By Adam Makos & Marcus Brotherton

On August 6, 1942, the men of Maj. Gen. Alexander Vandegrift’s U.S. 1st Marine Division watched from the railings as their troopship, the USS George F. Elliott, steamed into the waters north of Guadalcanal in the South Pacific’s Solomon Islands. They had come to seize the island’s semi-completed airfield at Lunga Point from the Japanese before it became operational. With Guadalcanal’s airfield, the Japanese could bomb the shipping lanes to Australia and choke the continent, putting Australia at risk for Japanese invasion.

Among the thousands of troops nervous with anticipation about the battle to come were four Marines from H Company, 2nd Battalion, 1st Marine Regiment––Jim Young, Sid Phillips, Roy Gerlach, and Art Pendleton––dressed in their steel helmets and green cotton-twill uniform (the Marines’ familiar, mottled-green camouflage uniforms had not yet been issued). This is their story.

“This was the real deal.”

Jim Young: “We were awakened around three in the morning on August 7, 1942, the day we were to fight the Japs. Breakfast was at 5:00 am. The food was steak and eggs. After eating, which was hard to do, we went up on deck to watch the bombardment of Guadalcanal. It was unbelievable, and the noise was horrendous! Most of us were scared and bewildered. We couldn’t even hear each other without yelling.

“We received orders to go below and get everything ready to disembark. The sea was rough and dangerous. Due to the waves, boats were dropping six to 10 feet, just as men were ready to get in them. Or if the boat didn’t drop, it came roaring up. A man was crushed between the landing craft and the side of the ship. Lots of guys were hurt that way.

“One of the men from my gun crew, a Marine Pfc., had made it into the landing craft and had his hand on the craft’s rail when our wiremen stated to lower metal coils of communication wire from the ship. A line broke and the heavy coil of wire hit his arm and snapped it. They hoisted him back aboard.

“It was go time. The engines on the landing craft were all roaring at full throttle. We were on our way in and everyone was nervous.”

Sid Phillips: “There was a flag flying on the stern of every landing craft. I looked over the side at the flags, and my friend Carl Ransom was doing the same thing. You could see a whole line of them. It looked like they reached to the end of the world. I got a lump in my throat. Ransom did, too. As he wiped his eyes, he said, ‘That salt spray makes your eyes water, don’t it?’

“We had never had that happen before, never in training, and I never saw it [a U.S. flag on every landing craft] happen again after that. They were too good a target. A big old red, white, and blue thing like that shouts, ‘Here I am! Here I am!’ Our Colonel Cates [Clifton B. Cates, CO of the 1st Marine Regiment] was a very patriotic Marine. If there was an order given to fly a flag on every landing craft, I’m sure Cates gave that order.

“I noticed that morning how everybody’s cartridge belt was full and bulging. You could see the shiny brass cartridges here and there in the belt. You had two clips of five rounds in each of those pockets. When we had made practice landings in the Fiji Islands, they never issued any live ammunition. We made the landings with empty, flat, cartridge belts. They didn’t want some idiot firing his rifle into someone. Things were different now. This was the real deal.

“When we came ashore at Guadalcanal, we were in that landing craft where the front end would drop down…. We had the front ramp because otherwise we couldn’t get that mortar out of the boat. We were expecting a life-and-death struggle with hand-to-hand combat on the beach. When the ramp went down, we found our guys on the beach laughing at us and opening coconuts. We came out of the landing craft ready to fight and they just laughed. They had done the same thing a few minutes before. There were no Japs in our vicinity at all.”

August 7, 1942, only to find no initial enemy opposition. Most were expecting stiff resistance on the beach.

Roy Gerlach: “I didn’t go in on the first wave. I was a mortar man assigned to the mortar platoon, but I spent a lot of time as a cook. In the Marine Corps, you were assigned to the job you were supposed to do, and then if you could do something else, you did that, too. Whenever there was action, I was on the mortars. But if they needed a cook, well, I did that, too….

“I don’t remember much about coming in to the beach. There were no Japs there. They’d all taken off to the hills. Right away we found all these coconuts. They fell out of the trees. We took our bayonets, bored holes in the coconuts, and drank the milk. But it made the guys sick. Too much fresh milk, I guess.”

“The heat was so oppressive.”

Sid Phillips: “All the first day we struggled through the jungle to reach a hill called the Grassy Knoll, a mile inland. We had no good maps for Guadalcanal at all. They had some maps drawn up by some Australian people who had been on Guadalcanal. These crude maps were named by the Australians. They even had the names mixed up for the Tenaru and Ilu Rivers.

“So the game plan was to go to the Grassy Knoll and get the high ground. The thing that stands out so clear in my memory was the heat, the incredible heat in the jungle, with no breeze. And we had just come from winter in New Zealand, so it was a severe climate change. We just griped and bitched. In that jungle, it’s so hot, and you’re carrying a 60-pound pack when you come ashore. Extra ammunition, packs of food for four days, a change of clothing. You drop your bedding and keep going. The heat was so oppressive.

“We were issued one canteen then. We’d been taught water discipline. You were only supposed to take small sips of water and roll the water around in your mouth before you swallowed. You were never supposed to guzzle water. Everybody nearly died of thirst that first day. We ate crackers, cans of hash—there was no water in the food; it just dried you out more and made you more thirsty. At the end of the first day, we were exhausted, halfway up the Grassy Knoll. They told us to lie down where we were, dig a foxhole, shut up, and go to sleep. So we did.”

annihilation was inevitable.

Jim Young: “When morning came, we were ordered back to the beach to set up defenses in an effort to repel any Jap attempt to land. One of our lieutenants was bitten in the face by a scorpion during the night. He had swollen up so much that he was completely blind and had to be led by the hand on the long march back to the beach.

“As we approached the beach, about 10 Japanese torpedo bombers skimmed the water and headed for the convoy. They were so low we could see the faces of the pilots and the big red meatballs on their wings. They did not care about us on the beach. They went straight for the convoy of ships. One plane headed directly for our ship, the Elliott. It crashed into the water first and bounced up and slammed into the ship.”

Roy Gerlach: “We didn’t have no galley for the first three or four weeks because our cooking equipment sunk with the Elliott. I wasn’t on the ship then, but I saw it all. Most of the troops were on shore by then. But the unloading of the ship wasn’t done yet. There was one shipman I knew on the Elliott. He always used to say, ‘I’m gonna be here when you go, and I’ll be here when you get back.’ He wasn’t.”

Sid Phillips: “People ask me when we first contacted the enemy. We were strafed by enemy planes almost immediately on Guadalcanal. You dig a foxhole and try to dig it as deep as you can, just try to bury yourself with the earth. The strafing never ended on Guadalcanal. They were always coming in, bombarding us. We considered that contact with the enemy.”

Jim Young: “The Jap Zeros would come swooping over us. I could actually see the pilots, the faces in those airplanes. You could see them turn their heads and look down at you. Sometimes they were grinning.”

“The Savo sea battle was like watching a summer storm from a beach.”

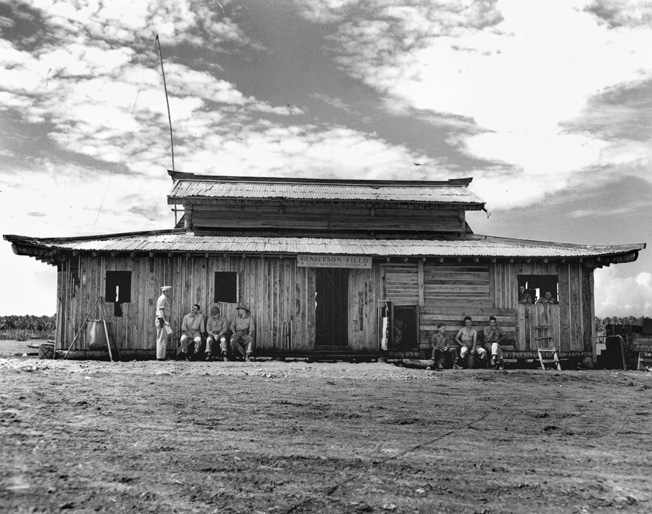

Sid Phillips: “The day after we landed, we captured the airfield. When I first saw the airfield, I was surprised that there weren’t many buildings except for this pagoda-looking thing. That served as the tower. The runway wasn’t very visible unless you were up in the air. There were no wrecked Japanese planes. The place was empty. We went over there and looked at the pagoda. We were some of the first Americans to walk into that building.

“The first American planes we saw come in there were the B-17 Flying Fortresses. Sometimes two, sometimes three. They would stop, refuel, and leave. The Flying Fortresses came in before we had any Navy or Marine planes at all.”

On August 9, from its bivouac on a hilltop over the beach, H Company witnessed a violent naval battle between the U.S. and Japanese navies. This, the Battle of Savo Island, produced so many sunken ships off the island’s shore that the waters gained the name Iron Bottom Sound.

Sid Phillips: “The Savo sea battle was like watching a summer storm from a beach. You would hear this rumble of naval gunfire and see what looked like flashes of lightning. You’ve seen distant lightning where the sky lights up? It was that sort of thing. You couldn’t see any real details of the naval battle, but when a ship would blow up, we cheered. We assumed it was our boys doing the whipping. The next morning we saw one American cruiser creep slowly by, right offshore, with part of its bow blown off. Somebody said it was the Chicago.

“We were then told about the disaster. We lost four cruisers that night. You could maybe see a ship smoking, three miles away. Our supply ships were still in the harbor, but they were pulling out. Leaving us. They hadn’t even unloaded half our supplies. But they had to get the hell out of there.

“At that moment we felt that we might be considered ‘expendable.’ It had occurred in the Philippines. It had occurred at Wake Island. It had occurred at Guam. It had occurred at every stage of the war in the Pacific up to Guadalcanal, so yes, we felt expendable.”

Jim Young: “Without our ships, we were alone on the island. There was no food except for what we had in our backpacks––K rations. After sending out search parties to look for food, we found stores of Japanese rice and oats which would hold us over until the Navy could return with more supplies. It took a strong stomach to eat this because the rice and oats were crawling with maggots and worms. We found that if we dumped the rice and oats in water then all the bugs would float to the top where we could skim them off.

“We bivouacked at the end of a coconut plantation, near a meadow with a patch of trees. The trees were lime trees, and we made limeade. We used warm water and we had no sugar. This stuff was terrible, but it was something different to drink. This meadow had the oddest plants I’ve ever seen. If you took a walk through them, it looked like a well-worn path, but 20 minutes later there was no trace of where you’d walked.

“In the days that followed, we still hadn’t seen the Japs up close, but the air raids continued. We had an old gunnery sergeant, 50 years old, real nice guy and a real Marine. We called him Gunny Dixon. Gunny told us to dig foxholes. When we were finished, he took one look at them and started to laugh. ‘Well, well,’ he said. ‘They don’t look deep enough to me. I bet by the end of the week they will be deep enough to stand in.’ How right he was! Bombers flew over us, and we couldn’t do a thing about it. We had no guns that could reach them, and we had no airplanes. The bombs falling had a whistling sound as they came down.

“One day the Jap bombers came from a different direction. They had always bombed the airstrip from the takeoff point to the liftoff point, but this day they came straight from the sea toward our tree grove. This time they were after us, and not the airstrip. I was watching them with field glasses, and I could see the pattern of bombs exploding and knew it would surely hit us. I yelled a warning, and we just made it to our foxholes in time. It was impossible to stand in the foxhole. The earth was shaking like an earthquake. Big chunks of earth filled the air, and the smell of cordite was overpowering. It’s hard to believe that no one was killed.

“We found a Jap bunker near us that held about 20 of us. It was very dark inside, and while using it during an air raid one day one of the guys let out a loud scream. It scared all of us, and we scrambled for the exit even though the air raid was still in progress. A six-foot-long lizard was up on the roof of the bunker, and its scaly tail had flopped down and touched the Marine’s face. He thought it was the guy next to him so he reached up to brush it away. When he felt the tail, he went ape. We all got a kick out of it when it was over.

“At night the Japs sent a lone bomber that kept flying around for hours before he decided to drop his bombs. They did this to keep us from getting any rest. We called him ‘Washing Machine Charley’ because of the sound of his engine.

“The bombing raids never ceased. After a while, we were shelled from Jap cruisers and subs as well. What made us mad is that we could see the Japs scurrying around their decks and manning the guns. But we had nothing that we could reach them with. All of our long-range guns were on the ships that took off when the naval battle took place.”

“… the next night the whole island seemed to be deserted…”

Sid Phillips: “The rifle platoons, they had daily patrols. Fifteen to 20 men would go out with an officer, scouting, trying to find out if there were any Japs in a particular area. In the mortar platoon we seldom went on patrols.

“But we did go out after a Marine patrol had been ambushed and the survivors came back to our lines. So they put together a 300-man patrol to go back out there to recover our dead. They wanted one 81mm mortar to come along, so they came to the mortar platoon and said, ‘Number four gun is going.’ That was me. Lieutenant “Benny” Benson, he was the lieutenant for our gun, went with us.

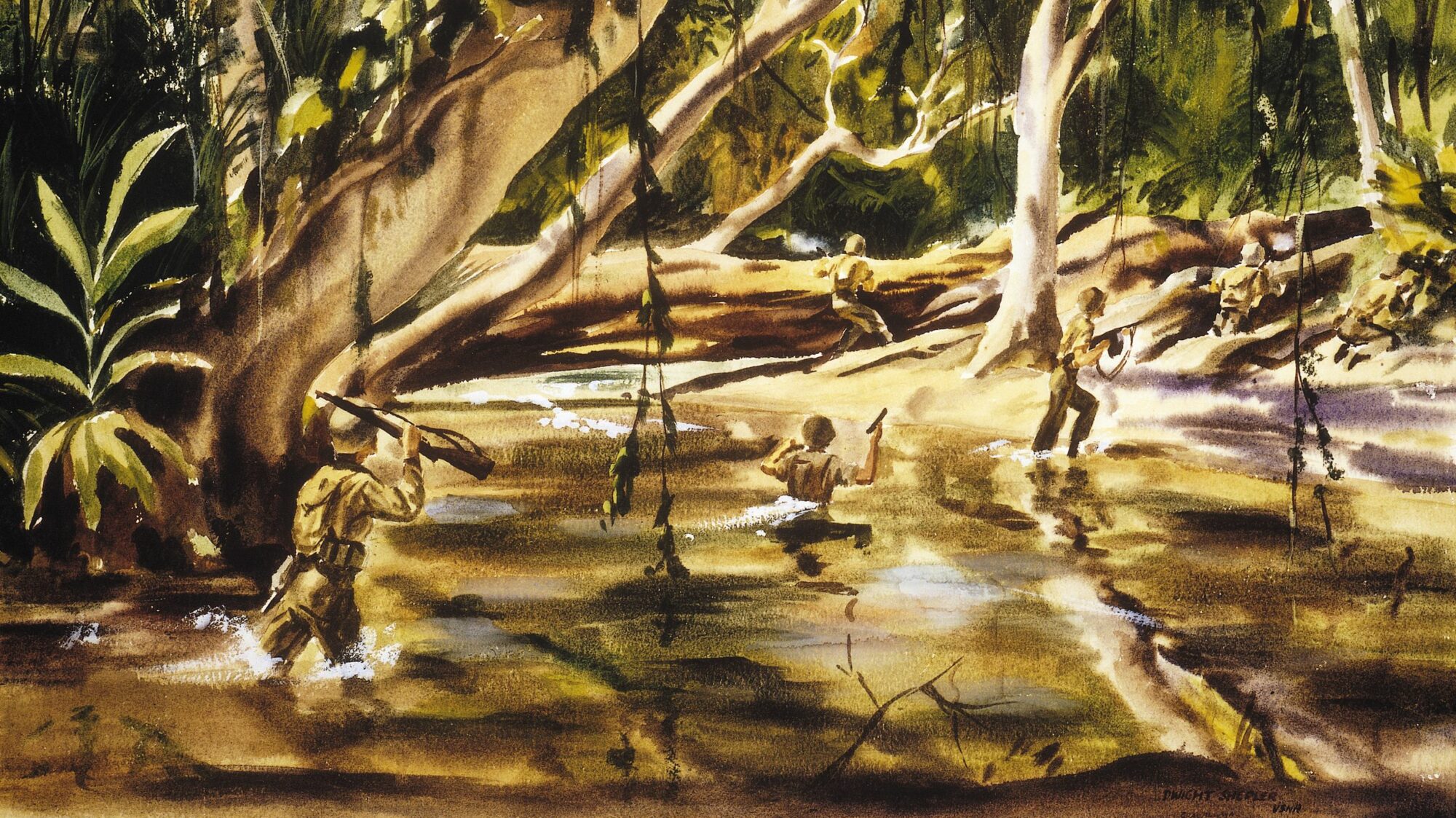

“The riflemen were on the point, watching for the enemy. In the mortar squad we trudged along behind them with that damn heavy stuff. We went about five miles out, carrying that mortar the whole way. You either carry part of the mortar or the ammunition. If you were an ammunition carrier, you carried a cloverleaf of ammunition on your shoulder.

“It was a strenuous march in the tropics. There were no roads. To be on the ground in a dense jungle, you did not even need to see combat to have a miserable time. You might have hiked way out and way back and had to ford several streams and walked through water waist-deep where your clothes got soaked and your feet didn’t dry out and your pants chafed your crotch. You just can’t convey that misery in words.

“When we reached the area where the ambush had occurred, the mortar platoon stopped 150 yards from the site and set up our mortar. If the Japs were gonna ambush this big patrol, we were gonna give our guys mortar support. You could just look where our guys were, and we would have fired beyond them. But the Japs had vacated the area.

“We never did get up to the actual site of the ambush, but this old Marine sergeant came walking back, and Benny knew him real well because Benny was an old Marine, too—30 years old was ancient in our minds. Benny said, ‘What’s the scoop up there?’ and this sergeant said that all the Marines had been beheaded and had their genitals stuffed in their mouths. They brought our dead back on canvas stretchers, their bodies covered by ponchos.

“Our hatred for the enemy burned from early on. We had heard about the Bataan Death March, where they bayoneted American prisoners who fell exhausted by the roadside. We had talked to the 90mm antiaircraft battery that was near our bivouac—they were a defense battalion that had been at Pearl Harbor.

“Then there was the Goettge patrol. A few days after we landed on Guadalcanal, some Jap prisoner told Colonel Frank Goettge that the Jap’s buddies wanted to surrender five miles west of our lines, where the Matanikau River met the sea. Goettge took a patrol of 25 men out to take their surrender. But it was an ambush. Goettge and his men were butchered. Only three of them escaped by swimming back to our lines.

“Was he an idiot for thinking the Japs would surrender? No, we just didn’t really understand the enemy yet. Surrender was out of the question for a Jap unless he was knocked unconscious. But even then, if you saw an unconscious Jap, you’d be very cautious because he might be only pretending. He might try to kill you.

“Japan soon proved a brutal enemy. They ignored the Geneva Convention. They tortured prisoners of war, then killed them. Hell, they would torture a body and mutilate it even after a guy was dead. A hatred between the Marines and the Japanese rapidly developed. We never took a prisoner, never in my battalion, that I know of.”

On August 20, bad news came to the Marines, word that the Japanese were landing fresh troops to retake the airfield. That same day a new armada of planes was heard in the sky.

Sid Phillips: “It was late in the afternoon, and we were at our mortar position when we heard airplanes circling the field. We ran for cover. They came in from the south over those ridges. The roar of all the airplanes was deafening. They were loud by themselves, but when you have the sky full of them—wow! Someone screamed that they were our planes.

“We just went wild. I looked up and saw a blue-gray SBD dive bomber with the letters ‘USMC’ painted on the underside of the wing. We flung our helmets way up in the air. We were beating on each other. Some of the guys were crying with joy they were so happy. We hadn’t had any friendly planes except those two or three Flying Fortresses that came in. We had been strafed regularly by the Japanese Zeros. Seeing our planes told us that Uncle Sam had decided we were going to fight for this miserable island.”

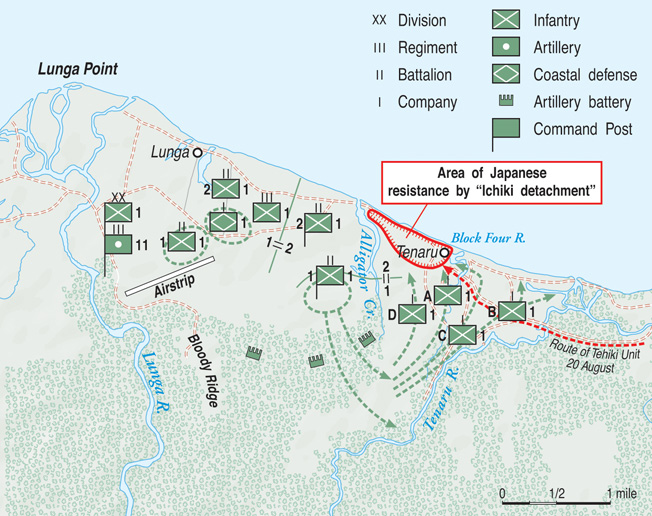

On August 21, 1942, the Marines and the Japanese Army would meet in the first major battle of Guadalcanal. The Japanese had landed 900 soldiers of the elite Ichiki Detachment, who marched west along the beach, toward the airfield. The Marines of H Company waited for the enemy along the west bank of a small river they called “Alligator Creek,” or “the Tenaru.” [Actually, the stream was the Ilu River.]

Jim Young: “We took turns manning defense lines at night. It was scary. The jungle was thick in front of us, and the nights were black. We heard all kinds of noises, and some of us would fire a few rounds in front of us just in case Japs were sneaking up on us. The trouble was that everyone got jumpy when someone fired, and the whole line would open up. You would think a hell of a battle was going on.

“Well, the general got fed up with all the shooting and nothing to show for it. He issued an order that if any more of that wild firing happened, he wanted to see dead Japs, or that unit would catch all the working parties. Let me tell you, the next night the whole island seemed to be deserted, it was so quiet. The only sound came from ‘Washing Machine Charley.’”

“The Battle of the Tenaru [River] was the first real fight on the island.”

Sid Phillips: “The Battle of the Tenaru [River] was the first real fight on the island. Our lines ran north and south from the ocean back to where the airfield began. We did not have a perimeter around the airfield; we didn’t have that many men.

“We were stretched out in these holes, every seven yards, two men with rifles, two men with rifles, then maybe six men with a machine gun, their position covered with logs and dirt, then two men with rifles, and two men with rifles, and so on. The jungle around you was so thick, you didn’t know who was where, or what was where. You would lie there and listen to all those different damn jungle noises.

“One of those iguanas, three feet long, could be scurrying around, wrestling and making noise. You would wonder, Is that a damn Jap or is that an iguana? So you stayed awake. You didn’t want to give a false alarm. After a while, you would get used to it, and you began to take pride in the idea that you could tell a land crab from a creeping Jap, you know.

“The mosquitoes were eating us alive. There was no repellent or anything. We just lay in those holes and fed those mosquitoes all night long. We’d been living on rice and nothing else for a long time there. Everybody was wore out, exhausted before long. Every two hours you were supposed to switch off on watch with the guy in your foxhole. We were always on edge.

“Because things were so spooky, they would take our squad leader, Sergeant Carp from Brooklyn, and put him up on the perimeter. He carried the BAR [Browning Automatic Rifle], and they wanted his firepower up there. Plus, he had been in the Marine Corps about three years and was an old timer that they considered much wiser than us kids. They put him up on the perimeter every night with that BAR.”

On the H Company line, a Marine named Art Pendleton led one of 12 machine gun squads.

Art Pendleton: “I was a corporal. I had joined the Marine Corps in January 1942 in Worcester, Massachusetts. Before that I was a pretty ordinary guy, a country boy from central Massachusetts—horse-and-buggy country. I enjoyed school. Never had any such thing as an affair with a girl (until I got into the Marine Corps). Never would touch a drop of alcohol. Never even heard of drugs. It was a whole different way of life. Women were also much different. If you ever saw a woman in the barroom in our town, it would be a story to tell.

“That all impacts your character, I suppose. When I boarded the train in Boston to go to Parris Island [the Marine Corps’ boot camp and training center in South Carolina], there were lots of other men there from all over New England. One fellow who ended up in H Company with me came from Southborough, Massachusetts, which was just a short distance from where I lived. His name was Whitney Jacobs.

“Jacobs was a hairy little guy and powerfully strong but not the kind of person that you would think of being a Marine. The rules and regulations for joining at that time were stringent. You couldn’t be an African American, which was sad. [Not until June 1942 did the Marine Corps accept its first black recruits. By the war’s end, more than 19,000 black Marines would serve with distinction.]

“You had to have all of your teeth except for two, you had to be a certain weight, a certain height, you had to have certain education, and the list goes on and on. You wouldn’t think that little Whitney Jacobs would have ever made it, but he did.

“The night of our first battle with the Japanese, our machine-gun emplacement was on the beach looking out at the ocean while others were on the riverbank. There was only one likely place that the Japanese could breach our lines—the sandspit. The sandspit was part of the beach that separated the river from the ocean. The sandspit was like a dam. The river trickled over it all the time. The only time the river would run freely over it was when I suppose there was a heavy rain.

“Right behind the sandspit the river got deep. We knew the Japanese could walk across that bit of sand if they attacked, so we strung some barbed wire on some poles there. It was like a 90-degree angle. We were about the only gun that was that close to the sandspit.

Whitney Jacobs, who was a rifleman, was near the river. Riflemen and the machine guns and BARs were right up front. Whitney thought that he heard something out of place in the night. He fired without waiting for orders. That one shot started the battle because the Japanese were there, trying to cross the river.”

Jim Young: “Around 1:30 am on August 21, a few shots were fired up on our defense line at the Tenaru River. The tempos of firing increased with a few machine-gun bursts. Then all hell broke loose.”

Sid Phillips: “The Japanese unit had come marching down the beach, moving west, and when they got to the Tenaru River, they spread out and formed a front. Some of them waded through the creek quietly. It was black as dark. When the Japs hit, Sergeant Carp and his foxhole companion, a Marine named Beer, had fallen asleep. They were just so exhausted and so tired. A Jap officer jumped in their hole and hacked them up, killing them both, until someone shot him. When the firing started, the darkness became almost as bright as day. A wall of fire poured from our lines. A real roar. We knew the real enemy was here. They were disciplined and vicious.”

Art Pendleton: “The Japanese had landed nearly 1,000 men of the best that they had from the Ichiki Detachment. They tried to come across the sand first but ran into our barbed wire, so they had to cross the river. It was neck deep in spots. The Japanese put themselves to a big disadvantage from the start.”

“Marine, tonight you die!”

Jim Young: “A screaming horde of Imperial Japanese soldiers tried to cross. They came in waves of 50 and 100 men at a time. We had about 90 men on the defense line.

“Japs who could speak English were screaming, ‘Marine, tonight you die!’ and ‘Blood for the emperor!’ We started yelling back at them, ‘F—k your emperor!’ and ‘Go to hell!’––anything we could possibly think of.

“The Japs threw coconuts in the river. That way, it was hard to tell if you were shooting at a coconut or a Jap’s head. Then they charged across the water. Some of them got through our line and were bayoneting our men.

“On the front lines, one of my close friends, Crotty from New York, was in a two-man foxhole. A Japanese officer had snuck through the line and came at him from the back of the foxhole. The other Marine in the foxhole with Crotty had put a bandolier of ammo across the back of the foxhole and rolled onto his back to reach for it. When he looked up he saw the Jap officer with his saber raised over his head. The Marine drew his knees to his chest to protect himself. The Jap’s saber hit him in the kneecap and split his knee down through the shinbone.

“Crotty heard his buddy scream and turned around. He shot just before the Jap could bring the blade down for the second hit. The bullet went up through the Jap’s rib cage and came out under his armpit. He fell on them.

“Our lieutenant, Benson, was yelling for us to prepare to move the mortars into action. We were powerless for the moment. A mortar required light to see where you’re aiming, so we just waited, watching the flashes, praying for the hint of dawn. I thought to myself …You wanted to see Japs, well, here they are.”

Art Pendleton: “My gun was on the beach when the battle started. John Rivers and Al Schmid’s machine-gun emplacement was on the bank of the river. John Rivers was a very nice guy and very tough––a former boxer. He had given up a chance to be a champion lightweight prizefighter to enlist instead.

“We had four heavy machine guns in our platoon, and his happened to be right in the spot where the Japanese came across the river. John was right in the middle of it. The Japanese never should have hit us there. They were in water up to their neck getting across the river. Hell, they were fodder for us.”

Jim Young: “John [Rivers] was the gunner and Al [Schmid] was his loader. Even though they had boxed one another on the deck of the ship, they worked together well. Their gun was in a sandbagged pit on the riverbank, and the Japs were attacking them like herds of cattle. Johnny was mowing them down until he was shot in the face and killed.

“Al took over as gunner and kept fighting until the Japs threw a grenade into his gun pit and wounded him and his ammo bearer. Blinded, Al resumed firing with the ammo bearer shouting in his ear, directing his fire.

“A guy from North Carolina named Pfc. Steve Boykin, a very nice gentleman, got hit up there on the line. His one leg, the whole back of it was almost blown out. His men slid him back off the line and set him against a tree. One of the Japs got through and got to him and stuck him with a bayonet but didn’t kill him. The Jap was killed. Somehow Boykin survived.”

Art Pendleton: “As the battle raged on, Whitney realized that one of our machine guns had stopped firing, the one that had been devastating the enemy. You can’t fire a machine gun steady because if you do the enemy will zero in on you. But when you’re in that kind of a situation, you don’t use common sense. You’re firing for your life.

“Whitney crawled a few feet to the silent gun emplacement. He stayed on his stomach and peered into that emplacement and called out. Inside, John Rivers was dead, and Al Schmid, who was blinded and in bad shape, answered him. Whitney shouted, ‘Don’t shoot—I’ll go get help.’ So he backed off and reported to the officer in charge. Right away our lieutenant called my gun in because I was about 100 feet from that point.

“We rushed to move. The gunner carried the gun, and the assistant gunner carried the tripod. When running up to the line to get a look at where we’re going, a hand grenade, I believe, went off between my legs. It lifted me up in the air a little bit, but it didn’t touch me. I thought, Wow! How lucky can you be?

“Everything seemed so confusing. We were directed to Rivers’ gun position. No one was in it. I don’t know where Rivers’ body went or where Schmid went. They were destined to get knocked out because they were firing so heavily. Rivers’ gun was totally destroyed, so I just threw it out of the emplacement. That machine gun killed many, many, many Japanese. I put my gun in its place. We were in the middle of it now.

“The Jap officers had these fancy sabers and were swinging them in the air trying to scare the hell out of us. Our guys were way beyond being scared. They were there to kill everybody. You forget about being scared when your life is at stake. There’s no such thing as scared.

“I started firing as soon as I got the gun set up. If you didn’t, you were going to get killed. Rivers’ position was the focus of the whole Japanese attack. The Japs were all over the place.”

“Those flares were probably one of the most dangerous things in the battle.”

Sid Phillips: “As the battle raged, our 81mm mortar platoon––all four tubes––was facing the beach in case there was a landing coming in from the ocean. So the attack was coming from our right flank. Our lieutenant moved us toward the battle, up parallel to the river. Our foxholes were all over. Our machine guns were so well dug in you could hardly see them at all in the dim light. As we moved up in the dim light, we kept falling in foxholes. To fall in a foxhole with a mortar tube or base plate can be painful as hell. It could kill a man if it fell on him.”

Jim Young: “We set up the mortars in the coconut grove parallel with the river. We had no defensive cover for protection. It was like being in the middle of a football field. We had to work fast because the Japs spotted us and started shelling us. The lieutenant was worried that we may not have enough clearance through the coconut leaves. I told him I thought I could get through. I fired the first round and knocked a palm leaf off a tree, but the shell didn’t explode, so the lieutenant gave the order to ‘fire for effect.’ This means to fire as fast as you can.

Sid Phillips: “There was a pile of Japanese dead right out in front of our new mortar position, about 30 yards away. They had killed them before we got up there. We were trying to hit an area about the size of six football fields on the other side of the river. We just kept blanketing the whole area over there.”

Roy Gerlach: “Our front lines kept the Japs backed up in the river. I was with the 81mm mortars; I carried shells to the guns. Our mortar fired a three-inch-wide shell that you dropped down into the tube and it shot up into the air. It reached out over our lines and came down and killed anyone for 30 yards. No, it never bothered me being a Mennonite and being in the war. I guess I was more broadminded.”

Art Pendleton: “The thing that impressed me more than anything were the flares. When they would shoot a flare in the air, you could hear it pop when it lit. When they ignited, it was a very bright light. Then the parachute opened, and the flare would very slowly float down to earth. No matter what you were doing, everybody stopped. You didn’t move a hair. If you dared to move, you were going to get shot. We lit flares, and so did they. It was just to check positions and see who was where. Those flares were probably one of the most dangerous things in the battle.”

Sid Phillips: “We were firing heavy, 15-pound shells. It is a deafening explosion when that thing goes off. You just can’t believe it. If you shot the biggest firecracker ever, it was a thousand times louder than that. We were actually awed by the results of that 15-pound shell. At Camp Lejeune we had one day of firing live ammunition, but the range was over 2,000 yards away. We had never had any close-up firing until that battle.”

Jim Young: “We saw Japs, their clothes on fire from our mortar bursts, running to the sea and river to put the fire out. Our number-four gun had a misfire and had to be taken out of action; Corporal Mugno’s ramrod for cleaning the mortar tube had a sock wrapped around the end of it that came off and fouled the gun. It was utter chaos.”

Art Pendleton: “At one point they tried to flank us at the sandspit. My gun wasn’t shooting at the sandspit at all since that was covered by another gun on our left. That was also covered by the 37mm cannon. The 37mm was a lightweight cannon, but they had canister shot for it, the same as you would shoot game birds with. It was not one bullet; it was many pieces of metal flying through the air, like a giant shotgun. It was firing again and again.

“I wasn’t worried about the sandspit. I wasn’t even thinking about it. We had our hands full just taking care of what was in front of us. They had to cross the river and climb up the bank in order to get to us. We slaughtered them.”

Sid Phillips: “During the battle, Colonel Pollock [Lt. Col. Edwin A. Pollock, CO of the 2nd Battalion, 1st Marines] came running over to our gun and said, ‘Who is the gunner here?’ I held my hand up and he said, ‘Well, boy, use me as the range stakes.’ He ran out about 40 feet in front of the gun and held his hand up. I put the sights on zero deflection, and we dragged the gun so that we had him lined up. Then I noticed beyond him through the trees was an abandoned American amphibian tank on the enemy side of the river. The Japs had gotten a machine gun into that thing and were firing from inside it.

“Pollock said to try 300 yards. Our shot was right on, but it was a little bit beyond the target. We lowered our mortar down, and our third round landed right in the tank. Everybody along the line cheered like a touchdown in a football game.”

Art Pendleton: “Near the end of the battle, Colonel Pollock, who was a great man, came to me and said, ‘Stop firing.’ I said, ‘I’m trying to take out a couple of guys that I’m seeing running there.’ He said, ‘Don’t. We don’t know what’s over there, and we might open up another Rivers situation here.’ He knew the fight was over and didn’t want us getting ourselves killed or the other Marines who were surrounding the enemy from different directions at that time. He was our colonel, and I respected him a lot.”

Sid Phillips: “The Japs tried to pick us off with a 75mm howitzer cannon they had wheeled up. It had iron wheels on it, and they drove us away from our mortar once. They also fired those grenade launchers, those knee mortars, at us. When those things went off, it sounded like you had slapped two pieces of two-by-four together. A crack! And if it hit close it would scare the hell out of you.”

“… the Jap dead were piled three to five feet high.”

Jim Young: “The battle wound down, and it grew light. In the end, the Jap dead were piled three to five feet high. There must have been a hundred or more bodies in front of our 37mm cannon that was located on the sandspit, which was the only way the Japs could attack without going through the creek.”

Art Pendleton: “I can remember looking at these Japanese soldiers who were caught in the barbed wire, and their heads were blown open and the brains and innards was dripping out of their heads. That scene is still with me nearly every day, 70 years later.

“The Japanese soldier was very different from what you would consider the Japanese population. They’re a kind, generous, easygoing nation of people who love nice things and are very delicate in their artistry, music, and everything else. Their soldiers, however, were brainwashed to the point where suicidal attacks were nothing for them, nor were acts of unspeakable brutality. We were a bunch of American kids. Our social system was different, and we were brainwashed, inasmuch as you do what you’re told to do and don’t question orders, but if someone told us to throw our lives away we weren’t ready to give it up. There’s a big difference.”

Jim Young: “Two hundred bodies were piled up in front of the gun position of Johnny Rivers and Al Schmid. Schmid survived the battle, although he was blinded. I could hardly believe I was seeing so many dead enemy soldiers. Some just looked like they were sleeping. Others were mangled. Some were burnt.”

Sid Phillips: “General Vandegrift and his staff came right up behind our guns. Vandegrift was the top dog on Guadalcanal. He was within 10 feet of us. A corporal followed behind General Vandegrift with a 12-gauge pump shotgun, and he kept the shotgun at port arms; I don’t even know if it was on safety, but all he had to do was point that thing and fire it. He stayed right with the general, and that’s when my buddy Ransom said, ‘Phillips, if you want to get your ass kicked, just go over there and stand between the general and that corporal.’

“Our tanks didn’t come up until maybe 10 o’clock in the morning. They passed right down the beach right there. You could have walked over and touched them. When the tanks got through, our whole 1st Battalion, A, B, C, D Companies of infantry, had circled around from the south, and they came around and drove all the Japanese survivors ahead of them out into the ocean. About 30 Japs ran out and jumped in the surf. Everybody kept firing at them until no more heads were visible.”

Jim Young: “At about two in the afternoon the next day, the temperature was around 95 degrees. We walked among them [the dead Japanese] looking for ones that were still alive. Several of our men had been shot by Japs who were only playing dead. The colonel issued orders to shoot any one of them that might be alive. The smell of death almost took your breath away. The chaplains were taking the dog tags off the dead Marines. They said we lost 40 men. It was one hell of a night, and we were glad it was over.”

Art Pendleton: “I can’t even begin to tell you how many bodies were in the river floating around after this battle. You could hardly see the water. We killed almost 800 of them. They were some of their best men that used to train on Mount Fujiyama. They’d put on full marching gear and run up the mountain and run down the mountain. We never would have won that battle if we didn’t have the advantage of the river.

“Their bodies were all over the place for two weeks. The crocodiles were ripping them apart. There were a few of them that survived and escaped back on their fast ships to the other side of the island. These men fought again, but they were all annihilated in the end.”

Sid Phillips: “After it was over, Colonel Pollock came over and told us we had done real well and shook hands with everybody.

“This Japanese unit that hit us there was half of the Ichiki Detachment, an elite unit. They first went ashore at Guam and captured our Marines there. Evidently they had gone through all the Marines’ personal gear because the Japanese packs were full of snapshots of American people—Marines and their girlfriends. We found about 100 of these snapshots after the battle.

“We collected up all the pictures of Americans and decided that the best thing to do was burn them. You wouldn’t want to send them to the families, even if you could identify them. We kept all the Japanese pictures. You’d never burn them. You could trade them to sailors on board ships for almost anything—clothes, chewing tobacco. Money had no value, but you could do a lot by trading souvenirs. I opened one Jap pack that had three Marine globe-and-anchor emblems in it. My friend Deacon Tatum got stuck with Carp’s BAR and had to clean his blood off of it.”

Art Pendleton: “I remember two riflemen, who were my friends. A big shell landed beside them and killed them both. It didn’t just kill them, it blew them to pieces. Their names were Barney Sterling and Arthur Atwood. They would both receive the Navy Cross posthumously. Our lieutenant gathered me and a couple of guys, and we got ponchos and picked up their body parts. We carried them up through the coconut grove and dug their graves right near the end of the Henderson Field airstrip. That was the beginning of the Marine cemetery on Guadalcanal. From that time on there were a lot of graves in there. I never cared about going back to Guadalcanal, but a friend told me it’s a big cemetery now.”

The Battle of Guadalcanal went on for another six months and ended in a decisive American victory. The Lunga Point airfield was renamed Henderson Field in honor of Marine aviator Major Lofton Henderson, killed at the earlier Battle of Midway. Today the airfield is known as Honiara International Airport (see WWII Quarterly, Fall 2011). The island was not declared secure until February 9, 1943. By then the American Marines and Army had lost 1,592 men killed and 4,283 wounded, while the Japanese were decimated: over 28,000 killed, missing, or dead from disease.

The outcome of the battle also marked the end of Japanese expansion in the Pacific and, from then until August 1945, Japan was on the defensive until its final defeat.

This article is excerpted from Voices of the Pacific (Berkley Caliber, 2013).

The am 90% sure that the tall lanky armored crewman on the left was John “Jack” Ames. He was from Philadelphia and ended up in Southampton Pa eventually. When I got talking with him I described this very night to him and told the Al Schmidt story to him. He looked at me and said Al Schmidt was his first cousin. He regained partial sight eventually and worked for the Postal service and lived in South Philadelphia.

He retired in the nineties and moved to Florida. He died soon after.