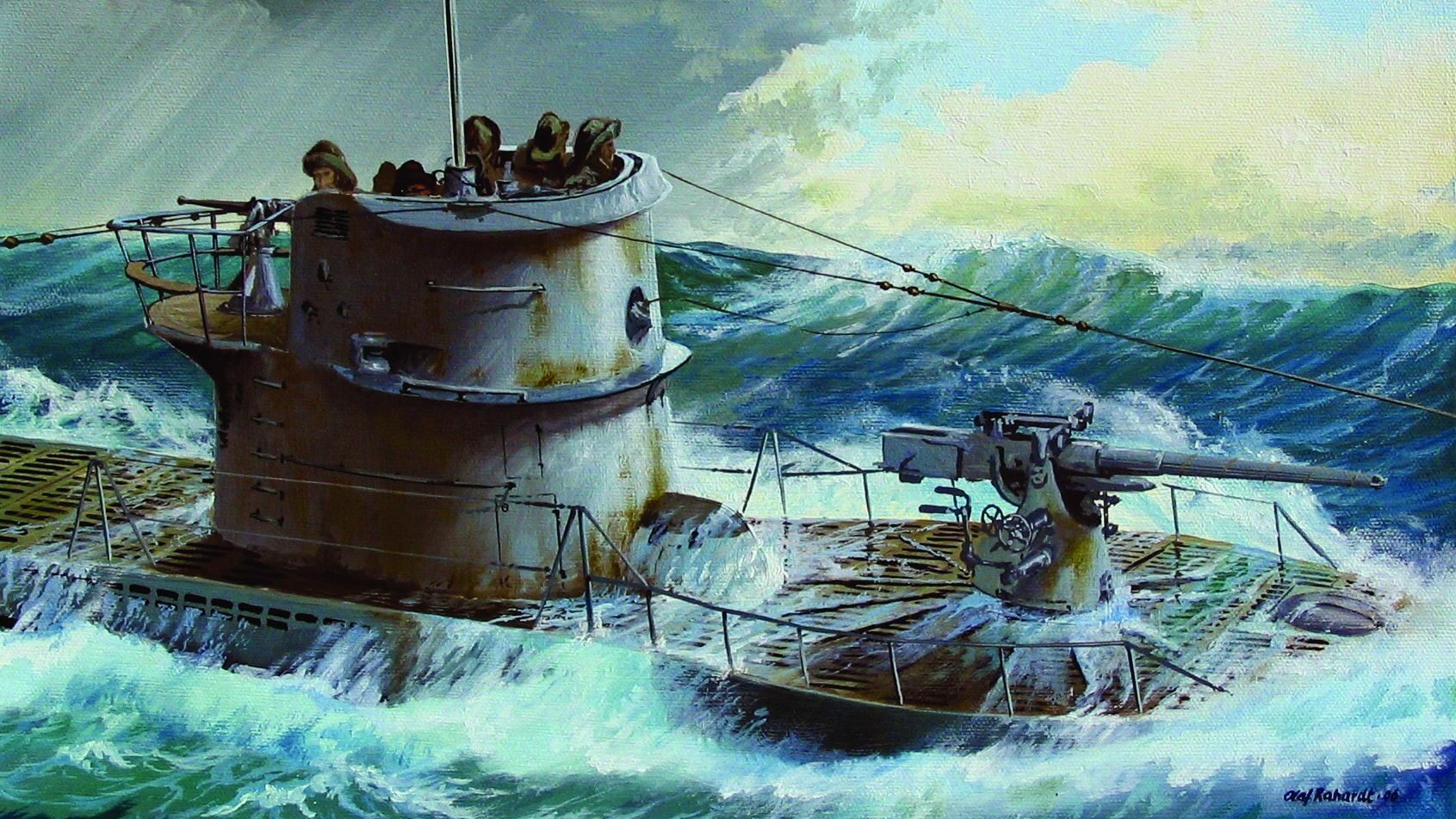

The Combined Chiefs of Staff had seen the strategic importance of Saipan a year and a half earlier, in January 1943. Saipan and the other islands in the Marianas chain would be invaluable as forward bases for refueling submarines and other warships as American forces island-hopped their way to Japan. But Aslito would be a part of the attack on Japan itself—as a base for the long-range Boeing B-29 Superfortress bomber. Tokyo was 1,500 miles from Saipan, within striking range of the Superfortress.

Saipan was also closer to the Japanese base at Truk, which has been described as “Japan’s Pearl Harbor.” Taking possession of Guam, Saipan, and Tinian—the largest of the Marianas Islands—would not only neutralize Truk but would also put B-29s closer to Japan than they had ever been.

The Japanese high command was also well aware of the strategic importance of Saipan and the Marianas and knew that the Americans would be turning their attention to the island chain at some point in the near future. On June 14, 1944, Admiral Chuichi Nagumo, commander of the newly created Central Pacific Area Fleet, wrote, “The Marianas are the first line of defense of our homeland. It is a certainty that the Americans will land in the Marianas Group either this month or the next.” He was absolutely correct. American forces would make three separate landings on Guam, Saipan, and Tinian. Saipan would be the first.

By the time Admiral Nagumo made this statement, about 30,000 Imperial troops had been sent to defend Saipan. Most of the troops were from the 43rd Division. Nagumo was sent to oversee the defense of the island. When he arrived, the news he received from the defending troops was anything but encouraging.

General Hideyoshi Obata, who commanded all ground forces in the Marianas, gave the admiral a sobering account of the situation. “Specifically, unless the units are supplied with cement, steel reinforcements for cement, barbed wire, lumber etc., which cannot be obtained in these islands,” he told the admiral, “no matter how many soldiers there are, they can do nothing in regard to fortifications but sit around with their arms folded, and the situation is unbearable.”

Actually, thousands of tons of building materials had been sent from Japan to build up the island’s defenses, but they never arrived; the ships carrying all the cement and barbed wire and lumber had been sunk by American submarines. There would be no more building supplies coming. The defenders would have to make do with what they had.

They would also need all the luck they could get. By early June, a flotilla of American ships—which is usually described as “massive”—had set sail from its bases and was steaming toward Saipan. This task force consisted of battleships, cruisers, and destroyers, along with transports carrying the men of the 2nd and 4th Marine Divisions. They would be followed by the U.S. Army’s 27th Infantry Division. Of the eight battleships in the invasion task force, four were veterans of the Pearl Harbor attack: Maryland, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, and California.

Aboard the transports, the men anxiously concentrated on preparing for the invasion. They belted .50- and .30-caliber machine-gun ammunition, sharpened their bayonets, and wondered what would be in store for them on an island most of them had never heard of.

On June 7, the Marines were given some news that helped take their minds off their own concerns, at least for a while. Half a world away, Allied forces had come ashore on the beaches of Normandy. Operation Overlord began the liberation of Western Europe from the Nazis. Reaction to the announcement varied from ship to ship.

Aboard most transports, the bulletin was short and to the point: “The invasion of France has started. That is all.” On the aircraft carrier Enterprise, mimeographed news releases were distributed to the men. Groups of three and four leaned over each other’s shoulders to read the releases as they came in, and the men shouted each other into silence whenever another announcement came over the loudspeaker. Most of the men throughout the task force reacted with relief and satisfaction when they heard the news, although some responded by saying “Thank God” to no one in particular.

The news of the Normandy landings was as welcome to Vice Admiral Richmond Kelly Turner, the commander of the Joint Expeditionary Force, as it was to everyone else in the task force. But Turner had more immediate things to worry about. This would be his fifth major amphibious operation after Guadalcanal, the Central Solomons, the Gilberts, and the Marshall Islands, and he probably knew more about this specialized type of warfare than anyone else. He would be putting all his knowledge and experience to use in the impending Marianas campaign.

Admiral Turner set the date for the invasion of Saipan for June 15, 1944. The landings on Guam and Tinian would depend upon how events turned out on Saipan—the sooner that Saipan could be secured the sooner the dates for invading Guam and Tinian could be decided. The overall operation for capturing the Marianas, the invasion, and securing of all three islands, was given the code name Forager.

While Turner’s expeditionary force made its way toward Saipan, a fast carrier group commanded by Admiral Marc A. Mitcher began a series of air strikes against Saipan and Tinian. On the morning of June 11, a total of 11 aircraft carriers launched more than 200 fighters and bombers against both islands. On Saipan they destroyed more than 100 Japanese aircraft.

Two days later, the battleships arrived at both Tinian and Saipan and began their own bombardment. At Saipan, they kept on shelling until just before the landing force went ashore. To the gunners on board the ships, it seemed that nothing could possibly be alive on the island, not after the pounding it had taken for the past two days.

Battleships, cruisers, and destroyers of the task force began their final bombardment of Saipan at 5:50 am on June 15. Twelve minutes later, Admiral Turner gave the order: “Land the landing force.” On every transport, the chaplain’s last prayers and blessings were broadcast over the ships’ loudspeakers. One chaplain said, “Most of you will return, but some of you will meet the God who made you.” An officer turned to a war correspondent and said, “Perish-the-Thought Department.”

It took until 8 am before the landing force was actually ready to land. Shortly before that hour, more than 700 landing craft filled with eight battalions from the 2nd and 4th Marine Divisions started for Saipan’s western coast.

The first of the landing parties came ashore on Beach Red 2 at 8:44 and came under heavy fire almost immediately. A Marine colonel, the operations officer of the landing force, described the scene in his report: “The opposition consisted mostly of artillery and mortar fire from weapons placed in well-deployed positions, as well as fire from small arms, automatic weapons, and anti-boat guns sited to cover the beach areas….”

American warships sailed back and forth off Saipan’s western beaches, firing at inland targets. Others entered the strait between Saipan and Tinian and unleashed their ordnance at Saipan’s southern tip. As the landing craft approached the shore, the defenders began shooting back. The battleship Tennessee and the cruiser Indianapolis, the flagship of Admiral Raymond Spruance, were both hit by Japanese shore batteries. As the landing craft made their runs toward the beach, they came under fire as well.

The run-in was about 1,500 yards, although it must have seemed a lot longer than that to the men in the landing craft. Shells exploded all around them; some of the boats were hit, and several were sunk. The rest kept going. There was no other option.

At the shoreline, the landing craft discharged their Marines, who ran as low and as fast as they could to get off the beach. While the Marines were landing, dozens of aircraft came in to strafe the Japanese defenses, and the warships kept pounding the shore batteries. An observer described the sight as organized bedlam.

North of the invasion beaches, Admiral Nagumo watched the landings from a 30-foot observation tower. The admiral stared out to sea at the fantastic array of American ships, absolutely transfixed by the sight. According to his yeoman, Mitsuhara Noda, who was standing nearby, Admiral Nagumo, who had been the commander of the Pearl Harbor attack force, was especially intrigued by the battleships that were standing offshore. He pointed out to Noda that “at least four” of those battleships had been sunk by his carrier-based aircraft at Pearl Harbor. Noda recalled that the admiral’s tone “indicated as much admiration as concern.”

The first objective of the Marines after they had fought their way off the beach was the abandoned village of Charan Kanoa. Most of the Americans expected to find flimsy little houses made of paper and bamboo. Instead, they found themselves facing a complex of one- and two-story concrete pillboxes, most of which were covered with bougainvillea in bloom. At the center of the village, the Marines came across another surprise—a baseball stadium, complete with a four-base diamond and a grandstand. A Buddhist temple stood next to the ballpark.

Captain John C. Chapin and his men of G Company, 24th Marines, 4th Marine Division stopped at Charan Kanoa to get some drinking water and to have a quick bath. As soon as they stopped, enemy mortar shells began exploding among the Marines, who were caught unprepared and in the open. Everyone had been so preoccupied with the pillboxes and with washing and relaxing that they did not notice a ruined sugar refinery in the distance or its tall smokestack. The smokestack was being used as an observation post. A Japanese spotter had made his way to the top of it and was calling mortar fire down on the Marines.

Before somebody finally discovered the spotter, Captain Chapin recalled, “We lost far more Marines than we should have.” He did not specify exactly how many of his men were killed and wounded, only saying that the observer “really caused a great number of casualties in G Company.”

The commander of the Japanese 43rd Division, General Yoshitsugu Saito, was optimistic about mounting a successful defense of Saipan. He was receiving encouraging reports that his troops were fighting back in spite of the U.S. warships and their murderous naval gunfire and also that the invading Americans were suffering heavy casualties. Both General Saito and Admiral Nagumo were astonished by the American show of force at Saipan, but they were far from intimidated by it. They were confident that reinforcements would arrive and that the invaders would be wiped out. No enemy would ever take Saipan!

The Marines kept coming ashore along with most of their artillery. To back up the Marines, units of the U.S. Army 27th Infantry Division landed on June 16. But General Saito kept the landing beaches under fire all day long, inflicting more casualties among the Americans who had already landed.

General Saito ordered a counterattack that night, hoping to push the Americans back into the sea before they could organize effective defenses. Only about 500 troops took part in the night attack, but General Saito sent 44 tanks to break through the American lines.

The tank assault was led by Colonel Hideki Goto’s 9th Tank Regiment. Just after 3 am on June 17, Colonel Goto opened the hatch of his Type 97 medium tank, stood erect in the open turret, and waved his cavalry saber over his head. The other tank commanders did likewise. Colonel Goto then slapped the side of his tank with his saber, which made a resounding clank. Once again, his junior officers followed his lead; they slapped their tanks with their sabers. With that ceremony out of the way, all the tank commanders closed their hatches and pointed their tanks toward the American lines.

The Marines could not see Goto’s tanks coming, but they could hear the clanking and rattling. They called the Type 97s “kitchen sinks,” among other things. Captain Clarke Rollen warned, “It sounds like a night attack coming,” and requested illumination from the ships offshore. The U.S. Navy warships responded by sending so many star shells that the jungle darkness suddenly turned into midday.

As soon as they caught sight of the Japanese tanks, the Marines opened fire with bazookas, 37mm guns, and hand grenades. The leading tanks caught fire, which lit up the others; a few of the tanks came to a stop. A Japanese officer climbed out of his machine, waved his saber, shouted a few orders, got back into his Type 97, and closed the hatch. Whatever the officer said was certainly effective. The tanks started moving forward again and were immediately hit by bazooka and 37mm fire.

One Marine, Pfc. Herbert Hodges, knocked out seven Type 97 tanks within a few minutes. Another Marine knocked out four tanks with his bazooka before running out of ammunition and disabled a fifth tank with a hand grenade.

By dawn, all but one of Goto’s tanks had been destroyed. One was literally blown apart by an offshore destroyer’s five-inch gun at about 7 am. The burning wrecks of Goto’s tanks littered the battlefield; General Saito’s night tank attack turned out to be a complete failure.

By the morning of June 17, the Saipan beachhead had been secured. It had cost about 3,500 casualties, but the landing beaches belonged to the American troops. The rest of the island was far from being secured, however, and Aslito airfield was still in Japanese hands.

Less than an hour after their night encounter with Goto’s medium tanks, units of the 2nd Marine Division began an advance of their own. By the end of the day on June 17, the beachhead north of Beach Green 3 had more than doubled in size, and Marine General Holland M. “Howlin’ Mad” Smith, the commander of all American ground troops on Saipan, had set up his command post at Charan Kanoa.

Units of the 165th Regiment of the U.S. Army’s 27th Infantry Division reached the perimeter of Aslito Field by 2 pm, and the 124th Marine Regiment, 4th Marine Division had captured what has been described as “a commanding height” overlooking the airfield.

General Saito and Admiral Nagumo were still expecting reinforcements to come to the relief of the Japanese troops on Saipan. A Japanese fleet under Admiral Jisaburo Ozawa had been ordered to “attack the enemy in the Marianas area and annihilate his fleet.” With the American warships out of the way, Japanese reinforcements would be able to land on Saipan and link up with General Saito’s troops. If the Americans could be isolated and cut off from any further supplies, it would only be a matter of time before the enemy invaders were all either killed or captured.

Admiral Ozawa’s Mobile Fleet made contact with Admiral Marc Mitcher’s Task Force 58 on June 19. The results of the ensuing battle were not what General Saito, Admiral Nagumo, or Admiral Ozawa expected. The Battle of the Philippine Sea was a disaster for the Japanese Navy. Ozawa’s Mobile Fleet lost three aircraft carriers, and hundreds of aircraft were shot down in what became known as “The Great Marianas Turkey Shoot.” Ozawa withdrew. With no naval forces in the area, the Japanese garrison on Saipan was isolated.

A few attempts were made to reinforce the Japanese troops on Saipan. The commanding officer on Tinian tried to send soldiers across the Saipan channel several times, but the narrow strait was too closely watched by American warships for any of them to make the crossing. Two infantry units were also sent from Guam in 13 landing barges filled with men and artillery. They never came any closer to Saipan than the island of Rota, which is about one-third of the way between Guam and Tinian. The troops remained on Rota until the end of the war.

In his history of U.S. naval operations in World War II, Samuel Eliot Morison wrote, “As a result of the naval victory all Japanese forces ashore were sealed off and doomed.” He went on to say that the defenders of Saipan “forced the United States to pay a heavy price for the island.”

A Japanese tanker who had not taken part in the disastrous night attack of June 16-17 wrote in his diary: “The remaining tanks in our regiment make a total of 12. Even if there are no tanks, we will fight hand to hand. I have resolved that, if I see the enemy, I will take out my sword and slash, slash, slash at him as long as I last, thus ending my life of 24 years.”

General Saito organized his remaining infantry and artillery units into defensive positions around Mount Tapotchau, rugged terrain that favored the defenders. Some of the nicknames given to these positions were “Hell’s Pocket,” “Death Valley,” and “Purple Heart Ridge.” Japanese soldiers used the caves in the vicinity of Mount Tapotchau to ambush the Marines, sometimes making attacks by night.

American troops were as determined to capture Saipan as the Japanese were to defend it. Marine Captain John C. Chapin watched a unit of the 4th Marine Division make an attack on June 20. The attack took place about a quarter of a mile in front of him, which gave Chapin a perfect view of the action.

The Marines “were assaulting Hill 500,” he said, “the dominant terrain feature of the whole area, and it was apparent that they were running into a solid wall of Jap fire.” “But using [artillery] timed fire, smoke, and tanks, they finally stormed up the hill and took it.” By this time, the operation’s primary objective, Aslito Field, had already been captured. The airfield was renamed Isely Field, after Commander Robert H. Isley, who had been killed five days earlier. Commander Isely’s TBF Avenger had been hit by antiaircraft fire and crashed on the south side of the airfield’s runway.

Four days after its capture, P-47 Thunderbolts of the 19th Fighter Squadron landed at Isely Field from the escort carriers Manila Bay and Natoma Bay. The fighters were immediately fitted with launching racks for rockets and proceeded to deliver a rocket strike on Tinian a few hours later. By the autumn of 1944, B-29 Superfortresses would be flying bombing raids against cities on the Japanese mainland from Isely Field.

The Saipan operation also saw an unfortunate occurrence of interservice rivalry. On June 22, the U.S. Army’s 27th Infantry Division had been inserted into the center of the line between the two Marine divisions as they moved forward. The Marines took Mount Tipo Pale and then Mount Tapotchau. Unfortunately, Maj. Gen. Ralph C. Smith’s 27th was unable to maintain pace with the more aggressive 2nd and 4th Marine Divisions on its flanks, and the front line sagged in the middle.

Marine General Holland Smith, who held the Army in low regard anyway, was unhappy with the performance of the 27th Infantry Division. As far as he was concerned, the 27th was not aggressive enough, and he blamed the division’s commander, Maj. Gen. Ralph Smith, for its shortcomings. Holland Smith complained to Admiral Turner that Ralph Smith’s division was slowing the overall advance on Saipan and suggested that its commanding officer should be relieved of his command. Agreeing that a change of leadership would get the 27th Division moving again, Turner and his superior, Admiral Raymond Spruance, approved the request, replacing the division commander with Army Maj. Gen. Sanderford Jarman.

The change in command did not seem to make much difference in the speed of the advance up Saipan. While the 27th Division fought on, the 2nd Marine Division endured three days of brutal, relentless fighting marked by furious banzai charges. On the fourth day, the Japanese pulled back into Saipan’s treacherous interior, hoping the terrain might slow the American advance.

The terrain was perfect for the Japanese defenders. The Americans’ progress was impeded as much by the difficult landscape as by the enemy. In fact, the caves and ridges that were giving Japanese troops excellent snipers’ posts and sweeping fields of fire were holding up the American advance more effectively than General Saito’s diminishing number of troops. By June 25, only about 1,200 able-bodied Japanese soldiers and three tanks remained on Saipan.

One of Saito’s commanders, General Keiji Igeta, radioed Saito’s headquarters that Saipan could not be held. “The fight on Saipan as things stand now is progressing one-sidedly,” the Japanese officer reported, “since along with the tremendous power of his barrages, the enemy holds control of sea and air.” Any lingering optimism had disappeared. But there would be no surrender. Saito’s message back to Igeta ended, “The positions are to be defended to the bitter end, and unless he has other orders, every soldier must stand his ground.”

American units continued to push their way north in spite of Japanese resistance. A private first class with the 23rd Marine Regiment described how the men in his unit dealt with enemy cave defenses. “Quite often there would be multiple cave openings, each protecting another,” he recalled. “Laying down heavy cover fire, our specialist would advance to near the mouth of the cave. A satchel charge would then be heaved into the mouth of the cave, followed by a loud blast as the dynamite exploded.” Sometimes hand grenades were used instead of a satchel charge.

Warships offshore added their support to the advancing troops. A Japanese prisoner told his interrogators that naval gunfire was the most dreaded of all American weapons, even more than field artillery or aerial bombardment, adding that it was the “greatest single factor in the American success” on Saipan. Occasionally, some of the warships would be detached to take part in the softening up of Guam and Tinian in preparation for the landings on those islands.

Just after midnight on June 27, about 500 Japanese soldiers managed to penetrate the American lines around Isely Field, where they set fire to a P-47 and damaged two others. After doing as much damage as possible at Isely Field, the Japanese continued on to some nearby high ground, where they encountered a Marine position. The battle went on for most of the morning. The Marines lost 33 killed and wounded; Japanese losses were 140 men. Escaping Japanese were found and killed later in the day.

By the last days of June, the end was clearly in sight for the Japanese forces on Saipan. General Saito had moved his headquarters to a cave at the northern end of the island, and one of his battalions had been reduced to 100 men. But the Japanese troops resolutely refused to give up. According to one American account, “Enemy resistance was isolated, sporadic, and desperate.”

American troops kept moving north. On July 3, units of the 2nd Marine Division occupied the city of Garapan. It had once been the home of 15,000 inhabitants; now it was a deserted ruin. The belongings of thousands of civilians littered the streets—everything from pots and pans to bits of clothing, which they had left behind when the city was abandoned. An occasional Japanese sniper would fire at a Marine patrol from a rooftop, but only sporadic resistance was encountered.

During the night, about 200 Japanese made their way back to Garapan and arrived in time to give the Marines a rude early morning surprise. After a vicious fight, the Marines chased the Japanese right out of the city. They set up a command post on one of Garapan’s main roads, which they renamed Broadway, just across the street from what was left of the local bank.

The Japanese fell back to another defensive line just north of Garapan. At this stage, there were not many Japanese left. The men who managed to survive were all desperately hungry. Many were reduced to eating tree bark and grass.

Some Japanese soldiers stayed behind, usually holed up in caves, to slow the American advance as best they could. Sometimes they smeared blood on themselves and stayed perfectly still as the Americans walked past them, jumped up, and fired at the unsuspecting soldiers. The Americans responded to this by bayonetting all Japanese bodies—the dead and the wounded. “You had to do it!” one Marine officer explained.

Throughout the first week of July, the American troops advanced toward Marpi Point, Saipan’s northernmost tip. Japanese troops steadily retreated before the Americans. Soon they had nowhere left to retreat. General Holland Smith feared that the remaining enemy troops would attempt an all-out suicide charge at the American lines—a banzai attack. When Japanese troops were cornered, this was their usual response.

At Japanese headquarters, it was decided that an attack would be made by all remaining troops in the area. On the evening of June 5, the headquarters staff ate the last of their rations. One staff officer asked General Saito if he intended to take part in the attack. Admiral Nagumo answered instead. He said that he and General Saito, along with General Igeta, would commit suicide.

Most of the following day was spent organizing the coming attack. Soldiers and sailors in nondescript uniforms, armed with weapons ranging from rifles to swords to bamboo spears, gathered for the assault. An onlooking staff officer thought the men looked like “spiritless sheep being led to the slaughter.”

On July 6, General Holland Smith paid a personal visit to the senior officers of the 27th Division to warn them that a banzai attack was likely to come down the coast along the flat ground of the Tanapag Plain within 12 hours.

General Smith was absolutely correct. So far, the American advance from the southern part of the island had been almost unopposed. One Marine called it a “rabbit hunt.” The constant movement of the American troops had prevented the Japanese from forming anything resembling a cohesive defensive line. By July 6, all surviving Japanese troops had been boxed into the northern end of Saipan.

At about 4 am on July 7, the defenders reached their jumping-off point and prepared to charge down the northwestern shore of Saipan toward Tanapag village. As the sky began to brighten, the sound of a rifle was heard in the distance—the signal to attack! Between 3,000 and 4,000 men began moving forward. They ran headlong down the Tanapag Plain and threw themselves at the 1st and 2nd Battalions of the 105th Infantry Regiment, 27th Infantry Division.

“Suddenly there was what sounded like a thousand people screaming all at once, as a hoard of ‘mad men’ broke out of the darkness before us,” recalled a Marine who witnessed the attack. An officer in the 105th Infantry said, “It was like a stampede staged in the old Wild West movies…. These Japs just kept coming and coming and didn’t stop.” Another account compared the Japanese charge with “crowds swarming onto a field after a football game.” Every Japanese soldier had just one thought in mind—to kill as many Americans as possible before being killed himself.

The defending American soldiers and Marines fought back as best they could against such an onslaught. “Our weapons opened up, our mortars and machine guns fired continually,” one Marine reported. “Even though Jap bodies built up in front of us, they still charged us, running over their comrades’ fallen bodies. The mortar tubes became so hot from the rapid fire, as did the machine-gun barrels, that they could no longer be used.”

Behind the able-bodied troops came hundreds of walking wounded. These men belonged back in the field hospital; some of them were on crutches. They had been issued bamboo spears and swords and limped along behind the main attack, ready to die for the Emperor.

The American defenders could not help but fall back under the pressure of this human tidal wave. They managed to slow down the charge with artillery, including 105mm howitzers, .50-caliber machine guns, and sometimes bayonets and rifle butts. The two battalions of the 105th Infantry formed a defensive perimeter near Tanapag village.

By late afternoon, the Japanese spearhead finally lost steam and then was stopped altogether. The 105th Infantry’s two battalions had suffered nearly 1,000 casualties but had killed nearly 3,000 Japanese. A final count of all Japanese killed in the suicide charge came to just over 4,300.

Saito, Nagumo, and Igeta had already made good their pledge to commit suicide. All three of them had been shot through the head by their aides at about 10 am on July 6. Admiral Nagumo especially requested that he should be shot by a naval officer. Morison thought it ironic that the “proud commander of the First Air Fleet and Pearl Harbor Striking Force, of the crack carriers that had ranged victoriously from Oahu to Trincomalee,” should die such an obscure death in a cave on Saipan.

On the day following the Japanese suicide charge, the Americans began their final mopping up of the island. Holland Smith transferred most of the 27th Division to what amounted to strategic reserve and combined units of the 2nd and 4th Marine Divisions and the 105th Infantry Regiment in a final northern sweep toward Marpi Point. The remaining Japanese forces were not about to let the advance go unchallenged. They came at the Americans in suicidal rushes that could have only one outcome—miniature versions of the suicide charge that had been made the preceding day.

Marines finally reached Marpi Point on July 9, and units of the 4th Division captured a still unfinished airstrip on the northern tip of the island. At 4:15 pm, Admiral Turner announced that Saipan was officially secured. The Americans next turned their attention to Saipan’s sisters, Guam and Tinian.

The Battle of Saipan might have been officially over, but the fighting was far from finished. For several weeks small groups of Japanese soldiers still attacked the occupying American troops from hidden caves. Some of these attacks were made at night. Destroyers furnished star shell illumination, and sometimes gunfire, in support of the American units.

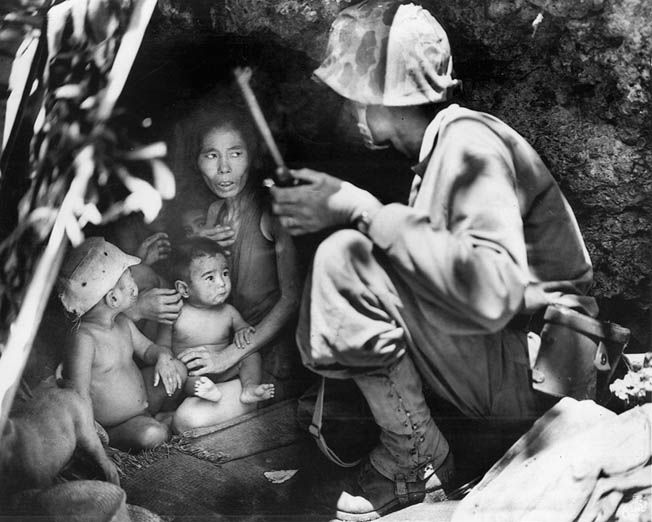

A flag-raising ceremony was held at Holland Smith’s headquarters at Charan Kanoa on the morning of July 10. But a grisly postscript to the capture of Saipan began the following day. Hundreds of Japanese civilians, probably as many as a thousand, committed suicide rather than allow themselves to fall into the hands of the enemy. Japanese government propaganda had told the civilian population on the island that the Americans were devils who would kill and mutilate anyone they captured. Most of the civilians who lived on Saipan, about 25,000, were uneducated, and many believed what they were told.

Some jumped from the northern cliffs into the sea. The cliffs were “very steep, very precipitous,” a Marine observer wrote. “The women would come down and throw the children into the ocean and commit suicide.” Others were killed by Japanese soldiers. “The Jap soldiers would not surrender, and would not permit the civilians to surrender,” the same Marine recalled. “I saw with my own eyes women, some carrying children, come out of the caves and start toward our lines. They’d be shot down by their own people.”

Soldiers also killed themselves. Some estimates put the number of military suicides as high as 5,000. “It was a sad and terrible thing,” an American reflected, “and yet I presume quite consistent with the Japanese rules of Bushido.”

Another American officer took a less sympathetic point of view: “This episode was a grim reminder that the road to Tokyo would be long and hard.”

Japanese dead, including suicides, totaled between 23,000 and 24,000, depending upon which source is consulted. American casualties numbered between 3,000 and 3,500 killed. Admiral Morison gives the number of killed and missing as 3,426, and wounded as 13,099, for a total of 16,525. Saipan was a very costly operation for U.S. forces, but it was a disaster for Japan.

“I have always considered Saipan a decisive battle for the Pacific offensive,” General Holland Smith wrote. “Saipan was … the naval and military heart and brain of the Japanese defense strategy.” The German naval attaché in Tokyo agreed with General Smith. “Saipan was really understood [in Tokyo] to be a matter of life and death,” he said. General Smith himself had predicted that “the fate of the Empire will be decided in this one action.”

Japanese officials in Tokyo certainly did understand the implications of what had happened at Saipan. One of the most immediate repercussions relating to the loss of the island was the fall of Prime Minister Hideki Tojo and his government. Tojo resigned on July 18, along with his entire cabinet.

In the wake of Tojo’s resignation and the loss of Saipan, there was some talk that his successor, General Kuniaki Koiso, might even begin peace negotiations. But no high-ranking Japanese officer or politician would propose peace with the Allied powers. The war in the Pacific went on for another year.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments