By James G. Bilder

Described in one U.S. Army report as “the quiet paradise for weary troops,” the tiny nation of Luxembourg was viewed by American commanders in late 1944 much like Belgium—liberated, safe, and an ideal location for combat-worn troops to rest and for untested replacements to get exposed to outdoor living and military routine before being exposed to combat.

The largest portion of the Battle of the Bulge story has, of course, usually been devoted to how the main German thrust of Hitler’s last and most desperate gamble was halted by the 101st Airborne “Screaming Eagles” Division at the Belgian crossroads city of Bastogne. Even after 70 years it still remains a fundamental study for amateur and professional historians alike.

Lesser known is that the German offensive in the Ardennes was not limited to Belgium and the northern drives toward the port of Antwerp and the capital city of Brussels, but actually had a sizable southern flank in Luxembourg, where the crossroads were of no less value and the fighting was every bit as ferocious.

[text_ad]

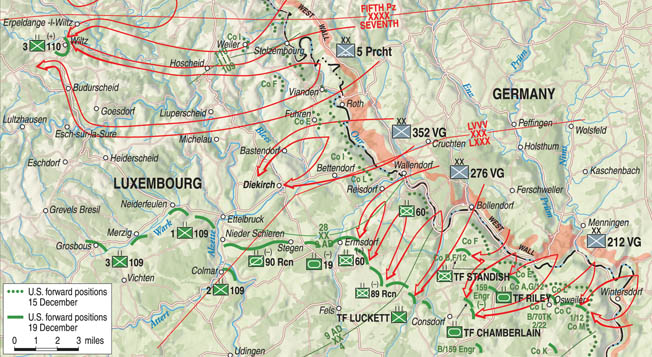

While SS General Sepp Dietrich’s Sixth Panzer Army was racing toward Antwerp and General Hasso von Manteuffel’s Fifth Panzer Army was driving toward Brussels (with General Gustav-Adolf von Zangen’s Fifteenth Army in reserve far to the north), it was General Erich Brandenberger’s Seventh Panzer Army that cut into the northern half of Luxembourg. Brandenberger was responsible for the southern flank of the Bulge and protecting the underbelly of Manteuffel’s force.

Brandenberger’s force consisted primarily of infantry, with limited armored support, and Third U.S. Army commander Lt. Gen. George S. Patton, Jr., would respond in kind when assembling the necessary units to counter his enemy’s moves. The battle in Luxembourg would be primarily an infantryman’s war with the footsloggers on both sides going toe-to-toe in some of the most brutal fighting, under some of the most horrific conditions, in all of northwestern Europe.

Erich Brandenberger vs George S. Patton

The commanders squaring off against one another were both highly accomplished and capable but could not have been more dissimilar in style, method, and appearance. At 52, Brandenberger was short, pudgy, bald, and normally wore spectacles (occasionally, pince-nez). Patton, seven years his senior, had a commanding presence (despite a high, squeaky voice) with a solid frame and enough white hair to make for a distinguished portrait.

Both men had served in combat during World War I. Patton, trained as a cavalryman and always a believer in mobility, led his FT-17 Renault tanks on foot at St. Mihiel and the Argonne. He was wounded in the leg at Cheppy during the Argonne battle, and his leadership and courage were recognized when he was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross and a Purple Heart Medal that came 14 years later in 1932.

in the snow and sub-freezing temperatures near Doncols, Luxembourg, for a possible enemy attack, January 1944.

Brandenberger had been an artillery officer in the Great War and was awarded the Iron Cross, both First and Second Class, for his combat actions. The static battle lines of World War I and limited mobility of artillery pieces in that conflict made him accustomed to slower paced movements. He was, however, given command of the 8th Panzer Division in 1941 and awarded the Knight’s Cross, the Third Reich’s highest military decoration, for his actions on the Russian Front.

These circumstances could not change the fact that Brandenberger was primarily a staff officer, both by nature and experience, and remained a conservative and methodical commander. This was in stark contrast to Patton, who was not only bold but also daring—sometimes to the point of recklessness.

A Panzer Army in Name Only

Brandenberger was given command of the Seventh Panzer Army in early September 1944. He was not highly regarded by his new commander, Field Marshal Walther Model. Model had been in the German Army since 1910. He fought in the First World War and earned the Iron Cross, First Class, at Arras, and served on both the Eastern and Western Fronts during World War II. He had been an Army commander since January 1942 and had turned so many potential catastrophes into German victories, or at least German survivals, that he was referred to as “Hitler’s Fireman.”

In the autumn of 1944, Model was in charge of Germany’s Army Group B (after Erwin Rommel’s successor, Günther von Kluge, committed suicide on August 17) and would be responsible for directing Hitler’s Ardennes counteroffensive codenamed Wacht am Rhein (Watch on the Rhine). Model seldom consulted Brandenberger during the planning phase of the offensive, but the two men were in agreement about the mission’s overall objective—an offensive that was doomed to failure.

When the battle loomed on December 15, 1944, Brandenberger’s Seventh Panzer Army was “panzer” in name only, as it consisted of the 212th, 276th, and the 352nd Volksgrenadier Divisions (the latter made up mostly of replacements from the Luftwaffe and Kriegsmarine without real combat experience), and was supplemented with the 5th Fallschirmjäger (Parachute) Division. These were all infantry divisions.

Even with some 60,000 men, these forces were understrength, undertrained, underequipped, and a number were limited in combat experience. The Seventh was clearly the stepchild of the German armies in the Ardennes, and Brandenberger was fortunate in that the American units serving in Luxembourg at the opening of the battle were greatly limited in number.

Since the dense Ardennes Forest was considered by the Allies virtually impenetrable despite the fact that the Germans had launched their May 1940 assault on the West through these same woods, it was regarded as the perfect safe haven for American units to recuperate and resupply. All other circumstances indicated continued quiet as the winter was starting out unusually cold and snowy, and the Germans had not mounted a major winter offensive in almost 190 years.

Ivy, Keystone, and Phantom

The only immediate obstacles in Brandenberger’s path were a regiment from the 4th Infantry “Ivy” Division in the south, a regiment from the 28th Infantry “Keystone” Division in the north, and a largely combat naive infantry battalion from the 9th Armored “Phantom” Division in the center.

The 4th Division was Regular Army and had landed at Utah Beach on D-Day. It had been engaged in heavy fighting ever since and had just come from the killing grounds in the Hürtgen Forest, where the division had suffered a casualty rate in excess of 40 percent.

The 28th, on the other hand, was a federalized National Guard Division from Pennsylvania. The division had arrived in Normandy in late July and fought in the hedgerows as well as the campaign in northern France. The 28th, too, had been badly mauled during the slugfest in the Hürtgen Forest, with roughly a third of the division becoming casualties. In fact, Maj. Gen. Norman “Dutch” Cota’s 28th Division had been so badly torn up by the enemy that the Germans gave them their own nickname in reference to the unit’s red keystone insignia: the “Bloody Bucket” Division.

Major General John W. Leonard’s 9th U.S. Armored Division had come to France in late September and did not arrive on the front lines until late October. Its actions thus far had been primarily confined to patrolling the quiet sector of the front along the border between Luxembourg and Germany.

Both Belgium and Luxembourg in this area are composed of hills and significant elevations that are covered with thick concentrations of trees and, in the winter, blanketed by heavy snowfalls. This made control of the roads essential, as it was impossible to traverse the off-road areas with vehicles or any meaningful numbers of troops. The important crossroad towns within the 109th Regiment’s area of responsibility—Diekirch, Ettelbruck, Grosbous, Heinerscheid, and Mertzig—were the most valuable real estate imaginable and prime objectives for the coming German counteroffensive.

The 109th Regiment of the 28th was in the northern end of Brandenberger’s path. When the battle started, the 109th was headquartered in Ettelbruck, southwest of Diekirch, under the command of Lt. Col. James Rudder, who had commanded the U.S. Rangers during the assault on Normandy’s Pointe-du-Hoc, and he was determined to do everything possible to hold his ground.

Crossing the Rivers

The timetable called for Brandenberger’s forces to jump off from the German side of the Our and Sauer Rivers at 6 am on December 16; they were to be 10 miles west of the river near Wiltz by day’s end, but there was one major problem: getting across the rivers. The 5th Parachute Engineer Battalion was tasked to erect a bridge across the Our, and ferrying equipment was to be put into place to get attacking units across, but such activities would take time.

The 14th Parachute Regiment had orders to cross the Our in the north near Stolzembourg, drive past Putscheid and Weiler, and seize a crossing point on the Wiltz River west of Hoscheid. Simultaneously, the 15th Parachute Regiment was to cross the Our at Roth and Vianden a few miles south of Stolzembourg, then establish a bridgehead over the Alzette River at Bourscheid. The 13th Parachute Regiment was to wipe out any American units in the area that might resist.

The preparatory artillery barrage began 30 minutes before the German troops started to cross the icy, swollen rivers, but the bridge or ferrying equipment for the Our was late in arriving. Once American observers saw the German engineers trying to construct their bridging equipment, they saturated the far bank with mortar and artillery fire.

It was not until the early evening of December 17 that the German assault gun brigade, antitank battalion, and vehicles of the 15th Parachute Regiment started across. The delay gave the Americans an opportunity to harass and impede the oncoming Germans at almost every area they attempted to cross.

After the Germans struggled across the Our, American units holding the high ground east of Ettelbruck stopped the left flank of the advancing 352nd Volksgrenadier Division as well as the neighboring 276th Volksgrenadier Division’s right flank.

Near Ettelbruck, Rudder’s regiment was grossly outgunned and still in a weakened state (not to mention 20 percent understrength), but its reputation as hell fighters was well earned. In fact, some of the members of the regiment’s 3rd Battalion were scheduled to be formally decorated that day for valor as a result of their recent actions in the Hürtgen.

When the attack began, Rudder was advised by the nearby 9th Armored to fall back, but he disregarded the recommendation and decided to secure whatever strongpoints he could to form anything resembling an effective defensive line.

Rudder had been keenly aware of the strategic importance of the Ettelbruck-Diekirch line and, because of his limited resources, had skillfully booby trapped a number of its approaches. Rudder’s task was daunting and pragmatically hopeless, but he was fortunate to have the regiment’s 3rd Battalion in Diekirch. He ordered the 3rd’s commander, Major James McCoy, to immediately cannibalize all his units to convert every soldier into an infantryman. McCoy was then to deploy his meager forces in the most effective way possible, which he did by forming a defensive line ahead of Diekirch.

McCoy had heavy weapons in the form of .30- and .50-caliber machine guns along with a couple of 81mm mortars and support from a nearby antitank unit equipped with 57mm (M1) antitank guns.

For two days the Americans succeeded in fending off the Germans with a roadblock at Bastendorf, a mile north of Diekirch, before the enemy renewed its attack with armor. On the afternoon of the 18th, German infantry and two panzers approached the 109th’s positions. In the ensuing fight, all six of the antitank company’s 57mm guns were knocked out and a supporting Sherman tank was destroyed. The Germans broke through the American lines with a Tiger and two Jagdpanzers along with a significant number of supporting infantry.

Rudder’s position was untenable and, as much as it pained him, he requested and was given permission to fall back toward Diekirch. The GIs—infantry, armor, artillery, and a field hospital—withdrew under cover of smoke while blowing bridges over the Sauer River. The 109th was reduced to a shadow of its former self; some 500 officers and men had been killed, wounded, or were missing. But their stiff resistance delayed the German advance in that sector.

The situation worsened for the 109th Regiment the following day when Diekirch had to be evacuated. Most of the civilians evacuated as well. The 109th had fought tenaciously and would later be awarded a Presidential Unit Citation for its actions during the opening days of the battle. Its exceptional courage typified the determination of American units throughout the Ardennes.

Despite the casualties inflicted by the 109th, the German 5th Fallschirmjäger Division under Colonel Ludwig Heilmann had traversed the Our River to the north of Diekirch with 15,000 men in a classic pincer movement. The southern portion of the pincer had gotten past Vianden and as far as Walsdorf on the first day. Just south of Heilmann was the 352nd Volksgrenadier Division under Colonel Erich Schmidt. Schmidt, too, moved in a pincer as he took on McCoy’s 3rd Battalion. The southern portion of the German assault had moved on the important crossroads of Diekirch while the northern portion had continued west before turning southward on Ettelbruck.

Beneath all this, the 276th Volksgrenadier Division, in the center of the German advance, crossed the Our/Sauer River junction near Wallendorf and moved ahead under the cover of fog but soon ran into the 60th Armored Infantry Battalion (AIB) from the U.S. 9th Armored Division. The battalion was under the command of Lt. Col. Kenneth Collins.

Collins, like his unit, was well trained but untested in battle. The 60th AIB had less than a thousand men, but it did have armored half-tracks with .30- and .50-caliber machine guns mounted on them. The men instinctively took high points and were fortunate enough to have artillery support from their 3rd Armored Field Artillery Battalion.

The Germans responded with rocket fire from their nebelwerfers (multibarreled rocket launchers) and proceeded to surround the isolated infantry companies. Collins managed to scrape together some medium and light tanks (Shermans, Stuarts, and Chaffees) with combat engineers acting as supporting infantry, and a counterattack was planned for December 18 to rescue the pockets of surrounded GIs. Collins’s actions kept the Germans off balance and derailed their plans for rapid advance in that sector.

Franz Sensfuss: Brandenburger’s Ace in the Hole

The major problem for the German 276th, and good fortune for the Americans, was that it had the largest number of inexperienced and poorly conditioned enlisted personnel in Brandenberger’s Seventh Army. Even worse, many of their NCOs were “gun shy,” as they had just been returned to the ranks after recovering from previous battle wounds.

The 276th’s commander, Lt. Gen. Kurt Moehring, was competent, respected, and well liked by his troops. But just two days into the offensive Moehring made a fatal error in judgment when he decided to use a captured American jeep for transport to his command post. He was shot and killed, almost certainly by friendly fire, on the main road between Grundhoff and Beaufort. Maj. Gen. Hugo Dempwolff succeeded Moehring.

Brandenberger felt his ace in the hole was the 212th Volksgrenadier Division, under the command of Lt. Gen. Franz Sensfuss. The men of the 212th were the mirror opposite of those in the 276th. They had fought in the siege of Leningrad and had extensive experience fighting in harsh winter conditions.

The official U.S. Army history noted, “After three years of campaigning on the Eastern Front the [212th Volksgrenadier] division had been so badly shattered during withdrawals in the Lithuanian sector that it was taken from the line and sent to Poland, in September 1944, for overhauling. The replacements received, mostly from upper Bavaria, were judged better than the average although there were many 17-year-olds.”

In Sensfuss, the men of the 212th had a leader worthy of command. A career officer, Sensfuss had been highly decorated in both world wars and was a very cunning commander. He thrived on information and calculated his risks on reliable intelligence.

Sensfuss knew from German spies in Luxembourg City that the town of Echternach, on the bank of the Sauer, was being held by elements of the 12th Regiment (Colonel Robert Chance commanding) of the 4th U.S. Infantry Division. The 4th had been under the commanded of Maj. Gen. Raymond O. “Tubby” Barton since the summer of 1942.

Barton, a West Point graduate and combat veteran of World War I, was a scrapper and a very capable commander. Before the counteroffensive began, Barton was wary of the seemingly peaceful atmosphere and had Colonel Chance deploy their meager resources carefully with lightly manned outposts near the Sauer River and rifle companies in the nearby cities and towns.

As recently as December 7, the 12th Regiment had been described in an official army report as “a badly decimated and weary unit.” The division in total had lost over 5,000 men in combat and another 2,500 non-battle casualties to trench foot and exposure. The men of the 4th Division were seasoned veterans and, while they had been bloodied from their recent campaign in the Hürtgen Forest, they were far from beaten or demoralized.

The Germans, much to their chagrin, soon discovered this as they attempted to cross the Sauer in rubber boats. Like the GIs in the 28th Division to the north, Barton’s men saw to it that the enemy’s cost in getting across the river was a heavy one. After taking heavy casualties, the Germans were forced to cross farther south at Edingen.

But once across the Sauer, the Germans quickly moved north and advanced on Echternach to surround it. Securing Echternach would keep a supply line open and allow for an expansion of the German bridgehead. In what would be comparable to a Luxembourg version of the fight at Bastogne, the Americans of the 12th Regiment were determined to hold onto Echternach or die in the effort.

Sensfuss’s men may have swept aside the American outposts and captured their mortars, machine guns, and antitank weapons, but they had not yet taken the town itself.

The Germans charged into Echternach only to encounter the men of Easy Company, who fought them tooth and nail in the streets. The sheer weight of German numbers, however, steadily drove the GIs back, and Easy Company’s survivors, under the command of Captain Paul DuPuis, secured a fallback position inside a hat factory and a few surrounding buildings in which they barricaded themselves.

A little north and farther west, Sensfuss was forced to bypass the town of Berdorf as 1st Lt. John L. Leake from Fox Company had some five squads (roughly 60 men), along with a .50-caliber machine gun and a Browning Automatic Rifle to support their efforts. They turned the three-story Parc Hotel and several stone buildings into a virtual “Alamo” and held out for four days despite accurate German shelling.

“No Retrograde”

Brandenberger had no armor; only his 5th Parachute Division had assault guns that his other units were counting on and awaiting their promised arrival. Brandenberger knew that the inevitable American counterattack would come from Patton and that would mean tanks.

Without assault guns or secured strongpoints to place them in, Brandenberger knew Patton’s armor would surely push the Germans across the Our and Sauer Rivers and back onto their home turf. Time was not on Brandenberger’s side, so his infantry would have to claw its way ahead and seize its objectives quickly.

The companies of Chance’s 12th Regiment were scattered in various nearby locations but holding firm. Able and George Companies were holding the roads to Lauterborn and Echternach open, while Fox Company continued to hold Berdorf and Item Company occupied Dickweiler. The GIs were barely maintaining their grip as Barton issued orders forbidding “any retrograde movement.”

There was some glimmer of hope on December 17 as the 42nd Field Artillery and the 12th Regiment’s own Cannon Company (105mm howitzers) provided much needed fire support to keep the Germans at bay. Also, the American 10th Armored “Tiger” Division was in Thionville, France, and was immediately ordered north to Luxembourg.

Separate from the 10th Armored, there were some additional 10 Stuart and eight Sherman tanks that were hastily pulled together and sent to assist the 12th Regiment. Finally, three hodgepodge armored/infantry task forces (Standish, Riley, and Luckett), along with some combat engineers, were Jerry-rigged to reenforce the desperate American defenders.

The task force under Lt. Col. J.R. Riley actually rolled into Echternach on December 18 and offered to take the men of Easy Company out of the stronghold they had established in the hat factory. Captain DuPuis declined, citing General Barton’s “no retrograde” order of two days prior. DuPuis pointed out that his men had sufficient ammunition—and a more than ample supply of wine.

Patton’s Line in the Snow

While Brandenberger was dealing with the inefficiencies of his Seventh Panzer Army, Patton’s Third Army could not have been more prepared for battle. After a bloody three-month siege, Patton had successfully captured the fortress city of Metz in Lorraine, France. Patton was especially puffed up by this victory—not only because he had snatched it from the jaws of defeat, but also because he was the first commander since Attila the Hun in ad 451 to conquer Metz. His Third Army was now resupplied, highly experienced, and highly motivated.

Patton set up his headquarters in Luxembourg City alongside 12th Army Group and the Ninth Air Force, which were already established in Luxembourg’s capital. Patton’s decision effectively drew a line in the snow, and he was not about to let the Germans cross it. Patton had suspected for some time that the Germans were ready and willing to execute a winter offensive and had anticipated approximately where they might strike. This allowed him to plan for a counterstrike.

One of the units that had been with Patton since the formation of Third Army was the 5th Infantry “Red Diamond” Division under the command of Maj. Gen. Leroy “Red” Irwin. The 5th was a part of XX Corps, which was often referred to by the Germans as Patton’s “Ghost Corps” because of its ability to suddenly appear out of nowhere and inflict great pain.

The 5th was often at the tip of Patton’s spear as he plowed through France. The men of the 5th had moved farther east than any American division in World War I and had been dubbed the “Red Devils” by the Germans in 1918. It would maintain that fearsome reputation in World War II.

When the Battle of the Bulge erupted on December 16th, the 5th was far to the southeast, engaged in intense street fighting in Saarlautern and struggling to gain control of the bridgehead over the Saar River that would take it right into Germany proper.

On December 21, the 5th was detached from Maj. Gen. Walton “Bulldog” Walker’s XX Corps and assigned to Maj. Gen. Manton Eddy’s XII Corps. It was to be sent northwest toward Diekirch to engage the Germans there and liberate the town.

The men of the 5th were loaded onto trucks, tanks, jeeps, or simply walked as they moved into Luxembourg without sleep or hot chow. Meanwhile, Patton would use his beloved 4th Armored Division, with the 26th and 80th Infantry Divisions in support, to swing wide to the left and make an end run to Bastogne to break through to the 101st Airborne.

“Kill the Sons-of-Bitches”

By December 21, the American situation in northern Luxembourg was becoming desperate. The Germans had overwhelmed the defenders in the Echternach hat factory the day before (the GIs there had been given permission to withdraw, but only two escaped while the rest were either killed or captured), thus securing Echternach and a lifeline across the Sauer for their comrades. Easy Company had gone down hard, but not without costing the Germans heavily in irreplaceable time and men. The 12th Regiment would later be awarded Luxembourg’s Croix de Guerre for its gallantry in the fighting.

The Americans had new worries as Brandenberger’s requested support started to appear. Northwest of Diekirch, near Goesdorf, the newly arrived Führer Grenadier Brigade was consolidating its position with infantry and some 90 armored vehicles. If all this wasn’t bad enough, the 79th Volksgrenadier Division showed up outside Diekirch to reinforce and invigorate the Führer Brigade in its operations. Both organizations had been battle hardened on the Eastern Front and were well accustomed to winter warfare.

Back toward the Sauer River and Echternach, the men of Sensfuss’s 212th Division were filled with blood lust and still on the march. They advanced south like an angry mob screaming, “Kill the sons-of-bitches!” in broken English. On the American side, the remainder of Chance’s 12th Regiment dug in while Task Force Luckett raced forward to plug the gap in front of the Germans’ 276th Division, where the Americans were hanging on by a thread.

Still, hopes among the GIs were high as XII Corps commander Manton Eddy set up his headquarters in Luxembourg City while Maj. Gen. William Morris was bringing up elements of his 10th Armored Division to assist; the 5th Infantry Division raced northward to join the battle. No one realized it yet, but the Germans had reached their high point in Luxembourg and the tide of battle, while slow and bloody, was soon to turn.

The Battle For Berdorf

On December 22, Patton had the piecemeal makings of a counterattack in the offing. The 10th Armored made up the left flank of a relief force pushing north toward Echternach, while the 10th Regiment from General Irwin’s battle-hardened 5th Infantry Division was moving on the right. Barton’s 4th, which had been engaged in a skillful defensive action that halted the German advance south of Echternach, was in the center.

The Germans could no longer advance southward but made good use of their artillery and nebelwerfers to push the Americans back every time they gained ground. The battle south of Echternach turned into a stalemate.

The following day the 2nd Regiment, also from Irwin’s 5th Division, relieved more of the beleaguered men of the 4th Division when it linked up with them in an open area outside Berdorf.

There was nothing to celebrate on Christmas Eve for the men of the 2nd Regiment as two of its three battalions were sent against the Germans just a few hundred yards north of Breitweiler and Consdorf. After eight hours of bitter fighting, the veteran Red Devils had advanced a mere 200 yards. They had entered a German kill zone and were bogged down by enfilading fire.

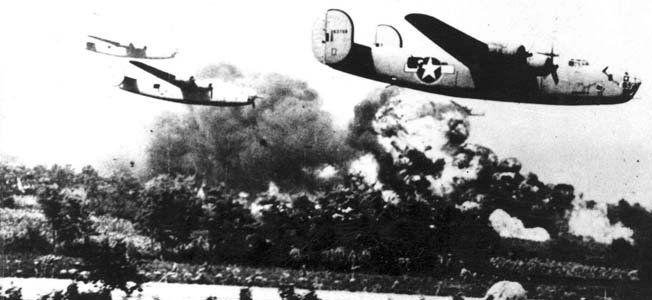

On Christmas Day, the fog lifted and American Republic P-47 Thunderbolt fighter-bombers sped to assist. One shot up a convoy of vehicles, including ambulances, along the roadway. The problem was that these vehicles were part of the 2nd Regiment.

The Germans hoped to exploit the situation by hitting the 2nd Regiment with a nebelwerfer rocket attack on Christmas night. The next day events shifted dramatically as the Americans, eager for payback, jumped off at 5 am and took the southern end of Berdorf, bagging over 100 prisoners before the enemy knew what hit them. The Germans in the north end of town made a ferocious counterattack with every form of heavy weapons—from mortars to rockets to artillery.

The Germans were also using the tactic of putting their own men in American uniforms. During a lull in the fighting, three men in American uniforms and coats were moving almost leisurely down a street in Berdorf when Sergeant Henry Lipski opened the door of a house occupied by GIs and yelled out, “Get off the street, you stupid bastards!”

The men soon revealed their true loyalties as they whipped out MP-40s from beneath their coats and fired in unison on Sergeant Lipski; he was dead before he hit the ground. The three Germans then made their escape around the corner of a house before the unbelieving Americans could even process what they had just seen.

Ettelbrück and Diekirch

The 2nd Regiment finally drove the Germans out of Berdorf on December 27, summarily executing three Germans captured in American uniforms. Irwin’s men were slowly pushing the enemy back. They would be sent farther west toward Ettelbrück with the objective of driving the Germans north and into Diekirch.

That portion of the battle became one of attrition as the infantry on both sides fought for control of the area between Ettelbrück and Diekirch. The Germans often held the high areas along steep embankments, and the Americans paid dearly whenever they tried to advance or move up along the slopes to clear the enemy.

The third and final regiment in Irwin’s division was the 11th, and it held the area on the left flank of the 2nd Regiment along the Schwartz Erntz River. Under the command of Colonel Paul Black, the men of the 11th Regiment made a two-mile advance and succeeded in dislodging German infantry from the high ground near Haller.

With the support of tanks from the 10th Armored Division, the 11th Regiment then severed the line between General Dempwolff’s 276th and Sensfuss’s 212th Volksgrenadier Divisions. It was a breach the Americans would exploit to the fullest in the commencement of a drive to push the enemy out of Luxembourg and back into Germany.

The 11th Regiment went on to surround Waldbillig and take Haller, where enemy POWs revealed orders for a German withdrawal. On the extreme right flank, the 10th Regiment from the 5th Division and the 8th Regiment from the 4th Division were clawing at the Germans on the outskirts of Echternach.

The Americans captured the high ground overlooking the Sauer River and used artillery to cut the German lifeline into Luxembourg and rain death down on Sensfuss’ prized 212th Volksgrenadiers. A false rumor spread among American ranks that 120 men from the 12th Regiment were still in Echternach, but when patrols found nothing in the village the men were officially listed as missing in action.

Caught in the middle of all this carnage were the civilians of Luxembourg. Unable to extricate themselves in time, they had to remain holed up in cellars or attempting to dodge crossfire in the streets. Napalm dropped from P-47s along with white phosphorous in 81mm mortar rounds often burned their homes to the ground. There was minimal access to food or medicine, and many civilians simply died from exposure, hunger, stress, and want of care. To add to the overall misery and mortality of soldier and civilian alike, the winter of 1944-1945 was the coldest in Europe in a century.

Truce at Bilder

With Echternach and Berdorf back in American hands and Ettelbrück secure, the lines stabilized. Heavy snows and bitter cold forced an unofficial truce as men on both sides huddled around open fires, more worried about the elements than the enemy. Frostbite and trench foot took additional heavy tolls on both sides.

There was still excitement and danger. Pfc. Michael Bilder of the 2nd Regiment was sent into Echternach on a supply (booze) run. At a tavern in the town, Bilder was conversing with the bartender as three GIs casually strolled in, hung their helmets on a hook, and sat down at a table. The bartender excused himself, and a few moments later American MPs simultaneously burst through both the front and rear doors, taking the three soldiers at the table into custody.

A stunned Bilder asked the bartender what had just happened. “Those men were Germans,” the bartender explained. “I knew it almost immediately after they entered,” he added. “American soldiers always slide their helmets under their chairs after they sit down, but Germans always hang them on hooks before they seat themselves.” The three Germans in American uniforms were summarily shot.

Goldknapp Hill

The unofficial truce for Bilder and the others in the 2nd Regiment ended in mid-January when enough time had passed for the Americans to be resupplied and reinforced. The time had come to cross the Sauer River below Diekirch and retake the town.

The plan called for a stealthy crossing in the dead of night, but events would soon reveal that the plan would be anything but stealthy. At 3 am on January 18, 1945, the temperature was well below zero as riflemen from the 2nd Regiment waited for engineers to throw a footbridge across the relatively narrow river. German snipers picked off the continuing supply of engineers with ease until the American command had had enough. The word was given for the GIs to cross the river in M-2 assault boats. The rifle squads of the 2nd Battalion dutifully picked up their 400-pound wooden assault boats and ran through mind-numbing cold in knee-deep snow toward the Sauer.

The Germans illuminated the darkness with flares that cut through the fog as they fired their heavy machine guns at the GIs starting across. The 914th Regiment of the 352nd Volksgrenadier Division was on the high ground (Goldknapp Hill) trying to prevent the American crossing.

Smoke was released to mask the GIs’ advance, and the 3rd Battalion opened up to provide covering fire. The men in the 2nd Battalion, with enemy fire to their front, American fire to their rear, and almost no visibility at all, had to show extreme discipline and nerves of steel as they remained in their designated area for the crossing.

Once arriving on the opposite bank, the Americans snagged wires that set off trip flares to further alert the Germans to their presence as a withering fire reigned down from above.

Meanwhile, the 3rd Battalion jumped into boats and followed across. American artillery then opened up to break enemy strongpoints on Goldknapp Hill, and the GIs were mobile once again.

The 2nd Battalion advanced up Goldknapp Hill to rout the Germans as the 3rd swung right to take Ingledorf and advance on the outskirts of Diekirch. Crossing the Sauer near Diekirch had been costly. The Americans had 17 dead, 81 wounded, and 30 missing (probably killed). The casualties equaled almost a company.

Taking No Prisoners

The Germans were not yet through impersonating Americans. On January 19, American troops coming back from patrol outside Diekirch were huddled around a fire burning inside a steel drum when three men in American uniforms approached in the darkness. They quickly drew MP 40s from behind their backs and began to spray lead.

Sergeant Hymen Stein was wounded, but the other Americans quickly composed themselves and returned fire. Sergeant Stein made a fatal error in judgment when he decided to try and crawl to an area of greater cover. The Germans finished him off and then quickly withdrew.

Brutality sometimes extended to both sides. After another massacre of Americans, Michael Bilder recalled, “Word filtered into us from the 10th Regiment after they took Bastendorf on January 19 that the Germans in that town had executed American POWs from the 28th Infantry Division who’d been captured in the early days of the Bulge. Typified by the massacre at Malmedy [Belgium], this kind of news caused a great deal of hard feelings among American units, but it seemed to affect some of our men in the 5th Division particularly strongly.

“After word got out that American POWs had been killed, a number of our guys became a lot less likely to offer quarter to any surrendering Germans, and the enemy quickly picked up on our change of attitude.”

Bilder noted that later during the Bulge, “Killing prisoners was never officially permitted, but sometimes a blind eye and deaf ear were turned towards it. If we had to move up quickly and had taken prisoners before we reached our final objective, those prisoners were in trouble if we couldn’t spare anyone to stay behind and guard them. Someone was expected to lag behind for a moment or two to do the dirty work. It was never an order, or even mentioned. It was simply understood.

“This was not a matter I ever had to struggle over. Someone who had just lost a close buddy or simply enjoyed killing always stepped forward to do the job. In retrospect, somebody, including me, should have objected, but in battle all the rules of heaven and earth become casualties of war.”

Pushing the Germans Out of Luxembourg

A seesaw battle for Diekirch took place in which the center of town changed hands four times before shells from American 155mm guns drove the Germans out. The Americans had taken 45 prisoners from the 208th Volksgrenadier Regiment. They were lucky to be spared, for in the center of Diekirch were the bodies of six American POWs who had been shot execution style in the back of the head. There were also more than a dozen civilians who had been shot and their bodies piled in the town square because they had openly welcomed their American liberators.

There was some payback as the civilian populace identified the collaborators in their midst. The women immediately had their heads shaved while the males were taken by the Luxembourg resistance into a wooded area outside town to have their service to the Germans repaid in kind.

Farther to the west, on the 5th Division’s left, the 80th “Blue Ridge” Infantry Division was advancing across rough terrain against a German army already in retreat. The major concern for Model and Brandenberger now became saving the German Seventh Army from being trapped and subsequently destroyed.

Things were suddenly looking very bad for the Germans. Along the far western boundary of Luxembourg, the American 26th “Yankee” and 90th “Tough Hombres” Infantry Divisions had moved on Wiltz and were driving back the German 5th Parachute Division, which had overextended its supply lines and had been without relief.

A lesson not to be forgotten, in Luxembourg as well as in all of Europe, was that the Germans most often inflicted their greatest casualties against their enemies while in retreat; the advancing Americans would have to keep their guard up.

Model directed the Panzer Lehr and 2nd Panzer Divisions from Belgium to cover the Seventh Army’s retreat. Raging snowstorms slowed the advance of the GIs of the 4th and 5th Infantry Divisions, but it was only a band-aid for Brandenberger’s hemorrhaging of men and ground. By January 20, the American forces in Luxembourg were linked, rearmed, resupplied, in command of the heights, and ready to continue their attack.

The weather cleared on the 22nd, and American P-47s once again pounded the enemy, shooting up the German columns along the roads to Vianden. Brandenberger’s Seventh Army may have escaped encirclement, but it certainly did not escape destruction. By January 28, the American III and XII Corps had linked up, reconnecting the link between Belgium and Luxembourg, and in a little over a week the Germans were pushed out of Luxembourg altogether.

This article represents but a small fragment of the overall desperate fighting that took place in Luxembourg; scores of cities, towns, villages, hamlets, clusters of farm buildings, roads, bridges, and open fields became battlefields where dramatic life-and-death scenarios were played out with extreme violence; it is impossible within the scope of this short article to fully explore, or even mention, all of the many other actions that raged there from mid-December 1944 through January 1945.

For the Germans, Hitler’s colossal gamble in the West had failed, and following that failure would come the apocalyptic defeat of Nazi Germany. There would be little respite for the Germans after the battle, as Patton would send the 5th Division across the Sauer and into Germany on February 7.

Still, the exceptional courage of a weary but determined group of defenders and a relief effort that refused to be slowed by the elements or the enemy played no small role in ensuring that the Battle of the Bulge would be forever remembered as an American victory that hastened the defeat of Nazi Germany.

My father was a 1st Lt with the 419th Armored Field Artillery Battalion of the 10th Armored Division. His battalion defended the southern part of the German offensive along the Luxembourg border. It is rather amazing to me how anyone could keep track of who was where in all this process.

The US “citizen soldier” out paced and out fought its Tuetonic adversary…

The Germans achieved a total surprise attack on the morning of 16 December 1944, due to a combination of Allied overconfidence, preoccupation with Allied offensive plans, and poor aerial reconnaissance due to bad weather. American forces bore the brunt of the attack and incurred their highest casualties of any operation during the war. The battle also severely depleted Germany’s armored forces; they remained largely unreplaced throughout the war. German personnel, and, later, Luftwaffe aircraft (the concluding stages of the engagement ) had also sustained heavy losses. The Germans had attacked a weakly defended section of the Allied line, taking advantage of heavily overcast weather conditions that grounded the Allies’ superior air forces. Fierce resistance on the northern shoulder of the offensive, around Elsenborn Ridge, and in the south, around Bastogne, blocked German access to key roads to the northwest and west that they counted on for success. Columns of armor and infantry that were supposed to advance along parallel routes found themselves on the same roads. This, and terrain that favored the defenders, threw the German advance behind schedule and allowed the Allies to reinforce the thinly placed troops. The farthest west the offensive reached was the village of Foy-Notre-Dame, south east of Dinant, being stopped by the U.S. d Armored Division on 24 December 1944.

I enjoyed the article, but being from North Carolina, you should have mentioned the 30th Division. Their ability to hold off the northern German attack was difficult but often left the German units destroyed or badly damaged. That’s not to say the 30th didn’t have trouble, but, as they did all through the war, they were detested by the Germans, and the radio lady for the Germans called them Roosevelt’s SS. That nickname will stick to the 30th (A National Guard Division originally) and will be part of the reason they were chosen as the best US infantry division in the battles of 1944-45. For those of you who become interested in this, I would suggest Robert Baumer’s Old Hickory: 30th Division, top ranked infantry division in Europe in WWII. Thanks for putting up with my note. I mean no harm to all the other great divisions. It’s just that the 30th often goes unnoticed in many WWII books (or barely notices)