By Dana Lombardy

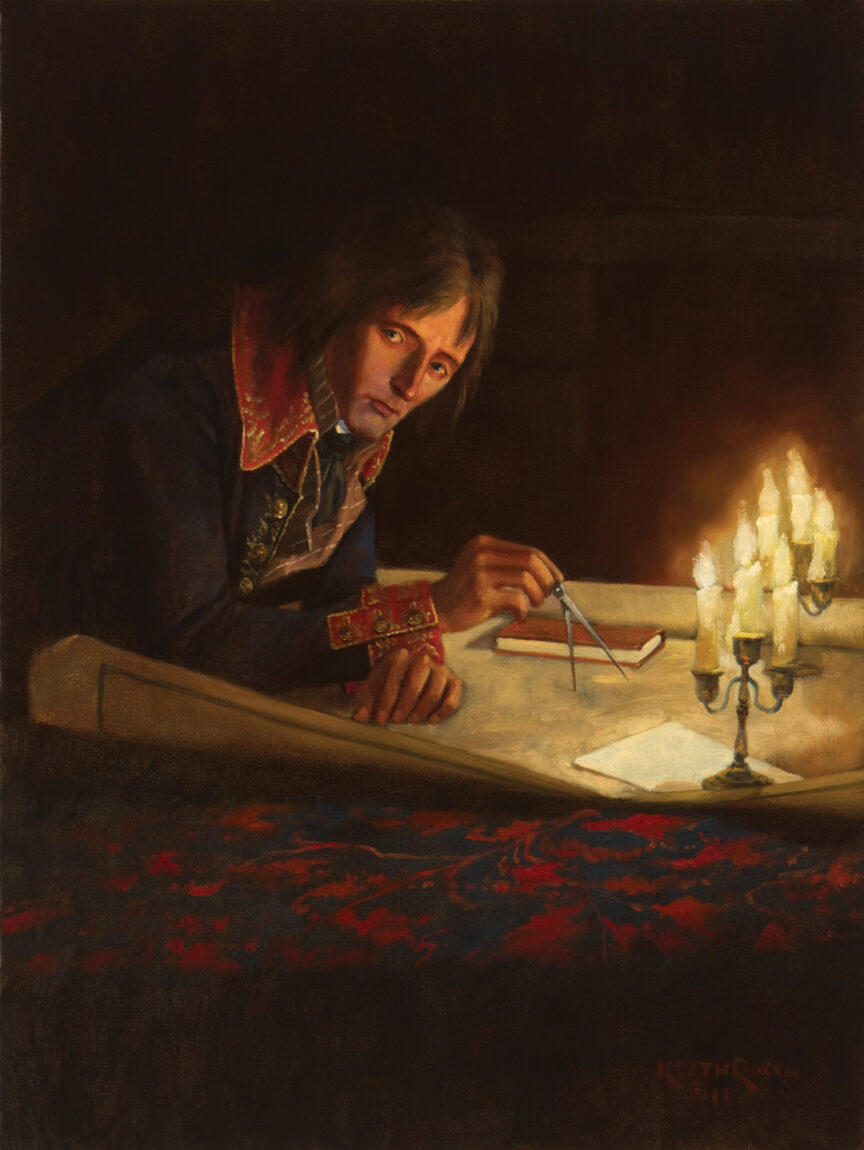

Barthélemy Schérer, commander of the French Army, gazed at the new military orders from Paris in disbelief. The grandoise strategy, detailing an advance on three fronts with the armies uniting in Tyrol for a concentrated thrust at Vienna, were far beyond the capabilities of the starving southern army he commanded along the French Riveria against the combined forces of Austria and Sardinia. Disgusted at the situation before him, he asked to be relieved. He also suggested that the member of the Topgraphical Bureau who drafted the strategy, the 26-year-old upstart Corsican, General Napoleon Bonaparte, be sent to carry them out. And that is exactly what happened. On February 23, 1796, Schérer was relieved of command and replaced with Bonaparte.

In 1792, Revolutionary France went to war with Austria and Prussia. Following the execution of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette in January 1793, Great Britain, Spain, the Dutch Republic, and several minor Italian states joined what became known as the First Coalition. Its mission was to restore the French monarchy and destroy the French Republic before its ideas of liberty, equality, brotherhood among men, and violence spread to other nations.

Napoleon had missed the greatest fame and glory achieved by revolutionary France in 1794. French victories that year wrecked the First Coalition. Holland became the Batavian Republic in January of 1795 and an ally of France. Prussia made peace in April 1795, and Spain did likewise in July. By the summer 1795, Britain, Austria, and Sardinia were the only major powers still at war with France.

The Directory’s strategy for 1796 did not have an overall plan other than to invade enemy territory. The unpaid, underfed, and nearly mutinous soldiers of France were susceptible to a military-led revolt. A successful war of aggression could enable the revolutionary armies to feed, clothe, and pay themselves off of the enemy.

Napoleon’s Army of Italy

On paper, Bonaparte’s Army of Italy had 116,000 men. In reality, effective strength was about 61,000, and more than two-thirds of these troops were spread out nearly 200 miles along the Mediterranean coast from the French city of Marseilles to the small town of Voltri, nine miles from the important port of Genoa, Italy.

The French forces were dispersed to feed themselves off the local countryside and to protect their vulnerable coastline and coastal roads against British and Sardinian naval raids. As soon as he arrived, Napoleon moved the army’s headquarters forward 42 miles from Nice to Albenga and went on rounds of personal inspections, which allowed Bonaparte to assess the capabilities of his army.

On March 28, he wrote to the Directory that the “administrative situation of the army is bad, but no longer desperate…. From now on the army will eat good bread and will have meat, and it has already had considerable advances on its back pay…. I shall march in a short while.”

The Army of Italy had 11 divisions. Four of these were for coastal defense administratively controlled from Nice. Under Bonaparte’s direct control at the front were seven divisions: André Masséna’s advance guard that included Amédée Laharpe’s and Jean-Baptiste Meynier’s divisions, Charles Augereau’s division, Jean Sérurier’s division, Henry-Christian-Michel Stengel’s cavalry division, and two small divisions under Pierre-Dominique Garnier and François Macquard.

Stengel’s cavalry protected the army’s rear along the coast, while Garnier and Macquard held defensive positions on the far left that linked up with the Army of the Alps. That left four divisions with 37,600 men for Napoleon’s offensive, a force about 70 percent the size of the enemy they faced.

Beaulieu and Colli

Opposing the Army of Italy were two separate allied armies. After De Vins resigned due to illness in 1794, an experienced 56-year-old Austrian general, Baron Michelangelo Alessandro Colli-Marchi, took command of the 25,000-man Sardinian Army in the Ligurian Alps of northern Italy. Colli’s troops were spread out guarding mountain passes, including the key town of Ceva. If the French broke through the mountains in this area, they could march on the Sardinian capital of Turin around 50 miles away.

An Austrian army, supported by Neapolitan cavalry, deployed 30,000 troops under the command of 70-year-old Jean-Pierre de Beaulieu, a veteran of the Seven Years’ War and battles against revolutionary France from 1792. Beaulieu took command in March 1796, the same month that Bonaparte arrived.

Beaulieu and Colli were friends who in theory were equal in command responsibility. In reality, Beaulieu’s views prevailed. Both men noted Napoleon’s arrival in March and anticipated a French offensive. Colli’s chief of staff wrote: “General Bonaparte is not known for any striking feat, but he is understood to be a profound theorist and a man of talent.” The Austrian commanders also had good intelligence on the condition of the Army of Italy and thought it incapable of a sustained attack in the near future.

Colli’s force of 25,000 was spread over 55 miles of mountainous terrain, watching Garnier’s and Macquard’s divisions and the Army of the Alps in the west and guarding the route to Turin by occupying numerous passes through the Ligurian Alps.

Beaulieu’s army of 30,000 was spread out even more, from its supply depots and line of communication from Milan through Alessandria to a few miles outside the seaport of Genoa, also maintaining contact with Colli near the key mountain pass at Dego. Beaulieu was eager to occupy Genoa to establish direct contact with the British fleet. It would take time to concentrate his widely dispersed troops for this attack, but he felt he had time to conduct a limited operation against an isolated French unit at Voltri near Genoa.

Austrian Advance on Voltri

Beaulieu was convinced that Masséna would be forced to march to the aid of the French troops in Voltri. He hoped that such a move would seriously weaken the French position in Savona and that an Austrian column would be able to capture that coastal town behind Masséna’s anticipated move and trap his command.

Occupying Voltri was supposed to pressure Genoa into providing the French with money and provisions. However, it achieved little in obtaining supplies and only left the French Army badly extended and vulnerable to attack. Before Napoleon could start his offensive, 3,200 Austrians under Baron Carl Philipp Sebottendorf, supported by 4,000 more under Baron Filippo Pittoni, hit 5,000 French under Jean-Baptiste Cervoni at Voltri on April 10. After a few hundred casualties, the French retreated the next morning.

Bonaparte was described as momentarily furious when he learned that French troops had been pushed out of Voltri. On the other hand, Philippe-Paul de Ségur, an aide to Napoleon, wrote in his memoirs that Bonaparte received news of the Austrian attack calmly and said he knew how to make them regret it.

Regardless of Napoleon’s emotional state, the Austrian attack at Voltri was an opportunity for the French. Nearly 25 percent of Beaulieu’s 30,000 troops were engaged at Voltri and therefore too far away to quickly reinforce the Austrians under Count Eugène-Guillaume-Alexis Mercy d’Argenteau guarding the passes around Dego.

12 Hours of Marching and Fighting

Argenteau was supposed to strike Savona when Masséna left the area to rescue Voltri. Instead, before the battle Napoleon ordered a fighting retreat from Voltri to Savona if required. This proved unnecessary as the French troops were not pursued by Beaulieu’s attacking force. After Beaulieu’s success at Voltri, he started moving his troops to reinforce Argenteau via Acqui. It would prove to be too little, too late.

Beaulieu’s plan to trap Masséna’s force between Savona and Voltri came unraveled. There was no pursuit after the Austrian victory at Voltri, so the encirclement was now totally left up to Argenteau.

Argenteau’s 9,000 troops were spread out 20 miles between Dego and Acqui (and 6,000 assembling another 20 miles away around Alessandria), but he attempted to follow Beaulieu’s orders. Before dawn on April 11, he marched a column of 3,700 men through Montenotte toward Savona. The Habsburg Hungarian and Croat troops made contact with the French just before the latter’s defensive complex of redoubts called Monte Negino.

Argenteau’s soldiers attacked a key French redoubt three times, exposing themselves to fire as they moved up single file along a narrow crest. The French, under Antoine-Guillaume Rampon, were outnumbered but held on stubbornly. An Austrian report written after the battle noted that most of their officers were killed or wounded leading the attacks on the French redoubts. Although casualties were actually light (fewer than 100 for the French, slightly more for the Hungarians and Croats), Argenteau’s men were exhausted from nearly 12 hours of marching and fighting over difficult mountainous terrain.

Argenteau pulled his column back as darkness fell and arrayed his men in several lines on Monte Pra where they slept with their weapons. The Austrians were unaware that on that same night of April 12, nearly 26,000 French soldiers in Laharpe’s, Meynier’s, and Augereau’s divisions were marching toward Dego as Bonaparte’s offensive began.

Napoleon’s 1796 Offensive: Splitting the Two Armies

Napoleon’s grand offensive plan was to attack between the two enemy armies, splitting them apart. He could then concentrate against Colli’s Sardinians and, if all went well, decisively defeat them before Beaulieu could join Colli to prevent such a disaster.

A lesser commander might have delayed or even canceled a planned offensive to deal with the two Austrian attacks. Instead, while the sound of distant gunfire could be heard, Napoleon conferred with his generals in Savona to make final arrangements for the movement of three divisions scheduled for that night. This conference occurred after receiving reports that confirmed the Austrians were not pushing on after their victory at Voltri and had been stopped at Monte Negino.

Although Bonaparte left no detailed written plan for his 1796 offensive, it clearly followed the strategy he outlined in July 1795 and in January 1796 when he was working in the Topographical Bureau. It borrowed ideas from Bourcet’s 1744 invasion plan of Piedmont and included months of personal inspection of the operational area by the young general when he served in the Army of Italy.

When Laharpe’s division hit Argenteau’s Hungarians and Croats on the morning of April 12, they appeared out of the morning fog “ like a cresting wave.” The Habsburg commander tried to stand, but he was outnumbered to his front and then another column of Masséna’s men appeared in his rear. The Austrian forces fled rather than be surrounded. It was not much of a battle, but Montenotte was an essential first step in separating Colli’s and Beaulieu’s armies.

Unfortunately for the French, Augereau’s division, with a brigade from Meynier’s division in the lead, was behind schedule. The night march along a narrow 15-mile trail over a high pass failed to catch up with Masséna by nightfall on April 12.

The stage was set for two days of confused combat and missed opportunities that could have wrecked Napoleon’s well-coordinated and initially confident orders.

The fighting on April 12 had seen the French victorious, and Bonaparte issued an order of the day that exaggerated enemy losses and had other inaccuracies—but was probably good for morale.

Holding the Castle of Cosseria

Argenteau sent a report to Beaulieu about his retreat and losing nearly 700 men, noting that Dego was “in the greatest danger.” Argenteau saw the French threat in separating the two armies by taking Dego, but Beaulieu could not reach Argenteau with reinforcements quickly. There were only four allied battalions in Dego (the three French divisions approaching counted more than 30), but Argenteau felt his troops were too exhausted and disorganized to do any more than cover Acqui. Rather than march to aid Dego, he awaited orders and more troops.

Argenteau appealed to Colli for help, but despite learning about the French offensive on the afternoon of April 12, the commander of the Sardinian Army reacted without urgency. Into the area commanded by Marchese Giovanni Provera, Colli sent a combined grenadier battalion to occupy the heights at Cosseria and personally led four more battalions of these elite troops to Monte Zemlo to await the next French effort. These positions blocked the route into Piedmont but did little to support the Austrian and Sardinian troops in Dego.

Napoleon’s orders for April 13 had high expectations: Masséna to push beyond Dego, Laharpe to advance to Cairo, and Augereau to capture Millesimo and the positions that approached Ceva. Sérurier’s division, until now held in the Tanaro River Valley area, was to start its move forward so it could add its weight to the eventual attack on Ceva.

There was a serious logistical reason for the junction with Sérurier. The furthest advanced French troops were already suffering from food shortages and needed to draw upon the supply magazine at Bardinetto, but that road was blocked by the Sardinians at Millesimo. One of Augereau’s brigades under Jean-Baptiste Rusca pushed forward to open that road.

Mistakes by Napoleon’s subordinates and hard fighting by his enemies would nearly derail his offensive campaign after an initially successful first day.

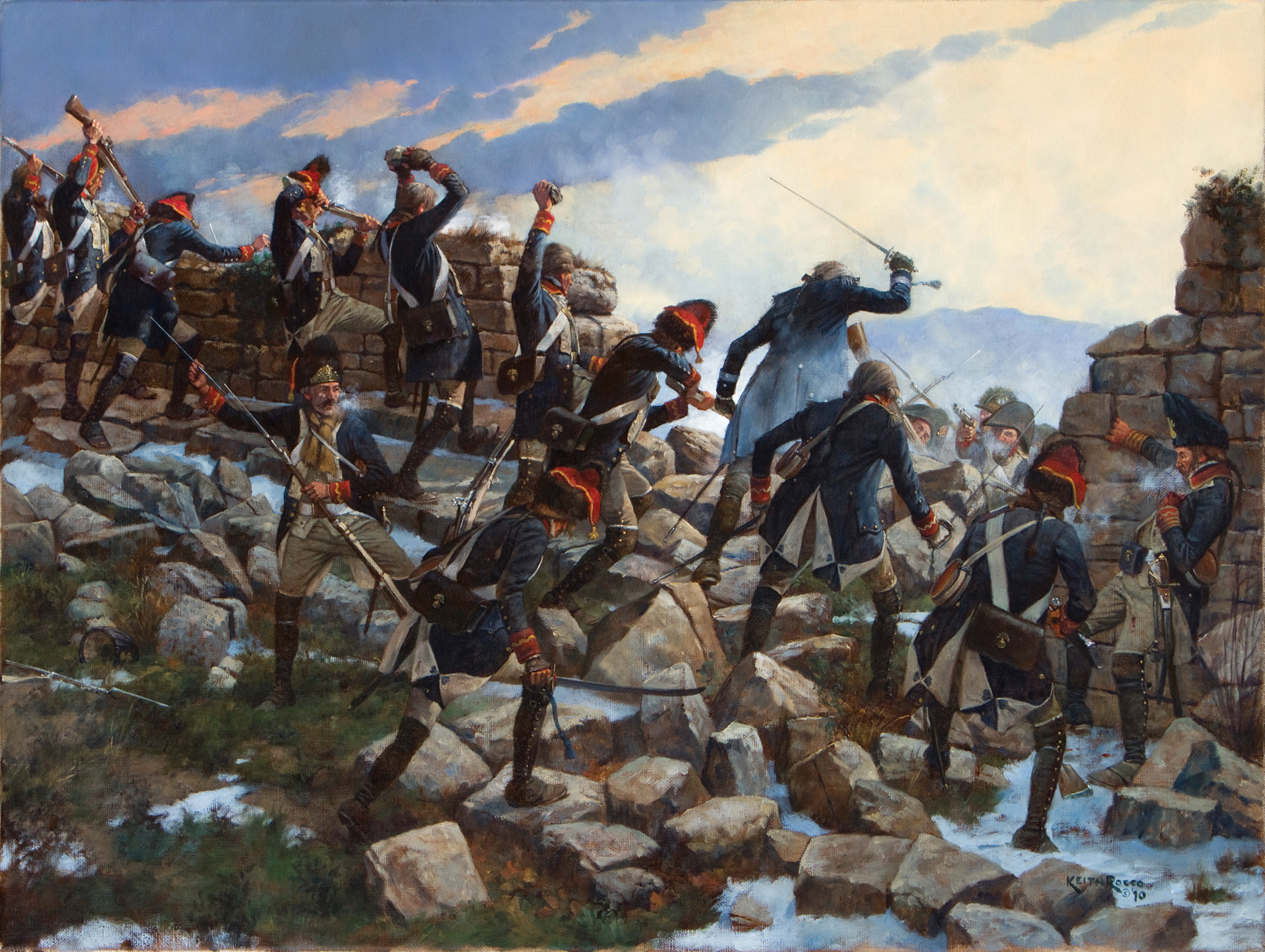

The Sardinian grenadiers reached the castle of Cosseria near Millesimo on April 13 just before Augereau’s division encircled it. After calling for its surrender and being rebuffed, the French made three separate attacks. The final assault began around 4:00 pm and nearly succeeded. The Sardinians, low on ammunition, resorted to throwing rocks at the attackers. Stunned by the fierce defense and loss of several key officers, the French fell back.

The French lost between 600 and 1,000 men in the attacks against Cosseria. A local man who provided lodging for Augereau later wrote that he found the general holding his hands on his forehead, repeating the words: “This blessed castle will force us to turn back to the Riviera.” Colli’s single battalion of Sardinian grenadiers had helped Provera’s 4,000 men stop a division of 8,500 French.

Overwhelming Dego

Masséna, waiting for Laharpe’s troops, decided not to attack Dego on April 13, believing (incorrectly) that it was strongly defended. If Colli and Beaulieu acted quickly, the two Austrian commanders might recover from their perilous situation.

Bonaparte would not give them that chance. Noting that the Sardinians at Cosseria were almost out of ammunition, he thought they would surrender the next day, which they did. He ordered big fires to be lit that night approaching Millesimo from the Bormida valley to make Colli think that Sérurier’s division was closer than it was. Napoleon also rode to Masséna to urge the attack on Dego for April 14.

Masséna’s reconnaissance of Dego on April 13 revealed its defensive weaknesses. Now with Laharpe’s men available, the French employed the tactic that had worked at Montenotte on the morning of April 12: a frontal assault to distract the enemy accompanied by turning movements. Pressured from all sides, the allied defense in Dego crumbled just as Argenteau began arriving with reinforcements.

The victorious French overcame Dego by sheer weight of numbers (Masséna’s 9,500 to 3,000 Austrians under Baron Mathias Rukavina or Roccavina) and then collided with the relief column, throwing it into disorder. A brief pursuit ensued until darkness, including French cavalry that harassed Argenteau’s withdrawal. The French captured at least four colors and from 1,500 to more than 4,000 prisoners, depending upon the report.

The Austrian Counterattack

Convinced that Beaulieu’s forces were not in a position to cause him any more problems, Bonaparte met with his generals at Cairo at 10 pm on April 14. He ordered Laharpe’s division back to Cairo to prepare to join Augereau and Sérurier against Colli.

Discipline broke down among the victorious French at Dego, and they became as disorganized as the retreating Austrians. According to one of the French brigade commanders, “The lack of regularity in the food supply produced many marauders.” There were also numerous incidents of looting and wanton destruction.

The French disintegration meant that there was a lack of military vigilance with few or poorly manned outposts. The Austrians might have been struggling with the new pace of operations dictated by Bonaparte, but they did not lack courage or determination. And they would hit back with a vengeance on April 15 at Dego.

Baron Josef Philipp Vukassovich, one of Argenteau’s better generals, recognized the opportunity and quickly led five battalions of about 3,000 men back toward Dego. A captured French officer told Vukassovich that there were 20,000 enemy troops in the area, but Vukassovich decided to press on.

Like Laharpe at Montenotte, the Austrians appeared out of the morning fog, and the surprised French attempted to form a defense. Several French officers were cut down, which precipitated a retreat. Hundreds of French soldiers were captured as well as cannon that were now put back into service by Vukassovich’s grenadiers acting as artillerymen. Except for the castle in Dego, the Austrians again held the town.

When the seriousness of the situation became apparent to Napoleon, he ordered Laharpe to countermarch his division to Dego. Masséna arrived about four hours after the Austrian attack—his absence for so long a few writers attributed to a woman, or looting. Whether Masséna was derelict in his duties that morning or simply elsewhere on reconnaissance or inspection, when he arrived he quickly proceeded to gather 8,000 men to retake Dego.

Concerned about being enveloped in Dego and with no sign of help from Beaulieu, Vukassovich began withdrawing—constantly harassed by the cautiously pursuing French. His gallant attack made Bonaparte more careful for the next few days, but by the end of April 15 Vukassovich returned to the area of Acqui with only a few of the troops he had led into Dego that morning. By not supporting Vukassovich, Beaulieu missed his best opportunity to thwart Napoleon’s offensive.

Taking Ceva

Four days into his first offensive, Bonaparte had successfully wedged his four divisions between the two allied armies. Operations had not developed perfectly, however, and it required Napoleon’s repeated attention at various points along the front to maintain the initiative he seized on April 12. Compared to Colli and Beaulieu attempting to direct their forces from the rear, Napoleon’s style of personal, relentless leadership was a paradigm shift in warfare.

After regrouping and obtaining sustenance for his troops from local authorities and reconnaissance to make sure that no substantial Austrian forces were within striking distance on April 16, Napoleon prepared for the attack at Ceva (although he left Laharpe’s division in the Dego-Montenotte area as a precaution).

Colli had retreated from Monte Zemlo to the fortified town of Ceva and the network of defenses around it. Bonaparte knew about the formidable positions from the memoirs of de Maillebois, but now he could actually see them.

Colli did not expect the French to attack such a strong position, and, suspecting that Bonaparte would attempt a maneuver against his vulnerable right, he marched away with eight battalions the night of April 15. That still left around 13,000 Sardinians to defend Ceva, and they defeated all attempts on April 16 by Augereau’s 7,500 troops to probe (French version) or attack (Sardinian opinion) their redoubts.

Despite the successful defense at Ceva on April 16 and the heroic stand at Cosseria on April 13, morale among the senior Sardinian officers was low. Now on his way back after learning of the French attack at Ceva, Colli received a report from his commanders that they thought it wise to retire. The hostess of the house where Colli stayed that night wrote in her journal: “Fear and indecision were the result of the council of war.” Colli wrote the order to abandon Ceva.

Augereau occupied the abandoned entrenchments at Ceva the next day, and Bonaparte ordered an immediate pursuit, ignoring the small garrison left behind in the town’s citadel. There would be no costly French assaults as had occurred at Cosseria, and no siege. The French marched off, leaving the few Sardinian troops in their rear. As there were virtually no supplies reaching the French troops, there was nothing for the Sardinians to intercept or cut off.

Retreat From San Michele

Colli’s next strong defensive line was at San Michele (also called La Bicocca), where he positioned 8,000 men and 15 guns. An assault on April 19 by 11,500 troops under Augereau and Sérurier was stalled until a group of skirmishers following retreating Sardinian pickets was able to cross at an unguarded aqueduct and a French brigade got across the river to cause panic among the defenders.

As at Dego, the victors immediately began to pillage. This time it was Sérurier’s division that was punished for its lack of discipline, being thrown out of San Michele by a counterattack organized by Colli. Lack of food was the bane of the French Army of Italy, and halting the offensive ran the risk of seeing it disintegrate into a rabble. The people of the mountainous region could barely support themselves, let alone nearly 40,000 hungry French soldiers and their horses.

Napoleon held a meeting with his generals at Ceva to prepare to retake San Michele. But the French spent April 20 mostly resting the troops, finding food, and restoring discipline and order.

Despite his victory at San Michele, Colli emptied supply magazines and destroyed bridges preparing for further retreat. Until Beaulieu’s army could reach him, Colli wanted to preserve his army. During the night of April 20-21, the Sardinians pulled back toward the large magazines at Mondovì.

Negotiations With Napoleon

Bonaparte arrived that night to scout San Michele for the next day’s action. He found a ford that enabled his troops to cross the river despite the destroyed bridge and discovered that the Piedmontese had gone, leaving their campfires burning. Napoleon ordered an immediate pursuit, catching Colli’s rear guard late the next morning. Very quickly, Colli’s army was retreating in confusion.

Napoleon, accompanied by his friend Saliceti, made a triumphal entry into Mondovì on April 21. That night, King Victor Amadeus III met with his ministers in Turin and sent envoys to meet the French government representative in Genoa. A letter was also sent to Colli asking him to open negotiations with Bonaparte for an armistice.

Napoleon received Colli’s letter on April 23, but he continued his movements toward Turin and replied that evening that only the Directory could negotiate peace. However, if two of the three fortresses of Cuneo, Alessandria, and Tortona were turned over to the French, he would suspend hostilities. To make sure that Beaulieu’s forces would not link up with Colli’s demoralized army, Augereau seized Alba, and Masséna occupied Cherasco.

With help from Beaulieu unlikely and his demoralized and weakened army just miles from Turin, King Amadeus accepted Bonaparte’s terms on April 26. It was just 15 days since the French offensive began on April 12.

Armistice With Sardinia and Austria

Bonaparte had accomplished in two weeks what none of the commanders fighting in this area of Italy had been able to achieve in the 1740s or from 1792-1795. To some historians, it was the weakness and betrayal of the Sardinian king that gave Napoleon his victory. However, French soldiers were often beaten by their hard-fighting adversaries in the 1796 campaign, and the Austrian commanders were dedicated professionals who did not quit easily.

The primary reason for the end of the Italian stalemate in 1796 was Napoleon Bonaparte. He simply outthought, outplanned, outreacted, and outgeneraled his opponents.

Napoleon signed an armistice with Sardinia on April 28, which violated the Directory’s orders that he take no diplomatic action. However, when his brother Joseph reached Paris with letters and reports announcing the army’s success along with 21 captured Austrian and Sardinian colors and much loot, the Directory ignored Bonaparte’s insubordination and showed gratitude for the victory France badly needed in the spring 1796.

In keeping with his new style of military operations, Napoleon did not rest on his laurels. He provisioned his army at the expense of Sardinia, reorganized it into a more effective force, received reinforcements from the nearby French Army of the Alps, and by May 5, only a week after signing the armistice with Sardinia, was already chasing Beaulieu across northern Italy.

After nearly another year of fighting, Napoleon forced the Austrians to sign an armistice in April 1797.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments