By Roy Stevenson

At 4:25am in the predawn darkness of May 10, 1940, nine German gliders silently skidded to a stop on the hilltop of the most heavily defended fortress in Europe, disgorging 71 highly trained German Fallschirmjäger.

These paratroopers were about to attack what was considered the most impregnable fortress in Europe—a mission that was regarded as nothing short of suicidal. Yet, by 11:30 am the next day a Belgian officer clutching a broom handle with a white bedsheet attached, and accompanied by a trembling bugler, appeared at the entrance of Fort Eben-Emael to surrender the massive concrete fortification to the German forces. Only six German Fallschirmjäger were killed and 15 wounded, while 780 dispirited Belgian troops marched out of Fort Eben-Emael’s casemate, hands held high in surrender.

Adolf Hitler’s big gamble on this early strike of World War II had worked. The gateway to Belgium had been forced. The German offensive rolled over the Albert Canal and into the neighboring country. By May 28, after only 18 days of fighting, Belgium had capitulated and German panzers had plunged deeply into France through the green, rolling hills of the Belgian Ardennes Forest, outflanking the French Maginot Line.

Not only had Belgium fallen, but Luxembourg, the Netherlands, and France had also surrendered or were on the brink. By the end of May British and French forces would be forced to evacuate the Continent at Dunkirk. This marked the beginning of five long, dark years of German occupation until Europe would be liberated by Allied forces after the D-Day landings on June 6, 1944, and by Soviet forces coming from the east.

World War II literature is filled with examples of shock attacks where sheer audacity, combined with swift action in a surprise lightning strike, has resulted in a small number of well-trained commandos overcoming a numerically superior force of enemy soldiers in short order. Although relatively unknown outside Belgium, the Netherlands, and Germany, the dramatic lighnting strike that led to the fall of Fort Eben-Emael is, for many reasons, World War II’s most impressive example of such a shock action. Despite its relative obscurity, the classic airborne invasion and capture of Fort Eben-Emael in May 1940 is still used today at West Point and other military colleges as a classic textbook example of the effectiveness of airborne operations.

The capture of Fort Eben-Emael is renowned for a number of military firsts. It was the world’s first gliderborne attack, where specially trained glidermen were inserted into an enemy’s defensive position. It was the first time that hollow shape-charge explosives were used to breach steel and concrete fortifications that were considered impregnable. And the attack on Eben-Emael (and the adjacent Albert Canal bridges) also marked the first useof Hitler’s Blitzkrieg tactics. This bold action changed the way military strategists would prosecute war in the future, and it still heavily influences military planning today.

The Strategic Fort Eben-Emael

Why did Hitler choose to attack the most heavily armed fortress in all of Europe as his opening thrust in World War II? Fort Eben-Emael lay within 15 miles of the German border, south of the Dutch city of Maastricht, and adjacent to the Meuse River, the border between the Netherlands and Belgium. The fort was situated to cover the Vise Gap through which it was anticipated that German forces would pour when they began their invasion of the Netherlands and Belgium. It was also the portal to the Gembloux Gap that led to routes into central Belgium; if Eben-Emael fell, the heart of Belgium would be open to invasion.

Eben-Emael was the foremost central bastion in a large chain of 12 formidable and heavily manned Belgian fortresses interspersed with natural obstacles of marshlands, rivers, valleys, and mountains that ringed the city of Liège and protected the entry to the flatlands of central Belgium. This ring of fortresses was named Position Fortifiée de Liège.

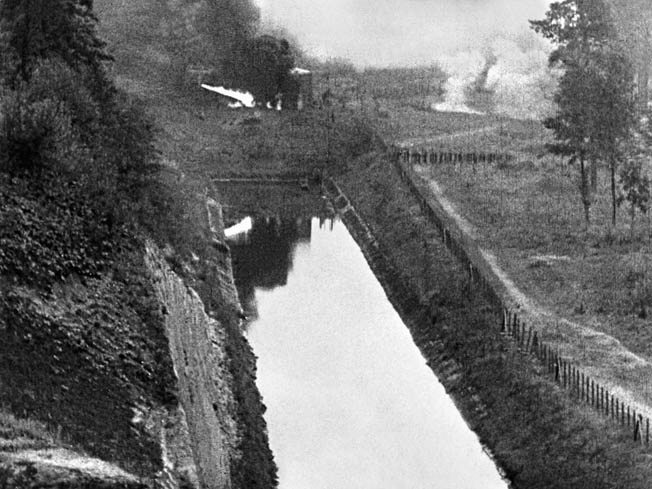

Fort Eben-Emael was designed to be the showstopper. Lying alongside the newly constructed 50-yard-wide Albert Canal, dug as a strategic defensive barrier, the fort had large gun casemates emplaced into the side of the canal. Their function was to lay covering fire up and down the canal to protect the three large steel bridges that a German army would have to cross to enter Belgium and the Netherlands.

The importance of these three bridges cannot be underestimated. Hitler’s divisions first needed to cross the Kanne, Vroenhoven, and Veldwezelt Bridges to enter Belgium. If Hitler’s advance forces could be stopped cold here, or so the thiking went, there would be enough time for the Belgian and the Dutch armies to prepare defensive positions farther inland, and the invasion would be held up long enough for the French and British armies to rush to the scene.

Thus, Eben-Emael’s strategic position was a linchpin in overcoming other defenses behind it. If Eben-Emael could not hold, Belgium and the Netherlands would be unable to contain an invasion, and their defenses would likely unravel, exposing the heart of Belgium.

The fort was built between 1932 and 1935 on Saint Peter’s Hill, a strong defensive position and natural overlook from which hostile military movement could be seen miles away. It was literally built into the hill at a cost of 50 million Belgian francs, a massive cost at the time for a small country like Belgium.

Eben-Emael’s design rendered it virtually unassailable by conventional ground forces; in fact, it was built to “deter an aggressor from the east from contemplating breaching Belgian neutrality.”

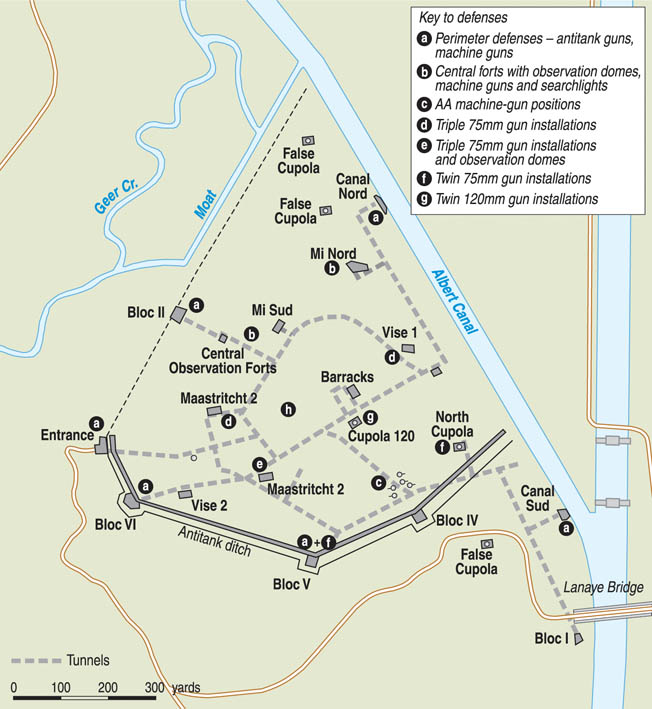

Shaped like an arrowhead or diamond, with the sharp point facing north, the fort measures 3,600 feet from north to south and 2,600 feet from east to west, and occupies an area the size of 70 football fields. The fort’s defenses took advantage of natural and engineered obstacles that would make it too costly to attack. The Albert Canal, running along its eastern edge, lined with near-vertical concrete sides more than 130 feet high, rendered assault from that quarter impossible. To the west, the fort was bordered by the Geer River and reinforced by an antitank ditch. To the south it was defended by a 30-foot-wide antitank ditch 20 feet deep.

A Fort of Immense Firepower

Fort Eben-Emael’s offensive and defensive capabilities and weaponry were awesome, even by today’s standards. To intimidate anyone contemplating attacking the fort, it boasted a total of 16 gun emplacements. The top of the fort, 120 feet higher than the entry blockhouse at the base, was dotted with seven fortified blockhouses armed with 60mm antitank cannon and machine guns, topped with small concrete observation domes.

Six other thick, concrete casemates were sprinkled around the top of the fortress, four of which were armed with triple 75mm guns with a range of seven miles. Two of these casemates were positioned to fire to the north where the Albert Canal and Maastricht were located, thus they were called the Maastricht casemates. Two casemates faced south toward the small town of Vise, and were named Vise 1 and Vise 2. These casemates covered the southern bridges across the Albert Canal and could also be used to fire on the other fortresses around Liège if they came under attack.

Three large, flying-saucer-shaped cupolas with 12-inch-thick, 360-degree rotating armored domes fitted with twin 75mm guns that could fire in all directions were also placed on top of the fortress. The domes could rise four feet above the casemate for better observation and firing elevation and then be retracted for reloading. Coupole Nord (Cu 120), the center cupola, had the largest guns in the fort—two 120mm guns positioned alongside each other for maximum firepower effect. Three false cupolas made of thin steel were emplaced around the fort’s perimeter to further confuse and deter potential attackers. Each casemate or cupola had electric elevators to provide ammunition to the gun emplacements.

Two blockhouses were sited on the banks of the Albert Canal to fire north and south to protect the bridges and were thus named Canal Nord and Canal Sud. Six outside artillery observation posts were linked to the fort, covering the most likely enemy approaches. Additionally, five large, heavily defended concrete blockhouses protected the south and east sides of the fort, with Bloc 1 being the fort’s main entrance. Gun crews consisted of 16 to 30 men, depending on the type and number of guns in the emplacement.

And, as if all of these positions were not formidable enough, two concrete machine-gun emplacements, Mi Nord and Mi Sud, were sited to cover the other gun emplacements on top of the fortress in the unlikely event that any enemy ground troops managed to penetrate the impressive exterior defenses.

Thus, the fort’s Offensive Battery comprised the north- and south-facing artillery casemates, while the three gun cupolas and the Defensive Battery consisted of the blockhouses and machine-gun emplacements, with four antiaircraft pits added on the south end of the fort for good measure.

Despite the impressive machine-gun and antiaircraft emplacements, the fort’s upper surface lacked fully developed belts of barbed wire, mines, and trenches to protect the casemates and cupolas from direct airborne attack simply because Belgian planners had never thought the idea of an airborne attack was feasible. The scarcity of antiaircraft emplacements indicates exactly how oblivious the planners were to such an eventuality. Airborne assault, whether by paratrooper or glider, had still not been fully conceptualized in 1940. Hitler ordered his airborne troops to train in absolute secrecy, lest the Belgians be warned of his plans.

Five miles of underground tunnels and galleries inside Saint Peter’s Hill were installed over the fortress’s two levels. Signs at intersections indicated which direction the soldiers should go to reach their defensive positions. Even today, when touring the fort, guides are very careful to keep the groups together so no one gets lost in the long passageways.

The Lower Level, accessed through Bloc 1, contained a decontamination room, defensive positions, armorers’ workshops, toilet and shower facilities, holding cells for recalcitrant Belgian soldiers, electrical generators, kitchens, storerooms, a commander’s office, barracks, an infirmary, and a pump room. The Intermediate Level consisted of three miles of tunnels that provided access to all fighting blocs, casemates, cupolas, and defensive blockhouses, plus a command post, telephone exchange, ammunition magazines, and ammunition hoists and stairs.

To ensure maximum security, the fort was designed with back-up defensive systems that could be brought into place if any of the cupolas or casemates were breached. A series of armored doors could seal off each gun emplacement if the emplacement was captured. The armored doors were arranged in twin pairs, with a space between that could be filled with sandbags and eight-inch steel beams in an emergency. These worked effectively when the German glidermen attacked, and the fort’s interior was never breached.

The Fort’s Garrison

The garrison’s normal complement of soldiers was 500, plus another 200 for command, technical, and administrative duties. However, in May 1940, many were sick from throat and respiratory irritations from their weeklong stints in the dusty tunnels. On May 9, 1940, the day before the attack, the gun battery strength was down by 100 men, as many conscripted soldiers, with war looming, were recruited away into the Belgian Army. Between sick soldiers, conscripts whose service had expired, and an additional 150 men away on leave, the garrison was 250 men below operational strength at this crucial time.

The total authorized garrison strength of 1,200 men, 233 of whom were stationed four miles away in the village of Wonck, meant that reinforcements would be late if the fort were to come under attack; the off-base soldiers would be summoned by the firing of 20 blank rounds from the fort’s big guns. By May 1940, morale was low due to repeated alerts and false alarms during the Phoney War, and the men were bored with garrison life. Training suffered, and equipment was not maintained for combat readiness. Furthermore, the Belgian troops were all artillery trained, versus infantry trained, which showed in combat when the Belgian soldiers were ordered to counterattack the Germans on top of the fort.

The complicated Belgian chain of command meant that fort commander Jean Jottrand could not directly order the guns to fire. They could only be fired on the command of the Belgian units in the surrounding area, and only at targets specified by them. This would prove to have dire consequences during the assault—for this lack of independent decision making and immediate reaction would enable the Germans to gain a foothold on the fort before the guns could fire.

While no single one of these mistakes would have resulted in the fall of the fort, the combined effect would cost valuable lives and time at critical moments during the attack.

The German Plan to Take Fort Eben-Emael

The airborne assault on Fort Eben-Emael was only one part of a complex airborne and ground attack plan. Hitler’s strategy called for three other glider parties to be launched at the same time as the Eben-Emael assault group.

These three groups were to take the three road bridges across the Albert Canal. Sturmgruppe Stahl (Assault Group Steel) was to capture the Veldwezelt Bridge, Sturmgruppe Breton (Concrete) would attack the Vroenhoven Bridge, and Sturmgruppe Eisen (Iron) was to capture the bridge at Kanne.

All bridges had been wired for demolition by the Belgians, so the assault groups had to land as close as possible to the target bridges in simultaneous surprise attacks before they could be defeated by the Belgian defenders. All of this while the fort was being neutralized by the fourth glider assault group—code-named Sturmgruppe Granit (Granite). It was the largest of the four groups, with 87 men assigned.

Altogether, 420 Fallschirmjäger and 42 glider pilots under the overall command of Captain Walter Koch were assigned these difficult tasks.

Junkers Ju-87 Stuka dive-bombers would be provided for close air support. Then paratroopers would land to provide support 40 minutes after the initial glider landings, followed by the 4th Panzer Division of the German Sixth Army that would provide artillery support as the troops approached the bridges from the border.

The key to successfully overcoming the fort’s defenses would be to knock out the fortifications within the first hour, while the Belgians were confused and disoriented. If this could not be done, the Belgians would have time to regroup and counterattack, hindering the Fallschirmjägers’ demolition of the guns. The pioneers (combat engineers or sappers) of Granit were divided into 11 sections, with one section in each glider. Each section was assigned a particular numbered target on the fort’s surface. Granit’s first priority was to destroy the antiaircraft guns, then the observation domes on top of the casemates. Then the Granit force would destroy the guns pointing north.

The German combat engineers would be relieved within 24 hours by pioneers of the 51st Battalion and 151st Infantry Regiment, who would attack the interior of the fort and force its surrender. Even today, many regard this complicated plan as too risky, yet Hitler’s Fallschirmjäger trained for it with great relish and confidence.

The Brandenburg Commandos

The Sturmgruppe Granit glidermen, under the direct command of 1st Lieutenant Rudolf Witzig, were essentially Germany’s first Special Forces, trained in firearms, night operations, parachuting, and survival training, with much emphasis placed on independent thinking and mental and physical resilience. They were even trained on how to drive Belgian trams. Because the battalion trained in Brandenburg, near Berlin, they were called the Brandenburgers. They were then moved to Czechoslovakia to practice on the Czechs’ fortified defense lines in the Sudetenland, then to Poland, and finally to two airfields near Cologne.

The Brandenburgers trained in complete secrecy for six months before the attack, completely cut off from the outside world. No mail, no visitors, no leave, and no contact with other German soldiers were permitted. Their parachute badges were removed from their uniforms. The place they were going to attack was never mentioned; they only learned the name of the fortress after they had captured it. Two paratroopers who were overheard making indiscrete comments about their mission were court-martialed and sentenced to death within hours, although the sentences were commuted the day after the assault took place.

Highly trained sport glider pilots were recruited for the assault, although many at first refused the opportunity to take part in this attack; they were expected to become infantrymen after the landing and participate in the fighting. Reluctant pilots were eventually persuaded to take part in this great adventure by appealing to their patriotism “for the Führer,” and were given the same pioneer training as the Brandenburgers.

Hitler, who had conceived of this complex assault, had another secret weapon up his sleeve. His engineers had recently invented a new type of explosive, the hollow-charge weapon—without which the attack could not have been attempted. By shaping conventional explosives around a copper cone, the detonation produced a plasma jet of molten metal that could penetrate nearly 10 inches of steel and even go through almost 14 inches of concrete—perfect for the bunker busting at Fort Eben-Emael.

The shaped charges came in two sizes. The largest charge, weighing 110 pounds, was in two sections and had to be hand placed on the bunker. Then a fuse had to be lit while the soldiers took cover. The smaller charge could penetrate from 4.75 to 6 inches of steel. The paratroopers trained to carry the explosive charges by carrying heavy rocks around, making their fellow soldiers think they were military prisoners.

Ironically, a Swiss scientist had invented a similar explosive for the French military, and the French officially approved it on May 10, 1940, the day the shaped charge was used by the Germans on Eben-Emael.

The DFS 230 glider was based on the design for a meteorological aircraft, with a short airframe and stubby 72-foot wingspan. With a framework of steel tubing covered by painted canvas fabric, the DFS could carry eight troopers, a pilot, and several hundred pounds of ammunition, for a total payload of 4,600 pounds. It was towed by a Junkers 52 transport plane and, once released from the tow plane, could glide 12 miles and land accurately on a pinpoint target. Its undercarriage was a skid attached below the fuselage.

Two full dress rehearsals of the glider assault on Eben-Emael were made, but it was found that the gliders could not stop on top of the fort; they would have slid right across the top and over the edge. To address this, a wooden saw-toothed drag brake was installed under the glider to dig into the ground. Hannah Reitsch, Hitler’s famous test pilot, personally tested the glider braking system and found it to be operational.

As the date for the operation drew near, the gliders were disassembled and loaded into furniture trucks, then transported to the Cologne airfields under heavy security and along empty roads at night. The airfields were surrounded by barbed wire and hidden from the view of other German troops by straw mats that were hung around them.

At midnight on May 9 the German High Command, Oberkommando des Heeres (OKH), issued orders to start the invasion of Belgium. Captain Koch received the orders at 12:40 am, woke the men at 3 am, and ordered them to make final preparations. The Junkers aircrews and Luftwaffe ground crews arrived at the airfields to make last-minute preparations. The departure time was 4:30 am, calculated to have all four glider groups landing at 5:25 am on their various targets. All went smoothly; at 4:35 the last glider was off the ground.

The pilots flew along a path illuminated by a line of blue searchlight beams and bonfires 20 kilometers apart, directing them to the Dutch border, at 8,500 feet. Problems soon arose. The glider carrying commander Lieutenant Witzig was cast loose early, and another glider was freed by a near collision, depriving the Granit assault group of two gliders before they had even reached the fort. This was 20 percent of their strength and included their commanding officer. Nevertheless, once the plan had been activated, it could not be recalled, so the remaining planes continued.

A strong tail wind meant that the Junkers had to tow the gliders over the Dutch border, compromising the silent approach. The gliders were finally released at 5:10 and, after 15 minutes of gliding, approached Fort Eben-Emael.

Much earlier, the Dutch and Belgian armies had detected the sound of German armor moving along the border, and Eben-Emael’s commander, Major Jottrand, received an alert order at 12:32 am from Headquarters III Corps. The fort’s internal siren rang and the process of calling in key personnel by telephone began. Confirmation of the alert came at 4 am, when the Junkers were heard flying over Dutch airspace. Jottrand finally sounded the invasion alert. He ordered the Kanne Bridge and the lock at Lanaye to be demolished, and for the two temporary wooden barracks at the entrance to Bloc 1 to be razed to the ground to permit a full field of fire from the position.

Unfortunately, some of the gun crews sent to demolish the barracks were Jottrand’s experienced gunners, leaving inexperienced troops at the guns. These soldeirs did not know the procedures for summoning the rest of the troops at Wonck (firing 20 blank rounds). Further, firing pins from Coupole Sud had recently been removed and had not been replaced properly. Finally, an armorer replaced them and some warning blanks were fired at 3:25, but the muzzle flashes set fire to the camouflage netting, obscuring the firing periscope’s view. The warning shots were not completed, and many of the Belgian soldiers at Wonck ignored the summons.

At 5:15 am, Jottrand was informed of unidentified aircraft over Maastricht, so he put the four machine-gun and antiaircraft crews on high alert. By 5:25 the gliders were already skidding to a stop on top of the fort, and the machine-gun crews that had opened fire at close range could not zero in on the fast moving gliders. Two of the machine guns jammed. Gliders were landing simultaneously by the three bridges on the Albert Canal. Ten minutes later the German ground offensive began.

Taking Out Cupole Nord

The 71 German paratroopers fanned out as they landed and rapidly went about their business, now under command of Sergeant Helmut Wenzel. The machine-gun positions at the south end of the fort were captured immediately by Sergeant Erwin Haug’s section, the first glider team to land. The glider landed so close to one position that it tore a machine gun right out of the pit and stopped beside another pit. Sergeant Karl-Heinz Lange led a brief charge on the pit and threw a stick grenade into it, killing one Belgian and enabling the Germans to capture two others.

Sergeant Karl Unger’s section landed within 30 meters of its target, Coupole Nord, and was joined by Haug’s section. Privates Hannes Else and Herbert Plietz dashed toward the objective. Inside the cupola, the Belgians had discovered that they did not have any canister rounds ready to sweep the top of the fort. Had they been available, these rounds may well have tilted the odds in favor of the defenders. Else detonated a 110-pound charge outside the infantry exit doors, killing and wounding several Belgian soldiers inside. On top of Coupole Nord, two German glidermen had detonated one of the new 26-pound shaped charges, making an impressive explosion that shook the ground around the cupola. The blast twisted the guns, damaged the ammunition mechanism, and cut the cables to the control system. Coupole Nord was put out of action. The surviving Belgian soldiers retreated down the stairs and prepared the barricade of steel beams and sand bags.

Sergeant Hans Nidermeier and his section quickly attacked the Maastricht 2 casemate after their glider landed heavily in the open ground between Maastricht 2 and Coupole 120. The two observers in the small observation post atop Maastricht 2 had not seen the gliders landing, but they knew something was up when they saw legs in German uniform on top of their casemate. A Belgian sergeant barely had time to warn the gun crews below when a charge went off atop the post, killing the men inside and causing splinters to fly in all directions.

A second charge was placed below a gun port, throwing the 75mm gun off its mountings, killing two Belgians and wounding one, and opening a two-foot square hole through which the glidermen scrambled after throwing hand grenades. Some Belgians lay stunned from the blasts, but the remainder scrambled down the stairs to the intermediate level where they packed steel beams and sandbags into the security door.

Sergeant Peter Arent’s section attacked Maastricht 1 after landing only 80 feet from it. They placed a shaped charge against one of the gun embrasures and blew one of the 75mm guns off its mounting. The Belgians retreated down to the intermediate level and prepared to counterattack, but Arent dropped a bundle of hand grenades down the elevator, forcing the Belgians to seal off the lower entrance with the steel beams and sand bags.

After landing only 55 yards from Mi Sud, Sergeant Ewald Neuhaus found it empty because its gun crew was still back at Bloc 1 clearing the administration offices and tearing down the wooden barracks. However, Belgian machine gunners soon arrived and opened fire on the attackers. Sergeant Ernst Schlosser discharged a flamethrower against the embrasure, silencing the guns, and soon two 27-pound and three 110-pound hollow charges detonated in the southern embrasure, causing the shaken Belgians to withdraw to the intermediate level below.

Kurt Engelmann’s section assaulted Mi Nord in a similar manner. They attacked with flamethrowers, a 2.2-pound charge, a 27-pound charge and a 110-pound charge, blowing a hole through its walls through which they attacked. Several dead Belgian soldiers lay about. The field telephone rang, and Engelmann calmly answered it. He listened to some rapid-fire French then said, “Here are the Germans,” to which the Belgian officer replied, “Oh, Mon Dieu.” Mi Nord was to become the German command post for the rest of the assault.

By 6:30 am, Lieutenant Witzig, whose glider had been cast loose from the tow plane too early, had commandeered another glider and Junker tow plane, landed on the fort and resumed command. His immediate problem was Coupole 120, which was still rotating although its guns could not fire because its periscope had not been attached to the cupola and the ammunition hoists and loaders were not working. However, the soldiers within were firing their rifles at the attacking Germans.

At 6:45, Witzig ordered another attack on Coupole 120; the Germans advanced, sheltering behind Belgian prisoners, and attached a 121-pound hollow charge above the left-hand gun. Although the charge did not penetrate, the cupola stopped turning. So the Germans moved on, thinking the cupola was out of action, and attacked Bloc 2. However, the Belgians reoccupied Coupole 120, wearing gas masks to protect themselves against the poisoned atmosphere, and continued shooting at the Germans. Later, one of Haug’s men, Sergeant Ernst Grechza, roaring drunk from rum in his water bottle, climbed up Coupole 120 and sat astride the gun, riding it like a bronco. Furious, Wenzel ordered the soldier down and placed some charges into the gun barrels.

Within 20 minutes the glidermen had successfully attacked nine of the Belgian positions. Charges were placed on seven armored observation domes, with five domes rendered inoperable. Nine of the 75mm guns in three of the casemates were destroyed. Most of the other casemates and emplacements fell like dominoes. Thus, the main gun emplacements that could have seriously hindered the Albert Canal attacks, with one exception, had been cleared by only 71 men. Coupole Sud was the only gun atop the fort that remained operational, firing on targets aimed by the Bloc 1 observation posts. All German attempts to destroy these positions failed, including attacks by Stuka dive-bombers.

As the day wore on, things got hot for the Germans as the Belgian army recovered from the initial shock of the attacks. There were two half-hearted counterattacks by the Belgians within the fort, but these soldiers were artillery trained and did not know how to prosecute a ground attack.

The exhausted and thirsty Germans had not been relieved according to the timetable. An effort to cross the Albert Canal on the evening of May 10 to relieve Sturmgruppe Granit on Eben-Emael was stopped by Blockhouse Nord’s 75mm guns.

At the fort, Witzig’s assault group was running low on ammunition and water. To make matters worse, the other Belgian fortresses within range of Eben-Emael began directing their fire onto its upper surface to dislodge the Germans, lobbing 1,200 shells onto the position. Several Germans were wounded, but most of them safely sheltered in the gun emplacements they had captured.

After dark the Germans renewed their attacks on several operational gun emplacements. Descending into Maastricht 1, they found the armored doors blocking their way. They went up to the surface and returned with a 110-pound hollow charge with which they blew in the armored doors, killing four Belgian soldiers, but could go no farther into the fortress because of the debris.

Meanwhile, two bridgeheads over the Albert Canal had been taken intact, with the third, the Kanne Bridge, destroyed by the Belgians. Just 40 minutes after the glider landings, paratroopers reinforced the glidermen, and eventually Belgian resistance was overcome.

The Fall of Fort Eben-Emael

At 4 the next morning, Pioneer Battalion 51 managed to cross the Albert Canal to subdue Bloc II by firing a flamethrower through the aperture and exploding a 110-pound charge against the embrasure, killing one Belgian gunner and wounding six more. By 7 am, the Germans were climbing the slope of the fort and linking up with Witzig’s group, and at 8:30 Witzig turned the captured installations over to them.

Still, some defenders were holding out. By mid-morning, the air inside the fort was deteriorating as poisonous fumes from the explosions spread through the ventilation system, and Belgian morale was falling. Major Jottrand planned the surrender, and at 11:45 a Belgian bugler, Vervier, and an officer, Captain Vamecq, stepped outside Bloc 1, walked across the retractable bridge across the moat and, with a white sheet flying on a broom handle, negotiated the surrender of the fort.

The firing ceased, but no one had pulled the bridge back, and suddenly the entire garrison of 780 men came out with their hands in the air behind a perplexed Vamecq; the line of despondent Belgian prisoners was one mile long. The garrison had suffered 21 killed and 145 wounded. The survivors were transported to Dortmund and Hemer and kept in strict isolation until July 4, 1940, because the Germans did not want knowledge of their glider attack or their secret hollow-charge weapons to reach the Allies. Finally, they were imprisoned in a POW camp at Fallingbostel, near Hannover, Germany.

The fall of Eben-Emael demonstrated how a fast, hard-hitting, surprise attack could shock defenders, causing morale to plummet rapidly, leading to surrender. Through excellent planning, innovative use of gliders, and hollow-charge technology Eben-Emael fell in just over 31 hours. Sturmgruppe Granit suffered six killed and 15 wounded. All officers of the glider assaults received the Knight’s Cross, and the NCOs and men of Sturmabteilung Koch, the parent regiment, received a generous allowance of Iron Crosses, personally presented by Hitler in a special ceremony on May 15, 1940.

The daring assault on Fort Eben-Emael paved the way for rapid German victory in the West. Within weeks, Hitler’s army marched into Paris.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments