By David H. Lippman

“It is very difficult to be an openly declared, courageous Nazi today, and to express one’s faith freely,” read the editorial in the Völkischer Beobachter newspaper, which further added, “We have no illusions now.” The official newspaper of the Nazi Party had good reason to sound a fearful note. As dawn broke on March 25, 1945, the British 21st Army Group had hacked a 30-mile-long and seven-mile deep bridgehead over the Rhine River. Operations Plunder and Varsity, Field Marshal Sir Bernard Law Montgomery’s massive set-piece Rhine crossing, had succeeded perfectly at a small cost in Allied casualties: 3,968 for the British 2nd Army and 2,813 for the U.S. 9th Army. In turn, some 16,000 Germans had been taken prisoner. Now, with Germany’s last major barrier breached, there was little to stop Monty’s 20 divisions and 1,600 tanks from fulfilling the Western Allied invasion of Germany, driving deep into the Nazi homeland and the Netherlands.

Even so, the drive would not be easy. First, all the bridges across the Rhine had been blown, and British and American engineers had to replace them with Bailey bridges. Up and down the Wesel bridgehead, sappers and engineers were hard at work. Bulldozers carved out approaches to the riverbank while engineers scrambled with wrenches and iron bars to finish two Bailey bridges. Buffalo amphibious vehicles shuttled back and forth across the river, hauling supplies and troops.

The Soldiers That Crossed the Rhine

British Major Roland Ward helped develop a system using wire ropes to winch tank carriers across the Rhine. The raft was composed of five large pontoons, about 25 feet long and five feet wide, connected with steel panels, with ramps at each end. One raft broke from its moorings. Major Ward commandeered a motorboat to take him out to the raft.

“I jumped on board and found the crew were petrified. Their motors wouldn’t hold, they were drifting down the lines and the next stop was the German lines, you see. The officer, I think, had lost his head a bit. The anchor didn’t seem to hold and the motors didn’t work, but by a bit of luck someone had brought out a rope from the far side and he joined it up to a bulldozer. I thought, if he pulls too hard he’ll break it. So I said, ‘You can direct the motors by signaling with a whistle and your arms.’ There was no radio or anything like that. They engaged the motors so that the rope pulled slowly. When we were halfway across, the Warrant Officer, who had kept his head, said to me, ‘There is the end of the anchor cable. What shall I do?’ I could see what he meant. I said, ‘Let it go.’ And that was it, because the raft swung round and we came in perfectly,” he recalled.

Lieutenant Tom Flanagan of the 4th King’s Own Scottish Borderers, part of the 52nd Lowland Division, crossed the Rhine that night over “Sussex Bridge.” He recalled, “Our trucks were driven without lights except for the glow-light which shone on the white painted rear axle to enable following trucks to keep in touch in convoy. The narrowness of the Bailey bridge was made plain for the drivers by small lamps fixed to the sides of the girders placed every few yards along the way.

“As we drove up the ramp and onto the bridge I could hardly make out the swift flowing black depths of the river below nor could I hear anything but the noise from the engine of my Bedford Troop Carrier on which I rested my right arm, it being an overhead drive vehicle, as it ground its way along in low gear. Seated in the back, my HQ section, silent now as we slowly made our way, rocking up and down as the pontoons holding the structure moved with the weight of the lorry, into the cleared area of the west bank of the Rhine. Our packs strapped to our backs thrust us into an uncomfortable position in our seats and our steel helmets created an unaccustomed weight on our heads.”

Crossing the Rhine, Corporal Dai Evans of the Royal Welsh Fusiliers recalled, “Each of us was given a number of rubberized linen bags, shaped rather like long sausages with tapes fastened to their ends. These were lifebelts. Inflated by mouth, then tied around our bodies, they were supposed to give us a chance if we were dumped into the river. There were no instructions as to how to wear them but someone had worked out that if tied around the waist they would very likely turn us over in the water due to the weight of our equipment. It was decided it would be better to fasten them under the armpits, tying the tapes to our epaulettes to prevent them slipping down. We were given enough for each of our men to wear and instructed to tell them that if by any chance they were pitched into the river they were not to struggle but to get rid of all the equipment they could, letting the lifebelt support them. As the Rhine was a very fast-flowing river they were on no account to fight it but to let it carry them downstream while they swam towards the bank. Rescue teams with boats were stationed further down to pick up anyone in the water.”

“We Have Won the Battle of the Rhine”

So the Allied armies crossed the Rhine. The 11th Hussars led the famed 7th “Desert Rats” Armored Division across the Rhine on March 27. Colonel W. Wainmann, commanding the “Cherry Pickers,” threw away the regiment’s map-sheets as an indication that the 11th Hussars would never retrace their steps.

The 1st Royal Tank Regiment captured Heiden against light opposition, taking 18 guns and their crews, 10 trucks, and 60 prisoners on the 26th. Next day they had a harder time, losing a tank. As the rest of the vehicles tried to cross a stream by a flimsy wooden bridge, the bridge collapsed under the weight. Staff Sergeant Major Leonard Dauncey earned a Military Medal by organizing a party of men to build a ford or causeway. For three hours, under mortar and sniper fire that wounded three men, Dauncey and his crew finally succeeded and C Squadron got across the stream, amid rain.

The 11th Armored Division drove across the Rhine in heavy rain and entered the small town of Velen, where the local hotel served the advancing 8th Rifle Brigade and 3rd Royal Tank Regiment fresh bacon and eggs. Trooper Ernie Hamilton of the 15/19th Hussars collected nylon ropes used by the glider troopers, which were ideal for towing out tanks that got bogged down.

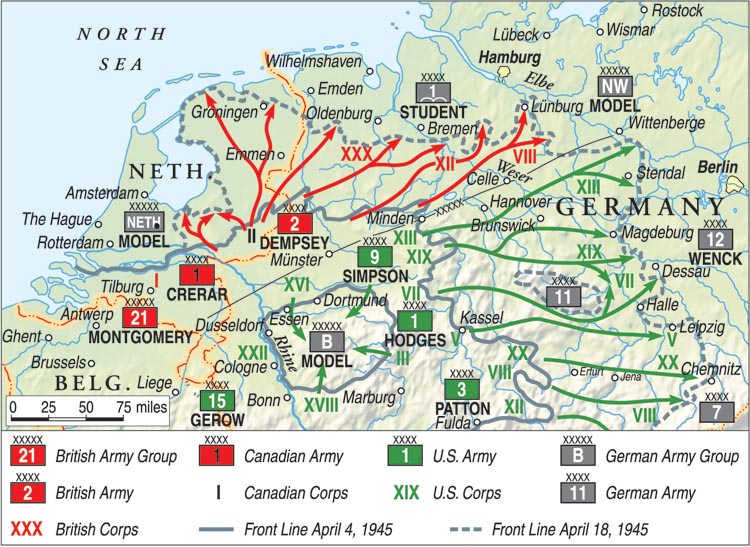

“We have won the Battle of the Rhine,” Montgomery told his Army commanders in a new directive on March 28. The Allied plan called for the 21st Army Group’s two armies, 1st Canadian and 2nd British, to advance at a high rate of speed to clear the North German Plain, seize the North Sea ports of Bremen, Emden, and Hamburg, and cut off the German defenders in the Netherlands. The U.S. 9th Army would be taken from Monty’s forces and used to help surround the industrialized Ruhr district.

Most importantly, the Allied plan did not call for the Anglo-American armies to take Berlin. General of the Army Dwight D. Eisenhower, Supreme Allied Commander, in one of his most controversial decisions, had ceded that to the advancing Soviet Red Army. Historians would endlessly debate the wisdom of that order.

Regardless of the decision’s wisdom, 21st Army Group still had to drive across northern Germany, and the Nazis would have something to say about that.

An Army of Boys and Old Men

The problem for the Germans was simply that there was not much left. Six years of World War II had drained the German Army’s strength. All the Germans had to throw against Monty’s advancing troops were training establishments, battered parachute regiments, and the Volkssturm, consisting of old men and Hitler Youth armed with one-shot Panzerfaust rocket launchers. A senior German officer, seeing the youngsters tramping along with their Panzerfausts, asked, “What will they do after they fire them? Use the launchers as clubs?”

Even so, the Panzerfaust was a superb anti-tank weapon, and the Hitler Youth made up in determination and loyalty what they lacked in tactical skill. The Germans were fighting for their homes now, and the advancing British and Canadian troops could not count on a friendly reception when they entered towns and cities.

The Canadian 1st Army could count on a friendlier reception, as it was tasked with liberating the Netherlands. Ironically, it would face some of the fiercest resistance of the final campaign.

The Canadians were ordered to drive north between the Rhine and the Dutch-German border to cut off the considerable Nazi defenses in the Netherlands. The Allied high command feared that the Germans might open the dikes in Holland to the sea and flood vast sections of the country, which was also suffering through the “Hunger Winter” of short rations and desperation.

A Three Days’ Fight For Emmerich

The first task was to clear the city of Emmerich to enable the Canadians to open a maintenance route over the Rhine. The 3rd Canadian Division’s 7th Brigade was assigned to take the city. It faced elements of the 6th Parachute and 346th Infantry Divisions. The fighting was vicious, and the city was heavily bombed and shelled. Backed by British Crocodile flamethrowing tanks, the Canadians found tough going.

“Enemy defenses consisted mainly of fortified houses and tanks and as each house and building had to be searched progress was slow,” the 7th Brigade’s war diary reported. “Our tanks in support found it almost impossible to maneuver due to well-sited road blocks and rubble.”

In three days of fighting, the Canadians took Emmerich, suffering 173 casualties, including 44 killed. The 8th Brigade, coming up behind, then took the Hoch Elten feature, a hilltop that overlooked Emmerich. That enabled the Royal Canadian Engineers to start throwing a Class 40 Bailey bridge across the Rhine at noon on March 31. At 8 pm the following night, the 1,373-foot Melville Bridge, named for a former chief engineer of 1st Canadian Army, was open for business. The Canadians also built the longest Bailey bridge in the entire European campaign, the 1,814-foot Blackfriars Bridge.

The force behind the Blackfriars Bridge was the 30th Canadian Engineers Field Company under Lieutenant William Fernley Brundrit. When construction began on March 26, Brundrit “worked unceasingly without regard for shelling, eating and sleeping; aiding in construction and in arranging for the large quantities of stores and equipment to arrive at the job, at the right time and place. When the bridge was completed … he fell asleep in his vehicle, completely exhausted.” His feat earned him a Military Cross.

With the bridges in business, the 1st Canadian Army took back control of 2nd Canadian Corps, and for the first time both of Canada’s corps were fighting side by side, with 1st Corps brought up from Italy in Operation Goldflake.

Backed by two more bridges, the 2nd Canadian Corps thundered across the Rhine at Emmerich with the 4th Canadian Armored Division and 1st Polish Armored Division in the lead. The first objective was the Twenthe Canal, held by the German 6th Parachute Division and some additional units.

The 4th Infantry Brigade hit the defense line in a night attack on April 2-3, crossing the river in storm boats, taking the Germans by surprise. Canadian troops captured German engineers who had been busy preparing positions for infantry who arrived too late to oppose the canal crossing. The Germans counterattacked, but 4th Brigade fended them off with light losses. The 4th Brigade’s war diary commented, “The enemy tactics appear almost juvenile at times—he is doing everything the book says as usual, but his training here shows that the caliber of troops opposing us is not what it used to be. Each enemy attack suffered very heavy casualties and usually a number of POWs were taken—grubby, dirty, slender youths, boys, and old men.”

Taking Zutphen

The Canadian advance up the Ijssel River continued, with the 3rd Canadian and 1st Canadian Divisions leading the way. The objectives were the towns of Zutphen and Deventer and their bridges. The 3rd Division closed in on Zutphen, defended by 361st Infantry Division with a parachute training battalion under command. The German troops included numerous teenagers, brought up in the Hitler Youth, who fought hard. The Highland Light Infantry of Canada built a bridge with 4.2-inch mortar boxes reinforced with timber and ballast, and it proved strong enough to carry the supporting tanks of the Sherbrooke Fusiliers Regiment across the Ijssel.

Zutphen was liberated by the North Shore Regiment and Le Regiment Chaudiere, which found, “For the first time there was evidence that the enemy’s attitude was gradually changing and although he fought well at times, the old tenacity was lacking,” according to 8th Brigade’s “Lessons Learned” report.

The 7th Brigade attacked Deventer from the east, and after a hard struggle entered the Dutch city. Once the Germans were down to their last defense line—an antitank ditch—they began to crumble. The Canadian advance cleared Deventer speedily with help from the Dutch Underground.

Operation Cannonshot

Operation Cannonshot was launched by the 1st Canadian Division halfway between Zutphen and Deventer to clear a route from Arnhem to Zutphen. Two veteran Canadian regiments, Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry and the Seaforth Highlanders of Canada, crossed the river in Buffaloes, surprising the German defenders. The Seaforths found no opposition while the Princess Pats secured their ground after knocking out a French tank the Germans were using.

Five companies of engineers threw bridges across the Ijssel. On April 12, the 1st Canadian Brigade passed through the bridgehead and headed west toward Apeldoorn. The 48th Highlanders of Canada suffered a great loss. Their commanding officer, Lt. Col. D.A. McKenzie, was killed by a shell. At 6 am on the 13th, the 1st Division reverted to 1st Canadian Corps and headed for Apeldoorn and Arnhem.

Meanwhile, the 2nd Canadian Corps continued its advance from Twente, racing up the Dutch-German border. On April 6, the 6th Infantry Brigade reached the Schipbeek Canal about eight miles east of Deventer. The Germans blew the only bridge in the area, but the Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders of Canada crossed the damaged structure anyway and set up a bridgehead on the opposite bank.

With the advance moving forward briskly, the Allies threw in paratroops behind German lines to cause more chaos among the defenders. The 2nd and 3rd French Regiments de Chasseurs Parachutistes’ 700 French SAS men were to harass the Germans and provide guides and information for the advancing Canadian 1st Army. Operation Amherst scattered French SAS teams behind German lines, and they captured 200 and killed 150 Germans, preventing the destruction of numerous bridges.

2,400 POWs in Groningen

The 2nd Corps now moved on Groningen, near the North Sea. The fast-moving Canadians took a canal bridge intact west of Beilen on April 12 and took the town by surprise from the rear after two hours of fighting, seized Assen on April 13, and penetrated Groningen’s southwestern suburbs on the same day. Everywhere Dutch civilians danced in the streets and cheered their liberators.

Groningen was defended by miscellaneous German troops, including Dutch renegade SS men, who fought with the courage of men who knew they would face treason trials if captured. The Canadians fought hand-to-hand against the Germans, clearing out every room of four-story apartments. German troops deployed machine guns in basements, and Dutch SS men in civilian clothes sniped at the Canadian troops.

On the evening of April 14, the Essex Scottish found a bridge intact across a large canal in the southern part of the city, and the 5th Brigade moved across rapidly. “In spite of the severe fighting … great crowds of civilians thronged the streets—apparently more excited than frightened by the sound of nearby rifle and machine-gun fire,” reported the 2nd Division’s war diary. Because of the civilians, 2nd Division held back its artillery and air strikes, accepting the possibility of delay and additional casualties.

The German commander and his staff surrendered Groningen on the 16th, but stubborn elements of the garrison held out a little longer. At the city’s eastern edge, the Germans had raised a lift-bridge over the Van Starkenborgh Canal, and the mechanism to lower it was on the wrong side. Dutch civilians, one of whom was the bridge tender, offered to help. Accompanied by the Cameron Highlanders of Canada, the Dutch crossed the canal under fire on a ladder. The bridge tender was wounded, but he lowered the bridge. German resistance then collapsed.

The Canadians took 209 casualties at Groningen but captured approximately 2,400 POWs. In the course of their advance from the Rhine to the North Sea, the 3rd Canadian Division had fought forward 115 miles in 26 days, built 36 bridges, and captured 4,500 prisoners.

Setting Friesoythe Ablaze

Meanwhile, the 2nd Corps’ two armored divisions also rumbled ahead, northeastward to the Ems River. The 4th Armored Brigade made an assault crossing at Meppen, taking one casualty and quickly overrunning the town. Among the POWs captured were 17-year-olds with six to eight weeks of military experience.

After the 4th Armored crossed the Ems, German defenses began to weaken. A divisional staff officer said, “The enemy was, perhaps, never entirely out of control, but he appeared to be seriously disorganized. For the first time we began to meet the passive opposition of demolitions and mines rather more often than the active opposition of ground troops.” The Canadians were slowed more by boggy terrain than German defenses.

But at the town of Sogel, the Germans fought back with several counterattacks. The Lake Superior Regiment and Lincoln and Welland Regiment chased off the Germans but came under sniper fire from civilians. The Canadians retaliated by bulldozing a number of houses in the center of town.

Another town faced bulldozing when the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders of Canada attacked and took Friesoythe. Their commander, Lt. Col. F.E. Wigle, was killed by a sniper. Rumors swirled that the sniper was in civilian clothes, and Friesoythe was ordered burned—whether by division or brigade headquarters is not known. Canadian Wasp flamethrowers trundled up and down the streets of the town, wrecking its center. There was no investigation by Canadian authorities.

Operation Destroyer

Now the Canadians headed for their next objective, the city of Oldenburg, across the Kusten Canal. On April 16, the 10th Brigade attacked by boat across the canal. German defenders came from the 2nd Parachute Corps and a marine regiment. Covered by the New Brunswick Rangers’ machine guns, the Canadians had their objectives in hand by dawn. The Germans counterattacked with infantry and a single self-propelled gun, which was beaten back. Engineers threw Algonquin Bridge over the canal under appalling conditions, and the British Columbia Regiment crossed immediately.

While the 2nd Corps fanned out across northwest Germany, the 1st Corps prepared to attack into the Netherlands. The first task, to clear out Arnhem and Oosterbeek, was assigned to Maj. Gen. S.B. Rawlins’ 49th West Riding Division and Maj. Gen. Bert Hoffmeister’s 5th Canadian Armored Division. Operation Destroyer kicked off on April 2 with the 49th crossing the Rhine west of Arnhem. Resistance was slight despite German propaganda communiqués referring to “fierce fighting” in the Arnhem sector. The first outfit across the Neder Rijn was the same battalion that had crossed the Seine and the Dutch frontier first, the Hallamshire Battalion of the York and Lancaster Regiment.

Operation Quick Anger: Taking Arnhem

By April 5, “The Island,” the section of land between Nijmegen and Arnhem, scene of fierce fighting during Operation Market-Garden in the fall, was in British hands, and Operation Quick Anger, the attack on Arnhem, followed next. The 2nd Gloucesters manhandled their assault boats over the dike in front of the river to attack Scheisprong Fort, suffering 32 casualties, but took 60 German prisoners.

The 2nd Essex followed and found the remains of the British defense of the Oosterbeek perimeter as they advanced. Lieutenant A.A. Vince of the 2nd Essex recalled, “We saw the evidence of the tragedy of September 1944, the broken guns and equipment, the little shallow slits the Airborne had dug in a few seconds and from which they had fought for days. We saw the little white crosses in corners of Dutch gardens, often with an inscription such as ’31 Unknown British Soldiers.’ On top of the cross would be a weather-stained Red Beret placed there by the Germans as a tribute to the cream of fighting men.”

The first battalion into Arnhem was the 2nd South Wales Borderers, which found the city badly wrecked from the 1944 and 1945 battles.

Major Godfrey Hartland of the 1st/4th King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry recalled, “At first light with the aid of some Canadian tanks we attacked some German positions in the grounds of Sonsbeek Hospital. It was to be our last company attack in Northwest Europe. The company was digging in, having taken the objective, when the customary German counterattack by shell and mortar fire arrived, landing on a section of the right hand platoon. Three were killed and two were wounded. Sad to lose those three splendid young soldiers, Geordie Alcock, M. Durham, and F. Lees, who had fought so many battles with the company only to lose their lives so late in the war.”

The German defenders were mostly Dutch renegades of the SS Landstorm Nederland, who fought with determination. The Germans had evacuated the city’s population.

The 56th Brigade attacked across the Ijssel River in Buffaloes with heavy air and artillery support. Canadian tanks of the Ontario Regiment and British infantry fought through the ruins, losing 62 dead and 134 wounded. More than 1,600 Germans were taken prisoner and twice that number put out of action by the time Arnhem was taken on April 16.

Defenses “At Any Price”

Next up was the capture of Apeldoorn to cut off western Holland from Germany. The 1st Canadian Infantry Division, under Maj. Gen. Harry Foster, and the 5th Canadian Armored Division were given the job. The Germans delayed the Canadian advance with mines—sometimes naval shells planted in the roads—and snipers.

German defense measures were increasingly desperate. On April 12, SS Reichsführer Heinrich Himmler issued a decree that read, “Towns, which are usually important communications centers, must be defended at any price. The battle commanders appointed for each town are personally held responsible for compliance with this order. Neglect of this duty on the part of the battle commander, or the attempt on the part of any civil servant to induce such neglect, is punishable by death.”

The Canadians moved on Apeldoorn but were reluctant to hurl airpower and artillery into a city filled with refugees and 72,600 inhabitants. The Canadians had 5th Armored swing past Apeldoorn on the left, cutting it off, while the 1st Canadian Division attacked it from the east.

German resistance in the city disintegrated on the night of April 16-17. By noon on the 17th, the 1st Canadian Brigade had taken over the old German headquarters as their own, to wild rejoicing by the citizens. “National colors of the Netherlands were flying in the brilliant sunlight from almost every house and shop,” recorded the 1st Division’s summary of operations. The 1st Division suffered 506 casualties in liberating Apeldoorn, taking 40 German officers and 2,515 enlisted men prisoner.

Drive Into Western Holland

The Canadian 1st Corps now aimed to clear western Holland with Operation Cleanser. The 5th Armored Division moved through “densely wooded sandhills, making observation and mutual support extremely difficult and often impossible. Movement off roads around roadblocks was accomplished only through the sheer weight of the tanks forcing their way through the trees.” But the speed of the Canadian advance caught the Germans off balance. At Deelen, the headquarters staff of the 858th Grenadier Regiment was overrun. The commander conceded that he had been “taken completely by surprise when attacked by tanks and found his dispositions all wrong.”

On April 15, Lord Strathcona’s Horse headed for Otterloo, attacking by night through deep water-filled ditches and low marshy ground. The Germans continued to withdraw, leaving behind demolitions and booby traps. On the night of April 16-17, they counterattacked against the Irish Regiment of Canada and Hoffmeister’s own headquarters with artillery and mortars. All headquarters personnel were soon involved in the battle with Canadian artillery firing over open sites, demolishing a church tower in their efforts to shorten the range. At dawn the headquarters tanks and Irish counterattacked, joined by Wasp flamethrowers. The Germans suffered 300 casualties, with between 75 and 100 killed. The Irish lost 22 men and the 17th Field Regiment 25 and three guns knocked out.

In 10 Days it Will be Death

By the morning of the 17th, the 5th Armored was wrapping up Operation Cleanser, driving all the way to the Ijsselmeer. The division captured 34 German officers and 1,755 other ranks, many of them Dutch “volunteers” who served in the Wehrmacht to avoid conscription as slave laborers. Now the Canadians could assault the Grebbe Line and drive into western Holland.

Standing in the way was a force more powerful than the Wehrmacht’s disintegrating legions, the German Reichskommissar for Holland, the obnoxious and cynical Austrian Artur Seyss-Inquart, who warned that any Allied attack into western Holland would be met by his opening the dikes and the horrendous flooding of the nation’s lands below sea level.

The Netherlands was in terrible condition by this time—the winter of 1944-1945 is forever known in that nation as the “Hunger Winter” because of desperate food shortages. Dutch residents were barely surviving on as little as 500 calories a day. Heating coal and coke were also in short supply, forcing starving and exhausted Dutchmen to chop down forests and cut up furniture to stay warm.

All across the Netherlands, citizens suffered under the German heel. Parents sent their children out to steal; women sold themselves to German soldiers for a few cans of soup; rich and poor traveled on rickety bicycles or bleeding feet hundreds of miles to barter watches or bed linens with farmers for potatoes or eggs. The “hunger trippers” often had their food confiscated on the way home by equally famished German troops. By April, the average Dutch city dweller’s ration was down to 230 calories per day. Ten-year-old Henry A. van der Zee recalled, “My days were spent, for the most part, in queuing for whatever the ration cards promised us. It was so cold outside that I still remember the tears of pain and misery turning to icicles on my cheeks.”

“It is already famine,” Dutch food officials wired London on April 24. “In 10 days it will be death.”

Seyss-Inquart’s Shrewd Deal With the Allies

Seyss-Inquart showed his power over nature by opening a dike near Den Helder to inundate the country’s newest polder, a 75-square-mile area. He then warned the Canadians that if they attacked over the Grebbe Line he would blow another dike between Rotterdam and Gouda, causing massive flooding all the way north to Amsterdam—effectively destroying western Holland. Furthermore, he had orders to leave Holland a “field of ruins.”

Instead, in January Seyss-Inquart summoned a Dutch government official who had stayed behind under orders, Dr. H.M. Max Hirschfield, to discuss the growing crisis in western Holland and possible solutions. Hirschfeld suggested negotiations. The cynical Seyss-Inquart knew that Germany was doomed but was reluctant to risk his own neck by opening negotiations. He suggested a “basis of agreement” between the German forces and the Allies so that a status quo could be maintained.

The Dutch government-in-exile, now back home in the liberated areas of the Netherlands, opened secret talks with Seyss-Inquart. The Dutch proposed that the Canadians stop their advance on the Grebbe Line. In return, the Gestapo would cease executions, decently house political prisoners, and any culprits who carried out attacks on German installations would not receive the death sentence. There would be no further inundations. The Germans would also help facilitate the opening of Rotterdam’s port to barges bearing food and coal from the south.

Seyss-Inquart emphasized that there would be no official surrender, and the occupation would be maintained. Outwardly, the Canadians would merely stop on the Grebbe Line and not attack any farther.

When this plan reached 1st Canadian Army, the Canadians saw advantages to it—a massive assault across the Grebbe Line would take Holland, but at a huge price in both Canadian and Dutch lives. With the war nearly over, it was time to save lives on both sides of the front line.

The higher Allied leadership also agreed, with Winston Churchill fearing operations “would be marked by fighting and inundations and the destruction of the life of Western Holland,” and General Eisenhower writing that “for sheer humanitarian reasons something must be done at once.” Ike agreed to Seyss-Inquart’s proposal, and the 1st Canadian Army ground to a halt on the Grebbe River.

Corporal Chapman’s One-Man Stand

Meanwhile, the British 2nd Army began streaking across the Rhine, heading for the North German ports. The Germans fought for every hamlet and town, usually with small groups of infantry—often Hitler Youth—armed with Panzerfausts, sometimes supported by Tiger tanks.

Despite this, the 2nd Army made a rapid advance toward Bremen. The 12th Corps reached the Ems and turned south to cross the Dortmund-Ems Canal, where the 7th Armored Division took up the fight. The division crossed the Ems on April 3 and captured the town of Ibbenburen after a stiff fight against snipers, many of them officer cadets and noncommissioned officers from the local tactical training school.

Platoon commander Robert Davies of the 2nd Devonshires recalled, “The leading platoon was carried forward on tanks. When we met with resistance we left the vehicles behind and went on with or without tanks, depending on the countryside. We spent a lot of time sitting on the back of the tanks going in, and the only snag was that you could not hear anyone firing at you for the noise of the engines and the tracks. One man was kneeling between my knees, speaking to me, I had my back to the turret, and the next moment he fell dead. When the company went in we followed our own creeping barrage, and when we got to the heights we had to winkle out the [German officer] cadets who were well dug-in. They had been badly shelled but they were really tough. Afterwards, when we were collecting the wounded, I found one boy under a bush, who spoke perfect English, and asked me if the stretcher bearers had gone. I said, ‘Yes,’ and he said, ‘In that case I’ll die.’ It was just as well that he did. He was very good-looking but had no arms or legs.”

The Ibbenburen battle was wild. Corporal Edward Chapman of the 3rd Monmouths staged a one-man stand against repeated German counterattacks, driving them back with his Bren gun. Once the attacks were temporarily driven off, Chapman went out alone to recover his wounded company commander, who was, unfortunately, dead. Chapman himself was wounded and refused to be evacuated.

“Throughout the action Corporal Chapman displayed outstanding gallantry and superb courage. Single-handed he repulsed the attacks of well-led, determined troops and gave his battalion time to reorganize on a vital piece of ground overlooking the only bridge across the canal. His magnificent bravery played a very large part in the capture of this vital ridge and in the successful development of subsequent operations,” read his Victoria Cross citation. Chapman survived the ordeal to receive his VC from King George VI in July 1945, and he died in 2002.

“Bash On Regardless”

Attached to the 7th Armored was the 1st Commando Brigade, which attacked and captured Osnabruck on April 4. Commando Bill Sadler recalled, “The brigade entered Osnabruck on the early hours of Sunday morning, suffering some casualties from Spandau fire which produced the usual Commando reaction: ‘Bash on regardless.’ We sprinted across the open ground in groups and the Spandau was knocked out by a well-placed PIAT bomb. We had completed the capture of the town by 10 am, mopping up a few pockets of resistance and taking about 400 prisoners, including some Hungarians. The local Gestapo chief was shot dead in his office by our Field Security Officer, Major Viscount de Jonghe—then we went on to the Weser.”

There were humorous moments in the great advance for the “Desert Rats.” One patrol captured a German staff car, finding inside four high-ranking German officers, complete with maps and documents and a case of cognac. Also, C Squadron of the 11th Hussars captured some Germans, one of which turned out to be 60 years old, wearing carpet slippers, and carrying a walking stick, without which he would have fallen down.

The 8th Corps reached the Weser on April 5. The 7th Armored found the bridges over the river destroyed and had to turn west for Wildeshausen and Delmenhorst to cut off the retreat of the 1st Parachute Army.

The 11th Armored Division fought hard battles in the Teutoburger Wald against the Clausewitz Panzer Division, made up of training units. The British tanks entered the small town of Tecklenburg to find no white flags flying, unlike in other conquered communities. The Germans fought back with Clausewitz regulars and Volkssturm against the British, who battled down narrow, twisted streets. By nightfall the town was conquered, charred, and burning.

Next up for the 11th Armored was the Rive Weser, where the Germans decided to make a stand on the 5th, blowing bridges in front of the advancing British troops. The 11th Armored faced the 12th SS Panzer Division. The 1st Herefords and 8th Rifle Brigade were sent over the river in assault boats under heavy and light antiaircraft fire. The two battalions hacked out a bridgehead, and Royal Engineers began throwing a Bailey bridge over the Weser.

Death Throes of the Luftwaffe

At this point, the Luftwaffe finally intervened, with Junkers Ju-87 Stuka dive bombers and Focke-Wulf FW-190 and Messerschmitt Me-109 fighters all bearing down on the British. A British soldier recalled, “Our own Brens and Brownings chattered constantly against the marauders but they were quite futile, the tracers visibly bouncing off the armored bellies of the Boche planes as they swooped low over the rooftops.”

Another Briton grabbed a Bren gun and fired a stream of bullets into the nose of a diving Heinkel bomber. “I watched the tracer drift almost lazily into its center front. The aircraft veered sharply to port, lost height, drifted over some trees and disappeared.”

Royal Air Force Hawker Tempest fighter bombers arrived at midday on the 6th to fend off the Luftwaffe, but the 12th SS and 100th Pioneer Brigade put up a firm defense. The Herefords set up their headquarters in a farmhouse that had the advantage of having vast quantities of preserves, bottled fruit, and vegetables, plus chianti and hams. The Germans attacked in waves, and the British crushed the attack with barrages of artillery. “That’ll teach the bloody Boche,” said a British officer.

The Luftwaffe would not yield. Its bombers destroyed a Bailey bridge. With the British pinned down by heavy fire and no way to get tanks over, they were forced to withdraw. Luckily, the tough 6th Airborne Division had built a bridge at nearby Petershagen, and the 11th Armored used the airborne division’s bridge to maintain the pace of the offensive.

“No One Wanted to Take Any Risks Anymore”

Next was the Aller River, and the 11th Armored clanked toward it, battling determined Hitler Youth snipers. At Husum, the 4th King’s Shropshire Light Infantry lost 13 dead and 30 wounded to Hitler Youth, but in turn killed 80 and captured 120. The Inns of Court Regiment moved in to help the 11th Armored.

Peter Reeve of the Inns of Court Regiment recalled, “They were in the throes of a bloody battle with an SS unit who had looted the village and shot several KSLI prisoners in cold blood in the back of the head. We were met by a hail of fire from Schmeissers. An SS officer crouched with his machine gun cradled as we loosed off bursts from the Browning. He went on firing till he was cut almost in half. Late in the evening all opposition ceased—a grisly pile of burned bodies being the only memento.”

The 11th Armored rolled on, liberating POW camps and seizing German ammunition dumps. The division even captured a V-2 rocket-launching site. Bill Close of the 3rd Royal Tank Regiment wrote, “No one wanted to take any risks anymore. The men in lead tanks knew they would be the first to get it if they bumped into a last-ditch battle-group. People were reluctant to drive around corners. I gave orders that no chances were to be taken with bazooka merchants.”

The End of the Strategic Bombing Campaign

The British advanced through rich Prussian corn land, with well-stocked farms, a peaceful part of the Reich that had not been touched by war. Still the SS and Hitler Youth fought on. At Steimbke, the British had to launch a setpiece attack into the village. Noel Bell recalled, “The SS fought fanatically and every house had to be cleared individually. Our stretcher-bearers were fired on, which spurred us on even more. No quarter was given or asked and very few SS prisoners lived to tell the tale.”

When the British reached the Aller, they again found all bridges blown, but the 1st Commando Brigade forced a river crossing at Essel. The 11th Armored borrowed another 6th Airborne bridge and drove through heath and pine to capture a Luftwaffe airfield complete with 12 aircraft.

On the night of April 11, the 4th King’s Shropshire Light Infantry crossed the River Aller to widen the commando bridgehead, and the British were heading for the Elbe.

Germany was now a picture of wrecked towns and villages. On April 16, the Allies called off the strategic bombing campaign against Germany because most targets had been captured and those left were about to be—further bombing would only provide defenders with more rubble.

“No Fraternization”

While SS men, paratroopers, and Hitler Youth fought on, the rest of the German Army’s morale had collapsed. The rate of desertion was so high that Field Marshal Albert Kesselring, commanding the German forces in the West, used his best men to round up the faint of heart who flooded to the rear whenever a battle started.

“The enormously costly battle of the last half-year and constant retreat and defeat had reduced officers and men to a dangerous state of exhaustion,” he wrote. “Many officers were nervous wrecks, others affected in health, others simply incompetent, while there was a dangerous shortage of junior officers. In the ranks strengths were unsatisfactory, replacements arriving at the front insufficiently trained, with no combat experience, and, anyways, too late. They were accordingly no asset in action. Only where an intelligent commander had a full complement of experienced subalterns and a fair nucleus of elder men did units hold together.”

With much of northern Germany now occupied by advancing British and Canadian forces, the “no fraternization” rule went into effect, barring Allied troops from even giving candy to German urchins. But the Tommies broke it anyway. From meeting children it was a short step to meeting their older sisters or widowed and lonely mothers.

A Hard Day’s Fighting in Winsen

Meanwhile, the advance continued. The 46th Royal Marine Commando attacked a wood near Hademstorf, and the Commandos were astonished to find their opponents to be a German marine division. Unlike the British marines, the German marines were simply sailors released from immobile warships. The British took 60 prisoners.

The 3rd Royal Tank Regiment ran into Tiger tanks trying to contain the British bridgehead over the Aller River. John Langdon, in a Comet tank, saw the Germans coming, and recalled, “About 300 yards away I saw its 88mm gun slowly traversing on us. We fired. Head-on as it was to us we could not hope to knock the tank out. We were outgunned and if I wanted to save my tank and crew there was only one thing to be done.” The Comet was reversed into cover, knocking over 40-foot fir trees. But the next day, in a rematch, the British “brewed up” one Tiger and forced the other to withdraw.

On Friday, April 13, the Germans counterattacked the bridgehead in force, and 300 Germans died on the field. The following day, the Cheshires attacked Winsen, defended by the staff and students of a nearby antitank officers’ training unit equipped with 88mm guns, 75mm self-propelled guns, and piles of Panzerfausts. The Germans bombarded the British with Nebelwerfers, multibarreled rocket mortars, and the offensive was slow going. By 6 pm, the woods were cleared for a cost of three officers and 11 other ranks killed, two officers and 29 other ranks wounded. It was the hardest day’s fighting for the battalion since it landed in Europe.

The Surrender of Belsen Concentration Camp

On the same day, a German staff car with a large white flag carrying two German medical corps officers arrived at the Cheshires’ headquarters. They claimed to have been sent by the commandant of Belsen Concentration Camp with orders to surrender the facility to the nearest British troops.

The 11th Armored Division sent in a detachment, and Major Derrick Sington of the Intelligence Corps became the first Allied soldier to enter the notorious concentration camp. Passing through the main gates, barrack blocks, and huts, he found an inner compound.

“It reminded me of the entrance to a zoo. We came into a smell of ordure—like the smell of a monkey house. A sad, blue smoke floated like ground mist between the low buildings. I had tried to imagine the interior of a concentration camp, but I had not imagined it like this. Nor had I imagined the strange, simian throng, who crowded the barbed wire fences surrounding their compounds, with their shaven heads and their obscene striped penitentiary suits,” he wrote.

“We had been welcomed before but the half-credulous cheers of these almost lost men, of these clowns in terrible motley, who had once been Polish officers, land workers in the Ukraine, Budapest doctors and students in France, impelled a stronger emotion and I had to fight back my tears.”

Built to hold 8,000 prisoners, Belsen now had more than 56,000 crammed into 80 single-story huts, where they lay on wooden shelves, dead and dying huddled together.

10,000 Bodies

The 11th Armored dashed into the camp, but it was 24 hours before the tankers could take full control of it. Once they did, they found more horror. There were some 10,000 unburied bodies lying about the camp.

The appalling situation soon became the responsibility of the 2nd Army’s Chief Medical Officer, Brigadier Hugh Glyn Hughes, who had worried days before about the possibility of infectious diseases at the camps the Army would be liberating.

“No photograph, no description, could bring home the horrors I saw,” Glyn Hughes said later. “The huts overflowed with inmates in every state of emaciation and disease. They were suffering from starvation, gastroenteritis, typhus, typhoid, tuberculosis. There were dead everywhere, some in the same bunks as the living. Lying in the compounds, in uncovered mass graves, in trenches, in the gutters, by the side of the barbed wire surrounding the camp and by the huts, were some 10,000 more. In my 30 years as a doctor, I had never seen anything like it.”

Hughes moved in field hospitals, but it was not enough. Under British guard, both the SS camp warders and civilians from neighboring communities came in to bury the dead.

The camp’s commandant, the appalling Joseph Kramer, was taken into custody. A furious British soldier told him, “When they hang you, I hope you die slowly.” He was indeed hanged after his war crimes trial.

Another Briton provided a shocking account of the camp for the world. BBC reporter Richard Dimbleby sobbed into his microphone on April 19th: “I picked my way over corpse after corpse in the gloom, until I heard one voice raised above the gentle undulating moaning. I found a girl, she was a living skeleton, impossible to gauge her age for she had practically no hair left, and her face was only a yellow parchment sheet with two holes in it for eyes. She was stretching out her stick of an arm and gasping something, it was ‘English, English, medicine, medicine,’ and she was trying to cry but didn’t have enough strength. And beyond her down the passage and in the hut there were the convulsive movements of dying people too weak to raise themselves from the floor.”

Dimbleby watched a woman, “distraught to the point of madness,” fling herself at a British soldier, begging for milk for her baby.

“She laid the mite on the ground and threw herself at the sentry’s feet and kissed his boots. And when, in his distress he asked her to get up, she put the baby in his arms and ran off crying that she would find milk for it because there was no milk left in her breast. And when the soldier unwrapped the bundle of rags to look at the child, he found that it had been dead for days … this day at Belsen was the most horrible of my life.”

Operation Bremen

The British were in no mood to trifle with the Germans after this shocking discovery and moved briskly to take Hamburg and Bremen.

Bremen was up first. Operation Bremen began on April 13, with the 3rd Infantry Division attacking into the city’s suburbs. Opposing a British division that had landed on Sword Beach on D-Day were an SS training battalion, antiaircraft crews, Volkssturm senior citizens, Bremen police officers, and U-boat and R-boat crews taken from their immobile naval vessels.

The 1st South Lancasters led the 8th Brigade’s attack up a main road, and Bren carrier driver Joe Garner and his pals dismounted from their vehicles and rushed a house. “We managed to kill and wound some of the enemy and take the remainder prisoner. Meanwhile our antitank detachment had arrived and took a position about 20 yards away from the house. I carried out my usual looting recce—looking for Nazi memorabilia—nothing worth bothering with. Going into the cellar, however, we discovered the shivering house owners sheltering therein.”

The brigade drove up the straight road, past objective lines named Penny, Farthing, Dime, and Mark with mixed groups of infantry and Churchill flamethrowing tanks. German troops pinned down the 1st Suffolks until the tanks clattered up and set fire to the defenders’ houses.

For days the 3rd Division battled for the small houses of Bremen’s suburbs, taking casualties that included 2nd East Yorks’ second-in-command, Major C.K. “Banger” King, who had inspired his men on D-Day by reciting Henry V’s classic speech to them. But the Germans could not stop the British advance.

The division’s commander, Maj. Gen. “Bolo” Whistler, wrote in his diary, “We have captured five officers and 1,259 men on April 15th and another 1,800 between 15-19th. We have killed about 200-300 more. Not much shelling from the Boche for which I am truly thankful. Lovely weather! Had a close look at Bremen yesterday. It appears rather undamaged in spite of Bomber Harris and his efforts.”

The Last Victoria Cross in Europe

On April 21, Edward C. Charlton earned the last Victoria Cross won in Europe in World War II. His tank unit had just helped an infantry platoon seize the town of Wistedt, and the Germans put in a counterattack consisting of officer cadets supported by three self-propelled guns. Three of the four Irish Guards tanks were hit, and Charlton’s was disabled by a complete electrical failure before the attack began. Charlton was ordered to dismount the turret machine gun and support the infantry.

Charlton, on his own authority, took the machine gun and advanced in full view of the attacking Germans, firing the weapon from his hip as he did so and inflicting heavy German casualties. The lead German company was halted, and this allowed the rest of the Guards a respite in which to reorganize and retire. Charlton continued his bold attack, even when he was wounded in his left arm.

Charlton placed the machine gun on a fence, where he launched a further attack before his left arm was hit again by enemy fire, becoming shattered and useless. Charlton, now with just one usable arm, carried on his attack until a further wound and loss of blood resulted in the Guardsman collapsing. His courageous and selfless disregard for his own safety allowed the rest of the Irish Guards troop and infantry to escape. He later died of the wounds.

His Victoria Cross is on display at the Irish Guards Regimental Headquarters at Wellington Barracks in London. He is buried in Becklingen War Cemetery in Germany.

“Only Cowards Surrender”

Bremen fought hard. The defenders had advantages, including low-lying land that was partially flooded, which made it impregnable to a conventional tank and infantry assault. The British called in RAF Bomber Command to plaster the city’s considerable defenses, which ranged from heavy flak guns to Hitler Youth.

One of the defenders, Werner Ellebeck, recalled, “We had military training, although it didn’t always make sense to us. However, one thing we were drilled in very thoroughly was the use of the Panzerfaust—our task was to destroy tanks. We were provided with few other weapons. The order was ‘find them yourselves,’ which we were happy to do. We managed to get hold of a lot of weapons from abandoned camps and flak batteries, so that most of the company possessed Panzerfausts and the rest had a collection of carbines, hand grenades, and a few machine guns. Armed with these, we were filled with great confidence.”

But the civilian population lived in terror in air raid bunkers. “A terrible, claustrophobic squeeze would be an understatement to describe the masses of people herded together in here. These people are unwashed and ungroomed—there is no fresh water—and often the air is barely breathable. Fainting and nausea are common but anything vaguely approaching sanitary conditions is not even talked about anymore. Flu, throat infections, and the like are gaining the upper hand on a daily basis,” wrote Albrecht Mertz.

Outside, diehard Nazis handed out propaganda messages, which included such statements as “The German Volk is determined to fight to the last breath,” and “Only cowards surrender.” Any sign of a white flag would be punished by death.

The RAF hammered Bremen, joined by British artillery. By April 21, there was still no sign of surrender. “A handful of madmen are in charge,” wrote one disillusioned citizen. “Everything is covered in a chalky layer of grayish red … the road is strewn with tree branches and rubble.”

An Ultimatum For Bremen

Lieutenant General Sir Brian Horrocks, commanding 30th Corps, which was attacking Bremen, gave the city’s defenders an opportunity to surrender, hurling an ultimatum in 4,000 artillery shells at the Germans. Still no response. On April 24, Horrocks sent in the 52nd Lowland Division and the 3rd Infantry Division, which crossed the flooded areas on Buffaloes while the RAF and artillery pounded the defenders.

The bombing and shelling had the desired impact. The 2nd King’s Shropshire Light Infantry took 200 prisoners. The Norfolks reported, “The softening-up of Habenhausen had been complete, and those of the enemy who had not made off were only too glad to give up without a fight.… By 6 that evening it was all over, and a few locals, headed by the village policeman, were filling in bomb-craters under the supervision of the Pioneer Officer.”

The main battle would clearly be fought outside the city, and the 2nd Royal Ulster Rifles crossed the Weser under full moonlight in Buffaloes, facing heavy antitank and flak gun fire. Corporal D. Lambourn earned a Military Medal by charging a German position and taking it. The Royal Ulster Rifles bagged five officers and 128 other ranks in the assault, and their boss, Lt. Col. J. Drummond, earned a Distinguished Service Order for commanding it.

The 185th Brigade attacked at night as well, relying on Buffaloes to cross the Weser. Marcus Cunliffe recalled, “The noise of [the Buffalo] engines was drowned by the greater thunder of the artillery barrage. To the inhabitants of Bremen crouching in their shelters, it must have all sounded like the final intimation of doom. Crammed into the ‘holds’ of the Buffaloes the Warwicks could only see the sky overhead traversed at five minute intervals by the red trace of three Bofors shells over the objective as a guide to direction.”

Everything went well in the effort to take the causeway over the Weser, and by noon it was in British hands. By now, the German defenses were harsher in their verbiage than in battle—most defending Germans seemed to give up soon after being battered by British shells.

“The Hun Was Utterly Demoralized”

The drive into Bremen continued through the 26th. That day, Brigadier W. Kempster, commanding the 9th Brigade, found “the Hun was utterly demoralized, 2nd RUR just walked on to their objectives and by 9:30 am I reported to Division that we’d done our job—nearly 30 hours in advance of the estimate.”

Raymond Burt of the 22nd Dragoons wrote, “So this was how the city was falling—without fight, in rain, and betrayed by those who had brought it into its present squalor. For all their boasts and threats, the Nazi leaders had gone and the city was abandoned to a few thousand AA gunners and marines and the old men and women and children who waited our arrival in the air raid shelters. The advances into the suburbs were something of a formality. But they were carried out block by block, with care and precision—companies and supporting tanks leapfrogging through one another along the silent and mined streets. It looked formidable enough; the road blocks were defensible. Slit-trenches and antitank ditches had been dug across street intersections: enormous land-mines had been laid and wired ready for explosion by the roadsides. The windows of the ruined houses provided the ‘heroic twilight’ of the Nazis and the city of Bremen. But no shot was fired.

“Hitler’s war was running down—it had collapsed into a dreary mopping-up operation which went on because no one in authority had the desire to cry ‘Stop!’”

Taking the Elbe on the Run

With Bremen falling, the next objective was the Elbe River, and Monty prepared a set-piece crossing of it. But Eisenhower wanted the Elbe taken with great speed, to beat the Soviets into Schleswig-Holstein and Denmark, so he ordered Montgomery to take the Elbe on the run and assigned the U.S. 18th Airborne Corps to Monty’s right flank with orders to cross the Elbe at Bleckede.

The 505th Parachute Regiment, veterans of four drops, was assigned the task, going over by night on April 29 in collapsible wooden boats. Colonel William Ekman’s paratroopers fished the defending and sleepy Germans out of their foxholes with rifles, using flashlights to find them. By dawn, the paratroopers had secured the bridgehead, and engineers threw pontoon bridges across the Elbe to enable 18th Corps’ armor to move across under heavy shellfire. Major General Matthew Ridgway, the 18th Corps commander, inspired the troops by walking out onto the unfinished bridge under the shelling, earning a second Silver Star.

That day, the British also continued their offensive, with the 7th Armored Division heading into the ruined city of Hamburg. General L.O. Lyne, commanding the Desert Rats, sent Maj. Gen. Alwin Woltz, the German commander in Hamburg, a six-point letter demanding the city’s surrender. Negotiations went back and forth and at 7 pm on May 1, a large black Mercedes car with an even larger white flag arrived in the D Company area of the 9th Durham Light Infantry bearing two officers from Woltz’s staff, ready to surrender the city. They were followed by hordes of German troops and civilians, including the champion boxer Max Schmeling.

The Death of Adolf Hitler

That night German radio announced what the British press called the “most dramatic news of the war,” the death of Adolf Hitler. With Hitler’s death, German resistance completely crumbled. The 11th Armored reached Lubeck on the Baltic ahead of the Soviets, and the 6th Airborne achieved Wismar to link up with the Red Army.

With Hitler dead, his successor was Admiral Karl Dönitz in Flensburg, Schleswig-Holstein, and his first move was to send a delegation under Admiral Hans-Georg von Friedeburg to Field Marshal Montgomery’s headquarters on the Luneberg Heath to surrender the forces facing the Soviets to Montgomery.

The field marshal would have none of that. After showing the German delegation their positions on his situation map—more accurately than the Germans had previously understood—Monty demanded the surrender of the forces facing him. Friedeburg broke into tears. On May 4, the Germans opposing Montgomery surrendered. The Western Allied invasion of Germany was an official success.

The surrender set off a wave of related ceremonies. Maj. Gen. James Gavin and the 82nd Airborne took the surrender of General Kurt von Tippelskirch’s 21st Army along with 150,000 men on May 2 in a “cold and very proper” ceremony at 82nd headquarters at Ludwigslust.

One critical surrender remained, the Germans in Holland. On April 27, Seyss-Inquart, while refusing to yield, agreed to allow Allied food convoys into the German-occupied areas, and RAF Bomber Command and the U.S. Eighth Air Force, freed of having to bomb enemy targets, began dropping millions of rations close to Rotterdam and The Hague in Operation Manna. The massive food deliveries prevented starvation in the Netherlands by a matter of two or three weeks.

An “Improbable Dream”

Now, with the overall surrender in place, the Germans had to yield in accordance with Montgomery’s directive. General Johannes Blaskowitz, commanding German forces in the Netherlands, drove to a battered hotel in Wageningen to surrender to Lt. Gen. Charles Foulkes, who commanded the 1st Canadian Corps, and Prince Bernhard of the Netherlands. The corps’ war diary recorded, “The terms of surrender were read over by General Foulkes, and Blaskowitz hardly answered a word. Occasionally he would interpose with a demand for more time to carry out the orders given to him, otherwise nothing was said from the German side. They looked like men in a dream, dazed, stupefied and unable to realize that for them their world was utterly finished.”

There was a further surrender at Aurich, where Brigadier Jim Roberts, commanding the Canadian 8th Infantry Brigade, had to assist with the surrender of German forces facing General Guy Simonds’s 2nd Corps. There was no conversation, and General Erich von Straube, nicknamed the “Little Watchmaker,” gave up what was left of his 84th Corps to the dour Simonds.

After the ceremony, Roberts had to drive the Germans back to their headquarters, and for 20 minutes they rode in silence. Then von Straube tried to break the tension, asking Roberts what he did before the war. “Were you a professional soldier?” Straube asked, hoping he had given in to a fellow full-time warrior.

Roberts was stunned and unsettled by being asked about a world at peace, which seemed an “improbable dream.” He only looked at the surface of the question. He said, “No, I wasn’t a professional soldier. Very few Canadians were. In civilian life, I made ice cream.”

Originally Published December 29, 2016. Updated December 14, 2020.

Thanks for a few stories on Canada’s contribution to WW2.We are often linked as “British” which is understandable but it’s always nice to read some Canadian stories or battles.The last line was especially intersting as my grandfather owned a grocery store and his butcher was a veteran of the campaign in Holland.Married a Dutch Bride and brought her here as a matter of fact.The owner of the “gas station” was also a veteran of the Dutch campaign and all i really know is that both of these men were “paratroopers” and jumped in to liberate Holland.I was very young when i knew these two men and both are long since deceased.But the questions i’d have if i knew them now!!!

Thank you for your warm words about my article, Cleetus.

I was determined from the moment I started this article to put the Canadians front and even with the British liberators, as I have studied Canada’s harsh war and contributions to victory.

I relied on the fantastic works of my friend Mark Zuehlke, those of Brig. Denis Whitaker, who both fought in that campaign as a junior officer and became a military historian later, and “The Long Left Flank,” by Jeffery Williams, which provided the fantastic closing quote from Brig. Roberts. It said so much about how the Canadians turned quiet civilians into victorious officers and other ranks.

Your comment about the Canadian veterans bringing home brides from Europe is moving — more than 40,000 British women married Canadian soldiers, too. Wherever the Canadians — and Americans and British, of course — went, they brought home wives. While there were occasions when the marriages didn’t work out, the outcomes for the majority was happy — they enjoyed their husbands and children, loved their new homes and higher standards of living, while never losing touch with home — children of American GIs and Sailors who married Japanese women grew up used to wearing kimonos and eating sushi for one meal and blue jeans and t-shirts for hot dogs for another.

I have written for this magazine for 25 years, so you should look for my other work here on this web page and let me know what you think.