By Arnold Blumberg

Despite costing the Union Army 55,000 men in five weeks of hard marching and grueling combat, Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s Overland Campaign of 1864 still had not accomplished its goal of defeating Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. By early June, Lee’s legions, although reduced by another 33,000 casualties, remained close to Richmond’s fortifications and the nearby swamplands of the Chickahominy River. There was no favorable ground upon which Grant could maneuver his larger army to advantageously fight. Reluctantly, he realized that he needed to review his options if he was to destroy his determined opponents.

Grant’s new plan called for sending cavalry west toward Charlottesville to cut the Virginia Central Railroad, then shifting the Army of the Potomac south and west, severing the rest of Lee’s supply lines and isolating the Confederate forces at Richmond. For the scheme to succeed, Grant had to steal another march on Lee. Once this was done, the ensuing military action would become a siege, which both Grant and Lee understood would eventually spell the Confederacy’s doom.

Grant initiated his new strategy by preparing to march the Army of the Potomac to the south bank of the James River. This maneuver would place him within striking distance of the city of Petersburg, 23 miles south of Richmond, which served as the rail center and supply transit point for much of the material for Lee’s army from the Deep South. On June 5, Grant wired Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck in Washington. Once he passed south of the James River, Grant said, “I can cut off all sources of supply to the enemy except what is furnished by the [James River] canal.” If Maj. Gen. David Hunter, Union commander of the Department of West Virginia, could capture Lynchburg, the use of the vital James River Canal would be lost to the Confederacy. If Hunter did not succeed, Grant observed, “I will make the effort of destroying the canal by sending cavalry up the south side of the [James] river.”

Grant’s plan demanded strict secrecy. He had to slip away so stealthily that Lee would not realize the absence of the Federals until they were storming the gates of Petersburg. In the meantime, some sort of adjunct operation had to be embarked upon to sever Lee’s vital supply line to Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley, which provided the Army of Northern Virginia with a majority of its foodstuffs, finished goods, and other necessities.

Sheridan’s Raid

On June 6, Grant ordered Hunter to move to Charlottesville and destroy as much of the Virginia Central Railroad as possible as he moved eastward. Hunter was then directed to link up with a mounted force under Maj. Gen. Phil Sheridan at Charlottesville. After he and Sheridan had completed their work destroying rail lines and canals, Hunter was to proceed east and join the Army of the Potomac.

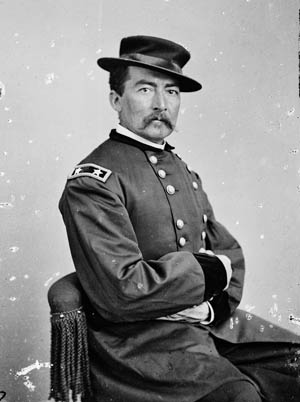

Sheridan had gained much of his battlefield experience as an infantry division leader at Perryville, Murfreesboro, Chickamauga, and Chattanooga, but he retained a firm grasp of cavalry tactics and organization from his brief service as a cavalry colonel in Mississippi earlier in the war. These traits had attracted Grant’s attention, and Sheridan seemed the perfect candidate to whip the Army of the Potomac’s cavalry branch into a more aggressive fighting force than it heretofore had been. As a result, when Grant came east to take command of all the United States armies, he brought Sheridan with him. Sheridan quickly justified Grant’s faith in him by retooling the eastern cavalry through intensive training, reequipping, and assigning competent new commanders to ensure maximum fighting capacity.

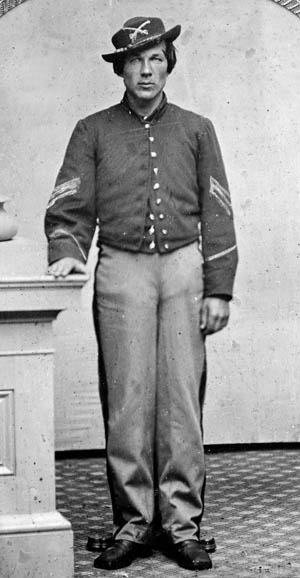

With full confidence in Sheridan’s ability to operate independently and achieve the desired results the mission called for, Grant directed him to commence his raid on June 7. Sheridan took two of his three cavalry divisions on the raid. One was the 1st Division under Brig. Gen. Alfred T.A. Torbert, which contained three brigades under Brig. Gen. George A. Custer, Colonel Thomas C. Devin, and Brig. Gen. Wesley Merritt.

The 2nd Cavalry Division was also slated to take part in the operation. It was headed by Brig. Gen. David M. Gregg, like Torbert a West Point graduate. Modest, firm, and fearless in combat, Gregg was hailed as the finest type of cavalry leader. The 2nd Division included two brigades: the 1st under Brig. Gen. Henry E. Davies, and the 2nd led by Colonel John I. Gregg. Neither officer was a professional soldier, but each had proved his mettle under fire.

The 3rd Cavalry Division, led by Brig. Gen. James H. Wilson, remained with the Army of the Potomac to act as its eyes and ears. Along with the 1st and 2nd Divisions, four batteries of horse artillery under Captain James M. Robertson accompanied Sheridan’s expedition. A total of 9,300 men and 20 cannons made up his strike force. A wagon train comprising 125 ambulances and wagons hauling bridge-building equipment completed the expedition.

The Attrition of Sheridan’s Cavalry

The units spent the better part of a day moving from their camps along the Chickahominy River 12 miles east of Richmond to the Pamunkey, a tributary of the York River located east of the Chickahominy. Before they departed for the new rendezvous point, the Federal troopers were issued three days’ rations, two days’ grain for their horses, and 100 rounds of ammunition.

It was apparent to the troopers from the detailed preparations that a big event was about to occur. Veteran bugler Carlos McDonald of the 6th Ohio Cavalry observed that the preparations meant “we are to have some long marches away from our base of supplies, and in all probability some fighting.” Such speculation aside, few officers or enlisted men foresaw a major cavalry raid in the offing. As one member of the 9th New York Volunteer Cavalry Regiment observed, “Much reticence was observed by the officers since Grant had taken command, and only division commanders were informed of contemplated movements before their execution. To the men and subordinate officers this move was an enigma.”

On Tuesday, June 7, the sun rose at 4:45 am on what would be a rather humid day, even though the temperature would not exceed 74 degrees. Fifteen minutes after daylight, the Union cavalry camps echoed with the bugle call “Boots and Saddles,” followed by “To Horse.” Within the hour an eight-mile-long column of Federal horsemen—Gregg’s division followed by Torbert’s—traveling at a pace of four miles an hour, filled the road heading northwest along the south bank of the Mattapony River. After a march of only 15 miles, the column halted and bivouacked for the night.

A major cause for concern on the first day was the alarming number of horses that broke down only hours after the raid began. The slow pace of the Union riders was calculated to prevent excessive horse wastage on the march. Such losses would greatly impair the force’s mobility and striking power when it came time to confront the enemy. Unfortunately for Sheridan and his troopers, the expedition would continue to lose horseflesh at an ever more quickening rate as their advance continued. The animals that could not keep up with the march were shot and left by the roadside, their riders tramping through the countryside looking for new mounts to avoid joining the growing number of dismounted.

The next day the pace of the Federal expedition picked up with a respectable 25-mile march reaching Pole Cat Station on the Richmond, Fredericksburg and Potomac Railroad in the late afternoon. While most of the brigades went into camp or foraged the area, Merritt’s reserve brigade was tasked with tearing up the nearby rail line.

Wade Hampton of the Confederate Cavalry Corps

As the Union marauders splashed across the Pamunkey on June 7, they were shadowed by Confederate scouts who hovered around the blue column, watching and exchanging sporadic gunfire as the Federals marched on. Reports of the Union move reached Maj. Gen. Wade Hampton, commanding the Confederate 1st Cavalry Division, early on the morning of June 8 at his Atlee’s Station headquarters near Cold Harbor. Hampton immediately sent a report of Sheridan’s activities to Lee, who ordered him to counter any threat Sheridan’s riders posed. Hampton would prove to be more than up to the challenge.

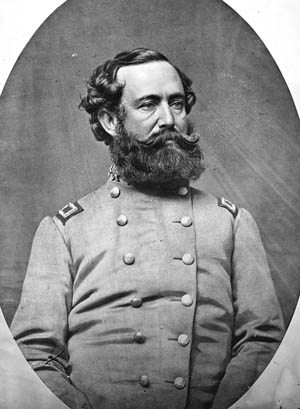

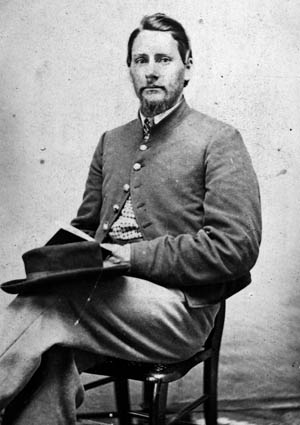

Reputed to be the richest man in the South on the eve of the Civil War, Hampton was an avid outdoorsman and an expert horseman. The handsome, brown-haired, gray-eyed South Carolina aristocrat did not smoke and only sparingly drank alcohol. At the start of the war, he raised troops for the Confederacy and saw action as an infantry colonel at the First Battle of Manassas, where he received the first of several wounds he would suffer during the war. The next year he transferred to the cavalry and became a brigadier general under the fabled Maj. Gen. James Ewell Brown Stuart, commander of Lee’s cavalry arm. Hampton subsequently fought in all the major battles of the Army of Northern Virginia before being badly wounded at Gettysburg.

After returning to active duty in early 1864, Hampton assumed command of one of the three cavalry divisions that comprised the newly reconstituted Cavalry Corps. After Stuart was mortally at Yellow Tavern in May 1864, Lee was unable to choose his successor. Both Hampton and Fitzhugh Lee, the general’s nephew, reported directly to the army commander for instructions. This unsatisfactory chain of command situation was still in place when Sheridan’s new sortie got underway.

By the opening of the 1864 campaign, Union horse soldiers were more numerous, better mounted, and better armed than their Confederate counterparts. Hampton realized that to charge such a superior force on horseback was seldom feasible. His alternative was to fight dismounted. One subordinate described Hampton’s fighting method: “He could dash his forces, mounted, to favorable points with great celerity, dismount and rush in, and if advisable, draw them out as quickly and hurl them fiercely on some other weaker position.” Hampton always brought the maximum force possible to the point of attack or defense, turning his men into good, hard-fighting infantry and at the same time preserving their good qualities as cavalry. Although his soldiers’ rate of fire using muzzle-loading weapons was slower, it was more accurate and longer-ranged, and therefore caused more damage to the enemy. The impact of his careful style of generalship gave the men serving under him unwavering confidence, and the disorganized stampedes so common under Stuart were unknown under Hampton.

Hampton’s 1st Brigade was led by Colonel Gilbert J. Wright. An attorney by profession, Wright was a wounded combat veteran of the Mexican War. He possessed great courage and dogged determination and proved to be a fine combat leader. Second Brigade was commanded by Brig. Gen. Thomas Rosser, a member of the West Point Class of 1861. He had been an officer in the Confederate cavalry since 1862 and was esteemed as a good fighter. Brig. Gen. Matthew C. Butler handled Hampton’s 3rd Brigade. Butler was known for his courage and calmness in the midst of combat, the sort of leader who sat on his horse quietly watching while shots and shells exploded around him. Butler had lost his right foot a year earlier at the Battle of Brandy Station, but this did nothing to diminish his performance as a cavalry officer.

Fitzhugh Lee was a graduate of the West Point Class of 1856 and had fought in the Regular Army against the Plains Indians prior to the Civil War. The nephew of Robert E. Lee, Fitz Lee was a competent leader of mounted forces whose service during the war swung between brilliant and lackluster. His division included the 1st Brigade under Brig. Gen. Williams C. Wickham, a Virginian lawyer, politician, and planter. Wickham was ably assisted by his senior colonel, Thomas Munford, a graduate of the Virginia Military Academy. Brig. Gen. Lunsford L. Lomax commanded the 2nd Brigade. Lomax had attended West Point and served on the frontier before the Civil War; he was deemed a steady and competent officer. Colonel Bradley T. Johnson’s 1st Maryland Cavalry Battalion, along with the Baltimore Light Artillery Company, an independent command, were attached to Lomax’s unit. For artillery support, Hampton had the services of Major Robert P. Chew’s four-battery Horse Artillery Battalion. In all, Hampton commanded 6,400 men and 14 cannons.

In Hot Pursuit of Sheridan

Anticipating that the enemy’s targets were the rail hubs and supply depots at Gordonsville and Charlottesville, Hampton set his division in motion on June 9, intending to get between Sheridan and his goals. He directed Fitz Lee to follow as soon as possible. Most of the Southern riders had no idea what sort of mission Hampton had embarked on, but Sergeant George M. Neese of Chew’s Horse Artillery Battery spoke for many when he wrote in his diary: “General Hampton with a good force of cavalry is after the raiders in hot pursuit, and when he strikes a warm trail there is usually some blood left in the track and some game bagged.”

Moving at a steady walk with hardly any stops, Hampton’s force covered 30 miles the first day. Meanwhile, Sheridan, unaware he was being pursued, covered 24 miles along the route of the Virginia Central Railroad north of the North Anna River, leaving a trail of dead horses in his wake. As the blue column moved on, its rearguard and detached foraging parties were constantly harassed by Rebel scouts.

On the 10th the chase continued with Hampton’s horsemen reaching Fredericks Hall Station. Lee’s troopers followed a few miles behind. By 3 pm the Southerners went into camp at Louisa Court House on the Virginia Central Railroad, just south of the North Anna River. Rosser’s brigade settled in several miles west of Louisa astride the railroad and the direct route to Gordonsville. Wright’s and Butler’s commands were just east of Trevilian Station, Fitz Lee’s division a half mile from Louisa on the Virginia Central. Hampton had accomplished his first objective of interposing himself between the enemy and Gordonsville, but it had cost his command a large number of horses. This translated into a significant number of men who would not be present for battle in the coming days. In addition, a tactical problem remained for Hampton: a four-mile gap between his and Lee’s position, with the Marquis Road running through the gap from Carpenter’s Ford on the North Anna River to Louisa Court House.

As the Confederates closed on Louisa Court House, the Federals crossed to the south bank of the North Anna at Carpenter’s Ford, six miles northeast of Louisa. By the end of the hot day, they went into camp. Merritt was six miles north of Trevilian Station, Devin five miles northeast, and Custer four miles north of Louisa. Gregg’s division was still marching and strung out along the roads from Carpenter’s Ford. The Union column had lost another 500 horses. As darkness covered his command, Sheridan was unaware that Hampton was in his front and that Lee held Louisa Court House.

The Battle Begins at Fredericksburg Road

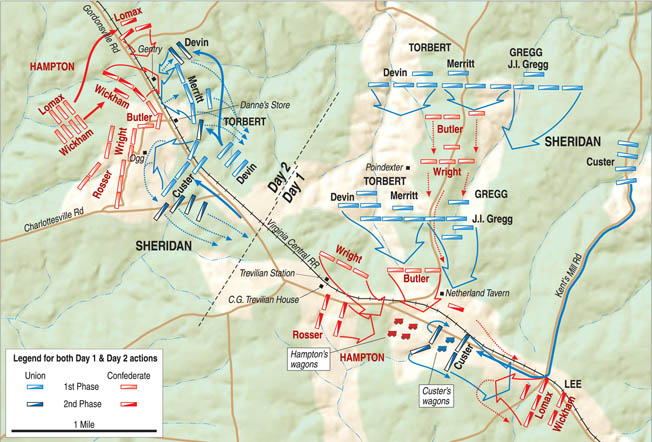

Sheridan intended to capture Trevilian Station the next day, cutting the Virginia Central and the Lynchburg branch of the Charlottesville rail line. Hampton planned to launch an assault in the morning, using his division to drive the Federals frontally while Lee flanked them. The result would leave Sheridan pinned against the North Anna River and exposed to utter destruction.

As events unfolded, neither scheme would see fruition, primarily because the terrain around Trevilian Station was not suited for mounted combat. Not only was the station located between two creeks, but the surrounding countryside was filled with farmsteads, rolling hills, ridges, thick undergrowth, and woodlands, all of which greatly impeded horse and foot movement. The main thoroughfare in the area, the Louisa Court House-Gordonsville Road, was an unimproved avenue winding along the Virginia Central Railway and crossing the tracks at 12 different locations between Louisa and Gordonsville.

At 5 am on June 11, Merritt’s reserve brigade, led by the 2nd U.S. Cavalry Regiment, passed Bibbs Crossroads then turned south on the Fredericksburg Road, heading toward the Virginia Central. Trevilian Station was a mile or so distant. Torbert rode with the Regulars. Confederate pickets were encountered and driven in. Hearing the news, Hampton, who had just come up from his headquarters at the Netherland Tavern, hastily deployed Butler’s South Carolina Brigade. Arranged from left to right were the 4th, 5th, and 6th South Carolina Cavalry regiments across the Fredericksburg Road just below the crossroads. Meanwhile, Merritt sent the 2nd U.S. Regiment ahead to capture Trevilian Station. Butler’s command immediately charged the Federals, who in turn countercharged the Rebels and held them in check.

Reacting to the clash on Fredericksburg Road, Hampton ordered Butler to attack again and directed Wright to act as reserve and guard the latter’s flanks. Earlier that morning Hampton had sent Fitz Lee instructions to move up the Marquis Road east of the Fredericksburg Road and head north to Clayton’s Store and the North Anna River. Rosser, five miles west of Trevilian Station, was ordered to protect the western flank against the appearance of Hunter’s army and act as the cavalry’s reserve.

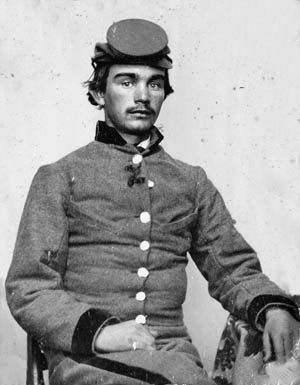

Butler shouted to his men, “Dismount to fight, action left and action right!” A lawyer before the war, the 27-year-old Butler led a brigade whose members, about 1,000 strong, carried muzzle-loading Enfield rifles and functioned more like mounted infantry than traditional cavalry. Ordered forward, the South Carolinians drove the 2nd U.S. back three-quarters of a mile, with the fighting becoming hand to hand. Part of the 4th South Carolina Regiment almost gave way during the fight, but Butler managed to rally the men and sent them forward once again.

Retreat to Trevilian Station

As Butler contended with the 2nd U.S., Merritt formed the rest of his brigade in thick brush close to the enemy. The 1st New York Dragoons were placed on the right, followed by the 6th Pennsylvania and 2nd U.S. in the center, and the 1st U.S. Cavalry on the left. Merritt’s 5th U.S. Cavalry and Lieutenant Edward Williston’s artillery battery were posted in the rear of the Federal line. A crisp firefight soon developed, followed by the entire Union line advancing on foot and driving back the Confederates. Colonel B. Huger Rutledge, commanding the 4th Carolina Cavalry, sent an urgent appeal to Butler for help, saying his regiment was being out-flanked. Butler quipped that the colonel should “flank back,” then asked Hampton for reinforcements. Hampton ordered Wright’s brigade and a section of Captain James Hart’s South Carolina Horse Artillery Battery to support Butler’s men.

As Wright’s unit arrived on the field, Butler placed it on the left of his line in a patch of heavy undergrowth. Wright’s four regiments and one battalion dismounted and fought on foot. Aided by the effective fire from the Confederate horse artillery batteries perched atop a hill, Wright’s force made an immediate impact on the battle. Hampton later reported that Butler and Wright had “pushed the enemy steadily back and I hoped to affect a junction with Lee’s division at Clayton’s Store in a short time.”

Responding to the setback, Torbert committed Devin’s brigade to the fight. After connecting with Merritt’s left and right flanks, Devin was told that a general assault would take place as soon as J. Irvin Gregg’s brigade of David M. Gregg’s division arrived on the battlefield. The fighting intensified while Torbert waited for Gregg. Butler reported that his and Wright’s men “were thus struggling with a superior force in my front, and the stubborn fight [was] kept up at close quarters for several hours.”

Growing increasingly impatient with the existing stalemate, Sheridan, patrolling the Union front, sent the 220 troopers of the 9th New York Cavalry, Devin’s brigade, in a charge through the enemy lines toward the Poindexter House, located on the west side of the Fredericksburg Road a mile north of Trevilian Station. Although their colonel was mortally wounded along with 40 others in the charge, the New Yorkers, joined by some of the Regulars and the 4th New York Cavalry, managed to force back the Confederates, who retreated from their wooded position. The grayclad riders were driven almost to Trevilian Station, a distance of nearly two miles, losing 380 prisoners in the process.

Butler’s and Wright’s retreat for the most part was an orderly one, and they took up a position along a fence and poured concentrated rifle fire at the approaching foe, even mounting a few futile counterattacks. At 9:30 am, Gregg’s brigade came up on Devin’s left, bringing a new artillery battery with it. Continuing to fight his men as infantry, since the undergrowth and wooded areas made mounted combat impractical, Torbert drove the defenders south of Trevilian Station before stopping his pursuit.

Custer Strikes Hampton’s Wagon Train

At noon a lull fell across the battlefield. Although satisfied with the battle’s progress so far, Torbert was concerned about the whereabouts of his third brigade, commanded by Custer. Earlier in the day the 1st Division leader had ordered Custer to march on Trevilian Station by way of Nunn’s Creek Road, an avenue that ran parallel to and between the Marquis Road and the Fredericksburg Road, about 1½ miles distant, and outflank any enemy at the station. Torbert had received no word from Custer, and he was worried about his lost brigade. As it turned out, his fears were well founded.

At 5 am, Custer’s Michigan Brigade had commenced its march down Nunn’s Creek Road to Trevilian Station. Not long after, elements of the 7th Michigan Cavalry, reinforced by the 1st Michigan Cavalry, were attacked along the Marquis Road by Wickham’s brigade. After an hour of skirmishing, the Virginians withdrew to Louisa Court House. Custer resumed his march at 6 am. The blue column snaked its way south to the Gordonsville Road, which ran through Trevilian Station 1½ miles to the west.

Around 8 am, Hampton’s wagon train was sighted east of the station. A charge by the 5th Michigan Cavalry soon bagged the caravan, netting several hundred prisoners, 1,500 horses, and 50 wagons. Alerted by the commotion in his rear, Butler hurried some of his men, along with the 7th and 20th Georgia, back to Trevilian to cut off the 5th Michigan. At the same time, Custer sent the 6th Michigan to support the 5th. A squadron of the former charged and broke the 7th Georgia, which fell back to protect the Confederate wagon train. Custer then ordered the 6th Michigan to guard the Gordonsville Road near the intersection with Nunn’s Road.

Custer Encircled

Learning that the Federals were behind him, Hampton directed Rosser’s brigade and regiments from Butler’s and Wright’s commands to form a defensive barrier near Netherland Tavern. Custer had driven a wedge between Hampton’s and Lee’s divisions, and even after the latter sent word to Lee to hurry and join him Lee took an unaccountably long time to comply.

Quicker to come to Hampton’s aid was Rosser, who led his Laurel Brigade east. Chew, alerted by Hampton to the seriousness of the situation, rushed six cannons to a hill overlooking Trevilian Station and began shooting at Custer’s Wolverines. From the north the Jeff Davis Mississippi Legion, in Wright’s brigade, pitched into Custer’s men, routing one regiment with a mounted saber charge. The Mississippians, in turn, were forced to retreat when attacked by another Federal unit.

Rosser’s men struck Custer’s command in the flank, driving it back in confusion and capturing many members from the 5th Michigan while almost colliding with Wright’s troopers. As his men ran east along the Gordonsville Road, Custer joined his attached artillery battery just going into position near the rail line. Soon he and the guns were surrounded by dismounted Rebels. The Union general broke through the attackers, rallied portions of his command, and escorted the threatened cannons to safety. Custer formed a new battle line supported by the artillery a mile east of Trevilian Station at the Gordonsville-Nunn’s Creek Road intersection. While Custer was forming his defensive position, one of his officers mistakenly led the captured Rebel wagons back into the Confederate lines.

Custer had no time to stew over the loss of the wagon train—Fitz Lee’s cavaliers were finally entering the battle area. Their appearance hemmed in the Michigan Brigade on three sides. The 15th Virginia, Lomax’s brigade, wasted no time in attacking the Wolverines in the flank, scattering the 1st Michigan Cavalry with sabers and pistols and seizing five Union artillery caissons and Custer’s headquarters wagon, as well as three of his personal horses. The fighting grew heavier as more of Lomax’s regiments joined the fray and Lee’s men connected with Hampton’s flank. Custer’s command was surrounded and fighting on every front.

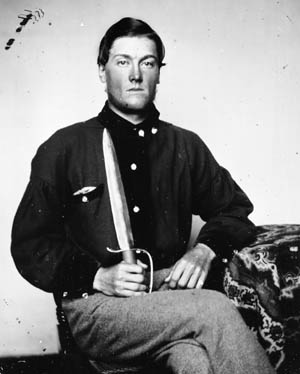

Following Lomax down the Louisa Court House Road, Wickham’s men eagerly engaged the encircled Michiganders. Custer was seemingly everywhere, rallying his men and even leading two frontal attacks to recapture a lost artillery piece. During three hours of desperate combat, Custer lost 11 killed, 51 wounded and 299 captured from his command of fewer than 1,000 men. In addition, he was hit in the arm and shoulder by spent bullets.

Hampton Orders a General Retreat

Around noon, Hampton, fearing a renewed attack from Torbert, withdrew Butler and Wright from the enemy front and placed them on a low ridge west of the railroad. The Confederate pressure on Custer continued. At about the same time, Torbert learned of Custer’s critical situation from one of his staff officers, who was able to pierce the Southern cordon surrounding the Michigan Brigade.

Determined to save Custer and his command, Merritt charged without orders into the Southern troopers surrounding Custer, scattering the enemy and relieving the pressure on Custer. Sheridan quickly directed Torbert to strike Butler’s and Wright’s new line with Merritt’s, Devin’s, and Gregg’s brigades. The renewed attack on Butler forced him back to a new position Hampton was forming around Trevilian Station. With great skill and calm, Butler put his units and those of Wright and Rosser into a defensive stance on a low rise near the station, where they drove off another attack by Custer.

The Confederate situation deteriorated after repeated Union assaults created gaps between Butler and Wright and drove Fitz Lee’s troops back toward Louisa Court House. Irvin Gregg’s brigade appeared then and delivered a decisive blow. At 3 pm, the 10th New York Cavalry, part of Davies’ command but attached to Irvin Gregg’s brigade, entered the attack. The 4th and 16th Pennsylvania Cavalry, supported by artillery, cleared the area around Netherland Tavern of a Confederate artillery battery and dismounted troopers.

At Trevilian Station, the 1st New Jersey Cavalry routed Wright’s brigade. To the east, Custer faced Lee’s division but did not attack due to the heavy fire coming from Lee’s superior numbers. To the west of Trevilian Station, Rosser was heavily engaged, holding his own but slowly being encircled. Rosser was wounded by a bullet below the knee and evacuated from the field. Not long after, yielding to the incessant pressure from his antagonists, Hampton ordered a general retreat several miles to a point along the Gordonsville Road but still blocking Sheridan’s route to Gordonsville and its vital rail center. Lee’s division fell back toward Louisa Court House. During the day’s fighting, 699 Union soldiers were lost, while the Confederates had suffered 530 wounded and killed and an additional 500 captured.

The Bloody Angle

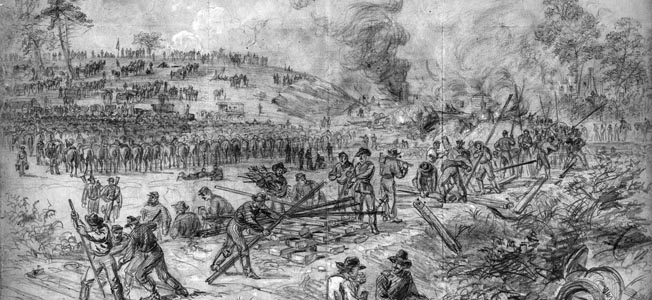

Sheridan’s command spent the night of June 11 camped on the battlefield. The next day the Federals tore up five miles of the Virginia Central. Meanwhile, Hampton established a new defensive position a mile west of the Gordonsville and Charlottesville Road intersection. It was L-shaped and rested behind the Ogg House, with the left anchored along a railroad cut that was reinforced by crude breastworks fashioned from fence rails. This part of the line was held by Butler’s men. Wright’s and Rosser’s brigades extended the line on the right. Artillery was placed along the entire position. Directly across the Gordonsville Road, on the east side of the tracks, defenders manned fortified entrenchments topped with fence rails. Danne’s Store marked the southern end of the Confederate line and the Gentry farm the northern margin.

At 3 pm, Sheridan dispatched Torbert’s division, with Davies’ brigade in support, to the west of Trevilian Station to conduct a reconnaissance of the enemy positions. At the same time, Custer’s command moved along the Gordonsville Road on the left with Merritt’s troopers in the center and Devin’s men on the right. Coming upon Butler’s right, Custer dismounted the 6th and 7th Michigan Regiments on either side of the rail line and sent them forward. After the Wolverines’ attack stalled in the face of severe small-arms and artillery fire, Custer threw in his remaining two regiments. Realizing the superior strength of the enemy’s position, Custer did not press the attack, staying 500 yards away from Wright’s lines for the duration of the battle.

While Custer dithered, at 3:30 pm the reserve brigade came up and connected with Custer’s right flank, occupying an area on the north side of the railroad on the reverse side of the ridge joining Danne’s Store and Gentry’s farm. Devin’s men massed in Custer’s rear. Merritt’s force, in conjunction with three of Devin’s regiments and supported by Williston’s guns, attacked the Confederate left on foot after crossing a 500-yard open field. The target of the Union thrust, which came to be called the Bloody Angle, was held by the 6th South Carolina and two pieces of artillery. Southern musket and cannon fire repulsed the Union assault, and concentrated fire from Hart’s artillery battery silenced the enemy guns.

On the right of Merritt’s line the 6th Pennsylvania and 2nd U.S. Cavalry fought at the Gentry House and in the woods nearby but could not take the homestead. The 6th and 4th New York entered the fight below the Gentry farm, but after pushing some of Butler’s men back across a field they too were forced to retreat by tremendous small-arms fire.

By nightfall Butler had driven back six separate Union attacks along the railroad at or near the Bloody Angle. A seventh erupted after dark as the 6th South Carolina was replenishing its dwindling supply of ammunition. A compact column of Union soldiers managed to reach the Confederate breastworks before breaking and fleeing under heavy fire.

Just before the Federals’ final attack, Lee’s division joined Hampton’s defenders, and Hampton sent Lomax’s and Wickham’s men against the Union right. They were joined by Hampton’s troopers in a dismounted charge that crashed into the surprised left flank of Merritt’s division, hurling the bluecoats back in confusion. A member of the 6th Virginia Cavalry called the Confederate attack “one of those sublime spectacles sometimes witnessed on a battle field.” As Lomax pushed the flank attack, the Federals stampeded toward Trevilian Station. Davies’ brigade covered the retreat. Of the 4,000 Union troops involved in the second day’s fighting, 38 were killed, 169 wounded, and 37 captured. The vast majority of the Union losses were from Torbert’s division. Davies was only lightly engaged and Irvin Gregg not at all.

The Repercussions of Sheridan’s Failure

With part of his command bled dry and hundreds of wounded in need of being transported back to friendly lines, Sheridan had no choice but to retreat. His expedition was a complete failure. He had not destroyed the Virginia Central Railroad, not made contact with Hunter, and would not be able to escort Hunter’s force back to the Army of the Potomac.

With Hampton following close behind but unable to mount a major attack of his own due to his men’s fatigue and lack of supplies, Sheridan moved slowly eastward toward White House Landing on the Pamunkey River, arriving there on June 20 after marching 120 miles and skirmishing daily with Hampton’s pursuers. Sheridan crossed the James River and rejoined the Army of the Potomac on June 25 after skirmishing with Hampton’s exhausted troopers at White House Landing, St. Peter’s Church, and Samaria Church.

Sheridan’s Trevilian campaign had significant repercussions. His failure to destroy large parts of the Central Virginia Railroad and James River Canal allowed vital supplies to reach Lee’s entrenched army at Richmond and Petersburg and enabled other Confederate forces under Maj. Gen. Jubal Early to move by rail to the Shenandoah Valley and open a new front that diverted vital Federal resources from the fight against Robert E. Lee’s army.

The failure at Trevilian Station also called into question Sheridan’s ability as a cavalry commander. Rosser’s claim that Little Phil had displayed no skill at the battle regarding maneuver and that Hampton had whipped him was a criticism Sheridan could never fully shake for the rest of the war. Fairly or not, the accusations spilled over to some of his division and brigade leaders as well.

If Sheridan’s reputation was damaged by the battle at Trevilian Station, Butler’s and Rosser’s were enhanced. Their steady control of their men and coolness in the face of fire marked both as able cavalry commanders. As for Hampton, his stellar performance earned him the overall command of the Cavalry Corps on August 11. His subsequent management of Robert E. Lee’s horsemen throughout the rest of the war reinforced the wisdom of that appointment. For that, Hampton had Phil Sheridan to thank.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments