By Pedro Garcia

The prospect of running the Federal blockade at Wilmington was easy in the beginning. North Carolina’s principal seaport was blockaded by a single warship, USS Daylight, and no one took the threat seriously. The Wilmington Journal scoffed, “Daylight is a little cock-a-hoop of a thing, and a good sound shot from a rifled cannon would open daylight through her. We must get the thing up here to go a-fishing in.” Southerners could afford to joke about the naval blockade in 1861—the so-called Anaconda Plan. Equipped with 50 warships more or less, the Federals had to blockade 3,550 miles of coastline, 189 harbors or inlets, and nine major seaports. However, by the close of 1864, Southerners found nothing humorous about the blockade, as almost 500 enemy warships patrolled the coastline and rivers with increasing impunity.

Evading the talons of the U.S. Navy was not an easy task for blockade runners; the odds of capture, one in 10 in 1861, were now one in three. For the 33 warships that maintained the Wilmington blockade, duty was routinely mundane, punctuated by moments of high drama. Aboard each ship, a deck officer posted aloft in the bosun’s chair scanned the horizon—the moonless nights favored blockade runners—straining to spot the silhouette of a runner or a distant plume of smoke. If a runner was spotted, a signal rocket would split the darkness, sending seamen to their battle stations, and with steam up, the chase was on. Firing rocket after rocket to mark the runner’s path, the blockaders would pursue their quarry. Hurriedly shoveling pitch pine and rosin chunks into the ship’s furnace, the ship’s firemen stoked a hotter fire to build speed. Aboard the harried blockade runner, firemen would fuel the ship’s furnace with sides of bacon or turpentine-soaked cotton to build enough speed to outrun their pursuer.

Narrow escapes were common, but when capture seemed imminent a captain would heave to and surrender. More often, he would turn toward shore and try to beach his vessel in the breakers, hoping his cargo could be salvaged later. Sometimes a lighter moment highlighted the chase. Commander John Almy of the USS Connecticut once pursued a Wilmington-bound blockade runner for 70 miles before finally running her down and boarding her. As his sailors searched the confiscated booty, Almy came aboard and greeted her captain. “Good Morning, glad to see you.” The hapless captain replied, “Damned if I’m glad to see you.” It was not difficult for the Confederates to be constantly reminded of the Union naval threat. By December 1864, the beaches and sand dunes at the mouth of the Cape Fear River, which connected Wilmington to the Atlantic, were littered with the skeletal remains of at least 60 blockade runners that had been captured or forced aground by Federal blockaders.

The Gibraltar of the South

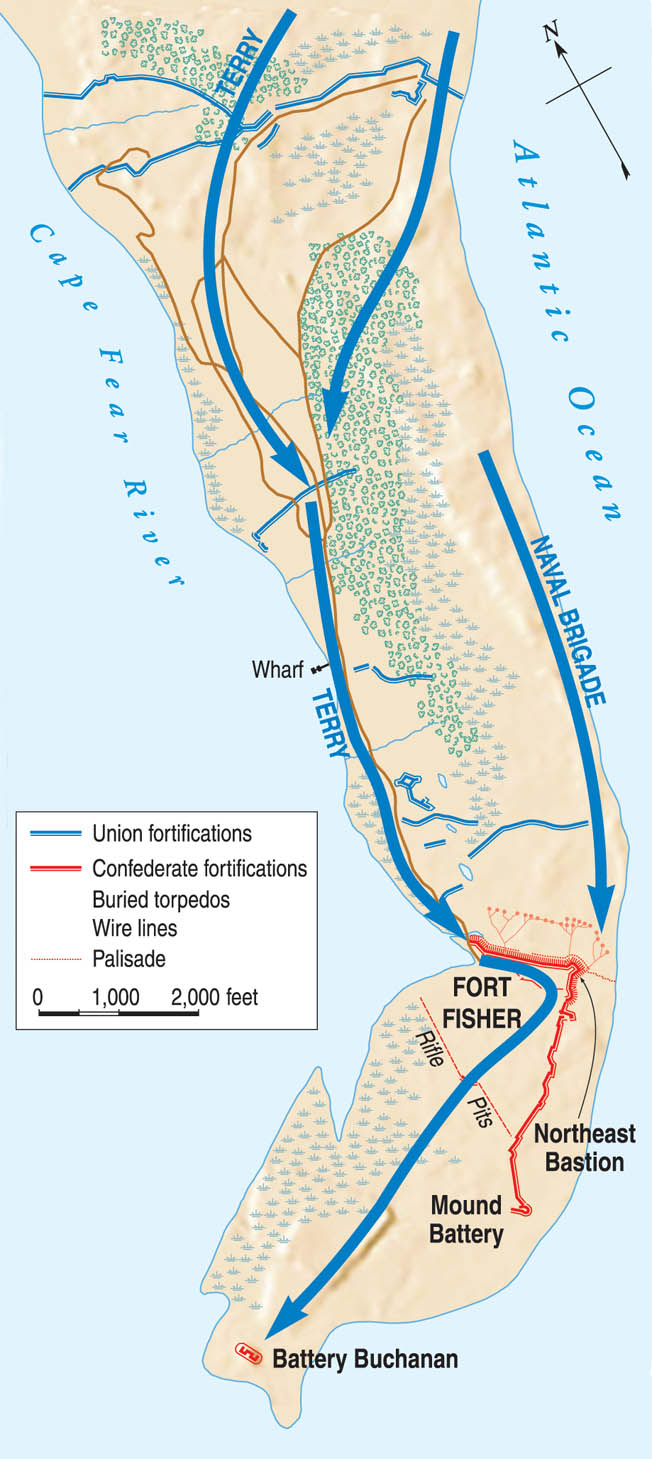

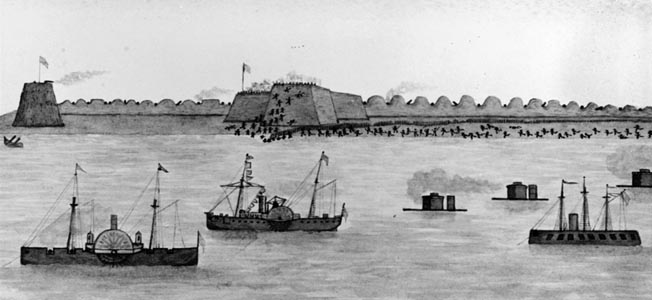

On December 24, the day Savannah fell to Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman at the conclusion of his audacious March to the Sea, the Union Navy prepared to unleash a formidable amphibious operation against Fort Fisher, which defended Wilmington, the single most important port for blockade runners. The Tarheel seaport had become far more important than any other Southern port, the only one capable of maintaining a lifeline for the Confederacy. The fate of Wilmington, and perhaps even the Confederacy itself, rested with Fort Fisher. A world-class fortification known as the “Gibraltar of the South,” the fort was considered to be stronger than the celebrated Fort Malakoff at Sevastopol during the Crimean War. Located 18 miles south of Wilmington, Fort Fisher straddled Confederate Point, formerly known as Federal Point, a long, tapering peninsula between the Cape Fear River and the Atlantic. At its mouth, Cape Fear split around Smith’s Island, spilling into the ocean through two inlets—New Inlet to the north and Old Inlet to the south. Fort Fisher, which dominated New Inlet, was the anchor of the Cape Fear defense system, a remarkable network of fortifications that encircled Wilmington and extended downriver on both banks. Fort Caswell, a formidable looking masonry fort, overlooked Old Inlet, and the rest were composed of mutually supporting earthworks that bristled with wide-muzzled heavy artillery pieces.

When Colonel William Lamb assumed command of Fort Fisher on July 4, 1862, it was not much more than a collection of earthworks consisting of six artillery batteries mounting 17 guns. Over the span of two years, and under his self-possessed guidance, Lamb transformed the fledgling fort into the ultimate earthen fortification, particularly efficient at absorbing salvos of heavy ordnance. Built in the shape of an upside-down L, the sprawling fortress stretched almost a half-mile across Confederate Point, from river to ocean, then snaked more than mile down the beach. The landface section was a bumpy line of 15 huge earthen mounds, called traverses, which were approximately 30 feet high and 25 feet thick, and was bombproofed with a hollow interior to shelter the garrison during a bombardment. Between the traverses, heavy artillery was mounted in elevated gun chambers, which consisted of 20 heavy seacoast pieces, mostly large Columbiads, supported by several field pieces and three mortars. At the angle of the L, where the landface intersected the seaface, a massive earthwork called the Northeast Bastion rose 43 feet above the beach, providing a sweeping view for miles. From the Northeast Bastion, the fort’s seaface ran along the beach in another line of bumpy, sodded traverses and gun chambers, 24 pieces of heavy artillery, including a mammoth 150-pounder Armstrong rifled cannon. The seaface was punctuated by a mountainous, 60-foot-high artillery emplacement known as the Mound Battery, which mounted a beacon at its pinnacle to signal blockade runners.

Nearby, a telegraph station had been erected with lines running all the way to district headquarters in Wilmington. At the tip of Confederate Point, Lamb had built Battery Buchanan to protect New Inlet and the fort’s rear. Fort Fisher also boasted the latest technology: an electrically detonated minefield of torpedoes, iron cylinders filled with 100 pounds of black powder, and specially wired artillery shells, all of which were connected to an underground network of wires linked to a primitive electric battery. However, the sprawling fortress was woefully undermanned with inexperienced troops. Although the garrison had more than doubled in the 2½ years since he assumed command, Lamb could count only on 600 troops of the 36th North Carolina Regiment.

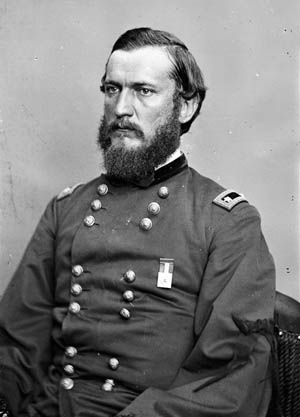

Commanders of the Battle of Fort Fisher

Wilmington’s increasing importance to the Confederacy had long been obvious to Union war planners. By the end of 1864, it became more so. General-in-Chief Ulysses S. Grant had become interested in supporting Sherman’s drive into the Carolinas, and the Cape Fear River was an ideal logistical artery to supply Sherman’s army. Even so, Grant’s approval for an expedition against the fort was conditional: he wanted an aggressive naval commander to lead the attack. He got one in Admiral David Dixon Porter, by far the most successful officer in the Union Navy for combined operations. The two men were well acquainted since the Vicksburg campaign the previous year. The tough, 51-year-old admiral was ambitious, politically astute, extremely self-confident, and resourceful. An often pretentious officer, Porter frequently irritated his peers. A newspaper correspondent described Porter as “vain, arrogant, and egotistical to an extent that can neither be described or exaggerated.”

Grant’s choice for the mission’s army commander was Brig. Gen. Godfrey Weitzel, a corps commander and chief engineer for the Army of the James. But in a surprising move, Weitzel’s immediate superior, Maj. Gen. Benjamin Butler, decided to assume command of the expedition himself. A political general from Massachusetts, Butler was one of the most controversial officers in the Union Army. He had boundless ambition and a total lack of scruples, and he saw himself as a presidential possibility. “I will always think of old Ben as a cross-eyed cuttle fish swimming about in waters of his own muddying,” remembered one fellow general. Soldiers might consider him a bottom-feeder, but abolitionists and bitter-enders thought him a hero. Grant, for his part, had little confidence in Butler. Porter had even less—the two men despised each other. The feud had begun in 1862 when Butler criticized Porter’s role in the capture of New Orleans. The animus cultivated an atmosphere of noncooperation that infected the Fort Fisher expedition from the beginning. The situation worsened because the men held joint command, with neither having final authority. It was recipe for disaster.

Gloom had pervaded Fort Fisher since October 24, when Lamb first learned that Federal forces were gathering at Beaufort and that an attack on the fort was imminent. As he prepared for battle, Lamb was saddled with another serious worry. His longtime friend, mentor, and military commander, Maj. Gen. William Henry Chase Whiting, was abruptly relieved of command. Whiting, a brilliant engineer whose ideas had been a driving force at Fort Fisher, had incurred the mistrust of President Jefferson Davis, who replaced Whiting with Davis’s friend and military adviser, General Braxton Bragg. A feckless loser with an unbroken record of futility, Bragg’s appointment was widely viewed as calamitous. The Richmond Examiner editorialized, “Bragg sent to Wilmington. Goodbye Wilmington.”

Within a month of his arrival, Bragg left for Augusta to assume temporary command of a Confederate force being assembled to slow down Sherman’s juggernaut. In his absence, Whiting was left in charge of his old command, but he was dismayed to discover that half of Fort Fisher’s garrison had gone with Bragg. Whiting was further disappointed to receive orders from General Robert E. Lee to send 1,500 more troops from the Cape Fear region north to Weldon to oppose a Union diversion near there. As Fort Fisher’s defenders readied themselves for the impending attack, the garrison counted fewer than 800 troops, and Whiting anxiously complained, “It’s an ungrateful duty, this, and no bed of roses, and the prospect is not particularly cheerful ahead. Between Bragg and Lee, Sherman and Grant, old North Carolina is in a pretty fix.” Bragg dismissed Whiting as an alarmist, and on December 17 he returned to Wilmington to resume command—without the troops he had taken with him. The next day, Lee dispatched Maj. Gen. Robert F. Hoke’s hard-hitting veteran division to take up the slack. It was debatable whether it would arrive in time.

A Boat Filled With Powder

Meanwhile, Butler had a bright idea. He planned to destroy Fort Fisher by exploding a ship filled with gunpowder as close to the ramparts as possible. Butler believed the blast would unleash the force of a tornado and that the resulting shockwave would flatten the fort’s walls, killing most of its garrison, and that any survivors would probably suffocate on poisonous gases. Selected for the job was the USS Louisiana, an aging, flat-bottom boat that had the required shallow draft to run in near to shore. The 295-ton vessel was packed with 200 tons of gunpowder, transforming her into a seagoing powder keg. On December 14, a contingent of 6,500 soldiers boarded transports at Hampton Roads and steamed south, anchoring 18 miles north of Fort Fisher. They followed on the heels of Porter’s armada of 56 warships.

Porter announced his arrival to Butler with a dispatch. The message made no reference to the fleet’s delay, and by the 18th the army was in its third day of waiting. Butler and his officers lamented the lost opportunity to make an easy landing, and the troops began to wonder why they were not taking advantage of the perfect weather conditions to go ashore. The two old adversaries made no attempt to meet, communicating instead by dispatch. The next morning light swells replaced the calm waters. By dusk the wind was blowing hard, the sea was rolling in whitecaps, and a fierce northeaster struck with stunning violence, lasting for two days. The landing would have to be postponed until the storm ended, so Butler decided to return the troop transports to Beaufort to ride it out. While there, he wired Grant a terse telegram: “Have done nothing—been waiting for navy and weather.”

Despite hurricane-force winds, the naval fleet rode out the storm five miles off Fort Fisher without loss of life or vessel. Then, with his fleet intact, Porter made the unilateral decision not to wait for the squint-eyed general or his army to return. The navy would explode the powder boat against Fort Fisher. When he received the news, Butler was livid. A glory hog himself, it was obvious to Butler that Porter wanted to destroy Fort Fisher in the army’s absence and claim all the credit. In preparation, Porter took his fleet 12 miles farther out to sea and ordered all his ships to release steam from their boilers to prevent them from being ruptured by the distant explosion.

Blasting Fort Fisher

On the night of December 24, Louisiana was towed to within 600 yards of Fort Fisher. At 1:46 am she exploded with a towering geyser of flame, followed by a thunderous roar and a series of loud booms. A correspondent for the New York Times reported that the explosion “produced a deep, heavy blast and a colossal wall of gray smoke that rose from the shoreline and rolled silently toward the fleet like a massive thundercloud. As it rose rapidly in the air, and came swiftly toward us on the wings of the wind, it presented a most remarkable appearance, assuming the shape of a monstrous waterspout, its tapering base seemingly resting on the sea. In a very few minutes it passed us, filling the atmosphere with its sulphurous odor, as if a spirit from the infernal regions had swept over us.”

Remarkably, the fort remained largely undamaged. In fact the explosion made so little impression on the defenders that they vaguely supposed a Yankee boiler had burst. Not even the marsh grass on the fort’s sloping walls was disturbed. If the explosion was anticlimactic, what followed over the next two days was even worse. Porter’s warships hove into view at Fort Fisher, and he deployed them into four lines with an ironclad division anchored three-quarters of a mile off the beach. The three forward lines would bombard the fort, and the fourth line would replace damaged ships and cover troop landings. Inside the fort, Lamb ordered the drummer boy to beat the long roll sending soldiers and gun crews to their battle stations. Lamb had only 3,000 rounds for the fort’s 44 guns, fewer than 70 rounds per gun, and for the monster Armstrong cannon he had only 13 rounds. To preserve the limited ammunition he issued strict orders. Only the long-range artillery would be fired regularly, and no gun would be fired more than once every half hour. The gunners understood the purpose of the order—every shot must count.

At 12:45 pm, the grim silence was broken by a shrieking shell from the mammoth iron-plated warship USS Ironsides. The shot missed its intended target, the flagstaff atop the Northeast Bastion. In response, Lamb ordered the fort’s signal gun fired, and a huge Columbiad belched a solid shot that ricocheted off the smooth sea toward the USS Susquehanna. The projectile jumped over the ship’s railing and punched a hole in her smokestack. Instantly, the fort’s gunners jumped to action, and all the batteries on the seaface bellowed and spat flame and smoke. The long lines of warships replied with a stunning barrage, a fiery mile-wide swarm of shot and shell, exploding overhead in showers of spinning iron that raised geysers of sand, plowed up the fort’s sandy interior, or splashed harmlessly into the Cape Fear River in the rear. “It was a magnificent sight,” a Federal naval officer noted, “and one never to be forgotten. The ships’ sides seemed a sheet of flame, and the roar of their guns like a mighty thunderbolt. Nothing could withstand such a storm of shot and shell as was now poured into this fort.”

Shells tore into the fort’s eastern walls, ripping jagged holes in whitewashed structures, bursting among the barracks and stables and setting them ablaze. Meanwhile, the garrison remained inside their bombproofs, protected from the enemy fire. As planned, they emerged occasionally to fire their guns. Restricted by orders to fire infrequently, the gunners had difficulty finding the range, and although they scored three direct hits, many overshot the Union warships. Despite frequently overshooting the mark, the naval bombardment took a toll on the crater-filled and smoldering fort. Near sunset, Butler finally arrived with three troop transports. The rest would be along shortly, he said—much to Porter’s disgust, since the day was too far gone to attempt a landing.

The Fort Survives

Disgruntled, Porter ordered a cease-fire at 5:30 pm. The fleet had lost 83 dead and wounded, more than half of them mangled by the explosion of five new 100-pounder Parrott guns on the sloops and frigates. Ashore, Lamb took stock of his damage—two guns disabled, four mangled but serviceable, 23 casualties including four dead or mortally wounded. The fort itself had been badly cut up, its barracks and stables in ashes, but its fighting efficiency had not been seriously impaired. Porter believed otherwise. He was certain the fort had been rendered defenseless and the army would merely have to walk in and claim it for the Union. “There is not a blade of grass or a piece of stick in that fort that was not burned up,” boasted the admiral.

Butler and his officers begged to differ. Weitzel flatly predicted failure. He had commanded assaults at Port Hudson and other entrenched positions in Virginia and believed the fort’s garrison would make a strong defense despite damage by the naval bombardment. They all agreed that by exploding the powder boat early and beginning the bombardment without the army Porter had compromised the chances of success. Without the element of surprise, landing troops was pointless. Butler was ready to quit and return to Hampton Roads.

By 10:30 the next morning, the fleet was back at battle stations amd unleashing another furious hail of shot and shell. “Broadside followed broadside with great rapidity, and the terrible discharges of the gunboats made one continuous roar, the heavy ordnance making the shores of the Old North State reverberate the deafening roar,” one Union witness reported. It was a harrowing Christmas for the defenders of Fort Fisher. The bombardment tore up the fort’s interior, set the remaining barracks ablaze, and knocked down the garrison flag, but mostly missed the fort’s main works and plunged harmlessly into the river. Lamb continued to restrict his own batteries’ fire, conserving ammunition for the infantry assault he knew was coming soon.

Butler’s Withdrawal

Indeed, the Yankees were coming. About 1:30 pm a few miles north of the fort, the infantry landed unopposed. As the longboats headed for the beach, the fleet increased its fire, pounding the fort and shredding the wooded shoreline at the landing site with a hail of iron. Soon 2,500 troops were ashore. As they moved off the beach and into the woods, they encountered Confederate skirmishers. The staccato pop of small-arms fire rose over the peninsula. The skirmishers belonged to the 42nd North Carolina Regiment of Hoke’s division; the rest had not yet arrived. Heavily outnumbered and in danger of being flanked, they withdrew, and the Federals continued their unfettered advance toward Fort Fisher’s landward face. Inside the fort, Whiting sent urgent pleas to Bragg in Wilmington to reinforce the fort and order an attack on the enemy rear. Bragg seemed rattled and paralyzed with indecision. At one point, the general’s hands were seen to be trembling. In a stunning display of pessimism, he proposed that Fort Fisher be evacuated and made arrangements for his wife to flee the city by train. Meanwhile, Porter maintained a methodical fire designed to make the defenders keep their heads down.

Weitzel reported his observations to Butler. A military engineer by profession, Weitzel was trained to think defensively, and looking at Fort Fisher through binoculars from 2,200 yards away he saw a giant fortress that was still intact and apparently impregnable, the final 100 yards of ground thickly planted with torpedoes. To make matters worse, Confederate prisoners boasted that Hoke’s veteran division, 6,000 strong, was expected to arrive any moment. Butler weighed his options. Grant had ordered him not to withdraw once his troops had landed, but Weitzel weighed in with a critical opinion—building forts was his profession and he believed Fort Fisher was as strong as Fort Monroe, the giant Federal fortress at Hampton Roads. With the seas becoming angry again amid signs that a new storm was approaching, Butler made his decision. He ordered an immediate withdrawal.

Grant Relieves Butler

That was the last straw for Porter. Beside himself with rage at Butler’s decision, the admiral told Grant that the fort could be taken any time a competent general wanted to take it. The army’s loss of one man drowned and 15 wounded indicated something far less than an all-out effort. With the presidential election over and the war on its downhill slope, Butler no longer needed to be handled with kid gloves. Grant, furious that his direct orders had been disobeyed, relieved Butler of command and sent him home to Massachusetts. Before returning to his hometown of Lowell, the politically connected former senator stopped in Washington, where he sought a hearing from the Joint Congressional Committee on the Conduct of the War. After an exhaustive investigation, the committee voted unanimously to exonerate him from blame. Instead, members commended Butler for having had the presence of mind to call off the assault, thereby saving many lives. Such action, ruled the committee, “was clearly justified” by Porter’s ragged gunnery and inadequate support of troops ashore.

Porter was stung by the criticism. He had thrown 20,271 projectiles weighing 1.25 tons at the fort. Inside Fort Fisher, defenders celebrated. Lamb felt that he had good reason to celebrate—the two-day bombardment and Christmas Day skirmishing had produced a mere 61 casualties—surprisingly light for such a pounding. The garrison’s barracks were in ashes, the fort’s traverses were battered, but only four of the fort’s heavy artillery pieces had been destroyed. The Confederacy’s lifeline to Europe was still open. The next day, two blockade runners slipped into New Inlet and steamed upriver to deliver their precious cargo at Wilmington, where Bragg crowed, “The successful defense of Fort Fisher against one of the most formidable naval armaments of modern times proves that the superiority of land batteries over ships of war has been reestablished by the genius of the engineer.” That engineer, Whiting, was not so sure. Indeed, he was shocked by Bragg’s relaxed mood. Not only did the general plan to return Hoke’s veterans to Virginia, but he also suggested that North Carolina’s governor disband the reserves who had helped defend Fort Fisher. Declining an offer of additional ammunition from Lee, Bragg predicted that the Federals would not return until spring. Whiting, understanding that Fort Fisher had been saved largely because the gale on Christmas night had prevented further enemy landings, expected the enemy to return soon, perhaps with a commander willing to press the issue closer than just pistol-shot of the sand walls.

A Devastating Barrage From Porter’s Flotilla

Whiting was right. On January 13, 1865, two hours before dawn, Porter’s flotilla of 59 warships, including five ironclads mounting 627 guns, closed to within 700 yards of the fort and unleashed a withering, fearfully accurate fire. The unrelenting rain of metal fell at a rate of 115 shells a minute, a total weight of 1.6 tons—or 1,000 pounds for every linear yard of the fort. Butler’s earlier complaints about Porter’s ragged gunnery had struck a nerve, and Porter had taken pains to correct it. In his directive to the fleet he cautioned, “The object is to lodge the shell in the parapets, and tear away the traverses under which the bombproofs are located. A shell now and then exploding over a gun en barbette may have good effect, but there is nothing like lodging a shell before it explodes. Commanders are directed to strictly enjoin their officers and men never to fire at the flag or pole, but to pick out the guns.”

The results were devastating. For a Confederate crouched beneath this deluge it was “beyond description. No language can describe that terrific bombardment.” Peering through his binoculars, Porter could see that his instructions were being followed to the letter. One by one, sometimes two by two, Rebel pieces winked out and fell silent. “Traverses began to disappear,” he noted, “and the southern angle of Fort Fisher commenced to look very dilapidated.” Four hours into the bombardment, the army began to land under newly minted Maj. Gen. Alfred Terry. The new commander stood in stark contrast to Ben Butler. A quiet, mild-mannered man with natural tact, Terry was a seasoned combat commander with a proven record in joint operations. Grant instructed the Yale Law School graduate to cooperate fully with Porter and to regard him as the commander of the operation. By 3 pm, there were 8,897 Federals on the beach, two miles north of the fort. Terry had come to stay, and he emphasized this by digging a stout defensive line across the peninsula, facing north in case Hoke’s division, still camped nearby, tried an attack.

“You and Your Garrison Are to be Sacrificed”

In the end, Terry had nothing to worry about. Bragg had no intention of driving the Yankees into the sea. His mentality was defensive and, in Whiting’s opinion, self-defeating. Bragg believed that nothing could be done to prevent the enemy from landing and that Porter’s guns would rip Hoke to shreds. He incorrectly assumed that he was hopelessly outnumbered. Bragg moved about Wilmington headquarters like a man already defeated, picking out a line to fall back on, relocating arms and ammunition, and preparing for evacuation. Meanwhile, Whiting wanted to take Hoke’s division and hit the Yankees before they could fully organize. Bragg ignored his pleas.

Alarmed and frustrated by Bragg’s defeatism, Whiting stormed out and took a steamer back to Fort Fisher. Arriving at the height of the Union bombardment, Whiting made no attempt to hide his feelings from his friend and protegé, delivering a frank and pessimistic greeting. “Lamb, my boy,” he said, “I have come to share your fate. You and your garrison are to be sacrificed.” The naval bombardment was systematically destroying the fort’s artillery, and the toll of dead and wounded was rising steadily. Lamb tried to maintain slow and deliberate return fire, but the barrage kept the gun crews pinned in their bombproofs for long intervals. Nightfall mercifully brought a slackening of the deluge but not a cessation of fire. At work beyond the surf, the five ironclads threw their projectiles with such deadly effect, Lamb reported, that “we could scarcely gather up and bury our dead without fresh casualties.”

“It Was Sheer Murderous Madness”

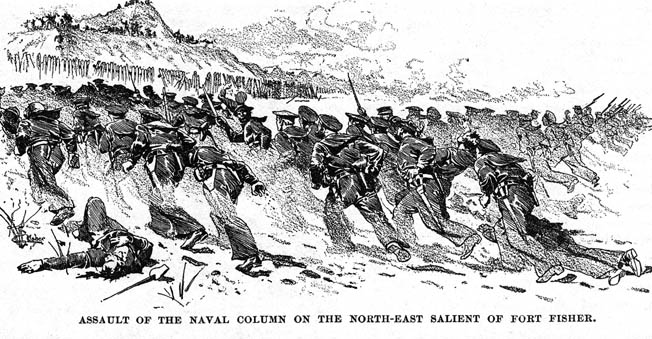

Dawn brought a resumption of the full-scale bombardment, with all the warships back on station. Meanwhile, Terry’s force moved unmolested toward the fort as Lamb’s casualties rose above 200. He now had only 1,550 defenders to face nearly 9,000 battle-hardened Yankees. That night, while the ironclads resumed their nocturnal harassment, Porter and Terry laid plans for the next day’s climax to their joint attack. There was “the most perfect harmony of action” between the two, recorded a witness. The plan was for the fleet to continue its all-out pounding until 3 pm, then cease fire for the assault. Terry would send forward two columns driving down opposite sides of the peninsula, thus avoiding the field of torpedoes north of the fort. On the river flank, half of his command would attack the landface at its western end, while the other half would fix Hoke in position against any possible interference. The ever ambitious Porter was determined that the Navy would be in on the glory. He assembled a naval brigade of 1,600 sailors armed with revolvers and cutlasses and 400 marines carrying carbines to provide covering fire for a boarding action of the seaface. “I will show the soldiers how to do it,” Porter boasted.

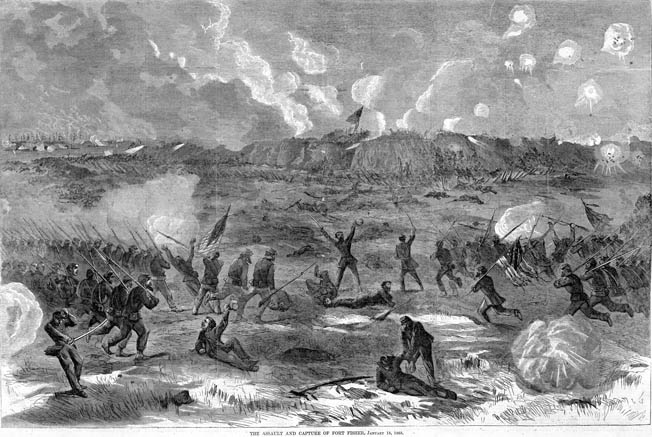

Sunday, January 15, dawned under a bright and cheerful winter sun. Once again the naval bombardment was accurate and effective. The seaface still drew fire from the fleet, but it was concentrated on the landface and the riverside fence. By late morning, Terry had his assaulting division within 500 yards of the landface wall. Whiting continued to press Bragg to attack the Federal rear. “Is Fort Fisher to be besieged, or you to attack? Should like to know,” he demanded. Again Bragg ignored his pleas. As planned, the ships ceased their hellish fire and the naval brigade went forward. The original plan was for them to attack in three waves, but the advance broke down badly and the assault went forward in a single unorganized mass. The sailors made a mad dash up the beach only to be flattened by two volleys of well-aimed musketry. “It was sheer murderous madness,” remembered one observer. They were pinned down, their losses mounting while they dug frantically in the loose sand for cover, then turned and fled up the beach at low tide.

On the fort’s parapet, the Confederates stood and cheered wildly at the backs of the sailors, who left behind more than 300 of their shipmates. However, the attack drew attention away from the riverside fence, where the advance guard of Terry’s first brigade used axes to cut through the palisade and abatis. About the time the defenders were celebrating the repulse of the naval brigade, Terry’s men overran the outer works and stormed the first traverse in a rush. Whiting quickly led a countercharge that retook one of the two lost gun chambers, but he was wounded twice in succession. Lamb arrived with reinforcements. What followed was an old-fashioned donnybrook, a powder-scorched prizefight in which the fighters stood toe to toe, neither side seeking shelter or retreat. The battle was as intimate as it was violent, a free-for-all in the choking heat and smoke. A second Union brigade entered the melee as a brutal struggle raged for possession of the second traverse.

The Fall of Fort Fisher

The attackers seemed to waver and falter—Lamb believed if he could hold on until nightfall he would be able to drive them out. Just then, however, the fleet steamed back into action, shelling the Rebels massed in the rear. The result was “indescribably horrible,” recorded Lamb. Another witness observed starkly, “The air seems darkened with death.” The outnumbered Confederates held their own against the powerful blue tide, fighting ferociously and making them pay for every foot of turf they occupied. Shells from Battery Buchanan were now falling among the Yankees, adding to their hesitancy. Porter’s gunboats were crucial in maintaining Federal momentum. The battle lasted for several more hours, but by 8 pm the landface was lost from end to end and the contest was for the interior. “If there has ever been a longer or more stubborn hand-to-hand encounter,” Lamb declared, “I have failed to meet with it in history.”

Stalled at the third traverse, the Federals appeared indecisive, perhaps even demoralized by the garrison’s stubborn resistance. Lamb believed a determined counterattack would carry the day for the Confederates, but just as he sprang to lead his men forward he was knocked sprawling by a bullet to the hip, and the counterattack fizzled. The defenders yielded ground grudgingly, and Terry threw another brigade against their thinning ranks. As the fight for the last traverse commenced, naval fire along the landface increased, causing great slaughter to friend and foe alike. By now Terry had all four brigades inside the fort, pressing the defenders southward down the seaface, traverse by traverse, until there was nothing left to fall back upon. At 10 pm the flag came down. More than 500 Confederates had fallen in the fort’s defense. Terry lost 955 killed and wounded, Porter 386. “If hell is what it is said to be,” a weary participant wrote, “then the interior of Fort Fisher is a fair comparison. Here and there you see great heaps of human beings laying just as they fell, one upon the other. Some groaning piteously, and asking for water. Others whose mortal career is over, still grasping the weapon they used to so good an effect in life.”

The fall of Fort Fisher brought an end to blockade running and sped the collapse of the Confederacy. Yet again Braxton Bragg had shown an uncanny ability to lose a battle—even when he was many miles away.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments