by Pat McTaggart

On the vast Eastern Front, the Demyansk salient represented little more than a smudge on the battle map. For the Russians, however, the salient was a festering boil that would not go away. Members of the Stavka (Soviet high command) referred to it as a dagger pointed at the heart of the Motherland—Moscow. The Germans defending the salient simply called it “der Kessel”—the Cauldron.

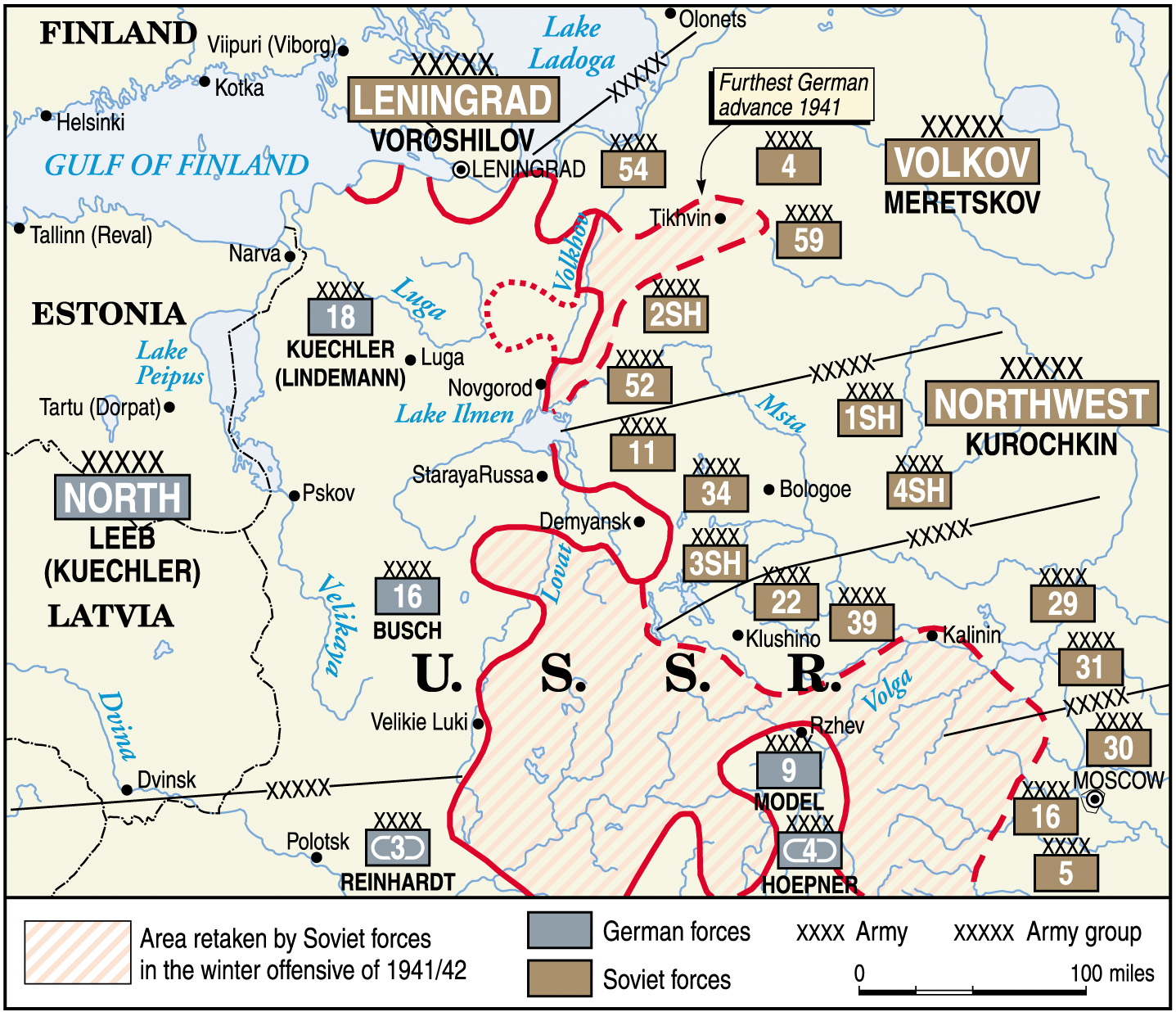

The history of the Demyansk Kessel begins with the 1941-1942 Soviet Winter Offensive. On the northern sector of the front, nine Russian armies attacked Field Marshal Wilhelm Ritter von Leeb’s Heeresgruppe Nord (Army Group North) with the objectives of breaking the siege at Leningrad and pushing the Germans farther west, away from Moscow. Von Leeb’s command consisted of Col. Gen. Georg von Küchler’s 18th Army and Col. Gen. Ernst Busch’s 16th Army. Soviet dictator Josef Stalin also hoped that the two German armies could be encircled and destroyed by lightning thrusts and rapid maneuvers.

Costly Decisions on Both Sides

A combination of rigidity in command and lack of coordination of the Russian forces, coupled with Hitler’s “no retreat” order and stubborn German resistance, foiled the Soviet dictator’s grandiose plan. Both the Germans and the Russians paid dearly for their leaders’ decisions.

One of the most hotly contested areas on the northern sector was the region containing the Valdai Hills and the town of Demyansk. A vital rail link that connected Moscow and Leningrad was located in the town, and both sides fought bitterly for control of the area.

Braving the Elements Along With the Front Lines

General Walter Graf von Brockdorff-Ahlenfeldt commanded the II Army Corps, which was charged with defending the Demyansk sector. The 54-year-old count already had a distinguished military career, which began in 1907. During the 1940 French Campaign, von Brockdorff was awarded the coveted Knight’s Cross while leading the XXVIII and II Army Corps.

When the Soviet offensive began in January 1942, von Brockdorff had three divisions under his command. The 12th Infantry Division, temporarily commanded by Colonel Karl Hernekamp, was raised from Mecklenberg troops. General Wilhelm Bohnstedt’s 32nd Infantry Division consisted of men from Pomerania and Prussia, while General Erwin Rauch’s 123rd Infantry Division came from Brandenburg. The men of these divisions had experienced the heady days of the blitzkrieg advance in Russia. Now, they were facing a vastly superior enemy while freezing in their threadbare summer uniforms.

Holding Demyansk at All Costs

As von Brockdorff’s men fell back under the onslaught of Maj. Gen. P.A. Kurochkin’s Northwest Front, orders came from Berlin that Demyansk must be held at all costs. Control of the area was vital, and as long as the rail link was in German hands, rail supply on a large scale between Moscow and Leningrad would be impossible.

On January 9, Kurochkin’s 3rd and 4th Shock Armies smashed into two regiments of the 123rd. Strongpoints were wiped out, and Red Army troops poured through huge gaps in the German line. By January 12, von Brockdorff had received orders to pull back toward Demyansk. On his left flank, General Christian Hansen’s X Army Corps was also falling back under the fury of the Soviet assault. At the time, Hansen’s command consisted of the Schleswig-Holstein 30th Infantry Division (General Kurt von Tippleskirch), the Schleswig-Holstein and Hanoverian 290th Infantry Division (General Theodor Freiherr von Wrede), and General Theodor Eicke’s SS “Totenkopf” (Death’s Head) Division.

“Your Calculations Are of No Consequence”

Although the Russians pressed the Germans hard, they could not exploit their initial successes in the northern sector. Cut off German units formed strongpoints in villages that were bypassed by Red Army assault troops, and follow-up units had to constantly siphon off forces to try and overcome them. Some of the strongpoints fell, while others held out for weeks.

The situation was fluid and confused, not only for the front-line troops but for the higher commands in the rear area as well. When one German division urgently requested a resupply of ammunition, its corps headquarters radioed back that calculations showed that the division was using too much ordnance. “Your calculations are of no consequence,” came the laconic reply from the division headquarters.

Maintaining Pressure on the German Line

With the attack still in full swing, Kurochkin ordered his 11th and 34th Armies to keep pressure on the German line in front of Demyansk while he sent other units around the enemy flank in a pincer movement. Hitler had demanded that Demyansk be held at all cost, so von Brockdorff and Hansen were denied the freedom of action necessary to prevent the Russian flanking maneuver.

Instead, the German corps and divisional commanders were forced to deploy their troops in an area that was being gradually compressed until it resembled a finger poking out from the main German line of resistance. Throughout January, the German divisions around Demyansk maintained a tenuous contact with the main line. By the end of the month, Stalin had become furious with the German resistance and ordered the completion of the encirclement—no matter what the cost.

Inside the Cauldron

To accomplish the mission, the 1st and 2nd Guards Rifle Corps (Brig. Gens. A.S. Gryaznov and A. I. Lizyukov) were sent to the sector. Since the Germans were ordered to stand fast, it was only a matter of time before the pocket was cut off. On February 9, contact with overland supply lines was severed by the Soviets and the Demyansk Cauldron was born.

Inside the Cauldron were the remnants of several German divisions from the II and X Army Corps and from neighboring Army corps that had been caught up in the Soviet net. Hansen had moved his headquarters to Staraya Russa, some 20 miles northwest of the Cauldron’s western perimeter. Von Brockdorff’s headquarters remained in Demyansk and was given overall command of the encircled German forces. He had approximately 95,000 men to hold the Russians at bay.

From the beginning, supply was a critical problem for the trapped forces at Demyansk. Von Brockdorff estimated that he would need about 200 tons of ammunition, food, and other essentials to allow the men inside the Cauldron to survive. An air supply effort was initiated on February 12, but the trusty “Tante Ju” aircraft (“Aunt Ju”—slang used by German troops for the Junkers Ju-52 transport airplane) only managed to drop less than half that tonnage.

From the beginning, supply was a critical problem for the trapped forces at Demyansk. Von Brockdorff estimated that he would need about 200 tons of ammunition, food, and other essentials to allow the men inside the Cauldron to survive. An air supply effort was initiated on February 12, but the trusty “Tante Ju” aircraft (“Aunt Ju”—slang used by German troops for the Junkers Ju-52 transport airplane) only managed to drop less than half that tonnage.

Meanwhile, as the Soviet inner ring around the Cauldron consolidated, an outer ring was formed on February 15 when Lizyukov’s 2nd Guards Rifle Corps met with units of Maj. Gen. M.A. Purkayev’s 3rd Shock Army. Watching the events unfold, Hitler declared the Cauldron a “Fortress” on February 22. This meant that the German troops in and around Demyansk were expected fight to the last man and last bullet to defend their position.

Besides holding the important rail link, the German forces in the Cauldron served another vital function. Several Soviet armies were now involved in the Demyansk encirclement—forces that could have been used for a drive to the southwest and west. On February 25, General Kurochkin’s Northwest Front was given command of all Soviet forces trying to annihilate the Cauldron. He was told by the Stavka to “squeeze the pocket out of existence in four or five days.”

Reinforcements, including five artillery and three mortar regiments, were sent to help the Soviet general accomplish the mission, but the Germans held fast. By holding out, von Brockdorff and his men were allowing the main German line to stabilize, more than likely saving Army Group North from a catastrophic situation.

Supplying the Cauldron was still a massive problem at the end of February. Almost all of the Ju-52s on the entire Eastern Front had been diverted to help with the airlift, but accidents, bad weather, and Soviet antiaircraft fire still kept the Luftwaffe from delivering the required amount of supplies. Von Brockdorff reported that he was still only receiving about half of what he needed to survive.

“The hunger is terrible,” wrote SS Sergeant Sabisch of the Totenkopf Division. “The aircraft come in the morning and drop their ammunition and supplies … the parachutes open and we watch them fall, and what do we see? Slowly they float towards the forest, to Ivan.”

Another inhibiting factor for the Germans in the Cauldron was the sub-zero temperatures that had plagued the front since December. Siegfried Moldenhauer, an officer in the 12th Infantry Division, could still remember the cold some 50 years later. “I saw brave men—men who would not hesitate to charge an enemy strongpoint with nothing more than a bayonet—weep uncontrollably because of the freezing weather,” he wrote in a 1993 letter to the author. “We had little more than our summer uniforms and our jackboots as protection in temperatures that reached minus 20 or minus 30 degrees. We dug holes in the snow to protect ourselves, because the ground was like iron. Imagine living like this for weeks on end and still trying to find the strength to fight off the enemy.”

By March, the Soviet offensive had fizzled out and Hitler became determined to launch an operation to free the besieged Germans at Demyansk. Code-named “Brückenschlag” (Bridging), the plan called for a five-division attack to strike the Russian outer ring. Meanwhile, German forces inside the Cauldron would attack westward to link up with the relief force. Command of the strike force outside Demyansk was given to General Walter von Seydlitz-Kurzbach.

The five German divisions, 5th Light, 8th Light, 18th Motorized, and the 122nd and 329th Infantry Divisions, supported by the I/203rd Panzer Regiment and the 659th and 666th Sturmgeschütze (assault gun) battalions, were assembled for the attack. While von Seydlitz marshaled his forces, the battle inside the Cauldron took an ominous turn. The Soviet 1st and 4th Airborne brigades managed to infiltrate the German defenses, and von Brockdorff was forced to deplete his already undermanned lines to fight the infiltrators in order to keep his interior supply lines open. Fighting between the paratroopers and the Germans did not end until the last of the Soviets were destroyed on April 7.

Brückenschlag began on March 21 with an artillery barrage and a strong air strike. The Soviets responded in kind, and the air was filled with high explosives and dueling aircraft. Luftwaffe pilots finally gained the upper hand, shooting down several Russian planes. Among the Soviet airmen lost was Lieutenant Frunze, whose father had commanded the Bolshevist Army during the Russian Civil War.

With the Russians driven from the sky and most of the Red Army artillery temporarily silenced, von Seydlitz ordered his divisions to advance. Several penetrations were made in the Soviet line, and by March 25, a unit commanded by Captain Max Sachsenheimer of the 5th Light Division had severed a major enemy supply route between Staraya Russa and Ramushevo. The Soviets resisted fiercely, and the colonel commanding the 329th Infantry Division was killed shortly before his men stormed Podepache and freed a trapped battle group from the Totenkopf Division that had fought off the Russians for almost eight weeks.

Caught off guard, Kurochkin hastily shuffled his forces and ordered a counterattack. He began his Order of the Day with the words “Not one more step backward.” The 5th Light Division was hit by several Red Army rifle regiments and tank battalions but managed to hold until General Sigfried Macholz’s 122nd Infantry Division arrived to help stem the Soviet drive.

Russian weather now stepped in as the Rasputitsa (muddy season) began. Temperatures began to rise, and the few roads in the area were suddenly turned into almost impassible quagmires. Soviet and German troops fought each other in knee-deep water and mud as the battle continued, but von Seydlitz’s men continued to push the Russians back. Ramushevo, the vital communications center between Staraya Russa and Demyansk, was taken at heavy cost by a battalion of the 18th Motorized Division. The battalion commander, Captain Dietrich Steinhart, fell with many of his men as they stormed the town. Steinhart was a popular commander and was one of the few junior officers to be awarded the Knight’s Cross during the Polish Campaign.

Now it was time for the second phase of Brückenschlag to begin. Operation “Fallreep” (Gangway), an attack by forces inside the Cauldron, began on April 14. The Totenkopf Division and some elements of the 12th, 30th, 32nd, and 290th Infantry divisions struck out from the western edge of the Cauldron and, after six days of heavy fighting, reached the eastern bank of the Lovat River. On April 21, some SS engineers crossed the swollen river in rafts and made contact with the 5th Light Division. The salient was expanded on both sides of the river, and on May 1 a land supply route to Demyansk was opened.

The first battle for the Demyansk Cauldron had many consequences, and there were more to come. Soviet forces that could have been used to continue the westward drive of the Winter Offensive were instead diverted to try to eliminate the surrounded Germans. The air supply effort gave Reichsmarshal Hermann Göring confidence that the Luftwaffe could supply any encircled force, no matter how large it was. Finally, Hitler was convinced that declaring Demyansk a fortress was the answer to negating the growing Soviet manpower superiority. The next time he issued such a fortress order was at Stalingrad.

Although the supply line to Demyansk was open, the salient was still the focus of attention for both the Russians and the Germans. Stalin saw it as a possible jumping off point for a future offensive toward Moscow, while Hitler looked upon it as a justification for his “stand fast” order and refused to abandon the area as a matter of honor. There was also the vital rail link, which was a central prize for both sides. Therefore, throughout the rest of 1942, the II Army Corps waged its own personal war with the Russians while the tide of battle ebbed and flowed on other fronts. For the defenders inside the salient, Demyansk was still “der Kessel.”

The battle for Demyansk was now four months old, and its cost had already been horrendous. At the end of April, von Brockdorff sent a report to the 16th Army headquarters stating that since January 1, the II Army Corps had received 1,115 Soviet attacks and had repulsed 776 Red Army advances while conducting 376 counterattacks. Enemy fatalities were numbered in the thousands and 3,064 Soviet prisoners were taken. A total of 74 tanks, 52 artillery pieces, and 81 antitank guns were either captured or destroyed. Von Brockdorff put his own losses at 5,101 killed, 15,323 wounded, 2,000 missing, and 5,866 cases of severe frostbite.

As the weather cleared and the Rasputitsa finally came to an end, Stalin planned his spring campaign. By the end of April, the Northwest Front had received five rifle divisions and eight rifle and two tank brigades as reinforcements. Kurochkin planned a two- pronged attack with the 11th Army striking from the northeast and the 1st Shock Army driving up from the southwest. When the Cauldron was once again isolated, he would order the other Soviet armies surrounding the salient to eliminate it.

Kurochkin’s attack began on May 3. The primary objective was to cut the six-mile-wide corridor at the western end of the Cauldron. For more than a month, the Soviets tried to breach the German lines, but von Brockdorff’s men held. When the offensive was finally called off in late June, most of the German divisions were sorely depleted. Totenkopf was at about one-third of its normal strength, and some other divisions were in even worse shape.

The Germans were able to beat back the numerically superior Soviet forces because Kurochkin had become so predictable. His divisions would strike the same point again and again, allowing von Brockdorff to funnel reinforcements to that sector and making it easy for German artillery to preplot firing solutions that rained tons of explosives on the advancing Russians.

For the next few weeks, the situation at Demyansk remained static. By now, the Cauldron resembled a mushroom lying on its side. The western “stem” was about six miles wide, while the wider “cap” of the salient extended some 60 miles to the east. The men of the II Army Corps were holding parts of two Russian fronts at bay, but von Brockdorff’s divisions could also have been of great service on other sectors of the front. Col. Gen. Franz Halder, chief of the Army General Staff, proposed that the Cauldron be evacuated to provide a reserve for Army Group North, but Hitler firmly rejected the idea.

In mid-July, the Russians renewed their attack on the stem of the Cauldron. Halder, in his war diary, recorded on July 17 that “against the corridor to II Army Corps, full stage attack from north and south, prepared by heavy artillery bombardment and supported by tanks and air force. Not withstanding some local enemy gains, the attack was repulsed.”

During August and September, both sides fought to improve their situation. Kurochkin continued to gnaw away at the western edge of the Cauldron while the Germans began planning an operation to widen the narrow supply corridor leading into the salient. Halder still pushed for the complete evacuation of the Cauldron, but Hitler steadfastly refused.

On September 27, the German offensive began with an attack by the 5th Jäger (formerly 5th Light) Division and the 126th Infantry Division on the eastern side of the stem. The two German divisions encircled the 1st Guards Rifle Division by October 2 and stopped at the Lovat River. Phase II of of the offensive saw the Luftwaffe Infantry Division “Meindl” and the Totenkopf, now down to about 350 effective troops, attack from just outside the western edge of the stem. By October 10, the supply corridor had expanded to a width of 10 miles.

The onset of the fall Rasputitsa brought a halt to most operations around Demyansk by mid-October. In both Moscow and Berlin, eyes turned farther east to the life and death struggle at Stalingrad. While Hitler was determined to take Stalin’s city, the Soviet dictator was just as determined to hold it. As Russian units in the city were bled white, the STAVKA was preparing a massive blow that would eventually cut off Col. Gen. Friedrich Paulus’s 6th Army and destroy it. At the same time, another plan was being formulated to annihilate the Demyansk pocket.

Stalin demanded victory, not only against the Germans on the Stalingrad Front, but against Demyansk as well. His Stalingrad offensive was set to begin on November 19. The attack on Demyansk would start on November 28.

To command the Demyansk operation, Stalin chose one of his few close friends—Marshal of the Soviet Union Semën K. Timoshenko. Born in 1895, Timoshenko had commanded a cavalry unit during the Russian Civil War. His friendship with Stalin helped him escape the purges of the 1930s that had decimated the Soviet officer corps. He successfully brought Finland to her knees in 1940 and was temporary commander-in-chief of the Red Army in 1941. As commander of the Western Theater, Timoshenko slowed the German advance on Moscow. His star waned after the disastrous attempt to recapture Kharkov in May 1942, but Stalin still had enough confidence in him to give him this important assignment.

Timoshenko was given a lavish number of men and amount of material to accomplish his mission. The 11th and 27th Armies had a total of 13 rifle divisions, nine rifle brigades, and about 400 tanks. In the south, the 1st Shock Army would hit General Harry Hoppe’s 126th Infantry Division with seven rifle divisions, four rifle brigades, and 150 tanks. While the Soviet strike force snipped off the stem, the 34th and 53rd Armies would attack the northeast and southwest fronts of the salient and pin down the German units defending those sectors.

It seemed like a perfect plan. Timoshenko would have complete air superiority as almost all of the Luftwaffe units in the area had been transferred to other sectors of the Front. The 16th Army had also lost almost all its armor. Its last major armored unit, the 8th Panzer Division, had been shipped off to Vitebsk, leaving the army with a few assault gun companies and some panzer companies from the 203rd Panzer Regiment as a reserve to deal with any armored threat. The armored reserve, known as Group Saur, was under the command of Lt. Col. Freiherr von Massenbach.

All eyes were on Stalingrad as the day of the Demyansk attack approached. As Soviet armies smashed through Hungarian, Romanian, and Italian divisions that were protecting the flanks of the 6th Army, Timoshenko kept receiving new units for his own offensive. The reinforcements moved at night with the snow muffling most sounds that might prematurely alert the Germans.

Inside the Cauldron, von Brockdorff had fallen ill and was replaced by General Paul Laux. The 53-year-old Laux was born in Weimar and had served in the German Army since 1907. His command now consisted of the 12th (Colonel Gerhard Müller), 30th (General Thomas-Emil von Wickende), 32nd (General Wilhelm Wegener, and 122nd (Colonel, soon to be General, Kurt Chill) Infantry Divisions. Also included were two-thirds of the 129th Infantry Division (General Albert Praun) and Infantry Regiment 368 of the 281st Sicherheit (Security) Division under General Wilhelm-Hunold von Stockhausen.

The stem of the Cauldron was defended by Group Höhne (General Gustav Höhne) with the 126th (Hoppe), 290th (General Conrad-Oskar Heinrichs), 123rd (General Erwin Rauch), and 81st (General Erich Schopper) Infantry Divisions and General Gerhard Graf von Schwerin’s 8th Jäger Division. Group Höhne would receive the brunt of Timoshenko’s attack, which would follow the same pattern as earlier Soviet offensives against the salient.

In the early hours of November 28, a massive Soviet artillery barrage hit the German line. When it stopped, the hum of aircraft fill the sky as the Red Air Force bombers and low- level attack fighters appeared from the east. German grenadiers cautiously peered over the lips of their foxholes just in time to see waves of enemy bombers unleash their deadly cargo. The ground shook violently as bombs ripped through the German positions. As the bombers departed, low-level aircraft skimmed over the German lines, strafing anything that moved.

A new sound was heard as the Soviet planes departed. Experienced grenadiers recognized that the low growl of engines and the slight trembling of the ground could only mean one thing. “Enemy tanks approaching!” came the cry up and down the line. Designated tank killer teams hastily prepared to meet the steel monsters bearing down on the German positions. Bundles of grenades had already been taped together and sticky mines were placed close by for instant use as the teams waited for the right moment to begin their deadly game of cat and mouse.

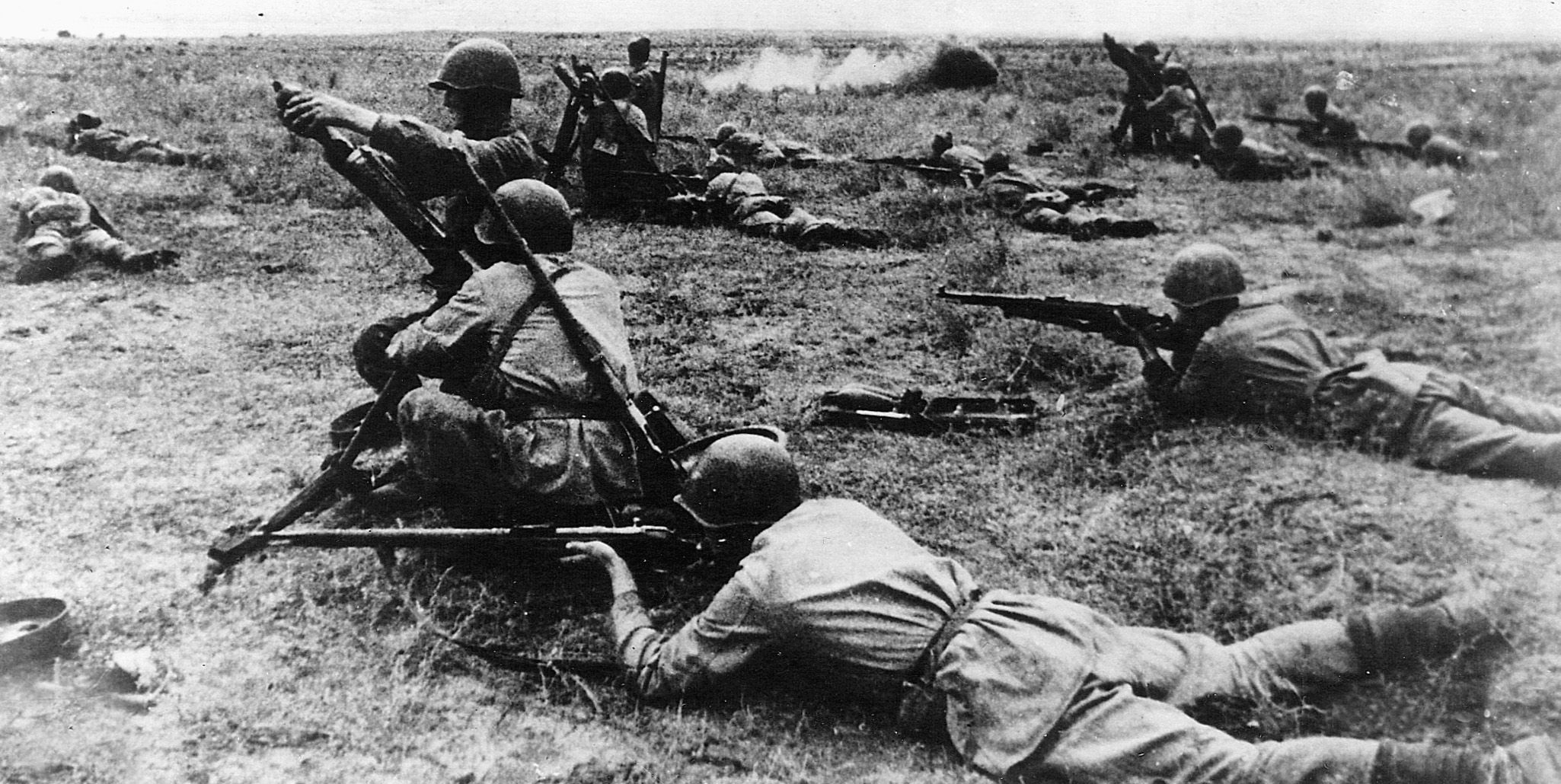

The Soviet storm hit three divisions (290th, 81st, and the 8th Jäger) in the north with the 11th and 27th Armies. In the first wave, two Guards rifle divisions, five rifle divisions, four rifle, and two tank brigades slammed into the German defenses. Russian T-34 tanks led the way, with masses of Red Army infantry following, shouting their blood-curdling war cry, “Urra,” as they charged. Grenadiers in the first line of defenses, crouched low, letting the tanks run over their foxholes. When the tanks continued on their way, the defenders got up and met the Soviet infantry with withering rifle and machine-gun fire.

Now the tank killer teams went into action. In groups of two or three, the Germans stalked their prey, waiting for the exact moment to stick their bundles of grenades into the Soviet tanks’ tracks or to slap a “sticky mine” on an engine housing or turret ring. Without infantry support, several T-34s burst into flames as the teams continued their hunt. It was a deadly contest, where one slip or wrong move could result in being crushed by the steel monsters as they continued their mission of trying to sever the German supply corridor.

Some penetrations were made in the north, and Timoshenko immediately pushed his reserves into the breaches. The tenacity of the soldiers of the 8th Jäger Division was evident as a large force of about 3,000 Soviets was fought to a standstill and then repulsed by a counterattack from 417 men of the division’s Jäger Regiment 28.

A particularly heavy infantry-tank assault struck Schopper’s 81st Infantry Division. His situation was worsened by the fact that his divisional anti tank battalion was not only understrength but was equipped with a hodgepodge of enemy weapons. Nevertheless, the crews stood behind their mixture of 10 French and six Russian heavy anti tank guns and five light German and Czech guns.

As the Russians advanced, the crews fired shell after shell, disabling some of the T-34s while the others kept coming. The light guns were virtually useless, and the crews, firing at point-blank range, watched helplessly as their shells bounced off the sloped armor of the Russian tanks. They died at their positions, bright red blotches of blood blemishing the white snow as the T-34s crushed them. After two days of fighting, the battalion strength was down to eight officers and 208 men, but the sacrifice of the dead had halted the Russians.

Höhne, who had no reserves of his own, ordered drivers, clerks, and cooks into the fray to try and stop the Russian advance. Some companies from Group Saur were also rushed to the scene. Together, the tanks and the rear-area troops managed to prevent a total disaster.

In the south, three Guards rifle divisions, a rifle division, two rifle brigades, one tank and one ski brigade slammed into Hoppe’s 126th Infantry Division. The battle there followed the same path as the fight in the north. Soviet soldiers courageously charged the German positions but were mowed down by the hundreds. About 150 tanks formed the vanguard of the attack, and several went up in flames, victims of the tank killer squads, minutes after passing over the well-constructed German forward positions.

The Russians, blunted in one sector, looked for easier paths through Hoppe’s defenses. A concentrated assault finally resulted in a breakthrough, and Red Army tanks and infantry surged through the breach. The headquarters of Infantry Regiment 422, located behind the lines in Koslovo, suddenly found itself under attack. As Soviet tank cannon fired at point-blank range, officers donned their steel helmets and rushed to join headquarters, personnel already engaging the Russians. A bloody struggle ensued, and only after several of the tanks were destroyed did the remaining Soviet force retreat toward its own lines.

General Laux was under no illusions. His supply line had almost been cut by the heavy attack on the corridor, and the Soviet 53rd and 34th Armies were also making heavy spoiling attacks against the units manning defenses on the eastern edge of the Cauldron. He radioed a request for reinforcements that went directly to Col. Gen. Ernst Busch, commander of the 16th Army. Busch personally answered the plea for help. “Laux,” he said, “I can’t spare a single battalion from the Army front.”

It was the same at Army Group North. The battle for Stalingrad had siphoned off any reserves that might have been sent to help the embattled II Army Corps. Nevertheless, Field Marshal Georg von Küchler, the army group commander, took the risk of withdrawing three divisions from his thinly held front and sent them to the Cauldron with all the speed that they could muster.

When the order came, General Walther-Ernst Risse’s 225th, General Karl von Graffen’s 58th, and General Friedrich Kochling’s 254th Infantry Divisions moved out of their positions around Lake Ladogda and headed south. They arrived a battalion at a time and were hastily sent into sectors that had already been thinned by the Russian onslaught. The three divisions had been instrumental in maintaining the blockade around Leningrad. When the Soviets attacked the Ladogda sector some weeks later, the lack of depth in the area would prove fatal to the plan of starving Leningrad into submission.

Inside the Cauldron itself, the fighting continued unabated. Moscow was demanding results, and Timoshenko was trying to please. He ordered more attacks to try and breach the tenuous line that held the supply corridor, and the battle became even more confused as several penetrations were made in the German lines.

Some 40 years after the battle, Master Sergeant Ernst Wawrock of the 8th Jäger Division recalled the fighting in a letter to the author. “It was utter chaos during those first days of January. I was a platoon leader in the 13th Company of Jäger Regiment 28. The Ivans were very good, and they had forced our company out of three bunkers that were vital to the defense of the area. We were ordered to take them back.

“The enemy fire was very heavy as we moved forward and, one by one, our officers fell—either killed or wounded. The company was being cut to pieces and we clung to any cover that we could find. One of the younger lads had tears in his eyes—I don’t know whether out of fear or frustration.

“I gathered the remaining men around me and told them that the capture of those bunkers was vital, and that there was no one left to do it but us. Positioning most of the surviving men to give covering fire, I set out toward the bunkers with three volunteers. We charged the first bunker and, after a short and bitter fight, we were able to clear it. This was not without cost. All three of my comrades were too badly wounded to continue, so they tried to suppress the enemy fire as I advanced on the other two bunkers.”

Wawrock ran like a man possessed, dodging enemy bullets and reaching the second bunker. He fired madly into the bunker’s slits and tossed a grenade through an opening. Before the smoke had cleared, he was on to the third bunker, where he repeated his actions.

“The surviving members of my company then rushed forward to re-occupy our old positions,” he wrote. “I could not have done this without the bravery and sacrifices of my dead and wounded comrades. The Knight’s Cross that I received for these actions is really a testament to them.”

After a month and a half of fighting, both sides were utterly exhausted. Timoshenko had lost about 10,000 men and 425 tanks, while the Germans claimed to have sustained 17,767 total casualties, many of them killed or missing. Having taken so many losses with so little to show for it, Timoshenko finally called his offensive to a halt in order to regroup and resupply his forces.

By now, the three German divisions from the north had arrived in force, allowing Laux to pull some of his units out of the line for a well-deserved rest. Meanwhile, German positions at the stem and inside the Cauldron were strengthened by engineers in anticipation of a renewed Soviet offensive. Russian “Hiwis” (ex Red Army soldiers working for the German Army) searched for the dead and dug graves in the snow to bury fallen German and Soviet soldiers only a few yards behind the front.

Both sides suffered from the harsh winter during that first month of 1943. Patrols were constant as the Germans and Russians vied for information about the other side, and frostbite became the universal enemy. Some probing attacks took place—sharp, vicious firefights that continued to drain the mental and physical energy of the front-line troops.

“We were fighting three enemies,” Wawrock recalled. “There was Ivan, the horrendous winter and exhaustion. The sunken eyes in the sallow faces of my men were difficult to look at. I’m sure that the average Ivan felt the same.”

While the Germans were strengthening their lines, Timoshenko used his time to assimilate arriving replacements into his battle-weary units. New tanks were also on the way, and plans were already in the works to restart his offensive as soon as possible. Propaganda units were also brought to the front, boasting about the impending annihilation of the 6th Army at Stalingrad while offering the Germans inside the Cauldron safety and warmth if they would only surrender.

In Berlin, Hitler was receiving daily, sometimes hourly, briefings concerning the Stalingrad debacle. General Kurt Zeitzler, who had replaced Halder, also continued to press the Führer on the Demyansk question. Citing the growing enemy superiority around the salient, Zeitzler urged Hitler to withdraw from the Cauldron before it was too late. His pleas fell on deaf ears as Hitler repeated his order to stand fast and not surrender one meter of ground to the enemy.

Things were not as cut and dried inside the Cauldron. “We are in an impossible situation,” Lauz told his staff. “We must take things into our own hands.”

As some engineer units continued to strengthen the Cauldron’s outer perimeter during the January lull in the battle, others went to work cutting down trees in the heavily forested area around Demyansk. Once cut into logs, the wood was lashed together in several layers, which were laid side by side. The bundles were then topped with cinders and sand which were then smoothed over. Several of these “corduroy roads” were hastily constructed, but they would make the movement of men and equipment easier.

Laux also ordered that his wounded be moved to field hospitals closer to the stem of the Cauldron and had all but the most essential equipment collected at points along the improvised road system so that it could head west at a moment’s notice. His major concern was that Timoshenko would renew his assault before everything was ready. His major hope was that Hitler would come to his senses and order a withdrawal from the salient before he took it upon himself to do so.

Zeitzler continued to press the issue. As the disaster at Stalingrad reached its conclusion, Hitler gave in on February 1. The order immediately went out to Laux. “All non-essential equipment is to be withdrawn west of Staraya Russa and the combat area is to be abandoned in 70 days.”

“Finally someone has made him see reality,” Laux said to his chief-of-staff. “Make the necessary preparations at once. Get the wounded out first, then equipment and non-essential personnel. If we are to pull this off, we can’t be hindered in any way. Once the Russians figure out what we are doing, they will come at us with everything that they have.”

The Germans used every trick they knew to keep the Soviets in the dark. Dummy positions were built along the perimeter and deceptive radio messages were transmitted indicating that reinforcements were on the way to help defend the Cauldron. Rumors that new divisions and tanks would be arriving soon were spread among the local population with the full knowledge that they would eventually reach Red Army intelligence officers, and patrols became more aggressive, keeping the Russians from coming too close to the perimeter.

While these operations were in progress, plans were being worked out for the phased withdrawal of combat units from the salient. The units farthest to the east would pull back to positions manned by divisions in the center of the pocket. All of these units would then withdraw to the next defensive line. With luck, Laux hoped that the Cauldron could be evacuated in a few weeks instead of the 70 days called for by Berlin.

Meanwhile, Timoshenko was somewhat baffled by the conflicting reports he was receiving. Although German radio traffic and information from local spies told him that the enemy was reinforcing the Demyansk salient, a few intercepts spoke of the withdrawal of troops and equipment. The few Soviet patrols that made it to the German lines brought back reports of undermanned positions and engine noises indicating the westward movement of vehicles. Stalingrad had shown Hitler’s stubbornness against all logic, but perhaps the defeat had convinced the Germans that maintaining a hopeless position was nothing more than suicidal. While the marshal vacillated, Laux’s preliminary evacuation continued.

Finally, Timoshenko decided to act. On February 15, he ordered 12 rifle divisions supported by three tank and three rifle brigades to attack the land bridge at the base of the Cauldron. Once again, it was the units of Group Höhne that felt the brunt of the assault. The artillery barrage caught the Germans off guard, but the Soviet infantry that followed still faced a wall of deadly fire during the advance. In the north, the 290th, 58th, and 254th Infantry divisions beat back several tank-led attacks. Soviet soldiers literally climbed over their own dead as they steadfastly tried to take the German positions.

The first Shock Army in the south made better progress. Harry Hoppe’s 126th Infantry Division faced the full fury of six rifle divisions and three rifle brigades, which were supported by 50 tanks. The grenadiers put up fierce resistance, but the depleted battalions could not stem the Red tide.

Infantry and T-34s stormed forward on a three-mile-wide front. German strongpoints were bypassed, and the main striking force advanced two miles into Hoppe’s position. The town of Beressovo fell in a bitter fight only after the German defenders had destroyed 25 enemy tanks. Timoshenko then ordered his spearhead to turn northwest and capture the important road junction at Godilovo.

Another fierce battle developed in that area as Russian tanks and infantry, encouraged by their capture of Beressovo, surged ahead, regardless of losses. The 126th was stretched to its breaking point, but Hoppe’s men continued to hold the approaches to the town. Reinforcements arrived in the nick of time in the form of a regiment from the 5th Jäger Division.

Faced with a determined defense in their front and a flanking attack from the Jägers, the Soviets were forced to pull back. Slowly, the Germans pressed forward, clearing out pockets of Russian resistance and retaking most of their lost positions by the end of the day.

The fighting had once again been costly for both sides, but the Russians were still receiving a steady flow of replacements while the Germans were not. Laux and Höhne were taxed to the limit with trying to fill the gaps in their ranks, and both generals knew that another large-scale offensive against the Kessel could only result in disaster. In a radio message to Busch, the German commanders requested that whole-scale evacuation begin immediately. Busch relayed the message to Berlin, where it was agreed that February 17 would be the date for the withdrawal. On that date, the codeword “Ziethen” was flashed to all senior headquarters inside the Kessel. It was time to put Laux’s plan into operation.

In the most eastern sector of the Kessel, companies of the 32nd 329th Infantry divisions began moving west by late afternoon. Rear-guard forces were left behind to deceive the 37th Army patrols that roamed the no-man’s land along the perimeter. The sporadic machine-gun and rifle fire from the German defenses had its effect, and the two divisions marched throughout the night until they finally reached the lines of the 12th and 30th Infantry divisions before continuing their trek to the west.

On February 18, the 12th, 30th, and 122nd Infantry divisons began their own withdrawal, helped by a snowstorm that obscured visibility and muffled the sounds of the retreating troops. By that afternoon, Soviet patrols had entered the eastern part of the Cauldron, only to find the enemy positions abandoned. Messengers fought their way through the blowing snow to report their find to their commanders, but it was not until the 19th that Timoshenko realized that he had been tricked.

The Soviet marshal sent angry messages to the commanders of the 53rd and 34th armies ordering them to advance immediately. Ski and cavalry units led the pursuit, fighting running battles with the troops charged with guarding the withdrawal. Following somewhat more slowly were armored and infantry units that had tough going in the newly fallen snow from the previous day. The “corduroy roads” that the Germans had built would be of no use to the advancing Soviets, as they were broken up after the last German troops had passed.

Inside Demyansk, the long gray columns of withdrawing Germans trudged through the narrow streets of the town. Orders had been given to maintain strict silence, and no open fires were to be lit. The temptation was too great for some, however, and soon groups of soldiers were standing around burning fires that had been lit in empty barrels, concerned only with warming themselves for a few minutes before continuing their march westward. Inevitably, the fierce wind carried sparks from these fires to the thatched roofs in the town.

Before long, fires were raging in every section of Demyansk. Withdrawing troops were ordered to bypass the town while soldiers and civilians waged a futile effort to stop the conflagration. The only building the Germans were able to save was a hospital that had 50 Red Army soldiers as patients. As the town was being evacuated, a few medical personnel volunteered to stay behind with the wounded until the Soviets arrived.

At the corridor of the Cauldron, Timoshenko brought the 1st Shock and 27th armies into play again. Bolstered by arriving units of the 32nd and 329th Infantry divisions, Group Höhne held off several savage attacks and kept the path open for other units streaming west. German artillery pummeled the attacking Russians, using shells that had been saved for just such an occasion, and the Soviets began to falter then fall back in the face of the barrage.

By February 22, the 12th, 30th, and 122nd Infantry Divisions had withdrawn to the fifth defensive position on the western end of the salient. There they halted several attacks from the pursuing 53rd and 34th armies, while engineers waited to demolish key bridges when the last stragglers were across.

The Soviets tried desperately to capture these bridges intact. In February, Russian ski units surrounded a group of engineers that was trying to make it back to the German lines after destroying a bridge in the face of the advancing Soviets.

First Lieutenant Günther Vollmer of the 122nd Infantry Division was tasked with rescuing the trapped men. In a letter to the author, Vollmer described the action. “I was leader of the 3rd Company of Grenadier Regiment 411. We were badly understrength after earlier battles in the Cauldron and the men were exhausted, but our trapped comrades had bought the II Army Corps precious time and no one complained when we set out late in the afternoon.

“It was hard going through the deep snow, which only added to our fatigue. Darkness came early, which both helped and hindered us. In the distance, we heard gunfire and the occasional grenade. That meant that we were getting closer. I divided the men into groups as we continued—some to give us support fire and others to attack.

“Ivan was not expecting an assault on his rear, and with the element of surprise we broke through the ring of Soviets that had encircled our comrades. As my men provided cover for the flanks, the engineers rushed through our corridor.”

Vollmer now turned the tables on the Russians. The addition of the freed engineers gave him a potent force, and instead of heading back to the German lines Vollmer decided to carry on his attack. While his rear guard fought a stubborn delaying action, the remaining troops formed a semicircle that gradually forced the flanks of the Soviets inward.

The hunters were now the prey as Vollmer’s men tightened the noose around the Russians, and the Red Army troops were finally forced to surrender. Vollmer returned not only with the freed engineers, but with several Soviet prisoners as well. He was later awarded the Knight’s Cross for his initiative and valor. “That award was a reflection on the entire Company,” he later wrote.

The next two days saw more heavy fighting as the Soviets tried to thwart the German withdrawal. Timoshenko threw everything he had at the enemy, but to no avail. He could only watch helplessly as the remainder of the II Army Corps slipped through his grasp.

The evacuation of the Cauldron was completed on February 27. Laux’s II Army Corps and Group Höhne had pulled it off—not in 70 days, but in 10! An important aspect of the evacuation was the saving of most of the divisions’ heavy equipment. This meant that the divisions of the II Army’s corps could be refitted just behind the lines instead of having to travel to depots in Germany for new equipment and training. The Demyansk divisions, remaining so close to the front, could also provide an important reserve pool when the Soviets opened their spring and summer offensives against Army Group North.

By 1943, the opening of a German offensive toward Moscow was nothing more than a pipe dream, but Hitler stubbornly refused to let go of the Demyansk salient until it was almost too late. The evacuation of the Cauldron was one of his last rational decisions of the war, and it saved about 100,000 German troops that could fight another day. Unfortunately for the Germans, the defensive tactical victory at Demyansk was never fully appreciated by Hitler. Trading ground for a great number of enemy casualties was the only way to grind down the Soviet war machine.

Fortunately, for the rest of the world, Hitler’s constant fixation on holding every inch of conquered land proved to be the downfall not only for himself, but for the Third Reich as well.

Pat McTaggart of Elkader, Iowa, is an expert on World War II and the Eastern Front.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments