By James A. Davis

Winter was the calmest period for Civil War soldiers. Knowing that there was no combat immediately looming on the horizon allowed the soldiers to relax and recuperate in ways they had not been able to enjoy beafore. There was time for playing games, writing letters, taking naps, and exchanging gossip. For a time, at least, the war seemed far away.

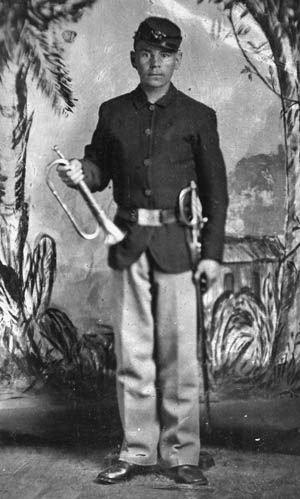

While the men indulged in moments of free time during winter quarters, their daily regimen was still dictated by the army. This meant that the soldiers’ lives were governed by the sounds of the bugles, fifes, and drums that structured the day, and by the sound of drum corps and brass bands that accompanied military ceremonies. Organization was crucial in sustaining and controlling such vast numbers of men. Communication was the backbone of organization, and musicians were at the core of that communication. In Union bugler Oliver Norton’s colorful phrase, field musicians were the “mouthpiece for the general.” Those who had volunteered for the military had placed themselves under the noisy rule of military musicians, and the sound of camp calls and marches became synonymous with their lives as soldiers.

Camp Calls and Skirmish Calls

There were two generic categories of military calls, also known as beats. The first, known as camp calls, were used at specific times of the day to summon soldiers to their duties. These sounded daily whether the men were in camp, garrison, or bivouac. Skirmish calls, on the other hand, governed the martial movements and actions of the troops both in drill and on the battlefield. Camp and skirmish calls could be played by bugle, fife, or drum. In addition, there were short compositions for the drum corps (made up of a unit’s fifes and drums) for primary duties such as reveille.

A camp’s commanding officer designated the specific hours when camp calls were sounded. The first calls began around sunrise, and the final calls occurred by 9 or 10 pm. According to General Order No. 164, 2nd Division, I Corps of the Army of the Potomac, the daily schedule included reveille at daylight, police call 15 minutes later, surgeon’s call at 6 am, breakfast at 7, guard mounting at 8, drill at 9, and recall at 11. Dinner was scheduled for 12:30 pm, followed by more drill at 2, recall at 4, first call for parade 45 minutes before sunset, and second call 15 minutes before sunset. Tattoo was at 8 pm and Taps at 9:20.

The ranking field musician was usually attached to brigade or division headquarters and conferred with the adjutant to set the calls for the day. It was the ranking musician’s responsibility to sound the calls first, which were then echoed in turn by each lower level of musician. The result was a veritable tidal wave of sound that swept over every soldier as well as any unlucky civilians within sounding distance of a camp.

Starting from a single note to eventually encompass hundreds of musicians, with staggered entrances overlapping the tune and different instruments joining in, the resulting music was a vibrant combination of color and chaos. It began with a single drummer or bugler at headquarters, then moved to the principle musicians in each regiment, and climaxed when all the field musicians joined the call. The motion was from a single player to an orchestra of field musicians, from the individual to the group, an aural metaphor of soldier life in the army. The calls of the field musicians gave each army structure and unity of purpose that helped weld the various units into an organic whole.

A Loyalty to Sounds

The literal and figurative mixture of solo and ensemble performances corresponded with the intended audiences for the musicians’ messages. Each field musician was responsible for issuing commands to a limited number of men. A soldier’s primary musical loyalty was to his unit’s musicians, and he took his orders from his company drummer or regimental bugler. Inevitably, musicians from numerous different units would be sounding the same call at the same time, transforming a solo performance into a polyphonic choir of calls. The farther away the listener was from camp, the more the calls merged into a homogeneous wall of sound.

There were two such orchestras present in central Virginia in the winter of 1864, one dressed in blue and other in butternut and gray. Due to the compact nature of winter camp, some soldiers were stationed within hearing distance of the enemy’s camp and could hear their opponents’ daily calls as well as their own. The enemy’s music might draw a certain measure of empathy, as all soldiers could sympathize with the insistent commands that resounded from bugles and drums.

A Shortage of Musicians

Attrition of musicians through sickness, injury, and death severely impacted the functioning of a company or regiment. Competent field musicians required some musical aptitude in addition to military training. It became increasingly difficult to replace experienced field musicians or their instruments as the war progressed. Some companies were forced to do without bugles, drums, or fifes, depending on the fortunes of the unit. While stationed at Gordonsville, William D. Rutherford of the 3rd South Carolina Infantry mentioned that the “drums have just sounded for Dress Parade,” perhaps indicating the absence of fifes or a bugler. George Peyton of the 13th Virginia Infantry recorded in his diary: “Had what they call retreat at sundown. They beat the drums and play a tune or two on a fife.”

Some units were forced to share field musicians; the three companies that made up the 1st Battalion, New York Sharpshooters, were down to two drummers and three fifers in their drum corps by April 1864. These smaller ensembles produced a sparse sound when compared to the full drum corps that so many regiments featured at the start of the war. On the other hand, plenty of musicians and instruments producing a big sound were sure signs of a large and well-provisioned regiment or brigade.

Both large and small groups of musicians had devoted audiences. While a large brigade would take pride in the musical proficiency of its full band or drum corps, a battle-hardened regiment also took pride in its handful of musicians, knowing that their modest sound was a musical reflection of hardships shared and survived.

The Hated Musicians

Because the bugle, fife, and drum controlled the soldiers’ daily lives, the officious notes of the musicians, as well as the musicians themselves, attracted some hostility from the men. After recounting the pain of being woken at 6 am by the braying of a bugle, William Dane, a private in the Richmond Howitzers, complained: “To be waked up and hauled out about day dawn on a cold, wet, dismal morning, and to have to hustle out and stand shivering at roll call, was about the most exasperating item of the soldier’s life. We didn’t kill old Crouch [the bugler]. I don’t know why, except that he was protected by a special providence, which sometimes permits such evil deeds to go unpunished. We used to hope that he would blow his own brains out, through his bugle, but he didn’t—he lived many years after the war.”

Others were less accommodating to the field musicians. Cries of “Put the bugler in the guard house!” or “Shoot the bugler!” greeted many musicians on particularly unpleasant mornings. Such was the disdain for field musicians that they received the questionable honor of having a song written about them. The “Upidee Song” presented a sadistic bugler who took great delight in tormenting his colleagues: “He saw, as in their bunks they lay,/ Tra la la! Tra la la!/How soldiers spent the dawning day./Tra la la la la/‘There’s too much comfort there,’ said he, ‘And so I’ll blow the ‘Reveille.’”

More than the mere disruption of sleep created animus against the musicians. Field calls were synonymous with duty—they were orders that could not be ignored. Field instruments had an intentionally penetrating sound that could be hard to take in terms of music. Those new to the instruments’ timbres found them painfully loud and alarming. The intrusive power of field music lay not only in the raucous nature of the instruments but also in their incessant presence. This was the image Colonel Mason Tyler Whiting of Massachusetts shared with his civilian brother: “If you had to be drummed out to the notes of that infernal drum three or ten times a day, according as it happens, you would growl, I know, when you heard it beat.”

The omnipresent and ferocious sound of fifes, drums and bugles was an indisputable separator between the civilian and soldier worlds coexisting in central Virginia in 1863-64. The constant playing by field musicians was an unavoidable reminder of the perilous reality soldiers now faced and could trigger memories of the gentler life they had left behind. Samuel Potter of Pennsylvania confessed to his wife his desire to be home with her and their children, eating cakes and drinking “catnip tea” while listening to his children sing. “It would sound much better if one of them would call me to dinner or supper than the sound of our bugle making its different calls,” he said wistfully. “You may be sure I would prefer the music of home in its different keys.”

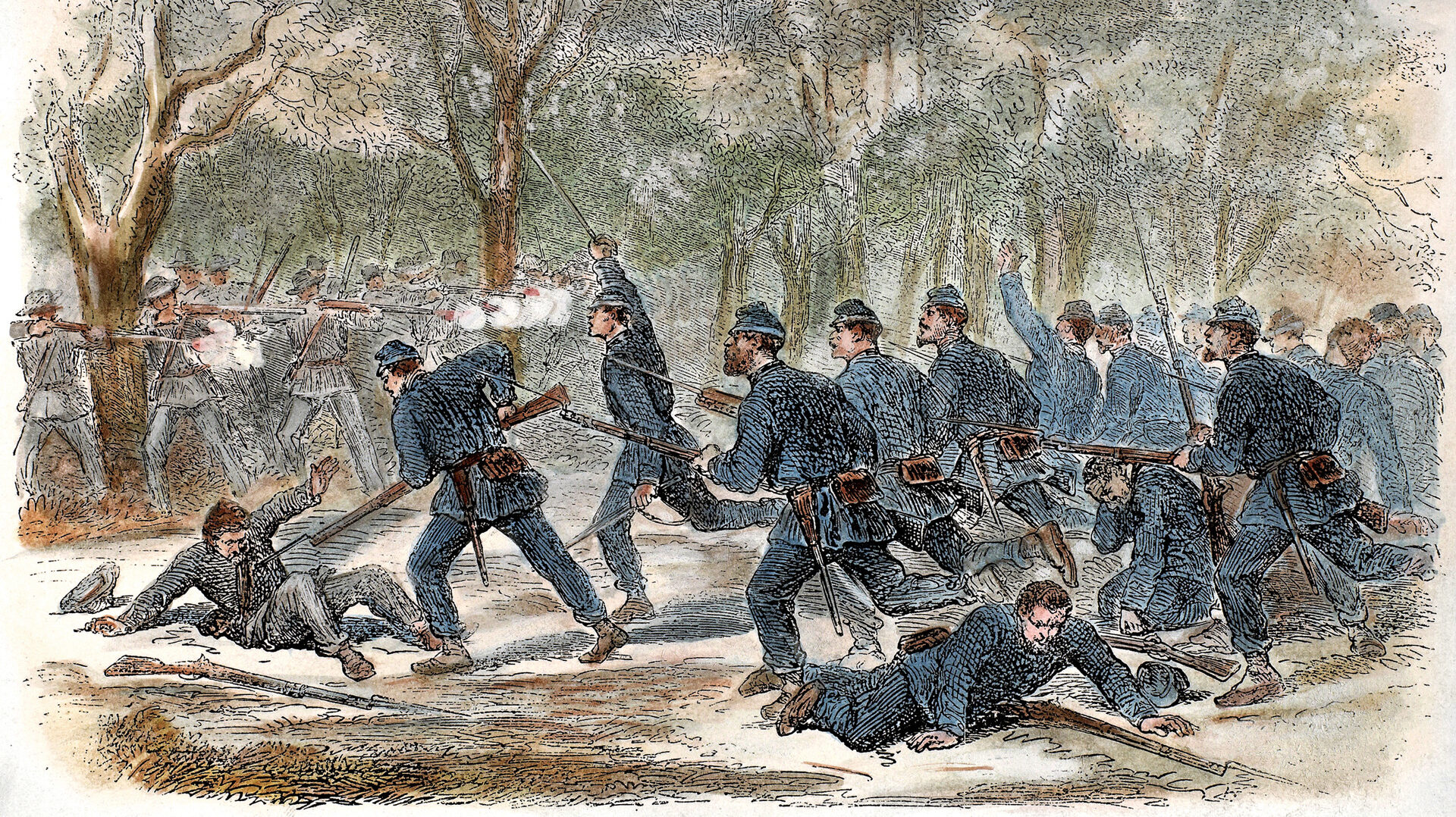

The brash sounds of field musicians stood in opposition to the normal sounds of nature. Before departing for the Battle of the Wilderness, Confederate Maj. Gen. John B. Gordon noted his surroundings near Brandy Station, Virginia, with an eye toward its natural beauty: “There was not a cloud in the sky, and the broad expanse of meadow-lands on the north side of the little river and the steep wooded hills on the other seemed ‘apparelled in celestial light’ as the sun rose upon them.” Gordon’s poetic moment was sadly short lived, as field music intruded into his reverie: “At an early hour, however, the enchantment of the scene was rudely broken by bugles and kettledrums calling Lee’s veterans to strike tents and ‘fall into line.’”

Fondness For a “Pleasant Tattoo”

Not all depictions of field music were negative. Despite its mechanistic functionality, field music was still music and as such could trigger positive responses as well. Gordon, whose meditation on the beauties of nature was so rudely interrupted by the sound of field musicians, could also hear the aesthetic sigh of the music. “A more peaceful scene could scarcely be conceived than that which brought upon our view day after day as the rays of the morning sun fell upon the quiet, wide-spreading Union camp,” he wrote, “with its thousands of smoke columns rising like miniature geysers, its fluttering flags marking, at regular intervals, the different divisions, its stillness unbroken save by an occasional drum-beat and the clear ringing notes of bugles sounding the familiar calls.”

What separated the two contrasting moments for Gordon was less the sound of the instruments themselves than the message they conveyed. Fifer Harry Kieffer recollected the “peculiar charm” that the drum corps gave to dress parade and the “pleasant tattoo at night” performed by he and his fellows. Jefferson Whitcomb of Massachusetts was even willing to toss a compliment to a performer one pleasant day in April: “Cleaned up round the camp. Bugler very nice.”

There was something about the music from field musicians that appealed to the soldiers aside from any specific messages the music conveyed. When remembering the attractions of soldier life, Captain Samuel Craig of Pennsylvania included the musical sounds of the morning. The bugles were “sweet,” the fifes were “shrill,” and the drums “loud,” but somehow they generated a certain fondness as much as they irritated. Ted Barclay, a member of the 4th Virginia Infantry, included field music when answering his sister’s concerns for his situation in camp in Orange County, Virginia: “We have a great many friendships of which homefolks are deprived of, for instance you cannot get around one oven in the sociable way and eat your meals, neither are your ears charmed with the rattle of the fife and drum, etc., etc. A soldier is after all not so much to be pitied as you would suppose.” Barclay’s view was shared by Charles George of the 10th Vermont, who admitted his grudging attachment to the sound: “The drum Corps is just beating out tattoo—I think I shall miss the drums when this cruel war is over!”

John Esten Cooke was even more inclined to respond positively to field music. The sentimental novelist of the Confederacy was prone to poeticize most of what he saw around him, as seen in his description of the sound of a bugle: “The tattoo, reveille, and stable-call have echoed through the pine woods, making cheerful music in the short, dull days, and the winter nights. It is singular how far you can hear a bugle-note. That one is victor over space, and sends its martial peal through the forest for miles around. There is something in this species of music unlike all others. It sounds the call to combat always to my ears; and speaks of charging squadrons, and the clash of sabres, mingled with the sharp ring of the carbine. But what I hear now is only the stable-call. They have set it to music; and I once heard the daughter of a cavalry officer play it on the piano—a gay little waltz, and merry enough to set the feet of maidens and young men in motion.”

A Call For “Us”, Not “I”

The repetitious and orderly nature of camp calls was one of the most obvious ways in which the army imposed its collective will on the social, temporal, and physical environment of the men during winter camp. Field music reminded each soldier that he was a part of a company or regiment and structured his environment. The calls were meant for “us,” not “I.” The music unified the army as a whole, and the longer the armies stayed in one place, the more stability accrued. It was as if there were one language spoken by the men, said Union veteran Ira Dodds, “The voice of the comradeship of a mighty, invisible host.”

Reveille, Tattoo, Taps—each held significant meaning for the soldiers whose lives were now ruled by the sound of field musicians. For the men in uniform, the pieces were an intrinsic part of their new lives, an obtrusive yet necessary voice of the military machine. For better or worse, the sounds of fifes, drums, and bugles became synonymous with their lives as soldiers, symbolizing their years of service as well as the lasting bonds of comradeship that developed between them. For soldiers in both armies, waking every morning to the piercing cry of bugles and the thundering of drums was a potent reminder that the war was always with them, no matter how well they might have slept the night before.

As a company bugler for a CW reenactor unit, I am impressed with the insights of the writer of this piece, James Davis, as well as his style.

There is a nuance and depth here not often encountered in brief articles about bugles, fifes and drums in the Civil War military.

Well done!

F. Dorritie

Bugler, Co G, 20th Maine Vol Inf