By Lawrence Weber

As the early days of the Civil War were unfolding and the destiny of the republic was beginning to be contested on the battlefield, Abraham Lincoln was engaged in a no less perilous type of battle. The newly elected president was privately working his way through the dangerous political minefield of slavery, emancipation, and the maintenance of Union loyalty within the border states of Kentucky, Maryland, Missouri, and Delaware. For Lincoln, holding on to these states was of critical importance to the ultimate preservation of the nation itself. In the initial days of the war he observed, “I hope to have God on my side, but I must have Kentucky.” Walking a thin political line between unionists and slaveholders in these states became a primary goal of the Lincoln administration.

Lincoln’s birthplace of Kentucky was arguably the most significant border state. With the secession of Virginia, Tennessee, North Carolina, and Arkansas after the bombardment of Fort Sumter in April 1861, Kentucky played a pivotal role in linking the western border state of Missouri to the eastern border states of Maryland and Delaware. Kentucky also served as a buffer between key Confederate states in the Deep South and the loyal Midwestern states of Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois. Without Kentucky, Missouri would be completely isolated, and vital supply centers such as St. Louis would be much more difficult to maintain while Union forces waged war in the western theater. To lose Kentucky could very well mean losing the war, and Lincoln knew it.

Fort Monroe and the Slave Question

The attack on Fort Sumter did not change Lincoln’s mind about the illegality of secession. On April 19, 1861, he referred to the current situation as “an insurrection against the government of the United States,” not an attack from a foreign nation. He went on to renounce any hostile actions from the seceded states as coming merely from the “pretended authority of such states.” Lincoln was working out a way to classify and eventually destroy the insurrection while also attempting to find a middle ground on the slave question in an effort to placate the border states and ultimately save the Union.

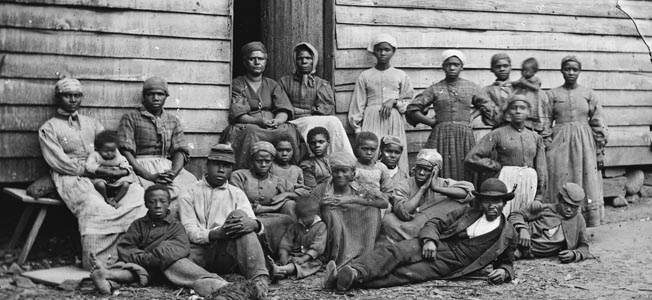

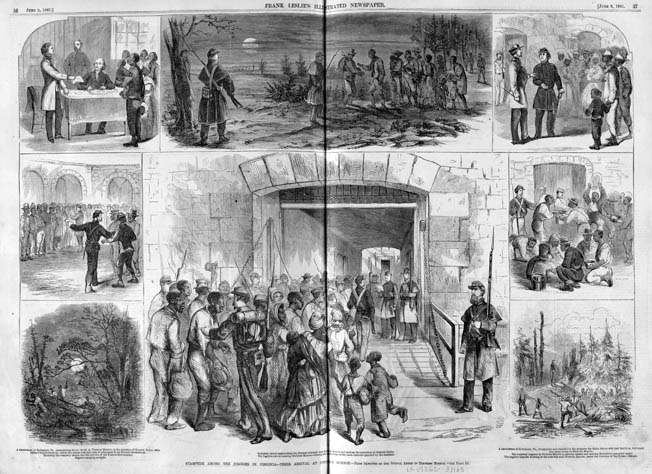

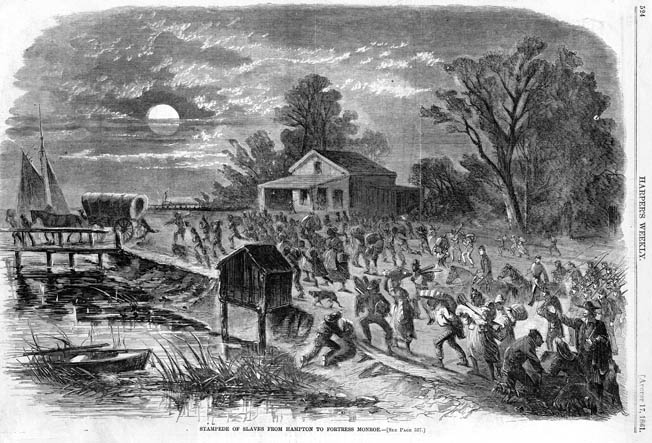

The first real test of the Federal government’s stance on the slave question came at Fort Monroe, Virginia. On May 23, three of Colonel Charles Mallory’s slaves from the 115th Virginia Militia secretly rowed across the James River to Fort Monroe, then in possession of Union soldiers under the command of Maj. Gen. Benjamin Butler. When Butler discovered that the slaves were being used to construct military fortifications in Virginia and were eventually going to be sent to North Carolina to do the same, Butler knew that he needed to make a swift decision on the fate of the runaways.

As Butler pondered his options, Major John B. Cary from the 115th Virginia Militia approached Fort Monroe under a flag of truce to request the return of the fugitives. When Cary urged him to honor his constitutional obligation to return the slaves, Butler responded, “I mean to take Virginia at her word. I am under no constitutional obligations to a foreign country, which Virginia now claims to be.” Pressed further by Cary about the Federal government’s stance of secession as being invalid, Butler replied, “But you say you have seceded, so you cannot consistently claim them. I shall hold these Negroes as contraband of war, since they are engaged in the construction of your battery and are claimed as your property.” Cary abandoned his case and returned to his regiment.

War, Not Emancipation

Butler’s ad hoc contraband policy presented the Lincoln administration with a host of major political problems, the most obvious being that Butler’s policy stood in direct opposition to Lincoln’s recent inaugural address, in which he maintained the illegality of secession. Butler’s policy was going to force Lincoln to reconsider the issue in light of his determination to preserve the loyalty of the border states, where slavery had been firmly entrenched for years. Without addressing Butler’s policy explicitly, Lincoln reminded the general that “the business you are sent upon is war, not emancipation.”

Remaining publicly silent on the issue, Lincoln crafted a special Fourth of July message to Congress in which he defined his belief that the overarching aim of his administration was to preserve the Union. He requested from Congress “the legal means for making this contest a short and decisive one,” including 400,000 men and $400 million. Republican majorities in both houses of Congress increased the appropriations to 500,000 men and $500 million in a clear show of support for the president and his agenda. Conspicuously missing from the discourse was the issue of slavery. Then, on July 21, the Union disaster at First Bull Run occurred.

The Crittenden-Johnson Resolution

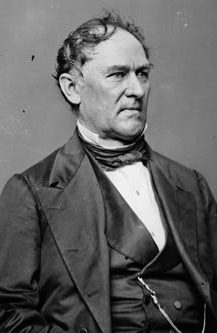

The day after that decisive Union defeat, Lincoln signed a bill authorizing the enlistment of 500,000 men for three years’ service. Three days later, he signed a second bill authorizing another 500,000 men. While a general feeling of despair permeated the North in the days immediately following Bull Run, not everyone had given in to despondency. On July 25, Congress passed the Crittenden-Johnson Resolution, named for its sponsors, Representative John J. Crittenden of Kentucky and Senator Andrew Johnson of Tennessee. The Crittenden-Johnson Resolution, also known as the War Aims Resolution, committed the Union to its original aims of self-preservation and noninterference with slavery. Once again, the government walked a fine line between appeasing the border states and maintaining the Union.

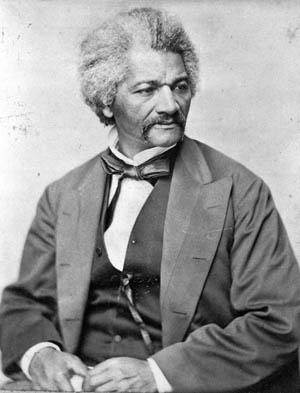

As rumors began to filter into the War Department that slaves were being pressed into service against the Union, the Lincoln administration and Congress began a new debate on what to do about the slave question. Abolitionist (and former slave) Frederick Douglass understood the complexity of the crisis immediately. “War for the destruction of liberty must be met with war for the destruction of slavery,” he said.

More moderate voices attempted to find a middle ground that would strike at the military aspect of slavery while at the same time protect the border states from breaking away.

Crittenden maintained that Congress had no right to legislate on the slave issue. Illinois Senator Lyman Trumbull argued that Congress already was able to punish treason by confiscating property, in effect attacking individual instances of slavery by confiscating slaves who aided the Confederacy during the rebellion, while not attacking the entire institution of slavery.

Lincoln’s Confiscation Act

On July 30, Butler wrote to Secretary of War Simon Cameron, asking him to clarify the status of confiscated slaves at Fort Monroe. “Are these men, women, and children slaves?” Butler wanted to know. “Are they free? What has been the effect of the rebellion and a state of war upon [their] status?” Before Cameron could answer, Congress on August 6 passed the First Confiscation Act, a law designed to “confiscate property [including slaves] utilized for Confederate military purposes and declared that the owner would ‘forfeit his claim’ to any slave so employed.” The Confiscation Act was passed along party lines, with all but six Republicans voting in favor of the act and all but three Democrats voting against it. Lincoln’s bipartisan support for the war was quickly eroding. “This bill,” John J. Crittenden complained, “will be considered as giving an anti-slavery character and application to the war.” Delaware Senator James A. Bayard, a Peace Democrat, advised, “Anything is better than a fruitless, hopeless, unnatural civil war.”

Fearing that the Confiscation Act violated the constitutional right to due process under the law and would further alienate the border states by its antislavery tone, Lincoln nevertheless reluctantly signed the bill into law, bowing to pressure from the bill’s overwhelming Republican support. The Confiscation Act essentially nullified the Crittenden-Johnson Resolution. Preservation of the Union began to take on a divisive antislavery nature, just as Crittenden had predicted and Lincoln had feared.

Two days after the Confiscation Act was signed into law, Cameron responded to Butler’s letter on the status of escaped slaves. Purportedly speaking on behalf of Lincoln, Cameron instructed Butler to follow the provisions of the Confiscation Act in dealing with persons “employed in hostility to the United States.” Much to the eventual chagrin of the president, who was not speaking through his secretary of war, Cameron added, “A more difficult question is presented in respect to persons escaping from the service of loyal masters. Under these circumstances it seems quite clear that the substantial rights of loyal masters will be best protected by receiving such fugitives as well as fugitives from disloyal masters into the service of the United States. Upon the return of peace Congress will doubtless properly provide for all the persons thus received into the service of the Union and for just compensation to loyal masters.” Cameron in essence was extending the Confiscation Act to include fugitive slaves within border states, effectively nullifying the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850.

John C. Frémont: Deciding the Fate of Missouri

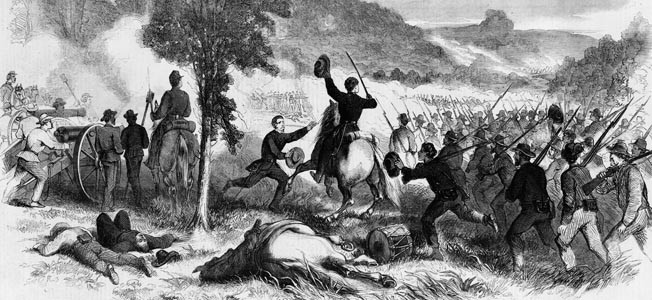

Four days after the passage of the Confiscation Act, on August 10, the first major battle west of the Mississippi River was fought in Missouri at Wilson’s Creek, a 14-mile waterway near Springfield. Union soldiers in the Army of the West, commanded by Brig. Gen. Nathaniel Lyon, clashed with Confederate and Missouri State Guard soldiers commanded by Generals Benjamin McCulloch and Sterling Price. Confederates carried the day after an intense fight that began at first light and lasted for more than five hours, with most of the carnage centering on a ridge soon to be known as “Bloody Hill.” Along with being the first major battle in a border state and the first major battle west of the Mississippi River, the battle was notable for the death of Lyon, the first Union general killed in the Civil War.

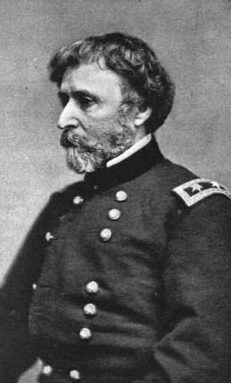

Between the Battle of Wilson’s Creek and the subsequent Battles of Fredericktown and Springfield, which both took place in late October 1861, the fate of Missouri hung in the balance as tension between pro-Unionist, and pro-secessionists flared to alarming levels. With the death of Lyon at Wilson’s Creek, it was up to the Western Department’s commander, Maj. Gen. John C. Frémont, to ensure that Missouri did not descend into anarchy and secession. He seemed imminently qualified to face the challenge. By the time the Civil War began, Frémont was already a household name and national hero, having earned the sobriquet “the Pathfinder” for his western excursions during the 1840s, including several with the noted guide Kit Carson. Frémont’s journeys included an exploration of the South Pass along the Oregon Trail, an expedition through the Sierra Nevada mountain range, a dangerous journey into California during the Mexican War, and a disastrous self-funded journey to the Southwest with the purpose of finding a suitable route for a transcontinental railroad, which ended with the death of 10 members of his party.

By the time he ran for the 1856 presidency as the first candidate of the newly organized Republican Party, Frémont had been military governor of California, one of the first two senators from the new state of California, a famous writer and explorer, and a leading voice for the antislavery platform in national politics. With the election of Lincoln to the presidency in November 1860, it was just a matter of time before Frémont would land a position somewhere in the new Republican administration. On Christmas Day, William Seward wrote to President-elect Lincoln suggesting Frémont for consideration as secretary of war.

Despite Seward’s recommendation, Frémont was never seriously considered by Lincoln for a cabinet position. But in March 1861, Lincoln wrote to Seward asking for his thoughts on Frémont as American minister to France. Seward replied: “Frémont and France—the prestige is good. But I think that is all.” Once again, Frémont was passed over for a position in the Lincoln administration. Finally, on July 3, more than half a year after the initial exchange between Lincoln and Seward, Lincoln asked Seward to assemble the cabinet to “see Gen. Scott, Gen. Cameron, about assigning a position to Gen. Frémont.” The same day, General Order No. 40 was issued creating the Western Department for the Union Army and placing Frémont in command with the rank of major general. Frémont set off to Missouri to bring the tumultuous border state in line with the Union.

Martial Law and Emancipation

Less than three weeks after the Battle of Wilson’s Creek, citing concerns for the public safety in Missouri, Frémont declared martial law in the state “in order to suppress disorders, to maintain as far as now practicable the public peace, and to give security and protection to the persons and property of loyal citizens.” That was all well and good, but what he said next threatened the entire course of the war. “The property, real and personal, of all persons in the State of Missouri who shall take up arms against the United States, and who shall be directly proven to have taken an active part with their enemies in the field, is declared to be confiscated to the public use,” Fremont declared, “and their slaves, if any they have, are hereby declared free.”

Frémont’s de facto emancipation proclamation went well beyond both Butler’s contraband policy, which applied only to fugitives, and the Confiscation Act, which dealt with slaves employed for military purposes. The proclamation sent a shockwave through the Union. If the initial military failures at Fort Sumter, Bull Run, and Wilson’s Creek were not enough to pull the states of Maryland, Delaware, Missouri, and Kentucky away from the Union, targeting the institution of slavery within those states might effectively do the trick.

Lincoln’s Letter to Frémont

On September 2, in a letter marked private and confidential, Lincoln addressed Frémont and his proclamation, stating, “Two points in your proclamation of August 30th give me some anxiety.” The first concerned Frémont’s statement that “all persons who shall be taken with arms in their hands within these lines shall be tried by court-martial, and, if found guilty, will be shot.” Lincoln believed that this policy would lead Confederates to “shoot our best men in their hands in retaliation; and so, man for man, indefinitely.” Lincoln ordered Frémont to get presidential authorization before executing any man under the proclamation.

Frémont’s proclamation and its potential impact on the border states, particularly Kentucky, made Lincoln exceedingly anxious. He wrote again to Fremont. “I think there is great danger that the closing paragraph, in relation to the confiscation of property, and the liberating slaves of traitorous owners, will alarm our Southern Union friends, and turn them against us—perhaps ruin our rather fair prospect for Kentucky,” fretted Lincoln. “Allow me therefore to ask, that you will as of your own motion, modify that paragraph so as to conform to the first and fourth sections of the act of Congress, entitled, ‘An act to confiscate property used for insurrectionary purposes,’ approved August 6th, 1861, and a copy of which act I herewith send you. This letter is written in a spirit of caution and not of censure.”

Lincoln and Frémont Sparr in Public

Frémont did not receive Lincoln’s letter in the spirit that Lincoln had intended. The stage was set for an embarrassing public confrontation. When Frémont sent his politically well-connected wife Jessie, the daughter of former Missouri Senator Thomas Hart Benton, to Washington to advocate for the proclamation on his behalf, Lincoln met with her coldly, ultimately dismissing her complaints in a letter that stated, “No impression has been made on my mind against the honor or integrity of Gen. Frémont; and I now enter my protest against being understood as acting in any hostility towards him.”

Responding to the president’s perceived snub of his wife, Frémont coolly wrote: “If upon reflection, your better judgment still decides that I am wrong in the article respecting the liberation of slaves I have to ask that you will openly direct me to make the correction. The implied censure will be received by me as a soldier always should the reprimand of his chief. If I were to retract of my own accord it would imply that I myself thought it wrong and that I had acted without the reflection which the gravity of the point demanded. But I did not do so. I acted with full deliberation and upon the certain conviction that it was a measure right and necessary, and I think so still.”

Fallout from the Frémont proclamation was quick and sharp. Kentucky slaveholder and longtime Lincoln friend Joshua Speed told the president that “Frémont’s order would inspire border slaves to ‘assert their freedom’ and would ‘crush out every vestige of a union party’ in Kentucky.” Kentucky native Robert Anderson of Fort Sumter fame warned the president that unless the Frémont order was rescinded, “Kentucky will be lost to the Union.” These dire warnings, along with the terrible timing of the proclamation itself—just as the Kentucky legislature was voting to abandon neutrality in favor of Union—prompted Lincoln to act more definitively on the slave issue.

Lincoln’s response to Frémont’s letter was swift and explicitly direct: “Your answer, just received, expresses the preference on your part, that I should make an open order for the modification, which I very cheerfully do. It is therefore ordered that the said clause of said proclamation be so modified, held, and construed, as to conform to, and not to transcend, the provisions on the same subject contained in the act of Congress entitled ‘An Act to confiscate property used for insurrectionary purposes’ Approved, August 6, 1861; and that said act be published at length with this order.”

Lincoln was acting to save the border states for the Union. While Lincoln detested slavery personally, the preservation of the Union, and not a sweeping move on emancipation, remained the ultimate goal of his administration in 1861. The decision to order Frémont to modify his proclamation was intended to ensure the Union maintenance of the border states, preeminently Kentucky. Unfortunately for Lincoln, most of the members of the Republican Party, and many more average citizens from the Union, did not see it the same way.

A Proclamation That United the North

Republican Congressman George Washington Julian of Indiana wrote, “Frémont’s proclamation stirred and united the people of the North during its ten days of life far more than any other event of the war.” And a Cincinnati citizen writing to Horace Greeley regarding Lincoln’s letter to Frémont said, “If a cheer were hip-hipped for Lincoln there the response would be a groan.” Other dissenters were even harsher. “If it is said that we must consult the border states,” wrote one prominent Connecticut Republican, “permit me to say damn the border states. A Thousand Lincolns cannot stop the people from fighting slavery.”

Everyone from newspaper editors to common citizens, from ministers in the pulpit to high-powered politicians, seemed to be criticizing the president for his response to Frémont, but it was criticism from his close friends that stung Lincoln most sharply. On September 17, he received a letter from his close personal friend, Illinois Senator Orville Hickman Browning, criticizing Lincoln’s response to Frémont and his stance on the slave question. According to Browning, the only way to save the government was to strike a blow against slavery, and Frémont’s proclamation represented the government’s best weapon against the rebellion.

A Response to Browning

On September 22, in a letter marked private and confidential, Lincoln responded to Browning. Clearly surprised by Browning’s letter, Lincoln wrote: “I confess it astonishes me. That you should object to my adhering to a law, which you had assisted in making, and presented to me, less than a month before, is odd enough.” Lincoln went on to say that he felt the Frémont stance on slavery and emancipation was “purely political, and not within the range of military law, or necessity.” Elaborating on the rule of law, Lincoln added, “If the General needs them, he can seize them, and use them; but when the need is past, it is not for him to fix their permanent future condition. This must be settled by law-makers, and not by military proclamations. The proclamation in the point in question is simply dictatorship.”

Lincoln then addressed Browning’s position that the Frémont proclamation on emancipation was the only way to save the government. “But I cannot assume this reckless position; nor allow others to assume it on my responsibility,” wrote Lincoln. “You speak of it as being the only means of saving the government. On the contrary it is itself the surrender of the government.”

A careful reading of Lincoln’s letter to Browning shows the president methodically working his way through the legalities of emancipation, Union war objectives, presidential war powers, and border state political strategy. In this early stage of his presidency, Lincoln did not feel that he could permanently emancipate slaves, nor did he think that his role as commander-in-chief allowed him the power to extend permanent emancipation to slaves through his military commanders. “What I object to, is, that I as President, shall expressly or impliedly seize and exercise the permanent legislative functions of the government.” Lincoln’s response to Browning highlighted the fact that Lincoln was truly conservative regarding the possibility of emancipation and that his primary focus during the early months of the war was always the preservation of the Union.

Since preservation of the Union represented Lincoln’s highest objective, maintenance of the border states and not emancipation of the slaves remained his chief war objective. No border state was more important to Lincoln than Kentucky, and in Lincoln’s response to Browning, he explicitly stated that. “I think to lose Kentucky is nearly the same as to lose the whole game. Kentucky gone, we can not hold Missouri, nor, as I think, Maryland,” said the president. “These all against us, and the job on our hands is too large for us. We would as well consent to separation at once, including the surrender of this capital.”

“Frémont’s Pets”

Back in Missouri, Frémont continued to stew, bombarding Washington with demands that he be given a vote of confidence for his actions. “I want the Secretary of War to put an end to the kind of action which is impeding me by producing want of confidence,” he told Jessie Frémont. He complained that Adjutant General Lorenzo Thomas, then visiting Frémont’s Missouri headquarters, was “not friendly to me, and therefore I have a right to demand that he be at once removed from my department. I think that he has been purposely sent with the object that being unfriendly, he would embarrass me. I ought not to have impediments.” When Thomas removed several of Frémont’s subordinates without clearing it first with Frémont, the Pathfinder exploded: “General Thomas is my enemy. He is one of those who opposed my appointment, and I am told indulged in some of the abusive and false language which a certain class about Washington has habitually permitted to themselves in reference to me.”

Surrounding himself with a handpicked personal bodyguard of mostly European officers led by Hungarian Major Charles Zagonyi, Frémont governed like a potentate. “I doubt whether there was as much difficulty and ceremony displayed in gaining an audience with any emperor or king as there was in order to be ushered into the presence of General Frémont,” one visitor complained. Other soldiers in the army took to calling the elaborately uniformed bodyguard “Frémont’s Pets” and the “Kid Glove Brigade.” Frémont’s 10-year-old son, Charley, was given a special cut-down uniform and named an honorary member of the unit. He even drilled with the troops. When Quartermaster General Montgomery C. Meigs and Postmaster General Montgomery Blair went to Missouri to look into complaints that Fremont was dealing with fraudulent or incompetent arms suppliers, Frémont’s bodyguard denied them admission to his headquarters.

The End of Frémont’s Reign

Frémont’s arrest of Congressman Frank Blair for “insidious and dishonorable efforts to bring my authority into contempt with the government, and to undermine my influence as an officer” created another political headache for Lincoln, as did rumors that Frémont was abusing opium. The general’s subsequent arrest of the editor of the influential St. Louis Evening News for daring to criticize Frémont’s military decisions was the last straw. On November 2, Lincoln removed Fremont from command and replaced him with Maj. Gen. David Hunter. Ironically, Hunter would later issue his own unilateral emancipation proclamation while serving as commander of the Department of the South in May 1862, leading Lincoln to remove yet another high-handed general from command.

Frémont was transferred to West Virginia and given command of the newly created Mountain Department, but had the bad luck to go up against Confederate Maj. Gen. Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson during Jackson’s fabled Shenandoah Valley campaign. After losing to Jackson at the Battle of Cross Keys, Frémont was replaced by his subordinate, Maj. Gen. John Pope. He immediately resigned. His war was over.

Frémont’s Legacy

After the Civil War, Frémont eventually retired to New York, but several poor financial investments involving railroads left his family all but destitute. In 1878, a sympathetic President Rutherford B. Hayes appointed Frémont governor of the Arizona Territory, but he resigned from office in 1881 following well-founded charges of dereliction of duty. Frémont spent very little time in the territory he was called upon to govern, preferring to haunt the political corridors in Washington, where he and Jessie devoted much of their time to wining and dining big-money investors for their personal mining and cattle-raising enterprises. Politically and financially ruined, Frémont died in New York City on July 13, 1890, at the age of 77.

Frémont’s historical legacy remains controversial. Gifted with an iron will, a strong moral compass, and an intrepid heart, Frémont was his own worst enemy, often acting with impulsive self-righteousness and without prudence. Frémont truly was a pathfinder in his legendary explorations of the American West, but Lincoln in his way was also a pathfinder. And though Lincoln’s path was more moderate and prudent, reflecting the president’s much greater grasp of political reality and moral suasion, it ultimately proved more successful and far-reaching in the long run. Frémont’s explorations helped expand the American nation. Lincoln’s steely determination held it together.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments