By Mike Phifer

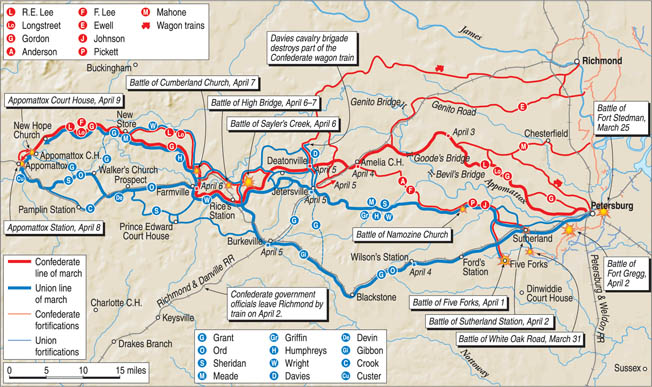

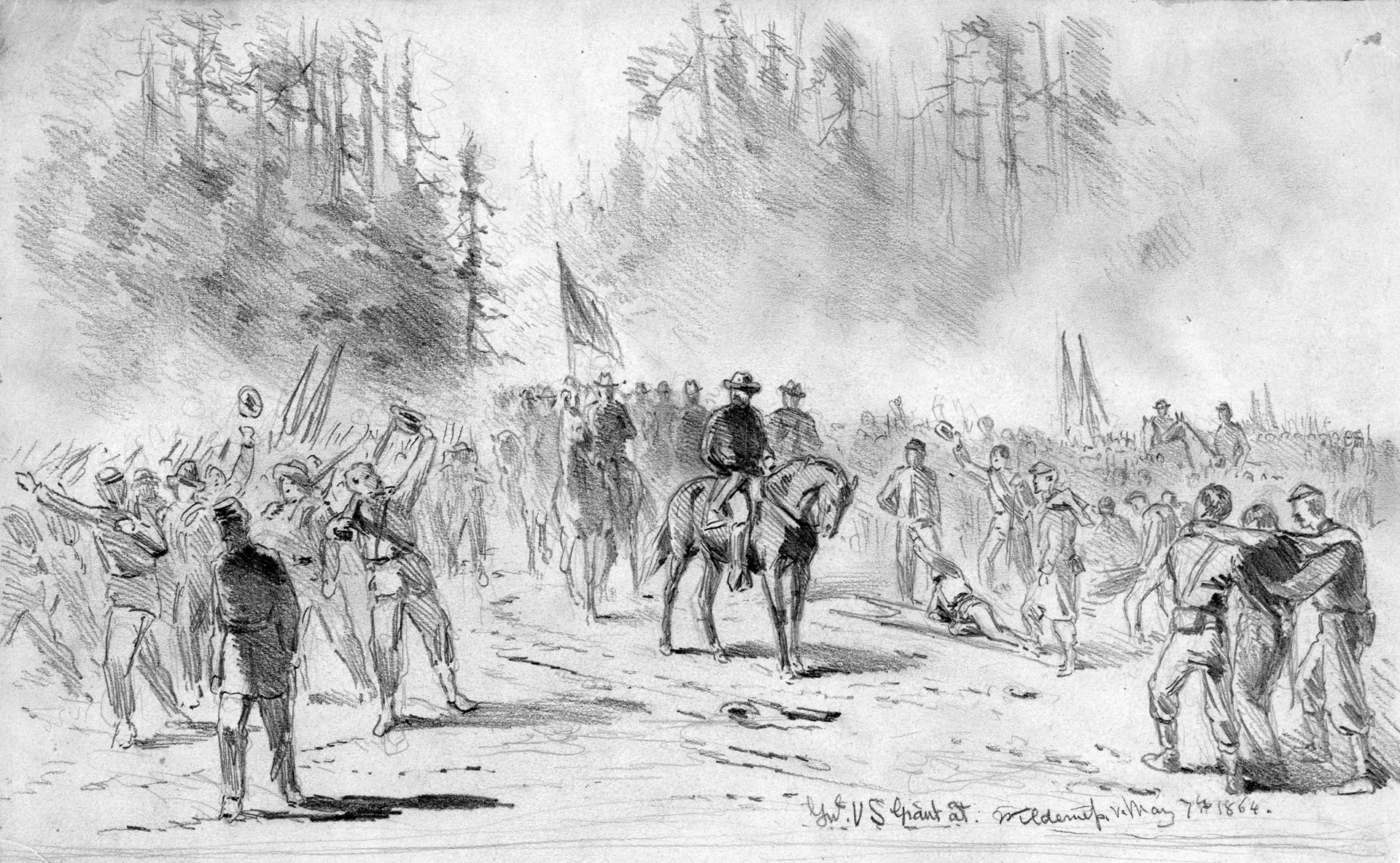

Lieutenant Colonel Horace Porter, personal aide to Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, maneuvered his mount past ammunition wagons, ambulances, stragglers, and prisoners jamming the muddy roads leading back to headquarters from Five Forks, Virginia, on the evening of April 1, 1865. A great victory had just been won at Five Forks by Federal forces under Maj. Gen. Phil Sheridan. To Porter it seemed like “the beginning of the end.” Four years of unrelenting war were drawing to a close. Reaching headquarters, Porter began shouting the good news to Grant and the rest of his staff, who were sitting in front of the general’s tent enjoying the warmth of a crackling campfire.

Porter dismounted and gave Grant more precise details of the victory. After listening intently to the report, Grant turned and disappeared into his tent. He returned shortly afterward with several dispatches that he handed to orderlies to be telegraphed over field wires. Grant then walked over to the campfire where Porter had joined the other staff officers and calmly announced, “I have ordered a general assault along the lines.” The campaign to end the war in Virginia would commence at 4 o’clock the next morning.

Grant’s Siege of Petersburg

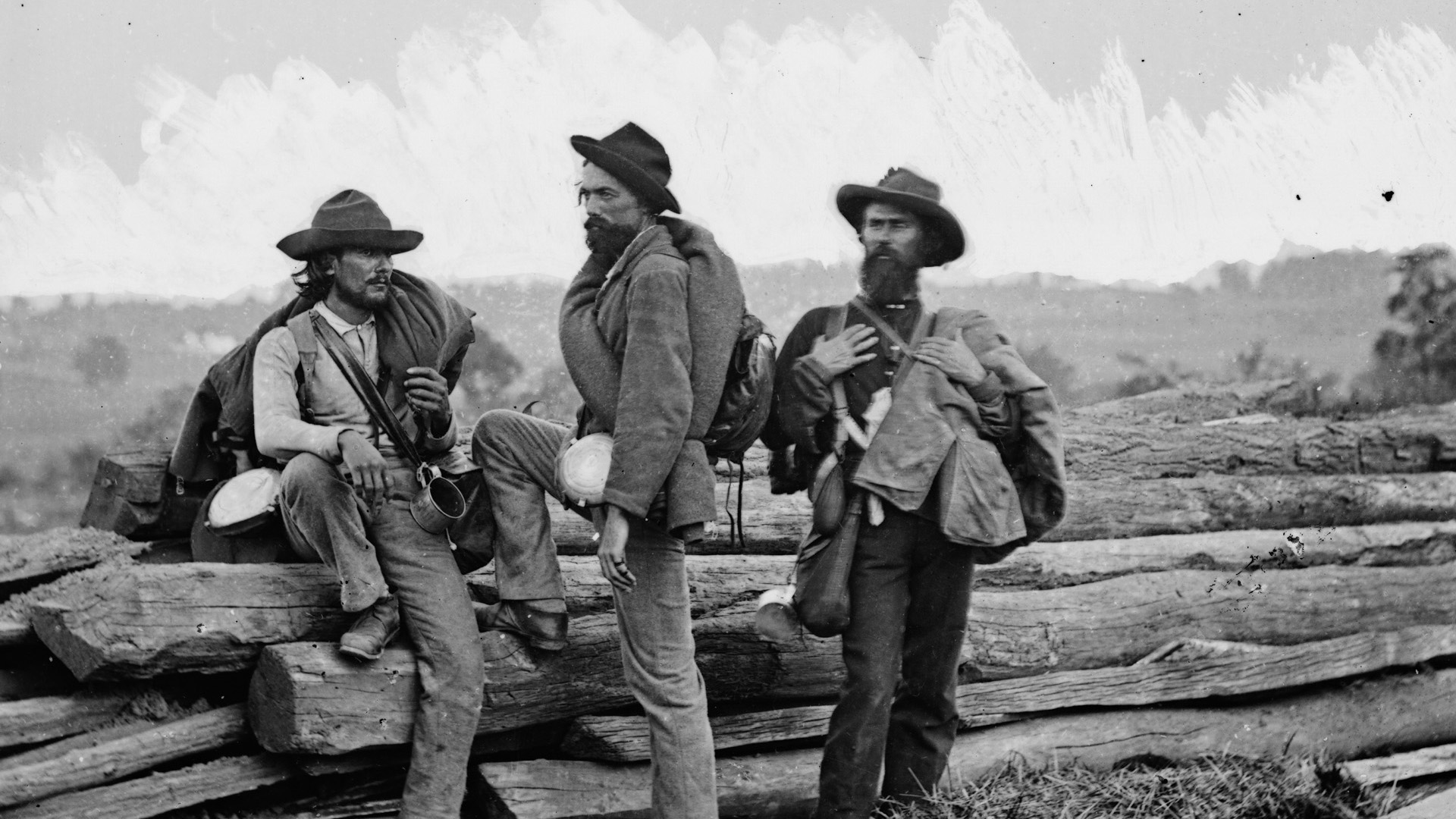

For the last 10 bloody months, Grant, as general in chief of all Union forces, had personally directed operations for the Army of the Potomac and the Army of the James, locked in a grueling siege with the Army of Northern Virginia around Petersburg. More than 30 miles of trenches and redoubts stretched east of Richmond, skipping over the James and Appomattox Rivers around Petersburg and ending six miles southwest of the city at Hatcher’s Run. Some 42,000 bluecoats had been killed or wounded as Grant unsuccessfully tried to break the Confederate lines. With the coming of spring, Grant feared that Confederate General Robert E. Lee would attempt to slip his army west out of the tightening Federal lines at Petersburg and head south to join General Joseph Johnston’s battered Confederate forces at Raleigh, North Carolina. If such a junction took place, Grant worried, “a long and tedious and expensive campaign consuming most of the summer might be inevitable.”

At 10 pm on April 1, following Grant’s orders, the Federal artillery opened up. “From hundreds of cannons, field guns and mortars came a stream of living fire as the shells screamed through the air in a semi-circle of flame, the noise was almost deafening,” wrote Sergeant Joseph Gould of the 48th Pennsylvania. “The bombardment grew furious as it increased along the whole line, from north of Petersburg to Hatcher’s Run.”

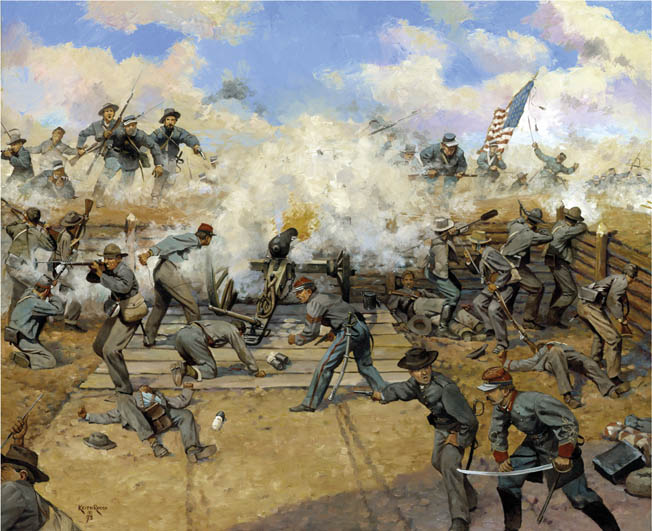

The Federal artillerymen continued to hammer the Confederate trenches early the next morning, while the infantrymen prepared to attack. At 4:30 am, Maj. Gen. John Parke’s IX Corps attacked the trenches east of Petersburg, including the Confederate stronghold, Fort Mahone. Despite taking deadly volleys of bullets, grapeshot, and canister, the bluecoats pushed on, struggling through the water-filled ditch in front of the earthworks and fighting their way into the enemy defenses, capturing batteries, redans, two forts, and trenches. The Confederates continued to hang on to the inner defenses, and fierce fighting raged throughout the day as Maj. Gen. John Gordon’s division launched desperate counterattacks. Federal reinforcements arrived later in the day to help secure Parke’s shaky hold.

Simultaneously, Maj. Gen. Horatio Wright’s VI Corps, with its three divisions arranged in a wedge-shaped formation, attacked Lt. Gen. A.P. Hill’s corps on the Boydston Plank Road at 4:40 am. The forward Confederate rifle pits were overrun as the Federals surged toward the enemy entrenchment, leaping across the ditch in front of it. Colonel Elisha Rhodes of the 2nd Rhode Island Volunteers would later recall, “We scrambled and helped each other up the slope of the work and stepped upon the parapet amid the guns of the enemy, who fled to the rear. After firing our volley we jumped into the rebel works and gradually forced the enemy to leave the cover of their huts, from behind which they were firing.”

After 20 minutes of savage fighting, the Federal troops smashed through Brig. Gen. James Lane’s brigade of Maj. Gen. Cadmus Wilcox’s division and tore a hole in the Confederate line. VI Corps regrouped and pushed on toward the Southside Railroad, while part of the corps split off to roll up the rest of Hill’s line at Hatcher’s Run.

Lee’s Intention to Withdraw

From his headquarters at Turnbull House, Robert E. Lee was meeting with Hill and Lt. Gen. James Longstreet, who had brought part of his corps south of the James River the day before, when word arrived of the Union breakthrough. Hill quickly mounted up and rode out with another officer and two couriers to rally his troops. He did not make it. En route, Hill was shot and killed by two soldiers of the 138th Pennsylvania.

There was no time to mourn Hill’s death. Lee sent a message over the telegraph line at 10 am to Secretary of War John Breckinridge, warning, “I see no prospect of doing more than holding our position here until night. I am not certain I can do that. If I can I shall withdraw tonight north of the Appomattox, and, if possible, it will be better to withdraw the whole line to-night from James River. I advise that all preparation be made for leaving Richmond tonight.” The doleful message was rushed to President Jefferson Davis, who was in church at the time.

Meanwhile, Maj. Gen. Henry Heth led a couple of brigades from his own and Wilcox’s divisions west along the Southside Road to Sutherland Station, where he located a wagon train loaded with supplies. Heth determined to make a stand to buy time for the wagons to escape. He positioned his 3,000-man force on a ridge behind some hastily erected breastworks of fence rails. After hearing of Hill’s death, Heth left Brig. Gen. John Cooke in charge and made his way back to Petersburg to assume command of what was left of the corps.

Around 11 am, another ridge about half a mile away began “to glitter with arms, and then to grow blue with the long lines of the enemy swarming to the attack,” wrote Captain James Caldwell of Brig. Gen. Samuel McGowan’s brigade. The bluecoats were the lead brigade of Maj. Gen. Nelson Miles’s division of the Army of the Potomac’s II Corps. They surged forward, not halting to dress their lines, observed Caldwell, “but with yells of mingled confidence and ferocity, they rushed forward rapidly, disordering their line and breaking through all control.”

The attackers were met with artillery fire but charged on, pushing closer to the Confederates’ works. The crash of the volleys and the roar of shouting filled the air as both sides traded fire. The Federals fell back but attempted a second attack when another brigade arrived. This attack was also driven back. Finally, a third brigade was brought up and used in a flank attack that scattered the defenders. The Southside Railroad was cut.

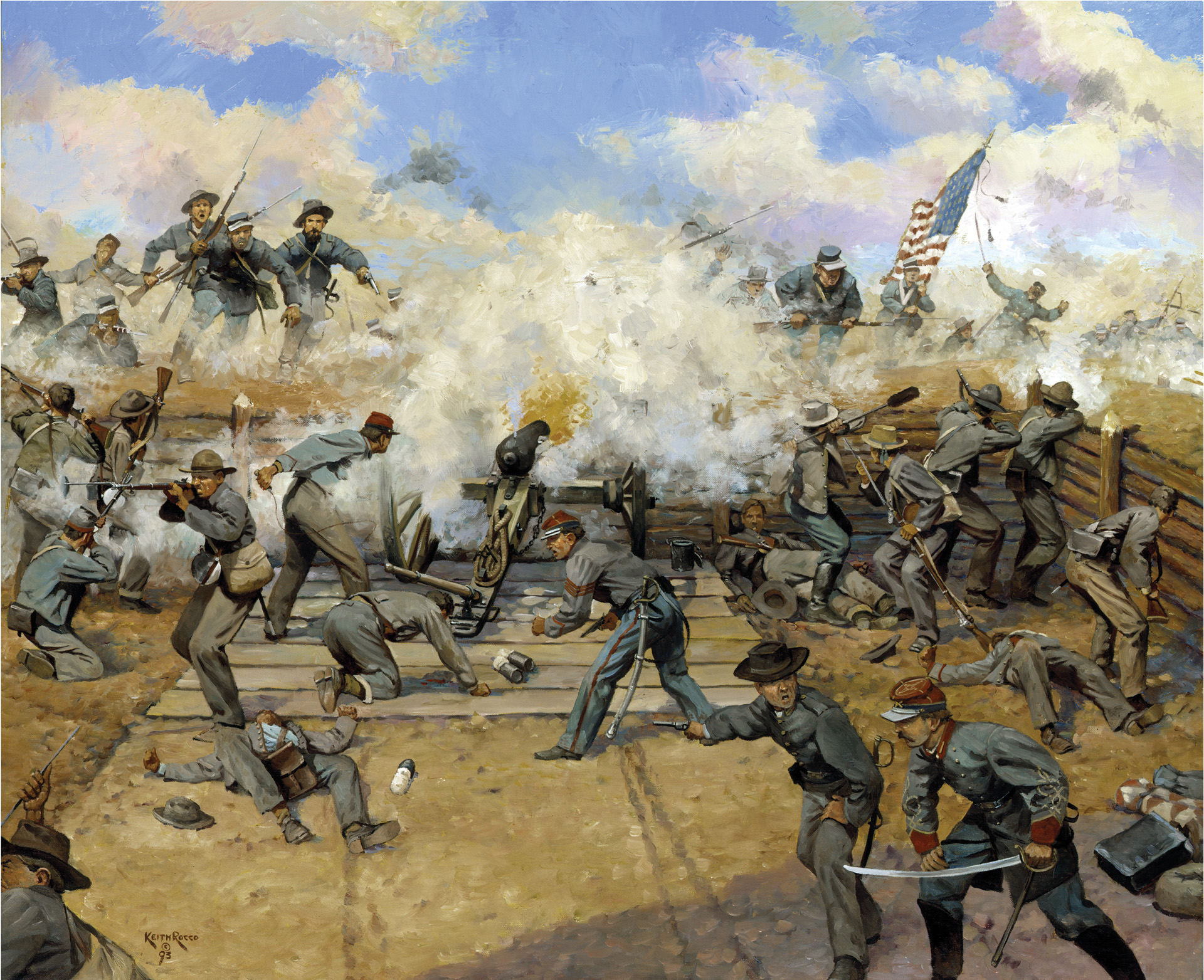

The Fall of Fort Gregg

While this was going on, Brig. Gen. Nathaniel Harris’s brigade of Mississippians in Maj. Gen. William Mahone’s division and 25 artillerymen from Washington Battalion, Louisiana Artillery were taking up positions in Fort Gregg and Fort Whitworth, four miles west of Petersburg. The 12th and 16th Mississippi Regiments and two guns holding Fort Gregg were soon facing two divisions of Maj. Gen. John Gibbon’s XXIV Corps of the Army of the James. Federal artillery opened up on both forts, and the plucky Confederates answered back.

At 1 pm, the two Union divisions, joined by comrades from VI Corps, attacked the heavily outnumbered Confederates. The Federals centered the bulk of the attack on Fort Gregg, where roughly 200 defenders fought back ferociously. Despite their bravery, the small band of Mississippians could not hold off the Federals, who eventually fought their way into the fort. Brutal hand-to-hand fighting raged. At 2:30 pm, the surviving Confederates in Fort Gregg surrendered. With the capture of Fort Gregg, the Confederates defending Fort Whitworth were now outflanked, and they quickly abandoned the fort. Still, the defenders of Fort Gregg had bought enough time for part of Longstreet’s corps to move into the innermost earthworks protecting Petersburg.

The Evacuation of Richmond

While the exhausted, victorious Federal troops halted their attack to rest, the evacuation of Richmond began at 8 pm. The Confederate troops retreating from both the Petersburg and Richmond fronts were to rendezvous at Amelia Court House, 40 miles to the west, where tons of rations were supposed to be waiting for them. From there Lee planned to retreat south down the Richmond & Danville Railroad to join Johnston in North Carolina.

Lieutenant General Richard Ewell led the troops defending Richmond out of the city. The erstwhile defenders, including Maj. Gen. George Washington Custis Lee’s division, crossed the James River and headed for the ruined Genito Bridge, where they were to cross the Appomattox River on a pontoon bridge and continue on to Amelia Court House. Traveling with Custis Lee was a large wagon train and about 200 light artillery pieces that would cross the river near Meadville. Mahone, meanwhile, pulled his troops out of the trenches near Bermuda Hundred and headed for Goode’s Bridge over the Appomattox.

Gordon’s, Hill’s, and Longstreet’s corps crossed over bridges to the north side of the Appomattox before turning west. Maj. Gen. George Pickett’s battered troops, Maj. Gen. Fitzhugh Lee’s cavalry, and Maj. Gen. Bushrod Johnson’s men, under the overall command of Lt. Gen. Richard H. Anderson, headed for the court house as well. A single train steamed out of Richmond for Danville carrying President Davis, his cabinet, government documents, and all the gold that was left in the treasury.

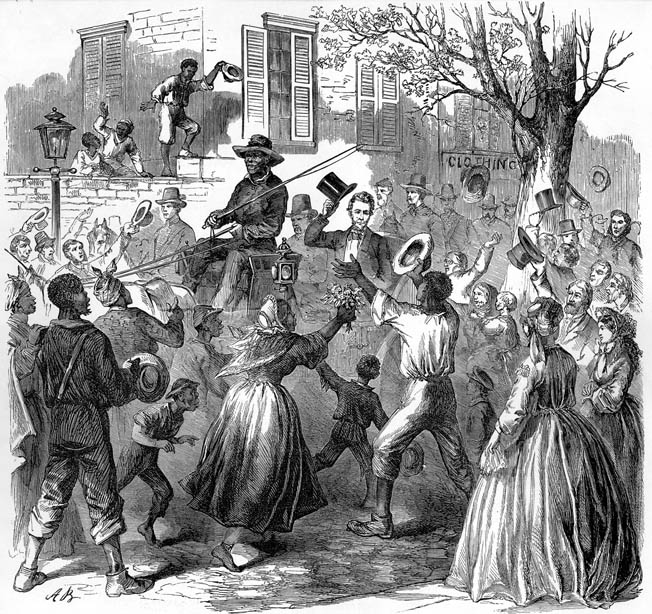

As the Confederates were pulling out of Petersburg, warehouses filled with military supplies were being torched, lighting up the darkness. In Richmond the flames from warehouses and foundries quickly spread, engulfing hotels, banks, and government buildings. Soon nearly 800 buildings were on fire in the city. Making matters worse, angry mobs began “besieging the commissary stores, destroying liquor, intent perhaps upon pillage, and swaying to and fro in whatever momentary passion possessed them,” reported a local newspaper editor. Shortly after dawn on April 3, Union troops moved into Richmond and Petersburg.

Cutting the Confederates off at Burkeville Junction

Grant assumed that Lee would retreat along the Richmond & Danville Railroad to North Carolina. He determined to cut off the Confederate army at Burkeville Junction rather than pursuing it across the open countryside. Before leaving, Grant met briefly with President Abraham Lincoln, who was waiting nearby to enter the Confederate capital. The next day Lincoln would make a triumphant entry into Richmond, where he would be greeted excitedly by former slaves as he made his way to visit the Confederate White House and Libby Prison, among other places of note. Most of the remaining citizens stayed closeted behind locked doors while the president toured the fallen capital.

Lee’s retreating columns had to cross the Appomattox River, which proved difficult due to spring floods. Longstreet’s and Gordon’s corps were originally supposed to cross the river at Bevil’s Bridge, but it was flooded. They were ordered to proceed farther north to cross at Goode’s Bridge, where Mahone was also scheduled to cross along with Gordon’s wagons. Getting so many troops across the river ate up precious time. By nightfall most of Longstreet’s troops were encamped on the west side of the bridge, while Gordon’s and Mahone’s men bedded down on the east side.

Anderson and Fitzhugh Lee had been sparring with Sheridan’s troopers all day. The Federal II Corps and the V Corps, under the command of Maj. Gen. Charles Griffin, marched for Danville, while VI Corps pushed west as well. IX Corps temporarily stayed behind to secure Petersburg. Maj. Gen. E.O.C. Ord with three divisions from the Army of the James marched for Burkeville Junction, paralleling the Southside Railroad as they went.

Leading the Federal cavalry’s pursuit was Maj. Gen. George Custer’s 3rd Division. In the early morning, Custer arrived at Namozine Creek to find Brig. Gen. William Roberts’s brigade of North Carolinians acting as the rear guard for Anderson on the west bank. Custer quickly brought up a battery, and while the gunners fired canister at the enemy the 1st Vermont Cavalry forded the creek and struck Roberts’s troops in flank, causing them to retreat.

Five miles farther west, at Namozine Church, Brig. Gen. Rufus Barringer’s brigade of North Carolinians took over as rear guard for Anderson’s column. Barringer’s 800 troopers of the 1st, 2nd, and 5th North Carolina Regiments were positioned at the intersection of the church and the road. The 8th New York Cavalry, leading Custer’s division, probed the Confederate position before falling back to be joined by 1st Vermont. The two Union regiments then attacked, with the 8th New York attempting to hit the Rebels’ left flank. The 2nd North Carolina was ordered to countercharge the New Yorkers, but to no avail. The 1st North Carolina broke first, and after the arrival of the 15th New York, Barringer’s troopers gave way completely, with many of the men surrendering. Custer bagged 350 prisoners, including Barringer. In all, Sheridan’s forces had taken about 1,200 prisoners, most of them from Heth’s and Wilcox’s brigades, which had escaped the fight at Sutherland Station the day before.

Attack on Ewell’s Wagon Train

In the early morning hours of April 4, the Confederate troops at Goode’s Bridge continued to cross and march toward Amelia Court House, 8½ miles to the west. Robert E. Lee, riding with Longstreet, moved on to Amelia Court House, where to his bitter disappointment he discovered that the boxcars waiting for him carried no rations. Lee had intended to stay at Amelia Court House just long enough to feed his troops, but now he would need more time to gather food for his army. Lee issued a formal proclamation to local residents requesting provisions, while he also called for 200,000 rations to be sent by train to Danville.

Sheridan, following closely, sent Maj. Gen. George Crook’s 2nd Division of cavalry and the V Corps infantry to Jetersville Station. He was convinced that Lee would have to pass through Jetersville on his retreat to Danville. Sheridan had his men dig in, ready to block Lee’s army. Meanwhile, unable to cross the river at Genito, Ewell pushed south to Mattoax Station, where the Richmond & Danville Railroad crossed the Appomattox. Ewell’s men put planks over the rails and crossed over to the west side of the river, where they camped for the night. Fitzhugh Lee’s and Anderson’s commands broke off skirmishing with Sheridan’s cavalry and bedded down at the junction of Bevil’s Bridge and Tabernacle Church Roads, southeast of Amelia Court House.

Rain greeted both armies on the morning of April 5. The separate Confederate columns continued on toward Amelia Court House, where largely empty quartermaster wagons began rolling back into the settlement, not having had much success in procuring food from local residents. Lee ordered the supply wagons and batteries trimmed down, with the best horses and mules going to the artillery and the wagons accompanying the troops. Extraneous caissons were taken out of town and destroyed, and artillerymen now found themselves serving as infantry.

The wagon train traveling separately from Ewell’s column had crossed the Appomattox River and was only about four miles from Amelia Court House when Brig. Gen. Henry Davies’s Union brigade struck. The Confederate gunners attempted to get their weapons into action, but the Federal cavalry were on them with sabers flashing before they could fire. Some of train guard scattered, but Davies captured another 630 troops and torched 200 wagons full of ammunition and provisions.

Word of the disaster quickly reached Robert E. Lee, who sent the bulk of his cavalry galloping along the muddy roads in pursuit. Fitzhugh Lee’s troopers pushed past the burning wagons and came upon Brig. Gen. Martin Gary’s brigade of Confederate horsemen battling the Federals. A running fight ensued as the Southern horsemen pushed the Federals to within a mile of Jetersville. The rest of Crook’s division came to the aid of Davies’s men, but not before 30 lay dead and another 150 had been wounded and captured.

Two Regiments Lost at Farmville

Around 1 pm, Lee’s army left Amelia Court House and headed southwest. Lee again rode with Longstreet, the cavalry leading the way. Lee decided to shift his retreat, having his spread-out army march north of the Federals’ left flank and head for Farmville, where 80,000 rations were said to be waiting for his hungry troops. Captured reports revealed that Grant was at Jetersville and Ord was at Burkeville.

The tired troops of Longstreet combined I and III Corps trampled through Deatonville around midnight and continued over Little Sayler’s Creek. After a short rest, they resumed the march at daybreak, heading for Rice’s Station. Along the way, Longstreet was informed by locals that a detachment of Yankee infantry and cavalry had recently passed through. This detachment consisted three companies of cavalry and two infantry regiments under Brig. Gen. Theodore Read, sent by Ord to capture the High Bridge at Farmville. Longstreet immediately dispatched Brig. Gen. Thomas Munford’s and Maj. Gen. Thomas Rosser’s divisions to ride hard for the bridge and secure it for the army’s retreat.

Stretched out for miles behind Longstreet’s combined corps were troops in Anderson’s command, Ewell’s reserve corps, the main wagon train and artillery reserve, and Gordon’s corps acting as the rear guard. While the Confederates were headed west, the three corps of the Army of the Potomac under Meade were headed north for Amelia Court House. Bluecoats from Humphreys’s II Corps advancing on the left of Meade’s advance soon spotted the Confederate wagon train and Gordon’s rear guard near Amelia Springs. Skirmishers quickly confronted them, followed by an artillery battery.

Sheridan sent his troopers toward Deatonville, and they soon spotted columns of Confederates and wagons. Lee’s army was again moving, and Sheridan urged Grant to attack. Wright’s VI Corps marched to support Sheridan at Deatonville, while II Corps headed to Amelia Springs to follow after the Rebel rear guard. V Corps was ordered to take the right of the Army of the Potomac’s advance.

Read’s raiders, meanwhile, neared High Bridge. While the infantry took up positions at Watson’s Farm, Read sent his cavalry under Colonel Francis Washburn to scout the bridge. They found it defended by the 3rd Virginia Reserves, hunkered down behind an earthen redoubt. When the Federal troopers spread out to outflank them, the Virginians abandoned their redoubt and hurried back to Farmville.

By that time, Rosser and Munford had arrived and were attacking the Federal infantry. Washburn, in turn, led the cavalry back and attacked the Rebels. In brutal fighting, Washburn took a bullet to the mouth and a saber cut across the skull, knocking him to the ground. Read was killed. With the Union cavalry shot and cut to pieces, the Confederate troopers attacked the two Federal infantry regiments and pushed them back to the Appomattox River, where they surrendered.

Clash at Little Sayler’s Creek

Elsewhere, things were going better for the Federals. Crook’s cavalry harassed Gordon’s corps at Deatonville. Leaving them, the troopers attacked Pickett’s division and Johnson’s division of Anderson’s command at Holt’s Corners. One Federal brigade managed to burn another 20 wagons before being driven off. The troops of Johnson’s and Pickett’s divisions now threw up some breastworks, causing Crook’s men to withdraw, but there was now a two-mile-wide gap between Anderson’s men and Mahone’s division ahead of them.

Custer’s division crossed over Little Sayler’s Creek and immediately saw the dangerous gap in the Confederate line of retreat. The men quickly fell upon some Rebel artillery, forcing their way through the gap and capturing most of the guns. Elements of Pickett’s battered division arrived, and Custer pulled back. He was soon reinforced by the two other cavalry divisions under Maj. Gen. Wesley Merritt, who was temporarily in command while Sheridan was busy elsewhere.

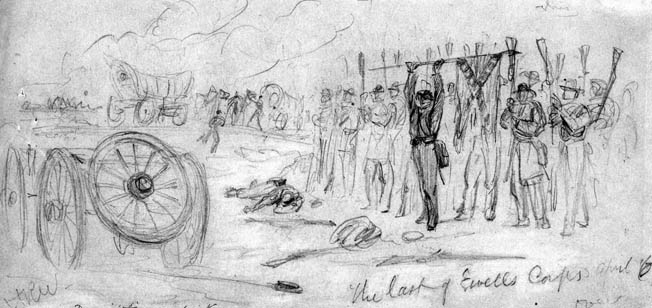

Crossing Little Sayler’s Creek, Anderson’s troops reached Marshall’s Crossroads a mile away, where they found Federal cavalry blocking their route. Ewell, in the rear of Anderson’s corps, was quickly informed of the roadblock ahead and sent the wagon train moving in a northerly direction. Gordon’s corps trailed after them, leaving Ewell without a rear guard.

Ewell pushed over Little Sayler’s Creek and took up position on a ridge west of the waterway. He rode on to meet up with Anderson and decide what they should do about the Federal cavalry blocking their way. The enemy decided that for them when the Union VI Corps appeared behind Ewell. “In full view on the valley’s eastern brink,” wrote a Georgian in Ewell’s command, “the corps was massing into the fields at a double quick, the battle lines blooming with colors, growing longer and deeper at every moment, the batteries at a gallop coming into action. We knew what it all meant.”

At about 5:15 pm, 20 Federal guns opened up on Ewell’s men. Sheridan, who was now on the scene, placed Maj. Gen. Frank Wheaton’s division on the left and Brig. Gen. Truman Seymour’s division on the right in preparation for an attack. VI Corps’ other division, under Maj. Gen. George Getty, had yet to arrive. Meanwhile, Merritt was preparing to attack Anderson with his three divisions.

Ewell’s men built breastworks but having no guns to reply, they could only crouch down and wait for the shelling to end a half hour after it began. To face the attack, Ewell placed Custis Lee’s troops on the left of his position, while Commodore John Tucker’s battalion of sailors and marines, who had earlier scuttled their vessels and joined the retreating army, moved into place in the right rear. On the far right was Maj. Gen. Joseph Kershaw’s division.

At about 6 pm, the two Federal divisions waded across Little Sayler’s Creek and reformed on the other side. Confederate skirmishers fell back as the bluecoats continued their advance toward the enemy’s breastworks, which soon erupted with flame and smoke. Ewell’s men let loose a deadly volley, followed by a second. Two regiments of Colonel Oliver Edwards’ brigade in Wheaton’s division broke and scrambled back to the creek.

Soldiers from Custis Lee’s division led by Colonel Stapleton Crutchfield chased after them across the creek. Hand-to-hand fighting broke out as the opponents bayoneted each other and swung their rifles as clubs. The remaining regiments of Edwards’ brigade wheeled around and began pouring a deadly fire into the gray-clad troops. Crutchfield went down with a bullet to the head. Federal artillery opened up, the canister adding to the Confederates’ misery and forcing them to fall back to their works.

The Federals attacked again, this time hitting the Rebel flanks. Confederate Major Robert Stiles, who had been part of the counterattack, observed, “By the time we had well settled into our old position we were attacked simultaneously, front and rear, by overwhelming numbers, and quicker than I can tell it the battle degenerated into a butchery and a confused mêlée of brutal personal conflicts.” Almost 3,400 of Ewell’s command surrendered, while another 1,450 managed to escape. Among the captured were Ewell, Custis Lee, Kershaw, and three other Confederate generals.

“Let the Thing Be Pressed”

The situation was no better for Pickett’s and Johnson’s divisions. Crook’s troopers attacked the right held by Johnson, while the rest of the troopers hit the Confederates’ front. Brig. Gen. J. Irvin Gregg’s cavalry brigade, attacking dismounted, shoved back Johnson’s flank, but Custer’s troopers were driven back a couple of times by Pickett’s men. Custer attacked again, this time breaking through the Rebel ranks. Anderson’s corps shattered; some men managed to escape, but about 2,600 surrendered. Robert E. Lee, seeing his demoralized troops flee the field, cried out, “My God! Has the army been dissolved?”

Gordon’s corps, following the wagon train, attempted to make a stand to slow the II Corps pursuit. The Federals kept pushing them hard. The wagons became bottlenecked at two bridges over the forks of Little and Big Sayler’s Creeks, while Gordon positioned his troops on a ridge to the east. Two II Corps divisions again pressed the Confederates back toward the creek, where panicky teamsters began cutting their horses and mules out of their traces and fleeing across the waterway. Darkness ended the fighting, but not before 300 Confederate wagons were lost, along with 70 ambulances and three guns. Another 1,700 soldiers were captured as well.

The Army of Northern Virginia could ill afford the loss of 7,700 men. Anderson, Pickett, and Johnson were soon relieved of their commands. Sheridan, reporting on the victory at Little Sayler’s Creek to Grant, urged, “If the thing is pressed I think that Lee will surrender.” When the message was forwarded to him, President Lincoln responded, “Let the thing be pressed.”

Burning Bridges

On the morning of April 7, Longstreet’s mud-spattered men, after marching all night, finally began stumbling into Farmville, where much needed rations awaited them. There, two railroad bridges spanned the Appomattox (including the High Bridge), along with two wagon bridges in the Farmville vicinity. When the last of Lee’s men crossed over to the north side of the river, Lee ordered the bridges destroyed.

Brigadier General E. Porter Alexander, Longstreet’s artillery chief, thought marching west on the north side of the Appomattox was a bad route. He would later write that the army had been “in a sort of jug shaped peninsula between the James River and Appomattox and there was but one outlet, the neck of the jug at Appomattox Court House, and to that Grant had the shortest road.” Despite Porter’s reservations, the last of troops managed to cross the stream—none too soon, as the Federals were close behind.

The order to burn the High Bridge and the wagon bridges was delayed, and by the time Confederate engineers began to torch them, the 19th Maine Infantry arrived and put out the fire on the wagon bridge. The rest of their brigade, commanded by Colonel William Olmstead, was soon moving across it. Mahone attempted to recapture the wagon bridge but was driven back as more and more Federal regiments crossed over. Mahone’s men were soon in full retreat along with Gordon’s corps.

At the High Bridge, pioneers of the 2nd Division managed to put out that fire as well, saving most of the spans of the towering bridge. Elsewhere, Alexander destroyed the other two bridges north of Farmville before the Federals could use them. Meanwhile, the ration train steamed out of Farmville before it fell into Union hands.

Surrender vs “the Restoration of Peace”

The Confederates pushed on to Cumberland Court House, where Mahone’s troops dug in while the wagon train and artillery reserve continued pushing west for Appomattox Court House. After beating back an attack by Colonel George Scott’s brigade of Maj. Gen. Nelson Miles’s division, Mahone’s troops were reinforced by the bulk of the army, with Gordon and Longstreet forming on the right. Scott’s brigade launched another attack around 4:15 pm, but again the Federals were thrown back.

The Federals suffered another setback when Gregg’s troopers attacked the Rebel wagon train but were hit in turn by Munford and Rosser. The Union cavalrymen broke and Gregg himself was captured. Gregg’s troopers reformed and were reinforced by Davies’s brigade, with Brig. Gen. Charles Smith’s brigade acting in reserve and an artillery battery providing support. The Federals again pushed toward the wagons but were thrown back by a brigade of North Carolinians supported by artillery.

Meanwhile, in Farmville, Grant sent a message to Lee asking him to surrender. Lee received the message at 9 pm and showed it to Longstreet, who after reading it replied, “Not yet.” Lee sent a message back to Grant inquiring about surrender conditions, while another night march was undertaken. Lee still hoped to reach Appomattox Station and obtain supplies before pushing west to Campbell Court House and turning south for Danville.

On the morning of April 8, the Federal II and VI Corps resumed the pursuit. Grant followed, having replied to Lee’s query: “The men and officers surrendered shall be disqualified for taking up arms again against the Government of the United States until properly exchanged.” When Lee received the message, he responded that he did not intend to surrender but was merely interested in “the restoration of peace.” Lee suggested a meeting at 10 am the next day.

“Legs Will Win This Battle, Men”

Meanwhile, the fighting continued. Union troopers were in the saddle early, with Crook’s division riding into Pamplin Station around noon, where they captured three locomotives and some cars that had left Farmville the day before. Merritt’s command and Brig. Gen. Thomas Devin’s divisions, meanwhile, were also riding hard, trying to get ahead of the Confederate army. Word reached Sheridan that trains rolling out Lynchburg were nearing Appomattox Station. Sheridan immediately ordered the three cavalry divisions to intercept the trains. Marching behind the cavalry were Ord’s troops and V Corps. Ord told his soldiers, “Legs will win this battle, men.”

The 2nd New York of Colonel Alexander Pennington’s brigade captured three trains bulging with 300,000 rations and supplies; a fourth train managed to escape. It was yet another blow to Lee’s army. At 10 am the wagon train and reserve artillery, as well as their cavalry escort, reached Appomattox Court House and pushed on for another couple of miles toward Appomattox Station. Around mid-afternoon they stopped to eat, but did not post pickets. Union cavalry soon arrived. Pennington’s brigade attacked first but was driven back with canister. The 3rd Brigade under Colonel Henry Capehart attacked next but was also forced back. Finally, at 9 pm, Custer launched a massed attack with all three of his brigades. This time the Federal troopers overran the position, capturing 1,000 men and grabbing 200 wagons and 30 guns.

Around midnight, Grant received Lee’s second message, which angered Grant’s chief of staff, Brig. Gen. John Rawlins, who thought it “a positive insult.” Grant did not take it that way. The next morning he responded to Lee that he had no authority “to treat on the subject of peace” but again called for Lee to surrender. Grant rode out to join Sheridan.

Back at Appomattox Court House, Lee intended to push through the Federal cavalry in his front. Gordon and Fitzhugh Lee moved to attack Brig. Gen. Charles Smith’s brigade of Crook’s division, which was positioned on a ridge overlooking Appomattox Court House. The Confederate cavalry quickly captured two enemy guns and drove back the pickets, then pushed on toward the ridge where the bulk of Smith’s men were blazing away with their Spencer repeating carbines. The Confederates pressed the attack while more horsemen arrived under the command of Brig. Gen. Ranald Mackenzie and Colonel Samuel Young (now in charge of Gregg’s brigade). Just in time, Ord, Custer, and Devin began to arrive with reinforcements.

With more bluecoats massing, Fitzhugh Lee retreated hastily toward Lynchburg. Gordon’s men, badly outnumbered, continued fighting. When asked by Lee’s assistant adjutant general about the situation, Gordon replied bluntly, “I have fought my corps to a frazzle, and I fear I can do nothing unless I am heavily supported by Longstreet’s corps.” But Longstreet had his hands full, facing the II and VI Corps at New Hope Church, four miles to the east. Alexander’s troops began preparing fieldworks on a nearby ridge to make a last stand.

Lee Finally Surrenders

It was too late for that. Lee, realizing that the only open escape route was to the northwest, an area devoid of any major roads and completely opposite of the direction in which he wanted to go, bowed to the inevitable. As couriers from both armies hurried white flags of truce to the front lines, Lee rode out at around 8:30 am, having first dispatched Colonel Charles Marshall to Grant, asking him to meet with Lee about surrendering. When Grant got the message, a meeting was quickly set up in the Appomattox Court House home of Wilmer McLean. Lee arrived first, resplendent in a full-dress gray uniform, with Marshall and an orderly. At about 1:30 pm, a rumpled and mud-spattered Grant arrived with a vanguard of 12 high-ranking officers.

The ensuing parley lasted about 90 minutes, with the two commanding generals exchanging small talk about their time in Mexico before getting down to serious negotiations. “I met you once before, General Lee, while we were serving in Mexico, when you came over from General Scott’s headquarters to visit Garland’s brigade, to which I then belonged,” said Grant. “I have always remembered your appearance, and I think I should have recognized you anywhere.” “Yes,” said Lee, “I know I met you on that occasion, and I have often thought of it, and tried to recollect how you looked, but I have never been able to recall a single feature.”

If Grant took offense at the probably unintended slight (Lee was exhausted), he did not show it. He continued to chat amiably. “Our conversation grew so friendly,” Grant recalled, “that I almost forgot the object of our meeting.” Finally, Lee interrupted to say, “I suppose, General Grant, that the object of our present meeting is fully understood. I asked to see you to ascertain upon what terms you would receive the surrender of my army.”

The Army of Northern Virginia was to lay down its arms and the men were to be paroled and could return to their homes, Grant responded, adding after some prodding that he would allow the troops who owned horses to keep them for use in their spring planting. “This will have the best possible effect upon the men,” said Lee. “It will be very gratifying and will do much toward conciliating our people.” Grant further offered to provide 25,000 rations for the Confederate soldiers and the remaining Federal prisoners.

The two commanders signed copies of the surrender documents and shook hands. Lee walked onto the porch and called for his horse, Traveller, to be brought around from the rear. Then he somewhat automatically returned the salutes from various Union officers milling about the porch and yard. He mounted Traveller and rode off. Grant, coming onto the porch, silently doffed his hat; Lee returned the gesture. Other Union officers also uncovered their heads as Lee passed by.

“It’s All Over Now!”

Inside the parlor at the McLean House, things were considerably less polite. Phil Sheridan and his fellow officers on the scene engaged in a sudden frenzy of souvenir hunting. Despite the protests of homeowner McLean, Sheridan and the others gleefully looted the furnishings where the historic surrender had taken place. Tables, chairs, candlesticks, inkstands—even chunks of upholstery—were carried off. Sheridan, whose victory a week earlier at Five Forks had done so much to seal the Confederates’ fate, plunked down $20 for the pine table on which Grant had signed the surrender document. The next day he presented the table to Custer as a gift for Custer’s beautiful young wife, Libbie, along with a graceful note praising her “very gallant husband” for his role in bringing about the end of the war.

Word spread rapidly of Lee’s surrender. Maj. Gen. George Gordon Meade, commander of the Army of the Potomac, threw his arms into the air and shouted, “It’s all over boys! Lee’s surrendered! It’s all over now!” Officers and men embraced each other without regard to rank. Many cried. Hats, coats, knapsacks, cartridge boxes, canteens, haversacks, boots—anything the solders could grab—were tossed into the air. Regimental bands broke into spontaneous versions of “The Star-Spangled Banner” and other patriotic airs. Artillerymen began firing salutes. Grant, irritated, ordered everyone to stop celebrating. “The Confederates were now our prisoners,” he wrote in his memoirs, “and we did not want to exult over their downfall.” At 4:30 pm he thought to send a brief message to Secretary of War Edwin Stanton: “General Lee surrendered the Army of Northern Virginia this afternoon on terms proposed by myself.”

Meanwhile, Lee rode back to inform his men of the day’s events. As he entered his lines, groups of soldiers crowded around to meet him. “General, are we surrendered?” one man wanted to know. Many were weeping. Tears formed in Lee’s eyes as well. When he reached his headquarters tent he dismounted, then turned to offer a parting word to the watching group. “I have done the best I could for you,” he said. “My heart is too full to say more. Goodbye.”

The next day, having regained his composure, Lee issued his final order to his troops—General Order Number 9. Generations of Southern schoolchildren would learn to recite it, word for word: “After four years of arduous service, marked by unsurpassed courage and fortitude, the Army of Northern Virginia has been compelled to yield to overwhelming numbers and resources. I need not tell the brave survivors of so many hard fought battles, who have remained steadfast to the last, that I have consented to the result from no distrust of them. But feeling that valor and devotion could accomplish nothing that would compensate for the loss that must have attended the continuance of the contest, I determined to avoid the useless sacrifice of those whose past services have endeared them to their countrymen. By the terms of the agreement officers and men can return to their homes and remain until exchanged. You will take with you the satisfaction that proceeds from the consciousness of duty faithfully performed, and I earnestly pray that a Merciful God will extend to you His blessing and protection. With an increasing admiration of your constancy and devotion to your country, and a grateful remembrance of your kind and generous considerations for myself, I bid you all an affectionate farewell.”

On April 12, the Confederate army marched out between two lines of Federal soldiers on the stage road east of Appomattox to stack their rifles. As the last brigade was handing over its flags and guns, the bluecoats gave three cheers, causing many of the Southerners to break down. As one Confederate officer remembered, “This soldierly generosity was more than we could bear.” There would be plenty of time now for cheering and weeping. The Army of Northern Virginia’s war— and soon the entire Civil War—was over at last.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments