By Roy Morris Jr.

The two men facing each other across the debate stage at Ottawa, Illinois, on the afternoon of August 21, 1858, were no strangers to one another. Indeed, Senator Stephen Douglas and former one-term congressman Abraham Lincoln had been personal and political opponents—and more or less friendly neighbors—for the better part of two decades. But in ways neither man could imagine, their rivalry was about to grow exponentially and capture the attention of an increasingly divided nation. They would speak to each other, and the rest of the country, in “thunder tones,” as Lincoln would report. And everyone hears thunder when it rolls.

The Arrival of Lincoln and Douglas to Illinois

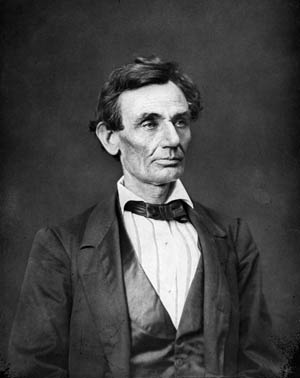

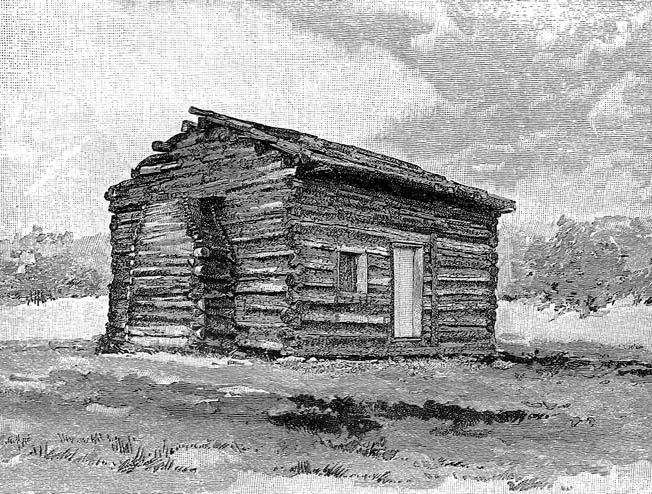

Few political opponents had ever known each other as well or as long as Douglas and Lincoln. Almost from the time they arrived in their adopted home state of Illinois, 16 months apart, in 1831-1832, they had been fated to be rivals on the local, state, and national scene. Lincoln, who was four years older, got there first, literally washing up on the shore of the tiny village of New Salem in the spring of 1831. Residents of the little village awoke one late April morning to see a tall, homely young man sweating mightily in the middle of the Sangamon River, striving to dislodge his makeshift flatboat from its grounding on a dam in the river’s shallows. By the simple but ingenious method of drilling a hole in the boat’s foredeck and shifting barrels of goods to the rear, the boat was tipped over the dam and back into the river. Lincoln and his three companions went on their way, but two months later he returned and settled down in New Salem, where he quickly struck townsfolk as “a very intelligent young man.” Lincoln had made his first significant public impression.

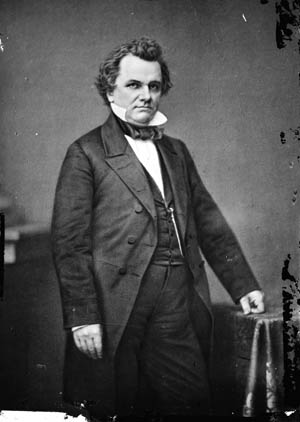

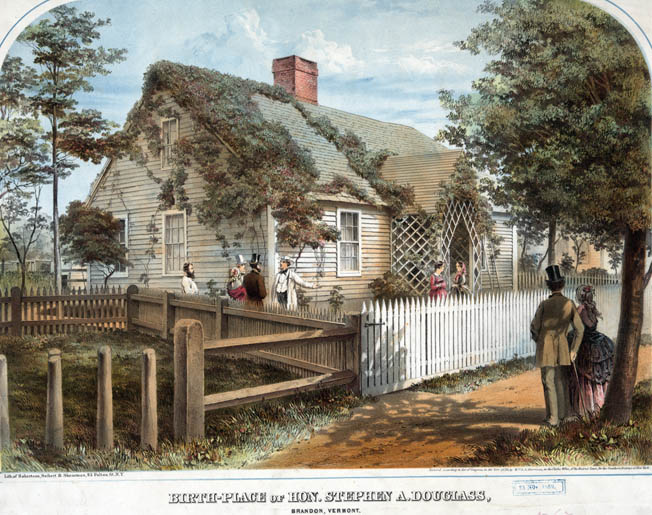

Douglas’s arrival in Illinois 19 months later was considerably less dramatic. He simply rolled into Jacksonville, the seat of Morgan County, aboard a stagecoach in the middle of the night on November 2, 1833. Not yet 21, Douglas had less than $5 in his pocket when he arrived. Like Lincoln, he was following the well-worn path of young men seeking their fortunes on the westward frontier. The chance to reinvent himself in new surroundings was particularly appealing to both Lincoln and Douglas, each of whom was leaving behind a less-than-idyllic home life. Lincoln and his hard-working taciturn father, Thomas, had always had a distant relationship, and by the time he left home, the younger Lincoln had developed a lifelong aversion to physical labor and a thirst to explore the “wider and fairer world” beyond the borders of their Indiana farm.

Douglas, whose own physician father had died when he was two months old, had grown up in Vermont and upstate New York, where he took an early interest in politics and studied law with the leading Democratic politician in Canandaigua, New York, before setting out for the West to seek his fortune. When his mother asked when she would see him again, Douglas responded, “On my way to Congress.” He immediately set out to back up his words, winning election as state’s attorney for the First Judicial District in Illinois in 1834 by a mere four votes and bragging in a letter home that he was “doing as well in my profession as could be expected of a boy of twenty-one.”

One of the new legislators Douglas met in the halls of the state capital at Vandalia was Abraham Lincoln, who had won his own first election (on his second try) to the legislature. Exactly when and how the two men met is unknown. Lincoln later recalled vaguely in 1859 that it had taken place “twenty-two years ago.” Douglas never mentioned a first meeting at all. From the start they were on opposite sides of the aisle: Lincoln was a Whig and Douglas was a Democrat. Whigs, primarily northern and Midwestern in origin, were the party of small shop owners, manufacturers, entrepreneurs, and tradesmen; Democrats, the party of Andrew Jackson, centered their strength in the agrarian South. Whigs favored a weak president, a powerful Congress, and a centralized government that provided a solid infrastructure for interstate trade and commerce. Democrats wanted a strong president but also, conversely, a system based on states’ rights. In the South, of course, the major states’ right was the right to own slaves. On that issue the two parties were fated to do battle.

Lincoln’s Decline, Douglas’ Rise

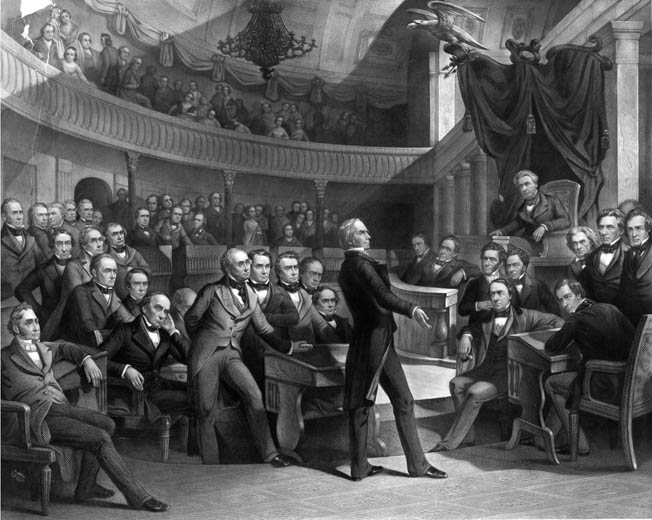

By the time Lincoln and Douglas became politically active in the late 1830s and 1840s, the issue of slavery was a settled fact. The Missouri Compromise of 1820 had outlawed the expansion of slavery into new territories above the 36th Parallel, with the exception of Missouri. The compromise held until the Mexican War, conducted by Democratic President James K. Polk, greatly added to American territories in the West. Whigs, including then-Congressman Abraham Lincoln, opposed the war as a naked power grab by Southern slave owners to expand their reach. A new compromise, in 1850, allowed the recently acquired territory of California to enter the Union as a free state but also put into place a federal Fugitive Slave Law that required Northerners to assist in the return of runaway slaves to their Southern owners. One of the leaders of the Compromise of 1850 was Stephen Douglas, then serving as a U.S. senator.

Lincoln’s opposition to the Mexican War led to his defeat after only one term in Congress. He returned to the private practice of law in his adopted hometown of Springfield, Illinois, while Douglas ascended to the heights of power in the Senate. Douglas also called Springfield home, and he and Lincoln crossed swords several times in the decade prior to the 1850 Compromise. Besides their usual political differences, the two men were also rivals for the hand of a vivacious young Springfield debutante, Kentucky-born Mary Todd. The bright, talkative Mary was a more compatible match for Douglas than she was for the awkward, plain-spoken Lincoln. She and Douglas flirted across Springfield drawing rooms and went on long, chatty walks together. But as a lifelong Whig and a family friend of party leader Henry Clay, Mary could not commit to the Democrat Douglas. “I liked him well enough, but that was all,” she said later. Instead, she married Lincoln in November 1842. It was a marriage based at least as much on political as romantic grounds, but against all odds, it endured for nearly a quarter of a century.

Popular Sovereignty: “A Hell of A Storm”

Following his failure to win reelection to Congress, Lincoln concentrated on his legal career, becoming a highly paid corporate lawyer for a number of Eastern and Midwestern railroads. Meanwhile, Douglas rose to nearly the summit of national politics, becoming the leading Democrat in the Senate and barely losing his party’s presidential nomination to dark horse candidate Franklin Pierce in 1852. As a spokesman himself (and investor) for powerful railroad interests, Douglas championed a new transatlantic railroad. The proposed line he favored would cross the then unincorporated Nebraska Territory en route from Lake Superior to Puget Sound, Washington. “It is utterly impossible to preserve that connection between the Atlantic and the Pacific,” Douglas complained, “if you are to keep a wilderness of two thousand miles in extent between you.” Southern Democrats, however, were in no hurry to create another territory north of the Missouri Compromise line. Missouri Senator David Atkinson, a leading opponent, succinctly spelled out the Southern position. They were willing to see Nebraska “sink in hell” before allowing it to enter the Union as a free state.

Douglas, seeking a way around the opposition—and also a way to protect his recent purchase of 6,0000 acres at the Illinois terminus of the proposed route—sponsored a bill to divide the territory into two parts—Nebraska and Kansas. In theory, this would create a new free state, Nebraska, and a new slave state, Kansas, based on the preferences of their closest neighbors—Iowa and Missouri. It would leave the ultimate decision in the hands of the residents, a move Douglas termed “popular sovereignty.” He reluctantly accepted an amendment to his proposed bill that would repeal the Missouri Compromise in the new territories, although he warned that the change would “raise a hell of a storm.”

“A House Divided Against Itself Cannot Stand”

That storm was not long in coming. The day after he introduced his Kansas-Nebraska bill in the Senate, a group of abolitionist lawmakers released a statement condemning Douglas’s proposal as “a gross violation of a sacred pledge; a criminal betrayal of precious rights; part and parcel of an atrocious plot to exclude from a vast unoccupied region immigrants from the Old World and free laborers from our own states, and convert it into a dreary region of despotism inhabited by masters and slaves.” Douglas, they said, was hatching a monstrous plot to spread “the blight of slavery” across the land and “subjugate the whole country to the yoke of a slaveholding despotism.” Douglas responded that he was merely attempting to insure the survival of “a great principle of self-government,” to “allow the people to legislate for themselves upon the subject of slavery.”

The bill was approved by Congress in May 1854 and signed into law by Democratic President Franklin Pierce. Abraham Lincoln, traveling on legal business when the bill passed, pronounced himself “thunderstruck and stunned. This took us by surprise. We reeled and fell in utter confusion. But we rose each fighting, grasping whatever he could reach—a scythe—a pitchfork—a chopping axe, or a butcher’s cleaver.” His figurative language would soon become literal, as supporters and opponents of the new bill rushed into Kansas Territory to decide whether it would be slave or free.

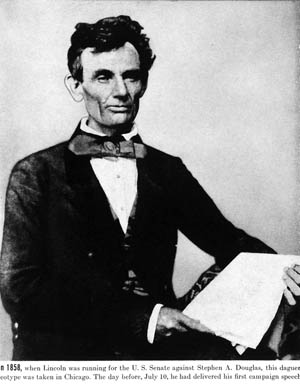

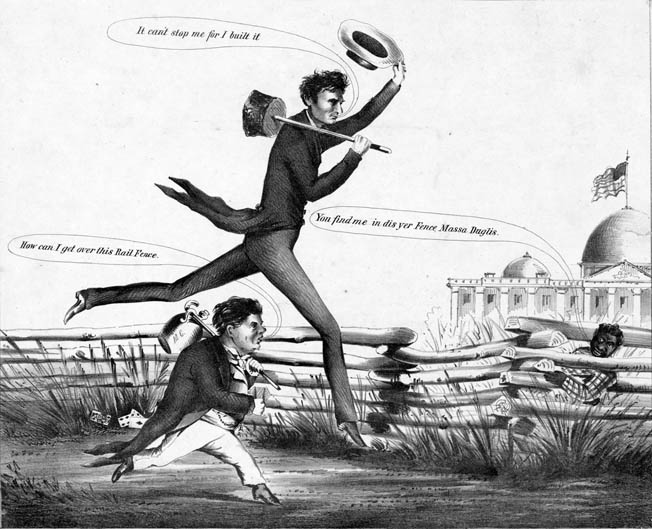

“Bleeding Kansas,” as it soon became called, saw an explosion of violence between the two sides that presaged a wider conflict between the two increasingly intractable regions of the country. The worsening crisis spelled the end of the Whig Party, which was torn in half by the slavery issue, and the rise of a new Republican Party focused entirely in the North. Lincoln soon became a leader of the new party, receiving the nomination to run against his old rival Stephen Douglas for Douglas’s Senate seat in 1858. Lincoln cemented his leadership with an instantly famous speech accepting the party’s nomination. The “House Divided” speech, as it became known, warned that “a house divided against itself cannot stand. I believe this government cannot endure, permanently half slave and half free. I do not expect the Union to be dissolved—I do not expect the house to fall—but I do expect it will cease to be divided. It will become all one thing, or all the other.”

“He is the Strong Man of His Party”

When Douglas heard that the Republicans had nominated Lincoln, he was concerned but not surprised. “I shall have my hands full,” he told Pennsylvania newspaper editor John W. Forney. “He is the strong man of his party—full of wit, facts, dates—and the best stump speaker, with his droll ways and dry jokes, in the West. He is as honest as he is shrewd, and if I beat him my victory will be hardly won.” After some delay, the two men agreed to engage in a series of debates in all but two of the state’s county seats.

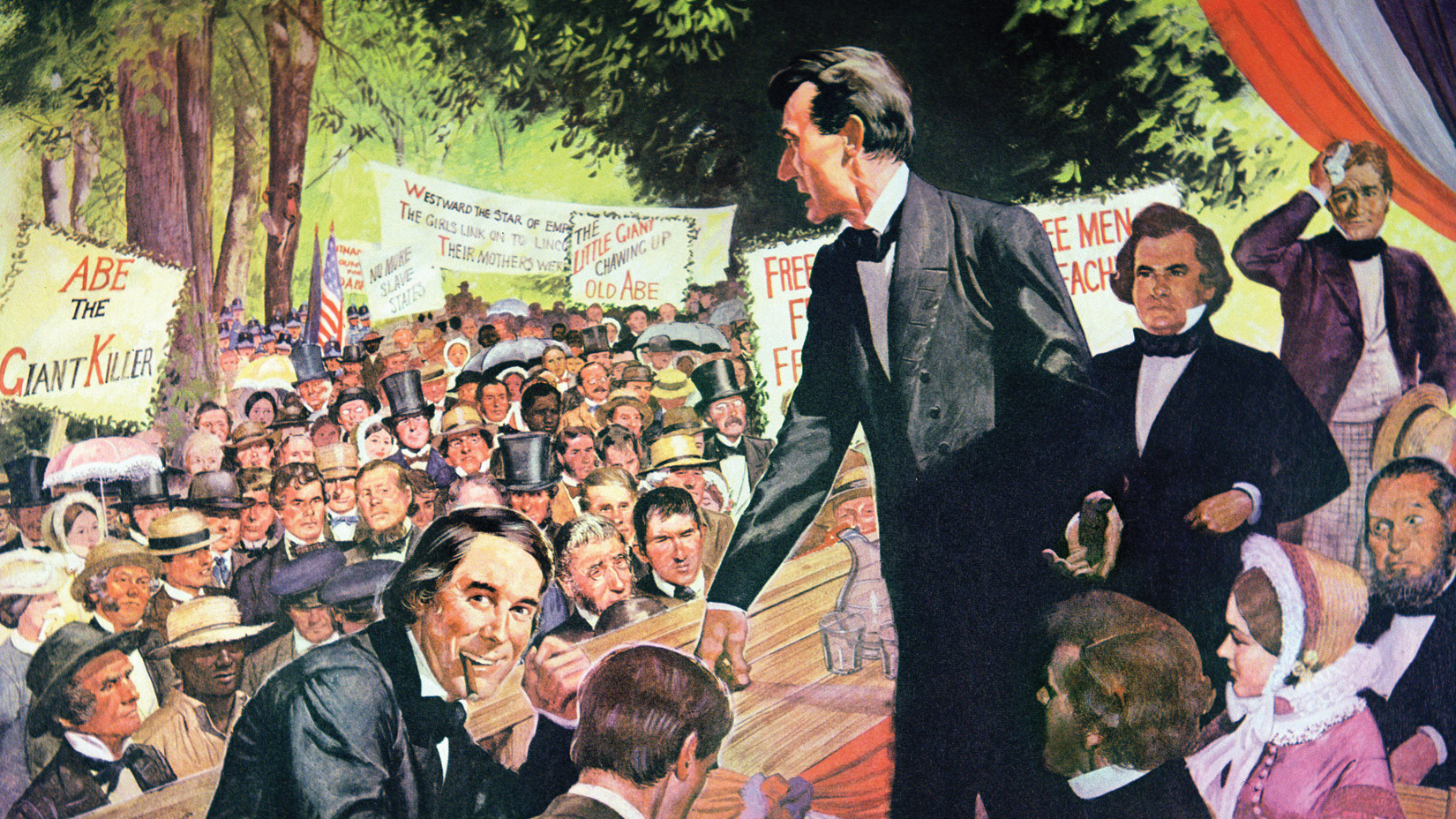

Under guidelines set down by Douglas, as the incumbent, he and Lincoln would meet seven times over the course of the next seven weeks. The first debate was slated for Ottawa, 80 miles southwest of Chicago in the north-central part of the state. It was reliable Republican territory and as such presented Lincoln with the opportunity to get his campaign off to a running start. On August 20, the day before the scheduled debate, huge crowds of people began flocking into the little town (population 9,000), which sat between the Fox and Illinois Rivers. Men, women, and children poured into town on foot, horseback, wagons, railroad trains, and canal boats blazing with partisan political banners. By eight o’clock on the morning of the debate, Ottawa’s population had tripled, with the huge crowds kicking up clouds of dust until Ottawa looked like “a vast smoke house” in the evocative words of a Chicago Tribune correspondent.

The two candidates arrived separately. Lincoln came by train from Chicago, pulling in at noon to the Rock Island depot, where he was met by Ottawa mayor Joseph O. Glover and escorted to Glover’s home by a half-mile-long parade of supporters. Douglas entered town from the west, his elegant private carriage drawn by six white horses. Like Lincoln he opted to freshen up before the debate, checking into the Geiger House while his supporters marched back and forth in front of the hotel, hurrahing their hero with loud cheers and improvised music.

The audience crammed into Lafayette Square an hour before the scheduled 2 pm starting time. There were no chairs and few trees, and the late summer sun pounded down mercilessly on everyone. Vendors sold water and lemonade; more potent liquid refreshments were also available. The stage, a simple platform of unfinished wood, was topped by a flimsy awning. No one had thought to guard the stage, and it took a good 30 minutes to clear a space for the candidates and local dignitaries. Meanwhile, village clowns dangled precariously from the awning to the delight of the crowds. In short order the awning gave way, toppling the miscreants into the laps of the front-row crowd. Everyone enjoyed the spectacle.

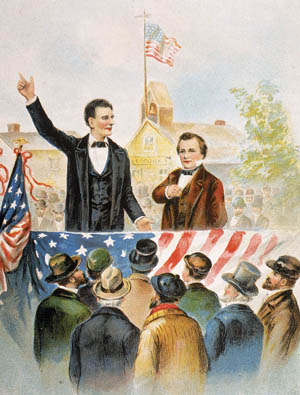

The candidates arrived a few minutes later and climbed with difficulty onto the stage. Lincoln, wearing a simple dark suit, sat at the end of the front row, a worn carpetbag filled with notes and copies of old speeches at his feet, while Douglas stepped to the front of the stage. He was dressed, planter-style, in a wide-brimmed white hat, ruffled shirt, light trousers, and dark blue coat with polished buttons. Under the agreed upon format, Douglas would speak first for an hour, Lincoln would have 90 minutes to respond, and Douglas would conclude with a 30-minute rebuttal. The order would alternate for each subsequent debate.

The First Debate: Douglas on the Offensive

Having faced Lincoln many times in the past, Douglas confidently took the offensive. Like a skilled prosecuting attorney confronting a petty defendant, Douglas threw a series of sharp questions at his obviously startled opponent, demanding to know Lincoln’s positions on the Fugitive Slave Act, the slave trade in general, the admission of new states to the Union, and popular sovereignty in the territories. Introducing a theme that would run through the debates, Douglas raised the doleful specter of black citizenship, charging that the Republicans favored bestowing immediate and full civil rights on African Americans, a move he warned would “cover our prairies with [black] settlements and turn this beautiful state into a free Negro colony.” Douglas accused Lincoln of believing that black men were “his equal, and hence his brother. I do not regard the Negro as my equal, and positively deny that he is my brother or any kin to me whatever.”

Thrown off balance by Douglass’s aggressive opening gambit, Lincoln offered a weak rebuttal, denying that he had conspired to form a new abolitionist party in Illinois and reading a long, boring excerpt from his old speech in Peoria. Douglas, he charged, was attempting to twist Lincoln’s beliefs into “a specious and fantastic arrangement of words, by which a man can prove a horse chestnut to be a chestnut horse.” As for the charge that Lincoln believed in racial equality, Lincoln frankly asserted; “I have no disposition to introduce political and social equality between the white and the black races. There is a physical difference between the two, which in my judgment will probably forever forbid their living together on terms of respect, social and political equality.”

Besides their pronounced political differences, the candidates presented diametrically opposite public faces. Douglas was all clenched fists and high dudgeon, shouting out accusations in his surprisingly deep, mellow voice. Lincoln, although much taller, had a comparatively higher, shriller voice and presented a much less polished stage presence, fumbling with his glasses—-“I am no longer a young man”—and bending awkwardly at the knees before suddenly springing upward in an ungainly but compelling gesture of emphasis. Three times during Douglas’s speech Lincoln attempted to interrupt him, causing fellow Republican committeemen on stage to hiss: “What are you making such a fuss for? Douglas didn’t interrupt you, and can’t you see the people don’t like it?” With some difficulty, Lincoln managed to rein in his temper.

“Charge, Chester! Charge!”

After the debate, supporters carried Lincoln off on their shoulders, his long underwear comically showing beneath his pulled-up pant legs. The partisan press judged the outcome along predictable party lines. The Democratic-leaning Chicago Times judged Douglas’s “excoriation of Lincoln” to have been “so severe that the Republicans hung their heads in shame,” while Republican newspapers thought Lincoln had appeared “high toned” and “powerful” in the face of the senator’s “boorish” assaults. Prominent New York editor Horace Greeley anointed the debate nothing less than “a contest for the Kingdom of Heaven or the Kingdom of Satan.” A well-known founder of the Republican Party, he left no doubt about which kingdom Lincoln belonged to.

Lincoln was sufficiently worried about his performance in Ottawa to convene a meeting of his brain trust in Chicago a few days later. While pronouncing himself reasonably satisfied with the outcome of the debate—“The fire flew some, and I am glad to know I am yet alive”—he invited suggestions on how he could improve his performance. Chicago Tribune editor Joseph Medill, a longtime supporter, urged Lincoln to be more aggressive. “Don’t act on the defensive at all,” Medill advised. Instead, “Hold Doug up as a traitor and conspirator and a pro-slavery bamboozling demagogue.” Medill told Lincoln to “put a few ugly questions” of his own to Douglas, noting, perhaps unnecessarily, “You are dealing with a bold, brazen, lying rascal and you must fight the devil with fire. Give him hell.” Another supporter, Charles Ray, urged, “Charge, Chester! Charge! Do not keep on the defensive. We must not be parrying all the while. We want the deadliest thrusts. Let us see blood follow any time [Douglas] closes a sentence.”

Fighting on the “Freeport Doctrine”

The second debate took place on August 27 at Freeport, six hours by train from Chicago and a few miles from the Illinois-Wisconsin border. The candidates arrived to the already standard salvos of cannon fire and shouting supporters. It was a damp, overcast day, but 15,000 spectators—twice the town’s population—flocked into a vacant lot near the banks of the Pecatonica River, where another crude wooden platform had been erected between two trees. Lincoln again arrived first, sitting atop a Conestoga wagon accompanied by an honor guard of humble farmers to emphasize his rural roots. Douglas walked over the square from his room at the Brewster House hotel. Along the way a watermelon rind arced through the crowd and struck Douglas on the shoulder as he mounted the stage. He threatened to leave at once.

Lincoln, going first, said he wanted to respond to Douglas’s “seven distinct interrogatories” from the previous debate. He denied favoring repeal of the Fugitive Slave Law, the abolition of slavery in the District of Columbia, the prohibition of slave trade between the territories, or the admission of new slave states to the Union. He supported the right of people within a new state to draft “such a constitution as they may see fit,” but he also supported the right of Congress to prohibit slavery in all territories. Finally, he waffled on the question of whether he opposed acquiring new territories unless slavery was first prohibited within their borders. “I would or would not oppose such acquisition,” he said weakly, “according as I might think such acquisition would or would not aggravate the slavery question among ourselves.” He demanded to know if Douglas believed that the people of a new territory could legally exclude slavery within its own borders “prior to the formulation of a state constitution.”

As Lincoln, Douglas, and all discerning listeners immediately understood, this was the crux of the entire campaign. By championing the Kansas-Nebraska Act, Douglas had gone on record as supporting popular sovereignty. But conflicting pro- and anti-slavery constitutions had been presented in Kansas, and President James Buchanan—against Douglas’s advice—had recognized the pro-slavery Lecompton Constitution (so named for the town in which the pro-slavery legislature was sitting). “Kansas,” said Buchanan, “is therefore at this moment as much a slave state as Georgia and South Carolina.” Douglas had denounced the state constitution as “a fraudulent submission” and “a violation of the fundamental principle of free government.” Kansas remained, for the time being, an unincorporated territory.

Now, answering Lincoln’s interrogation, Douglas reiterated his view that the people of a territory already “have the lawful means to introduce slavery or exclude it as they please, for the reason that slavery cannot exist a day or an hour anywhere unless it is supported by local police regulations. Those police regulations can only be established by the local legislature, and if the people are opposed to slavery they will elect representatives to that body who will by unfriendly legislation effectually prevent the introduction of it into their midst.” He was only stating the obvious, but Douglas’s “Freeport Doctrine” would come back to haunt him by comprehensively alienating southern Democrats—as Lincoln had cannily foreseen.

A Crowd at Charleston

From Freeport the candidates traveled to Jonesboro, in the southernmost part of the state, nicknamed Egypt after its best-known town, Cairo (pronounced, frontier-style, Kay-Ro). Jonesboro was safe territory for Douglas and the Democrats— Republican presidential nominee Jon C. Fremont had won less than four percent of the vote in the last election—but it was also small and isolated, with only 800 residents. Further depressing turnout that day was the fact that the state fair was underway at nearby Centralia, and many local farmers had opted to view giant rutabagas and corn-fattened hogs rather than stick around to listen to the two senatorial candidates. Only about 1,500 people turned out for the debate, which devolved into a question of whether or not Lincoln and other like-minded politicians were secretly campaigning beneath “the black flag of Abolitionism.” “Suppose Mr. Lincoln should die, what a horrible condition would they be in,” Douglas conjectured—allowing Lincoln to steal a laugh from the pro-Democratic crowd by loudly groaning at the sheer horror of such a thought. Lincoln uncharacteristically concluded his own remarks with 10 minutes to spare, leading the Chicago Times to comment afterward, “We fancy he has had enough of Egypt, and certainly Egypt has had enough of him.”

Three days later Lincoln was on friendlier soil at Charleston in the extreme eastern corner of the state. Indeed, he was something of a favorite son, having immigrated to Coles County from nearby Indiana at the age of 19. His widowed stepmother, Sarah Bush Johnston Lincoln, still lived in a log cabin in the area. An enormous 80-foot-wide banner hung across Main Street, showing the young Lincoln driving an oxcart into the village during “Abe’s Entrance to Charleston Thirty Years Ago.” Another banner showed a giant Lincoln clubbing a cringing Douglas into submission with his mighty fists. Douglas, unamused, threatened to leave at once after he saw the offending poster but rallied his forces behind a brass band and a parade of 32 pretty young women representing the 32 states in the Union. Lincoln also led a wagonload of pretty girls down the street—it seemed to be the theme of the day—under the banner, “Girls Link-on to Lincoln.”

A huge crowd of nearly 15,000 people attended the debate at the agricultural society fairgrounds. Noting an enormous Democratic banner decrying “Negro Equality,” Lincoln began his remarks with an apocryphal question he said “an elderly gentleman” had asked him about whether Lincoln was really in favor of “social and political equality of the white and black races.” He was not, Lincoln said, adding that physical differences “will forever forbid the two races living together upon terms of social and political equality.” He added, in a lame attempt at humor, “I do not understand that because I do not want a Negro woman for a slave I must necessarily want her for a wife. My understanding is that I can just leave her alone.” He suggested that since Douglas seemed to be so worried about intermarriage, he should give up his Senate seat and return to the state legislature, which was the only governing body that could legally change Illinois’s existing miscegenation laws. Douglas responded drolly that he was glad to have Lincoln’s advice on the subject.

Property Rights vs Human Rights

The largest crowd of the debates assembled at Galesburg in the northwestern part of the state. An estimated 15,000-20,000 people braved an “Arctic frost” of biting winds and cold rain to see the candidates make their usual entrance by train and buggy. The two were driven to Knox College, the site of the debate, in side-by-side carriages. The stage had been moved to a spot alongside the college building to shield the candidates—but not the crowd—from the wind, forcing the guests of honor to climb through a first-floor window onto the stage. (Lincoln quipped, “Well, at last I have gone through college.”) Galesburg was an old stop on the Underground Railroad, and most of the crowd consisted of pro-Lincoln college students.

The strong wind made it hard for the speakers to be heard—or even to speak. Douglas took a throat lozenge before taking his turn on stage and politely offered another to Lincoln. He reminded the crowd that Lincoln had spoken out against racial equality at Charleston after favoring it at other stops. “His creed don’t travel,” Douglas scoffed. Lincoln denied that he had been inconsistent, noting, “I have always maintained that in the right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, [blacks] were our equals.” He contrasted his position to Douglas’s legalistic insistence on property rights over human rights. “He insists, upon the score of equality, that the owner of slaves and the owner of horses should be allowed to take them alike to new territory and hold them there,” said Lincoln. “That is perfectly logical if the species of property is perfectly alike, but if you admit that one of them is wrong, then you cannot admit any equality between right and wrong. I believe that slavery is wrong. There is the difference between Judge Douglas and his friends and the Republican Party.”

Debate on the Illinois-Missouri Border

Six days later the campaign pulled into the Mississippi River town of Quincy on the extreme western edge of the Illinois-Missouri border. Boats steaming downriver from Hannibal, Missouri, and upriver from Keokuk, Iowa, swelled the turnout to nearly 15,000 people. After several days of heavy rain, the day of the debate broke sunny and cool. Lincoln was escorted to the debate site by yet another parade of supporters, this group pulling a horse-drawn model of the USS Constitution piloted for some reason by a live cartoon, the symbol of the now extinct Whig Party. The stage in Washington Square was made of large pine boards, and before Lincoln could begin his remarks the railing gave way, sending dozens of local dignitaries crashing to the ground. No sooner had they regained their footing than another bench, this one reserved for the ladies in attendance, also gave way, leaving the fairer victims to reel dazedly into the arms of their rescuers, bonnets and petticoats askew.

Once again Lincoln denounced slavery as a spreading evil and repeated his claim that Douglas and the Democrats were conspiring to make the practice both national and permanent. After Douglas retaliated by criticizing Lincoln for ignoring the Supreme Court’s Dred Scott decision, Lincoln, perhaps rattled by the collapsible stage, got into a shouting match with a Chicago Times reporter in the crowd. “I don’t care if your hireling does say I did,” Lincoln roared, “I tell you myself that I never said the Democratic owners of Dred Scott got up the case.” On that less than elevated note, the sixth debate came to an end.

Setting the Stage For the Lincoln Presidency… and the Civil War

The seventh and final debate took place on October 15 in Alton 115 miles downriver from Quincy. Despite beautiful fall weather and a special $1 round-trip riverboat ticket from nearby St. Louis, only 5,000 people—the second smallest turnout of the series—showed up at Alton’s new city hall for the event. Perhaps, as a Cincinnati newspaper reporter conjectured, “the novelty had worn off” the debates. Douglas’s voice had been reduced by now to a hoarse whisper, and he could scarcely be heard over the crowd. Quoting Lincoln’s earlier statement that he would be “exceedingly sorry ever to be put in the position” of having to vote on the admission of new slave states to the Union, Douglas made one of his rare jokes: “Permit me to remark that I don’t think the people will ever force him into a position where he will have to vote upon it.” Lincoln joined good naturedly in the laughter.

Buoyed by the presence of his wife and eldest son, Robert, at the debate, Lincoln gave one of his strongest performances. He confessed that he was “not less selfish than other men” in seeking high political office, “but I do claim that I am not more selfish than is Judge Douglas.” (“Roars of laughter,” the Chicago Tribune reported parenthetically.) The chief difference between the two sides, said Lincoln, was that one considered slavery to be wrong, while the other did not. “That is the real issue,” Lincoln concluded, “an issue that will continue in this country when these poor tongues of Douglas and myself shall be silent.”

Lincoln was both right and wrong in that assessment. The explosive issue of slavery would continue to rage after the debates were over, but both he and Douglas would also continue to have a real say in future events. That November the Democratic-controlled Illinois Legislature returned Douglas to the Senate over Lincoln, although Republicans won the only statewide election, that of state treasurer, by 3,800 votes. But as Douglas had presciently argued during the campaign, the Republicans were setting the stage for a presidential campaign in two years, during which they would “connect the northern states into one great sectional party, and inasmuch as the northern section is the stronger, the stronger section will out-vote and control and govern the weaker section.” In his worst nightmare, he couldn’t have foreseen that Abraham Lincoln would be the one doing the controlling and governing.

As for Lincoln, his first reaction to losing the senatorial election was amused chagrin. “I feel like the boy who stumped his toe,” he told visitors to his law office in Springfield. “I am too big to cry and too badly hurt to laugh.” He tried to take the longer view, recalling that on election night he had nearly lost his footing on a rain-slick path. Lincoln remembered telling himself then, “It’s a slip and not a fall.” He viewed the just concluded campaign in a similar light. “I am glad I made the late race,” he said. “It gave me a hearing on the great and durable question of the age, which I could have had in no other way; and though I now sink out of view, and shall be forgotten, I believe I have made some marks which will tell for the cause of civil liberty long after I am gone.” He was not gone yet.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments