By William E. Welsh

By mid-afternoon on September 17, 1862, the Army of the Potomac and the Army of Northern Virginia were locked in mortal combat on the rolling hills overlooking the sluggish waters of Antietam Creek in northwestern Maryland. The two sides had been fighting each other since daylight in what would turn out to be the bloodiest one-day battle of the Civil War. As the sun began its slow descent in the sky, Confederate General Robert E. Lee feared that victory lay within his foe’s bloodied but emboldened grasp.

Throughout the day, Maj. Gen. George McClellan’s Union forces had steadily bled Lee’s much smaller army of its reserves. Increasingly desperate, Lee had pulled one unit after another from his right flank to strengthen other sectors of his hard-pressed line, and now the Federals were massing for a final assault on his weakened flank. When they struck, Lee feared that there would not be sufficient numbers of Confederates to hold them back. The army’s last line of retreat would be severed, and the war in the East would be as good as over in one fell swoop.

Lee had one last card to play, however. His ace in the hole was Maj. Gen. Ambrose Powell Hill’s Light Division, which was somewhere on the road between nearby Harpers Ferry, Va., and Sharpsburg, the small Maryland town around which Lee’s line of battle was tightly wrapped. One of Lee’s last acts on the eve of battle had been to send Hill an urgent dispatch ordering him to rejoin the army immediately. (Read more about the battles and events that defined the American Civil War inside Military Heritage magazine.)

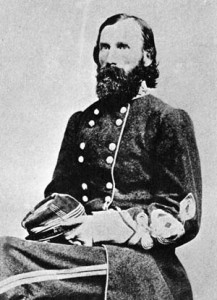

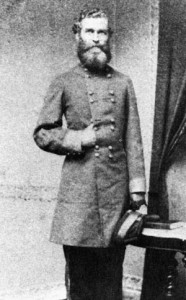

Ambrose Powell Hill and His Light Division

Hill received Lee’s dispatch at 6:30 am. Leaving one brigade behind to complete the parole of the last of the 11,000 Federal prisoners captured at Harpers Ferry, Hill quickly put his five other brigades on the road to Sharpsburg. As the Federals began their final advance on his lines, Lee had no idea where Hill was or, worse yet, when he would arrive. At his headquarters on the outskirts of Sharpsburg, the Confederate commander anxiously watched and waited for Hill’s appearance.

Hill and several members of his staff rode breathlessly into Lee’s headquarters at 2:30 pm. A man of slight build with a bright chestnut-red beard, Hill was affectionately known as “Little Powell” to the Confederate high command. At the time of the battle, he was the youngest major general in the Confederate Army. Having shed his jacket in the heat, Hill was easily identified by his troops on the march by his famous red “battle shirt,” which he wore whenever the day promised to produce a good fight. After a quick greeting, Hill informed Lee that his infantry was at that very moment fording the Potomac River three miles away and would soon be on hand. When it arrived on the battlefield, Lee instructed, the reinforcements should support the right flank. Having received his orders, Hill and his staff returned to the infantry column.

At 3 pm, Union Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside’s IX Corps began advancing on a broad front toward Sharpsburg. The Federals outnumbered the Confederates in that sector three-to-one. If Hill’s troops didn’t arrive soon, the Southern right flank would collapse and disintegrate. The battle would be lost.

Lee’s eyes were riveted on the Harpers Ferry Road south of Sharpsburg, where the battle was intensifying and the Light Division was expected to arrive any minute. When he spied a column moving from the southeast, Lee called to an artillery officer nearby.

“What troops are those?” Lee asked.

The officer offered Lee his spyglass. “Can’t use it,” Lee said, raising his bandaged hands. The general had been thrown from his horse at the start of the campaign and had broken one of his hands and sprained both wrists. The officer raised his glass and focused the lens on the column. “They are flying the United States flag,” he said.

Lee pointed to another column to the southwest and asked the same question. The officer trained his glass on the new column. “They are flying the Virginia and Confederate flags,” he said.

Lee sighed with relief. “It is A.P. Hill from Harpers Ferry.” If the Light Division could get into battle quickly enough, it might be able to save Lee’s army from what a few minutes before had seemed like certain destruction.

The Dependable A.P. Hill

Lee had little need to worry about whether Hill would arrive in time. In the half-dozen major engagements since the beginning of the war in which Hill had led troops, he had shown himself to be a prompt, dependable, and hard-hitting commander. He pushed his troops hard, followed orders well, and never lost his cool in battle. A fighter by nature, Hill had conducted only one major defensive action since the war began. If Lee could rely on any of his division commanders to launch a successful counterattack, it was Ambrose Powell Hill.

Hill was bred from the same colorful cavalier Virginia stock as such other well-known Confederate officers as Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart. Born in Culpeper on November 9, 1825, Hill entered the United States Military Academy at West Point in 1842 at the age of 16. In the kind of ironic twist that typified the Civil War, he would become closely acquainted with the two individuals who would be his principal opponents at the Battle of Antietam. His first-year roommate was George McClellan. Although Hill should have graduated the same year as McClellan, he was held back a year because of a chronic illness. Thus, Hill and his close friend Ambrose Burnside graduated 15th and 18th, respectively, in the Class of 1847.

In August 1847, Hill received orders to report for service with the U.S. 1st Artillery Regiment in Mexico. He arrived at the port of Vera Cruz after the regional capital had fallen and participated in a limited fashion in two of the closing battles of the struggle. When the Americans sacked the town of Huamantla, Hill observed firsthand the great harm that volunteers were capable of doing if not properly disciplined. This experience deeply ingrained itself on the young lieutenant and afterwards would inform the authoritarian way in which he led those who served under him.

After the Mexican War, Hill served a year of garrison duty at Fort McHenry, Md., before shipping out with his unit to western Florida, where he participated in the ongoing suppression of the Seminoles. After five years of service in Florida, Hill transferred to the U.S. Coast Survey, in which post he was serving when the first seven southern states seceded from the Union following the election of Abraham Lincoln. Despite being urged by his comrades to remain in the service, Hill resigned in February 1861 and returned to his home state, hoping to receive an appointment commensurate with his extensive military experience.

Much to his chagrin, Hill was passed over for a generalship by Virginia Governor John Letcher and instead was named colonel of the 13th Virginia Infantry. The regiment comprised 10 companies, all drawn from Virginia with the exception of one company from Baltimore. Hill began training the regiment at Harpers Ferry, where it was part of General Joseph Johnston’s Army of the Shenandoah. Little Powell drilled his men several times a day. His training was so effective that Johnston commended the 13th Virginia for its “veteran-like appearance.” When Johnston received orders from Richmond on July 17 to move his army to Manassas to support Brig. Gen. Pierre G.T. Beauregard in a major battle then taking shape along the banks of Bull Run Creek, the 13th Virginia traveled by train to Manassas Junction, but saw no action at the ensuing Battle of First Manassas.

First Battle at Williamsburg

In February 1862, Hill was appointed brigadier general commanding the First Brigade of Maj. Gen. James Longstreet’s Second Division. When McClellan, the new commander of the Army of the Potomac, landed in April with 120,000 Federal troops at Fort Monroe at the tip of the peninsula between the James and York Rivers, Hill’s brigade marched to the aid of Maj. Gen. John Magruder, who had established a defensive line across the peninsula’s lower portion to thwart the Federal advance.

Hill’s first major action in the Civil War occurred on May 5 at Williamsburg. Longstreet ordered him to drive back Brig. Gen. Joseph Hooker’s Federal division. Hill led his men against a strong enemy position in thick woods on the outskirts of Williamsburg. The two sides fought at close range in the driving rain throughout the afternoon. Just before nightfall, Hill’s troops launched a successful charge that routed Hooker’s troops and resulted in the capture of 160 prisoners, seven flags, and eight artillery pieces.

On May 27, in recognition of his role at Williamsburg, Hill was promoted to major general. He had risen from colonel to major general in just 90 days.

Hill called his new command the Light Division, a name that stuck with it throughout the war. The division, which comprised six brigades, was actually the largest in the Confederate Army, and Hill gave no explanation for the name he had chosen. In the absence of such an explanation, the nickname came to be associated with his troops’ ability to march fast and take little more than their rifles, cartridge boxes, and haversacks into battle. Division Private Wayland F. Dunaway recalled later that “the name was applicable, for we often marched without coats, blankets, knapsacks, or any other burdens except our arms and haversacks, which were never heavy and sometimes empty.”

Defensive Clash at the Battle of Second Manassas

Hill solidified his growing reputation as an aggressive general during the Seven Days’ Battles that followed. When Johnston was wounded at Seven Pines, Robert E. Lee assumed command of the Confederate army around Richmond. Shedding Johnston’s defensive mindset, Lee at once sought to take the offensive and drive the Federals away from the city. In his first battle as a division commander, Hill launched a costly frontal attack on June 26 without support against Federals entrenched behind Beaver Dam Creek. Maj. Gen. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson was partly to blame for the debacle by failing to carry out an expected flank attack. Perhaps because Hill had shown initiative, which was notably lacking in some of his fellow generals, Lee did not rebuke him for his rashness.

The pattern of piecemeal attacks continued throughout the Seven Days. Whether from fatigue or a lack of familiarity with the countryside, Jackson repeatedly failed to strike at the time and place instructed by Lee. At Gaines’ Mill on June 27, Hill’s men were badly mauled when they attacked entrenched Federals on a rise behind Boatswain’s Swamp. Hill lost more than 2,600 men in the battle. Despite these defeats, Hill showed a knack for carrying out orders and an ability to pin down large bodies of Federal troops and make it difficult for them to disengage. His star continued to rise.

The Light Division’s marching skills were put to the test in the next phase of the campaign when Hill’s troops made a forced march to attack McClellan’s army on its retreat to the James River. At Frayser’s Farm on June 30, Longstreet advanced first. When the Federals threatened to outflank Longstreet, Hill’s division joined the battle. The Light Division drove the enemy back and captured 18 guns.

Although officially part of Magruder’s command, Hill’s division had been attached to Longstreet for the last part of the Seven Days’ Battles. Following the campaign, Lee transferred Hill to Jackson’s command for a new campaign unfolding in central Virginia against Maj. Gen. John Pope.

Because Jackson had failed to support him throughout the Peninsula campaign, it was with some reservation that Hill joined him at Gordonsville.

A twist of fate put Hill’s division in the rear on the march to Culpeper, which led to the Battle of Cedar Mountain. When Jackson’s left flank collapsed on the afternoon of August 9, Hill immediately stabilized the main Confederate line with his troops. Once it was stabilized, the Light Division advanced and swept the field. Although Jackson was too proud to admit it, Hill had saved his skin at Cedar Mountain.

That same month, Hill anchored Jackson’s left flank behind the unfinished railroad bed on the old Bull Run battlefield. The Battle of Second Manassas was Hill’s first defensive fight. With three brigades forward and the other three held in reserve, Hill repulsed six separate attacks on August 29. When the Federals pierced his line, he skillfully shifted his forces to close the breach. He showed a remarkable ability to coordinate movements among his units in the heat of the two-day battle. He received rare praise from the prickly Jackson for repulsing superior enemy numbers.

The Confederate Maryland Campaign

An ongoing dispute between Hill and Jackson over marching procedures, which could be traced back to Cedar Mountain, reached crisis proportions at the outset of the Maryland campaign, Lee’s ambitious late-summer invasion of the North. Jackson required that the troops begin marching before sunrise and rest 10 minutes every hour. When one of Hill’s brigades was not ready to march from Dranesville, Va., to the Potomac River on September 4, the first day of the campaign, Jackson’s mood turned sour. To make up for lost time, Hill decided to forego Jackson’s mandatory rest period each hour. When Jackson halted one of Hill’s brigades without consulting him, Hill offered his sword to Jackson in disgust. Jackson immediately placed him under arrest, turned command over to Hill’s senior brigadier, and ordered Hill to march at the rear of his division.

After two days in Frederick, Md., Lee divided his command into three parts. Jackson would command the part of the army entrusted with the capture of the Union garrison at Harpers Ferry, which lay across the Confederate line of retreat. Sensing that battle was imminent, Hill requested through a member of Jackson’s staff to be temporarily reinstated to his command for the fighting that lay ahead. Without hesitating, Jackson agreed.

Jackson and his forces drove a contingent of Federals from Martinsburg on September 13. The retreating Federals took refuge with the larger force based in Harpers Ferry. Next, Jackson divided his command into three separate forces to invest Harpers Ferry. Lee’s schedule for the campaign allowed no time for a protracted siege, so Jackson moved quickly to attack. While other units occupied the heights across the Potomac and Shenandoah rivers from the town, Jackson’s corps bottled up the town on September 14 by occupying the neck of land behind Harpers Ferry.

The Light Division, which held the Confederate right flank along the Shenandoah River, drove the Federals back and captured the high ground, where Hill, the old artillery officer, carefully placed the division’s guns.

At first light the following day, southern guns began shelling the town from three sides. After an hour-long bombardment, the Federals replied with desultory fire. At that point, Jackson ordered the Light Division forward again. At 9 am, the Federals waved the white flag and surrendered to Jackson. The Confederates captured 11,000 prisoners, 12,000 rifles, 70 guns, and countless supplies.

Because the Light Division had borne the brunt of the fight, it was given the honor of paroling the Union prisoners. During their two days inside the town, many of Hill’s soldiers exchanged their ragged clothes for parts of new Federal uniforms in storage. Since Lee needed all available Southern troops at his new position at Sharpsburg, plans were made to parole the prisoners and permit them to march home, provided they not rejoin the Union Army until they were properly exchanged. Jackson’s other two divisions departed for Sharpsburg the night of September 16. The next morning, Hill received Lee’s dispatch instructing him to join the army immediately for a major battle.

“Speed the March, Close Up, Close Up!”

After receiving Lee’s dispatch at daybreak, Hill donned his familiar red battle shirt, buckled on his dress sword, and began issuing orders to his brigadiers for a forced march. Telling Colonel Edward Thomas to remain with his brigade at Harpers Ferry to complete the surrender, Hill ordered Brig. Gen. Maxcy Gregg to get his troops on the road immediately. Gregg’s South Carolinians were on the road within the hour. Rather than sending his division by the shortest route to Sharpsburg, on the north bank of the Potomac, Hill chose instead to send his troops on a route that was slightly longer on the south bank to avoid running into any stray Federal units that might delay him or bar him from reaching Lee.

Spirits were high in the ranks as the division marched north along a narrow dirt road that led toward Shepherdstown, where it would ford the river. The men in the column were well fed and wearing new clothing taken from the vast stores at Harpers Ferry. As they marched, the men could hear the boom of cannon ahead in the distance. The troops in the front were told to set a brisk pace. The shout frequently heard up and down the line was, “Speed the march, close up, close up!” Hill rode back and forth along the column prodding stragglers with the point of his sword.

The column stopped only two or three times for just a few minutes to allow the men to catch their breath before resuming the march. Such stops were not enough to keep dozens of men from dropping out of the ranks from exhaustion. Hill and his officers were able to produce a near superhuman effort from the men by telling them that their beloved commander Lee was counting on them.

When Hill’s troops reached the river, they began crossing immediately. Holding their muskets and cartridge boxes high above their heads, they plunged into the water, doing their best to maintain their balance while walking over jagged ledges on the river bottom that ran perpendicular to the swift current.

The high expectations that Hill had for himself and his men were readily apparent in an episode that occurred after the division had forded the river. When he spied a second lieutenant crouching in fear behind a tree, Hill rode over to the officer, demanded his sword, and broke it across the man’s shoulder. Without speaking a word, Hill returned to the column. When he reported to Lee, he would have in hand a force of some 1,900 soldiers to put into battle.

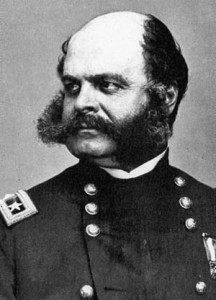

Fighting at Burnside’s Bridge

Meanwhile, Hill’s old roommate, George McClellan, had sent orders to their mutual friend Ambrose Burnside, instructing him to take the lower bridge, known as Rohrbach Bridge, over Antietam Creek. In his battle plan, McClellan envisioned that Burnside would cross the bridge in the morning and be in position on the west bank of the Antietam by noon to exploit the costly advantages won by earlier Federal attacks on the Confederate left and center.

But Burnside was not in a cooperative mood. Having been stripped of Hooker’s corps following the Battle of South Mountain, where he served as commander of the army’s right wing, Burnside was having a hard time adjusting to the role of a mere corps commander. In fact, he still fancied himself a wing commander, and therefore had placed Brig. Gen. Jacob Cox in direct command of the IX Corps. Even after receiving multiple orders from McClellan ordering him to advance, Burnside made only a half-hearted attempt to get his men across the creek. After several repulses, two regiments of Brig. Gen. Edward Ferrero’s brigade of Brig. Gen. Samuel Sturgis’s division finally carried the bridge at 1 pm.

Although IX Corps would make its attack alone, unsupported by any other elements of the Union Army, it had enough manpower to wreck the Confederate right flank if handled properly. At his disposal, Burnside had four divisions numbering about 8,500 men. If he could get his men into battle quickly, the pressure he applied to Lee’s right flank might be enough to make the entire Confederate position implode. But once across the creek, Burnside squandered the opportunity for surprise by taking two hours to replenish his troops’ ammunition and shake them into a new line of battle before advancing.

Once under way, the Federals found the going tough. The terrain south of Sharpsburg rose gradually from Antietam Creek to the Harpers Ferry Road. Between the creek and the north-south road, the ground was wildly uneven and characterized by steep ravines that afforded a marked advantaged to whomever occupied the higher portion of a given slope. Hard by the road, which ran from the lower bridge to Sharpsburg, were two farms. At the time of the battle, the farms on the north and south sides belonged to Joseph Sherrick and John Otto, respectively. The crux of the battle between Hill and Burnside would mainly occur on the farm belonging to the latter, notably in his 40-acre cornfield. The fields were divided by stone and rail fences that would provide a distinct advantage to whichever side reached them first.

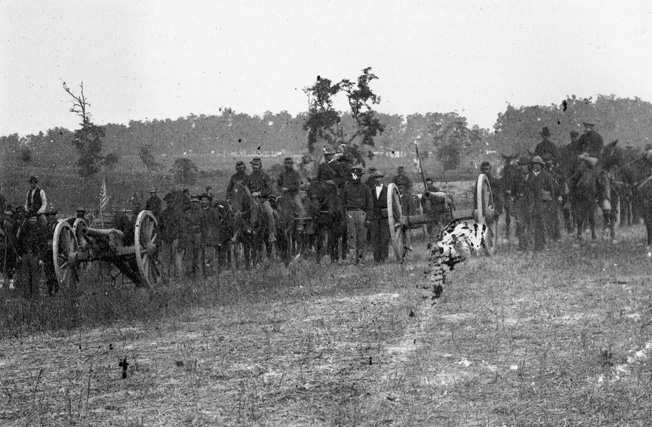

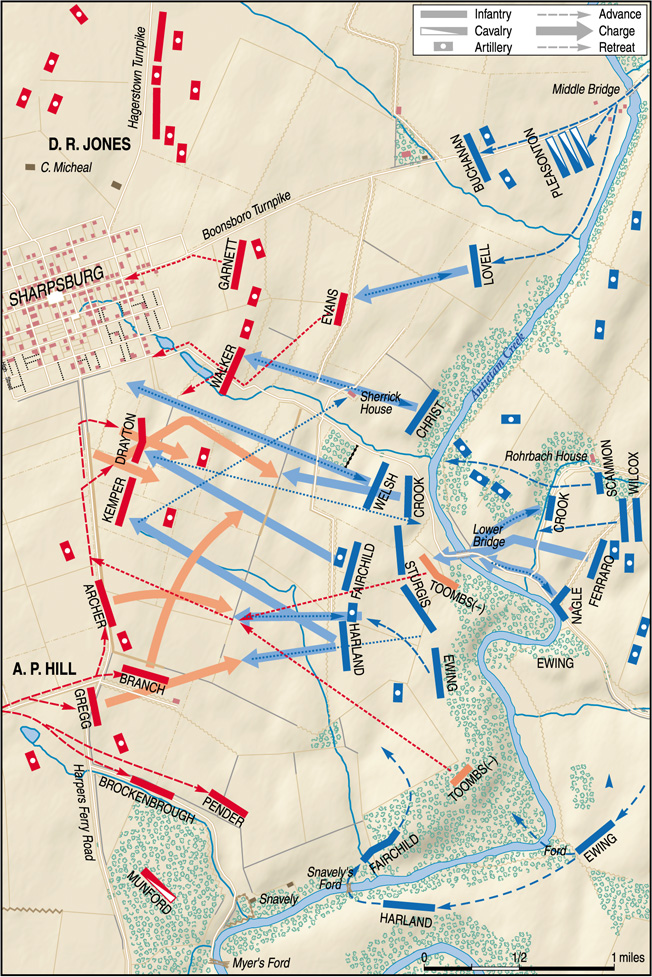

IX Corps advanced in three lines at 3 pm. On the left was Brig. Gen. Isaac Rodman’s division, which had crossed two miles downstream at Snavely’s Ford; on the right was Brig. Gen. Orlando Wilcox’s division. Directly behind them was Cox’s Kanawha Division under the command of Colonel Eliakim Scammon. Sturgis’s division, which bore the brunt of the attack on the bridge, thereafter to be known as Burnside’s Bridge, formed the reserve. The Federal infantry not only had the support of the long-range guns on the east bank of the Antietam, but also close artillery support from four batteries comprising 22 guns that followed the infantry over the bridge.

The Confederates’ Battered Ranks

Facing them were the badly depleted ranks of Confederate Brig. Gen. David Jones’s division. Down to less than half its original number, the division was all that stood between Burnside and Sharpsburg. Jones had five of his six brigades on hand for the late afternoon fight, having relinquished Colonel George “Tige” Anderson’s brigade to support the Confederate center. By mid-afternoon, each brigade in the division was down to the size of a single regiment.

Despite his paper-thin ranks, Jones enjoyed ample artillery support, thanks to the foresight of Lee and Longstreet. The Confederate high command had assembled 28 guns to support Jones in what would be the last major clash of the day.

More guns would be added to the Confederate defense. Captain David McIntosh, who commanded the first of Hill’s units to arrive on the field, quickly unlimbered three guns from his battery along the Harpers Ferry Road. They soon joined the other Confederate guns in shelling the Federal batteries opposite them.

The Federals, for their part, advanced steadily over uneven ground. The Confederate gunners switched their fire from the enemy batteries to the sea of blue infantry as it drew ever closer. Still, the Union tide surged forth. The Federals drove Jones’s division back into Sharpsburg. Some of his troops shifted to the north side of town, while others entered city streets where enemy shells had set homes and buildings ablaze.

At that moment, Hill’s infantry arrived.

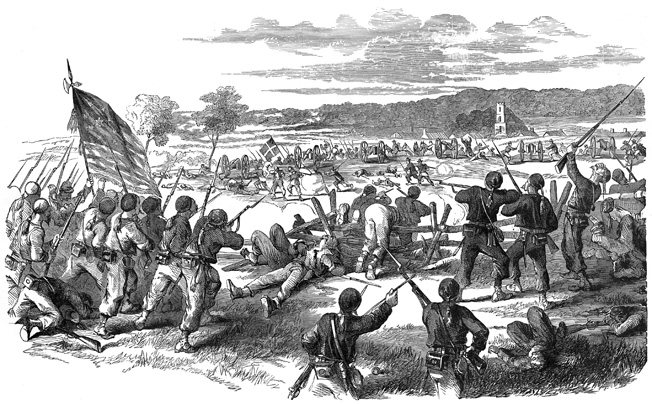

Rebel Yell From the Light Division

Without taking time to reconnoiter the battlefield, Hill threw his troops into the fight at 3:30 pm Gregg’s South Carolinians were first up. Following a quick discussion with Jones, Hill ordered Gregg to relieve Brig. Gen. Robert Toombs’s hard-pressed brigade. His fellow division commander “gave me such information as my ignorance of the ground made necessary,” wrote Hill in his battle report. Armed with the scanty information, Hill committed the first of his five brigades to the battle. With a shout, Gregg’s five South Carolina regiments advanced onto the Otto farm. Hearing Gregg’s men give the Rebel yell as they advanced on the enemy, Jones’s weary soldiers found renewed strength. They weren’t the only ones affected—Lee’s demeanor changed noticeably from fear of defeat to confidence in his army’s ability to withstand the latest Federal assault.

“My troops were rapidly thrown into position, [Dorsey] Pender and [John] Brockenbrough on the extreme right, looking to a road which crossed the Antietam near its mouth, [and Lawrence] Branch, Gregg, and [James] Archer extending to the left and connecting with D.R. Jones’ Division,” Hill wrote afterward.

In addition, Hill oversaw the deployment of his division’s remaining batteries. He ordered Captain Carter Braxton’s battery to a rise on Gregg’s right and the batteries of Captains William Crenshaw and Willie Pegram to high ground on the left, where they would have a wide field of fire.

Clash in the Otto Cornfield

When the Light Division arrived on the field, Colonel Edward Harland’s brigade of Rodman’s division was pushing its way through the large cornfield south of the Otto farmhouse. Harland’s four New England regiments—the 8th Connecticut, 11th Connecticut, 16th Connecticut, and 4th Rhode Island—would face the full fury of the Confederate counterattack spearheaded by Gregg’s veterans. The two brigades collided head-on in the tall corn.

The 8th Connecticut was the farthest forward of Harland’s regiments. Due to a mix-up in orders, it was directed to advance before the other regiments in the brigade. The regiment’s objective was McIntosh’s guns. As the 8th Connecticut bore down on its objective, McIntosh switched to canister. Realizing that if he tried to withdraw his guns in the face of the enemy he would lose his gunners in the process, the cool-headed artillery captain instructed his gun crews to abandon their pieces and retire to the rear. They did so just as the bluecoats swarmed over the three pieces.

Hill assessed the situation from a point along the Harpers Ferry Road. “My troops were not in a moment too soon,” he wrote. “The enemy had already advanced in three lines, broken through Jones’ division, captured McIntosh’s guns, and drove them back pell mell.” Both Hill and his brigadiers felt the weight of the moment and rose to the occasion. “Branch and Gregg, with their old veterans, sternly held their ground, and, pouring in destructive volleys, the tide of the enemy surged back, and, breaking in confusion, passed out of sight,” Hill reported.

At several key moments during IX Corps’ attack, Federal regiments would hold their fire when they saw troops wearing blue uniforms nearby. These units would invariably turn out to be troops belonging to Hill’s division who had appropriated parts of new Federal uniforms to replace the torn and tattered clothing they had been wearing when they captured Harpers Ferry. One such unit was the 4th Rhode Island. Fearing that it might shoot into friendly troops, the regiment momentarily withheld its fire and received a deadly volley from Gregg’s men before realizing its mistake.

Meanwhile, from a strong position behind a stone wall on the Otto Farm, Gregg’s troops unhesitatingly blasted the 4th Rhode Island and 16th Connecticut. The Connecticut unit, a green regiment that had only been in the army for three weeks, had the unfortunate luck to face crack Confederate troops in its first fight.

The well-aimed fire was more than the Connecticut soldiers could stand. The regiment broke for the rear, carrying the 4th Rhode Island along with it. The tragedy was compounded for the Federals when a Confederate sharpshooter fired a round that struck Rodman flush in the chest and left him mortally wounded. Gregg was also struck by a bullet in the hip that knocked him from his horse. When he realized that the bullet had only grazed him, the feisty brigadier returned to his command.

The brigades of Branch and Archer moved to support Gregg. Branch bolstered Gregg’s thrust into the Otto cornfield, while Archer’s troops moved at the double quick along Gregg’s left flank to support Jones’s line, which was fast unraveling as a result of a coordinated Federal assault.

The Loss of a Brigadier

Although Gregg had managed to check Harland’s brigade, three more Federal brigades were closing in on Sharpsburg. By 4 pm, Colonel Harrison Fairchild, commanding Rodman’s other brigade on Harland’s right, smashed the brigades of Brig. Gens. James Kemper and Thomas Drayton and reached the very gates of Sharpsburg.

Just north of Fairchild, the two brigades of Wilcox’s division under Colonels Thomas Welsh and Benjamin Christ were locked in desperate combat with Jenkins’ brigade, commanded by Colonel Joseph Walker. Unlike Kemper and Drayton, Walker was holding his ground by taking advantage of cover afforded by the Sherrick farm buildings and the terrain. His brigade was the last unit left between the Federals and Sharpsburg. With Gregg preoccupied with Harland, Hill ordered Archer’s brigade to charge the enemy.

Strengthened by elements of Jones’s division, Archer’s men overwhelmed the 8th Connecticut and recaptured McIntosh’s guns. The hapless Union regiment lost fully two-thirds of its men before retreating. Next, Archer formed his men into line of battle along the Harpers Ferry Road and advanced east toward Antietam Creek, driving Fairchild before him.

At one point the three Confederate brigadiers—Archer, Branch, and Gregg—were conferring about how best to press the attack on the Federal left flank when a sharpshooter put them in his sites. When his attention was directed to enemy soldiers closing on his flank, Branch raised his glass to have a closer look. At that moment, a bullet tore into his right cheek and exited from the back of his head. The shot killed him instantly. The North Carolinian collapsed near his fellow generals.

The Union Withdrawal

The rout of Harland’s brigade by Gregg’s South Carolinians threw the entire IX Corps offensive into jeopardy. In an immediate sense, it exposed Fairchild’s flank to attack by Hill’s division. For this reason, Cox ordered the withdrawal not only of Fairchild’s brigade, but also Wilcox’s division. Although they were furious at having to give up the ground they had captured, Cox’s subordinates complied with his order. By 4:30 pm, the Federals were in full retreat.

Colonel Hugh Ewing’s brigade of the Kanawha Division fruitlessly tried to plug the gap created by Harland’s troops, who were streaming to the rear. His three Ohio regiments advanced toward Gregg’s position on the Otto Farm. Like the 4th Rhode Island regiment before them, the Buckeyes mistook soldiers wearing blue for fellow Federals. While they held their fire, Gregg’s men blasted their ranks mercilessly, dropping large numbers of Federals. The Ohio troops made a valiant try to wrest a stone wall from Gregg’s veterans, but were forced to fall back with their retreating comrades.

The last major action of the battle occurred when Cox committed a portion of his reserves to stabilize his ranks. He sent forward troops from Sturgis’s command to form a new line he was constructing along the bluffs overlooking the creek. By that point, the Confederates had clearly gained the upper hand. More than 40 Southern guns posted along the high ground around Sharpsburg swept the landscape across which the Federals were retreating. Most of the Union guns on the far bank had run out of ammunition by this point in the battle, and the batteries that had advanced with the infantry found themselves outgunned. The action gradually died out, and both sides were content with their new positions.

The Battle of Antietam: The Greatest Action of Ambrose Powell Hill

Because of the Light Division’s late entrance to the battle, it came away with just 63 killed and 283 wounded from the 1,900 soldiers who participated in the battle.

Hill’s performance at Antietam was nearly flawless. The battle highlighted his best attributes as a commander, most notably his ability to move his troops promptly and motivate them on the battlefield. At Antietam, Hill exhibited a willingness to fight a pitched battle against his foe without second-guessinghimself, unlike many of the Federal commanders he faced that day. At the same time, the battle masked his shortcomings as a commander—his repeated failure to reconnoiter ground before attacking and his bad habit of leaving a gap in his lines for the enemy to exploit when he was on the defensive.

Hill’s performance was not overlooked by Lee or his principal lieutenants at the battle, Jackson and Longstreet. Although Hill had had a falling out of sorts with Longstreet after he left his command earlier that year, Old Pete found it in his heart to mention Hill’s “exemplary” performance in his battle report. He noted that Hill’s Light Division had helped check the advance against his corps in the vicinity of Sharpsburg. “The display of this force was of great value, and assisted us in holding our position,” wrote Longstreet.

Following Antietam, Hill led the Light Division in the famous battles at Fredricksburg and Chancellorsville. After Jackson’s tragic death at the latter battle, Hill was promoted to lieutenant general on May 23, 1863, and placed in charge of the III Corps of Lee’s newly reorganized Army of Northern Virginia. During the army’s second invasion of the North one year later, Hill attacked Federal forces he stumbled upon at Gettysburg, thus helping to ignite that epic battle. Little Powell participated in the Battle of the Wilderness in May 1864, but because of illness was absent from the Battle of Spotsylvania later that month.

Still dogged by chronic illness, Hill participated off and on in the series of battles between Lt. Gen. Ulysses Grant and Lee that culminated in the siege of Petersburg. On April 2, 1865, Hill was convalescing at his temporary residence in Petersburg when news reached him that the Confederate line had snapped. He immediately rode to his troops and was in the process of trying to rally them when he was killed by enemy fire.

With the exception of the fight at Spotsylvania Court House, when he was too ill to lead his troops, Hill fought in every major battle of the Army of Northern Virginia waged by Lee. But his performance at the Battle of Antietam stands as his greatest achievement as a general. To say that Hill single-handedly saved the Army of Northern Virginia that day is an overstatement, but he certainly played a major role in the repulse of McClellan’s much larger Union army. There can be little doubt that Antietam was the Culpeper Cavalier’s finest hour. n

Thank you for this detailed walkthrough of the battle. My grandmother’s uncle fought with the IX Corp under Ewing (30th Ohio Infantry). I had not realized that Hill’s men were dressed in Union-issue uniforms and ask myself if the outcome might have been any different if the Rhode Island, and later Ohio infantry would have recognized Hill’s men as enemy combatants. Small (or not so small in this case) dynamics can shift momentum in one direction or the other.

A tragic day for America. Given present day (post-Trump), it’s clear that in some important respects our civil war did not solve fundamental issues plaguing American life- as evidenced by which states attempted to overturn legitimate election results in 2020.

Although a Confederate victory in the sense that the Union advance was stopped for a time, the action convinced Lincoln that Union troops would fight, especially with good leadership. The president looked West for that leadership and saw Grant at Vicksburg and Ft, Donnellson and moved him to the Army of the Potomac the following year. It also gave him the impetus to proclaim the Emancipation Proclamation on Jan 1, 1863, followed by the recruitment of Black soldiers that year. By 1864, it was clear that despite the initial advantages of the Confederacy, the improved leadership, better logistics and a larger source of manpower of the Union, that eventual victory was assured. Side note: Antietam was the source of the largest number of casualties of the war in a single day.