By Henrik Lunde

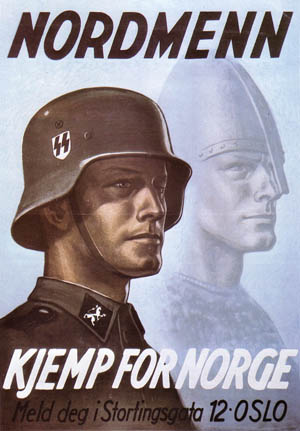

On the surface it may seem odd that men of conquered nations would eagerly sign up to fight for their masters, but that is exactly what happened in Scandinavia in the 1940s. Although a small number of Scandinavians served in the German armed forces before 1940, it was not until after the invasion of Denmark and Norway in April 1940, two years before the fighting in the Demyansk Pocket, that Waffen-SS recruiting offices were opened in Copenhagen and Oslo.

This was a result of Himmler’s order to establish a Waffen-SS unit composed of volunteers from the two countries and the Netherlands: SS Wiking—which was to be filled by what was referred to as “Germanic recruits.”

The plan called for one regiment of Germans, one regiment of Dutch (Westland), one regiment of Scandinavians (Nordland), and a Finnish battalion. However, recruitment was not a roaring success as only 3,000 Scandinavians, including Finns, signed up.

The Germans tried again in 1941, hoping that the war between the Soviet Union and Finland would spur the recruitment effort. However, now the Danes and Norwegians were organized in national legions—the Norwegian Legion (DNL) and Frikorps Danmark.

The German attack on the Soviet Union, and Finland’s participation in that attack, made potential volunteers of right-wing nationalist groups who were not National Socialists and had, up to then, been skeptical. Anti-communism became the dominant recruitment theme. Potential recruits were encouraged to enlist in a war described as a crusade to protect Europe against Bolshevism. Furthermore, physical requirements for volunteers diminished in subsequent years as the war on the Eastern Front resulted in heavy casualties.

Many nationalities served in Germany’s elite Waffen-SS during World War II, including Scandinavians, and particularly Danes. The recruitment of foreigners was designed to overcome the strict limits imposed on the growth of the Waffen-SS by the Wehrmacht, which had established a virtual monopoly on recruiting in Germany. This forced the Waffen-SS to look outside Germany for manpower. (Read more about the other forces at work during the Second World War inside the pages of WWII History magazine.)

Prior to 1940 there were only a few volunteers, but after the invasions of Norway and Denmark in the spring of 1940, their numbers increased considerably. The Scandinavians in German service were primarily Norwegians and Danes although there was also a smattering of Swedes and one battalion of Finns.

There is general agreement in the sources that over 20,000 Norwegians and Danes joined the Waffen-SS during the war. These break down to around 13,000 Danes, 7,000 Norwegians, 1,500 Finns, and a few hundred Swedes. Of approximately 13,000 Danish citizens who volunteered for German armed service during World War II, some 7,000 were accepted.

The vast majority—around 12,000—volunteered for the Waffen-SS, and that organization admitted around 6,000. In looking at the number of Danes, it should be remembered that the size of the prewar Danish Army was only 6,600. The Finns spent most of their time in SS Division Wiking but were withdrawn to Finland in 1943. The Swedes served for the most part in Army Group North’s sector.

At any one time, about 3,000 Scandinavians served at the front and acquitted themselves well. The SS Division Nordland, for example, won the fifth highest number of Knight’s Crosses of all the Waffen-SS divisions. However, the Scandinavian volunteers never reached the large numbers envisioned by SS chief Heinrich Himmler.

The greatest number of Danes served in three different formations: Frikorps Danmark (Danish Legion), SS Division Wiking, and, after the disbandment of the so-called legions in 1943, the SS Division Nordland. Approximately 1,500 Danish volunteers came from the German minority in southern Jutland, and they served mainly in SS Division Totenkopf and to some extent in that division’s infamous 1st SS Brigade.

The first group of Danish volunteers was deployed in the summer of 1941 when SS Division Wiking participated in the attack on the Soviet Union; only a few hundred Danes served in this division at any one time. The majority of them were transferred to SS Division Nordland after two years of serving in Wiking; most Danish volunteers were still undergoing training in Frikorps Danmark when Wiking fought in the Ukraine.

Frikorps Danmark was created on June 25, 1941, within a few days following the German invasion of the Soviet Union. About 500 volunteers signed up in the first couple of weeks, but the unit grew to about 1,000-1,200 in the following months. The creation of the Frikorps was accepted by the Danish government and the Danish Army, and officers who wished to serve in the Frikorps were given a leave to do so from the Danish Army. Both the government and the army sent representatives to the departure ceremony of the Frikorps as the troops left Denmark and marched off to war.

Many of the Scandinavian volunteers were veterans from the Finnish Winter War against the Soviets or had seen service in the Norwegian and Danish Armies; similar legions were recruited in the Netherlands and Flanders and were organized in cooperation with SS headquarters in Berlin and the various national Nazi parties.

This arrangement with the various Nazi parties in occupied Europe served to underline the national character of the legions and gave them some autonomy by appointing officers from within their ranks rather than Germans. It was also designed to foster the anti-communist theme and counter the belief in the occupied countries that the volunteers were composed only of people who were pro-German. However, recruits continued to come mainly from Nazi circles in the occupied countries.

The legions never reached full regimental strength in the early years. Their training and equipment were not the best, they had no armor, and there was a shortage of heavy weapons.

In early 1942, the Norwegian Legion (Den Norske Legion) was sent to the siege lines around Oranienburg and Leningrad, where they spent a frustrating 18 months slugging it out with the Russians in almost World War I-like conditions as their strength dwindled and reinforcements dried up. The Danes faced equally dismal or worse conditions when they were sent into the Demyansk Salient to reinforce the SS Totenkopf Division in the summer of 1942.

Some of the general histories of World War II on the Eastern Front make only brief reference to the epic struggle that took place over the Demyansk Salient during the spring and summer of 1942. Consequently, the reader will find it useful to learn what this struggle was all about and how it factored into the strategic plans of both the Soviets and Germans.

At times Demyansk is described as a salient extending eastward from the main German defensive lines, and at other times, when totally encircled, as a pocket. Depending on the situation, it will be referred to here as one or the other.

While the role of the Danish Waffen-SS was, in many respects, minor in the overall scope of the conflict on the Eastern Front, it resulted in the worst single bloodletting suffered by Danish volunteers in Word War II. Since little has been written in English about the Scandinavian volunteers in the Waffen-SS, here is a summary that attempts to fill that void.

The Strategic Setting

The primary purpose of the Soviet winter offensive that began in December 1941 was to eliminate the German threat to Moscow posed by Generalfeldmarschall Fedor von Bock’s Army Group Center. The Soviet success in the battle for Moscow delivered a serious blow to the mantle of German invincibility and caused Stalin and the Soviet High Command (Stavka) to become overly optimistic and ambitious. The result was that Stavka extended the offensive the whole length of the Eastern Front—from northern Finland in the north to the Black Sea in the south. The hoped-for results were the destruction of Army Group Center, the relief of Leningrad, and driving the Germans out of the Crimea and the Donets Basin.

In retrospect it is obvious that Soviet objectives were too ambitious. While the battle for Moscow had been a serious setback for the Germans, they were by no means as shattered and exhausted as the Soviets seem to have assumed. By attacking everywhere, the Soviets diluted their efforts. Also, by extending the conflict through the spring thaw, they created a condition favoring the defenders.

This allowed the Germans to mount an extraordinary defense in a climate characterized by bitter cold and deep snow—conditions for which the German soldiers were neither prepared nor equipped. The Soviets also suffered; a look at the casualty figures tells the story. The Soviets suffered a staggering 620,000 killed between January and March 1942 while, at the same time, the German death toll was roughly 136,000.

This ratio remains essentially the same when total casualties (killed, wounded, captured, and missing) are considered. Furthermore, the Soviet mobility, operational effectiveness, and supply apparatus were not yet capable of supporting these massive offensives over extended distances. In his memoirs Soviet Marshal Georgi Zhukov notes angrily, “If you consider our losses and what results were achieved, it will be clear that it was a Pyrrhic victory.”

The Soviet strategy of wearing the Germans down did not work, and, in return for huge losses, the Soviets gained little territory and were faced with having to rebuild their weakened forces before an expected German summer offensive, which the Soviets assumed would have Moscow as its main objective. When the Germans struck with the main effort in the south, they found the Soviet military in a precarious posture similar to that of the previous year. This was to a large extent the result of the widely dispersed Soviet efforts in the winter and spring.

Army Group North’s Southern Sector and Demyansk

On both sides of the boundary between Army Groups Center and North, the Russians had managed to drive deep into the German front. At one point it appeared that they would be able to encircle the Ninth Army and the Third Panzer Army. This possible calamity was averted, however, and Feldmarschall Günther von Kluge, commanding Army Group Center after Bock was relieved in early 1942, was even able to push the Soviets back in some areas.

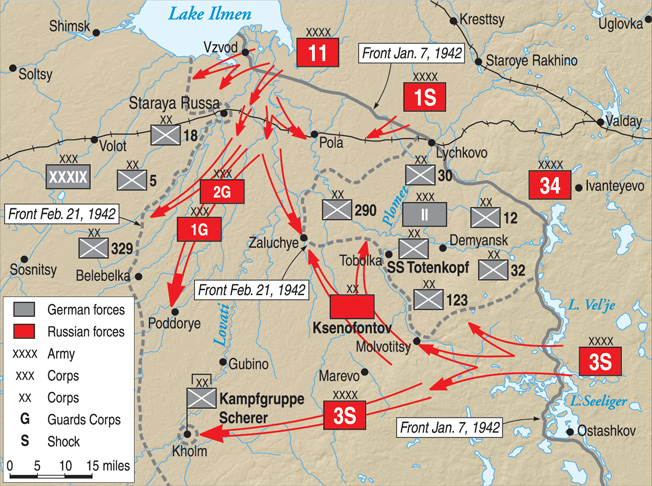

The Russians did control a huge bulge extending into German lines around Toropets, in the northern part of Army Group Center’s sector. The northern part of the bulge actually extended into Army Group North’s sector as well, from Kholm in the southwest to Demyansk, a city located approximately 100 miles south of Leningrad, in the northeast.

Army Group North, commanded by Feldmarschall Wilhelm Ritter von Leeb, consisted of two armies, the Eighteenth under General Georg von Küchler and the Sixteenth under General Ernst Busch. The Eighteenth Army was in the north, around Leningrad, and its front extended south as far as the northern shore of Lake Ilmen. Busch’s Sixteenth held the southern part of the army group’s sector from Lake Ilmen to a point near the town of Kholm.

The Soviets hurled nine armies against Army Group North in their winter offensive, trying to break the siege of Leningrad and push the German front away from Moscow by levering it away from the strategic Valday Hills. It was even hoped that Küchler’s and Busch’s armies could be encircled and destroyed.

Sixteenth Army tied into the LIX Corps of Army Group Center in the vicinity of Kholm. Its front was long because it incorporated a large salient extending toward the Valday Hills and ran northeastward from Kholm, then east past the city of Demyansk, and then back in a west-northwest direction to the city of Staraya Russa, south of Lake Ilmen.

During the German drive to the east in 1941, II Corps of the Sixteenth Army, under Lt. Gen. Walter Graf Brockdorff-Ahlenfeldt, had captured Demyansk, reached the strategically important Valday Hills, and cut the railway line between Moscow and Leningrad. But here the corps became stuck. They held out in these forward positions throughout the early winter, although the Soviets gave this salient, sticking out like a finger eastward for over 60 miles from the main German line of resistance, special attention.

The elongated salient was important to both the Germans and the Soviets, and for much the same reasons. Hitler and the OKH (Oberkommando des Heeres) viewed the salient as an ideal jumping-off point for a possible resumed offensive against Moscow. Stavka was well aware of this, and the salient took on added importance in its calculations as the Soviets misread the enemy intentions in the expected German offensive: Stavka referred to the Demyansk Salient as a dagger pointed at Moscow.

The salient also posed a serious flank threat against the gigantic bulge the Soviets had driven into Army Group Center in the Toropets-Velikiye Luki area. If the Germans could mount a southward offensive from the Demyansk Salient in conjunction with a northward offensive by Army Group Center, a large pocket of Soviet forces would be encircled.

While the Germans were aware of the opportunities presented by the Toropets bulge and the overextension of their enemy, they were unable to do anything about it. The German armies were bled white in the offensive of 1941 and the subsequent Soviet winter offensive. The bloodletting could not be offset by replacements that were slow in arriving, and there were virtually no reserves. The observations of General Gotthard Heinrici, commander of the Ninth Army, show how drastic the personnel situation was. He reported that his battalions were down to about 70 men in strength, with an average of seven light and heavy machine guns each.

Because of its importance to both sides, the Demyansk Salient became one of the most hotly contested areas of the Eastern Front, and both sides fought over it bitterly. Brockdorff-Ahlenfeldt, commanding II Corps assigned to the Sixteenth Army, was given the mission of defending the Demyansk Salient. He was a 54-year-old aristocrat who had entered the German Army in 1907 and had distinguished himself as a corps commander in the French Campaign of 1940.

When the Soviet offensive began in Army Group North’s sector in January 1942, Brockdorff-Ahlenfeldt’s II Corps had three divisions: the 12th Infantry Division from Mecklenburg, the 32nd Infantry Division from Pomerania and Prussia, and the 123rd Infantry Division from Brandenburg. These divisions from northern Germany had taken part in the German invasion of Russia in 1941, and, as a result of the eastward drive and subsequent fighting, they were, as other German units, well below their authorized strength.

In addition, the men were fighting in summer uniforms with the temperature at times falling to below minus 40 degrees Fahrenheit, virtually immobilizing both men and machinery. While frontline troops were given additional clothing by rear area personnel, it was of little help since those personnel also had only summer uniforms.

The Soviet Northwest Front was commanded by Lt. Gen. Pavel Kurochkin. Its mission was to encircle the northern flank of the Sixteenth Army—a goal to be accomplished by two large drives by troops from both the Northwest Front and the Kalinin Front.

Three armies made up the northern drive. The 11th Army, under Lt. Gen. V.I. Morosov, attacked in the Lake Ilmen area; the 34th Army, under Maj. Gen. Nikolai Bersarin, concentrated on the Valday Hills area; and the 1st Shock Army.

The southern drive was made up of the 53rd Army, under Maj. Gen. Aleksandr Ksenofontov, the 22nd Army under Lt. Gen. V.A. Yashkevich, and the 3rd Shock Army. These units were to make the breakthrough to Kholm and constituted the southern force that was to encircle Demyansk. These attacks were supported by large-scale partisan activities in the German rear, particularly in the Staraya Russa area.

The attack in the north was initiated on January 7, 1942, by the 11th Soviet Army, elements of the 1st Shock Army, and two Guards Rifle Corps (1st and 2nd) released from Stavka’s strategic reserve. Two days later the 3rd Shock Army from the Kalinin Front, along with the 53rd and 22nd Armies, attacked westward against Kholm and Lake Seeliger on the boundary between Army Group Center and Army Group North. A successful breakthrough in this area would leave the Soviets in a position to drive into the rear areas of both German army groups.

The German X Corps, commanded by General Christian Hansen, on II Corps’ left flank, was also driven back by relentless Soviet pressure. The X Corps, like II Corps, had three divisions, and these all ended up in the Demyansk Salient. These were the 30th Infantry Division from Schleswig-Holstein under General Kurt von Tippelskirch, the 290th Infantry Division from Hanover and Schleswig-Holstein under General Theodor Freiherr von Wrede, and the 3rd SS Totenkopf Division under the ruthless SS Obergrupenführer (equivalent to General der Infanterie) Theodor Eicke, who had once been in charge of all concentration camp guards.

The Soviets infiltrated between the strongpoints of the 290th Infantry Division and the 30th Infantry Division on the night of 7/8 January. Dawn on the 8th found strong Soviet infantry and tank formations already behind the 290th Infantry Division, and Soviet transport gliders also brought in troops and tanks onto frozen Lake Ilmen.

These infantry and tank forces crossed the ice and reached the junction of the Lovati, Redya, and Polisti Rivers, 25 miles to the rear of the 290th Division. A total of 19 Soviet infantry divisions, nine brigades, and several independent ski and tank battalions were meanwhile attacking the fronts of X and II Corps.

The main effort of the 11th Soviet Army was against the front of the 290th Division near Tutilovo. To the north, the Germans mounted a desperate defense but were overrun in vicious fighting. The right flank of the division held for another day, and then it collapsed. Withdrawing to the west to avoid encirclement, the 290th ran into fierce battles around various towns and strongpoints on its way.

The 1st and 2nd Soviet Guards Corps drove southward behind the 290th Infantry Division. The 2nd Guards attacked Parfino while the 1st Guards attacked toward Salueje; Soviet ski troops were approaching Staraya Russa. The Germans scraped together a motley array of rear area troops to try and hold them back while the 51st Infantry Regiment of the 18th Motorized Infantry Division was brought in from Simsk in an effort to stabilize the situation.

But the 290th Division became encircled and could only be supplied by air after January 25. The division repulsed a total of 146 enemy attacks between January 8 and February 13, the day it, with superhuman effort, finally was able to break out of the encirclement.

The II Corps front was also collapsing. The Soviets placed the main effort of their offensive on the boundary between Army Groups North and Center. Here they attacked on January 9 after a two-hour artillery preparation. Six rifle divisions along with several tank and ski battalions attacked on either side of Ostaskhov on Lake Seeliger.

The 53rd Army and elements of the 22nd Army and 3rd Shock Army smashed into and virtually annihilated two regiments of the 123rd Infantry Division, creating a large gap through which Soviet troops poured.

The 34th Soviet Army, reinforced by two Soviet airborne brigades, was meanwhile pressing against the salient from the east. By January 12, General Brockdorff-Ahlenfeldt had received permission to withdraw the easternmost part of his front.

When Brockdorff-Ahlenfeldt was appointed commander of all German forces in the pocket, X Corps commander Hansen, minus his divisions, was transferred to Staraya Russa to command German forces in this area.

The salient held by the Germans around Demyansk looked like a “misplaced thumb” on the map, in the words of U.S. Army historian Earl F. Ziemke. The pocket was threatened from the east by the Soviet 34th Army while the base of the salient was threatened by the First Shock Army from the north and the Third Shock Army and the 53rd Army from the south.

Operationally, OKH thought, the pocket performed two services: it kept Russian troops tied down, and it might be used as one arm of an encircling operation against the Toropets bulge, but the question was whether anything of the sort was intended or could be executed. If not, Feldmarschall Ritter von Leeb maintained, the pocket was valueless.

Leeb was greatly concerned about the situation on his front and called Führer Headquarters on January 12, proposing that his armies be withdrawn behind the Lovati River. Not surprisingly, Hitler immediately turned down the proposal. Leeb thereupon flew to East Prussia to personally argue his case; Hitler again refused. Leeb then requested to be relieved of his command, and Hitler agreed. General Georg Karl Friedrich Wilhelm von Küchler was given command of the army group; his place as commander of the Eighteenth Army was taken by General Georg Lindemann.

By mid-January the southern front of the Sixteenth Army had ceased to exist. The battered 123rd Infantry Division was reduced to defending strongpoints in the vicinity of Molvotisyn, and the division’s 415th and 416th Infantry Regiments were separated from the rest of the front. In 10 days of vicious fighting these two regiments made their way through enemy lines and back to their own front. When they arrived, their combined strength was a mere 900 men.

The 32nd Infantry Division (Maj. Gen. Wilhelm Bohnstedt) and the 123rd Infantry Division (Maj. Gen. Erwin Rauch) from Brandenburg managed eventually to construct a temporary southern front—a front 118 miles wide. However, the combined strength of the two divisions had fallen drastically to about 12,000 men.

The Russians could not fully exploit their initial successes because isolated German units formed strongpoints in villages that were bypassed by the initial Soviet assaults, and follow-on Russian units had to divert forces to try to overcome them. Some of the strongpoints fell, while others held out for weeks. The desperate resistance by these strongpoints helped to stabilize the front.

However, the situation became critical as II Corps was in danger of being encircled. Fresh Soviet divisions poured into the 56-mile-wide gap in the south, forcing Bohn-

stedt’s and Rauch’s divisions to fall back. A message from II Corps to the Sixteenth Army stated that they would withdraw behind the Lovati River as soon as an opportunity presented itself. The answer, from OKH, was short and curt: Demyansk was to be defended to the last man.

The II Corps withdrew all battalions that were under the control of SS Obergruppenführer Eicke and hastily transported them to the Salueje area to block the western front where these combat groups occupied a baseline in case the Soviets cut the salient near its base. They managed to do this just in time since the troops of the 34th Soviet Army and the 1st Guards Corps met on February 8 near Rambushevo on the Lovati River. The Demyansk Salient had become the Demyansk Pocket, containing approximately 100,000 German troops ready to be slaughtered.

By January 23 the city of Kholm, about 56 miles southwest of Demyansk, was encircled by the 3rd Shock Army. The Germans’ 81st Silesian Infantry Division had just arrived in Army Group Center’s sector and was immediately sent north toward Kholm. The troops had no winter clothing or winter equipment, but they repulsed the attack of four Soviet divisions in minus 46-degree cold. Although this action disrupted the attack of the 4th Shock Army, the situation remained critical.

Kholm served to break the force of the Soviet flood. If the Germans lost this city, the Soviets would be able to drive into the rear of both Army Group Center and the Sixteenth Army. Maj. Gen. Theodor Scherer, commander of the lightly armed 281st Security Division, was appointed commandant of Fortress Kholm. He scraped together whatever troops he could lay his hands on, which eventually numbered about 5,000.

Contact between the troops in Kholm and their neighbors was lost at the end of January. Kholm, like Demyansk, had become a pocket that could only be supplied by air.

The six divisions available to Brockdorff-Ahlenfeldt in the Demyansk Pocket were disposed as follows: The 12th Mecklenburg and the 32nd Pomeranian Infantry Divisions were located east and south of Demyansk, while the remnants of the 123rd Division were fighting in the southwest part of the pocket. The two infantry divisions from northern Germany—30th and 290th—defended north of Demyansk, while part of the SS Totenkopf Division [under SS Standartenführer (colonel) Max Simon] was in the northeast. The combat groups under Eicke held positions in the west. The size of the pocket was 1.865 square miles, the length of the front that had to be defended was about 186 miles, and the distance across the pocket was some 30-45 miles.

In his first order of the day after the pocket was formed, Brockdorff-Ahlenfeldt defiantly stated, “There are 96,000 of us. The German soldier is superior to the Russian; this has been proven. So, let the difficult times come; we are ready.”

Unlike the earlier pocket at Sukhinichi, Hitler refused to abandon either Kholm or Demyansk. After being assured by the Luftwaffe that the reinforced 1st Air Fleet could deliver the required 240-265 tons of daily supplies to the two pockets, Hitler ordered that the pockets be defended until relieved.

Successful Resupply

On February 18, the OKH ordered the redeployment of the air transport command out of the Smolensk area and into Luftflotte 1’s area of operation—an operation that used almost all of the Luftwaffe’s transport capability, as well as elements of its bomber force. Since the Demyansk Pocket contained two usable airfields at Demyansk and Peski, the supply effort involved both airdrop and air-landing (glider) operations.

The weather improved in the middle of February, but there was still considerable snow on the ground. Supply operations were generally successful, due primarily to the weakness of the Soviet air forces in the area.

The Luftwaffe flew 33,086 sorties until the Demyansk Pocket was evacuated in March 1943. The two pockets—Demyansk and Kholm—received 59,000 tons of supplies by both ground and air. A total of 31,000 replacement troops were brought in and 36,000 wounded evacuated. But the cost to the Luftwaffe was significant. It not only lost 265 aircraft, but the loss of 387 experienced airmen was even more serious. For their part, the Soviet Air Force reportedly lost 408 aircraft, including 243 fighters.

Author Werner Haupt incorrectly writes that this was the first air bridge in history, while Paul Carell notes that in 14,500 missions—apparently when the pocket was encircled—the Ju-52 transport planes of the Luftwaffe established the first airlift in history; other writers have made similar incorrect statements. In the 1940 German invasion of Norway, an air bridge was established from Germany and Denmark to Norway. Five hundred eighty-two transport aircraft flew 13,018 sorties and brought in 29,280 troops and 2,376 tons of supplies. In addition, smaller air bridge operations took place from Oslo to the other isolated landing sites on the long Norwegian coast.

But the success of the Luftwaffe in bringing in supplies and replacements in Russia, as well as evacuating casualties, convinced Hitler and Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring that they could conduct effective airlift operations in other places on the Eastern Front. Later, when the Sixth German Army was encircled at Stalingrad, Göring proposed that it be supplied by air. He and Hitler theorized that the outcome would be similar to Demyansk and Kholm since the Sixth Army was in fighting condition.

They went on to posit that with the Luftwaffe supplying the army, the Soviets would expand their strength to contain the encirclement and this would allow the time needed by the German forces to regroup and counterattack.

However, the conditions under which the two operations (Demyansk and Stalingrad) had to be conducted differed greatly. While a single corps with about six understrength divisions was encircled in Demyansk, a heavily reinforced army was trapped in Stalingrad. Whereas the Demyansk and Kholm Pockets together needed around 265 tons of supplies by air each day, the Sixth Army required an estimated daily supply of 800 tons, which had to be delivered over much greater distances. The Stalingrad airlift also faced much better organized Soviet air forces.

By the winter of 1942-1943, then, the German air transport forces had already suffered heavy losses, and the distances to good airfields with maintenance and repair facilities were much greater. The Luftwaffe simply lacked the resources needed to supply Stalingrad.

The Last Stand

Ernst Busch’s Sixteenth Army began planning to break into the Demyansk Pocket from the west after Hitler’s refusal to allow a withdrawal behind the Lovati River. A group was formed under the command of General Walther Kurt von Seydlitz-Kurzback, the commander of the 12th Infantry Division. (This was the same Seydlitz who was captured at Stalingrad and became a key figure in a Soviet-sponsored anti-Nazi faction.)

Seydlitz’s group was substantial and included two infantry divisions, two light infantry divisions, a motorized infantry division, a security regiment, a panzer regiment, a Luftwaffe field regiment, and various construction units, assault gun batteries, and air defense battalions. The plan called for a simultaneous westward attack by forces in the pocket; it was hoped that the two attacks would link up on the Lovati River.

Group Seydlitz-Kurzback and the attackers from within the pocket reached the Lovati River near the destroyed village of Rambushevo on April 21, 1942. The men of the SS Totenkopf Division and the spearhead of Group Seydlitz-Kurzback were still separated by a 1,000-foot-wide swollen and turbulent river.

As soon as bridges were built, a corridor existed again between the main German front of Sixteenth Army from Staraya Russa to Kholm and the divisions in the Demyansk area. The Demyansk Pocket had again become the Demyansk Salient, as the corridor barred to the Soviets the way across the land bridge between Lakes Ilmen and Seelinger.

The Rambuschevo Corridor was worryingly narrow in the beginning, though, and the Germans set out to widen it. There was a serious danger that the Soviets could cut the salient off at its base. That would have annulled the fighting for the corridor, which had cost the Germans 3,335 killed and over 10,000 wounded.

The Russians, increasingly anxious to wipe out the Demyansk Salient, made a number of desperate assaults on the thin Rambuschevo Corridor; Obergruppenfüher Eicke had the primary responsibility for keeping the corridor open. The Germans were fighting desperately in subzero temperatures and in three feet of snow to prevent the Russians from severing the connection to Staraya Russa and the rest of Army Group North.

The influential Eicke demanded reinforcements to keep his forces alive, but there were none available from either the Sixteenth Army or Army Group North. OKH, in looking around for available forces, decided to send Frikorps Danmark into the salient.

Frikorps Danmark at Demyansk

Frikorps Danmark was located in Posen-Treskau where its Danish commander, the charismatic Danish/Russian aristocrat Christian von Schalburg, was training his organization, which had been plagued by internal dissent, and had transformed it into a solid and well-trained reinforced battalion after integrating 10 German officer instructors with combat experience into key posts to stiffen the unit. But, as with its sister formation, the DNL, the majority of the Frikorps commanders were Scandinavian, not German.

Frikorps Danmark had three infantry companies and one heavy weapons company. The latter consisted of two platoons of 75mm infantry guns, one platoon of 50mm antitank guns, and a combat engineer platoon, all at full strength. Most of the troops lacked combat experience, but the majority of the officers and noncommissioned officers had some, either from the Finnish Winter War, from service in the Wiking Division, or against the Germans in 1940. Although the unit was at full strength, it had only seven heavy-caliber weapons.

Frikorps Danmark was declared combat ready in May 1942. In the early days the volunteer legions were considered second rate compared to German units and were judged unsuited for anything but static warfare and antipartisan fighting—a fact that goes a long way to explain their lack of heavy-caliber weapons.

This perception was about to change. After receiving its deployment order, the Frikorps was flown into the Demyansk Salient from Heilingenbeil near Köningsberg on May 8, 1942. Historian Claus Bundgård Christensen and others have written that 1,200 Danes were flown into the pocket, but other sources mention a lower number. Christensen may have meant the total number in Frikorps Danmark or included a number of Danes already serving in the 3rd SS Totenkopf Division.

The Danes were attached to Eicke’s SS Totenkopf Division and immediately thrown into the fighting where they took up positions along the Robja River with the mission of keeping the Russians from expanding a bridgehead they had in the area of Ssutoki. The Soviets were on the far bank but had managed to get some troops over to the German-occupied side where they formed a small bridgehead. If they could expand the bridgehead and ferry across some tanks, the Reds would be in a position to launch a full-scale attack that would spell trouble for the hard-pressed defenders of the Rambushevo Corridor.

The Danish commander Schalburg knew that the Soviet bridgehead had to be destroyed. He ordered Johannes Just Nielsen, a veteran of the Winter War and considered one of the best officers in the Frikorps, to carry out an attack on the small bridgehead on the night of May 27/28. Nielsen divided his force into two groups that approached the Soviets from different directions. The attackers managed to get close to the Russians in the darkness without being detected, and Nielsen threw a grenade into the enemy positions as a signal to start the attack.

The Danes rushed the Russian trenches and, although the Reds had a considerable superiority in numbers, the shock of the sudden attack threw them into a panic. Some were killed while the survivors jumped into the river and swam for safety.

While the operation was a complete success, the Russians on the far bank opened up with mortars and artillery. One barrage killed Nielsen, who fell into the river and disappeared. Instead of occupying and remaining in the Russian positions, the Danes made the mistake of withdrawing to their own lines.

Nielsen’s death at Ssutoki was only the first blow to the Frikorps leadership. A few days after Nielsen’s death, the Soviets attacked across the river and reestablished their old bridgehead. The earlier withdrawal now forced the Danes to make another, more costly, attack on June 2, 1942, to try to eliminate the Russian bridgehead. The element of surprise did not work a second time as the Soviets knew the Danes were coming; they blanketed the area with artillery and mortar fire while the Frikorps was still in its assembly areas.

Schalburg went forward to encourage his men and get the attack going, but he was badly wounded when his leg was shattered as he stepped on a mine. His men tried to bring him back, but another Soviet barrage instantly killed him and the two men trying to carry him to safety.

Despite the heavy enemy fire, Alfred Jonstrup, another veteran from the Winter War, managed to recover his commander’s body. The Soviet indirect fire and the loss of the Frikorps commander brought the Danish attack to a standstill despite merciless fighting that resulted in 21 Danes killed and another 58 wounded. The Soviets held their bridgehead.

Schalburg’s body was brought back to Denmark, where he was given a hero’s funeral with full military honors. He became a martyr for the Danish Nazis, and his example encouraged a fresh wave of volunteers for the Frikorps, which needed new reinforcements badly as a result of the continuous fighting at Demyansk.

A friend of Schalburg from Finnish Winter War days, SS Obersturmbannführer (lieutenant colonel) Knud Börge Martinsen took temporary command of Frikorps Danmark and stabilized the situation over the next few days while the Danes waited for a new commander to be appointed.

The new commander, who was appointed by the Germans within a week, was an aristocrat named Hans Albert von Lettow-Vorbeck, who had served in SS-Division Wiking and had been on his way to take command of SS-Legion Flanders when he was diverted to Demyansk.

In the meantime, parts of the SS Totenkopf Division were preparing to launch an operation code named Danebrog to secure the area up to the Pola River and establish a defensible line. The Frikorps had an important role in this operation: the capture of the town of Bolschoje Dubowizy.

Von Lettow-Vorbeck arrived on June 10 and was briefed on the operation scheduled for the next morning. The Danes made a frontal assault on the town at dawn, supported by German artillery, but had to struggle through flooded meadows and swamps before reaching their objective. The Danes entered Dubowizy in the face of bitter enemy resistance and started clearing the town house by house, but their attack was interrupted by a strong Russian counterattack. Two Frikorps company commanders, Boyd Hansen and Alfred Nielsen, were killed in the battle.

By 11 am on June 11, the Russians were on the verge of surrounding the 1st Company, commanded by Per Sörensen, a former officer in the prewar Danish Army and one of the original cadres in Frikorps Danmark. Sörensen eventually rose to head the Danish Waffen-SS before he and many other Danes and Norwegians died in the ruins of Berlin in 1945.

Lettow-Vorbeck decided to move to the front and personally order Sörensen to withdraw before the unit was encircled, but he was killed in a burst of Soviet machine-gun fire. Losing its second commander in a little more than a week had a serious impact on the Frikorps, and, not surprisingly, the Danish attack faltered and collapsed. The Soviets remained in control of Dubowizy. The Danes had 25 of their men killed in the fight for the town in addition to over 100 killed and wounded in the fighting at Ssutoki and the Pola River.

Obersturmbannführer Martinsen again took command of the Frikorps. This time the Germans did not appoint a new commander from the outside but confirmed Martinsen as the commander for the rest of the Frikorps’ existence. Martinsen survived the war but was tried and executed in Denmark for having murdered a fellow Danish SS officer whom he accused of having an affair with his wife.

In early July 1942, the depleted Danes defended a long front between Biakowo and Vassilievschtshina as the Soviets launched repeated attacks against their lines with the objective of cutting the Rambushevo Corridor, which was the only overland connection existing between Demyansk and the main German lines.

July 16, 1942, started out as a quiet day. The Danish soldiers at the front were waiting for a hot meal to be brought forward from the field kitchens behind the lines, but before the food could be delivered or consumed the Danes were subjected to an exceptionally heavy Russian artillery barrage that lasted for over an hour.

In typical fashion, masses of Soviet infantry then rushed toward the Danish defensive positions as soon as the shelling stopped. The Danes, stunned by the heavy barrage, fought back, but they quickly lost contact with the German unit on their right flank and were in imminent danger of being overrun.

Every man in the rear area—cooks, clerks, engineers, and communicators—was sent forward to try to stop the Soviet attack; Luftwaffe Ju-87 Stuka dive bombers were also called in to provide support. Sörensen’s 1st Company was again in the thick of things but was soon decimated and down to only 40 men from its earlier complement of 200. Sörensen called Martinsen and told him that his men would probably not be able to withstand another Soviet assault but that they would not abandon their trenches no matter what happened.

The fighting continued throughout the night. An entire Soviet infantry battalion supported by tanks drove directly into the remaining positions of the 1st Company. The Russians poured into the Danish trenches, resulting in several hours of hand-to-hand fighting as the combatants tried to kill each other with knives, grenades, and entrenching tools. The Russians finally gave up trying to overrun the Danes and withdrew after midnight. They had sustained heavy losses and simply did not have the power to capture the Danish defensive line. The Danes, too, were badly battered.

However, the battle was not yet over as the Russians brought in fresh reinforcements and the Germans also provided reinforcements in the morning in the form of two Jäger battalions—the 28th Jäger Battalion from Silesia and a battalion from the 38th Jäger Regiment. These two units attacked along the road in an attempt to link up with their comrades near Vassilievschtshina. The Russians repulsed the attack and threw the Germans back with heavy losses.

The Soviets attacked again the following morning with waves of fresh infantry supported by numerous T-34 tanks and fighter-bombers. As with the Norwegian Legion, the Danes had no armor or assault guns of their own and had to rely on the few antitank weapons and infantry guns in their heavy weapons company. For the most part they were rather helpless against the T-34s and could only crouch in their trenches as casualties mounted.

Incredibly, despite their losses, the Danes and the German Jägers managed to repel the Russians and stabilize the front line over the next few days. By July 21 the crisis was over. Stavka now appears to have concluded that the main German summer offensive was in the south and not against Moscow as in 1941 and began to withdraw forces from the northern front already in June after reportedly suffering 89,000 killed.

It is not surprising that the Frikorps casualties were heavy. Over 300 Danes were dead by early August, and only about 150 of the original force that was thrown into the fighting at Demyansk remained in the line in the form of two weak companies. The Frikorps had become combat ineffective, and in early August the decision was made to withdraw it for rest, refit, and to receive replacements.

The accomplishment of the Danes had not gone unnoticed, and General Walther von Bockdorff-Ahlefeldt wrote and thanked them for their courage: “Since the 8th of May the Danmark Legion has been positioned in the fortress. True to your oath, and mindful of the heroic death of your first commander, SS-Sturmbannführer Christian von Schalburg, you, the officers and men of the Legion, have always shown the greatest bravery and readiness to make sacrifices, as well as exhibiting exemplary toughness and endurance.

“Your comrades of the Army and Waffen-SS are proud of being able to fight shoulder to shoulder with you in the truest armed brotherhood. I thank you for your loyalty and bravery.”

After this endorsement, the Danes were withdrawn to Latvia at the beginning of August before heading home to Denmark for a homecoming parade through Copenhagen and three weeks of leave. The Frikorps had been in combat for three months without a break, and in that time they had lost two commanders, a sizable number of junior officers and NCOs, and hundreds of men.

According to the latest source on the subject, they had flown into the pocket with a fighting strength of 24 officers, 80 NCOs, and 598 men back on May 8. Only 10 officers, 28 NCOs, and 171 men were able to take part in the Copenhagen homecoming parade. Some of those who were missing from the parade were wounded and still in hospitals. There is no doubt, however, that the Frikorps was decimated in the Demyansk Pocket.

They had acquitted themselves well. The SS Totenkopf’s Order of the Day on August 3, 1942, credited them with killing 1,376 Russians and capturing 103 others along with over 600 heavy weapons. While this recognition was gratifying, it did little to raise the morale of the survivors, who were heckled and mocked by some of the anti-German crowd watching them march through Copenhagen.

Postscript for the Demyansk Pocket

The Demyansk Pocket was a source of constant concern for Army Group North. In a personal letter on September 14, 1942, Küchler attempted to persuade OKH that continuing to hold the pocket was useless. The II Corps, he wrote, had been fighting under adverse conditions since the previous winter. He worried about what might happen as winter was again approaching, and he desperately needed divisions in the salient to form reserves for both the Sixteenth Army and the army group.

General Franz Halder, OKH’s Chief of Staff, answered a week later. He recognized that the army group would gain 12 divisions by abandoning Demyansk but pointed out to Küchler that such a withdrawal would also free 26 Russian infantry divisions and seven tank brigades. In any case, it was all academic since Hitler’s Haltenbefehl (hold order) remained unchanged.

The Russians continued to attack the corridor linking the pocket to the main German defensive lines. The whole pocket was under continuous attack from November 1942 and, by mid-January 1943, the fighting had drained off the last army group reserves. General Kurt Zeitzler, the new OKH Chief of Staff, told Küchler on January 19, 1943, that he intended to raise the issue of evacuating the Demyansk Pocket with Hitler.

Army Group North had just suffered a serious setback south of Lake Ladoga, and Zeitzler and Küchler agreed that the principal reason for the setback was the shortage of troops; the only way to avoid similar mishaps in the future was to create reserves by giving up the Demyansk Pocket. To both officers it was a foregone conclusion that Hitler would adamantly resist such a proposal.

However, on the night of January 31, 1943, after a weeklong debate, Hitler finally accepted Zeitzler’s arguments. The earlier setback around Leningrad may have influenced Hitler’s change of mind since he was anxiously trying to keep Finland in the war and this involved holding around Leningrad.

OKH informed Küchler that it had been very difficult to get this decision and asked Küchler to withdraw quickly before Hitler changed his mind, but a quick withdrawal risked losing the vast quantities of equipment and supplies brought into the pocket over the past 13 months. Küchler decided to conduct a slow withdrawal that began on February 20, after three weeks preparation. He then collapsed the pocket in stages, completing the last on March 18, 1943.

Postscript for the Danish SS

After a month’s leave in Denmark, the Frikorps returned to the front in November 1941. It was originally intended that it join the 1st SS Brigade in Byelorussia, a unit infamous for its indiscriminate killing of civilians in areas associated with Soviet partisans. However, the deteriorating situation on the Eastern Front caused both the 1st SS Brigade and the Frikorps to be sent to the front at the Russian town of Nevel, some 250 miles west of Moscow. By the spring of 1943 the Frikorps had suffered so many combat losses that it was down to just over 630 men. It was withdrawn from the front line.

In the summer of 1943 the Danes from the Frikorps and SS Division Wiking were united in the new 24th SS Panzergrenadier Regiment Danmark of SS Panzergrenadier Division Nordland. Most Norwegians who had served in Wiking and other units were likewise united—in May, before the Danes joined them—into the 23rd SS Panzergrenadier Regiment Norge and also in SS Panzergrenadier Division Nordland. The third regiment was SS Panzergrenadier Regiment Nederland.

At the end of August 1943, most of the 3rd SS Panzerkorps, to which SS Division Nordland was assigned, was moved to Croatia to take part in antipartisan warfare. In December 1943, the unit was again moved north to the Oranienbaum Pocket southwest of Leningrad.

From there the division participated in the German retreat to Estonia and later to the Courland Pocket in Latvia. In January 1945, it was evacuated from Courland to Pomerania and, the next month, participated in the Sonnenwende Offensive before retreating to the Oder River north of Berlin. Already heavily decimated, SS Division Nordland retreated toward Berlin.

The remnants of Norge and Danmark, in a mixed battle group, fought in Berlin in late April and May 1945 alongside volunteers from the rest of Europe. The group was obliterated in the fighting for the German capital.

Most writers hold that about 2,000 Danes lost their lives on the Eastern Front. As a comparison, a recent book by Eirik Veum identifies 877 Norwegians who were killed on the Eastern Front. This number includes 21 frontline female nurses. But both the numbers for Danes and Norwegians are open to question. For example, a controversial memorial recently erected in Denmark—in central Jutland between the cities of Randers and Viborg—asserts that 4,000 Danish lives were lost on the Eastern Front.

Despite having authorized the Danes to serve in the Waffen-SS, the Danish government on June 1, 1945, a month after the war, adopted retroactive laws criminalizing various forms of collaboration and made armed service for Germany punishable. About 3,300 former soldiers were sentenced under this new law and served an average of two years in prison. n

Danish volunteers were still at training centers when the Finnish Winter War ended in March 13, 1940. Thus, they didn’t participate in fighting in Winter War.