By Blaine Taylor

The career of Admiral Nicholas Horthy spanned not only two world wars, but also stretched across the decades from the age of sail to atomic-powered submarines. He witnessed the fall of Europe’s oldest dynasties during 1917-1919, the rise of dictatorships to replace them, and the advent and then collapse of fascism as well.

His own country, Hungary, twice fell victim to Soviet revolution and foreign occupation, and he lived long enough to witness the aborted Hungarian Revolt of 1956. Although he did not survive to see her free once more, this salty sailor predicted that Hungary would emerge again in his post-World War II memoirs.

He was one of only two of Adolf Hitler’s former Axis partners in Europe to survive World War II. Both Benito Mussolini of Italy and Marshal Ion Antonescu of Romania were executed by the communists, while King Boris of Bulgaria died of a mysterious heart attack in 1943. Croatian strongman Dr. Ante Pavelic, like Admiral Horthy, escaped.

Nicholas Horthy outlived them all as the deposed regent of Hungary, a former Imperial Austro-Hungarian Navy commander in chief who was head of state in a landlocked nation virtually without a fleet. A reluctant politician who had been first a career sailor all his life, Horthy had served as aide-de-camp to the Dual Monarchy’s Kaiser Franz Joseph for the five years preceding the outbreak of World War I in 1914.

In that capacity, he rubbed shoulders with kings, sultans, and the emperor of Germany, and later would hobnob with Victor Emmanuel III of the House of Savoy, Pope Pius XII, and the Führer of the Third Reich, Adolf Hitler. It was Hitler who dominated the last years of Horthy’s 25-year regency, and Horthy thus has come down to history as a mere vassal to Hitler, but he was much more than that.

From Naval Cadet to Elected Dictator

Horthy rose from being an unknown naval cadet at Pola on the Adriatic Sea in the 1880s to command the Austro-Hungarian fleet in 1918. He was appointed to that post by Austria’s last Emperor, Kaiser Karl I, a man whose return to power he would thwart in 1921. Forced to surrender his proud, undefeated vessels to newly formed Yugoslavia on October 31, 1918, Horthy saw his naval career give way to one in a field he had always avoided, politics.

Within just a few months, the victor of the Battle of Otranto would be acclaimed as the national hero of his native land for the liberation of Budapest from the communist takeover led by Bela Kun. And as the elected regent of Hungary, he would reside in the former royal palace in the formidable Burgberg. Offered the crown himself, Admiral Horthy refused it, preferring to rule instead as an elected dictator. He was one of the few admirals in history who came to office at the head of an army rather than a fleet.

Caught between two powerful neighbors, Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia, Horthy’s Hungary threw in her lot with the Nazis against the Bolsheviks when Hitler invaded the Soviet Union in 1941, but was seeking a way out of the conflict as early as the following year, convinced that the Third Reich would lose the war. Reportedly, Horthy was one of the few foreign leaders whom Hitler respected, and why not? By the time Hitler was born, Horthy was already an Imperial Navy officer.

While Hitler was an unknown corporal in the trenches on the Western Front in 1917, the admiral was the naval hero of Austria-Hungary, and when the demobilized future Führer was a struggling politician in Bavaria, Nicholas Horthy was elected regent by a landslide vote of 131 out of 141 ballots cast in the parliament at Budapest.

Moreover, Hitler only traveled to countries he occupied, while mariner Horthy had long since sailed the oceans of the world. Thus, both before and during World War II the crusty sailor stood up to Hitler in a way that few Axis Pact partners dared. In return, the Führer may have murdered the regent’s first son. He did send SS Colonel Otto Skorzeny to kidnap the second son, occupied Hungary with nine German divisions late in 1944, and imprisoned the deposed regent, his former ally, in a Bavarian castle.

It was there that the 78-year-old admiral narrowly escaped execution by SS bullets in the spring of 1945 when the U.S. Army liberated the Horthy family outside Munich. Protected from extradition on Josip Broz Tito’s demand to stand trial in Yugoslavia for alleged war crimes, the regent instead was saved by the American government to testify as a witness in both 1945 and 1948 at the war crimes trials conducted in Nuremberg by the International Military Tribunal.

Over the course of his rich and varied life, Horthy had married the best dancer he ever met, hunted tigers in Borneo, seen the Himalayas, gotten drunk in Spanish ports, and survived a 70-foot fall from the mast of an Austrian training ship. His life was truly an epic.

“Above Life Stands Duty”

It was an unusual saga, beginning with his birth in Hungary in 1868 to a family of landed gentry tracing its lineage back several centuries. Young Horthy’s dream was almost instantly to go to sea as a career sailor, but it almost was not realized because an older brother had died at the Imperial Navy’s Academy at Pola. In 1882, his parents reluctantly granted him permission to seek entrance.

Years later, Horthy recalled that of 612 applicants to the academy only 42 were admitted as officer candidates, and of those only 27 were later commissioned. The future admiral adopted as his own lifelong slogan the motto of the naval academy: “Above Life Stands Duty.”

As a graduated midshipman, young Horthy was assigned to the Winter Squadron flagship Radetzky, a frigate named after a famous Austrian Army field marshal. The ships were still powered by sails, with steam boilers hardly ever stoked, including the armor-clad vessels. Skippers who still felt more comfortable sailing thus preferred going into harbors under sail, rather than employing the newer steam power of a more modern era.

The future regent graduated from sailing vessels to torpedo boats and would later command both armored cruisers and battleships as well. Overall, his many voyages over the course of 36 years would take him to England, France, Spain, Portugal, Turkey, Malta, Gibraltar, Tunisia, Greece, Egypt, Somalia, Thailand, Indonesia, Australia, New Zealand, New Caledonia, Italy, and the Solomon Islands, to name but a few places.

The pragmatic Horthy commanded respect from Hitler and received greater latitude than other

nominal heads of state who served the Nazis.

Horthy joined the torpedo service of the Imperial Navy, preferring it, he said, to the other three possibilities: the desk-bound naval staff, minelaying, and heavy surface units. Staying ever longer on sea exercises, it meant faster and more promotions, Horthy later asserted.

A Swift Rise Through the Ranks

Following his command of both a training ship and the school that prepared young boys as future naval petty officers, Horthy found himself serving as a government translator in Vienna. He translated the naval budget from German into Hungarian for the joint parliamentary review in Budapest, as provided for in the 1867 constitution between Hungary and Austria.

Shortly afterward, he met his future wife, Magda Purgly, at a dance, and they were married on July 21, 1901. The happy union would endure war, revolution, overthrow, arrest, and exile, as well as having their homes looted by Romanians, Hungarians, and Russians.

Horthy’s rise in the Navy was swift. From skippering a torpedo boat, he next commanded a destroyer flotilla, and then the battleship Habsburg, flagship of the fleet’s Mediterranean Squadron, before World War I. One of his colleagues in the Navy was another admiral, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, who insisted on promoting the offensive capabilities of the Imperial Navy, not only its role as a coastal defense force. It was he whose assassination at Sarajevo on June 28, 1914, touched off the Balkan powder keg, which soon spread to a general European conflict.

Aide-de-Camp to Franz Joseph

Horthy was twice stationed at Constantinople in Turkey, where he witnessed the famous Young Turk rising that overthrew the old sultan. When Austria took advantage of the crisis and annexed Bosnia-Herzegovina, the Turks responded by boycotting and seizing imported Austrian commercial goods as well as refusing to allow cargo to be unloaded. Since Turkey was Austria’s main customer for exports, Horthy decided to act to break the impasse.

When the nervous Austrian ambassador asked what Horthy would do if fired upon, he coolly replied that he would return the fire, even if it meant war. All went well, however, Horthy recalled in the 1950s, as the Kurds declined to fight. The sailor had learned that bold, decisive action provided results, a lesson he remembered during World War I.

This action as well as his reports to Vienna on the Young Turks brought him to the attention of the aged Emperor Franz Joseph, and in 1909 Horthy was named the monarch’s naval aide-de-camp, a high point in his celebrated career.

Decades later, Admiral Horthy still recalled with awe his first meeting with the Austrian Kaiser. As a boy, Horthy heard the king-emperor mentioned only as a near godlike figure, but now meeting him in person in an Austrian Army general’s uniform, he witnessed a man of grace and dignity stepping forward quietly to meet his new aide.

In retrospect, Horthy never forgot the regal impression that Kaiser Franz Joseph made on him, and long afterward he recalled it as the greatest moment of his long life.

Early Successes For the Austro-Hungarian Navy

When the world war broke, Horthy had been promoted captain of a ship of the line and traveled to Vienna to report to naval headquarters, where the next day he was received by the Archduke Charles, the new heir apparent to the throne of Austria-Hungary. Asked if it would be war or peace, Horthy accurately predicted the outbreak of World War I, and the future kaiser wrongly contradicted him.

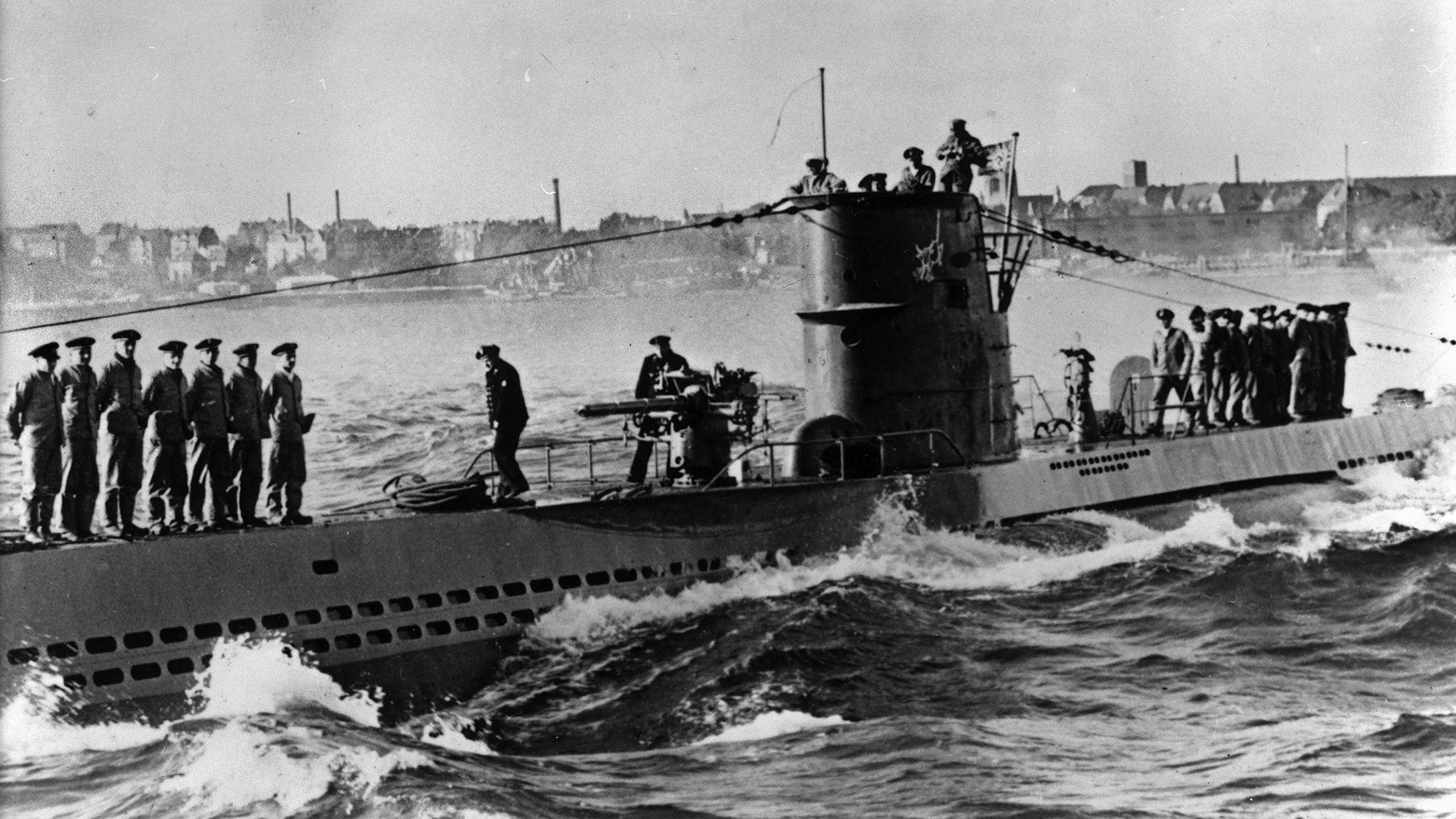

At the start of the war, Horthy was named once more to command the aging, slow, and underarmed Habsburg, but soon was given the just completed armored cruiser Novara. In her, Horthy broke through the Allied naval blockade of the Adriatic Sea to help the submarine U-8 escape through the Straits of Otranto, thereby forcing the British Royal Navy to redistribute its surface units.

When Italy entered the war in 1915 on the side of the Allies, within hours the entire Imperial Navy was steaming to attack the Italian east coast from Venice to Brindisi. Horthy’s job was to delay the Italian advance by interdicting the Italian railway system along the Adriatic, thereby giving the Austro-Hungarian forces time to move to the border where few battalions were posted, opening the road to Vienna.

The Italians, afraid of a landing at Ancona and an assault on Rome in their armies’ rear, halted their advance. Horthy had achieved his goal.

Horthy’s First Combat in World War I

Commanding the Novara and the destroyer Scharfschutze, Captain Horthy put out of action a coastal signal station and its protecting shore battery, which placed a few hits on one of his ships during his first combat of the Great War. Once, he almost succeeded in intercepting King Peter of Serbia on an Allied destroyer, only to discover that the ruler abandoned the projected voyage because of seasickness.

Horthy’s next venture, through one of his officer’s decoding skills, was more successful, enabling his ships to sink 23 steamers and sailing ships on a night raid on the port of San Giovanni di Medua, an Albanian harbor occupied by the Serbs.

The port hosted a battery of 10 guns. Hugging the rugged Albanian coast until the breakwater was taken, Horthy saw a single-story dwelling housing the sleeping gun crews. A single salvo blew it up, thus also putting its battery out of action. Overjoyed, Horthy and his men beheld a harbor full of ships that had arrived the night before by sheer happenstance.

Had they come a day earlier, they would have found an empty harbor; a day afterward, and most of the cargo would have already been unloaded. Giving the crews time to leave their vessels, he opened fire on them.

The Battle of Oranto

The Central Powers began unrestricted submarine warfare against the Allies on February 1, 1917, and Horthy found that the Straits of Otranto must be forced if the submarines were to be successful against Allied merchant vessels. His recommendation for such a battle was accepted by the higher command, and so the stage was set for the Battle of Otranto of May 15, 1917, to allow 32 German and 14 Austrian submarines to escape.

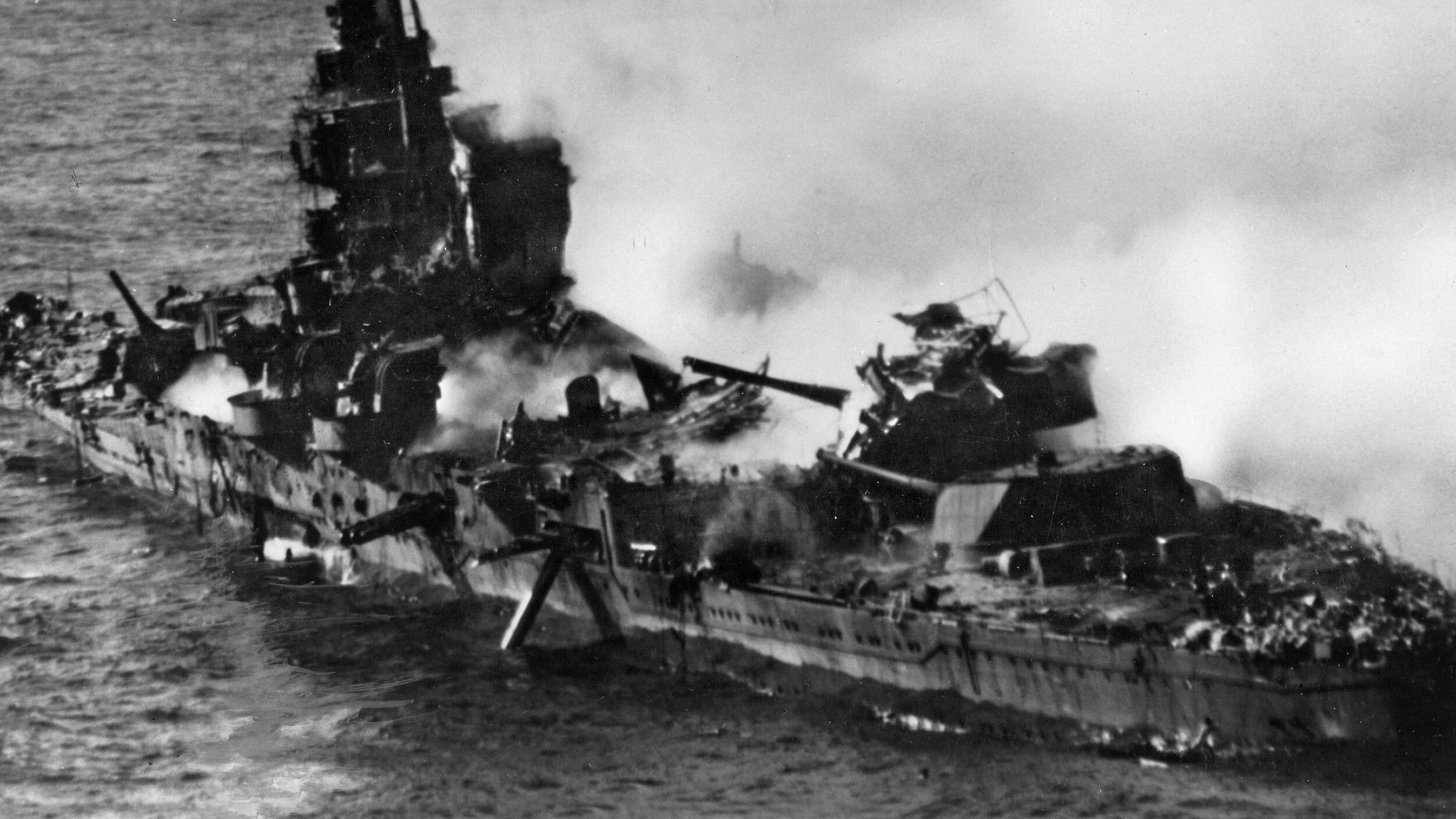

Horthy’s flotilla faced a combined British-Italian-French force. He was wounded by a shell that exploded nearby at 10:10 am, with five shell splinters embedding themselves in one of his legs. In addition, a piece of shrapnel weighing a couple of pounds whisked Horthy’s cap off his head. Later a piece of metal with the singed shreds of his naval officer’s cap still adhering to it was handed to him. Remarkably, he did not suffer a single burn. However, he did feel as if he had been knocked over by a blow to the head with an axe.

Horthy continued to command the action, however, from a stretcher placed on the Novara’s bridge, but a direct hit put her out of action less than a half hour later. The battle appeared to be lost when Horthy asked a junior officer to examine the situation with a pair of binoculars. The startled officer proclaimed that it seemed to him that the enemy ships were turning tail and retreating. They had.

What had happened to give Horthy such an unexpected victory at seemingly his moment of bitter defeat? Aboard the leading British cruiser, an Italian admiral thought better of engaging the Austro-Hungarian battle cruiser St. Georg, as it was backed up by the coastal patrol vessel Budapest, thus opting to allow Novara to escape.

Horthy’s three cruisers had faced one Italian and two British cruisers along with 11 Italian and three French destroyers. He had destroyed 23 net-trailing antisubmarine drifters, two transports, two destroyers, and one aircraft. He had not lost a single vessel and had opened the straits.

Surrendering the Fleet

The Battle of Otranto made Horthy a national hero in Austria, leading the new 29-year-old Kaiser Karl to name him both a rear admiral and commander in chief of the Fleet over the heads of many older, more senior officers in the final year of the war, with both defeat and mutiny looming. Discovering one plot by two sailors to murder the officers while a ship was at sea, Horthy had the mutineers hanged in sight of delegations of others from around the fleet, but knew that this would not prevent a general revolt.

His answer was to take the idle ships and crews to sea for renewed action, but by late 1918 even this would not stave off an inevitable defeat brought about by the reverses on land. On October 26, Emperor Karl informed his ally Kaiser Wilhelm that the dual monarchy was dropping out of the war and would seek an armistice with the Allies.

Kaiser Karl was convinced by Croat generals to surrender his proud fleet to the Yugoslavians to keep it from falling to the hated Italians. Thus, it was Horthy’s sad duty to haul down both his own pennant as admiral and also the ensign of the doomed empire. On October 31, 1918, his naval career abruptly came to an end.

The next day, his flagship, the battleship Viribus Unitis, was sunk by a mine placed on her by two Italian frogmen. His successor as naval commander went down with her.

Horthy’s Counterrevolution

Horthy and his wife lost their home at Pola and all the belongings they had accumulated over 17 years of marriage. This was the house he had built in which all their children had been born. They departed with his officers on a special train, his career in ruins, it seemed. What could he look forward to in Hungary, a country in the throes of revolution?

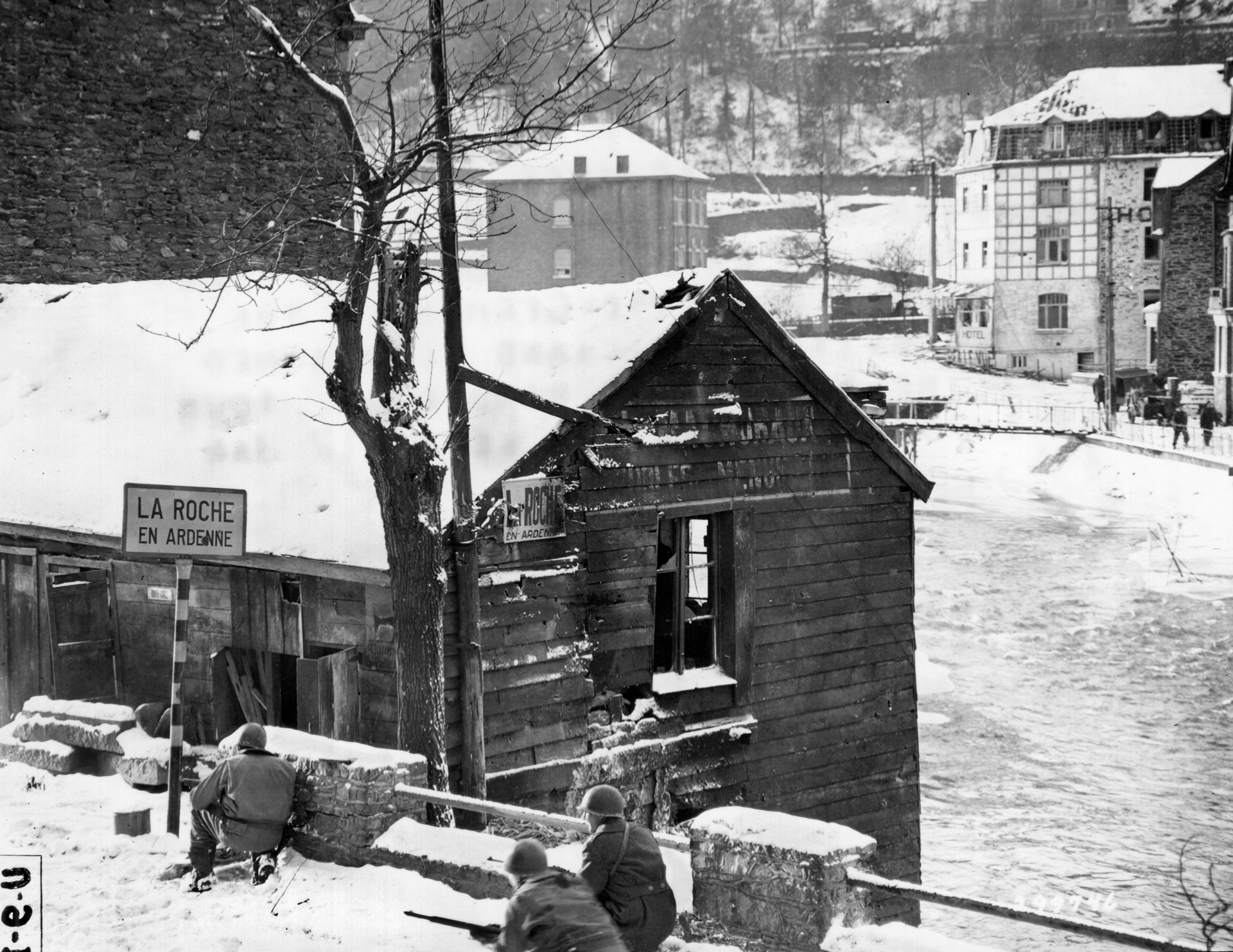

Hungary’s neighbors, the Czechs, Serbs, and Romanians, had each taken chunks of the country, all sanctioned by the victorious Western Allies. At home, on March 21, 1919, the domestic leftist factions united to form a Soviet-style Republic of Hungary. The Romanians advanced, unrestrained by France and Britain, further into prostrate Hungary. Demands for a counterrevolution set in, and Horthy was asked to form a national army of liberation.

He did so, and on November 16, 1919, Horthy entered Budapest on a white horse at the head of his troops, launching a white terror that eradicated Hungarian communism for the next generation. Since the Austro-Hungarian monarchy had been dissolved and Hungary still considered herself a kingdom without a king, the parliament voted that a regency should be established until a monarch would once more sit on the throne at Budapest.

Rising as Regent

Because the Allies would not allow the restoration of the Habsburg dynasty in any form, two former archdukes were immediately disqualified for the post of regent.

Horthy, however, as both a non-Habsburg and a native Magyar who was also a national hero, filled the bill perfectly. Thus, on March 1, 1920, he was elected the first regent of Hungary since 1452, a post that he asserted he neither sought nor wanted.

This was called into question, though, the following year when the deposed Kaiser Karl twice attempted a comeback. On the first occasion, the ex-emperor’s former naval commander held a secret meeting at the palace, and on the second wrote him a personal letter, begging him to leave the country to spare it both civil war and foreign invasion. On both occasions, the former emperor heeded Horthy’s entreaties. Karl died the following year of pneumonia at age 34 in exile on the Portuguese island of Madeira.

Horthy, too, would die in exile, at age 90 in 1957 at Estoril in Portugal, but not before recovering Hungary’s lands lost at the end of World War I from the hands of Hitler.

Alliance With Hitler

His first meeting with the German Führer was in 1936 at Berchtesgaden in Bavaria.

The sailor’s first impression was that Hitler was a moderate and wise statesman, and he later admitted that he was not the only leader so mistaken.

By the time of Horthy’s triumphal state visit to the Third Reich during August 24-26, 1938, the regent found the Führer a changed man, visibly and audibly behaving as the master of Europe. Hitler briefly sketched for Horthy his design to absorb Czechoslovakia, his aim being to smash the Czechs.

Three years later, Horthy was still Hitler’s ally, however, as he visited Hitler’s East Prussian headquarters, from which the invasion of the Soviet Union was being conducted. Hungarian troops fought at Stalingrad, but by then Horthy realized the war was lost and was seeking a way out.

Two spring meetings with Hitler at Castle Klessheim in Austria, in both 1943 and 1944, proved acrimonious. At the second, the Führer demanded the establishment of a pro-German protectorate in Hungary, and an angry Horthy stormed out of the conference room, an act that Hitler had never before encountered. He ran after his irate guest and persuaded him to stay on as regent.

The Rise and Fall of Communism in Hungary

By October 1944, Horthy had decided on an armistice with Joseph Stalin of the Soviet Union, as well as with the West, to prevent a Soviet invasion of Hungary. It was not to be, though, as the German SS kidnapped his son and placed the regent under arrest, shipping him and his family to exile at Castle Hirschberg outside Munich until the end of the war. Hitler ordered Horthy’s execution, but the coming of the U.S. Army caused his Gestapo and SS jailers to flee in civilian clothes on May 1, 1945.

Hungary was, indeed, invaded by the Red Army. Budapest was captured after a devastating two-month siege on February 13, 1945, and her armies surrendered that April. As for Regent Admiral Horthy, he went to his death believing that this second communist yoke would eventually be thrown off. In 1989, he was proven correct as democracy was established 32 years after his death.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments