By Eric Niderost

On a gloomy Friday morning, September 26, 1777, an advance party of the British Army marched into Philadelphia to take possession of the city. It had rained the night before, and dark clouds still lingered overhead to somewhat dampen the invaders’ self-congratulatory triumph. Philadelphia was the capital of the infant United States, now struggling to gain its independence from Great Britain, and its capture had been long anticipated. Local loyalists to the crown, called Tories, ardently hoped that the revolution and its supporters—fellow citizens or not—had been dealt a major blow by the forces of the king.

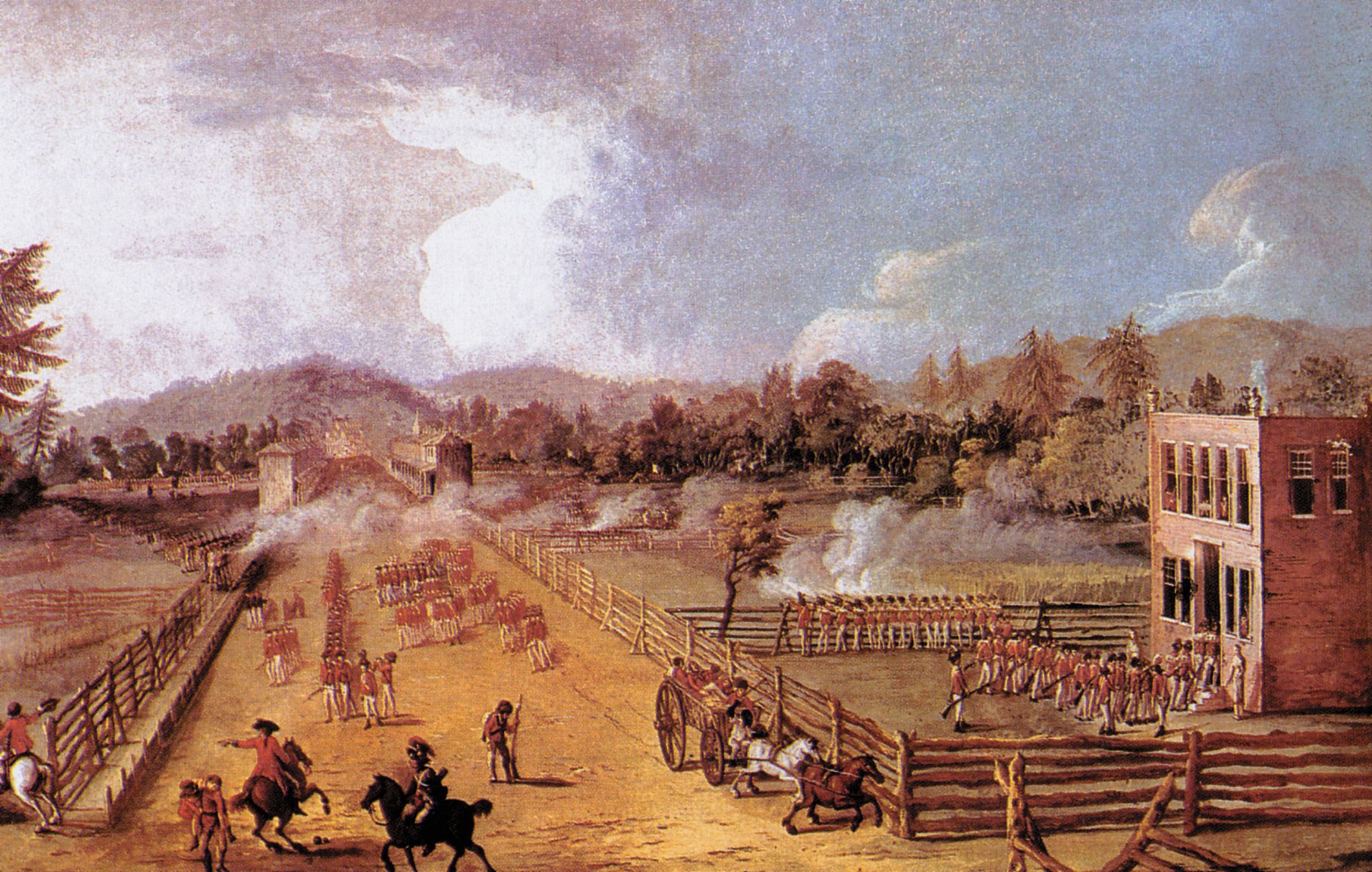

The 3,000 British and Hessian troops marched into town along the Germantown Road, then advanced down Second Street, a short distance from the Delaware River. Philadelphia was the largest city in America, boasting some 34,000 people, and its stately red brick homes and well-maintained streets were the pride of its citizens.

Now the straight-as-an-arrow thoroughfares echoed with the tramp of parading British soldiers. A smartly dressed contingent of dragoons led the way, guided by local Tories Enoch Story and Phineas Bond. A regimental band came next, the musicians wearing the reversed colors of their regiment. Army commander Maj. Gen. Lord Charles Cornwallis appeared, surrounded by a knot of British and Hessian aides. He cut a magnificent figure, his scarlet uniform fairly dripping with gold braid, and as he made his way through the streets he acknowledged the cheers of the crowd with a self-satisfied mixture of grace and dignity.

The main body of soldiers followed the general, rank after rank of British and Hessian grenadiers. These were elite troops, and they looked the part. The grenadiers were all tall men, their height made even more imposing by their towering black bearskin caps. Brick red coats sported shoulder wings, symbols of their special status, and breeches had been pipeclayed to immaculate whiteness to hide the stains of a hard campaign. The Hessians, German mercenaries in the pay of the British crown, were dressed, Prussian-style, in blue coats, tall brass-fronted miter caps, and long queues that hung down their backs. An awed Philadelphian noted their “terrific mustachios,” which gave the men a fiercely Teutonic appearance. Another regimental band came along behind them, drummers beating a lively tattoo, and a motley collection of baggage wagons, pack animals, and female camp followers brought up the rear.

The British troops filed past Elfreth’s alley, where local artisans made their home, and Christ Church, a magnificent Georgian building whose 200-foot-high steeple was a familiar city landmark. Then, as if by design, the clouds parted and the scarlet flood turned into Chestnut Street and proceeded to the Pennsylvania State House. Fourteen months earlier, the Declaration of Independence had been adopted in this very building. Now the birthplace of the revolution was in British hands.

The sun’s rays brightened the soldiers’ red coats and sparkled off musicians’ instruments as they played “God Save the King.” The music was a not-too-subtle political statement, a clarion call for Philadelphians to renew their loyalty to the crown. To the victory-flushed Englishmen, the whole city seemed to have turned out to greet them with thunderous applause and rousing cheers.

The tumultuous welcome seemed a particular vindication for General Sir William Howe, commander in chief of British land forces in America and author of the Philadelphia campaign. Howe was convinced that Pennsylvania was a hotbed of latent loyalism. If he could capture and hold the state’s leading city, he would deal the revolution a powerful if symbolic blow, while at the same time encouraging untold numbers of Pennsylvania Tories to come out of hiding and flock to the king’s banner.

Secretary for the American Colonies Lord George Germain granted permission for Howe to set off on his Philadelphia quest from his headquarters in New York City, even though Germain knew that General John Burgoyne was planning a major offensive from Canada at the same time. In theory, Howe was supposed to support Burgoyne’s invasion of upstate New York from the south, but poorly worded exchanges between Germain and his headstrong subordinate only muddied the waters and kept the men’s intentions confused and contradictory.

Howe compounded the difficulties by choosing to travel to Philadelphia by sea. The general’s communications with Burgoyne, tenuous at best, would be completely severed by long weeks of sailing down the coast of New Jersey and up the Chesapeake Bay with a ponderous armada of some 267 ships. Germain’s inability to control Howe, coupled with the many weeks it took to funnel orders across the Atlantic, added to the command confusion. Still, in the short term, everything seemed to go Howe’s way. On September 11, the British general defeated George Washington at the Battle of Brandywine, 25 miles southwest of Philadelphia, where Washington had attempted to block the British advance. Despite being outmaneuvered and outgeneraled, the wily American commander managed to stabilize the situation and withdraw to Chester, Pa., before his army was completely destroyed.

Giving Washington the Slip

After two more weeks of constant maneuvering and countermaneuvering, Howe gave Washington the slip, feinting toward Reading and then backtracking to cross the Schuylkill River by means of a pontoon bridge.

The way to Philadelphia was now open. Washington, for his part, had more on his mind than a single city, even if it was the fledgling nation’s capital. The Pennsylvania counties west of Philadelphia were home to half the colonies’ vital iron industry, and Reading was the Continental Army’s main supply depot. These areas had to be protected at all costs, and Washington was not about to let Howe take Philadelphia unmolested and then threaten the entire region.

Washington dispatched Brig. Gen. “Mad” Anthony Wayne to harass the British as they approached the capital. Tired of the incessant skirmishing, Howe decided to teach the Americans a lesson they would never forget. On the morning of September 21, Maj. Gen. Charles Gray surprised Wayne’s men at Paoli Tavern, 20 miles west of Philadelphia.

When the British attacked at 1 am, Wayne’s Pennsylvanians were literally caught napping. The Continentals were in the process of rousing themselves for their own night march, groggily making breakfast in front of crude makeshift shelters. The British surprise was complete, helped by the fact that Wayne had done a shoddy job of sending out pickets to guard against just such an attack.

The British 2nd Light Infantry Battalion went in with the bayonet, driving the befuddled colonials before them. Rampaging British infantry swept through the American camp like furies, running through all they encountered. Some Pennsylvanians were stabbed as they tried to surrender, and huts were set ablaze with Americans still inside. Another 71 Americans were taken prisoner.

For many Pennsylvanians, the “Paoli Massacre” was a humiliation that had to be avenged. In American eyes, the British were no better than “bloodhounds,” slavering and bloodthirsty beasts. The Pennsylvanian brigades were determined to pay back the British in kind.

Despite the Paoli incident, Philadelphia seemed to welcome the British, but the approbation was more apparent than real. Thousands did line the narrow streets to watch the grenadiers parade past, but on closer inspection most of the crowd consisted of women and children. In the days immediately preceding the British occupation, perhaps a third of the city’s inhabitants—around 10,000 people—had fled the city.

Sally Bache, Benjamin Franklin’s daughter, was one of the refugees. Franklin himself was in Paris, serving as American envoy to the French court, and in his absence Sally took care of his house near High Street. She narrowly escaped with her five-day-old daughter and a few possessions she managed to salvage on such short notice. British officers took up residence in many of the city’s finest homes; Major John Andre lodged in Franklin’s house.

Only about 4,482 males over the age of 18 remained in Philadelphia, most of them hardcore loyalists or disaffected Quakers who loathed the revolution on pacifist grounds. Hundreds of houses were left vacant, their owners having joined the Patriot exodus. Howe’s original reason for taking Philadelphia—to encourage the “thousands” of Tories to rally behind the British cause—was largely an illusion. Few Pennsylvanians, in Philadelphia or elsewhere, renewed their loyalty to the crown.

Besides being a victim of self-delusion, Howe had other, more pressing concerns on his mind. He controlled the rebel capital, but what was he going to do with it? Supplying the city would be a problem, since the Pennsylvania state navy and several rebel forts blocked the lower Delaware River and British access to the sea. Howe’s most immediate problem was how to defend his hard-earned prize.

The British Royal Engineers wasted no time in surveying the ground just north of the city. Philadelphia was essentially a peninsula, flanked on the west by the Schuylkill River and on the east by the Delaware River. These waterways were protective buffers, natural moats, but the city was still vulnerable to attack from the north. To guard against this, Howe’s sappers worked their shovels with a will, busily erecting a line of earthen redoubts from Kensington on the Delaware to Fairmont Hill on the meandering Schuylkill. Until the redoubts were completed, Howe based the bulk of his army in Germantown, a tiny farming community eight miles north of Philadelphia. Many of the state’s settlers were indeed German, sturdy Teutons from the Palatinate attracted by Pennsylvania’s heady mixture of religious freedom and rich soil. In recent decades, prominent Philadelphians had begun to build country houses at Germantown, rural summer retreats from the disease, stench, and sweltering heat of the city.

While Howe was busy preparing his defenses, George Washington was biding his time, waiting for the right opportunity to resume the offensive. Although he was often bested in battle, Washington had a keen sense of strategy and a vision for the future that was truly continental in scope. He immediately realized that Howe had made a major blunder by failing to support Burgoyne in New York. If Washington could defeat Howe before his defensive redoubts were finished, he might even trap the British army within the confines of Philadelphia. The city would become its captors’ own prison.

For the time being, the Continental army was resting and refitting after weeks of hard campaigning. The men were tired, their uniforms dirty, patched, and in tatters. A thousand men—maybe more—lacked decent footwear, prompting Washington to write plaintively that “our distress for want of shoes is almost beyond conception.” Yet, paradoxically, American morale had never been higher. Brandywine had been a tactical defeat, but the men were proudly conscious of having given the elite British a bloody nose in the process. The American units had performed exceptionally well, standing up to the heaviest punishment the British could mete out. The Continentals were becoming a disciplined fighting force in their own right.

The Fabled “Black Watch” Sent to Chester from Germantown

On October 2, a British courier was captured with dispatches revealing that the British 10th Foot and 42nd Royal Highlanders, the fabled “Black Watch,” were being sent to Chester from Germantown. This force totaled 1,000 men. Two thousand more had been dispatched to Wilmington, Del., to help in the ongoing operations to capture the rebel forts along the Delaware River. Howe’s numbers were further reduced by the 3,000 grenadiers who garrisoned Philadelphia under Cornwallis. These deductions did not include the soldiers who were sick or recuperating from wounds sustained at Brandywine. This left Howe with an effective force of only around 8,000 men. If Washington could muster his own forces and attack without delay, the Americans would enjoy a rare numerical advantage.

Washington’s army soon swelled to 11,000 men, more than enough to do the job. The general was optimistic, athough nearly a quarter of his force—some 3,000 men—were state militia of dubious quality.

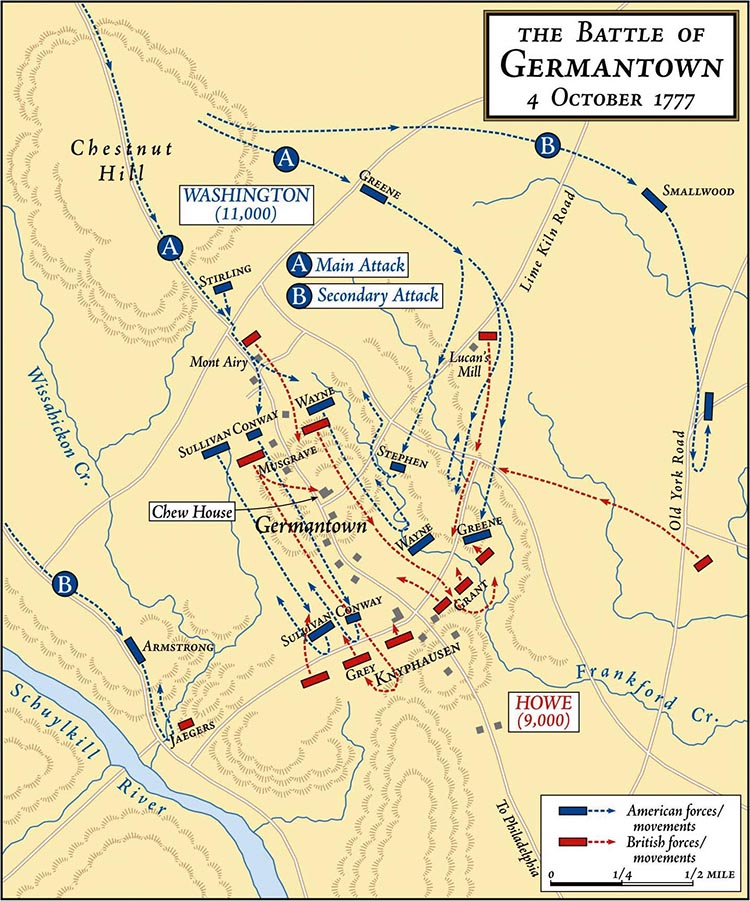

Acting quickly, Washington devised a brilliant if complex plan, striking in its sheer audacity. Not one but four columns would converge on the British camp at Germantown. Two columns of Continental regulars would hit the enemy center with overwhelming force, driving in the screen of pickets before coming to grips with the main enemy force. The right and left flanks of the British position would be attacked simultaneously by militia units from New Jersey, Maryland, and Pennsylvania.

Meanwhile, a small force of irregular troops, in essence a fifth column, would march down the west bank of the Schuylkill River to Middle Ferry. Strictly a diversion, these men would distract the grenadiers inside Philadelphia and prevent them from joining the main body of British troops at Germantown.

It all seemed straightforward on paper, but there were many potential problems of execution. It was going to entail a night march, with some units still many miles from their assigned start positions. The whole scheme demanded clockwork precision—and a good deal of unpredictable luck.

In the meantime, the British army was camped at Germantown, oblivious of the impending attack. For the veteran soldiers, it was now simply a matter of waiting for the engineers and hard-working sappers to complete their line of defensive redoubts. Once that was done, the redcoats could retire behind them, safe and secure. The British looked forward to a peaceful hibernation, spending the winter sampling the occupied city’s civilized delights.

The bulk of Howe’s army was camped in a line that ran about three miles from Van Deering’s Mill on the Schuylkill River along School House Lane and Church Lane to Luken’s Mill.

The 2nd Battalion, British Light Infantry, was posted at Mount Pleasant, a small rise of ground about two miles from the main encampment. They were the eyes and ears of the British army, ready to give warning should the need arise. About 400 yards farther north, near Mount Airy, the country house of a local Philadelphia merchant, a screen of light infantry pickets kept watch. Two six-pounder cannon were also on hand, their Royal Artillery gunners ready to repulse any surprise enemy attack.

The British light infantrymen were accustomed to dangerous assignments, but the circumstances surrounding this current post were particularly troubling. The 2nd Light Infantry had taken part in the Paoli massacre, and they knew that the Continentals—particularly the Pennsylvanians—were thirsting for revenge. One of their officers, Lieutenant Martin Hunter, later recalled, “I don’t think our battalion slept very soundly after that night [at Paoli].” Lt. Col. Thomas Musgrave’s 40th Regiment of Foot was stationed at Cliveden, a mile behind the 2nd’s advanced positions. Cliveden, the estate of Pennsylvania Chief Justice Benjamin Chew, was admirably located in a central position that would allow Musgrave to support the 2nd Battalion at Mount Pleasant or the 1st Battalion a mile east near the crossroads of Limekiln Pike and Abington Road.

Washington’s Preparations Complete

On October 3, Washington’s preparations were complete. The brunt of the fighting would be borne by Continental regulars. The right-center column would be led by Maj. Gen. John Sullivan’s division, followed by Wayne’s Pennsylvanians. Sullivan had orders to drive down the Great Road, the main thoroughfare into the town. Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene’s left-center column, the strongest American force, was to attack down Limekiln Pike, just to the east of Sullivan’s forces.

Militia units were assigned the right and left flanks of the American assault. On the right, Brig. Gen. John Armstrong’s Pennsylvania militia was to turn the British left and pin it against the Schuylkill River. On the left, Brig. Gens. William Smallwood and David Foreman and their respective Maryland and New Jersey militias would move along the Old York Road in hopes of enveloping the British rear.

Washington’s ambitious scheme began to unravel at once. It took valuable time to sort things out and get men on the road. Some units were on the march at 6 pm, while others did not start the trek until 9 or later. The moon’s pale beams were blocked by thick layers of clouds, plunging the countryside into almost total darkness. The troops tucked slips of white paper into their hats in a vain effort to see each other in the dark. The night was chilly, and the dank, clammy air clung to the men like an enveloping shroud as they stumbled their way toward Germantown. Around 2 am, some Americans were captured by a British 1st Light Infantry picket. One of the prisoners was overly talkative, blurting out much of Washington’s battle plan, but when he was taken back to Philadelphia under guard he was not fully interrogated. Some British units were ordered to “alert and accouter,” but unaccountably the word did not go to Musgrave’s 40th Foot or to the 2nd Battalion of Light Infantry. It was a glaring, potentially fatal omission.

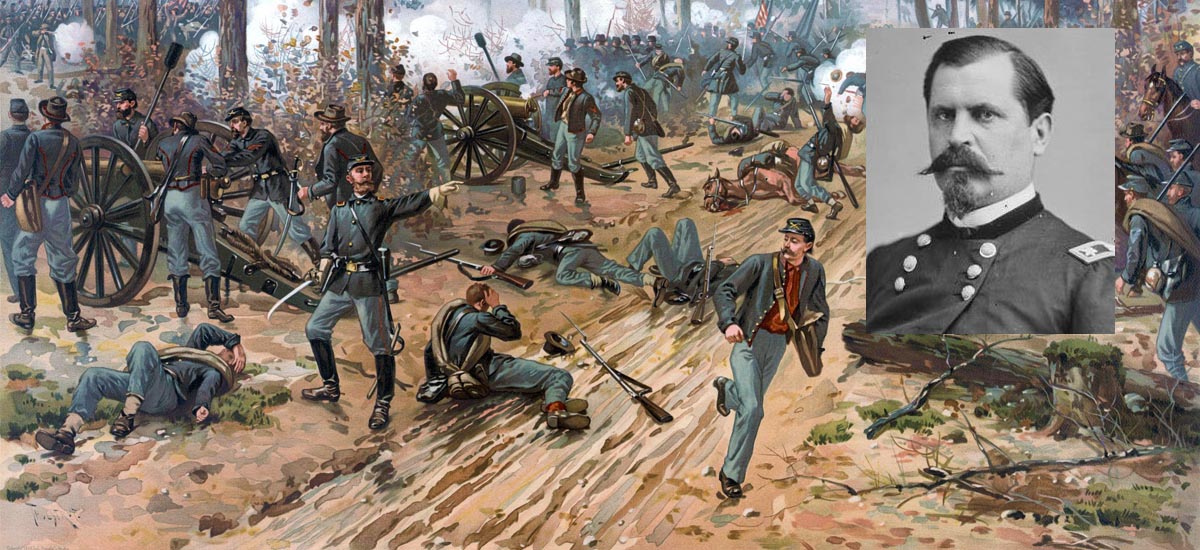

The Battle of Germantown began around 5:30 am on October 4, when the lead elements of Washington’s right-center column fell on the British pickets at Mount Airy. The tip of the thrusting American spear was Lt. Col. Josiah Harmar’s 6th Pennsylvania Regiment of the Continental Line. Many of these men were locals, and some even hailed from Germantown itself. They advanced in column, followed by the rest of Brig. Gen. Thomas Conway’s brigade, muskets leveled and bayonets fixed. The Americans surprised the British pickets, but the red-coated sentries managed to fire a few warning shots before falling back. The crack of Brown Bess muskets was accompanied by the deep-throated roar of two Royal Artillery cannons posted nearby. The British gunners also managed to fire off a few rounds, then abandoned their pieces to the advancing Colonials.

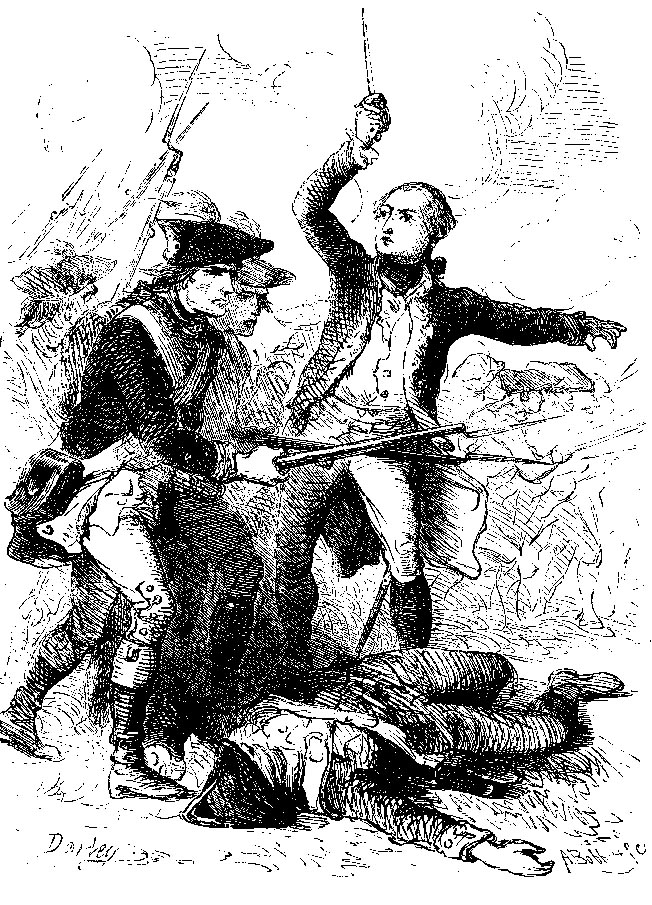

Dawn broke as Conway’s men moved forward against the 2nd British Light Infantry. For a brief, heartstopping moment the sun’s rays brought everything into high relief: the skeins of brown- and blue-coated Continentals advancing with grim determination, shouting, “Have at the Bloodhounds! Avenge Wayne’s affair!” The Americans halted for a moment, leveled their muskets, then fired a volley into the British infantry’s hastily forming ranks. Some of the redcoats, distinctive in their leather caps, fell dead or wounded as the shower of American lead peppered their ranks. But the light infantry troops were tough, well able to respond in kind. Officers barked commands, and privates’ muskets leveled in unison. Gouts of flame erupted from British barrels, the volley followed by a lusty “Hurrah!” and a hot-eyed bayonet charge. Conway’s men fell back in disorder, but the tables were turned again when more American units entered the fray.

British buglers sounded retreat, and the light infantrymen responded with sullen reluctance—the only alternative was annihilation. Pockets of British light infantry slowed the American advance, using fences and trees for natural cover, but the Continental advance was relentless. The orderly retreat quickly became a panicky rout.

“Form! Form! It’s Only a Scouting Party!”

When the fighting broke out, General Howe was at his headquarters in Stenton Mansion, north of the city. Quickly mounting his horse, Howe rode up the Germantown Road toward the fighting. Progress was slowed by the ever-growing flood of light infantrymen running in the opposite direction. Howe, himself a former light infantryman, was by turns incredulous and appalled. “For shame, for shame, Light Infantry!” he cried. “I never saw you retreat before! Form! Form! It’s only a scouting party!”

Seconds later a blast of American grapeshot slammed into a nearby tree, lacerating its trunk and raining down leaves on the general’s head. Howe was no coward, but he was also no fool. He quickly turned his horse around and joined the red-coated stream of fugitives. This was a major enemy offensive, not a raid or scouting party, and the light infantrymen were fully justified in their retreat.

As the battle progressed, more and more Continentals joined the fight. At times it was difficult to keep formations properly aligned because of fences and other man-made or natural obstructions. Conway’s men were still the leading edge of the American attack, but Sullivan’s Marylanders were right behind them, just west of Germantown Avenue on Allen’s Lane. Wayne’s Pennsylvanians were to the east of Germantown Avenue in close support. The Pennsylvanians were giving no quarter, bayoneting any British soldiers who had the fatal misfortune to fall into their hands. Officers tried to stop them, but they were bent on revenging the Paoli Massacre and, as General Wayne reported later, they “were not to be restrained for some time—at least not until great numbers of the enemy fell by our bayonets.”

Lieutenant Colonel Musgrave had formed the 40th Foot immediately after the sounds of firing reached his ears. He was an experienced soldier, literally a battle-scarred veteran. Earlier in the revolution, at White Plains, NY, he had received a wound that tore out a piece of his cheek. For a career soldier like Musgrave, the disfigurement was a badge of honor, an outward sign of inner toughness and resolve.

Now, refusing to panic, he sent part of his command forward to support the light infantry’s withdrawal, while the rest stayed behind at Cliveden to await further developments. The sounds of musketry grew ever louder, and Musgrave realized that Wayne’s avenging furies were already on Cliveden’s grounds, infiltrating the 40th’s encampment a few yards away. There was not a moment to lose. Musgrave ordered his men to retire to Cliveden mansion and barricade themselves inside.

Once his 120 men were safely inside, Musgrave ordered the shutters to be closed and the doors locked. Closing the windows plunged the ground floor into a cave-like darkness. On the second floor, redcoats poked their muskets out of windows, shooting at any target that presented itself. A few shots were exchanged with Sullivan’s and Wayne’s men, but the onrushing Americans quickly bypassed the house and moved on. They were after bigger fish: the main British army just down the road.

The Calm Before the Storm?

Musgrave knew that this was literally the calm before the storm, and he gave a short speech of encouragement to his men. He told them that their situation was by no means bad, and that they would be delivered soon by their comrades. Musgrave concluded that, in any event, they must sell themselves as dearly as possible to the enemy.

Washington and his staff were just behind Sullivan’s and Wayne’s advancing men. Washington halted in the vicinity of Billmeyer House on the Great Road, near the intersection of Germantown Avenue and Upsal Street. Although in the rear of his troops, Washington’s position was still a dangerous one. As if to underscore that danger, a British six-pounder cannonball sailed over the general’s head, then plunged to earth in a graceful but deadly arc. It smashed into a signpost, then ricocheted into Brig. Gen. Francis Nash, who just then was bringing his North Carolina troops into the fray.

The iron sphere smashed into his horse’s neck, then tore open Nash’s left thigh before mortally wounding Major John Witherspoon, son of Declaration of Independence signer John Witherspoon. Nash’s mount went down, partially pinning the wounded general in the process. He was quickly extricated from the tangle of saddle, reins, and dead horseflesh and sent to the rear on a stretcher. His thigh a mass of bloody flesh and bone, Nash mastered his pain to urge his men on. He later died of his wounds.

The situation was fluid and confusing. Sullivan’s Marylanders and Wayne’s Pennsylvanians were disoriented by the increasing fog, which was worsened by the gray-white clouds of powder smoke produced with each musket volley. Red-coated ranks became ghostly pink smears, and men fired at trees and other shadowy objects. The British were equally disoriented.

Washington was concerned not to hear the sounds of firing on the left, where Nathanael Greene was supposed to be launching the main attack against Germantown. As it happened, Greene had been delayed when his left wing guide lost his way. Worriedly, Washington scanned the horizon with his telescope. In the distance he could just make out Cliveden’s imposing bulk, but the rest of the battlefield was a shapeless, gray void.

The Continental commander in chief also worried that Sullivan’s men were expending ammunition at a prodigious rate. If this kept up, Sullivan’s troops would have little firepower left for the inevitable British counterthrust. Motioning his aide, Colonel Timothy Pickering, to his side, Washington said, “I am afraid General Sullivan is throwing away his ammunition. Ride forward and tell him to preserve it.” Pickering accomplished his mission without any problem, but as he rode past Cliveden a few stray musket balls whizzed past him—British troops were inside the mansion.

Pickering ordered Colonel Thomas Proctor of the 4th Continental Artillery to place his six-pounder guns in front of Cliveden at a position just across from the Germantown Road. In the meantime, Pickering rode forward to tell Washington that the great stone mansion was occupied by the enemy.

Washington listened intently to Pickering’s surprising news, then asked his assembled officers for their opinions. The general valued all advice, and even junior aides were encouraged to speak their minds. Pickering felt that a regiment should surround Cliveden, bottling up the British soldiers.

If they were ignored, he warned, they might sally forth and create havoc in the American rear. On the other hand, if they were surrounded they would be effectively neutralized, bottled up and prevented from doing further mischief. It was a sound argument, and Washington was inclined to agree. Most of his aides, including young Captain Alexander Hamilton, also agreed with this assessment. General Henry Knox was the only dissenter and, unfortunately for the Americans, his opinion carried weight. The portly bookseller turned artillery general prided himself on his formal knowledge of the rules of war, and according to classical theory, he said, it was “unwise to leave a fortified castle in the rear.” Knox insisted that Cliveden must be reduced by artillery fire, but the British should first be allowed to surrender. Against his better judgment, Washington let Knox have his way.

First Cannonballs at 7 A.M.

Lieutenant Colonel William Smith of Virginia volunteered to carry the American surrender demand under a flag of truce. Smith did not get far before a British musket ball bit into his leg. He was dragged to safety and evacuated to the main camp at Pennypacker’s Mill, but later died of his wound. Once more the Americans were infuriated by the enemy’s complete disregard for the proper rules of war, Smith’s death must be avenged. The second and bloodiest phase of the battle for Cliveden was about to begin.

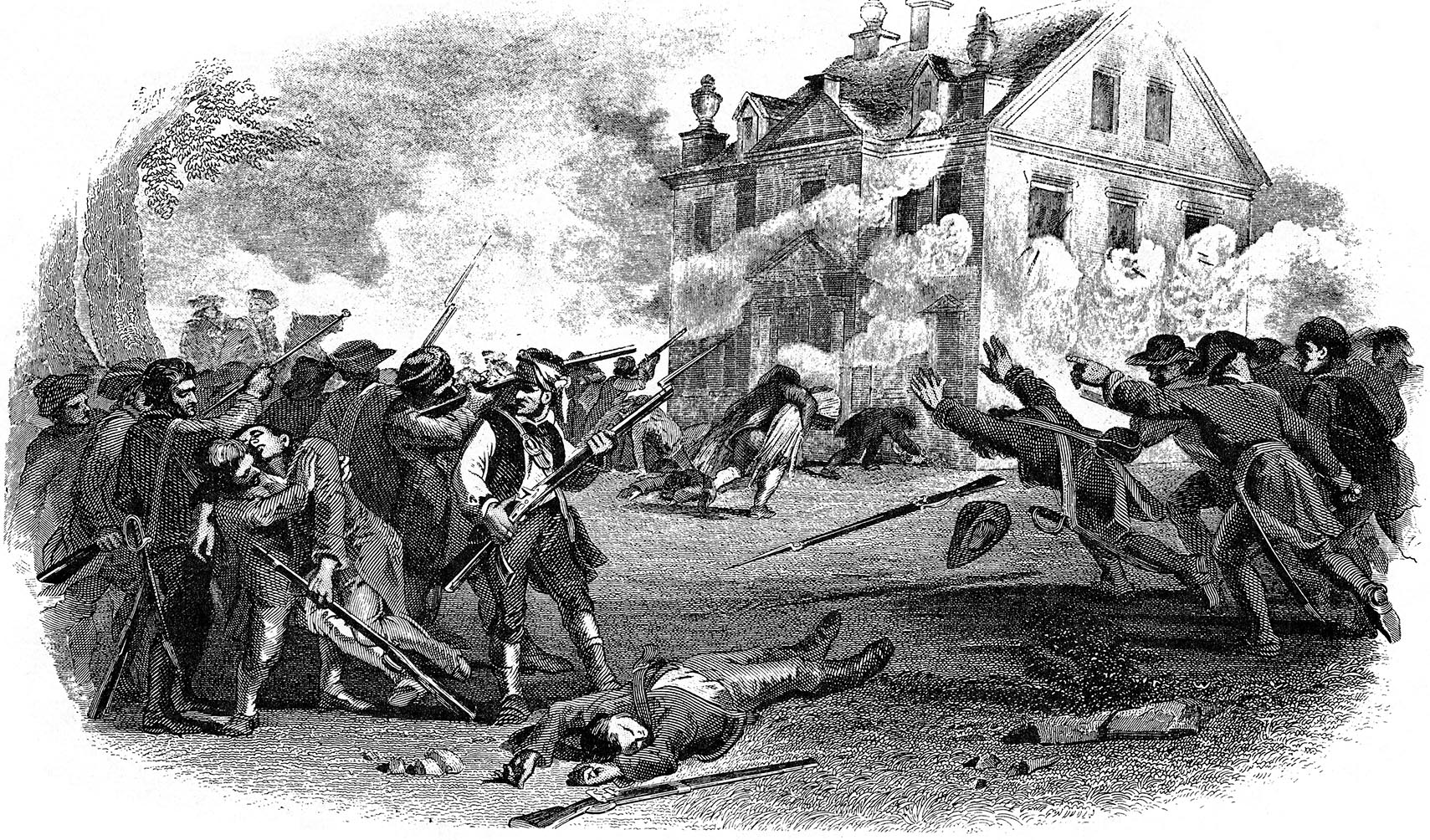

It was nearing 7 am when the first American cannonball pounded into the mansion’s front doors, ripping them from their hinges. More guns quickly joined the action, the cannonade rising in intensity with each roaring salvo. Cannonballs hammered the walls, the mansion shuddering and reverberating under the merciless pounding.

The walls were two feet thick, made of schist, and although the outer façade was soon pitted with craters like the face of the moon, the American cannon did little structural damage. The redcoats inside Cliveden, however, did not escape unscathed. Hurtling iron balls punched through shuttered windows, sending out starbursts of glass shards, stone fragments, and wooden splinters in their wake. Soldiers were bloodied by careening wooden splinters, deafened by cannon blasts, and half-choked by plaster dust.

Captain William Harris of the 40th Foot ordered his men to pile chairs, tables, and any other furniture they could find against the shattered doors as a buffer against the American cannonade and a barrier against the assault that was sure to follow. These orders proved to be a wise precaution.

It was obvious that the cannonade alone was not going to force the British to capitulate; the only other option was a direct assault. Attacking Cliveden by foot would be an act of suicidal courage, but the Americans were determined to succeed. The New Jersey Brigade, composed of Colonel Matthias Ogden’s 1st New Jersey Regiment and Colonel Elias Dayton’s 3rd New Jersey Regiment, was assigned the daunting task.

Proctor’s artillery would provide cover fire in the form of grapeshot blasts, lethal sprays of small iron balls. Every effort was made to train the cannon on Cliveden’s upper floor, where British soldiers could pour a deadly fire down on their attackers. Dayton, a splendid figure in buff and blue, unhesitatingly led the brigade forward on horseback.

The artillery ceased fire when the surging blue mass was almost at the house. British muskets sprouted predictably from shattered windows and began to pump a steady rain of lead at the American soldiers below. Dayton’s horse was shot from under him a scant three yards from the northwest corner of the mansion. Dozens of Continental soldiers also fell, but the rest pushed forward. Some actually reached the front steps and boldly attempted to force their way in through the splintered front door. Those who elbowed their way inside were bayoneted again and again by British defenders, cruelly impaled by 17 inches of cold steel blades.

The 3rd New Jersey was forced to fall back, leaving behind them a bloody trail of dead and wounded. American artillery roared back to life. Because of the mansion’s Georgian symmetry, front and rear windows were perfectly aligned. Some cannonballs sailed right through the house, literally going in one window and out the other. At one point, some courageous American staff officers attempted to sneak up and torch the building, but their efforts also failed.

Meanwhile, the men of the 40th Foot kept firing, their muskets blossoming smoke and flame with clockwork regularity. It was hard work to load a musket with its bayonet attached, but the redcoats were well drilled and professional. Biting off cartridges left a powder residue on the lips and in the throat that produced a raging thirst. Faces were blackened with powder smoke, beaded with sweat, and daubed with the crimson of numerous wounds.

Cliveden’s interior, once the pride of the Chew family, was a total wreck. Elegant furniture was smashed and splintered, piled haphazardly against the doors. Paintings had fallen from walls or hung askew at crazy angles, the figures in the portraits gazing down serenely at the carnage around them. Walls were peppered with holes, wallpaper hung in shreds, and interior columns were gouged and splintered.

The air was smoky and foul, the fetid chambers stirred only by the occasional passage of an American cannonball. The rotten-egg odor of expended gunpowder combined with the smell of powdered wood, plaster, and spilled blood to produce a sickening stench.

Greene’s column finally reached the battlefield about 7 am and immediately drove in the pickets of the 1st Battalion, British Light Infantry, after some stiff fighting. Private Joseph Martin, a young American soldier with Greene’s command, remembered, “The enemy were driven quite through their camp. They left their kettles, in which they were cooking their breakfasts, on the fires, and some of their garments were lying on the ground, which their owners had not had time to put on.”

Natural Obstacles Made Worse by Thick Fog

The linear tactics of the period demanded close contact between units, but Greene’s formations were disordered by the maze of fences, meandering streams, and thick clumps of trees they encountered. Natural obstacles were made worse by the thick fog that stubbornly refused to dissipate. One of Greene’s units, the Virginia Brigade under Colonel William Woodford, was drawn irresistibly to the sounds of the fighting at Cliveden. Soon the great building appeared though the fog like a ghostly apparition.

The Virginians reached the rear of the house, and when the redcoats began firing at them from the second floor they lost no time in unlimbering their guns. Now Cliveden was completely surrounded by Continental forces and enduring another bombardment by no less that eight guns. The roar of cannon and rattle of musketry around Cliveden became so intense that other American regiments also began to take notice.

Wayne’s Pennsylvanians were still groping their way toward the main British force, trading volleys in the thick, gray void. But as the sounds of the Cliveden battle grew ever louder in their rear, the men began to entertain doubts. Had the British managed to get around their line and mount a counterattack?

Some of Wayne’s troops halted and began to countermarch, retracing their steps in Cliveden’s general direction. Wayne already had lost contact with Sullivan’s troops even before the countermarch—now the gap was a yawning chasm.

Worse was soon to follow. General Adam Stephen’s brigade, part of Greene’s latecomers, was lost and disoriented. The situation was not helped by the fact that the general was drinking freely—in fact, he was dead drunk.

As Stephen’s men stumbled forward, they suddenly encountered a body of troops emerging from the fog. Thinking the strangers must be British, Stephen’s brigade fired a volley, which the opposing force immediately returned. Tragically, the unknown troops were part of Wayne’s division, the same men who had been marching toward Cliveden and the sounds of the guns. An untold number of Americans were killed by friendly fire before the confusion was straightened out, and the sudden departure of Wayne’s troops left Sullivan isolated and vulnerable to flank attacks.

British Maj. Gen. James Grant attacked Sullivan’s left with his own 55th Foot and 5th Foot, while other British forces attacked his right. At this crucial moment, Washington’s worst fears became reality—some of the Americans were out of cartridges, or nearly so. Private Martin recalled that his fellow soldiers pleaded loudly for more ammunition, thus unwittingly alerting the British to their plight.

Pressed on all sides, confused and disoriented, the Americans began to fall back. Some Continentals showed signs of panic, but most regiments were calm and even defiant. Thomas Paine, the famous writer of such revolutionary tracts as Common Sense, was on the scene, and he noted later that “the retreat was extraordinary. Nobody hurried themselves.” The British exploited their growing advantage, and soon Cliveden itself was relieved. After three hours of hard fighting, the Americans were in full retreat. In the confusion that closed the battle, the 9th Virginia Regiment was captured en masse.

Cliveden had seen some of the heaviest fighting. Both house and grounds were in shambles. A Hessian officer, no stranger to bloodshed, was appalled by the horrors he beheld at the scene. The estate looked like a slaughterhouse—blood was splattered everywhere. As many as 50 Continental bodies lay sprawled about Cliveden’s once-splendid lawn and front door. The British garrison had suffered remarkably few casualties, especially considering the heavy bombardment and assault they had endured—two were killed and 26 wounded. Later, Musgrave commissioned a special medal to commemorate the event. Each officer and man received the award, the first combat decoration to be given for a specific engagement in the British Army.

Performing Well Under the Circumstances

All in all, the Continental army had performed well under the circumstances, and morale was not damaged when the near-victory turned suddenly into defeat. The Americans sensed that their complicated plan had almost succeeded. “Fortune smiled on us for full three hours,” General Wayne wrote afterward, summing up the battle. “The enemy were broke, dispersed and flying in all quarters. We were in possession of their whole encampment, together with their artillery park…. A wind-mill attack was made upon a house…. Our troops … thinking it something formidable, fell back to assist—the enemy believing it to be a retreat, followed—confusion ensued, and we ran away from the arms of victory open to receive us.” Still, the idea of relatively inexperienced American soldiers standing toe to toe with the cream of the British Army and coolly trading volleys was itself a kind of victory, whatever the ultimate outcome of the battle.

Better days were coming, as surely as the leaves were beginning to turn brown in the Pennsylvania hills. It was a belief that would help the Continental forces endure the brutal winter soon to come at Valley Forge, where they would face—and conquer—an even sterner challenge to their revolutionary spirit.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments