By Timothy Koenig

“For sugar the government often got sand; for coffee, rye; for leather, something no better than brown paper; for sound horses and mules, spavined beasts and dying donkeys; and for serviceable muskets and pistols, the experimental failures of sanguine inventors, or the refuse of shops and foreign armories.” So wrote Harper’s Monthly journalist Robert Tomes in July 1864. What Tomes was describing was far from uncommon during the American Civil War, a war that many have put on high moral ground beneath the umbrella of righteousness. But in that war, as with most wars throughout history, thievery and corruption ran rampant. This corruption, involving not only suppliers and manufacturers in the North but also high government officials, resulted in the unnecessary loss of life for many Union soldiers and was so costly as to prolong the war many months after it might have come to an end.

Corruption in all forms was familiar to Americans long before the Civil War. The struggle with corruption can be seen in one of the earliest debates surrounding Alexander Hamilton’s economic policies, particularly his views on the need for increased manufacturing. Many common people feared that new economic policies would be the basis for systematic corruption. Southerners, especially, were wary of an industrialized manufacturing society and centralized government itself.

Andrew Jackson, who had been cheated out of the White House in 1824 by political chicanery between his main rivals, John Quincy Adams and Henry Clay, built much of his political platform on the struggle against corruption. He greatly feared systemic corruption, which he viewed as inevitable if the national bank was rechartered, owing to the large amount of power a small percentage of financiers would hold over the government. Ironically, Jackson himself was accused of corruption by Clay, the key partner in the “Corrupt Bargain of 1824” that swung the presidency to Adams, despite the fact that Jackson had received a clear majority of popular votes. Clay, who was more or less immune to shame, said of Jackson’s free exercise of executive powers: “The question is no longer what laws will Congress pass, but what will the Executive veto?”

Although the idea of popular sovereignty was favored by many Americans, the susceptibility of the people to be controlled by a demagogue made Clay and other politicians uneasy. By the mid-1850s, corruption had spread even into the lowest political levels. “Congress is a humbug and Washington is no place for an honest man,” Benjamin French wrote in 1853 of his fellow United States representatives. Bribery and self-interest were commonplace in Washington, and French was one of the few officials who cared about the issues that were forming the nation rather than the personal rewards of his actions.

Corruption and Government Contracts

Corruption would have a large and deleterious impact on the Union war effort. At the beginning of the war, thousands of new soldiers had to be supplied, leaders had to be appointed, and some form of military organization had to be established. In many wars, an economic boom can follow the sudden need for material and labor. The Civil War was no exception. The railroad system was already on the rise due to its advantages over existing canals, but the Civil War would take railroad usage to another level. A more humble industry that prospered during the war was the lamp oil industry.

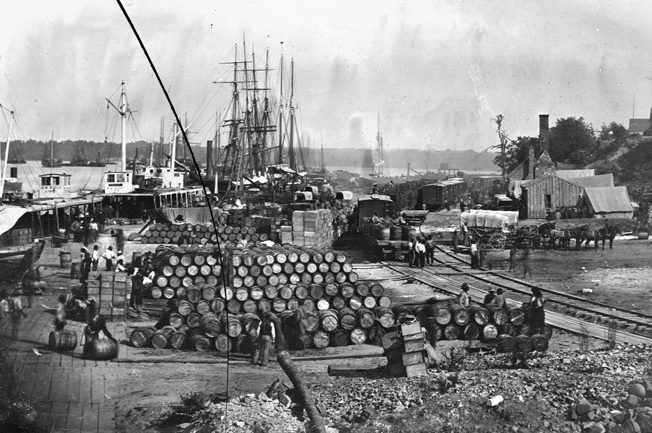

The institutions that were most vulnerable to corruption during the war were those with the responsibility of supplying Union armies in the field. As ordnance and munitions contracts poured out of Washington, production of iron, brass, and bronze weapons proceeded at record levels. Many of the metal foundries were also put to use making rails for the emerging railways. Uniforms, blankets, tents, oil cloth, wagons, chemicals, and ships were all in high demand, and there were plenty of willing men in the North to fill the orders. What Northern manufacturers lost from their Southern markets they more than made up for through government contracts. The loss of Southern markets did have an impact on the textile industry of the North, since other means of acquiring cotton were necessary. These contracts not only provided commerce for small Northern companies, but also opened up the national market.

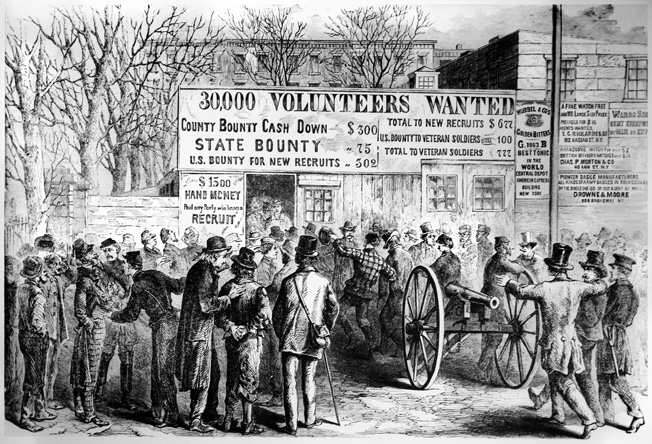

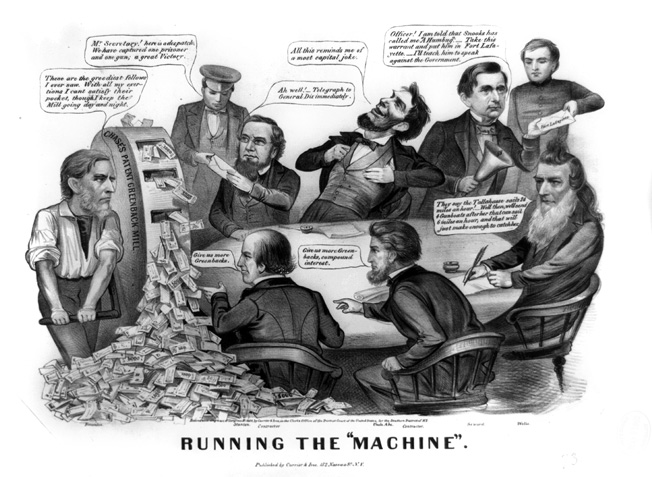

At the beginning of the war, unscrupulous wheelers and dealers swooped into Washington, drawn by unbridled profits from government contracts. The initial rush of raw recruits to answer President Abraham Lincoln’s call for 75,000 volunteers to put down the rebellion was accompanied by a similar rush of businessmen eager to nab government contracts. An army of lobbyists, contractors, and speculators, in the words of one historian, “hurried to the assault on the treasury, like a cloud of locusts. They were everywhere; in the streets, in the hotels, in the offices, at the Capitol, and in the White House. They continually besieged the bureaus of administration, the doors of the Senate and House of Representatives, wherever there was a chance to gain something.”

Keeping the Growing Union Army Supplied

The start of the war was marked by official confusion as well as corruption. With more than 700,000 men in uniform by early 1862, the efforts to adequately supply them were woefully slipshod. Indiana Governor Oliver Morton voiced the frustrations of many Northern governors at the government’s faulty administration of supplies. “Twenty-four hundred men in camp and less than half of them armed,” he fumed. “Why has there been such delay in sending arms? No officer here has yet to muster troops into service. Not a pound of powder or a single ball sent us, or any sort of equipment. Allow me to ask what is the cause of all this?”

Brigadier General Ulysses S. Grant, then commanding the Union camp at Cairo, Illinois, echoed the criticism. “There is a great deficiency in transportation,” said Grant. “I have no ambulances. The clothing received has been almost universally of an inferior quality, and deficient in quantity. The arms in the hands of the men are mostly the old flint-lock repaired. The Quartermaster’s Department has been carried on with so little funds that Government credit has become exhausted.” Lincoln ruefully conceded as much in his annual July 4 message to Congress. “One of the greatest perplexities of the government,” said the president, “is to avoid receiving troops faster than it can provide for them.”

In the sprint to supply the first volunteer soldiers, many less than acceptable products were sold to the government. Although many of the poorer quality items were passed because of sheer haste or carelessness, many more were okayed due to the bribery of government officials at every level. Large contractors would take the high-priced orders they received from the federal government and subcontract them to smaller companies for lesser prices, still making a large profit without actually producing any goods themselves. For example, the Sibley, Tyler, Laugham and Dyer Company was offered a contract of eight cents per pound of cattle, which it then subcontracted to Williams and Alerton for six and a half cents per pound, making a profit of more then $32,000 without moving a single head of cattle.

Corruption at the Highest Levels

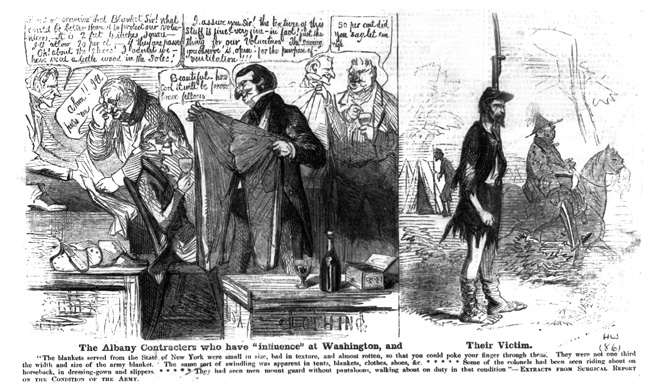

Many high government officials, including Maj. Gen. John C. Fremont, head inspector George Updyke, and Secretary of War Simon Cameron, were later exposed for allowing or encouraging this sort of behavior, but dozens of lesser officials partook in the thievery unmolested. The New York-based company Brooks Brothers produced pocketless, buttonless, and overall inferior-quality pants but somehow still received a government contact to do so. Even rejection did not sway contractors from their dealings. An arms manufacturer once bribed a government official with $10,000 to approve a pistol that shortly beforehand had been deemed unfit for service by the chief of ordnance.

The federal government was cheated on many types of items. In September 1861, Fremont commissioned a fort to be built in St. Louis. The majority of the fort had already been built, but a separate builder received $150,000 for the seven days of work that it took to complete the fort. Quartermaster General Robert Allen was able to catch the closing stages of this deceit and stop another $60,000 from being paid. Animals were also the subject of corruption. The government once bought 411 horses from contractors in St. Louis—76 were in working condition, but all but five were too sick, worn out, or old to be used. The other five were already dead. Another $40,000 was lost on the transaction.

Secretary of War Cameron played a large part in crippling the Union war effort. He commissioned his good friend Alexander Cummings, whom he described as “a capital man,” to buy supplies for the War Department. Cummings did purchase some military-related items, including completely unserviceable carbines for $15 apiece, but he also spent more than $21,000 on such debatable items as herring, porter, ale, straw hats, linen pantaloons, and 23 barrels of pickles for the soldiers. Union supply trains were often needlessly rerouted through Cameron’s home state of Pennsylvania on the flimsiest of excuses, further lining the pockets of his political allies.

One-Fourth of Government Spending Lost to Corruption

Individual Northern states attempted to take up much of the slack left by the inefficient national government. State legislatures appropriated funds to equip and supply regiments at state expense, and governors sent private purchasing agents to Europe to bid for surplus arms. Contracts were made with local textile mills and shoe factories for better uniforms and shoes.

Neither the citizens back home nor the government in Washington were completely oblivious to the fraudulent practices. After Lincoln summarily got rid of Cameron, shipping him off almost literally to Siberia by making him ambassador to Russia, a special Congressional committee was organized to investigate the government’s dealings with private contractors. This committee found that the Colt firearms company was selling revolvers for $25, while the normal asking price was less than $15, providing the company with a tidy profit of $325,000 in one year alone. At the same time, Remington was producing a more or less equal quality revolver for $15, but received only one-sixth the of the volume of government orders that Colt enjoyed.

By the end of the committee’s investigation, it was estimated that fully one-fourth of the government’s spending had been lost to fraud. The blame was hard to place, however. The inspectors blamed the contractors for providing false samples, while the contractors claimed the samples were genuine and blamed the inspectors for approving them in the first place. But even if there wasn’t always someone specific to take the blame, there were still consequences. Eventually, much of the corruption ended after the removal of Cameron and the subsequent appointment of Edwin M. Stanton as secretary of war. Stricter regulations were put in place for approving government contracts, and canny contractors had to adjust their dealings in light of the changed circumstances. Stanton chose a new and industrious quartermaster general, Montgomery C. Meigs, who before the war had overseen a number of large government construction projects, including the building of the new Capitol dome and the Potomac Aqueduct. Meigs immediately instituted a system of competitive bidding, while administering the outlay of some $1.5 billion—one third of the government’s entire war budget.

Corruption, of course, did not stop altogether because of the new measures, but it was severely limited. Later in the war, under the new regulations, a few contractors tried to make money off the government by changing the ratio of corn to oats in horse feed. Assistant Secretaries of War Charles Dana and Peter Watson caught the practice and were able to put an end to the misconduct, saving the government more than $60,000 in feed costs.

No Uniformity With Uniforms

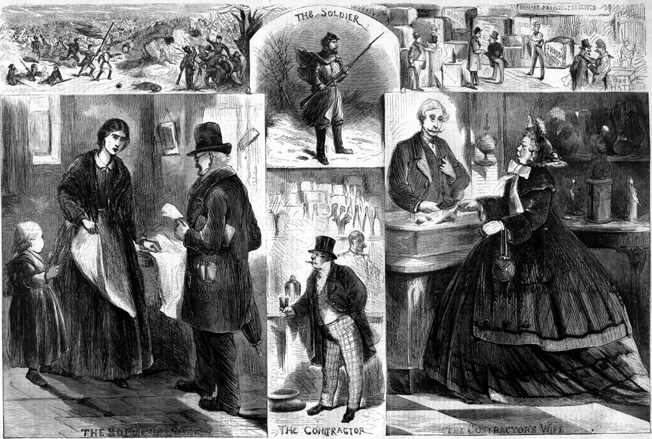

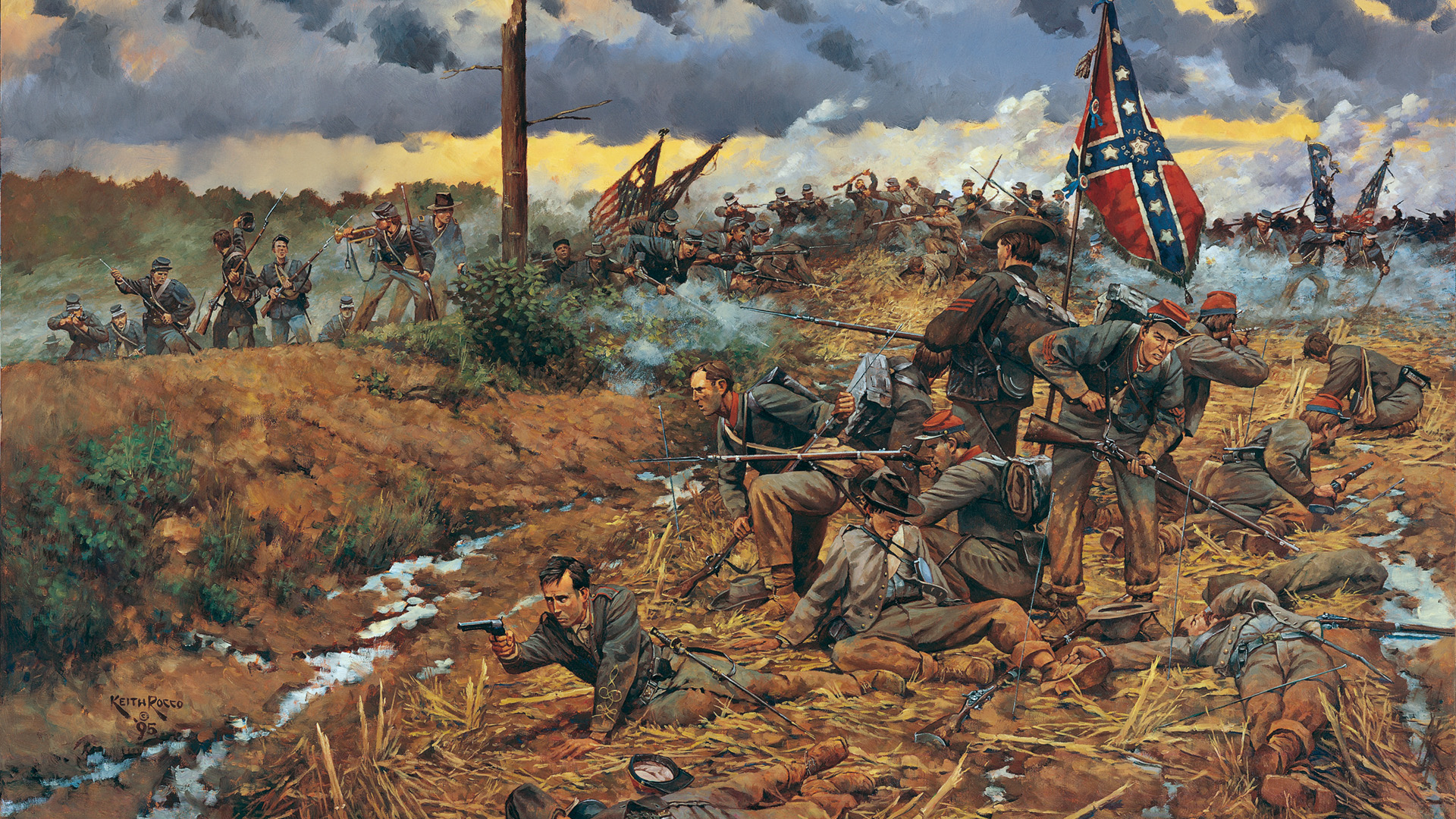

The major consequence to all the double dealing and corruption was the unnecessary loss of life among Union soldiers because of the poor quality of their equipment and uniforms. Because the individual states had fewer men to equip than the national government, they were able to provide quality uniforms to their volunteers. The problem at first was that there was no uniformity between units, and different units received and wore a variety of different colored uniforms. Early in the war, for instance, Massachusetts and Pennsylvania regiments wore blue, Wisconsin, Iowa, and Vermont regiments wore gray, Minnesota regiments wore black trousers and red flannel shirts, and some New York regiments wore the famous Zouave outfits of baggy red pants, purple blouses, and red fezzes. Said one historian with little exaggeration: “The Union forces gathering in Washington looked like a circus on parade.”

Eventually, all Union troops would receive the traditional blue trousers and coats. The government-issued uniforms were known to be of inferior quality. When it came time to trade in their state uniforms, many units refused. During the First Battle of Bull Run, several units came under fire from their fellow Union soldiers because they were wearing gray uniforms. A similar situation was present at the Battle of Cheat Mountain, when Ohio troops killed or wounded several Indiana soldiers due to a case of mistaken identity.

There were other hardships besides the danger of being shot by one’s own side in battle. In the early years of the war, overcoats were in short supply, and those that were available were of such poor quality that it was almost useless to wear them. During the winter months, many Union soldiers suffered from frostbite and died due to the excessive cold. “Lincoln, look here,” a man in the so-called “Ragged-Assed 2nd Wisconsin” called to the president during a parade. “Here is a specimen of the soldiers! Give us good guns and respectable clothing and there will be no trouble.”

The Days of Shoddy

Northern novelist Henry Morford, himself a Union Army veteran, issued a sweeping indictment of government practices in a novel that gave a new word (or at least a new usage) to the English language: shoddy. In his scathing 1864 novel The Days of Shoddy, Morford defined the word as “a wide and disgraceful synonym for the miserable pretense of patriotism—shoddy coats, shoddy shoes, shoddy blankets, shoddy tents, shoddy horses, shoddy arms, shoddy ammunition, shoddy boats, shoddy beef and bread.” Charging that government officials had been “fearfully weak if not actually sharing dishonest profits with contractors,” Morford said the fraudulent practices “began with the beginning and it is evident that they will not end until the close. The leech has fastened upon the blood of the nation, and it will not let go its hold until the victim has the last drop of blood sucked away.”

Morford was relentless in his indictment. “Every shoddy suit, every defective blanket, and every pair of shoes with the soles pasted to the uppers has been the means of making a Union soldier suffer what he need not have suffered in the chances of war,” he wrote. “Every mouldy biscuit or parcel of gangrened beef has been a bid for sickness in the field, or fever, disease and death in the hospital. Every defective arm, every sawdust shell and every worthless horse has left him at the mercy of a fierce and unscrupulous enemy. Every dollar swindled from the public purse has been subtracted from the very lifeblood of the nation. Every swindling contractor has been a murderer.”

Civilian Sutlers of the Civil War

During the first months of the war, while the federal government was struggling to supply its recruits with weapons, it resorted to buying outdated Austrian models, flintlock muskets, or Belgian rifles instead of the higher quality Springfield or English-made Enfield rifles. Some soldiers deserted rather than go into battle with such arms. Others stayed faithful and paid the ultimate cost for their fidelity. When a piece of equipment would break, the cost of repairing or replacing the piece would come out of a soldier’s pay. For some this meant not being able to send money back home to support their loved ones.

When the men were given food that had spoiled long before the government even bought it, they would either starve or, like with their clothing, pay privately for extra food. Satirizing the situation, a cartoon in Harper’s Weekly portrayed a fat contractor and a ragged soldier. The contractor asks the soldier: “Want beefsteak?” The soldier replies: “Good gracious! What is the world coming to? Why my good fellow, if I get beefsteak, how on earth are contractors to live? Tell me that.” The answer was implied.

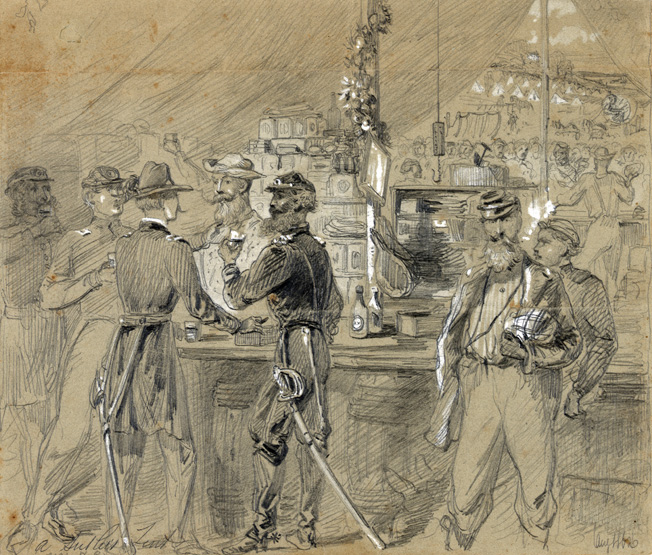

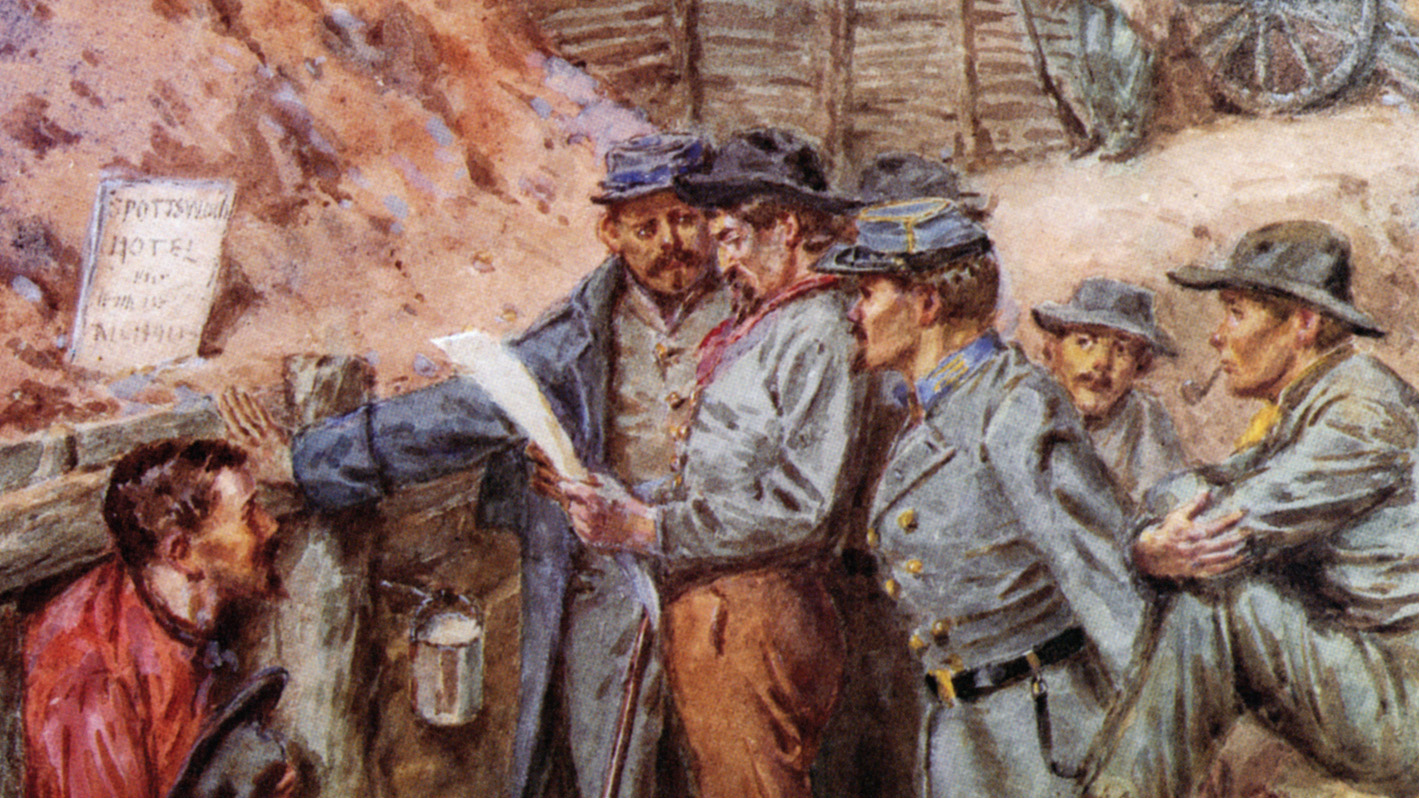

In the absence of effective government supplies, the soldiers often turned to civilian sutlers—private peddlers who held official licenses to travel with the armies and, in the words of the U.S. Articles of War, “supply the soldiers with goods and wholesome provisions or other items at reasonable prices.” The vast majority of sutlers paid little attention to army regulations, particularly the ones limiting the prices they could charge for their goods. A correspondent for the Pennsylvania Press estimated that a typical sutler charged five times an item’s usual cost. It was a seller’s market. One Massachusetts soldier noted that the sutler in his camp made about a 300 percent profit, and another Union soldier claimed, “Our sutler cheats us terrible—but he is a necessary evil.” Still another bluecoat noted, “Our sutler is such a crooked snake, I hope he gets smashed out of business—but not until I’m gone from here.”

Sutlers’ supplies fell into two general categories, “necessaries” and “non-necessaries.” The first category meant primarily clothing and food, including replacement articles of official clothing and such non-essential articles as shoestrings, suspenders, gloves, extra socks, and handkerchiefs. There was a lengthy and comical debate about whether tobacco constituted a necessary or unnecessary item. Many Union doctors sided with the smokers, believing that the smoke from cigars and pipes helped keep down mosquitoes and malaria and was also useful in treating diarrhea and chronic fatigue. Congress, in its considered wisdom, refused to approve an official tobacco ration. Accordingly, all sutlers carried pipes, chewing tobacco, cigars, snuff, papers, and matches. A plug of tobacco could cost as much as a half-month’s pay.

Food items varied at different times and locations but generally included fresh and preserved fruit, fresh and smoked meat, crackers, coffee, molasses, rice, potatoes, cheese, and butter. Also ruled essential, at least early in the war, was the sale of intoxicating beverages, whose medicinal purposes were highly touted by the soldiers. Patent medicines were also carried, sporting such colorful names as Carminative Balsam (“a cure for every ill known to man”) and Redding’s Russia Salve, which claimed to be equally effective for consumption and foot itch.

“There Was Never So Glorious a Cause So Poorly Served”

Perhaps the most tangible effect that corrupt business practices had during the Civil War was the extreme loss of money the government suffered because of the widespread fraud. It was later determined that fully one-fourth of the government’s spending had been lost through fraud. In the first year of the war alone, $50 million was spent for general sustenance of the soldiers, and another $50 million for quartermaster’s supplies, where much of the corruption occurred. By the end of the war, those figures had risen to $369 million and $678 million, respectively. With the cost of moving and packing all these supplies, the various branches of government spent approximately $750 million dollars during the war. A great portion of that money was handed over to unscrupulous contractors.

“There was never so glorious a cause so poorly served, so utterly ruined through the instrumentality in about equal degrees of incompetence and knavery,” said Massachusetts Senator Henry Dawes. It seems like a fair assessment. While a contractor raising the price of his caps an extra couple of dollars did not have nearly as much impact on the war as the battlefield ineptitude of Maj. Gen. George McClellan, economic corruption did affect the way the war was carried out. And as with all wars, it was the common soldier who suffered the greatest consequences and ultimately paid the highest price.

Great Article!

I whole-heartedly agree with your findings.

I would like to ask about a possible source for the comment “A similar situation was present at the Battle of Cheat Mountain, when Ohio troops killed or wounded several Indiana soldiers due to a case of mistaken identity.”

Anything you can cite would be helpful

R.S. Burk

If the Union was so corrupt… why would anyone ever want to succeed from it??

Hmmm….

Because the south was just as corrupt if not more so

Brooks Brothers shame on you!

About the only thing that saved the North was the absence of any goods, shoddy or otherwise, for much of the Southern armies. Funds were extremely scarce and manufacturing capacity was a small fraction of that of the North. Blockade runners made an effort to bring in critical items but a large proportion were captured or sunk. Note: It was not until the Spanish-American War that the Sutlers were abolished and military post exchanges established.

And on top of that many planters refused to grow food stuffs in favour of cash crops like cotton, tobacco, indigo and the like. Had the greed not been so prevalent even a small section of land devoted to food crops from each planter would have filled southern bellies and fed horses and mules. Every little bit helps as they say.

Wasn’t Shoddy the name of a contractor that supplied inferior goods?